Final report for FNC15-983

Project Information

WORK ACTIVITIES 2015

We spent just under 50% of the project funds up to this point, mostly for personnel and honeybee package purchases. We purchased package bees in the spring, drove downstate to retrieve them and returned and raised the colonies all summer. Most did well, but we certainly had some attrition - causing us to rethink using 4 hives for 7 treatments. Based on our experience, at this point we’ve decided to adjust our controls and tweak our treatments, potentially using 3 colonies per, rather than 4. We are going to do pole barn, straw bale, shed, hoop house, and carport (instead of calf hutch) and use one control wrapped in a Bee Cozy (rather than roofing paper) and one control with no protection. These adjustments are based on local beekeeper feedback (no one had ever had a calf hutch on their farm, but many had carports), and the Bee Cozy product, though more expensive than roofing paper is gaining in popularity and ease of use far exceeds that of roofing paper.

As we have filed an extension, we have postponed the official data collection and winter shelter research until Winter 2016/17 due to the abnormally warm fall and early winter here in Michigan. We want our work to be representative of more typical winters, and not clouded with an asterisk. Our extension request explained that we would like an 8-month extension due to the unusually warm weather this winter and the confounding variables that it may add to our research project. We are concerned that our Upper Midwest Cold-Weather research project for honeybee over-wintering would produce less meaningful results given the abnormally warm weather and add an unnecessary asterisk to the project and its resultant findings. We want results that are helpful to fellow beekeepers and intend to test our shelter options in a more "traditional" winter environment that features more extended periods of cold and more traditional overwintering behavior. We recognize that extreme weather events such as this may become more normal with climate change, but would like to give it another shot in the 2016-17 winter.

Our new end date requested, [and later approved] was October 15, 2017.

RESULTS SO FAR

Touched on this a little above, but we have learned that 4 hives per treatment may be overkill; we’re going to try 3. Calf hutch is not realistic given beekeeper feedback; we’ve switched to carport. Roofing paper is cheap, but rarely used due to difficulty of application and minimum quantity available; we’ve substituted the Bee Cozy. Also, the effect of varroa mites on winter survival is severe, and we are developing a comprehensive measurement and treatment plan in an attempt to get colonies on a level playing field before going into winter.

Furthermore, even though the formal research and recording is postponed until next winter, we did put a dozen hives in our pole barn this winter, and a handful in a shed, and thus far, we’ve had over 90% survival in pole barn, 50% survival in shed (mite pressure is a problem), and under 50% survival outside exposed. This is enlightening and encouraging, so we are excited to see what 2016/17 brings. Not only this, we were concerned about how to manage honeybee access to the outdoors through the pole barn, but tested a few methods of entry and feel confident that we can present a realistic solution for this challenge.

WORK PLAN FOR 2016 /2017

Our work plan for 2016/17 is very similar to the original grant proposal, just one year later. The tweaks to the plan have been detailed above, and we think that we will be better researchers next year since we used this winter as an unofficial dry run to test out our systems and processes. We are cautiously optimistic and hoping for an average winter!

OUTREACH

Though the project is officially postponed until Winter 2016/17, we have discussed our approach and ideas with our local beekeeping club throughout the winter. We’ve received some feedback, and have even inspired about a half-dozen other beekeepers to start experimenting with building shelters for their hives. This has been a great side-effect and we hope to continue the unofficial research alongside our more formal project.

This project will evaluate the cost, success, and management considerations (labor, equipment, scalability) for each of five different shelter options with a two-part control. The shelters were selected based on likelihood of on farm availability and degree of protection. To derive meaningful results and account for hive variability, four colonies will be placed in each of the five shelters. The five shelters are: 1) straw-bale enclosure, 2) calf hutch, 3) unheated hoophouse, 4) standard shed, and 5) an unheated pole barn. The two-part control consists of four hives with no protection whatsoever, as well as four hives wrapped as one unit in a roofing paper-style pallet wrap – the most commonly suggested over wintering technique.

This project acknowledges the tremendous importance of managed honeybee colonies as part of our agricultural system and aims to provide concrete data and accessible conclusions to be shared with beekeepers of all sizes interested in ecologically sound, ethical opportunities to achieve and/or enhance profitability.

Cooperators

Research

As stated from the outset, our goal in this project was to evaluate the cost, success, and management considerations (labor, equipment, scalability) for each of five different shelter options with a two-part control. The shelters were selected based on likelihood of on-farm availability and degree of protection. Our idea was to test five different shelter options, which we eventually reduced to 4 options and a two-part control. The four shelters were: 1) straw-bale enclosure, 2) unheated hoophouse, 3) standard shed, and 4) an unheated pole barn. The two-part control consisted of three hives with no protection whatsoever, as well as 3 hives wrapped in individual Bee Cozys.

To reduce the potential for other winter threats we did a few things to every hive to insure better survival. All hives were treated with Oxalic Acid via vaporizer for varroa mites in late October to kill off mites heading into the winter. All hives received mouse guards made of hardware cloth. All hives received 5-7 pounds of loose white cane sugar atop newsprint paper inside of a 4" 'attic' above the highest honey super. This 'attic' had holes drilled for airflow and 1" 'blueboard' insulation above the sugar pile to reduce condensation.

After a somewhat mild fall, on December 4, 2016, three of us (Anne, Brian, and apprentice) prepared all hives for transportation from their summer field locations on our farm to their shelters. Because we wanted consistent results, we placed fewer hives in some shelters than we initially thought, but we did not want weaker hives to skew the results. On 12/4/16, we placed 3 hives inside the straw bale enclosure, 2 hives in the hoophouse, 3 inside the shed, 10 inside the pole barn, and in the control - 4 wrapped in Bee Cozys outside, and 3 outside unprotected. This made for 25 total colonies that were being compared with one another.

So WHO survived best?! This was the question we were asked dozens and dozens of times throughout the course of our project. From the outset, our hypothesis was that the best environment would be the unheated pole barn. It is worth noting that we deliberately did not test any heated shelters as a part of this project. This was to ensure realistic results, not influence the bees' natural temperature management behaviors, and keep costs down for beekeepers.

The results are as follows:

Straw Bale Enclosure: 0/3 Survived = 0% Survival

Hoophouse: 2/2 Survived = 100% Survival

Unheated Shed: 2/3 Survived = 66.7% Survival

Unheated Pole Barn: 9/10 Survived = 90% Survival

Outside Control - Bee Cozy: 4/4 Survived = 100% Survival

Outside Control - Unprotected: 0/3 Survived = 0% Survival

Overall Colony Performance: 17/25 Survived = 68% Survival

So what does this mean? Well - there's a bit to unpack and some nuances worth noting.

Seeing all of the hives die off inside the strawbale enclosure came as a surprise. We thought this would be the most well-insulated of all shelters. And as it turns out, that was mostly true, but it came at a cost. On a cold day, these hives were likely the most protected from the elements. But on the few warmer or sunnier days, these hives remained the coldest. As most beekeepers know, those few sunny winter days can be essential for colony survival as it allows them to break cluster, move to new honey reserves in the hive, and take off on cleansing flights. None of this could happen inside the dark, damp, insulated environment of the strawbales. Furthermore, the total enclosure showed signs of mold and excessive moisture on the exterior of the hives when deconstructed in the spring. Perhaps this shelter could be improved with an alternative 'roof' material other than strawbales.

As for the hoophouse, we are the first to admit our surprise that both of these hives survived. We were concerned, like many others, that this environment could prove disorienting to the bees and lead to seasonal confusion and excess activity. And while these hives were by far the most active (leaving the hive on every sunny day), they did manage to survive and thrive. We were concerned that they would leave the hive and fly into the walls of the hoophouse and become confused and die. The bees DID leave the hive and fly into the walls, but inevitably they would all make their way back to the hive before dark. They could take cleansing flights almost whenever they pleased, and they were able to move within the hive as needed. One major point of note, due to these hives' increased activity, they were the first to consume most of their honey reserves and required the earliest and most frequent spring feeding to stay alive. They also got off to a fast start in the spring.

Seeing two of three hives survive in the shed seems fitting. This option felt the least involved and required no special attention. The shed had natural cracks that they used as entry/exit points, and it was able to warm up a little on sunny days but protected from the wind on cold days. For beekeepers with more than a couple hives, the size of the shed can and will be a limiting factor. Sheds can also be popular overwintering spots for other critters, so adequate rodent control is essential.

Our hypothesis was that the unheated pole barn would be the best shelter, and we put ten hives inside for just that reason. And although all of this data is from the 2016/17 winter - we beta-tested the pole barn in the 2015/16 winter with 10 hives as well. Both winters saw 9 of 10 hives survive. This is encouraging. A couple logistical notes on parking bees in a pole barn. If you have windows, it is best to black them out - we stapled weed fabric on the windows to ensure darkness. Unlike in the hoophouse, bees would get stuck on the windows in the pole barn and struggled to make it back to the hives. Furthermore, indoor/outdoor access was a major concern of ours that needed to be solved. Thinking of the pole barn like a kennel, we decided that we could let all of the hives share one entry/exit point. We accomplished this by not shutting the overhead door all the way. The garage door was 8' wide, so we placed a 6' long 2x6 underneath the door to allow a 2' by 2" opening between the floor and the garage door. This worked out wonderfully and served as the main thoroughfare for bees coming and going. On sunny days they would find the slit of light under the door and fly outside on their cleansing flight and then return inside. Other than that, the darkness encouraged the majority of bees to remain inside the hives. Additionally, for all shelters, we recommend putting your hives on pallets, even if only 2 hives per pallet. But inside of the pole barn, this was essential. It allowed us to move hives with a hand-pushed pallet jack within the pole barn so that we could still use the pole barn throughout the winter and we could arrange more hives inside the barn. This shelter was a crowd-favorite, and definitely presented the most potential for scaling up. Obviously, it costs more to construct a pole barn if you're starting from scratch.

As for the outdoor controls, we were anticipating about 50% survival based on our previous experience for the past four years. That being said, we were genuinely shocked to see that 4 out of 4 colonies in the Bee Cozy survived the winter and 0 out of 3 unwrapped hives survived. This almost seems too good to be true, but the numbers don't lie. At approximately $25 each, the Bee Cozy is by far the best bang for buck of all of the treatments and would be an investment well worth making for the small scale beekeeper. It's cheap insurance and requires no moving of live bee colonies, or additional infrastructure. And unlike the straw bales, it seems to insulate the sides without over-protecting the hives allowing natural behavioral patterns to maintain some normalcy.

Going forward, we are planning to place most of our hives inside the pole barn each year. It felt the most appropriate and it was certainly the easiest shelter to check on the status on the hives throughout the winter. We will probably place the Bee Cozy on the hives inside the pole barn just for good measure. It seems like the best of both worlds! We will also leave about a third of our hives outside year round with the Bee Cozy. Some of our hives are in harder to access locations, so moving them is not as desirable. We believe that just adding the Bee Cozy should be adequate. Why not skip the pole barn altogether and just use the Bee Cozy? It's a fair question, but we felt like the hives in the pole barn, in addition to have equal survival rates, seemed to consume less honey reserves over the course of the winter. We will need a couple more winters to corroborate this observation, but if having them fully protected inside the barn provides excellent survival AND reduces honey consumption over the winter we are able to reduce the risk of starvation AND potentially harvest more honey in the fall.

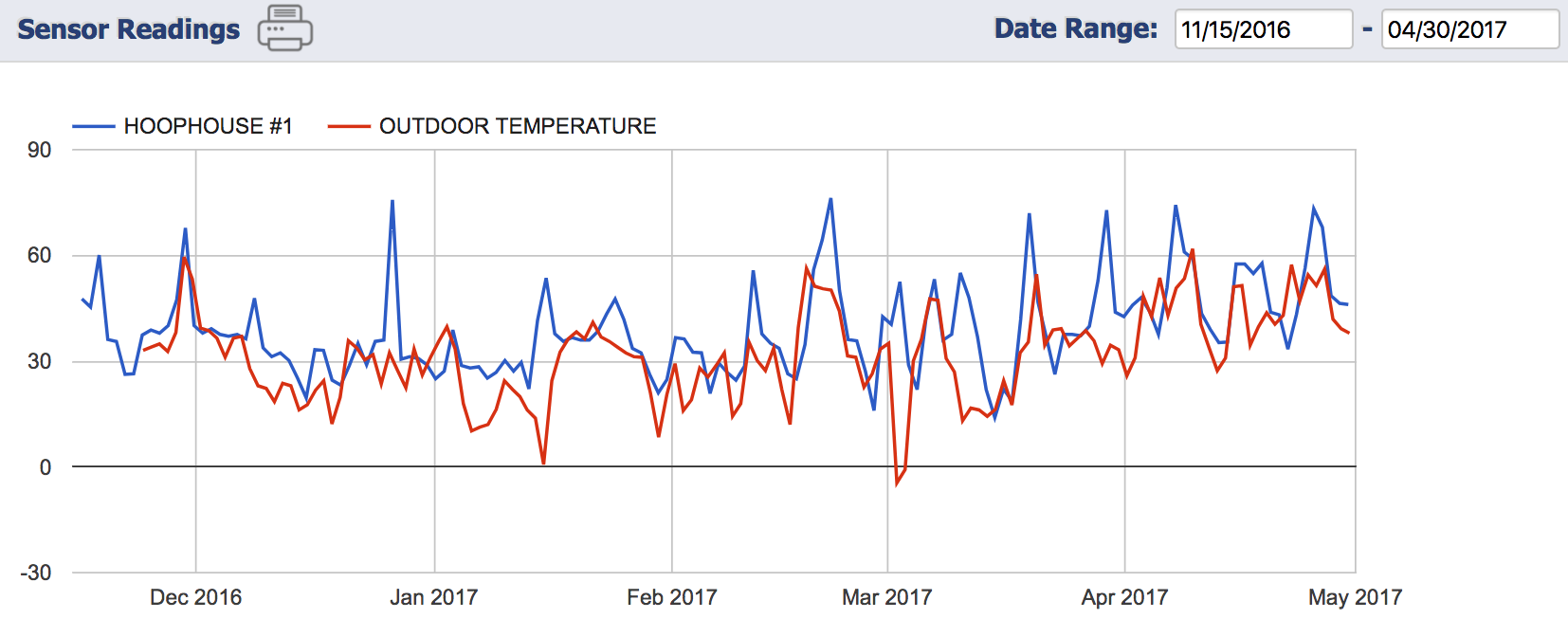

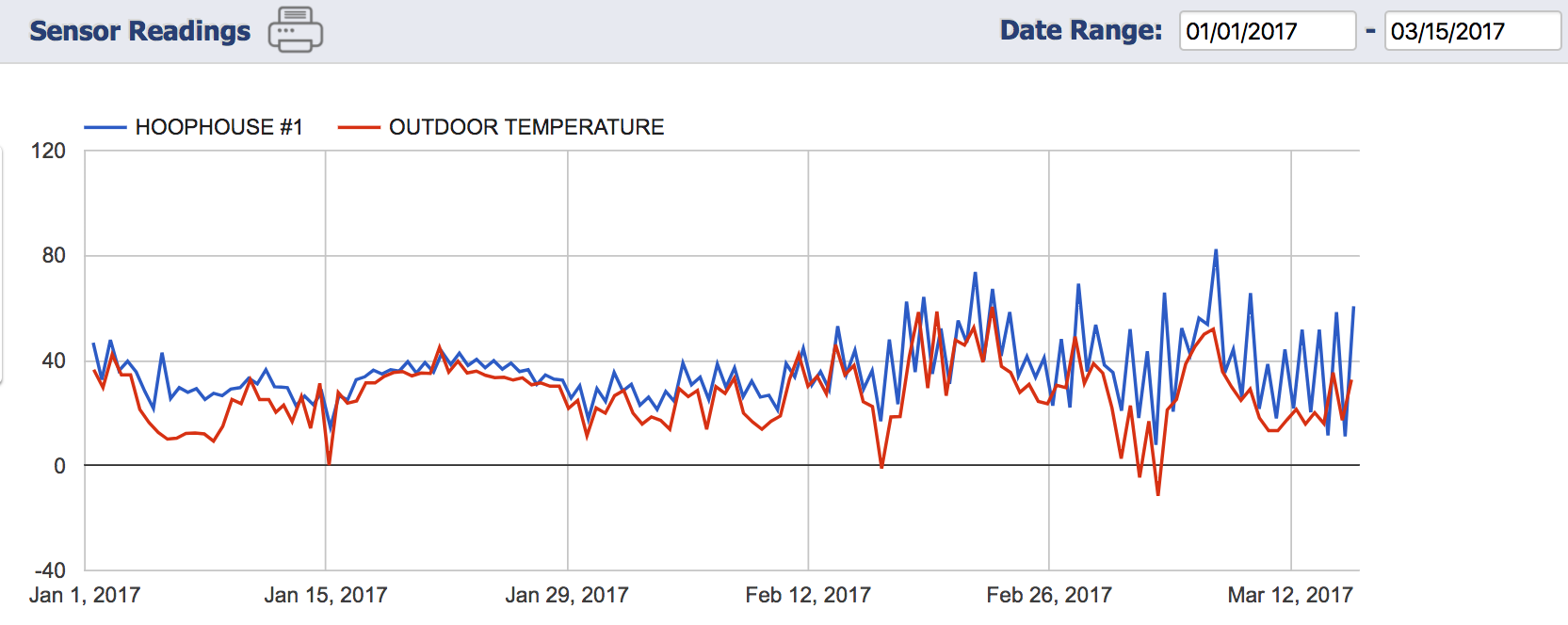

Below are some data logging charts showing outdoor temperatures for the duration of the project. In addition, we included the temperature recording from the hoophouse that housed the two hoophouse hives. That hoophouse was 30' x 144' and proved to be an excellent regulator of temperature spikes. You can see on each of the coldest nights this winter, the hoophouse stay disproportionately warmer than outdoor temperatures due to its air mass and insulation. Helping to regulate those cold spikes is no doubt one of the most important advantages of any shelter-based overwintering strategy.

Outdoor and Hoophouse Temperature Comparison January-March 2017

Outdoor and Hoophouse Temperature Comparison November - April 2017 (note the 4 major outdoor temperature drops regulated by the hoophouse enclosure)

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

The most common method for sharing our project with others was during farm tours, beekeeping workshops, bee club meetings, and individual and social media interactions. We had about 10 other beekeepers reach out to us after some of our social media posts about the Grant research or from the SARE website with whom we shared our findings to date and tips for success. We held 18 different monthly beekeeping club meetings on our farm, and attended 20 other monthly meetings over the course of the project and discussed our research and current results in depth at 6 of them, typically in the fall to prepare for winter and in the spring to share results. This was of great interest to our beekeeping peers and has inspired other ideas amongst our neighbor beekeepers. We hosted approximately 12 farm tours during the course of this project for groups ranging from 10-75 people, while everyone on the tours were not beekeepers, we always covered our beekeeping practices and share SARE project updates on each tour. Our grant award received local press on the Television, and as such, many members of our community have become familiar and interested in the nature of our work and the results. Similarly, we've been asked to speak about our work with bees and the project at local conferences, garden clubs, and lecture series all across northern Michigan. These speaking engagements range from 15-120 individuals per gathering and have garnered a lot of attention for the plight of the bees and the nature of our project. We know that our efforts to share our work on beekeeping and the overwintering strategies have reached thousands of people, and are happy to report that we've been able to help the collective overwintering survival rates of our local small-scale beekeepers in the process as well.

Learning Outcomes

We learned a lot from this grant - in particular, it takes more time to execute a seemingly simple research project than anticipated and this topic resonated with at least as many, if not more beekeepers than we anticipated. Additionally, it reminded us of the intelligence of honeybees and the challenges of winter.

This grant has affected our farm operation in a significant manner, in that we plan to no longer leave any honeybee colonies outside over the winter going forward. We plan to move 100% of our hives into our pole barn each winter - we've dubbed the pole barn the "Honeybee Hotel" as it will be home to dozens of hives each winter.

We did overcome our identified barrier, but not without a lot of losses and expensive lessons. This budget does not do justice to the 'real' costs of losing a colony of bees. Not only do we have a replacement cost for the colony, the lost production the subsequent year can be staggering. While we knew we needed to test out multiple treatments to see what worked, it was tough watching the hives in the pole barn and hoophouse thrive and not be able to just move all of the colonies inside!

As mentioned, the major disadvantage of implementing a project such as this is that it can be very disruptive to an essential income stream for our farm business. In 2016 we experienced an 85% decline in honey production and harvesting compared to 2015. And at the same time, we knew we had to put many colonies in challenging situations to test our hypothesis. Had we not committed to such a research project, we can comfortably say that we would not have risked losing any colonies and would have likely made the decision to put them all inside of something. This of course, is speaking with the benefit of hindsight. Nonetheless, the biggest disadvantage is how much risk exposure we put ourselves through with this kind of project. The biggest advantage is that we now have solid information with which to inform our future decisions and those of other beekeepers. And that is far more valuable in the long term.

If asked for more information concerning what we examined, I would tell other farmers and beekeepers to know that the shelter is just one part of successfully overwintering your bees. Equally if not more important is checking and treating for varroa mites, ensuring adequate food reserves, and maintaining good ventilation. Perhaps naively, we thought simply moving a hive inside of shelter might solve most of winter's challenges, and while it certainly does help, there are other best management practices that must also be followed for true success.

Project Outcomes

Though we did not have the idea or the budget for more instrumentation, it would be interesting to build in regular infrared imaging and colony weighing as part of ongoing research. The weights of a hive continue to become a very strong indicator of various hive behaviors and circumstances and future data collection could lead to more informed decision making.