Final report for FNC19-1164

Project Information

My wife and three kids purchased a 61-acre farm outside of rural Hettinger, ND in 2017. Raising our family in the country is the primary purpose for the property, but other important goals include raising livestock, growing fruits and vegetables to eat and sell, and providing habitat for wildlife including pollinators. My wife and I would also like to use the property as a “learning center” where local kids can come learn about the land and the benefits society receives by having grasslands on the landscape. Currently about 2/3 of the area is tamed grasslands consisting primarily of crested wheatgrass and alfalfa. The remaining land consists of a series of shelterbelts. Hay has been harvested from the tamed grasslands annually, but in recent years, low productivity has made them not worth cutting. The goal is to improve diversity, and in doing so, increase forage production within these grasslands, and then convert some of the area into a set of grazing pastures which we will use to raise sheep, goats, and maybe cattle, for 4-H projects, our consumption and sale. The remaining area will be managed for forage production, to maximize floristic resources, and to provide greater structured habitats for wildlife. In addition to being used as hay land in years past, honey bees have been stationed on the property by a local beekeeper during the growing season for over 20 years. Increasing diversity in these fields will not only make them more resilient and a better resource to base a small livestock business on, but also improve honey production in the area by increasing floristic resources and providing a safe haven free from insecticides.

I am a rangeland and wildlife research scientist at the Hettinger Research Extension Center. My experience with wildlife, pollinators, livestock and land use in general make me more than qualified to complete this work on our property. On our agricultural landscape, there are currently no properties that I am aware of that are managed with pollinators in mind, making this project not only beneficial for my family, but ecologically important to the landscape.

The primary goal of this project was to increase the resiliency of our grasslands to better provide ecological services to ourselves and society. We are working to achieve this goal through increasing diversity within our grasslands by evaluating a variety of restoration techniques. We developed two separate seed mixes with pollinators, wildlife, and livestock production in mind. One mix consisted of all native plants while the second was a combination of both non-native and native plants. Seed mixes were sown in spring following: 1) A single chemical application in May (2019), 2) Complete restoration including 2-3 chemical applications in 2019, a single chemical application in spring 2020, and spring seed either with oat nurse crop or without, and 3) Chemical application (2019), spring seeded cover crop (2019), and chemical application (2020). Grassland restoration takes time and it is difficult to determine with certainty which seed mix planted under which management regime will produce the most resilient grassland. Regardless, both seed mixes have resulted in grasslands with greater species richness and floral resources available to pollinators. In fact, our grasslands provided habitat for a number of different butterfly species from June through September. While our grasslands appear to be trending in the right direction with respect to establishment, we have learned a couple things that we will put into use during future grassland restorations at our place. First, cover crops have ecological benefits, however, if allowed to mature and set seed, the seed can germinate the following year resulting in a potential increase in competition for desired seedlings. Next, although an added expense, additional applications of glyphosate prior to seeding is likely worth it. Finally, if providing a diverse suite of flowers for pollinators is a goal, including different species of forbs in the seed mix may be warranted as some species are yet to establish, but because we included many different forbs, our grasslands still contained a high number of different flowering plants. The information gained from this project will be used in future grassland restorations at our place beginning in 2021 as well as provide insights for others involved or considering grassland restorations.

- Evaluate methods to increase diversity in grassland restorations.

- One chemical application in May, spring seed.

- Complete restoration (2-3 chemical application (glyphosate), and spring seed either with oat nurse crop or without

- Chemical application, seed cover crop, chemical application, spring seed

- Evaluate early establishment of plants sown under the above methods and consisting of two different seed mixtures (native vs native/non-native).

- Use research plots and adjacent lands to educate kids and producers about grasslands, our project, and the importance of plant diversity.

Research

Project Design

Methods

Our project was carried out in Adams County near the town of Hettinger, North Dakota. The region is semi-arid with warm summers and relatively cold winters. The 30-year average annual precipitation for the region is 16 inches with more than half (9.8 inches) falling during the growing season. Average winter temperature for the area is 21°F and the average summer temperature is 66°F.

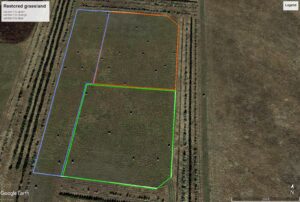

Prior to the onset of research, fields were dominated by non-native grasses and forbs common to the region including smooth bromegrass, crested wheatgrass and alfalfa. In 2019, field 1 was divided into three sections. In May 2019, we applied glyphosate at 1-qt per acre to all of field 1. We then divided field 1 into 3 sections (Figure 1).

Section 1. We planted two different seed mix treatments replicated three times each in section 1 on May 21, 2019. Seed mix one cost ~ $475/acre, and consisted of both native and non-native grasses and forbs totaling 27 species (Table 1). Seed mix two cost ~ $800/acre and consisted of 27 native grass and forb species (Table 1). Seeds were planted with a no-till drill targeting depths of 0.25-0.5 inches.

Section 2. A 14 species cover crop mix was planted in section two on May 21, 2019. The cover crop was planted with a no-till drill and the mix included a combination of grasses and flowering plants. We applied glyphosate at a rate of 1-qt per acre in early-May. We divided section 2 into 6 equal portions and seeded the two seed treatments into 3 portions (replicates) each. Seeds were planted on 22 May, 2020 with a no-till drill targeting depths of 0.25-0.5 inches.

Section 3. Section three was treated with glyphosate two additional times in early-June and July to control weeds in 2019 and again in May 2020. We then divided section 3 into 12 plots. We seeded the two seed treatments in 3 replicates each. We than planted each treatment in 3 additional replicates and added 25lb/acre of oats as a nurse crop. Seeds were planted on 22 May, 2020 with a no-till drill targeting depths of 0.25-0.5 inches.

Vegetation Sampling

We collected pre-data concerning the plant community where our project occurred in summer 2018. We randomly assigned three 25 m transects to each field and assessed canopy cover by species at 5 m increments along each transect using a 0.5 m2 frame. We estimated the non-overlapping percent cover of each species, litter and total bare ground found in each frame. We sampled the plant community across all treatments in 2020 using similar techniques as those outlined above with transects established in each replicate. We collected species composition data in July. We assessed floral resources in perennial cover by counting all flowering stems within 1-m of the line transect. Floral resources were assessed once per month in June-August.

Pollinators

We assessed butterfly abundance along each 25 m transect on the same day floristic resources were evaluated. We counted all butterflies within 10 m of either side of each transect and estimated distance to the individual. We walked back and forth on the transect for 5 minutes and tried not to double count individuals.

Table 1. Species and seeding rate of two perennial plant treatments sown in Hettinger, ND.

|

Non-native/native Treatment – Species |

Pounds pure live seed per acre |

Native Treatment – Species |

Pounds pure live seed per acre |

|

Intermediate wheat grass |

1 |

Green needlegrass |

0.4 |

|

Western wheatgrass |

0.5 |

Junegrass |

0.0 |

|

Beardless bluebunch wheatgrass |

0.5 |

Slender wheatgrass |

0.3 |

|

Canada wild rye |

0.5 |

Western wheatgrass |

0.5 |

|

Green needle grass |

0.5 |

Thickspike wheatgrass |

0.3 |

|

Big bluestem |

0.8 |

Little bluestem |

0.1 |

|

Side oats grama |

1 |

Buffalograss |

0.7 |

|

Blue grama |

0.5 |

Blue grama |

0.3 |

|

Alkali Sacaton |

0.5 |

Sideoats grama |

0.4 |

|

Prairie sandreed |

0.1 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alfalfa (SD common) |

0.3 |

Lewis blue flax |

0.2 |

|

Sainfoin |

1.5 |

Plains coreopsis |

0.2 |

|

Cicer milkvetch |

1 |

Western yarrow |

0.1 |

|

Lewis blue flax |

0.2 |

Purple coneflower |

0.1 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

0.1 |

Blanket flower |

0.2 |

|

Western yarrow |

0.3 |

Canada milkvetch |

0.1 |

|

Purple coneflower |

0.2 |

Purple prairie clover |

0.2 |

|

Blanket flower |

0.2 |

Yellow coneflower |

0.1 |

|

Purple prairie clover |

0.3 |

Maximillian sunflower |

0.4 |

|

Greyhead coneflower |

0.4 |

Butterfly milkweed |

1.1 |

|

Maximillian sunflower |

0.2 |

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0.3 |

|

Butterfly milkweed |

0.3 |

Dotted Gayfeather |

0.3 |

|

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0.6 |

Wild Bergamot |

0.1 |

|

Dotted Gayfeather |

0.2 |

Black-eyed susan |

0.1 |

|

Heath aster |

0.2 |

Greyhead coneflower |

0.4 |

|

Black-eyed Susan |

0.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

12.2 lb/ac |

|

7.0 lb/ac |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Results

Our study was conducted in 2019 and 2020. Overall, 2019 was a much wetter and cooler summer than 2020. April through September precipitation totaled 18.5 inches in 2019 and declined sharply to 6.7 inches in 2020.

Our fields prior to research activities were similar and not species rich with only 7 species occurring on-site. Crested wheatgrass was the dominant plant accounting for nearly 40% of canopy cover, followed closely by smooth brome at 30%. Alfalfa was the dominant forb making up 11% of the overall canopy cover. Western wheatgrass was the most prevalent native species, but still accounted for less than one percent of the cover. Inland salt grass, dandelion, yellow sweet clover and Kentucky bluegrass were also found on-site in small percentages. Roughly 5% of fields prior to treatment establishment were considered bare ground while litter covered roughly 18% of the area.

Section 1. 2020 represented the second growing season since plots were seeded. Species richness was 14 in the native seed treatment and 11 in the non-native/native treatment. Richness was similar in 2019 on the native treatment at 14, but down some in the non-native/native treatment where 18 species were recorded in 2019. Planted cover for seeded species was ~ 43% in the native treatments and ~ 55% in the non-native/native treatment. Alfalfa was included in the non-native/native treatment and accounted for 38% of the total planted cover. In contrast, alfalfa was not included in the native seed treatment and did not contribute to the total planted cover. Nonetheless, alfalfa was common in the native treatments occupying roughly 27% of the canopy cover. In the native treatment, planted grasses made up 17% of the canopy cover while planted forbs made up 26% (Table 2). Side-oats grama had the greatest average cover for planted grasses at ~ 4% while Maximillian sunflower had the greatest cover of planted forbs at 15%. Planted forbs accounted for the majority of the planted canopy cover in the non-native/native treatment with 38% being alfalfa. Maximillian sunflower was the second most prevalent forb and accounted for 6% of the canopy cover (Table 2). Canopy cover of planted grasses in the non-native/native treatment was low at ~ 5%. Remnant grasses remained from the pre-restoration plant community with smooth bromegrass comprising between 3 and 10% of the canopy across treatments.

Section 2. German millet which was included in the 2019 cover crop, was dominant throughout section 2 making up 38% of the cover in the native treatment and 44% in the non-native/native treatment (Figure 2; Table 3). Species richness was 18 in the native treatment and 12 in the non-native/native treatment. Cover of planted grasses and forbs were similar between treatments at 6% and 8%, respectively. Crested wheatgrass and smooth brome were found in section 2 treatments occupying ≤1% of the cover.

Section 3. Species richness ranged between 7 and 9 in treatments regardless if oats were included or not (Table 4). Cover of planted grasses and forbs was 4% in the native treatment when planted with oats and 41% when planted without. Similarly, cover of planted grasses and forbs was greater in the non-native/native treatment when oats weren’t included (32%) versus when they were (25%). Oats occupied between 42 and 57% of the canopy in treatments that included oats. Big bluestem, side-oats grama and Maximillian sunflowers were the most common species found in section 3. Smooth bromegrass and crested wheatgrass were not observed in section 3.

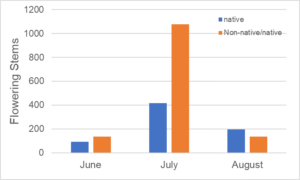

Floral Resources

Section 1. Floral resources peaked in July and August when alfalfa and Maximillian sunflower, the two dominant flowering species were in bloom (Figure 3, Table 5). Five species were flowering in both the native and non-native treatments in June. Native treatments had 9 species flowering in July and 6 in August while 8 species were flowering in non-native/native treatments in July and 6 in August. In general, across these plots, there were more flowers blooming in August of 2019 relative to 2020 (Table 5).

Section 2. No plants along transects were observed flowering outside of Maximillian sunflower and plains coreopsis in this section. Maximillian sunflower averaged 8 flowering stems per transect for both treatments while plains coreopsis had 14 flowers per transect in the native treatment and 15 in the non-native/native treatment.

Section 3. Plants began to flower in late-July regardless if planted with oats or not (Table 6). Plains coreopsis and Maximillian sunflower were the two most common flowering plants across all treatment (Table 6). Though we did not assess floral resources in September, 2020, visual observations revealed heavy flowering of Maximillian sunflower and other plants throughout the beginning of September (Figure 4).

Butterfly Surveys

Instead of breaking down butterfly surveys by planting date and treatment, we choose to report the monthly average number of butterflies observed along each transect across the entire restoration (Table 7). Butterfly numbers varied across months with a low of 55 counted during June surveys and a high of 119 observed in July. The most frequently observed species also varied with Melissa blue and cabbage white common during June surveys and clouded sulfurs most common in July (Table 7).

Discussion

Many restored grasslands found throughout the North-Central Region lack diversity and struggle to provide ecological services to society (forage for livestock and pollinators). As grasslands continue to be converted to other uses, future restoration efforts should work to promote resilient grasslands that increase diversity and maximize ecological services. Here, we evaluated two seed mixes; the first a native seed mix and the second a mix that consisted of both native and non-native plants, seeded under a variety of situations across two years. We developed our seed mixes to provide forage for livestock and floral resources for pollinators. Because grasses tend to become more common over time at the expense of forbs, our seed mixes included a greater proportion of forbs than is typically used in grassland restorations with the expectation of maintaining a strong forb community into the future. Forb seed accounted for 52% of seed weight in the non-native/native mix and 56% in the native mix. Following two growing seasons, plants in section 1 appear to be establishing across both treatments as canopy cover of planted species are increasing. Both mixes two years post-seeding have resulted in a more species rich grassland than previously existed prior to restoration efforts. Slender wheatgrass and side-oats grama had the greatest cover of native grasses in the native planting while despite being in very low percentages, side-oats grama and green needle grass were the most common grasses in the non-native/native mix.

Grassland restorations, especially those associated with native plants can take years before the final outcome can be predicted. The outcome can be heavily influenced by precipitation amounts and timing. We had above average rain in 2019, but below average precipitation in 2020. This may have given plants, like alfalfa that establish early and can tap into moisture reserves an edge over those that require more time before emergence. Alfalfa was common in both treatments despite only being included in the non-native/native treatment. Section 1 received only a single application of glyphosate prior to planting and this was likely not sufficient to eradicate alfalfa from the original grassland. Therefore, alfalfa has been able to survive and appears to be on the increase. Our concern with the planting in section 1 is that the one application of glyphosate may not have killed off all existing plants prior to restoration and over time, the alfalfa, smooth brome and crested wheatgrass will outcompete the other grasses and forbs. Time will tell. Despite the ecological services provided by alfalfa, we will target management actions to prevent it from becoming dominant.

Restoration plantings completed in 2020 received little moisture until late-June and July, likely suppressing seed germination for some species. In section 2, the area planted to a cover crop in 2019, volunteer millet germinated prior to some seeded plants and may have further restricted establishment beyond the general lack of rain. Landowners and managers interested in planting a cover crop prior to grassland restoration should consider terminating the cover crop prior to flowering as seed could impact the long-term outcome of a grassland restoration. However, flowers associated with cover crops may benefit pollinators. Despite the lack of moisture and establishment of volunteer millet, species richness of planted cover was well above that found in the original planting. Percent cover of planted species was low in both treatments which is expected in first year plantings.

Nurse crops are sometimes used during grassland restorations. We found that at our farm, seeding oats with perennial grasses and forbs reduced the percent canopy cover of perennial plants. Native grasses and forbs that can take longer to establish than non-native plants, accounted for 32% of the cover when seeded without oats versus 4% when oats were included. Similarly, planted perennial cover was 41% in the non-native/native treatment when oats were not included and 25% when they were. However, our results represent only one growing season and we expect changes in the plant community to occur over time, some of which may show benefits associated with the nurse crop. One benefit of planting oats with perennials is the wildlife appreciate the winter food source. Having oats interspersed with bare ground, perennial plants and annual weeds makes fantastic winter cover for upland birds.

The seeds associated with our study mixes were expensive. Elevated costs were associated with many of the native forbs and grasses. It is difficult to accurately assess with any degree of certainty which mix was more cost affective relative to the other given the newness of restoration efforts. Nonetheless, there are some commonalities in species between mixes that have established and should be strongly considered in future plantings. Maximillian sunflower and plains coreopsis are two forbs that did well regardless of mix while side-oats grama was a common grass found throughout restored grasslands.

Restoration efforts at our farm have resulted in greater floral diversity than previously existed with fields supporting flowers with an array of shapes, sizes, colors, and blooming periods. Assessing butterflies in small plots proved difficult as they freely fly from one treatment to the next. Nonetheless, we found that our fields provided for numerous different species of butterfly from June through August. Furthermore, our results show that providing flowering resources to pollinators throughout the growing season is important as the species we recorded using our fields shifted over time.

Management Implications

Our grassland restorations are in their infancy and we expect changes in the plant community to occur over time. However, based on what we’ve observed we offer a couple of suggestions that may be of use going forward. First, one application of glyphosate is likely not sufficient to kill perennial cover prior to seeding. Additional applications of glyphosate prior to seeding, though an added expense is likely worth it. Second, the use of cover crops prior to planting perennial grasses and forbs may have benefits, but could also have the potential to introduce a huge amount of seed to the seedbed if not managed properly. We let our cover crop reach maturity which allowed pollinators to use flowers and provided food for wildlife, but also introduced competition for seedlings in 2020 when millet seed germinated. Instead of using chemical to terminate the cover crop prior to seed set, an alternative option may be to allow livestock to graze the cover crop while it is blooming which in return may allow flowering but prevent some seed set. Third, although very premature, it may be important to include many species of forbs during seeding if providing a diverse suite of floristic resources is important as many of the different forb species we included have not been found in the fields as of yet.

Moving Forward

We intend to leave the restored area idle in 2021. However, managing these fields to maintain floristic resources will be a priority moving forward and we intend to conduct research to find the best way to maintain flowers in our fields. We also intend to fence the restored area and begin grazing livestock in spring 2022. Finally, we intend to use the information gleaned during this project to restore the remaining grasslands on our farm.

Table 2. Canopy cover of planted species two years post-seeding in section 1. Section 1 was treated once with glyphosate prior to seeding in May, 2019.

|

Non-native/native Treatment – Species |

% Canopy Cover |

Native Treatment – Species |

% Canopy Cover |

|

Intermediate wheatgrass |

0 |

Green needlegrass |

1 |

|

Western wheatgrass |

<1 |

Junegrass |

0 |

|

Beardless bluebunch wheatgrass |

0 |

Slender wheatgrass |

9 |

|

Canada wild rye |

1 |

Western wheatgrass |

2 |

|

Green needle grass |

1 |

Thickspike wheatgrass |

0 |

|

Big bluestem |

0 |

Little bluestem |

0 |

|

Side oats grama |

1 |

Buffalograss |

0 |

|

Blue grama |

1 |

Blue grama |

1 |

|

Alkali Sacaton |

1 |

Sideoats grama |

4 |

|

Prairie sandreed |

0 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alfalfa (SD common) |

38 |

Lewis blue flax |

2 |

|

Sainfoin |

0 |

Plains coreopsis |

3 |

|

Cicer milkvetch |

0 |

Western yarrow |

2 |

|

Lewis blue flax |

0 |

Purple coneflower |

1 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

1 |

Blanket flower |

0 |

|

Western yarrow |

1 |

Canada milkvetch |

0 |

|

Purple coneflower |

1 |

Purple prairie clover |

0 |

|

Blanket flower |

0 |

Yellow coneflower |

0 |

|

Purple prairie clover |

0 |

Maximillian sunflower |

15 |

|

Greyhead coneflower |

0 |

Butterfly plant |

1 |

|

Maximillian sunflower |

6 |

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0 |

|

Butterfly Plant |

<1 |

Dotted Gayfeather |

0 |

|

Shell-leaf penstmon |

1 |

Wild Bergamot |

1 |

|

Dotted Gayfeather |

1 |

Black-eyed susan |

1 |

|

Heath aster |

1 |

Greyhead coneflower |

0 |

|

Black-eyed Susan |

<1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3. Canopy cover of planted species during the first growing season post-seeding in section 2. Glyphosate was applied once in 2019, planted to a cover crop in 2019, treated with glyphosate again in 2020, and seeded in May, 2020.

|

Non-native/native Treatment – Species |

% Canopy Cover |

Native Treatment – Species |

% Canopy Cover |

|

Intermediate wheatgrass |

2.8 |

Green needlegrass |

0.8 |

|

Western wheatgrass |

1.2 |

Junegrass |

0 |

|

Beardless bluebunch wheatgrass |

0.6 |

Slender wheatgrass |

0.4 |

|

Canada wild rye |

0 |

Western wheatgrass |

0.8 |

|

Green needle grass |

0.4 |

Thickspike wheatgrass |

0 |

|

Big bluestem |

0.4 |

Little bluestem |

0 |

|

Side oats grama |

1.2 |

Buffalograss |

0 |

|

Blue grama |

0.2 |

Blue grama |

0.4 |

|

Alkali Sacaton |

0 |

Sideoats grama |

1.6 |

|

Prairie sandreed |

0 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alfalfa (SD common) |

4.6 |

Lewis blue flax |

0.8 |

|

Sainfoin |

0.6 |

Plains coreopsis |

1.4 |

|

Cicer milkvetch |

0 |

Western yarrow |

0.8 |

|

Lewis blue flax |

0 |

Purple coneflower |

0.2 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

0 |

Blanket flower |

0 |

|

Western yarrow |

0 |

Canada milkvetch |

0.4 |

|

Purple coneflower |

0 |

Purple prairie clover |

0 |

|

Blanket flower |

0 |

Yellow coneflower |

0 |

|

Purple prairie clover |

0 |

Maximillian sunflower |

1.8 |

|

Greyhead coneflower |

0 |

Butterfly plant |

0.6 |

|

Maximillian sunflower |

1 |

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0 |

|

Butterfly Plant |

0 |

Dotted Gayfeather |

0 |

|

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0 |

Wild Bergamot |

0.6 |

|

Dotted Gayfeather |

0 |

Black-eyed susan |

0.6 |

|

Heath aster |

0 |

Greyhead coneflower |

0 |

|

Black-eyed Susan |

0.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4. Canopy cover of planted species during the first growing season post-seeding in section 3. Glyphosate was applied three times in 2019, treated with glyphosate again in 2020, and seeded in May, 2020.

|

Non-native/native Treatment – Species |

% Canopy Cover |

Non-native/native Treatment W/oats – Species |

% Canopy Cover |

|

Intermediate wheatgrass |

0 |

Intermediate wheatgrass |

0 |

|

Western wheatgrass |

0.2 |

Western wheatgrass |

0 |

|

Beardless bluebunch wheatgrass |

0 |

Beardless bluebunch wheatgrass |

0 |

|

Canada wild rye |

0 |

Canada wild rye |

0 |

|

Green needle grass |

0.2 |

Green needle grass |

1 |

|

Big bluestem |

0.4 |

Big bluestem |

0.2 |

|

Side oats grama |

8.6 |

Side oats grama |

1.6 |

|

Blue grama |

0 |

Blue grama |

0.2 |

|

Alkali Sacaton |

0 |

Alkali Sacaton |

0 |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alfalfa (SD common) |

1.4 |

Alfalfa (SD common) |

18 |

|

Sainfoin |

0 |

Sainfoin |

0.2 |

|

Cicer milkvetch |

0 |

Cicer milkvetch |

0 |

|

Lewis blue flax |

0 |

Lewis blue flax |

1.2 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

2.8 |

Plains coreopsis |

0 |

|

Western yarrow |

0 |

Western yarrow |

0 |

|

Purple coneflower |

0 |

Purple coneflower |

0 |

|

Blanket flower |

0 |

Blanket flower |

0 |

|

Purple prairie clover |

0 |

Purple prairie clover |

0 |

|

Greyhead coneflower |

0 |

Greyhead coneflower |

0.2 |

|

Maximillian sunflower |

15.4 |

Maximillian sunflower |

2 |

|

Butterfly Plant |

2 |

Butterfly Plant |

0 |

|

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0 |

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0 |

|

Dotted Gayfeather |

0 |

Dotted Gayfeather |

0 |

|

Heath aster |

0 |

Heath aster |

0 |

|

Black-eyed Susan |

0.6 |

Black-eyed Susan |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Native Treatment – Species |

% Canopy Cover |

Native Treatment W/oats – Species |

% Canopy Cover |

|

Green needlegrass |

2.4 |

Green needlegrass |

0.4 |

|

Junegrass |

0 |

Junegrass |

0 |

|

Slender wheatgrass |

0 |

Slender wheatgrass |

0 |

|

Western wheatgrass |

0.2 |

Western wheatgrass |

0.4 |

|

Thickspike wheatgrass |

0 |

Thickspike wheatgrass |

0 |

|

Little bluestem |

5.4 |

Little bluestem |

0 |

|

Buffalograss |

0 |

Buffalograss |

0 |

|

Blue grama |

4 |

Blue grama |

0 |

|

Sideoats grama |

6 |

Sideoats grama |

0.6 |

|

Prairie sandreed |

0 |

Prairie sandreed |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lewis blue flax |

0 |

Lewis blue flax |

0 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

0 |

Plains coreopsis |

0.4 |

|

Western yarrow |

0 |

Western yarrow |

0 |

|

Purple coneflower |

0 |

Purple coneflower |

0 |

|

Blanket flower |

0 |

Blanket flower |

0 |

|

Canada milkvetch |

0 |

Canada milkvetch |

0 |

|

Purple prairie clover |

0 |

Purple prairie clover |

0.2 |

|

Yellow coneflower |

6 |

Yellow coneflower |

0 |

|

Maximillian sunflower |

7.2 |

Maximillian sunflower |

0.2 |

|

Butterfly plant |

0.2 |

Butterfly plant |

0.4 |

|

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0 |

Shell-leaf penstmon |

0 |

|

Dotted Gayfeather |

0 |

Dotted Gayfeather |

0 |

|

Wild Bergamot |

0 |

Wild Bergamot |

0 |

|

Black-eyed susan |

0 |

Black-eyed susan |

0 |

|

Greyhead coneflower |

0 |

Greyhead coneflower |

0 |

Table 5. Average number of flowering stems per 25 m transect in two different plantings established in section 1 in 2019 in Hettinger, ND.

|

Treatment |

August 2019 |

September 2019 |

June 2020 |

July 2020 |

August 2020 |

|

Non-native/Native |

|

|

|

||

|

Max sunflower |

30.7 |

17.0 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

Black-eyed Susan |

7.3 |

11.0 |

0 |

10 |

4 |

|

Blanket flower |

16.7 |

10.0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

|

Butterfly Plant |

6.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Flax |

7.7 |

0.3 |

0 |

14 |

5 |

|

Yarrow |

0.7 |

1.3 |

2 |

14 |

0 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

26.3 |

6.3 |

4 |

7 |

5 |

|

Purple coneflower |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Alflafa |

26.0 |

8.3 |

35 |

449 |

0 |

|

Yellow coneflower |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Sanfoin |

0.0 |

0.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Native |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Max sunflower |

27.3 |

54.7 |

0 |

0 |

58 |

|

Black-eyed Susan |

16.7 |

23.0 |

0 |

10 |

3 |

|

Blanket flower |

7.0 |

13.7 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

|

Butterfly plant |

20.0 |

2.7 |

0 |

1 |

0.5 |

|

Flax |

1.0 |

0.3 |

14 |

11 |

0.5 |

|

Yarrow |

0.0 |

1.0 |

3 |

8 |

0 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

38.3 |

41.0 |

0 |

18 |

3 |

|

Purple coneflower |

0.7 |

0.0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Alflafa |

14.3 |

12.3 |

11 |

75 |

0 |

|

Yellow coneflower |

0.7 |

1.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 6. Average number of flowering stems per 25 m transect in two different seed mixtures seeded with and without oats as a cover crop in May 2020 in Hettinger, ND.

|

Treatment |

June 2020 |

July 2020 |

August 2020 |

Treatment |

June 2020 |

July 2020 |

August 2020 |

|

Non-native/Native – |

|

|

|

Non-native/Native w/oats - |

|

|

|

|

Max sunflower |

0 |

0 |

14 |

Max sunflower |

0 |

0 |

14 |

|

Black-eyed Susan |

0 |

0 |

2 |

Black-eyed Susan |

0 |

0 |

9 |

|

Blanket flower |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Blanket flower |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Butterfly Plant |

0 |

0 |

2 |

Butterfly Plant |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Flax |

0 |

1 |

4 |

Flax |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Yarrow |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Yarrow |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

0 |

0 |

59 |

Plains coreopsis |

0 |

0 |

82 |

|

Purple coneflower |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Purple coneflower |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Alflafa |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Alflafa |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Yellow coneflower |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Yellow coneflower |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Sanfoin |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Sanfoin |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Native – |

|

|

|

Native – w/oats |

|

|

|

|

Max sunflower |

0 |

0 |

27 |

Max sunflower |

0 |

0 |

20 |

|

Black-eyed Susan |

0 |

0 |

3 |

Black-eyed Susan |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

Blanket flower |

0 |

0 |

3 |

Blanket flower |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Butterfly plant |

0 |

0 |

2 |

Butterfly plant |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

Flax |

0 |

0 |

21 |

Flax |

0 |

0 |

12 |

|

Yarrow |

0 |

0 |

7 |

Yarrow |

0 |

0 |

7 |

|

Plains coreopsis |

0 |

1 |

76 |

Plains coreopsis |

0 |

0 |

89 |

|

Purple coneflower |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Purple coneflower |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Alflafa |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Alflafa |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Yellow coneflower |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Yellow coneflower |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Table 7. Average number of butterflies observed along 25 m transects in a restored grassland in Hettinger, ND.

|

|

June |

July |

August |

|

Cabbage White |

18 |

4 |

9 |

|

Checkered White |

1 |

17 |

21 |

|

Clouded Sulfur |

1 |

57 |

20 |

|

Common Ringlet |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Common Woodnymph |

0 |

13 |

9 |

|

Melissa Blue |

21 |

3 |

10 |

|

Northern Crescent |

0 |

8 |

1 |

|

Orange Sulfur |

1 |

8 |

3 |

|

Silvery Blue |

11 |

9 |

18 |

|

Total |

55 |

119 |

91 |

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

We hosted youth hunting events in October of 2019 and 2020. As part of the event, youth were taught about gamebird habitat and the importance of flowering plants to insects and the importance of insects to young chicks. As part of the hunt, we stopped in the restored field and discussed the project. It was a good opportunity for us to share the importance of grassland heterogeneity and management options that may promote such grasslands.

Presented to 1st graders at Hettinger Public School about honeybees and highlighted the importance of diverse grasslands for honeybees and other pollinators.

Completed a power point presentation that outlines the project and describes our early results. Currently working to format video for upload to my YouTube channel.

Learning Outcomes

We learned that restoring diversity through grassland restorations can take time and are likely highly influenced by precipitation. We learned that at least in the short-term, if cover crops are used prior to or as part of grassland restoration, care should be taken to prevent/limit seed set, as volunteer plants may compete with desired plants. We learned that nurse crops such as oats may limit early establishment of desired plants when planted at a rate of 25 pounds per acre. We leaned that our restored grasslands support a diverse set of butterflies from June through August. We learned that grassland restorations are costly and require a lot of time and effort, but the diversity of grasses and flowers we have observed in these grasslands make it all worth while.

We now have a great deal of information that will help us restore additional grasslands in the future. We also now have diverse grasslands that will help provide food for our family through livestock production. We have grasslands on our property that will help meet the requirements of native pollinators, but will also provide substantial floristic resources for honeybees throughout the growing season, which in return provides financial compensation or honey for our family from the cooperating beekeepers.

The lack of diversity in our grassland likely reduced it's resiliency or ability to deal with a changing climate creating a long-term barrier with respect to providing a full suite of ecological services. We are working to overcome this barrier by restoring the grasslands to include a greater diversity of plants capable of withstanding a greater range of conditions. While it is early to say for certain, it does appear that our restoration efforts have improved species richness and diversity over that of our original grasslands and time will tell how resilient they are to a changing environment.

Outside of the work and capital, I think there are nothing but advantages. The floristic and grassland resources I've observed in our grasslands early on have been fantastic. Perhaps the one disadvantage may be if we depended on the grasslands for livestock forage prior to restoration as the restoration process may require livestock to be excluded from the restored areas, at least early on which could result in a loss of forage for a year or two while grasslands are establishing.

We've provided a lot of useful information as part of this report, but if someone asked for an additional recommendation it would be to start small and restore a small portion of your grassland at a time trying a number of different things to see what works on your farm given your soil conditions. Learning as you go, will likely streamline future restorations making them less expensive because you will have learned what will and won't grow in your area. I would also recommend anyone trying to establish native grasslands be patient as some species may take years to establish.