Final report for FNC15-1023

Project Information

Our research was conducted on a six acre plot in the Missouri River bottomlands outside of Jefferson City, MO. It was a rich, sandy field adjacent to conventional corn and soybean production. In 2014, parts of the site were in potato and cover crops (3 acres). The remainder had been planted in sweet corn (3 acres). Prior to 2014, the entire field was in commodity crop production. In 2015, we planted an acre each of potatoes, sweet potatoes, butternut squash, black beans and watermelon using low-input production systems. We define "low-input" as a system that limits the use of costly external inputs such as conventional fertilizers, herbicides and fossil fuels. In place of these, our production system used cover crops, crop rotation, integrated pest control measures, and manual planting, cultivation and harvest.

The Mid-MO Growers Group formed as a partnership with a vision of growing vegetables collaboratively in central Missouri. With less than one percent of the state's agricultural land currently used for vegetable production (USDA Census of Agriculture 2012), we see potential to diversify production systems to incorporate more direct-to-market vegetable crops. In theory, this would support higher profits per acre, more jobs, and a more robust local food system. Our SARE project assesses the productivity and profitability of low-input crop systems on a property recently transitioned from commodity crop production in the Missouri River bottomlands. Our data and findings offer region-specific data for production costs, yields, and profits on a per-acre scale.

The team did extensive research on varieties, methods for planting, weeding, harvesting, post-harvest handling, and marketing prior to the final crop selection and layout. We initially selected potatoes, sweet potatoes, butternut squash and dry black beans for our assessment. We planted potatoes in late March and sweet potatoes, butternut squash, and black beans during the first weeks of June. Shortly after planting, we lost our black bean crop to herbicide drift. We had another acre in watermelons at the site, so we chose to add that crop to our assessment in place of beans.

Our research approach involved extensive data collection throughout the farm season. To start, we documented all inputs associated with our production system for each crop, including land rent, seeds, pest control, fencing, irrigation, and small equipment such as hand tools. Each member of the group also tracked tasks and time dedicated to the farm in a shared spreadsheet. This record later allowed us to calculate labor demands for each of our selected crops. During the growing season, we recorded harvest yields and sales of all marketable produce. Post-harvest, we added input costs for storage and packaging.

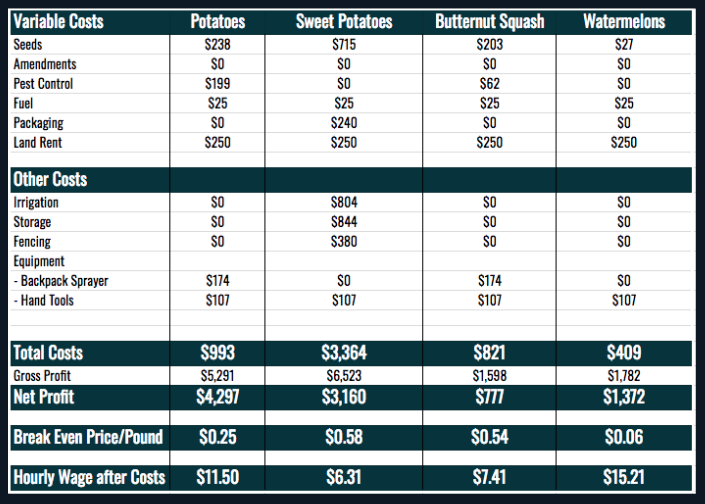

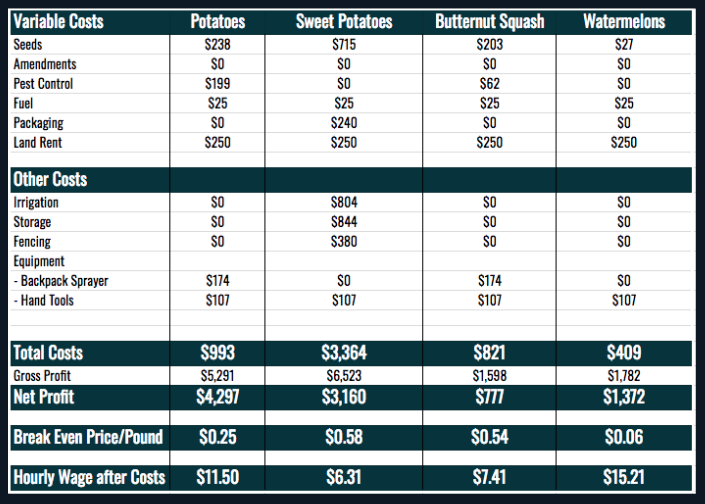

We used the data collected throughout the season to build enterprise budgets for each crop. We also estimated hourly wages based on our task data and net profits. The chart below summarizes the total costs, gross and net profits, break-even prices, and wages for each crop.

Profits per Acre

We used our data to compare the profits per acre from vegetable production to those typically achieved by corn and soybean production. According to the 2017 enterprise budgets provided by the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri, average gross incomes per acre for Missouri corn and soybeans were estimated at $459 and $444 respectively. After operating costs, income per acre was estimated at $135 for corn and $242 for soybeans. The gross and net profits in the chart above are our comparable profits per acre for potatoes, sweet potatoes, butternut squash and watermelon. In all cases, our profits were higher.

Jobs

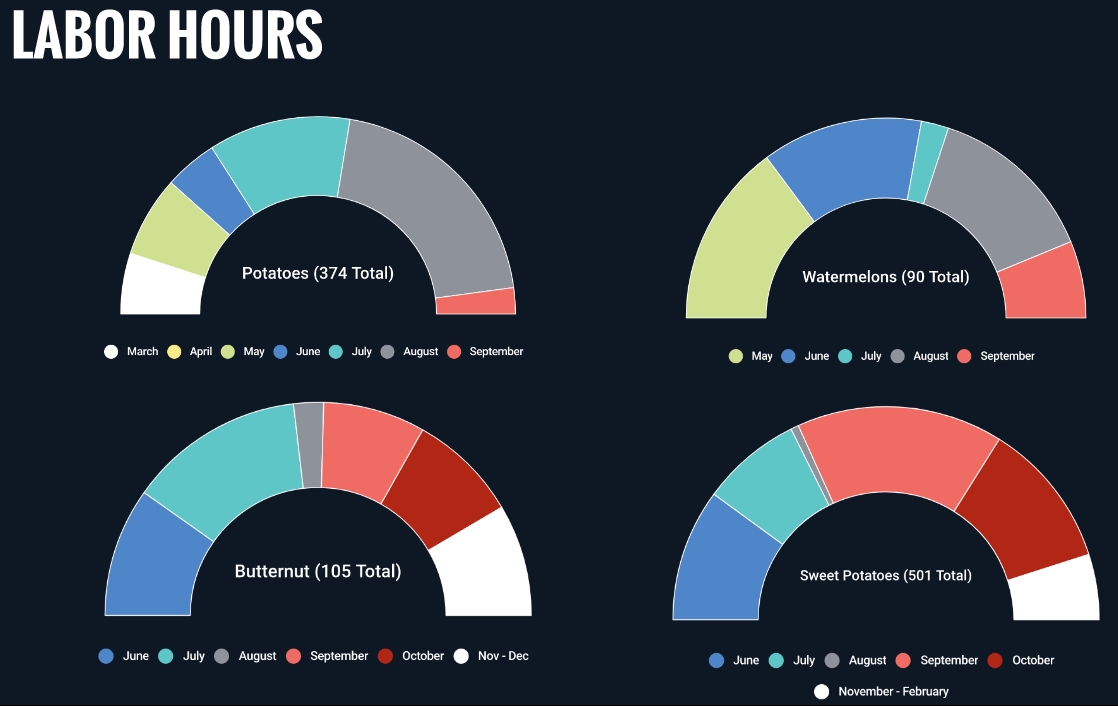

The four farmers participating in this project worked a collective 1,070 hours from the time the field was prepped in March until the last produce was delivered in February of 2016 - approximately 27 full-time weeks.

From our task data and net profits, we were able to calculate the hourly wages for participating farmers. These varied greatly based on the crop, ranging from $6.31 for sweet potatoes to $15.21 for watermelons, with an average of $8.98 across all crops. We compared these figures with MIT's Living Wage Calculator. In Missouri, minimum wage is $7.85 and a living wage is considered to be $10.76. We fell somewhere in between these two figures, though it's worth noting that there were many lessons learned - detailed in the latter sections of this report - that would likely lead to greater efficiency, improved production, higher profit margins, and better wages in subsequent years of farming. As of 2018, two of the four participating farmers have gone on to farm full-time, one part-time, and one is no longer farming.

Local Food System

We grew and harvested approximately 18,000 lbs of produce in 2015. We marketed and sold all of it within 150 miles of our farm. Initially, we focused on Boone and Cole counties in Mid-Missouri. Later in the season, we expanded our marketing to the St. Louis area. Our primary market was wholesale to restaurants and grocery stores in Columbia and St. Louis. We sold a small percentage of our produce through an online shop and local farmers markets. Much of our produce was sold at a premium price. Our buyers were representative of a new wave of restaurants and groceries that have no problem paying a higher price for local produce, because its quality and freshness sets them apart from other businesses. Also, many successful restaurants and specialty grocers we work with agree that sourcing locally is an ideal way of doing business because it keeps money in the local economy, provides income for honest producers and strengthens community.

Economic benefits: To assess the economic benefits, we collected data on vegetable crop yields and compared them to similar cropping operations around the country. We created cost-of-production estimates for each crop and used them to build locally-relevant enterprise budgets that we share with farmers in our community. We calculated our average per-acre return for the crops and compare them to commodity crops grown on similar soils, demonstrating the higher profits achievable through diversified vegetable production. Our final figures for labor hours needed to operate the vegetable cropping system support decision making around hiring laborers or pursuing farming as a part or full-time occupation.

Social benefits: To catalog the social benefits of our project, we recorded attendance at the on-farm and community field events. We also recorded attendance at “cropmob” workdays, where people from the local community were invited to help with labor-intensive days such as planting and harvest. Numbers from our website and social media accounts gauge interest in our project and demand for locally-grown vegetables in our region. We presented our findings at two events - one a public presentation in Columbia, MO and another at the annual Mid-America Organic Association Conference in Independence, MO. Our outreach efforts strengthen connectivity with the broader farming community. We know that livelihoods in small-scale sustainable agriculture provide people with a greater connection to the land on which they live and their local food system. Our project relied heavily on the involvement of friends, family and community members, and we continue to engage interested parties across the region in a conversation about the feasibility of increasing local food production in Mid-Missouri.

Outreach: We collaborated with the Missouri Young Farmers Coalition (MOYFC) and the Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture (CCUA) to organize two on-farm educational events in the summer of 2015 and to host a community-wide event to present our results and demonstrate, distribute, and train farmers to use the budget enterprise models. We built a simple, accessible webpage that will be home to periodic updates, various multimedia content, and eventually a summary report and the customizable budget enterprise models. The results of our project, including the summary report and associated enterprise models, will be posted on our own site, linked via partner websites, shared via email across several local email list serves focused on small scale agriculture and local food, and disseminated via social media. Follow-up support will be provided to anyone interested in learning more about the crop systems, budget tracking procedures, or enterprise budgeting.

Cooperators

Research

Our research approach involved extensive data collection throughout the farm season. To start, we documented all inputs associated with our production system for each crop, including land rent, seeds, pest control, fencing, irrigation, and small equipment such as hand tools. Each member of the group also tracked tasks and time dedicated to the farm in a shared spreadsheet. This record later allowed us to calculate labor demands for each of our selected crops. During the growing season, we recorded harvest yields and sales of all marketable produce. Post-harvest, we added input costs for storage and packaging.

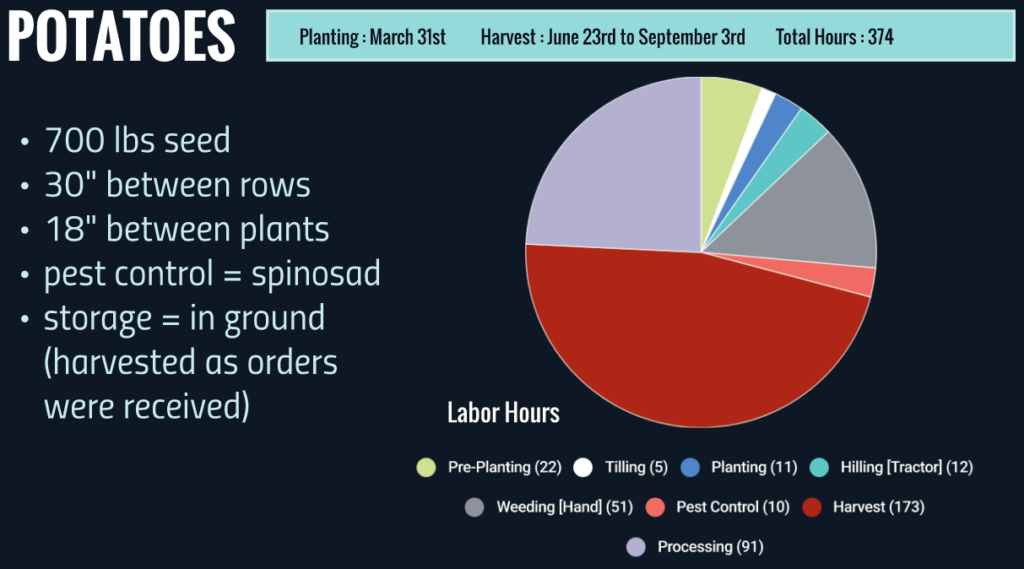

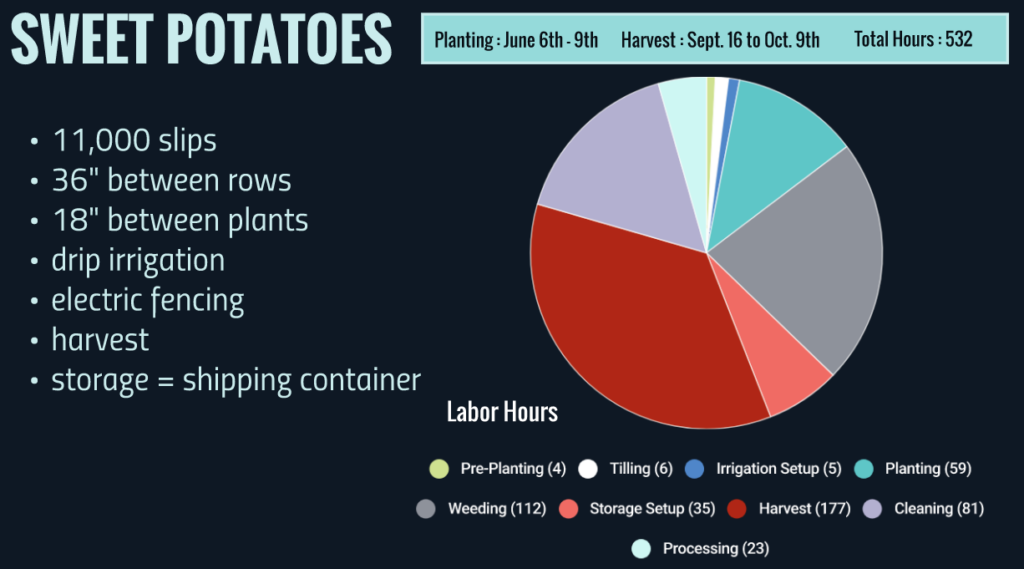

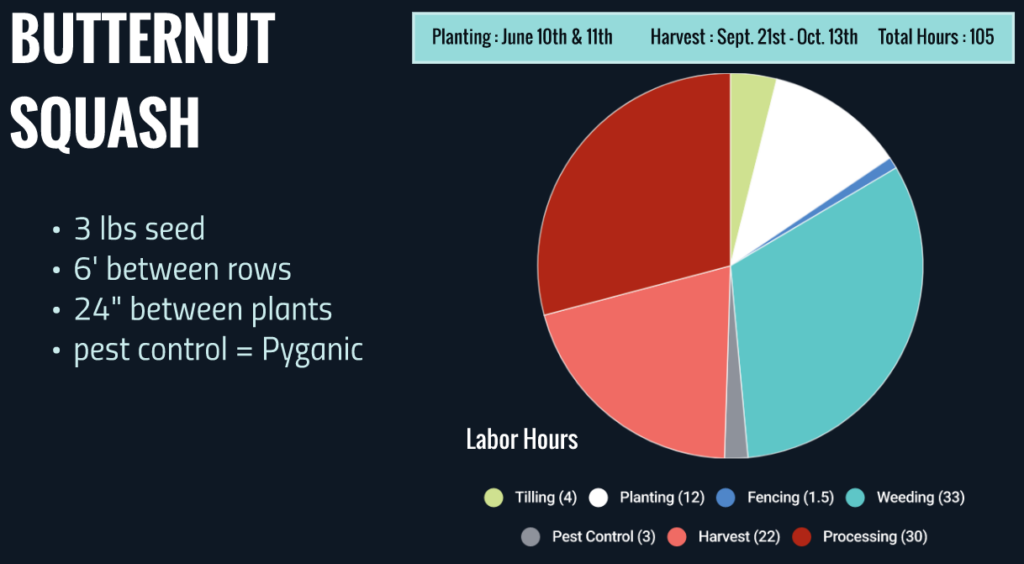

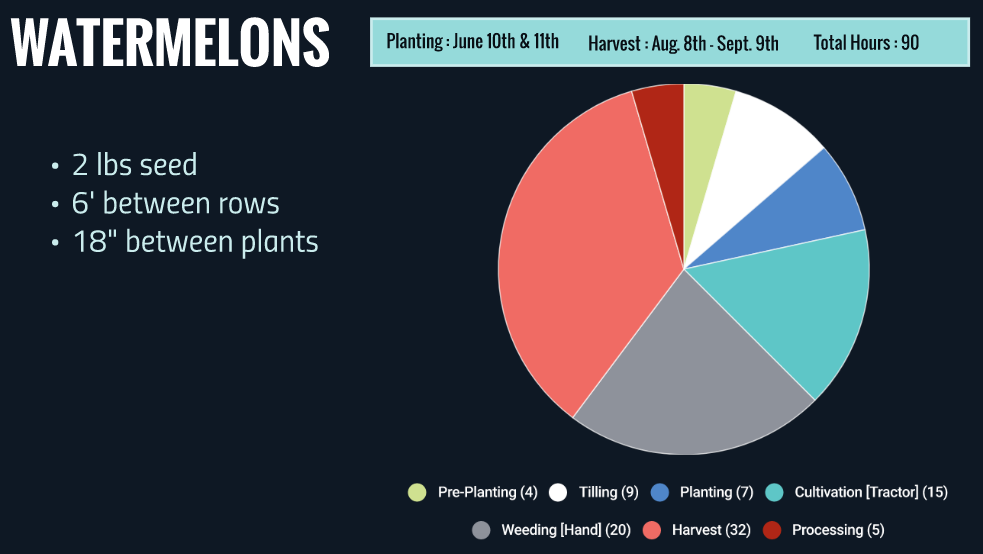

The following images display details related to our production system, planting and harvest dates, and labor hours for each crop.

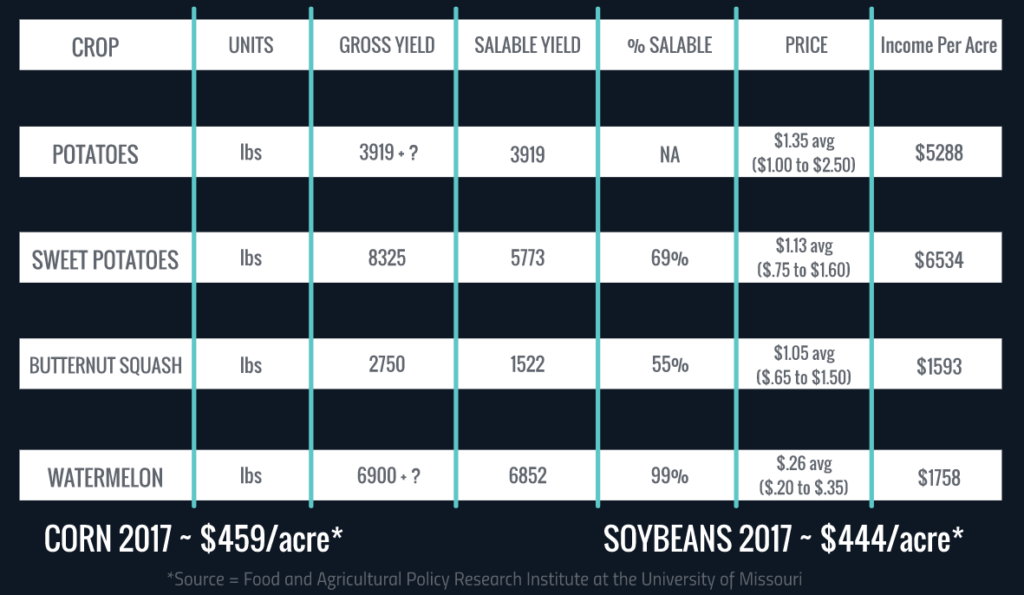

The following chart displays gross and salable yields for each of our crops, along with the prices we were paid for the produce and gross income per acre. There is a question mark for the potato gross yield because we failed to get an accurate estimate of culled products. There is also a question mark for gross yield in the watermelon category. The landowner historically grew a watermelon patch for the community, and many people were accustomed to picking up a melon or two directly from the field. We witnessed this on several occasions, but we are unsure how many watermelons left the field via this route.

We used the data collected throughout the season to build enterprise budgets for each crop. We also estimated hourly wages based on our task data and net profits. The chart below summarizes the total costs, gross and net profits, break-even prices, and wages for each crop.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

We used on-farm gatherings, social media, a website, and off-farm events to share the details and results of our project.

- One field day was held at the farm to tour interested parties around the operation. We had representatives from Lincoln University Cooperative Extension and the Columbia Farmers Market as well as interested beginning farmers in attendance. In total, 13 people joined our group for the field day. Great discussion was held on best practices and issues of plant health.

- We had several workdays at the farm where young farmers lent a hand with the operation. This was doubly beneficial – we had extra help and an outreach opportunity. Early in the season, we had crews of volunteers to help plant potatoes and sweet potatoes. During harvest, The Columbia Center For Urban Agriculture introduced us to a crew of 10 from the Americorps National Civilian Community Corps that helped us dig sweet potatoes on multiple occasions. The corps members were from mostly urban areas across the U.S., and many of them had never been on a farm. In exchange for the help, the Americorps group then donated a percentage of the day’s harvest to the Central Missouri Food Pantry on CCUA’s behalf. The experience was overwhelmingly positive and helped build relationships in the community.

- Meetings with growers on and off site were held informally at several points through the season. These meetings were helpful at diagnosing plant health issues, comparing weed control strategies, and making plans for harvesting and crop storage.

- We established an online presence with website and Facebook group. As of December 2017, Mid-MO Growers Group has 80+ followers. Our website has 466 visits, 353 unique visitors and 1174 page views.

- In 2017, we held a public presentation for the Mid-Missouri community. We shared our enterprise budget findings and other lessons learned. This was advertised primarily through Facebook - on our page and in related groups such as the Missouri Beginning Farmers Program. Approximately 90 people expressed interest in attending. The actual number of attendants was 10.

In 2018, our research findings were shared at the 10th annual Mid-America Organic Association (MOA) Conference in Independence, MO. We will also post a suite of customizable spreadsheet tools online, including enterprise budgets and worksheets for electric fencing, drip irrigation, and our sweet potato curing and storage facility. Moving forward, we hope to find additional opportunities to share our results with the community. These may include podcasts, workshops tailored to specific farming groups in the region, and poster presentations at upcoming conferences.

Learning Outcomes

This SARE grant allowed us to collect and analyze a wealth of valuable data to inform decision-making in future farm enterprises. Our research is relevant for a range of common topics in vegetable production, including:

- Estimated input costs, labor demands, yields and profits per-acre of production

- Challenges associated with transitioning cropland formerly in commodity production

- Short-term and low-cost irrigation, fencing and storage options

- Expected and achievable price ranges for produce sales

- Wholesale marketing and direct sales

- Alternative markets for lower grade produce

- Community engagement

Farmer Learning Outcomes

Site

Commodity croplands present a unique set of benefits and challenges for specialty vegetable producers. On the positive side, landscapes in which large swaths of corn and soybeans are planted tend to be flat, previously worked, sod-free river or creek bottom fields that are inherently fertile. Some of the challenges presented by these lands, however, are difficult to manage.

In a low-lying valley dominated by conventional production methods, the strong possibility of herbicide drift puts vegetable crops at risk of spray damage. Whereas there exist methods to mitigate spray drift, there is no way to grow vegetables in these landscapes with 100% certainty that they will not be damaged. This was proven when our entire black bean crop sustained major herbicide damage and had to be culled.

Pesticide spraying in the area also interrupted our work routine. On several occasions, we opted to vacate our vegetable patch while spraying was conducted on a nearby soybean field, presumably to combat the abundant population of Japanese beetles.

Weeds posed a major challenge to production. This is common to all agricultural production systems, of course, but our site was home to a hearty population of the fabled “superweeds” - varieties of giant spiny amaranth that can grow to be 10 - 12 feet tall, with four-inch diameter trunks and six foot branch spread. Uncertainties about past land management and the existing weed seed bank are a challenge when attempting to transition lands to low-input production systems. Well-planned row spacing that allows for mechanical cultivation can be helpful for weed control.

Harvest, Post-Harvest, Storage

Whereas we successfully estimated the size of a farm that can reasonably be run by four people working collaboratively part-time (with minimal use of a tractor), we underestimated post-harvest and storage aspects of our operation. Potatoes were harvested on a weekly basis as new potatoes. This eliminated the need for storage and resulted in minimal spoilage, but it also made washing and drying a regular post-harvest task. Thus, potato harvest was a drawn-out affair that lasted until well after dark on many occasions. Sweet potato harvesting was an intensive process - done by hand to ensure minimal bruising of the tubers. This required a large investment of labor but resulted in a high quality product and minimal crop loss. With sweet potatoes, we encountered major storage challenges initially.

We needed a large, pest-proof, temperature and humidity-controlled environment to effectively cure and store sweet potatoes for quality concerns. To solve this, we rented an 8’ x 20’ shipping container that we insulated and outfitted with a climate monitor, heater and humidifier. It worked wonderfully, but cost time and money to solve last-minute.

Butternut squash were field-graded, crated, and kept in minimally-heated storage at the end of the season. In hindsight, the crop was graded too strictly, and a fair percentage of the total yield was not brought in for sale. Watermelons were typically harvested, processed, and delivered same-day, minimizing the need for storage space.

Marketing

Finding an appropriate niche in the market is among the most important jobs of a small farmer. The vast majority of our produce was sold wholesale to grocery stores and restaurants who were pleased to have abundant and reliable supplies of local produce.

There are a number of benefits to dealing directly with a variety of local wholesale buyers. First, producers can avoid middlemen and aggregators to collect the full price for their goods. Direct marketing is no small task for producers who are already stretched on time and resources. In order to compete in the wholesale market, the mid-size producer must develop the professionalism, customer service, reliability and consistency that buyers expect from existing aggregators and distributors. This is challenging, but in our observation it is a worthwhile endeavor for building a functional, sustainable and profitable local vegetable enterprise.

Second, producers can gain an understanding of the quantitative and temporal aspects of market demand that are indispensable in planning future farming activities. By understanding who wants which products and when they want them, producers can effectively plan their farming operations to be efficient, effective and targeted to the demands of the local food system. This cuts down on wasted space in the field, wasted time and wasted food.

Third, when a producer develops a working relationship with local restaurants, they can reduce waste and find good markets for second-quality produce. For instance, a significant number of our potatoes, butternut squash and sweet potatoes were of good eating quality but were unusually shaped or superficially blemished from pest damage - traits that might cause them to be culled in standard commercial grading systems. Our restaurant customers were glad to buy wrinkly butternut squash, potatoes with wireworm holes, and sweet potatoes with cut and cured ends for a slightly discounted price. Consequently, our operation was able to sell many hundreds of pounds of produce that would normally be cast aside.

No discussion of marketing would be complete without addressing the inevitable waste stream from a vegetable farm. Many times throughout the year we took boxes full of #2 and #3 vegetables to the Central Missouri Food Pantry, some of which were saleable and some of which were just below our #2 standard but still of acceptable eating quality. They weigh the produce and keep a running total of our donations. We were glad to be part of the food pantry’s impressive contributions to those people in our community who need access to food. Over time we have developed a very friendly relationship with the staff at the food pantry, and we plan to make donations to the food pantry in the future as part of our operation.

If a motivated farmer, landowner or organization wanted to start a bottomland vegetable farm, we would definitely share these research results with them and encourage them to begin producing vegetables. We feel that there is vast room for growth in the market for locally-grown wholesale produce. We'd recommend investing a significant amount of time in planning prior to planting - optimizing the farm layout for labor efficiencies and plant spacing. We would also recommend that farmers identify markets and buyers prior to crop selection and planting.

Project Outcomes

A slightly more mechanized system of production that still maintains a low-input model would be interesting to study. Our results showed that weeding and harvest were the most time-consuming factors. Some basic mechanization in the weed control realm, particularly mechanized in-row weeding systems, would reduce weeding time and likely speed up harvest time. Consequently we could expect yields and hourly wages to increase. Such investments in in-row mechanical cultivation are relatively inexpensive and could greatly affect the profitability of a farming operation.

A new wave of farmers is discovering the value of walk-behind tractors, particularly David Bradley, Planet Jr. and Bolens brands. These low-cost pieces of equipment allow for bed preparation, precise cultivation and simple mechanical harvest of a range of root crops. They don't have a PTO, so all pull-behind implements are passive mechanical tools that farmers can obtain and modify to their purposes or even fabricate using old designs and pictures. This exciting category of machines could easily scale to the 5-acre scale. A study of walk behind tractors with innovative cultivation and harvest tools for the low-input, low-capital farmer could be very beneficial to farmers looking to scale up and farm smart without incurring massive amounts of debt.