Final report for FNC17-1086

Project Information

At least two local farmers have been working with the Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center (ML-ELC) to grow cane sorghum as a demonstration of old fashioned sorghum syrup production at the Learning Center. Cane sorghum previously was produced in Indiana as a "local sugar" in the late 1800s, but over the years production of this crop has nearly disappeared. As a small group of farmers, (4 cooperating farms in year 1), we plan to work together to focus on the challenges associated with profitably producing sorghum syrup on small plots in northern Indiana. The challenges are specifically: the appropriate seed variety/varieties for this area; optimal plot sizing to balance yield and labor inputs on a small farm; feasibility of cooperative cane pressing, juice evaporation and syrup processing; and development of new regional markets for this "local sugar" product. Our farmers will work on small (1/4 - 1.0 acre) plots, tracking planting, cultivation, harvest, and processing costs, yields for various seed varieties, and marketing efforts, and will share our results with other local farmers through field days, open meetings, farm conference presentations, blogs, and electronic media releases.

This project attempts to reintroduce sweet sorghum as a profitable crop for small scale farms in northern Indiana. Our challenges include: 1) determining the optimal variety(ies) of sweet sorghum for production in northern Indiana climate; 2) developing a cooperative approach to planting, cultivating, harvesting, syrup production to increase profitability on small plots and to improve the quality of life for the farmer, as cultivation and harvest/processing can be very labor-intensive; 3) reintroducing sweet sorghum to local markets such as farmers markets, restaurants and breweries; and 4) sharing knowledge with other small farmers so that this "local sugar" product is not lost to future generations. Over two years, four small farming operations attempt to meet these challenges in order to reintroduce sweet sorghum to a new generation of producers and consumers in our region, who are mostly unfamiliar with this value-added product.

This project attempts to reintroduce sweet sorghum as a profitable crop for small scale farms in northern Indiana. Our challenges include: 1) determining the optimal variety(ies) of sweet sorghum for production in northern Indiana climate; 2) developing a cooperative approach to planting, cultivating, harvesting, syrup production to increase profitability on small plots and to improve the quality of life for the farmer, as cultivation and harvest/processing can be very labor-intensive; 3) reintroducing sweet sorghum to local markets such as farmers markets, restaurants and breweries; and 4) sharing knowledge with other small farmers so that this "local sugar" product is not lost to future generations. Over two years, four small farming operations attempt to meet these challenges in order to reintroduce sweet sorghum to a new generation of producers and consumers in our region, who are mostly unfamiliar with this value-added product.

Meeting the challenges

Crop variety: To determine the best seed variety for our region, we consulted with the National Sweet Sorghum Producers and Processors Association (NSSPPA) and trialed several seed varieties (Dale, Sand Mountain, 1810, 2308, and a dual sugar/popping variety) in Year 1 on plots small enough for one farm family to handle efficiently. The plots ranged in size from 1/4 to 1 acre. We tracked timing for planting, intensive cultivation, scouting, plant growth, harvest, pressing, evaporation and finishing the product and made adjustments in our plans for Year 2.

Our varieties all grew well in the region. We concluded the dual sugar/popping variety produced a substandard syrup and will not trial that variety again. We had a problem with stem lodging on the Sand Mountain variety on three of the plots, even though the plots were mostly protected and high winds were generally not a problem during the growing season. We determined that this stem lodging likely resulted from high fertility of the soil and close plant spacing, which produced heavy vertical growth of tall, thin stalks; we will plant a shorter variety in Year 2 and thin plants to 12" spacing in an effort to increase stalk size and strength.

On three sites, the seeds were in the ground the first week of June. On the Palmer farm, wet conditions caused late planting (approximately July 1), and although the varieties used (1810 and 2308) had shorter maturity dates, harvest was delayed until mid-October and much of the cane was not pressed due to time and weather constraints. Palmer farm used a corn binder but had difficulty with tall grass (foxtail) clogging up the cutter. It still required several persons to gather and stack the cane and cut off the seedheads.

Consultation with a regional grower and processor indicated problems with the Dale variety as well, and this producer recommended Sugar Drip as a variety that has been successful in northern Indiana.

Year 2: 2018 season. We purchased the variety Honey Drip and planted it on 3 farms in plots totaling just less than 1 acre. This variety seemed to have no problem with lodging. Honey Drip is a 105 day variety and our goal was to have it ready to harvest at the end of September. The Palmer farm did not plant sorghum in year 2, but we added another farmer-partner, Filler Family Farm, to the group. The entire crop was harvested, stacked and ready for processing by September 28. Some was gathered into shocks in the field and stored for several days in that manner.

Year 3 (2019 season): We again planted Honey Drip variety, at a much lower rate by utilizing a custom made planter plate specifically made for this seed, which greatly reduced the multiple seed-drop that had been troubling us the past two years. Total planting on the Wise, Loomis, and Filler farms combined to slightly more than 1 acre. Expectations are that we will be able to harvest at least the same amount of cane as in year 2, and produce slightly more syrup.

Tools and equipment for planting and harvest: In Year 1, we used two different planters to help identify best seeding patterns to help reduce labor for cultivation during mid-summer, which is crucial for a profitable crop. Both pieces of equipment tended to release too many seeds per row resulting in the need to thin plants (optimal plant spacing is 5"-12" between plants). Space between rows varied from 30" to 36". We employed hand-thinning of rows and mechanical cultivation between the rows, and hand cutting vs. modified corn-bailing equipment for cane harvest. The agricultural intern and farm workers from ML-ELC and Old Loon Farm assisted with harvest at the Palmer Farm plots, which were larger in size. Organic cereal rye was sown as a cover crop on the plots after harvest.

To make improvements in Year 2, we planned to adjust the planting equipment and seed plates for better in-row seed spacing, and our Amish farmer consultant suggested using tapioca (as a dummy seed) mixed with the sorghum seed to promote spacing. We plan to thin plants very early in the growth process to 8" - 12". Spacing between rows will depend on the cultivation equipment each farmer chooses to use, some of which is shared cooperatively, at 30"-36". Plot size is dependent on the farmer's preferred use of equipment, available land, and labor available at critical cultivation and harvesting periods. We found that overall in Year 1, the intense time and labor associated with harvest, pressing, evaporation and finishing would severely limited our capacity for any increase in production of the syrup in Year 2. This became another challenge for our project.

Year 2 planting was completed in early June with the same 30" row planter for all plots. The planter was transported to each farm as soon as the ground was ready, and was completed in two days. Since we had trouble in year 1 with multiple seed drops with our planter, we cut the seed with pearl tapioca. Although not as problematic as in year 1, we still had to spend a significant amount of time and labor to thin plants in the rows to give the stalks room to grow to the desired girth. Early thinning in June was easier and more effective than later (July-August) thinning. Daikon radish - crimson clover mix was used as a cover crop on the plots post-harvest.

We tried several new techniques for harvest in year two, including a power cutter fabricated from a weed-wacker frame utilizing a saw blade. We also bundled the cane, used a chainsaw to cut the seed head off, and shocked cane in the field for drying rather than piling it into covered storage sheds until it could be transported for processing. Farmers agreed that the cutter was not as efficient as they had hoped, still requiring hand-gathering the stalks which fall in every direction. Stacking the cane in the field on wooden cradles made cutting the seed heads with a chainsaw easier, but was time consuming and probably not worth the effort. Plans for next harvest year include procuring a corn binder with an elevator to cut and bind the cane and place it directly onto the trailer used to transport it to the processor.

We tried several new techniques for harvest in year two, including a power cutter fabricated from a weed-wacker frame utilizing a saw blade. We also bundled the cane, used a chainsaw to cut the seed head off, and shocked cane in the field for drying rather than piling it into covered storage sheds until it could be transported for processing. Farmers agreed that the cutter was not as efficient as they had hoped, still requiring hand-gathering the stalks which fall in every direction. Stacking the cane in the field on wooden cradles made cutting the seed heads with a chainsaw easier, but was time consuming and probably not worth the effort. Plans for next harvest year include procuring a corn binder with an elevator to cut and bind the cane and place it directly onto the trailer used to transport it to the processor.

Year 3 planting was completed in early June with the 30" row planter utilizing a custom-made seed plate for the honey drip seed. No tapioca was used. Requirement for thinning between plants was much reduced and was completed as much as possible by early July. Cultivating and/or tilling between rows during the first two months helped to control weeds, although the very wet spring and summer kept the soil wet far into July. Growth seems to be uneven due to wet conditions, which have also affected corn, soybeans and vegetables in this area.

Year 3 planting was completed in early June with the 30" row planter utilizing a custom-made seed plate for the honey drip seed. No tapioca was used. Requirement for thinning between plants was much reduced and was completed as much as possible by early July. Cultivating and/or tilling between rows during the first two months helped to control weeds, although the very wet spring and summer kept the soil wet far into July. Growth seems to be uneven due to wet conditions, which have also affected corn, soybeans and vegetables in this area.

Tools and equipment for pressing, evaporation and finishing: In Year 1, as planned, we used cooperative labor and tools to process the sorghum cane into syrup. We pressed all the cane with Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center's (ML-ELC) antique press powered by an antique tractor. We also evaporated the juice to at least 220o at ML-ELC on their wood-fired evaporation unit. We were able to store the cooled, partially processed juice in plastic 5-gallon buckets at ML-ELC's walk-in cooler and use the ML-ELC produce facility to store and clean equipment for pressing and evaporation of the juice.

Due to the extended time frame for harvesting, we had an equally extended time frame for finishing and canning the final syrup product, which made the one-time rental of a commercial kitchen for finishing and canning unworkable. Therefore final finishing and bottling of the syrup was completed by Jane and Charlie Loomis at Old Loon Farm's kitchen facility over a period of several weeks between October 8 -31. We initially boiled the syrup product to 235o (Brix reading of ~78) outdoors over propane cookers, and then completed the final filtering and bottling on the stove top indoors. We used finishing equipment that is also used for maple syrup and/or honey production, including filters, refractometer, thermometers, and stainless steel pots. The total process took most of the month of October and produced an uneven product.

Data collection and information-sharing: We gathered information from regional producers and two of our partners attended sorghum festivals in Kentucky and Tennessee in late summer 2017. Problems with aphids and fungus are affecting crops in the southern US, but we have not had those problems with our crop in northern Indiana so far. We tracked seed varieties and soil types, as well as harvest and syrup production outcomes over the two plus growing seasons.

In early 2019 one partner-farmer registered for and attended the NSSPPA convention in Pigeon Forge, TN. The programming focus was beginning sorghum farming and he brought back more significant information to the group. He also submitted a jar of our 2018 product to the sorghum syrup competition which ranked in the top 50 submissions, and reported that we had the most "professional looking" label.

In Year 1, we shared information about our project with other local farmers through electronic media, handouts, farmer meetings, cooperative crop scouting, and a local sorghum festival held at the ML-ELC in mid-October. This effort generated interest and recruited one additional farmer to work with us in Year 2 of the project. Through meetings and mentoring, we helped the new producer select seed, plant, cultivate and harvest based on our findings from Year 1 of the project.

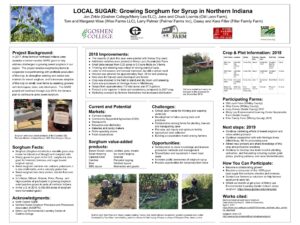

In March 2018, we shared our experience and network with other farmers at the Indiana Small Farms Conference (March 1-3) through general networking as well as a poster presentation by the agro-intern about our project. Our proposal to present our project at the 2019 Indiana Small Farms Conference was not accepted, but the cooperating farmers utilized another poster presentation (see photo at left) which included free samples of the syrup and value added products, and was very well received. Contacts from this presentation were followed up with our sales person in the spring and summer.

In March 2018, we shared our experience and network with other farmers at the Indiana Small Farms Conference (March 1-3) through general networking as well as a poster presentation by the agro-intern about our project. Our proposal to present our project at the 2019 Indiana Small Farms Conference was not accepted, but the cooperating farmers utilized another poster presentation (see photo at left) which included free samples of the syrup and value added products, and was very well received. Contacts from this presentation were followed up with our sales person in the spring and summer.

Marketing the Sweet Sorghum Syrup: Our goal is to produce a superior syrup that is standardized across the cooperating farms, and to market it regionally at farmers markets, restaurants and breweries. We commissioned a graphic artist to design a label that would promote a single product name but allow individual farmers to market themselves as well. This resulted in the Indiana Natural label that has space to identify the individual farmer's contact information. The labels are designed for Avery weather-resistant shipping labels, and can be printed in any quantity at our local print store at a much more reasonable price than ordering large quantities of pre-printed labels. Our research indicated that we were not required to include nutritional information on the label, so for this year, we employed a very simple label format.

After unsuccessfully searching for an appropriate marketing coordinator over the first 6 months of the project and nearing the deadline for our first event, we contracted with a local writer to help us produce press releases, hand outs, and on-line event announcements to work with us for our 2017 fall festival. For marketing our sorghum syrup, we realized that each cooperating farmer had many local business contacts in the region, and that we could continue to contact local outlets and distribute product and price information over the fall and winter season. Through 2018, we had not hired a professional marketing coordinator, but we sold our sorghum syrup at local farm markets, and distributed product and a pricing sheet to local chefs and restaurants, food businesses and brewers, requesting they sample our product and give us feedback. This effort to expand the market continued throughout Year 2, with hiring of a marketing coordinator remaining an option.

Beginning in April, 2019 we hired a part-time salesperson to visit local markets and investigate inclusion of our product in Indiana markets and fairs. Since our product is grown and produced in Indiana, we are also utilizing the Indiana Grown label on our product label.

Our marketing efforts in 2018-19 included introductory and sales trips by our salesperson and partner-farmers to various locations across our region, including several breweries and brew clubs, at least one distillery, one cider mill, quite a few restaurants and caterers, several specialty retail outlets, several farmers markets/ holiday bazaars, and a couple of "foodie" organizations. We participated in workshops; we distributed promotional information about sorghum, as well as complimentary jars of the product and business cards, at these locations. There seems to be a strong interest in the product as many people remember their grandparents or parents using the syrup, but do not see it locally available in stores. Sales at farmers markets have been reasonable; we have interest in bulk product from a distiller who is interested in making "local" rum. Through 2018 and 2019 we piloted marketing value-added products, including sorghum caramel corn (quite popular), sorghum cookies, sorghum cake, and sorghum peanut brittle. We are also experimenting with a sorghum based BBQ sauce, and are planning to age some of our 2019 product in whiskey barrels to produce another profitable, value added product.

Our biggest challenge in Year 1 was the time and labor crunch surrounding harvest and processing of the syrup. The Merry Lea equipment proved to be great for an educational demonstration, but the ML-ELC is not appropriate for the long term or for bulk pressing and evaporation over a sustained period. We learned a great deal about timing and the limits of our production capacity based on the critical harvest and syrup processing window, and realized that farmers would soon abandon sweet sorghum production unless the process could be streamlined. Therefore we began searching for alternatives to producing the syrup "at home."

We located an Amish farmer in Middlebury, Indiana, who operates a finishing plant (Heritage Acres) for cane sorghum. This operation is not unlike the major producers in the southern US, or for that matter, historical production in our area where farmers took their cane to a central processing site to be made into syrup. The facility uses a steam evaporation/cooking process and bottles the finished syrup onsite. Choosing to have our cane processed at this facility would require us to harvest our cane during a specific, short window of time around the end of September, and to haul the harvested cane on trailers approximately 36 miles one way. The facility would chop, press, evaporate and bottle our syrup at a price that would have to be covered by our wholesale and retail sales. We could still market our product under our own cooperative label.

Utilizing the finishing operation facility would solve several problems that we encountered in Year 1: 1) It would allow us to utilize the ML-ELC for use as a demonstration/educational festival site without overtaxing the staff or making major improvements to their existing facilities; 2) It would significantly decrease the labor commitment required of the individual farmers in the finishing and bottling process, allowing us to increase production and output of the syrup product, as long as we could handle the labor required for growing and harvesting; 3) it would standardize our product. These are major issues that directly affect our quality of life.

Utilizing the finishing operation facility would also affect our scheduling on the planting side: 1) we would need to standardize the seed variety(ies) so that we produced a uniform crop that could be planted early enough to ensure harvest by late September, and one that would resist lodging, increasing our yield; 2) we would need to coordinate our cooperative labor to harvest, pack and transport our cane to the processing plant at the appropriate time; 3) we would need to determine the appropriate plot size, crop yield, and market price of the syrup to profitably cover the cost of processing; 4) we would need to save enough harvested cane to provide material for the educational demonstration/outreach event at Merry Lea ELC in October, as well as have syrup product for tasting and sale at the festival.

We have learned over the course of the project so far, that central processing is a common way that sorghum is and has historically been produced. Individual processing is possible and sustainable for a small amount of syrup production, but fails to support production of larger quantities for retail or wholesale. The cooperating farmers agreed that central processing with Heritage Acres would be an appropriate change for Year 2 for our project.

We found at least two additional farmers interested in production of sorghum syrup for the 2018 season, with one following through and joining the cooperative effort. We planned to support their inclusion in the group by: 1) information sharing, physical assistance in growing, cultivating and harvesting the crop; 2) providing seed for crop and cover crops; 3) sharing planting, cultivating and harvesting equipment; 4) providing individualized labels for their syrup product. In return, the new farmer is to 1) assist with group planting, cultivation and harvest; 2) share agronomic information regarding their plots; 3) assist with marketing and promotion of the syrup product; 4) assist with outreach events.

Extension of Project to Year 3: In November of 2018 we asked to have the project extended into the 2019 growing season. This afforded us a third planting and growing season, as well as extended our time for public outreach and marketing.

Year 2 (2018 season) incorporated several changes. Changes to the planting and processing resulted in a better harvest, and a more palatable and consistent syrup product, with output increase from approximately 20 gallons to 97.5 gallons.

We again supported the field day/sorghum syrup demonstrations at the Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center but held a separate outreach educational event for interested farmer/growers and potential markets. The luncheon meeting was held in Goshen, IN at Anna's Bread restaurant near the Goshen Farmers Market, featured our Amish producer/processor as the main presenter, and drew 16 interested potential growers/consumers, a local newspaper columnist, and potential markets. As in the 2017 farmer's meeting, we used this opportunity to highlight foods made with sorghum syrup as well as to distribute our product to restaurants, breweries and coffee houses in the area.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Educator)

- (Researcher)

- (Educator)

- (Researcher)

Research

Our 2-year plan was to plant small plots of sweet sorghum that could be managed by one or more farmers using shared planting, cultivating and harvesting equipment, to press the cane and evaporate the juice on antique equipment at the Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center (ML-ELC) of Goshen College located at Wolf Lake, Indiana, and then to finish and bottle the syrup at a central location such as a rented commercial kitchen. We proposed that these small plots could be managed in a sustainable manner by small farmers interested in a value-added product that could be sold locally at farmers markets and used by local chefs and brewers.

To the extent possible, we planned to use equipment and tools that are often used for maple syrup and honey production, often owned by small farmers but not in use during fall harvest and processing of sorghum. Small plots also support the utility of smaller hand and mechanical gardening tools rather than large farm equipment.

We trialed several varieties of sweet sorghum seed in year one, including Dale, Sand Mountain from Seed Savers, a dual pressing/popping variety, as well as 1810 and 2308 varieties from Townsend Sorghum Mill in Kentucky. We also used some saved seed from the 2016 season, primarily Sand Mountain.

Year 1 included planting, harvesting and syrup production, as well as research into sorghum syrup production regionally and in the southern US. We hired a student intern to help with collection of agronomic data. We shared information with other local farmers through a harvest festival and demonstration, electronic and print media, and networking/presentations at the Indiana Small Farms Conference in March. We planned to recruit additional farmers and/or rent additional acres on which to produce sorghum for Year 2 of the project.

By collecting agronomic information on this project and sharing our experience and results with other local farmers, we hoped to increase the production of sweet sorghum syrup, a "local sugar" product, in our area, thus adding another value-added product that small local farms can produce and share with their communities.

By Year 2, we had settled on Honey Drip seed, and abandoned the antique press and evaporation equipment due to time and labor commitments, time conflicts with Merry Lea's educational programs, and quality of the finished syrup product. We contracted with a state-inspected local processing facility to press, evaporate and bottle the cane syrup. This required transporting our harvested cane approximately 72 miles round trip to Middlebury, IN, and returning to pick up the processed syrup, but was well within the time and economic margins of the product.

By Year 2, we had settled on Honey Drip seed, and abandoned the antique press and evaporation equipment due to time and labor commitments, time conflicts with Merry Lea's educational programs, and quality of the finished syrup product. We contracted with a state-inspected local processing facility to press, evaporate and bottle the cane syrup. This required transporting our harvested cane approximately 72 miles round trip to Middlebury, IN, and returning to pick up the processed syrup, but was well within the time and economic margins of the product.

We had also revised our tools, still sharing equipment but using fewer hand tools and more small tractor-driven tools due to the time and labor commitment. We started using machetes, knives and hedge trimmers to cut cane and top the seed heads, then tried mechanical cutters and chain saws, and have determined that mechanized tools, including rototillers and small tractor-pulled cultivator for weed control, chain saw for cutting off seed heads, and a corn binder with elevator for harvesting are necessary to be efficient. Sharing these pieces of equipment among several cooperating farms is affordable and works well.

In Year 1, we collected growth and yield data for the various plots (4 separate farms) and seed varieties. Cane harvest, pressing and juice evaporation, finishing and bottling of syrup presented us with several problems that we attempted to solve during Year 2. Chief among these problems: planting in wet, cool weather; stem lodging of the sorghum crop; labor for cultivation and harvesting; and labor for processing syrup.

In Years 2 and 3 planted Honey Drip (105 days) seed variety on all the cooperating farmers' plots on June 6-10 and harvested across a week in late September in order to haul the entire cane harvest to the processor at one time. Attention to thinning and tilling between rows to control weeds resulted in a greater harvest: on Old Loon Farm, cane weight in 2017 was 600 lbs; the same plot size yielded 900 lbs in 2018. Wet and cool spring weather has been a challenge in all years, but we have been able to get the seed in the ground by early June. 2019 has been especially wet and the crop in the field is uneven in height. We had no problems with lodging in 2018, but one farmer has had some problems in 2019. Areas with muck soils (2 farms) are especially prone to weather related issues such as uneven growth and lodging.

Initial sharing of our information and networking with other farmers took place during our October sorghum festival at the Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center, Wolf Lake, Indiana, and continued at the 2018 Small Farms Conference in Danville, Indiana in March. The following year we supported both the Merry Lea ELC fall festival and sorghum demonstration and held a separate outreach luncheon in Goshen with Urie Miller, our processor, as presenter. We networked at the 2018 Small Farms Conference and our intern presented a poster on the first year's outcomes. In 2019, we farmers presented a second poster session at the conference which was well attended and yielded some great contacts for further marketing.

Production of syrup in year 1 was less than 20 gallons and the product was quite dark in color and inconsistent in quality. Production of syrup for year 2 was 97.5 gallons and the product was amber-colored, tasty and consistent across the total batch. Cost of processing included glass jars, packing boxes and total processing, and was well within margins that would still yield a profit at market prices

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Our cooperating farmers consulted with local extension agents Steve Engleking, LaGrange County and Roy Ballard (Hancock County), regarding nutritional labeling, food-link listing and potential presenter contacts. We visited two sorghum festivals, Muddy Pond in Tennessee and Liberty County in Kentucky, and the NSSPPA national convention in TN. In Kentucky, we consulted with Danny Townsend of Townsend Sorghum Farms regarding seed varieties, harvesting, pressing and evaporation. We consulted by phone with a farmer who is part of a sorghum cooperative in Missouri, and who reached out to us after reading about our project on the SARE website. Locally, we visited Urie Miller, an Amish farmer who runs a sorghum pressing and processing operation (Heritage Acres) in Middlebury, Indiana, in order to evaluate his operation, consult on seed varieties, plant and harvest dates, and compare the economics of having our crop processed and packaged by his company instead of processing on-farm. Mr. Miller also presented his story and experiences with sorghum production at our 2018 farmers luncheon event.

Several publications were produced in Year 1: We produced an advertisement flyer for the festival which was also distributed electronically via mail lists and FaceBook, Festival-flyer-2017 , two handouts for our festival event, sorghum fact sheet Sorghum-Fact-sheet and sorghum syrup process sorghum-process. In Year 2 we produced a poster for the Indiana Small Farms Conference, and updated it for the 2019 conference.

We created a marketing sheet to distribute with our sample product to local restaurants, food businesses, chefs and brewers. We also used this publication as an information sheet at our farm booths at local farmers markets. Indiana-Natural-Pricing-sheet

On October 11 and 12, 2017, we held an on-farm festival at the Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center, which included a free, open to the public supper featuring foods made with sorghum syrup, an overview presentation of our SARE project, and a farmer-panel discussion about our SARE project on Thursday evening. On Friday we demonstrated cane pressing, evaporation and syrup finishing at the festival, welcoming visitors with free tastings of sorghum syrup, biscuits and sorghum cookies. Our outreach recruited two, possibly three additional farmers who wish to plant sorghum for year 2.

We produced pre-and post-event press releases, Sorghum-PR-1 and Festival-PR-EO-final. These were sent to local print and electronic media outlets and were distributed via FaceBook and Goshen College. These covered announcement and reporting on our October 11-12 sorghum festival, held at Merry Lea Environmental Learning Center. We also created the event and collected RSVPs through EventBrite.

On October 30, our farmers luncheon meeting was held at Anna's Bread in Goshen. Sorghum was highlighted in the Old Loon Farm blog in October and November, 2017, as well as April and October, 2018, and May, 2019.

Learning Outcomes

Lesson 1. Sorghum can be grown successfully on small plots in northern Indiana but labor is the key factor in profitability. We reduced our labor commitment by improving our tools: Using the proper planter seed plate; using a cultivator that can be pulled by tractor rather than hand-weeding or walk-behind rototiller; using a corn binder and elevator instead of hand-cutting and collecting cane.

Lesson 2. Cooperative farming saves money for small plots. All the above tools can be utilized by a group of farmers successfully, as small plots take minimal time and effort to plant, cultivate and harvest if the proper equipment is available and is shared.

Lesson 3. While processing of the cane into syrup can be done at home, it is much more efficient and quality is standardized by utilizing a commercial processing plant. The trade-off in cost vs. quality of life is acceptable, especially when a cooperative group of farmers shares the cost.

Lesson 4. Sorghum is a local sugar that cannot compete in price with white sugar. However, as a natural and local product that has a long shelf life and is high in nutrition and flavor, it has a niche market that can be exploited for profit by small farmers in their local community.

Lesson 5. Since sorghum syrup is not widely available or known, there is a strong market potential for the product, especially in local farm markets, health food stores, and specialty markets. Brewers and distillers are interested but we have not yet seen a strong interest in large quantity production.

Lesson 6. It is next to impossible to attract a speaker/presenter to a small gathering of farmers, especially during the late summer/fall season.

Project Outcomes

We were actually surprised by the number of local and regional people who approached us and related stories about how sorghum was used in their families when they were young, or how they grew sorghum as a crop in past years. Many were anxious to purchase a jar of syrup.

We also were called by a farmer from Missouri who read about our project on the SARE website and was representing a small cooperative sorghum group, inquiring about pests and other crop issues and wondering how we were dealing with the problems in our area. They had lost a year's crop to aphids, which haven't been a problem yet in northern Indiana.

And finally, we received an email from a national agricultural worker in Ethiopia who also found our project on the internet, who requested more information about our processing plant. We were able to refer him to the NSSPPA and the experts there. It's interesting that sorghum as a crop came to America from Africa, and is now being re-examined in Africa.

We felt that we were able to solve many of the challenges we faced on the agricultural side. However, keeping in mind our focus on profitability for small farmers producing sorghum syrup on a small scale, we constantly had to pull back from visions of marketing this product on a large scale -- i.e. to large breweries, restaurant chains, distilleries, etc. Cooperatives could produce enough syrup to meet these requirements, but that was not the focus of our project.

There certainly could be interest in follow up research on the marketing aspect of this natural syrup product, but at this point we as a cooperative group are not planning to pursue that further at this time. This product has great potential but suffers from lack of recognition. We would suggest that the public could be made more aware of sorghum syrup and its nutrients and availability if it were included in the specialty crops category and identified through the FOOD-LINK information program.