Final report for FNC19-1200

Project Information

Saturn Farms is an innovative agroforestry farm in Central Illinois. We lease the 21-acre farm via a long-term, 30-year lease developed in collaboration with Farm Commons and the Savanna Institute. Eleven acres of the farm are enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program as pollinator habitat and windbreak. The remaining ten acres are dedicated to commercial currant production.

The currant acreage contains over 18,000 currant plants, mostly black but some red and white. Integrated within the currant rows in a multi-strata agroforestry design are also hazelnuts, chestnuts, black locust, and paw paw. The trees, however, are just a few years old and will not be bearing for quite some years. All currant rows are equipped with a drip irrigation system supplied by an on-farm well.

I am currently only a part-time farmer, as the young perennial crops do not yet provide enough income to farm full-time. We live part-time in Wisconsin as a result. I grew up in the Chicago suburbs, devoid of an agricultural appreciation. It wasn’t until my undergraduate education when I realized that the problem of agriculture was central to so many modern issues, especially climate change. Since then, researching and enacting transformative solutions to the problem of agriculture has been my passion and focus.

I graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in August 2017 with a PhD in Ecology. My dissertation focused on innovative agroforestry practices, and, during my time at UIUC, I was instrumental in getting the University’s first two agroforestry research sites established. With this background, even on my farms, every tree on my farm is part of an experiment of some sort, whether via a multi-farm collaboration or just some new idea I want to test on my own.

Most shrub fruits (e.g. brambles, elderberry, blueberry, currants) are grown in rows spaced tightly (8-15 feet) to maximize yield while permitting access by mechanical harvesters. While these “alleys” receive plenty of light, their narrow width prevents efficient cultivation of most crops. Consequently, most farmers resort to a simple grass-clover groundcover, which provides neither revenue nor substantial ecological benefits to the farm.

At Saturn Farms, we also started with grass-clover alleys but have since realized the inefficiency in this approach. We wanted to explore several perennial alley alternatives that could improve farm profitability and sustainability while maintaining the management/harvest efficiency of the berries: asparagus, rhubarb, and native prairie (for seed). These are ideal alley crop candidates because their harvest seasons are complementary to most shrub fruits, and they can easily rebound after being driven over by a tractor/harvester.

We (1) established pilot plots of the three alternatives within currant alleys on our farm, (2) assessed the impact of alley crops on currant growth, yield, disease incidence, and weed pressure, (3) evaluated alley crops for compatibility with the currant machine harvester, and (4) shared findings through a field day, a video, a results bulletin, and social media.

No significant differences in berry yield or disease incidence were measured across the treatments in either year.

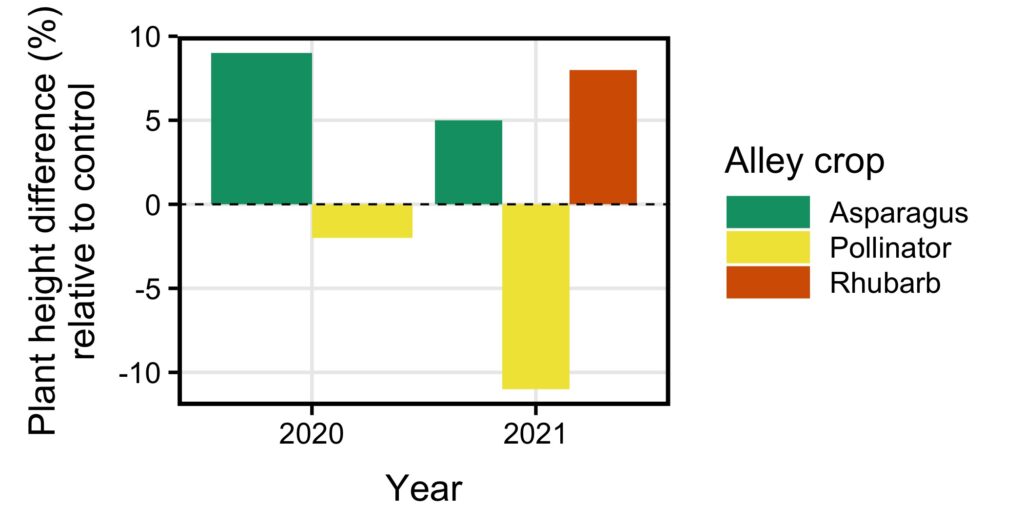

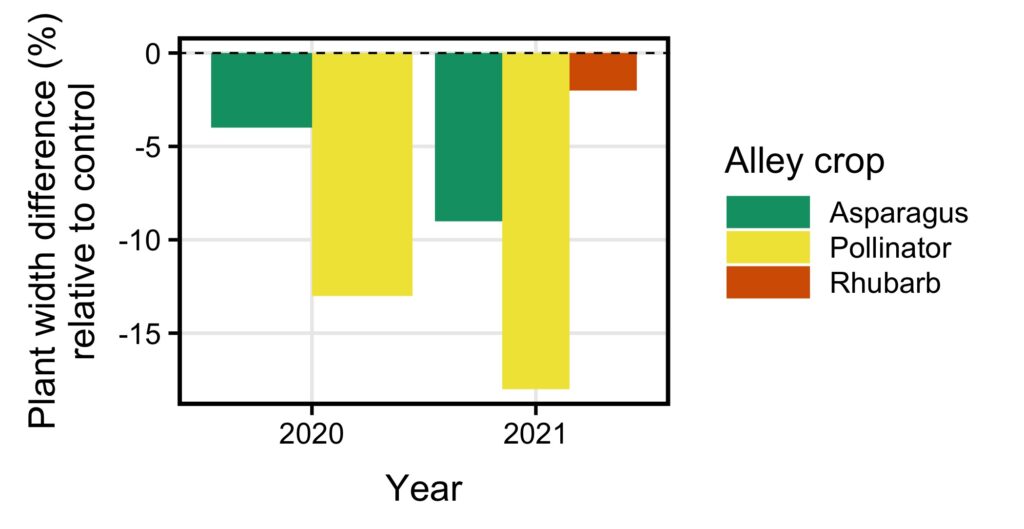

With asparagus and rhubarb alley crops, currant plant height was 5-9% greater and width was 2-9% lower relative to the control treatment. In the pollinator habitat treatment, however, while currant plant width was similarly reduced by 13-18%, plant height was also reduced by 2-11%. This reduction in plant height is most likely explained by an overall reduction in vigor in the currant plants with pollinator habitat alleys, as this treatment was the most vigorous and competitive of all the treatments.

The geometric design of both the asparagus and rhubarb treatments seemed to function as intended — good compatibility with the wheels of the tractor and harvester. However, the rhubarb was more resilient to damage caused by the low ground clearance of the mechanical harvester. The increase in currant plant height that occurred in the asparagus and rhubarb treatments may also allow the machine harvester to capture more berries as they grow higher on the stems.

1) Establish pilot plots of three perennial crop alternatives for potential use in machine-harvested berry crop alleys on our farm.

2) Assess the impact of alley crops on berry crop growth, yield, and disease incidence.

3) Evaluate the perennial crops for compatibility with the currant machine harvester.

4) Share findings through a field day, a video, a results bulletin, and social media.

Research

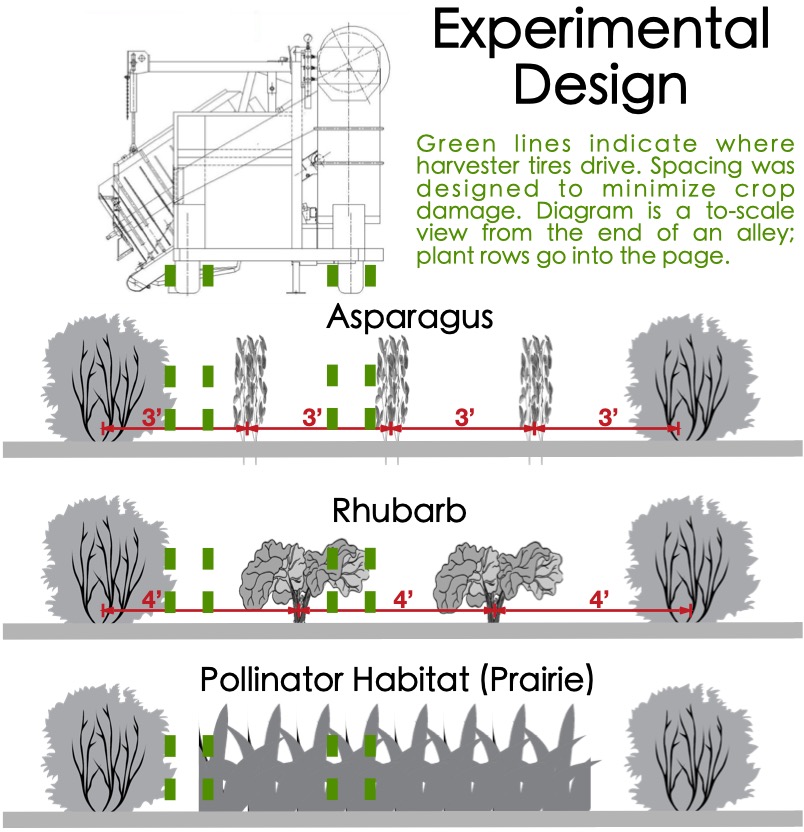

The three alley crop treatments (asparagus, rhubarb, pollinator habitat/prairie) and a control grass-clover treatment were established in plots 36-feet wide (three currant alleys) by 45-feet long. Spanning three currant alleys allowed each plot to envelope two currant rows within the treatment. Asparagus alleys contained three rows, spaced at 3-feet between rows. Rhubarb alleys contained two rows, spaced at 4-feet between rows. These configurations were based on each crop’s standard spacing, as well as compatibility with the currant machine harvester (see below). The pollinator habitat/prairie and control treatments spanned the entire alleys.

The alley crop choices of asparagus, rhubarb, and pollinator habitat/prairie were selected for several reasons. First, since most shrub fruit growers focus primarily on perennial crops, we also wanted the alley crops to be perennial. These three crops are ideal candidates because their harvest seasons are complementary to most shrub fruits, and they can easily rebound after being driven over by a tractor/harvester. Furthermore, each commands a high value in pre-existing, easy-to-access markets, so any additional marketing burden would be minimal (the potential market for the pollinator habitat is seed suppliers).

Our research methods were selected to address the three main hurdles we see preventing alley crop adoption by shrub fruit growers. Careful data collection on the alley crop impact on shrub growth, berry yield, and disease is critical to overcoming farmer doubt about the additional system complexity. Documenting and demonstrating the compatibility with the machine harvester via field days and a video maximizes the opportunity for farmers near and far to visualize and understand this complex system.

Berry Yield

Berry yield was hypothesized to decrease with the addition of alley crops due to above- and belowground competition. However, no significant differences in berry yield were measured across the treatments in either year.

Disease Incidence

Disease incidence, particularly of common foliar fungal diseases, was hypothesized to increase with the addition of alley crops due to reduced airflow. While foliar fungal diseases were found on currant plants in all treatments, no significant differences were observed across treatments. This is likely due to the high and constant winds on the farms and relatively sparse biomass of the alley crops during spring, when fungal spores are most mobile.

Plant Growth

All alley crops cast shade on the currant plants from side. Typically, this type of shading causes plants to increase vertical growth and decrease horizontal (i.e. into the shade source) growth. This phenomenon was clearly observed with both asparagus and rhubarb alley crops — currant plant height was 5-9% greater and width was 2-9% lower relative to the control treatment. In the pollinator habitat treatment, however, while currant plant width was similarly reduced by 13-18%, plant height was also reduced by 2-11%. This reduction in plant height was contrary to our hypothesis but is most likely explained by an overall reduction in vigor in the currant plants with pollinator habitat alleys, as this treatment was the most competitive. Rhubarb plots were only measured in 2021.

Harvester Compatibility

The geometric design of both the asparagus and rhubarb treatments seemed to function as intended — good compatibility with the wheels of the tractor and harvester. However, the rhubarb was more resilient to damage caused by the low ground clearance of the mechanical harvester. Taller asparagus stems frequently snapped at the base rather than bend as the harvester passed over them. It is difficult to say how this will play out in future years as the alley crops reach their mature sizes. The pollinator habitat treatment, as expected, was completely resilient to damage. The increase in currant plant height that occurred in the asparagus and rhubarb treatments may also be a long-term benefit in an unexpected way. The machine harvester is less efficient at harvesting berries that are low to the ground. By stimulating taller stems, these alley crops may also increase the proportion of berries that are higher on stems and, therefore, captured by the harvester.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

The educational video was produced in 2020 and captured the project background, alley crop designs, and experiment methods. The video

Enhancing Berry Farm Profitability with Perennial Alleycrops

now has over 2,000 views on our YouTube channel.

A results bulletin describing the project background, alley crop designs, experiment methods, and results was produced and published to our website and social media.

Saturn_AC_Exp_Results_Bulletin - Kevin Wolz FNC19-1200

Printed copies of the bulletin were also shared with field day and tour attendees.

The Savanna Institute ended up not hosting its online "Nutshell" discussions at the right time during this grant project. Instead of presenting on that platform, we opted to put more effort into giving on-farm tours to interested farmers and ag professionals.

Learning Outcomes

We learned several lessons about how to establish and manage alley crops in this new context.

In the establishment year, Central Illinois was plagued with the wettest spring on record, so planting of crowns and seed was delayed substantially until late May. Despite these non-ideal conditions, the asparagus and rhubarb treatments were successfully established. The prairie treatment was seeded, but we experienced very low germination and high weed pressure. We thought the prairie treatment should be abandoned after that year, but we nevertheless continue to mow the weeds regularly and in 2021 the prairie treatment looked quite impressive! Prairies require patience!

Regular weeding of all treatments occurred throughout the year to aid establishment. Weeding methods utilized were both hand-weeding and herbicide with a wipe-on applicator. Weeds were an ongoing problem and required more labor than originally anticipated. This was primarily because we did not have the right size equipment to mow or mulch around the alley crops. Our equipment is all setup to deal with the full 12-foot alley widths. Since this was just a pilot project, we could not justify the additional expense to purchase different sized equipment just to manage relatively small plots. But this resulted in a lot of management inefficiency!

Overall, we were very impressed that the alley crops did not impact yield or disease incidence in the currants. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen if this will continue in future years as the alley crops reach their mature size.