Final report for FNC16-1060

Project Information

Honeybee Farm (Farm Service Agency Tract 9093 in Ann Arbor, MI) is a very small family farm comprising 10 acres, about 6 of which are arable. Up until 20 years ago, it was part of a larger adjacent farm, which has sometimes continued to lease the fields for feed corn or soybeans. For the last 4 years, however, we have kept 2 horses on the property, grown exclusively hay, and recycled the horse manure into fertilizer for the fields. Additionally, we maintain ten beehives that give the farm its name. For this project, we converted 1/2 acre of hayfield to hops production.

Michigan is a superior location for hops production since it encompasses the ideal (for hops) 45 degree latitude and is also one of the leading states for craft beer output. Nevertheless, hop acreage hasn't kept pace with beer production, due in part to the high capital costs of hops production.

A short trellis system has the potential to reduce capital and other costs and bring hops production within reach of small farmers like ourselves. However, previous studies of short trellis systems have focused largely on less marketable dwarf varieties. Therefore, this study examined the suitability of the most common hops cultivar in Michigan craft brewing, Cascade, and further looked at several parameters to optimize yield (notably, row spacing, plant spacing, and trimming of apical meristems) while utilizing organic methods.

Overall, the results demonstrate that a short trellis system is a viable alternative for hops production in Michigan. We recommend posts at least 10 feet tall with 10' row spacing, 36" plant spacing, but no trimming of apical meristems.

These are the objectives of this study:

1) Determine the suitability of a short-trellis system for growing hops in Michigan while applying sustainable, organic methods;

2) Validate the presumed benefits of short trellising including the following:

- Lower capital cost to install;

- Reduced labor costs (installation, crop inspection, harvest);

- Reduced harvest mechanization (can access bines from pickup bed);

- More efficient spray application;

3) Determine recommendations for the following:

- Post height above ground;

- Row spacing;

- Plant spacing;

- Manually trimming apical meristems as bines approach the top wire to promote side growth;

Most of the evaluation is based on practical observations from our experiences throughout the two year study. In addition, a small Design of Experiments analysis was made based on the plant and row spacings and yields.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

Research

Planting Layout:

We planted 400 new Cascade hops plants for the study in spring of the study's year 1 (of 2). Six rows were rototilled 5 ft. wide and 100 yds. long. Spacing between rows and between plants was varied as follows, to evaluate the effect of spacings:

- Rows #2 and #3 employed 10 ft. spacing between rows, where Row #2 utilized 36 in. spacing between plants and row #3 42 in.

- Rows #5 and #6 employed 8 ft. spacing between rows, where Row #5 utilized 42 in. spacing between plants and row #6 36 in.

- Rows #1 and #4 serve as control rows with varied spacings.

Mixed ryegrass and red clover were planted as cover crops between rows. Straw bales were spread for mulch each winter.

In spring of year 1, soil analysis was performed and nitrogen/phosphorus/potassium fertilizer added at recommended rates. Sulphur was broadcast to lower pH which began around 7.0. Following these initial applications, fully organic methods were followed, and only composted horse manure was added for nitrogen later in year 1 and throughout year 2.

Trellis design:

14 ft. black locust poles, for longevity and organic compliance, were sunk every 42 ft. along five of the rows. (The remaining row--#5--was between rows with posts but had none of its own.) 3 ft. deep holes were dug with a towable auger and a mixture of gravel and lime dust placed at the bottom of the holes for drainage. All poles on the outer perimeter were angled outward about 20 degrees to align loading with the post axis, and then they were secured to 48” ground anchors with turnbuckles for future tension adjustment. The ground anchors were spun in manually with a crowbar.

A low height, hi-tension wire was placed 18” from the ground down each row to tie twine to by each plant and to support drip irrigation. The extra row without posts utilized short stakes instead (2’ above ground) to support a low wire.

5/16” 7x19 galvanized cable was strung through eye hooks in the poles (laterally/across the rows). 3/16” 7x19 galvanized cable was strung along the rows, over the lateral cables, and secured to eye hooks at the ends with two cable clamps each. The 3/16” cable was also used for guy wires to the anchors (one at each side pole and two at each corner pole). Galvanized cable thimbles were used at abrupt turns in the cable (for example when reversing direction through the eye hook or at the perpendicular end wire) in order to minimize cable stress points.

Plastic tie straps were tied at the intersections of cables (lateral to longitudinal) to prevent side-to-side motion between the cables while allowing longitudinal motion which occurs as the bines grow and the weight distribution varies. Wires were accessed from a 6’ ladder and from the back of a UTV. Cables were unrolled by supporting the cable spool from the bucket of our tractor loader with binder chains.

Irrigation design:

Residential water was used for low initial cost and expediency. A timer valve was attached to a house spigot. 1” poly tubing runs 550’ to the hop field. A fertigation tank is mounted in parallel. The poly tubing also serves as a header for seven T-valves, one per plant row, that feed ½” pressure compensated drip lines (for even output despite length or slope) with ½ gph emitters.

Plant Care:

Weeding was the greatest challenge. To avoid non-organic herbicides, we relied on labor intensive manual weeding from May through August, either pulling individually or using a weed trimmer. The weed trimmer was much more efficient but care must be taken not to damage bines. We used a brush hog to maintain the ryegrass cover between rows and around the perimeter every other week.

Bines were trained each May, selecting 2 or 3 of the healthiest shoots.

From June, we watered 2 gallons once every 3 days (alternating rows), except when it rained. We also began weekly "scouting" for pests and disease: predominately leaf hoppers, Japanese beetles, spider mites, powdery mildew, and downey mildew.

We applied composted horse manure (produced following the Berkley method of manually turning the pile every other day for 3 weeks) the first week of April and July and once more in October, after the harvest. We applied an estimated 2 tons each time, to approximate a rate of 200 lbs. nitrogen per acre (over our half acre) assuming 0.8% nitrogen content of the horse compost.

One string of sisal twine was also hung at each plant (using clove hitch knots) and the bines that had reached the low wire were trained the same first week of July.

In the second year, we experimented with trimming the apical meristems as the plants reached the top wire to promote side growth, leaving some sections untrimmed for comparison.

Harvesting was conducted manually the first week of September in year 1. The hops were dried and pressed into 2 oz. hop plugs with a hand-made rig (filling a 1.5" diameter PVC tube, and compressing with pipe clamps). In year 2, bines were cut down and taken to a harvester for processing and later dried and pelletized.

Fall cleanup consisted of removing bines (which may otherwise spread disease), mowing, and spraying Neem oil for organic mildew control.

Apical Meristems:

Trimming apical meristems involves clipping the bine below the top group of leaves just as it reaches the top wire in order to promote early transition from vertical to side growth. We performed this in adjacent sections with no discernable difference, although both trimmed and untrimmed displayed similarly acceptable sidegrowth. The following pictures compare the sidegrowth of otherwise similar plants in adjacent sections, with the first clipped just below the top wire vs. the second having reached the top wire without trimming:

Sidegrowth appeared to accelerate once the bine reached the top wire independent of trimming, and it has been suggested to us, plausibly, the when the bine bends down by gravity after reaching the top wire, that is sufficient to transition to sidegrowth.

Yield Analysis:

The primary question was whether yield from the short trellis can be sufficient for a viable production system. The total dry yield in year 2 was 44 pounds compared with 8 pounds in year 1 (or 225 pounds and 40 pounds, respectively, prior to drying).

Nevertheless, due to higher clay content at the east and south sides of the field, 2/3 of the yield came from the most productive 10% of the hopyard. Therefore, those more fertile sections were producing nearly 3/4 pound per plant. With full maturation in the 3rd year of a hops plant, it is reasonable to expect 1 pound dry yield per plant, or 1 thousand pounds per acre, which compares with many full height trellis layouts:

Row and Plant Spacings:

Unfortunately, the unequal clay distribution where we layed out our trellis confounded the results of our Design of Experiments Matrix. It is rather a moot point, because practicality reasons previously discussed dictate a 10 foot row spacing (for sufficient tractor clearance) and 36 inch plant spacing (just sufficient to prevent overlapping and tangled sidearms between adjacent plants) in any case.

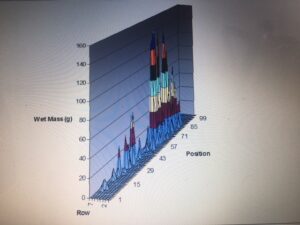

That notwithstanding, here are the DOE results from year 1, which are similar (in relative but not absolute terms) to those of Year 2:

The total Year 1 yield was 3,645 grams:

|

|

Plant Spacing |

|

|

|

Row |

36" |

42" |

Marginal means |

|

8' |

1,369 |

1,844 |

1,607 |

|

10' |

77 |

355 |

216 |

|

Marginal means |

77 |

355 |

|

From the above table, the apparent main effect of row spacing was higher yield at 8’ than 10’, regardless of plant spacing (higher marginal mean of row spacing).

Similarly, from the above table, the apparent main effect of plant spacing was higher yield at 42” than 36”, regardless of row spacing (higher marginal mean of plant spacing).

Nevertheless, the above conclusions require the two factors (row spacing and plant spacing) to be independent. However, having plotted the yield by location, it appears that the farther from the edge of the field (the east and south edges of the hop yard—see 2016 Hop Yield plot below), the more fertile the field. This was observed while working the soil as well—that it was much heavier in clay the closer the plants were to the east and south edges. In restrospect, we would be much better off if the trellis had been set up farther from the field edges. Now it is hoped to overcome this by working the soil more each spring and by increasing Nitrogen application and irrigation.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

We created 9 YouTube videos (search “Honeybee Farm hops” from YouTube.com or click on the links below) receiving over 1,000 combined views. We estimate these have reached approximately 100 hops professionals:

2016:

Hops Short Trellis Project: overview of hopyard design and construction;

Tightening Hops Trellis Wires: tensioning upper wires with the come-along;

Tying Hops Trellis Wires: tying longitudinal wires to lateral wires;

Hopyard Irrigation: overview of drip irrigation design;

Training Hops: tying twine and training a plant on the twine;

Hops Harvest Year 1: harvesting the wet hops;

2017:

Trimming Hops Apical Meristems: promoting early sidegrowth clipping the bines upon reaching the high wire;

Composting Horse Manure: applying Berkley method for making compost;

Using the Wolf Harvester for Hops: separating the cones from the bines with the Wolf harvester;

August 2017 Field Day:

We held a hops production field day in August 2017, with an overview of hopyard setup and techniques, focusing on short-trellis and organic production techniques. We have since learned how to improve upon marketing from this experience, but still managed to attract 7 actual and/or interested hops professionals people to attend.

Learning Outcomes

With respect to our primary objectives:

- We believe that a short trellis system is a viable alternative for the small hops grower in Michigan, when the benefits listed below outweigh the perhaps 1/3 loss in yield per plant compared with a 18' trellis. This is, however, offset by tighter row spacing (10' vs. standard 14') which allows for more plants per acre.

- We concluded 10’ row spacing and 36” plant spacing is most desirable. Closer rows are too tight for a tractor, and closer spacing results in intertwined sidearms. 36" spacing is typical for full-size trellis Cascade growth so greater spacing is unnecessary.

- Trimming of apical meristems does not appear necessary to promote side growth, and the bine folding over the top wire by gravity seems to have comparable effect in transitioning to side growth without any labor required.

-

Validated Benefits of Short Trellis:

- Posts were much cheaper ($18/post vs. $45).

- Posts were much lighter (~75 lbs vs 200+ lbs.). This made them easy to raise by hand, even with a single person.

- Posts were sourced locally, but 18’ posts would have required sourcing from Wisconsin, New York, or Northern Michigan.

- Our hopyard is accessed through a wooded trail. Any larger posts would have required widening the trail.

- Raising the wires was possible from either a 6’ ladder or the back of our ATV. I fell from the ladder once and was spared by the low height (although I probably would have been more careful up at 18’).

- Spot application of Neem oil and the subsequent harvest was similarly accomplished from a 6’ ladder, without investing in any capital intensive equipment.

Additional takeaways:

Trellis

- Leave ample room to the edge of the field for tractor turns. We somewhat underestimated the room on one edge, after accounting for the guy wire spacing.

- A tractor auger would have been preferable to the manual auger for drilling post holes. It was very labor intensive to drill the holes. We had initially intended to go down 4’ but stopped at 3’ given the amount of effort—and this was without even any real rock issues.

- We installed the ground anchors by hand (turning with a crowbar). Making an adaptor for a tractor augur would have been worth the effort.

- We purchased 7x19 strand cable as had other hopyards as described on the internet. It seems the trend has swung toward using 1x7 strand cable for greater rigidity and durability and is recommended.

- Angling the outside posts produces the strongest trellis. If the load (from the bines) on the cable along the row matches the tension in the guy wire, the resultant force can be directed straight down the angled post, rather than producing resultant sideloads.

- We overlooked using a low wire in the initial design but eventually added one. This is debatable but useful for tying off the twine at the bottom as well as keeping the drip irrigation out of the dirt (where it can get clogged). The alternative is attaching twine with w-clips, which are replaced annually.

- Trellis cable and hardware cost significantly more than the hopyard budgets of many online sources from only a few years ago due to steel price increases.

Plants

- Apply sufficient nitrogen (200 lbs./acre annually, spread throughout the season) but not more, or the sidearms will be vertically overseparated (reducing yield on the short trellis).

- Similarly ensure some water every 2-3 days (about 2 gallons per plant).

- First year plants are not worth the effort to harvest with yields about 10% of year 3.

- The Cascade hops variety seems to be ready to harvest by late August in southern Michigan. Have alpha acid analysis done, then harvest once the typical 6-7% mature content ("dried," i.e. with 10% moisture) of this cultivar is reached. You will need the AA content regardless in order to sell the product, since brewers need it to determine quantity in brewing.

- Our hopyard, situated in the corner of our field, seems to have more clay in the soil along the east and south edges (which the hops don't thrive in). This demands adding additional organic matter (potentially compost, gypsum, or peat moss).

- Downy mildew control is our biggest disease issue. Be sure to remove bines and spray after the harvest in fall.

- Weed control appears to be the biggest challenge going forward, at least while following organic practices.

- Experience showed that it is beneficial to choose your 2 - 3 shoots per bine close together, to have a single spot to weed around. We inadvertently cut a few shoots with the weed trimmer that came from different directions. This was heartbreaking late in the season when they were nicely developed shoots. We have also now learned that these 2 - 3 should be chosen early, and all others clipped to promote their growth.

Irrigation

- The pressure equalizing drip irrigation still favors running downhill to maintain sufficient pressure. We had to reverse the direction in our field in year 2 to improve flow.

Project Outcomes

A clear key to short-trellis hop yield is developing sidegrowth from a low height. Some of our plant sections displayed this better than others. We presume this to be chiefly a function of fertilization and irrigation rates and frequency. Understanding this would be worthy of study, as would be the suitability of other popular cultivar(s) for a low-trellis in addition to Cascade, such as Centennial.