Final report for FNC17-1104

Project Type: Farmer/Rancher

Funds awarded in 2017: $14,305.00

Projected End Date: 12/31/2018

Grant Recipient:

Larryville Worm

Region: North Central

State: Kansas

Project Coordinator:

Nicholas Ward

Queen Alidore LLC

Project Information

Description of operation:

The operation consists of a starting stock of 110lbs of Red Wiggler Composting worms. These worms are split between 3 beds and each bed has three compartments. In each of these beds the worms will be fed in 2-month periods after which they will be lured (by food) into performing horizontal migration (moving from the first into the second of the three compartments in each bed.) This migration is conducted so that the worms leave their bed of castings and harvesting is made much easier. Partnerships have been formed with area schools and one area grocery store to provide food waste feedstock to the worms. In the spring Lawrence Worm Farm will begin to shift focus from growing the worm stock to marketing the worm castings and worms.

Summary:

The project is one of social entrepreneurship, focusing on utilizing the latent energy available in foodwaste and to transform that energy into a nutrient rich soil amendment (natural fertilizer) via Red Wiggler composting worms. Ideally the project would influence policy within the municipality of Lawrence, KS by paving the way for composting of food waste by the city/county.

Problem

Within our current system, food waste is an endemic problem. Recognizing the latent potential in what is often cited as 41% of overall generated waste, there are a number of ways to reclaim and put this latent resource back into a sustainable energy cycle. Left to current methods, food waste is a staunch contributor to global warming, creating methane gas as a bi-product of its putrefaction in the non-aerobic environment that is our common landfill. In addition, this great mass of waste (41% overall) also requires regular transportation, causing more use of fossil fuels in an effort to remove the resource from its community of potential use.

Solution

One solution to the above stated problem is to keep food waste where it is created. This can be achieved by implementing a method of upcycling via the materials latent potential. Through vermicomposting practices the once discarded and costly food waste becomes an abundant resource for generating the nutrient rich soil amendment known as worm castings. By shifting the current paradigm, we tap into a new market for food waste

reclamation that is sustainable and cyclical in its use as a resource.

Within the 23 month grant period our goal is to take the 200lbs of worm livestock afforded through this grant and to grow that stock to 1000lbs. Doing so would allow us to accommodate the processing of 500lbs of food waste per day resulting in a yield of roughly 5,000lbs of worm castings per month. This intentional slow-growth model will allow for the identification of best practices, reliable community partners and applicable markets.

Through the test plot component of this grant we will have clear evidence and an example of the benefits of worm castings in a controlled growth environment. These results will be used for educational purposes and for marketing of the worm castings. The grand hope beyond the grant cycle is that this specific approach to food waste mitigation become part of the county’s food policy plan mirroring in scale that of our current recycling

program. As a grand bonus, the community would be flush with rich soil and an extended life for our city dump. This venture seeks to be both economically and ethically sustainable in approach, practice and outcomes.

Summary:

Through the Larryville Worm SARE Farmer Rancher grant and numerous Kansas Green Schools grants the initial objectives of disseminating food waste education, forming institutional partnerships, and on-site mitigation of food waste were achieved. The scale at which each of these were achieved in relation to the initial goal varied.

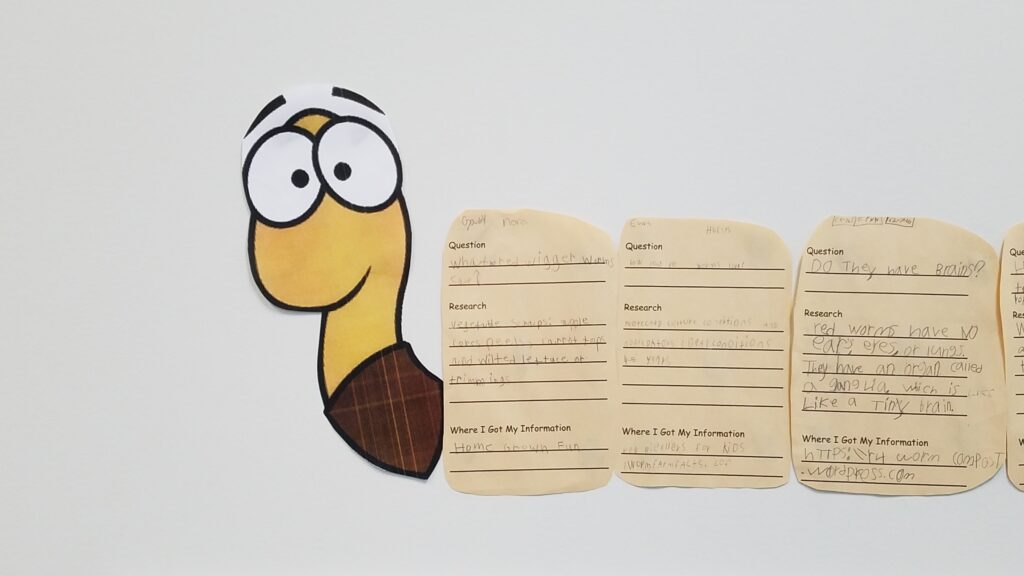

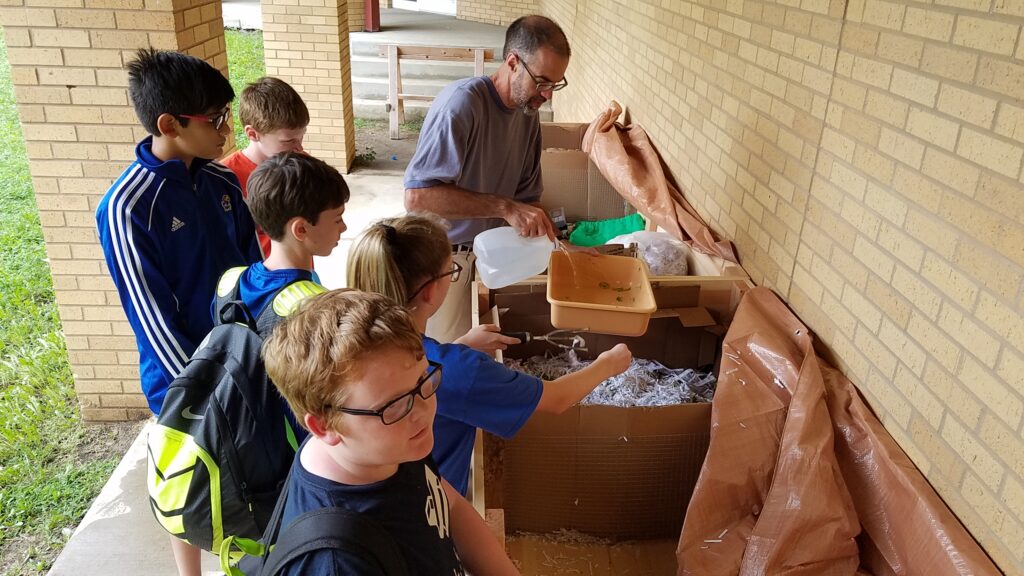

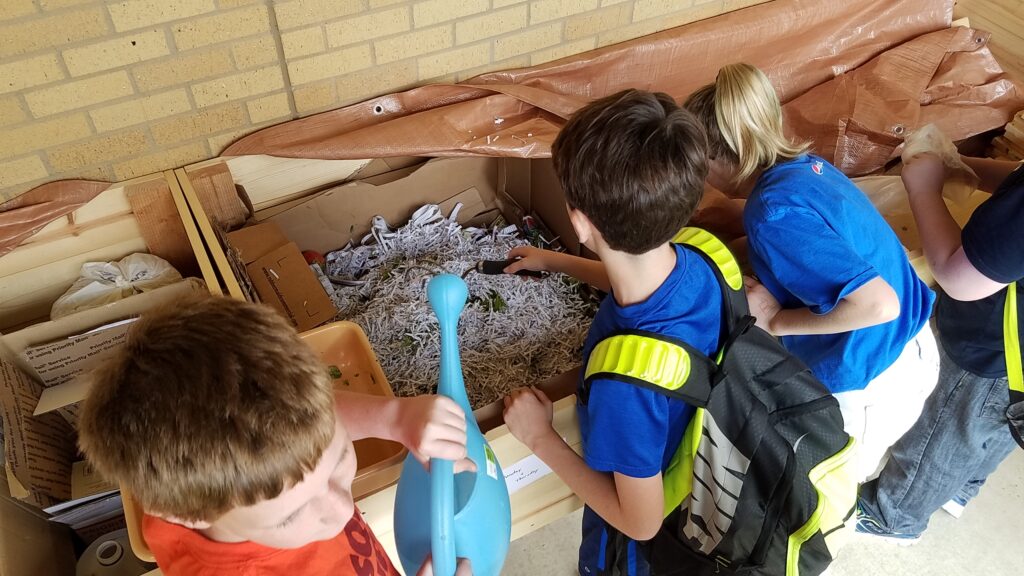

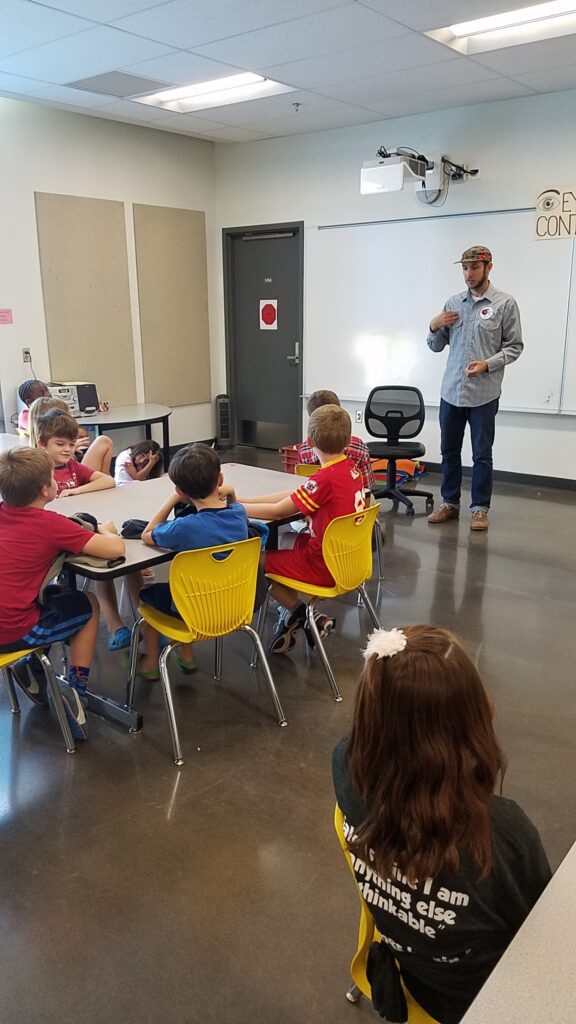

1.) Youth Education was by far the most successful component. 3,844 Lawrence youths ranging from 6-18yrs of age took part in assemblies, workshops, hands-on food waste audits and various projects dealing with composting, vermicomposting and food waste. Youths took to the subject matter quickly and became very engaged with the composting process and were empowered through their role in mitigating the food waste.

2. Partnerships were formed between Larryville Worm Farm, Sunrise Project, 6 area schools, and 1 local grocer (Checkers Foods.) Each of the six schools participated actively by allowing the introduction of workshops, field trips and school-wide waste audits which served to educate students on issues of food waste. 5 of the 6 schools received worm bins both large and small scale and through collaboration between administration, students, teachers, custodial staff and lunchroom staff established in-school composting by adapting the lunchroom waste system. In each of these schools I was able to work with staff to transition from lunchroom "trash" bins to a series of bins for "recycling", "compost", and "landfill." With the introduction of these bins and the simple change in name from "trash" to "landfill" students were able to envision the outcome and the future of their waste products. Partnerships with the schools provided many opportunities. I worked with AP science students at Free State High School on issues of anaerobic composting and the future of urban food waste and I worked with kindergarten students on picture worksheets to identify which lunchroom foods could be fed to worms and which could not. It was a very rewarding 2 years of time spent in these area schools. My larger goal was to take these positive experiences along with information from our food waste audits including the 8,100lbs of food that was diverted from the local landfill through these projects and to convince the school district to adopt food waste mitigation via vermiculture as a viable option for lessening tipping fees at the local landfill and for becoming a more "green" and environmentally responsible school district. With the Green Schools grants coming to an end in 2018 and without additional funding, my work with the schools ended in May of 2018. There was no identified source of funding to continue this work. That being said I continue to work pro-bono with 1 school that has remained vigilant and decided to prioritize composting. Southwest Middle School now has 2 large worm bins in operation and will be adding a 3rd in the fall. Perry Kenard and Kristy Kopp (teachers) have been amazing partners and they've remained dedicated to continuing the work. I support their efforts through annual workshops, info sessions and a harvesting day.

3.) The Rancher component of this project proved to be very challenging. In our climate the composting worms have a number of adversaries. Red mites and soldier fly larva are two of the biggest issues. Summer heat and winter temps are the other two big issues. In both 2017 and 2018 my worms were plagued by red mites which decimated the worm populations in several beds within a very short window of time. Once I had removed the majority of the mites I ordered a new batch of worms and began another site so as not to contaminate. It took me the remainder of the year to rebuild the population and in the winter my heating system was compromised (electrically shorted by a mouse) and nearly half of my rebuilt population froze. In the spring the mites returned and further reduced the number of worms. At this point, with the grant funds exhausted and with word that the school district was not interested in participating once the Green Schools grants ended I recognized that while I had learned much in the process and much good was done through the mitigation of food waste and the youth education, the worm farm was out of steam.

If I was able to redo the project I would have kept the worms underground (cellar or basement.) I believe this would have solved the issue of the red mites as well issues of heating and cooling. If this could be done and if I was able to convince the school district to fund the project by the amount they were saving in tipping fees and to provide a 1 yr test stipend for a staff position I believe that the resulting evidence and benefits of the project would have led to a sustainable model of food waste mitigation for the entire school district.

Project Objectives:

The project objectives remain consistent. (at least at this mid-way point in the project.)

- Keep food waste where it is created. Through vermicomposting practices, once discarded and costly food waste becomes an abundant resource for generating the nutrient rich soil amendment known as worm castings.

- Scale up. Grow 200lbs of worm livestock to 1000lbs in order to scale up and accommodate the processing of 500lbs of food waste per day resulting in a yield of roughly 5,000lbs of worm castings per month. This intentional slow-growth model will allow for the identification of best practices, reliable community partners and applicable markets.

- Moving this project from a purely educational model to one that also provides sustainable revenue. A test plot will be constructed to inform growing methods as to the best possible worm casting content for different crops. The harvest of the test plots will yield an economic benefit for Lawrence Organics.

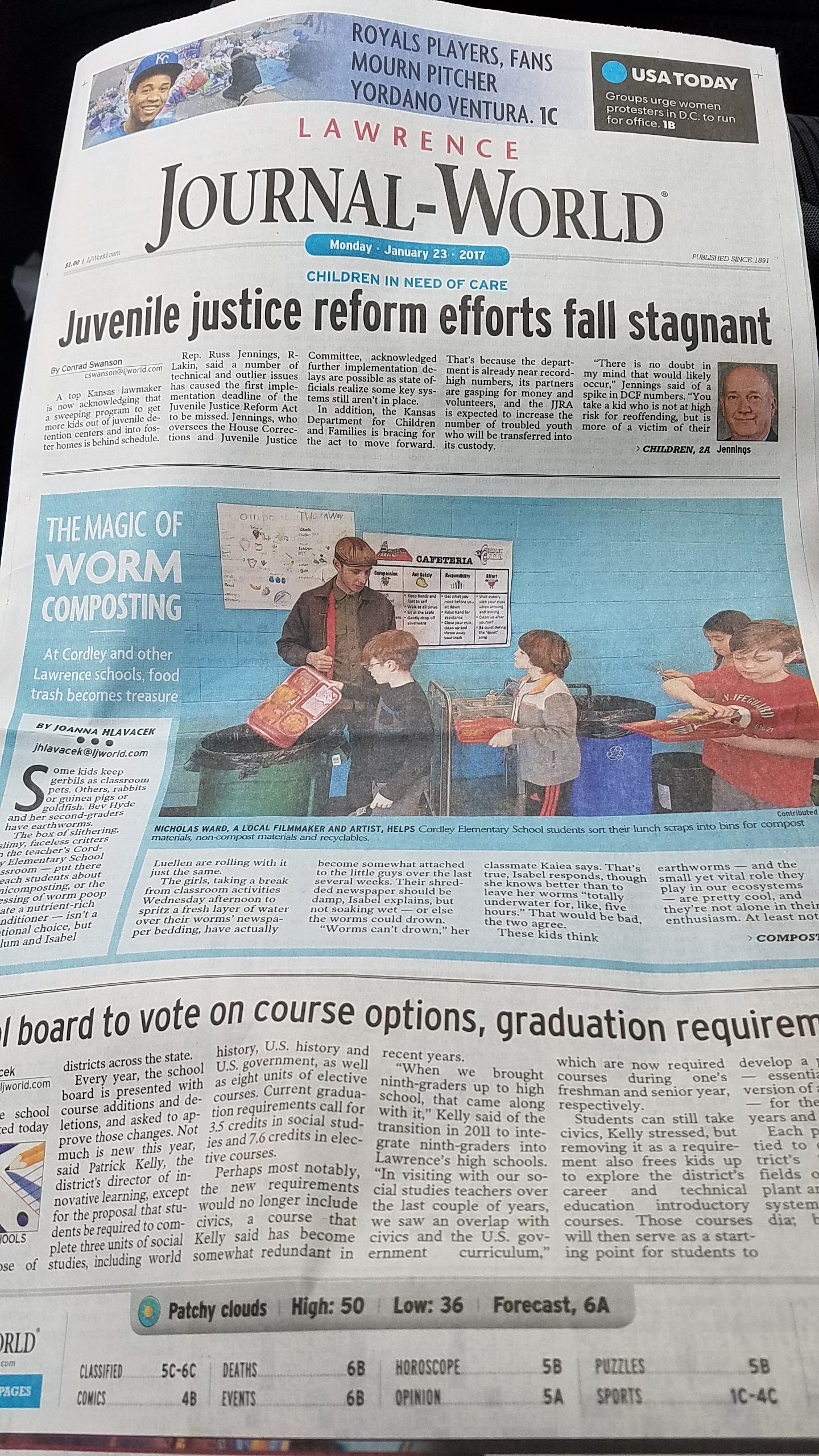

- Outreach will happen at Lawrence area schools and through the Sunrise Project greenhouse site. There will also be outreach conducted via local news media and social media including Facebook, Instagram, Lawrence Journal World, and Channel 6 News. The Lawrence Worm Farm website will be created to serve as a hub for information on the project and as a general source for information with specific focus on Lawrence Worm Farm products and the results (video and photo) of the test plot grown by Lawrence Organics. A full color, Tri-fold pamphlet will be created for distribution via the Sunrise Project mailing list and at events such as the Lawrence Farmers Market. Students will visit the Worm Farm each fall to harvest worms for practical and educational use on site at their schools.

Research

Materials and methods:

From my experience, many worm farmers get caught up on the devices and tools of the process. I have researched and studied the tools and applications and have decided to go with very basic approaches. Instead of creating a flow-through digestor (very expensive) for the worm farm, I have simply created raised beds to facilitate the feeding and breeding of the worms. This has decreased my costs and has allowed me to focus on the worms and the feed sources instead of the tools and implements. I will have more to share about my processes and care for the worms both in terms of breeding and feeding in the final report.

Now at the end of the project I would suggest a few things.

1.) I would keep the worms underground and indoors. Issues of heating, cooling, and the introduction of red mites are big issues and if possible should be avoided. Keeping the worms underground and indoors would protect against these issues.

2.) I would pre-compost foods prior to feeding the worms. Worms do not eat the ripe, raw food. They begin to eat the food once enzymes and micro-organisms begin breaking the food down. Putting raw food into the worm bins is fine for small setups but often leads to unpredictable bin moisture content and provides a prime scenario for pests (red mites) that will devour the ripe foods. Pre-composting eliminates this factor and if the worms are fed in correct amounts at correct intervals then there will be no excess food and excess moisture content to attract the red mites.

3.) My project was very aspirational. It required that I successfully raise the worms and increase their numbers in my first experience working at a larger scale and my first experience growing worms outdoors. It also required that I successfully work with district schools and interact with thousands of students across a range of ages to educate students about food waste and food waste mitigation. It also required that I build a workflow between myself, school staff, school administrators, custodians and lunchroom staff for the food waste audits and composting processes to work. It also required that I then, after having done all of this, convince the school district to fund and adopt this model that had been previously grant funded through KDHE Kansas Green Schools and USDA. My thought looking back is that this is too many large scale intensive factors for a single project. I was able to accomplish everything with the exception of convincing the district to continue the program once grant funding dried up. If I would have removed the aspiration of making this a district wide venture and focused on a smaller scale composting program that sold worms and worm castings at the local farmers market, I believe that would have been a more obtainable model.

Research results and discussion:

The project diverted over 8100 lbs of food waste between 6 schools and 1 grocer in the city of Lawrence, Kansas between 2017-2018.

3,844 students from 6 area schools took part in food waste audits, assemblies, in-class education, and on-site composting with worms.

6 worm bins were constructed for 3 schools and 3 remain in operation well after the grant period.

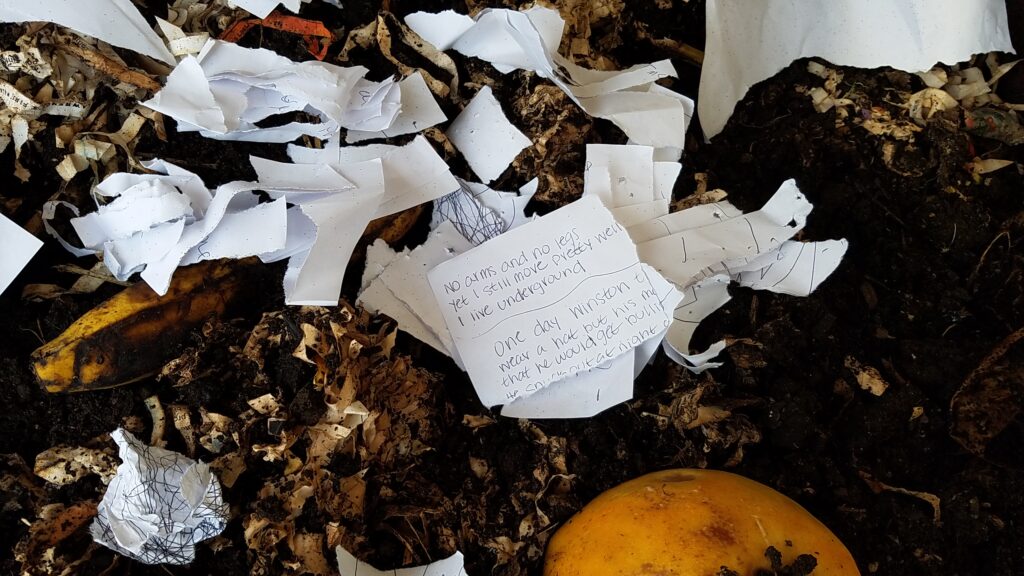

The general discussion around the topics of food waste, composting and worms was a really rewarding experience. Kids made amazing drawings, interacted with worms, helped sort food into groups (compostable, recyclable, trash) and even wrote poems about worms which were then placed into the worm bins to be consumed by the worms. Children and adults alike very much appreciated the project.

6 schools welcomed me into their doors and allowed me to lead their students through hands-on food waste audits. A week-long waste audit was completed for each school. the results including discarded silverware, trays, uneaten fruit, unopened milks and the like were eye-opening for all involved.

Through the food-waste audit process it was recognized that a well meaning nutrition law set into action by Michelle Obama was accounting for a great number of the discarded string cheese and fruit. Students were obligated (for nutrient intake) to take either a fruit or dairy item along with their meal. Since Kansas law does not allow children to share food the unwanted food is discarded. In one day at Free State high we were able to fill an entire 30 gallon tote with unopened milks, string cheese, apples, bananas, and oranges that students were discarding. Students wrote "share bin" on the clear tote and throughout the lunch periods multiple students requested to have foods in the bin. If permitted the "share" bin could provide many healthy lunches for low-income students and students simply wishing to have a snack for later in the day.

Participation Summary

4 Farmers participating in research

Educational & Outreach Activities

20 Consultations

10 Curricula, factsheets or educational tools

12 On-farm demonstrations

1 Published press articles, newsletters

8 Tours

1 Webinars / talks / presentations

35 Workshop field days

5 Other educational activities: I am also partnering with a local grocer which will hopefully result in a promotional/educational campaign partially facilitated by the grocer.

Participation Summary:

3 Farmers participated

2 Ag professionals participated

Education/outreach description:

Learning Outcomes

4 Farmers reported changes in knowledge, attitudes, skills and/or awareness as a result of their participation

Lessons Learned:

Many of the learning outcomes that have developed from this grant have been through the international worm conference I was able to attend in Raleigh NC in October of this year. The conference was great. Presenters from all over the world, presenting on many different approaches to vermiculture, vermicomposting and food waste mitigation spoke on the dynamics and tools of industrial vermiculture and the dynamics and tools of a more social justice based approach to food waste recovery/mitigation/composting. Many of the presenters were directly paired with large bovine operations and were harvesting the solid waste of animals for use in their feed for wormstock. Nearly all of the presenters practiced some form of pre-composting of feedstocks being fed to the worms. Personally I was interested in the tools and approaches of the larger industrial operations happening in more rural areas but truly my interest lies in the implementation of this work in urban areas with high concentrations of generated food waste. There are similar operations to what I am constructing in DC and Austin Texas. There is also a good model in Nottingham England. I've made a point to get into contact/or acquire the contact info for these folks and will be in touch with them as the Lawrence Worm Farm operation grows. There were lots of other details and nuances that tend more towards the science end of things, Some of this made sense to me, some of it is really meant for scientists. One thing that I did learn that will be very helpful for the test plot is that other studies have found between 15-20% worm castings to generally be the best mixture for increasing health and yield.

Education has also come through the trial and error process of growing from a small educational pilot operation into a small-scale operation with business aspirations. The education from the afforded opportunities is ongoing and this is something that I would like to elaborate upon more in the final report.

Both in the spring of 2017 and 2018 the worm bins were visited by small brown, red, and white mites. These mites along with the common black fly larva were pests in the worm bins. The black fly larva are voracious eaters and would consume food before the worms could get to it. Because of this the larva was also easy to remove. Simply place a piece of cantaloupe in the worm bin and a couple hours later the fruit could be removed nearly filled with black fly larva. These larva could then be sprayed off away from the bin and the fruit replaced. This same method works well for the mites, specifically the brown and red mites. In addition to being a nuisance the red mites are also carnivorous and will bore into the worms. Both years I lost a large portion of the worms to these effective but unwanted composters.

In addition to challenges with pests, winter temperatures are also a formidable adversary. During the winter of 2017 I purchased thermostat controlled heating cable and lined the worm beds with this cable. The thermostat had a connected thermometer that could be placed in the bin and the temperature could be set so that the cables would only heat up when the temperature dropped below a desired point. This in theory was an ideal setup and solution to the cold winter weather.

The issue that arose with the heating cables had to do with mice. In the greenhouse there were a number of mice and often (because of the elevated temperature) they would sneak into the worm bins. This was not much of a problem until they began to eat the heating wire. This event occurred while I was back home for Christmas break, and because of the short in the wire caused by these mice I returned to find an entire bed of worms frozen. This also occurred in one bed during the winter of 2018 with one of South West Middle School's worm bins. I'm not currently sure what the solution would be but I imagine there is an available coating or insulator that could be applied to the wires to keep the mice at bay.

In 2019 use of the Sunrise Greenhouse was transferred to One Heart Farms for produce production. The wood from the 2017 - 2018 worm bins was re-purposed by myself and Sunrise Project to construct handicap accessible raised beds for the outdoor space. They are currently in production and serving an alternate but great purpose.

Relationships between Checkers Grocery, New York Elementary, Central Middle School, Prairie Park Middle School, Free State High School, Sunrise Project and Lawrence Worm Farm came to an end in 2018 with the cancellation of the Green Schools grant program. As a consultant and as a general helper I have sustained my relationship with South West Middle School. Currently they have 2 8x3ft bins up and running and will be adding a third bin in the fall of 2019. The systems introduction model used by South West was the most successful and sustaining of all the schools.

What did South West Middle do different than the other schools?

Introduction of the vermicomposting / food waste program was done with a single grade, the 6th grade class. It was the job of these students to learn about composting, waste issues, greenhouse gases, benefits of sustaining the nitrogen cycle etc. Like all the other schools they did the lunch room waste audit, carefully measuring all of the food and separating compostable from recyclable from waste and together we tracked these numbers for a week. This basis served to inform the need for an in-school composting program. When the students moved on to 7th grade, then both the 7th and the new incoming 6th were taking part in the program; this year it's 6th, 7th, and 8th. This approach seemed less overwhelming than trying to get an entire school on board all at once. It also helps that the partnering teachers are deeply dedicated and supportive of the initiative. Without them it would be dead in the water.

My main takeaways from the experience are many fold.

On an economic level, the prospect of the work required, the amount of time and dedication required for organizing and fulfilling tasks and maintaining relationships make the scale at which I was working a full-time job. Without direct support from the municipality, sanitation, the school district or some form of income stream from the composting it is not an economically sustainable venture.

While folks are interested in purchasing worms and worm castings the sales (in my experience) will not generate enough revenue on a person - person scale. If this were occurring on a larger scale with mass delivery of castings and composted materials it might be a different story. I learned early on that my interest was less on the business side of it than on the social / education side of teaching and interacting with students and youth about the benefits of composting food waste and the cool and wonderful magic of worms.

That being said, if a venture like this was backed by a school district or a municipality as a green initiative with 1-2 staff persons it would be a highly beneficial and manageable venture. This is much more likely than it being a sustaining agribusiness as far as I can tell.

Project Outcomes

1 Farmers changed or adopted a practice

9 Grants received that built upon this project

1 New working collaboration

Success stories:

- Through the education component of this project, more than 3,844 Lawrence youths aging 6-18 yrs old took part in workshops, food waste audits, presentations, hands-on composting, and vermicomposting. 6 Lawrence schools participated during the tenure of the Green Schools grants with one remaining an ongoing project participant more than a year after the grants have ended.

- Through this project, more than 8100 total lbs of food waste sourced from 6 schools and one local grocery store was diverted from entering the sanitary landfill.

- Students learned what lunch room items were and were not compostable, they learned about the nitrogen cycle, about industrial food waste, agricultural food waste during production and about consumer food waste. Students were empowered in their role as active participants in affecting the waste stream and expressed this through presentation, posters, conversations, poems and artwork.

- In the spring of 2018 students visiting the Sunrise Project vermicomposting site took part in a project through which they generated poems and haikus about composting and worms. These poems were then ceremonially fed to the worms as a part of the composting process.

Recommendations:

As a stand-alone operation a worm farm is tough to make economically sustainable. On the scale that I was working (include schools, doing educational workshops, partnering with community groups, grocery stores etc.) I wasn't able to make the project economically sustainable. The time requirement and loss of funding was too intensive.

My suggestion would be that this type of project be co-sponsored between a municipality and a school district with 2 paid staff positions as a green initiative towards waste reduction. This is one way that I could imagine the project becoming economically sustainable.

Other recommendations would be less on the funding side and more on the technical side of having a production scale worm bin. Red mites and brown mites are a big concern in our climate. They are hard to tell apart and the red ones will decimate worm populations quickly. I would also advise to not keep worms outdoors during winter months in this climate even if you have a heat source to effectively regulate temperature. (A big part of this is sustainability, heating a bed of worms outdoors when it's 10 degrees out negates that intention.) My suggestion would be to keep them in a space below ground such as a basement or cellar. This sort of geothermal approach makes much more sense.

I would also suggest not putting food directly into the worm bins. It's best to pre-compost foods and to then introduce the partially composted food into the bins. Worms don't eat raw fruits and vegetables, they are more attracted to the food sources once they've began an initial phase of decomposition. Pre-composting might also solve some of the attraction issues for black fly larva and red mites.

I would also suggest that would-be worm farmers really question their goals and intentions with the worm farm. Personally my aspirations while founded on good ideas and successful models were too lofty for the reality of my circumstances and the available infrastructure support of my particular community. The time commitment and necessary partnerships are long term with something like this. Be sure you're up for it if you initiate it. A "build it and they will come" approach isn't necessarily the way to go with something as quirky and multi-faceted as worm farm.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.