Final report for FNC19-1170

Project Information

Abby and Nick Johnson are owners of Ox Heights, a 170-acre farm in Molkte Township, Presque Isle County, MI, five miles south of Lake Huron. Thirty acres are row cropped with a rotation of hay, corn, soybeans, and wheat. The forage is fed to our small herd of dairy goats and sheep (n=30). Some of the land is leased for $20 per acre to a local cattle farmer. The tillable land was purchased for $1,200/acre in 2010. 130 acres are dedicated to timber production. The deep well drained soils provide excellent substrate for producing quality hardwood timber. We specialize in the sustainable production of veneer and grade logs of sugar maple, red maple, white birch, yellow birch, and white cedar. Trees are hand harvested.

Abby and Nick were educated in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources at Michigan State University. Abby earned her B.S. in Biosystems Engineering during 2009. She is raising our five children ages 10, 9, 6, 5, and 2 and manages chores around the farm. Nick earned his B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. in Biology and Fisheries Management and works a full-time job as a fish biologist. He serves as an adviser for the Michigan Forestry Assistance Program. We have grown to love this region of Northeast Michigan and chestnuts.

During 2017, 435 hybrid Japanese/European grafted chestnut trees were planted on a ridge in Northeast Michigan near Lake Huron where chestnut trees have not traditionally been grown; SARE grant FNC17-1081. Tree survival was 99%, terminal growth in year 1 was 1-2 ft., and some nuts were produced. Starting in 2019, the establishing chestnut trees will need fertilizer. Aged manure could be a very good fertilizer for establishing chestnuts because manure is likely to increase soil organic matter, provide macro and micro nutrients, increase moisture availability, and improve winter survival by insulating the ground. But manure has never been tested or evaluated as a soil amendment for establishing chestnuts according to Chestnut Growers of America and the Australian Nutgrower. Therefore, we proposed an experiment where manure aged roughly 7 months will be applied around some trees and the inorganic fertilizer recommended by Michigan State University will be applied around remaining trees, comparing both tree health and soil outcomes. The project promotes sustainable, diversified agriculture by revealing options for enhancing chestnut orchard establishment, while also managing manure on our farm and reducing inorganic fertilizer use. A blog, video, field day, and presentation at a nut growers meeting will disseminate results.

- (1) Evaluate the feasibility of using aged manure in lieu of inorganic fertilizer during chestnut orchard establishment by evaluating tree survival, growth, nut production, and soil health.

- (2) Disseminate information regarding the feasibility of using aged manure in lieu of inorganic fertilizer during chestnut orchard establishment results through a blog, conference presentation, field day, and final report to SARE.

Cooperators

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

Research

Basic Fertilizer Recommendations from Michigan State University

Michigan State University (MSU) recommends standardizing fertilizer application at 2 oz. of nitrogen per chestnut tree per year for trees 2 years old and at 4 oz of nitrogen per tree for trees 3 years old. They recommend that application occur in the spring shortly after bud burst.

Inorganic Fertilizer Description:

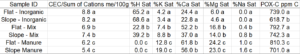

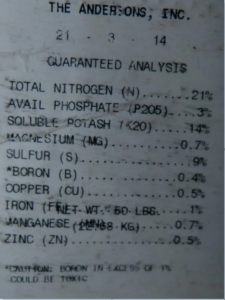

Several chestnut growers recommend using Higgins Mix inorganic fertilizer. Higgins Mix was developed by retired MSU Forestry Professor Norm Higgins. It contains ammonium sulfate (21%) and micro-nutrients (Figure 1). Ammonium sulfate fertilizers reduce soil pH. Chestnuts prefer soil pH between 5.0 and 6.5, so the acidifying characteristics of Higgins Mix is not perceived negatively. For trees receiving only Higgins Mix, in 2019, 10 oz of Higgins mix was applied in a single application in late May (bud break). In 2020, 20 oz was applied total and was spilt into two applications the first being in mid-May and the second being in mid-June.

Organic Fertilizer Application:

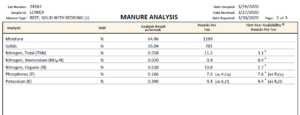

Goat/cattle manure used in 2019 began aging November 2018 (Figure 2). Based on the manure analysis (Figure 3), an average of 4.3 lbs of nitrogen per ton of manure was bioavailable during 2019 (converted to 68.8 oz/ton and then 0.0344 oz/lb). Therefore, we applied a target rate of 58 lbs. manure per tree to provide 2 oz. Nitrogen in spring of 2019.

Figure 2. Goat and oxen manure started the aging processes November 2018.

Manure Sample Report Chestnut 2019

Figure 3. Nutrient analysis of aged manure applied to chestnuts during April 2019.

Manure used in 2020 began composting in fall 2019 (Figure 4) and nutrient analysis in spring 2020 showed an average available nitrogen of 3.1 lbs/ton or about 0.02478 oz/lb (Figure 5). Because manure can retain and release nitrogen over several years, an estimated nitrogen credit of 12% from the organic nitrogen applied in 2019 was used to calculate the amount of nitrogen to be applied in 2020 (0.8 oz of nitrogen available in 2020 from manure applied in 2019). Therefore, to apply an additional 3.2 oz of nitrogen per tree = 129 lbs of manure per tree was applied for organic only treatments.

According to the Food Safety and Modernization Act (FSMA) Produce Rule, un-composted manure must be applied and incorporated 120 days before harvest of a crop that contacts the soil, such as chestnuts. Manure was applied April 2019 and 2020, meeting the 120 day standard because nut harvest occurred in mid October.

Mix of inorganic and organic fertilizer treatment:

Trees receiving a mix of inorganic and organic fertilizer treatment received ½ of the full dose of each fertilizer type.

Assignment of which trees received each fertilizer treatment:

Fertilizer treatments were systematically assigned to trees (1/3rd received inorganic only, 1/3rd received mix, 1/3rd received organic only) to control for variability in soils, topography, wind, and temperature (Figures 6, 7, 8). Six cultivars of chestnut trees are grown in our orchard, so results for each fertilizer treatment were reported according to each cultivar. Colossal (C) and Bouche de Betizac (BB) are cultivars selected for nut production and are most numerous (sample size of about 50 trees per fertilizer treatment). Labor Day (LD), Marigoule (Mg), Marosol (Ms), and Precoce Migoule (PM) are pollinators and are less numerous (sample size of about 8 trees per fertilizer treatment).

Figure 6. Application of 10 oz of Higgins mix using a cup.

Figure 7. Buckets proved to be efficient distribution devices for aged manure. 12 gallons of manure equaled approximately 58 lbs.

Figure 8. Systematic application of manure only (58 lbs), 50/50 mix (29 lbs manure, 5 oz. Higgins), and Higgins only (10 oz. Higgins) to the rows of trees in the orchard.

Survival from Spring 2019 to Fall 2020:

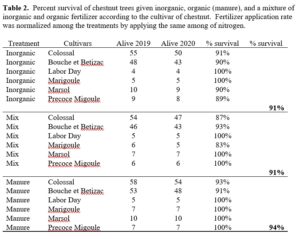

To quantify percent survival according to cultivar and fertilizer treatment, the number of chestnut trees that were alive above the graft in fall 2020 was divided by the number of chestnut trees alive above the graft spring 2019. Since nearly all mortality occurs over the winter, the approach used evaluated survival over winter 2019-2020 after fertilizer application in spring 2019.

Growth from Fall 2019 to Fall 2020:

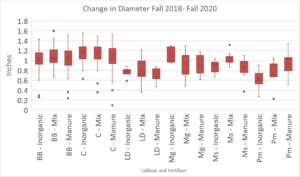

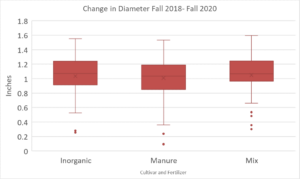

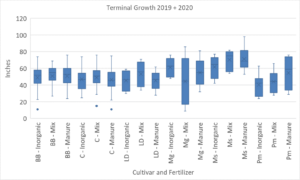

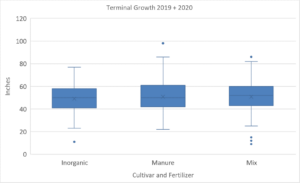

Trunk diameter 18 inches from the ground was measured fall 2018, 2019, and 2020 to determine changes in diameter between fall 2018 and fall 2020 expressed as increase in inches. Terminal growth was measured fall 2019 and 2020 and summed to calculate total new terminal growth during 2019 + 2020. Results are summarized according to cultivar and fertilizer treatment.

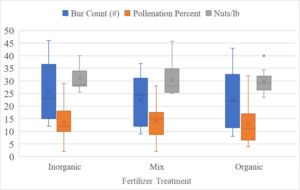

Pollination and nut production 2020:

In October 2020, 36 colossal chestnut trees were surveyed for nut production; 13 were treated with inorganic fertilizer, 13 with organic fertilizer, and 10 with a mix of inorganic and organic fertilizer. The number of burs and pollinated nuts were counted on each tree. The aggregate weight of all the nuts harvested from each tree was measured and the number of nuts required to yield a pound was calculated by dividing the total weight of the nuts by the number of nuts.

Soil chemistry fall 2020:

Thirty composite soil samples were collected (n=10 Inorganic, n=10 ½ inorganic ½ manure, n= 10 manure). 15 composite samples were collected from the high flat portion of the orchard where soil erosion historically has been minimal (5 composite samples per treatment). The other 15 composite samples were collected from a sloped portion of the orchard where water erosion was historically common (5 composite samples per treatment).

A composite sample for a treatment was collected by using a soil probe to obtain 8-inch soil cores from around 3 different trees of the same fertilizer treatment in the same area of the orchard. At each tree sampled, 4 cores were collected under the tree drip zone; one in each cardinal direction. The cores from the three trees for each composite sample were combined and mixed. After mixing, 2-3 cups of soil were placed in a labeled ziplock bag. The samples were processed by Ward Laboratories, Inc. within 1 week of collection. Samples were analyzed for macro and micronutrients and active labile carbon.

Cost of Fertilizer:

We calculated the cost and time required to apply the fertilizer treatments in 2019 and assumed the results would be consistent between years. In 2019, Higgins Mix cost $36 for 50 lbs and because 10 oz of Higgins Mix was needed to apply 2 oz of available nitrogen, the cost of Higgins Mix fertilizer per tree was $0.45 (Table 1). Higgins mix was applied to the orchard at a rate of 1 tree per minute. Assuming a $15 per hour pay rate, labor costs to apply Higgins Mix was $0.25 per tree, meaning the total cost to apply Higgins Mix only was $0.70 per tree. Manure is a waste product from our goat and cattle farming operation, so aged manure was assumed to have zero cost. Aged manure was applied to the orchard at a rate of about 2.4 minutes per tree. Assuming a $15 per hour pay rate, labor costs (and the total cost) to apply aged manure was $0.60 per tree. The 50/50 mix of manure and Higgins Mix cost $1.08 per tree to purchase and apply (labor doubled because they were not applied on the same day; two visits to tree required).

Table 1. Cost for fertilizer and labor to apply fertilizer expressed as a cost per tree.

| Fertilizer Treatment | Cost of Fertilizer per Tree | Cost of Labor per Tree | Total Cost per Tree |

| Higgins | $0.45 | $0.25 | $0.70 |

| 50% Higgins and 50% Manure | $0.23 | $0.85 | $1.08 |

| Manure | $0.00 | $0.60 | $0.60 |

2019 Weather:

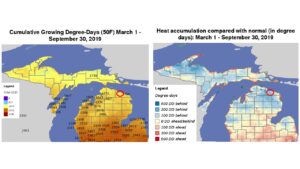

Weather during 2019 was much cooler and wetter than average. Heat accumulation was about 400 growing degree days (base 50) below normal (Figure 9). About 23 inches of rain fell between April 1st and October 31st, 2019, and is about 4 inches greater than the long term average. Irrigation was only applied once to the orchard during 2019. Winter 2019-Winter 2020 was above average in temperature and had near average precipitation.

Figure 9. Heat accumulation in Northern Michigan during the 2019 growing season. Location of Ox Heights is circled. Data taken from Michigan State University Environweather Network.

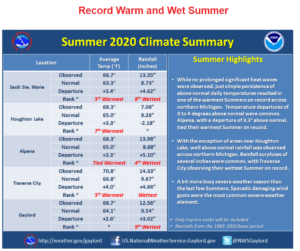

2020 Weather:

Summer 2020 was the warmest on record and the 4th wettest on record in nearby Alpena (Figure 10). Irrigation was applied 2 times per week from middle June to early July. Temperatures and precipitation were near normal in the fall.

Survival from Spring 2019 to Fall 2020:

Results:

About 8% of the chestnut trees died above the graft between fall 2019 and fall 2020, with most of the death observed in May and June 2020. The rootstock was alive on nearly all the trees that died above the graft. Graft failure was attributed nearly 100% to the presence of ambrosia beetle. Survival of trees given manure fertilizer was slightly higher than those receiving inorganic and a mix of inorganic and manure (Table 2).

Discussion: Ambrosia beetles caused nearly all the graft failures in our orchard between fall 2019 and fall 2020 (Figure 11). Prior to 2020, we were not aware that ambrosia beetles were a threat to small chestnut trees and therefore we did not control their populations. The beetles likely originated in the neighboring woodlot where American Beech trees recently died of beech bark disease. In future years, ambrosia beetles will be controlled in the spring through the application of pyrethrin to tree trunks and ethanol-based traps.

Ambrosia beetles attack stressed trees when buds are swelling. Sugars in stressed trees ferment to alcohol. Ambrosia beetles locate stressed trees by locating sources of alcohol (ethanol). Therefore, trees that died above the graft were stressed for some reason, but the reason does not appear to be related to soil chemistry, since mortality rate did not differ substantially among the fertilizer treatments. Most of the mortality occurred in the sloped area in our orchard where soils are sandier. Furthermore, we observed this summer that many locations on the sloped land has a soil hardpan located 12-18 inches deep. Therefore, we suspect that tree stress was related more to the prevalence of the soil hardpan rather than differences in soil chemistry. In other words, differences in soil structure and profile seem to be a more likely contributor to tree death than soil chemistry in the top 8 inches of the soil. Trees that were stressed were attacked by ambrosia beetles and the combination of stress and beetle attack resulted in death of the graft (but not root stock).

Growth from Fall 2019 to Fall 2020:

Chestnut trees grew vigorously in the orchard with terminal growth averaging between 24 and 36 inches each year (Figures 13 and 14). Trees increased in diameter from an average of about 0.5 inches in fall 2018 to an average of 1.5 to 2.0 inches in fall 2020. Marigoule and Marsol cultivars had the most terminal growth, averaging nearly 36 inches of upright growth per year. Bouche de Betizac and Colossal had the largest gains in trunk diameter, with Colossal trees exhibiting outward growth (bushy).

Discussion: Growth did vary substantially among individual trees, but little of the variability was correlated to fertilizer treatment. Growth trended higher in trees receiving composted manure fertilizer treatments relative to inorganic fertilizer (Higgins Mix), but the difference was not overwhelming (Figures 15, 16, 17, 18).

Figure 15. Change in chestnut tree trunk diameter 18 inches from the ground between fall 2018 and fall 2020. Data are summarized by cultivar: BB = Bouche de Betizac ; C = Colossal; LD = Labor Day; Mg = Marigoule; Ms = Marasol; Pm = Precoce Migoule and then by fertilizer treatment.

Figure 16. Change in chestnut tree trunk diameter 18 inches from the ground between fall 2018 and fall 2020. Data are summarized fertilizer treatment and consists of all cultivars

Figure 17. Total terminal growth of chestnut trees during 2019 and 2020. Data summarized by cultivar: BB = Bouche de Betizac ; C = Colossal; LD = Labor Day; Mg = Marigoule; Ms = Marasol; Pm = Precoce Migoule and them by fertilizer treatment.

Figure 18. Total terminal growth of chestnut trees during 2019 and 2020. Data summarized by fertilizer treatment and cultivars are aggregated.

In fall 2020, the edges of leaves on trees receiving inorganic fertilizer only were noticeably brown and wilted (Figure 19). The difference in appearance was not apparent during leave expansion and growth, but only when growth ended in 2020 and leaves began to age. The difference was so consistent and obvious, that an untrained eye could determine what fertilizer treatment the tree received by simply looking at the leaves. In future years, leaf nutrient analysis may be useful for determining why leaves differed in appearance.

Figure 19. Images of leaves from Colossal chestnut trees receiving inorganic fertilizer only and organic fertilizer only in September 2020. The difference in leave appearance was so obvious that any person could look at the leaves of a tree and determine what fertilizer treatment it was given.

Pollination and nut production 2020:

Among all the trees, the average number of burs per tree was 27, the number of pollinated nuts per tree was 9, and the nuts per pound was 30. Assuming a bur could contain 3 nuts if all were pollinated, the average pollination rate was 13%. Bur count, pollination rate, and nuts per pound were variable among trees, but there were very little differences when the data were summarized according to fertilizer treatment (Figure 20).

Figure 20. Chestnut trees were treated with three different types of fertilizer – inorganic (Higgins Mix), organic (composted manure), and a mix of the two – at rates standardized by nitrogen in spring 2019 and 2020. In fall 2020, 36 Colossal chestnut trees were surveyed for the number of burs, number of pollinated nuts, and how many nuts were required to make a pound of nuts. Pollination rate was calculated assuming each bur had three potential nuts that could be pollinated.

Discussion: The results are consistent with the growth data in that very little differences were observed among treatments. From a production perspective, the pollination rate was disappointingly low, but that could be expected from a relatively young orchard where the trees are still relatively small with large spaces between trees.

Soil chemistry fall 2020:

Fertilizer treatment had major impacts on soil characteristics. The following macro and micronutrients were higher in soils treated with composted manure relative to inorganic fertilizer: pH, organic matter, nitrate, pounds of nitrogen per acre, potassium, phosphorous, calcium, magnesium, sodium, and boron. The following macro and micronutrients were higher in soils treated with inorganic fertilizer relative to composted manure: sulfate, zinc, manganese, copper, and Boron. Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was higher in soils treated with Higgins Mix, but the saturation of specific elements on the CEC varied drastically. Soils treated with Higgins mix had 65% of CEC attributed to hydrogen, whereas soils treated with composted manure had 0% attributed to hydrogen. Instead, soils treated with composted manure had nearly all CEC attributed to potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Total labile carbon did not vary substantially among fertilizer treatments. In all cases, the mixture of inorganic and composted fertilizer was intermediate to 100% inorganic and 100% organic. Soil characteristics did not vary substantially between the flat and sloped portion of the orchard if receiving the same fertilizer treatment. In other words, fertilizer treatment explained much more of differences in soils than did location of sampling. See Tables 3, 4, and 5 for average results as summarized according to field location and fertilizer treatment.

Table 3. Average soil pH, organic matter, and macro nutrients in samples collected under chestnut trees in fall 2020 after being fertilized with Higgins Mix (Inorganic), composted manure (Manure) a mix of Higgins and manure standardized according to nitrogen content in spring 2019 and 2020. Within a column, samples with different letters are significantly different.

Table 4. Average cation exchange capacity (CEC), percent saturation of elements, and active labile carbon in soil collected fall 2020 under chestnut trees after being fertilized with Higgins Mix (Inorganic), composted manure (Manure) a mix of Higgins and manure standardized according to nitrogen content in spring 2019 and 2020. Within a column, samples with different letters are significantly different.

Table 5. Average micronutrients in soil collected under chestnut trees in fall 2020 after being fertilized with Higgins Mix (Inorganic), composted manure (Manure) a mix of Higgins and manure standardized according to nitrogen content in spring 2019 and 2020. Within a column, samples with different letters are significantly different.

Discussion: Soil samples show that fertilizer treatment had major and noticeable impacts on soil characteristics that likely contributed to tree health. Applying only inorganic fertilizers on our loamy sand soils could be problematic because they did a poorer job of increasing organic matter, available nitrogen, and potassium available to trees. Even though fertilizer application rate was standardized among treatments by nitrogen content, in fall 2020, nitrogen was much higher in soils receiving manure. This is likely attributed to the soils having higher organic matter and being able to retain nitrogen at higher rates. We observed significant browning of leaves on trees receiving inorganic fertilizer only. The browning may have been a symptom of manganese toxicity caused by the interaction of low pH and high magnesium (as applied via Higgins mix). However, applying only composted manure could be problematic for chestnut production too. While composted manure improved many aspects of nutrient availability, it also increased soil pH to near 7 in our orchard. Chestnut trees can be stressed at a pH higher than 6.5. Therefore, continued application of organic fertilizer, without correction of soil pH, could also result in tree stress. If manure is to be used in future years, soil pH could be corrected by applying ammonium sulfate (21%) to supplement nitrogen.

Conclusion

- Based on these data, there is no reason not to use manure (but see #4). Young chestnut trees showed excellent growth under all three fertilizer treatments.

- Cost of organic fertilizers (manure), even when considering the additional labor to apply, was cheaper than the cost of inorganic fertilizers, as long as the cost of organic fertilizer is $0.00 because it is a waste product from on farm animal operations.

- Applying only inorganic fertilizers over many years could be problematic because of decreased soil pH, lower organic matter, available nitrogen, and potassium. Further, the interaction of low pH and high magnesium may have or may eventually result in toxicity.

- But, applying only organic fertilizers over many years could be problematic too. While organic fertilizer improved many aspects of soil health and macro and micro nutrients, it also increased soil pH to near 7 in our orchard. Chestnut trees can be stressed at pHs higher than 6.5. Therefore, continued application of organic fertilizer, without correction of soil pH, could also result in tree stress.

- Therefore, we have a case of “the goldilocks”. A mix of inorganic and organic fertilizer is what we plan to deploy in future years. In our case, we plan to move away from the Higgins mix and use soil test results to inform exactly what macro and micro-nutrients are needed.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Sunrise Cable Network produced a TV show highlighting our farm. "Let's Explore Ox Heights" was broadcast and posted on-line in October 2019.

The project and general orchard maintenance and farm operations were highlighted in 75 blog posts in 2019 and 2020 at https://oxheights.com/

This blog post in particular, highlights soil results.

The project was highlighted in a newspaper article published in the Presque Isle Advance.

A 30 minute presentation about our SARE projects was given at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Nut Producers Council in March 2019.

A field day in September 2019 in partnership with the Presque Isle Conservation District and NRCS brought 20 people to the farm.

Sunrise Communications highlighted our farm in their 1 hour+ broadcast titled "Let's Explore Ox Heights". https://vimeo.com/364787298 The Broadcast likely was viewed by thousands in Northern Michigan.

A video highlighting the project was created. https://youtu.be/_wj6lWV3Um8

Learning Outcomes

After year 1, a few lessons are emerging:

(1) Aged manure (including the labor to apply) does not cost more than inorganic fertilizer application; assuming that the cost of manure is $0.00 because it is a byproduct of on the farm animal production. Before this project, we were not sure how long it would take to apply manure around chestnuts trees and it turned out that application with a bucket was efficient and easy to replicate at each tree.

(2) Trees fertilized with aged manure on average grew as much and in many cases more than those fertilized with inorganic fertilizer. Because it can take trees 2 or more years to reflect improvements in soil health/nutrition, we expect differences among treatments may increase in future years as the experiment continues. We may request a no cost extension to continue monitoring growth and survival through years 3 and 4.

(3) Chestnut survival and growth in Northeast Michigan continues to be very high. We continue to expand our orchard and are excited about prospects in chestnut farming.