Final report for FNC20-1211

Project Information

Kelly's Working Well Farm (KWWF) is a small-scale, diversified educational farm. The 6-acre farm is run based on permaculture principles, and hosts a small mixed group of sheep and goats, laying hens, guinea fowl and ducks. The farm features annual vegetable gardens, hugelkultur mounds, swales, silvopasture, and mushroom production. Local food waste is delivered weekly and transformed through the addition of locally sourced wood chips into compost. Crops are planted and tended by hand; irrigation is minimal. Many fruit and nut-producing trees and shrubs have been inter-planted in swales with herbaceous perennials and wildflowers, though most of the trees are not yet bearing.

Agroforestry systems have the potential to increase both food production and environmental quality, mitigating challenges generated by climate change and land degradation. To examine whether agroforestry practices could be applied to nursery production to increase income and ecological benefits, we raised Dunstan chestnut tree seedlings in polyculture and monoculture nursery beds. We attempted to grow pawpaw trees as well, but experienced poor germination and thus evaluated only the chestnut seedlings. The seedlings in the polyculture bed were grown with a variety of annual crops including basil, zinnias, tithonia, and pole beans. We intercropped annuals to provide harvests and income while the chestnut seedlings grew to saleable size, and to study whether a polyculture design might foster mutualistic ecosystem benefits for the crops. After two growing seasons we measured root collar diameter, height, number of first order lateral roots (FOLR), and root system depth to compare seedling growth and vigor. We conducted soil tests and microbial assays to examine potential differences between the monoculture and polyculture plantings. We observed the growth of the intercropped annuals and tracked amounts harvested. KWWF hosted a series of four hands-on workshops to share our research, connect with farmers and small landowners interested in agroforestry, and teach propagation skills. Workshops included seed germination of woody and perennial plants, spring planting and seedling care, seed collection, storage and stratification, and fall planting and site preparation. Participants received hands-on instruction, free plant material, and printed handouts. The workshop series was a success, as measured by responses on participant exit surveys.

Measurements showed that the chestnut seedlings grown in monoculture exceeded those grown in polyculture for three out of the four variables examined: root collar diameter, height, and root system depth. Seedlings grown in polyculture exceeded those grown in monoculture in FOLR. Soil tests do not show substantial differences between the beds or significant change through the research period. Soil biology assays show some change in population size of individual microbial types, but the overall trends in microbes present did not change appreciably. Growing Dunstan chestnut seedlings in close proximity with annual crops in this case did not confer any obvious advantage for the tree seedlings, and only small benefits in terms of annual crops harvested.

Assess the viability of intercropping annual herbs and vegetables with chestnut seedlings in nursery production.

Build two 25’ x 4’ protected nursery beds at Kelly’s Working Well Farm.

Design and implement a program of four hands-on workshops for small landowners and beginning farmers, based on the seasonal rhythms of plants and propagation.

Promote on-farm tree nurseries and integrated farm practices.

Build KWWF nursery inventory based on Northeast Ohio’s diverse ecosystems and to mitigate challenges related to climate change and land degradation.

Generate interest in agroforestry and perennial crops within the community.

Research

To observe whether raising woody species in polyculture nursery beds with annual crops might increase income and ecological benefits, Dunstan chestnut (Castanea dentata x mollissima) seedlings were planted in two beds, one a monoculture and the other a polyculture with row-intercropping of annuals. Chestnuts were chosen for their economic potential in local markets, ecological value, and morphological habits lending potential advantages in polyculture.

I purchased Dunstan chestnut seeds from ‘Chestnut Ridge of Pike County,’ and upon receipt the seeds were bagged in moist coconut coir and placed in an unheated, attached porch for stratification. The seeds began to germinate in late February 2020, well before the soil and weather conditions would allow planting in northeast Ohio. At this point I planted them 1-2” deep in potting soil in 12” milk crates lined with screen mesh and placed them in a walk-in storage refrigerator at the Holden Arboretum, in hopes of keeping them dormant and air pruning the roots in case of vigorous growth. On March 20, due to the Covid-19 pandemic shutdowns, I removed the milk crates from the walk-in refrigerator and set them outside to wait until the soil was workable and the threat of frost past before planting them in the ground at KWWF. The seedlings were finally transplanted into prepared nursery beds in mid-May. Some were just beginning to grow up through the soil surface in the milk crates, and their roots ranged from about 2 inches up to about 6 inches deep. In the future I will stratify chestnut seeds in the refrigerator to have better control over when they germinate; the daytime temperatures on the unheated, attached porch may have been too warm and stimulated early germination. I would have preferred to keep them in the walk-in fridge until closer to planting time, but I did not know what was going to happen at that point in the pandemic. Final evaluation of the morphology of the root systems suggests that transplanting the developing seedlings from the milk crates into the ground may have had some negative impacts on root system structure. But since all the seedlings experienced the same course of events prior to transplanting, it should not negate the results of the research and the comparison of the seedlings.

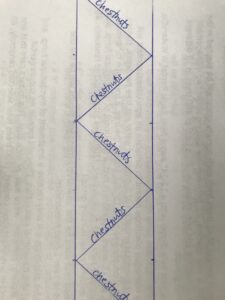

The nursery beds are situated on the edge of the vegetable garden at KWWF and receive part-shade throughout the season. They were prepared for planting by removal of aggressive ground-covers (mostly Glechoma hederacea, Mentha spp., and Fragaria spp.), and the addition of high quality compost and sand to provide 8-10 inches of loose, well-drained medium. The beds measure 25 feet by 4 feet. Tree seedlings were planted 6" apart in a zig-zag fashion, with intercropped annuals on either side in the polyculture bed (see illustration below). After planting the beds were top-dressed with wood chip mulch and protected by electric fencing to minimize predation.

Basil, Tithonia, zinnia, and pole beans were selected for market potential and lack of obvious growth habits that might hinder the tree seedlings. Seedlings of the first three crops were transplanted into the polyculture bed in mid-June 2020, and the pole beans were direct-seeded and trellised one week later. Both beds were weeded regularly and watered by hand as necessary. Observations of the crop interactions led me to change my annual plantings the following season, as the density of the plants appeared to be too high, crowding the chestnut seedlings.

Above: Bed 1, polyculture, Dunstan chesnuts interplanted with Tithonia, zinnias, basil, and pole beans, September 2020

Above: Bed 2, monoculture, Dunstan chestnut seedlings, September 2020

In January 2021, there was a power outage that affected our electric fence and we discovered that nearly all the seedlings were browsed, likely by rabbits. Both beds were equally affected, so this should not negate the results of the final comparison of the seedlings.

In early spring 2021, I added fresh compost to both beds and top-dressed with wood chip mulch. Basil was transplanted into the polyculture bed in early-June, and pole beans seeded and trellised shortly thereafter. Both beds were weeded regularly and watered by hand as necessary through the growing season.

Bed 1, Polyculture, Dunstan seedlings interplanted with basil and pole beans, September 2021

Bed 1, Polyculture, Dunstan seedlings interplanted with basil and pole beans, September 2021

Bed 2, monoculture, September 2021

Bed 2, monoculture, September 2021

To compare seedling growth and quality, I measured root collar diameter, height, FOLR (the number of first order lateral roots > 1mm diameter), and approximate root system depth. These variables were chosen after researching common nursery grading and evaluation methods, and in order to preserve the trees to be distributed and planted in 2022. I considered evaluating root to shoot ratio, but this would have meant killing the trees to achieve measurement. Morphological quality, based on examination of the physical attributes of seedlings, is commonly used to evaluate seedling quality. Height and stem diameter are the two characteristics most commonly examined on forest seedling stock, providing a good estimate of quality and subsequent field performance (Haase "Understanding Forest Seedling Quality: Measurements and Interpretation" 2008). The number of FOLR (first-order lateral roots greater than 1mm in diameter at the junction with the taproot) has been used to predict seedling growth in many studies (Gould and Harrington "Root Morphology and Growth of Bare-Root Seedlings of Oregon White Oak" 2009).

In late November 2021 I measured root collar diameter and the height of the seedlings while they were still in the ground. It took until mid-December for the seedlings to be fully dormant, at which point they were dug to observe and evaluate the root systems. The seedlings are being stored for the winter in large tubs in a mixture of moist sand, compost, and wood chips, in an unheated but very well insulated straw bale barn on the farm. They will be distributed for free in April 2022 to workshop participants and local growers.

We grew a total of 109 Dunstan chestnut trees. To compare seedling growth and quality, I measured root collar diameter, height, FOLR (the number of first order lateral roots > 1mm diameter), and approximate root system depth. The table below shows the average value of each variable for the two beds.

|

Bed 1 Polyculture |

Bed 2 Monoculture |

|

|

Average Root Collar Diameter (inches) |

0.405 |

0.508 |

|

Average Height (inches) |

21.94 |

23.52 |

|

Average FOLR (#>1mm) |

9.86 |

9.63 |

| Average Root System Depth (inches) |

11.58 |

12.28 |

|

|

The chestnut seedlings grown in monoculture exceeded those grown in polyculture for three out of the four variables examined: root collar diameter, height, and root system depth. Seedlings grown in polyculture exceeded those grown in monoculture in FOLR (the number of first order lateral roots > 1mm diameter). These results suggest that the chestnut seedlings grown in monoculture may be of higher quality than the chestnut seedlings grown in polyculture.

Despite the differences between treatments, for both Bed 1 and Bed 2, the average seedling height and caliper exceed the minimums given in the "American Standard for Nursery Stock" (2014) for Seedling Trees and Shrubs, covering plants used for forest, game refuge, erosion control, restoration, shelterbelt, or farm woodland plantings.

I conducted soil tests twice a year and soil microbial assays once each year to examine differences between the soil quality in the beds. I was curious if differences might develop over time under the two different treatments.

For the various soil tests below, Bed 1 is the polyculture planting (chestnut seedlings and various annuals), Bed 2 is the monoculture planting (just chestnut seedlings).

Soil biology assays:

Fall 2020:

Fall 2021:

Kellys Working Well Farm Report

Soil tests:

Spring 2020:

Jessica Burns-Soil-20200820-124405

Fall 2020:

Jessica Burns-Soil-20210430-133300

Spring 2021:

Jessica Burns-Soil-20211021-139520

Fall 2021:

Jessica Burns-Soil-20220111-141747

I did not identify any obvious consistent changes in soil nutrient composition over the two growing seasons. Since no attempt to amend the soil in the nursery beds was made during this project, other than the addition of compost and mulch, and to account for the nature of individual soil sample variability, I decided to average the results of the soil reports for each bed. I then analyzed the samples using "Agricola’s Best Guess v. 1.8 April 2010, The Ideal Soil Chart." After averaging the four soil tests for each treatment (Bed 1 Polyculture and Bed 2 Monoculture for Spring 2020, Fall 2020, Spring 2021, Fall 2021), it is observed that both beds follow the same general trends of excess/deficiency: excess calcium, magnesium, potassium, and iron; deficient sulfur, phosphorous, sodium, boron, copper, zinc. They both have about the same C.E.C., pH and organic matter content. Comparisons of the four cycles of soil tests looked at individually showed slight variations in variables between beds. For example, a nutrient that in Spring 2020 appeared to be higher in Bed 1 than Bed 2 might switch in Fall 2020 to be higher in Bed 2 than Bed 1, and then perhaps switch again in 2021. Soil nutrients that remained consistent (in terms of which bed had a higher value) are as follows: sulfur, sodium, manganese, copper, and aluminum were always higher in bed 2 (monoculture), while phosphorous and iron were always higher in bed 1 (polyculture). Thus it appears that Bed 1 may be lower than Bed 2 in several nutrients and trace minerals, which could potentially account for some difference in plant growth.

Soil biology assays show some change in population numbers of individual microbial type populations, but the overall trends in population dynamics did not change. Perhaps over time or at larger landscape scales soil biology would show greater differences between monoculture and polyculture planting.

I observed the growth of the intercropped annuals and tracked amounts harvested. I harvested about 25 flower bouquets and 25 bunches of basil over the 2020 growing season, as well as 6 pints of beans. The crops were distributed in weekly CSA baskets along with other farm products. The zinnias and Tithonia grew quite vigorously, crowding the chestnut seedlings; the basil and pole beans grew more modestly. In the 2021 growing season just basil and pole beans were interplanted. The basil did not grow well year; the growing conditions may have been too moist and shady. The pole beans grew well; I harvested 1.5lbs of pole bean seed in the 2021 growing season, which will be planted at KWWF in 2022. Trellising the interplanted crop gave me more control in the bed and minimized potential negative interactions between the tree seedlings and the annual crops. Growing Dunstan chestnut seedlings in close proximity with annual crops did not confer any observed advantage for the tree seedlings, though there were benefits in terms of annual crops and seeds harvested. There is still plenty of opportunity to experiment with other annual species combinations in polyculture with woody seedlings in a nursery.

One big question that this project does not address is at what scale the differences between monoculture and polyculture may become apparent. KWWF is a relatively diverse farm ecosystem, with no examples of 'monoculture' such as those seen on large scale farms focusing on a narrow range of crops. The vegetable garden where the nursery beds were situated itself is managed as a series of beds where crops are rotated annually, and every bed is typically grown as a polyculture, with both perennial crops, wildflowers and 'weeds' in proximity with familiar annual vegetables and herbs. Bed 1 and Bed 2 in this project were only four feet apart from each other, and both within four feet of other beds in the garden. So in effect, though Bed 2 was only planted with chestnut seedlings, it was situated within the context of a polyculture garden. The comparison between beds, viewed in this light, might be seen to be similar to comparing a nursery bed that was weeded with one that was not weeded.

Another factor to consider in the assessment of the chestnut seedlings is that the concept of an ideal seedling is one that evolves over time and is species specific. Depending on the project and goals of the planter, ideal seedling characteristics may very. Reforestation projects in particular, for which chestnuts are increasingly sought after, have greatly increased the diversity of nursery stock types because of the broad range of species and unique outplanting sites being managed. Seedlings that are tall at the time of outplanting tend to keep their advantage in the field over time, but in some cases tall seedlings may not be the desired target; tall seedlings can have higher transpiration rates, and may not be ideal for dry or windy sites. They may also be more difficult to plant, out of balance, and subject to wind damage (Haase 2008). Root collar diameter does typically correlate with higher survival rates, as it represents the main "plumbing line" connecting the roots and the aerial parts of a plant; it is considered the best predictor of field survival and growth. Bareroot nursery seedlings with larger root volumes tend towards higher survival in some situations, but it has been shown that up to half of the root system can be lost when digging tree seedlings, meaning that larger seedlings potentially suffer disproportionately more root loss at this time (Mexal and South Forest Regeneration Manual, Ch, 6 "Bareroot Seedling Culture" 1991). J- or L-rooting, which may have negative impacts on growth, is more prevalent when outplanting stock with long taproots. Physiology and vigor can change significantly between harvest and outplanting, even while morphology may not change much (Pinto "Morphology Targets: What Do Seedling Morphological Attributes Tell Us?" USDA Forest Service Proceedings 2011).

Having only experimented with Dunstan chestnut seedlings, there is still a lot of opportunity to examine other woody species to determine the viability of growing nursery stock in polyculture. Another variable to consider is seedling planting density.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

We did not carry out our workshop program in 2020 due to Covid-19 restrictions and local zoning issues that made it impossible to have visitors on site. In 2021 we still faced challenges related to the ongoing Covid pandemic and concurrent ongoing zoning litigation that restricted our ability to open the farm to the public. We navigated these obstacles the best we could and carried out a four-part workshop series:

March 27, 2021: Propagation of Woody and Herbaceous Perennial Plants

May 23, 2021: Spring Transplanting and Seedling Care for Woody and Herbaceous Plants in Agroforestry Systems

September 25, 2021: Seed Harvest, Storage, and Stratification for Woody and Herbaceous Plants in Agroforestry Systems

October 30, 2021: Fall Planting, Site Planning and Preparation, and Bed-Building Strategies

Advertisement for the workshops was largely done through social media and email, as well as some distribution and posting of old-fashioned flyers.

The total number of workshop attendees was 36. There were 2 small scale farmers and 2 agricultural professionals who participated in the workshops, but the majority of participants were small acreage land owners and gardeners interested in learning new skills. KWWF is situated in the greater Cleveland area, which is largely urban/suburban, with only a small percentage of the workforce engaged in agricultural activities. However, it is still valuable to expose these audiences to information about agroforestry and to teach agroforestry skills to anyone interested in learning. A successful transition towards perennial crops and agricultural resilience depends upon both producers and consumers. Getting more people in the community involved in plant propagation and cultivation is an important step towards resilience, ecosystem restoration, and food security.

At each workshop we discussed the SARE grant project and visited the beds to observe the chestnut seedlings. We made sure to credit the USDA SARE program for providing the funding and opportunity to offer the workshops at no cost to participants, and to encourage anyone interested to explore the SARE grant program as an avenue for research and experience. Once the final report is written and submitted, participants will be notified so they may read it and learn with us.

Each workshop was four hours long and began with instructors and participants sharing information about themselves, their backgrounds and reasons for attending, followed by a farm tour and a visit to the grant project beds. Next there was a presentation led by John Wright, which led into the hands-on portion of the workshop, with a break in the middle for lunch featuring locally sourced seasonal produce and ingredients.

In Propagation of Woody and Herbaceous Perennial Plants, John Wright began with a presentation detailing some of the different types of agroforestry species and types of seeds and their stratification and germination methods. We had over 20 different pre-stratified seeds available to work with that day, along with bags, containers and coir for participants to take home some seeds to attempt to germinate. We also had cuttings of elder (Sambucus canadensis), willow (Salix spp.), and red-twig dogwood (Cornus sericea) for participants to help plant out at the farm, and to take home.

In Spring Transplanting and Seedling Care for Woody and Herbaceous Plants in Agroforestry Systems, John began with a presentation covering potting soil considerations and ingredients, different types of nursery containers, bumping up seedlings, transplanting seedlings into the ground, and considerations for seedling establishment over the first several growing seasons (soil, mulching, watering, protection). We finished up by working together to prick out and pot up seedlings we grew on the farm, planting some seedlings in the farm swales, and allowing participants to pot up and take home seedlings from seeds we germinated on the farm.

In Seed Harvest, Storage, and Stratification for Woody and Herbaceous Plants in Agroforestry Systems, John began with a presentation detailing the life cycle of plants from flower to fruit, various types of seeds and fruits, tips for discerning when seeds are ready for harvest, and methods of seed cleaning/processing, storage, and stratification. Then the group took a walk across the street in a cemetery to scout for and harvest seeds; we gathered Cornus kousa, Cornus florida, Carya ovata, and Malus spp. We shared additional locally sourced seeds including Corylus americana, Asimina triloba, Panax quinquefolia, Hippophae rhamnoides, Lonicera benzoin, Castanea spp., and Prunus hortulana, among others.

In Fall Planting, Site Planning and Preparation, and Bed-Building Strategies, John covered the various considerations concerning site and species selection, and explained several strategies for building beds at home or in a farm setting. Together the group transplanted 12 Dunstan chestnut seedlings and 25 Pawpaw seedlings grown in the farm nursery into existing farm swales.

After the workshops an exit survey was sent by email to gauge how much participants may have learned, and to gather feedback. Responses indicate that virtually all respondents felt more capable and prepared to engage in propagation and cultivation on their own, and many had already begun or have plans to begin projects in the next growing season.

Learning Outcomes

Some of the biggest lessons learned in carrying out this project concern the handling of seeds and seedlings in the earliest stages of life. I stratify most seeds in unheated rooms attached to a house, due to the large volumes of seed I typically work with. However, lack of control over the environment in such a setting can lead to a mismatch between the time of germination and the ability to effectively handle the sprouting seeds. When the chestnut seeds started to germinate in mid-February, several months before I was prepared to get them in the ground, I attempted to create conditions to slow their growth by putting them into a refrigerator. Once this was no loner feasible, I had to resort to letting them grow and transplanting the seeds with developed taproots and shoots just beginning to emerge. This led to about one-third of the seedlings having J- or L-shaped root systems, observed once they were dug up in fall 2021. This root defect can cause problems later for trees. It could have been avoided if I had been able to plant the seeds before or at the moment of initial germination. In the future, I will always stratify chestnut seeds in a refrigerator, to have more control over the time of germination and to be able to plant seeds at the ideal time.

An unfortunate power outage in January 2021 led to almost all of the chestnut seedlings getting browsed. All seedlings recovered, but they have multiple shoots and I need to do more investigation to determine whether I should prune down to one shoot when transplanting the trees in 2022. I now understand better the immense importance of protecting woody seedlings at all times, to achieve the desired morphology.

I was initially quite surprised that the chestnut seedlings grown in monoculture out-performed those grown in polyculture. Perhaps this is more a testament to the challenge faced when one's beliefs and values are questioned in the light of scientific study. I find myself wanting to search for variables not previously considered to explain the difference, or ways to modify the polyculture design that could be more beneficial, or different species to try growing that might more naturally thrive in polyculture.

After working with the polyculture design, I realize there are many factors to consider when selecting appropriate species. While Tithonia and zinnias grew well, they seemed to crowd the trees too much. Basil did not compete for space as much, but also didn't grow as vigorously as it might under better ventilated and sunnier conditions. I discovered the advantage of growing a crop that can be trellised, such as beans in this case. The second season I decided to manage the beans as a seed crop, as I learned in the first season that harvesting crops from the polyculture bed was not always easy when everything was actively growing, and I risked damaging the tree seedlings and compacting the soil with my footsteps.

Having been granted the opportunity to carry out my first farm research project, I have a much better idea of the complexity involved in project design and implementation. Things I did not think about while writing the proposal now seem obvious; I experienced failures and unexpected complications every step of the way. Yet this did not discourage me; I probably learned more because of it.

In terms of what others learned from this project, the practical hands-on workshops were well-received and much appreciated by all participants. They were presented with a wealth of information on woody plant propagation, from seed harvest through transplanting, as well as various seeds and plants to grow on their own.

If asked by a farmer or rancher for a recommendation concerning polyculture nursery production, I would explain that there is a lot of opportunity for experimentation in terms of plot design, scale, and species selection. While this project did not demonstrate obvious immediate benefits to chestnut seedlings grown in polyculture with annual crops, this does not mean that other species and designs might not fare better. And despite the differences between treatments, the average seedling height and caliper in both beds exceed the minimums standards for nursery stock. Both treatments resulted in apparently healthy, quality chestnut seedlings.

I am very grateful for the opportunity to carry out this research, and to learn and share information with other farmers in the region.