Final report for FNC22-1318

Project Information

Theresa Bentz owns and operates Get Bentz Farm, in Northfield, Minnesota. Theresa raises Icelandic sheep for wool and meat production locally. Get Bentz Farm sits on 40 acres of pastures and woods, and 5 acres of hay production. The land supports 40 breeding sheep and their spring/summer lambs. The Bentz farm recently invested in wool milling equipment and processes fibers from her farm and other local farms, adding value and opportunities for wool milling that is currently limited due to lack of mills. Beginning in 2021, Theresa partnered with Alejandra Sanchez to offer natural dye classes on the farm, and grew a small garden of dye plants on an open acre of land. Theresa is past president of the Cannon River Sustainable Farming Association chapter and sat on the board of A Greener Pastures. She is active with the Minnesota Farmers Union. Theresa recently worked on a research project with Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships to understand Minnesota’s wool economy.

Maddy Bartsch has been cultivating natural dye plants for the past 6 years, growing up to 30 species of dye-producing plants at 3 different gardens throughout the metro. Their natural dye business, Salt of the North Dyes, received guidance from Augsburg University’s MBA Project Management course resulting in a full business plan (report can be provided upon request). Maddy's previous experience in farming and textile systems includes project management for the Minnesota Hemp Wool Project and the Three Rivers Fibershed Regional Fiber Sourcebook, as a research assistant for the National Mill Inventory Survey, as a Farm Educator at Gale Woods Farm and as one of Fibershed’s ‘Yarn Incubators’. Maddy is also the Community Connector for the Cannon River chapter of the Sustainable Farming Association. Maddy teaches textile classes to learners of all ages throughout the Midwest, grows natural dye plants and products for sale, creates curriculum on dyes, and is deeply immersed in Minnesota’s textile community.

Reliance on petroleum-based synthetic dyes has led to devastating impacts on our air, water, and soil. Natural dyes have the capacity to create a beneficial impact on the environment while offering economic opportunities to increase profitability for farmers and meet the growing demand of conscious consumers. With few natural dye retailers in existence and the majority of natural dye production occurring outside the country, our project will develop methods of dye plant production for farmers in Zone 4. This will increase profitability for farmers who already grow species that can double as dye plants, while utilizing unused areas to incorporate pollinator and soil friendly plants that yield dye pigment. By identifying dye plants that are best suited for our climate, we can offer research-based guidance to farmers of the potential value-add that including dye plant crops as part of their rotation can have on their overall operation. Through measuring yields, comparing growing techniques, and studying available markets for dye plant products, we will be able to provide education for farmers and community members and increase access for eco-conscious consumers.

- Identify dye plants that perform well in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 4.

- Identify preferred production methods to increase dye plant harvest, yield, and pigment saturation.

- Evaluate the added value of using dye plants to increase market opportunities for farmers.

- Documentation of the project via social media (Instagram) to spread awareness.

- Share findings through field days, natural dye classes, conferences/events, and through relevant fiber and farming organizations in the area (SFA etc.).

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

Research

Growing Season - 2022

Dye seeds were purchased in March and grown in Open Hands Farm’s greenhouse. The soil that Open Hands Farm, along with other organic farms in the area, started the plants in lacked proper nutrients (specifically Nitrogen) so plant growth was stunted and we had poor germination rates. In April we reseeded a number of varieties due to low germination and added nutrient amendments provided by the soil company.

Plot preparation began in mid-May. Having previously been a grassy field, we enlisted the draft horses from Burning Daylight Draft Farm to do the bulk of the tilling and disking.

Open Hands Farm and Little Hill Berry Farm used their tractors to finish preparing the land. The final dimensions of the tilled area were about 70’ x 70’. We began the process of adding drip irrigation, weed suppression methods (mulch and landscape fabric), and cover crops (a mix of buckwheat, field peas, white Dutch clover, rye grass).

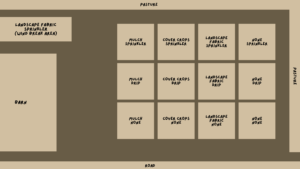

With the slow start to our seedlings, all dye seedlings were planted in the ground by mid-June. Dye species were grown on a 1/8 of an acre in four sections: mulch, cover crop, landscape fabric, and no weed suppression or soil cover. Within each section there were three types of irrigation tested: sprinkler, drip, and no irrigation. Below is a general map of how we organized the field:

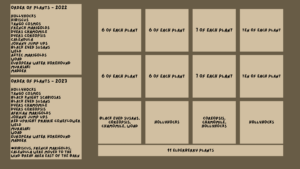

Crops grown included: Madder, Coreopsis, Weld, Chamomile, European Water Horehound, Murasaki, Tango Cosmos, French Marigold, African Marigold, Black Eyed Susan, Double Black Hollyhocks, Calendula, Zinger Hibiscus, Johnny Jump ups, and Woad. The diagram below explains the number and order of crops grown:

We've included a list of the general colors achieved by each type of plant alongside photos showing the results we achieved on wool and cotton fibers.

- Madder (red)

- Coreopsis (burnt orange)

- Weld (yellow)

- Chamomile (yellow)

- European Water Horehound (black, grey brown)

- Murasaki (purple)

- Tango Cosmos (orange)

- French Marigold (orange)

- African Marigold (orange)

- Black Eyed Susans (green)

- Double Black Hollyhocks (purple)

- Calendula (orange)

- Zinger Hibiscus (red)

- Johnny Jump ups (blue/purple imprints)

- Woad (blue)

Harvesting of dye material began in mid-July. Detailed recordings were made to identify what irrigation and weed suppression methods were used, along with the total weight of dye stuff harvested in ounces, and the date of the harvest. Simultaneously, we created an email address ([email protected]) and a newsletter list to update interested individuals which grew to 48 individuals in 2022 and to 88 individuals in 2023.

With the majority of dye plants in bloom by August, we hosted three u-pick events which attracted artists, designers, herbalists, crafters ranging in age from high school students to older adults in their 70s.

By August, we were harvesting so many flowers that we teamed up with Trinity Muller, owner of Petal and Hank (a local natural dye business), to dry our dye stuff and conduct experiments with the flowers. Below is a photo Trinity took of sample skeins she created from plants in the dye garden.

Harvesting and garden upkeep continued through the beginning of October, with work days twice a week to harvest, observe, and maintain the plot.

Growing Season - 2023

Due to the warmer spring, we were able to get into the ground in late April and transplant a number of the perennial hollyhock plants to give them more space to grow. They were originally planted too close to each other and Maddy worried they would end up with leaf rust once they grew. Transplanted plants largely survived and produced flowers, albeit less than their counterparts that were not transplanted (hollyhocks do not like having their roots bothered so that was to be expected). Seeds were started at Open Hands Farm in their greenhouse in April with the first batch of seedlings ready for planting by early May, and the second batch ready at the end of May.

In mid-May we spread two cover crop blends from Albert Lea Seed (Organic Plowdown Blend CC9 Cover Crop Mix and Organic Graze & Chop Forage Mix) to test weed suppression in one quarter of the growing area. The cover crop grew quickly and held weeds at bay, especially in the lower half of the field (right side of photo) where it received adequate irrigation. Unfortunately, due to the slope of the land and lack of rain, the weeds over took much of the cover crop in the top half of the field (left side of photo).

Irrigation continued to be a challenge throughout the summer as the drip we had installed was not consistent across the entire line, which cost us a number of plants throughout the areas relying on drip irrigation. We found the sprinklers to be a more effective way to water the large areas we were growing, with on and off timers to control days/times they were on, but more susceptible to the strong winds that blow through the field most days. This made knowing where to position the sprinklers difficult and dependent on the amount of wind on a given day.

As the summer progressed, we offered weekly U-pick nights starting on June 21st. Our hours were 4 p.m. to sunset all growing season, with the last U-pick night on October 14th. Due to feedback about participants not being able to come on a weeknight, we also hosted four Saturday U-pick events to accommodate more schedules. Visitors were invited to come to the farm, learn about the project, and guided into the field to harvest their preferred dye stuff. After harvesting, participants came into the barn and weighed, recorded and paid for their dye stuff according to a sliding scale of $4 - $10 per ounce harvested. Total amount earned from U-pick nights was $1,031. All ages were present at U-pick nights from children with their families to older adults, and very few repeat groups (or in other words, there were almost always new visitors at U-pick nights). Visitors included artists, crafters, dyers, shepherds, curious locals and those familiar with the project.

Petal and Hank enlisted family members to grow their flowers this season so we decided to dehydrate the flowers on the farm. We utilized box fans over simple drying frames (wooden frames with window screens stapled to them) for most dye stuff. We used dehydrators for the species of flowers that held more moisture and needed to be thoroughly dried in order not to mold, like marigolds. Using low heat (max of 125 degrees) over a long period of time (up to 30 hours) worked best to ensure dried dye stuff could be put in glass, paper or cloth bags for indefinite storage without mold or pest issues.

In addition to markets, Theresa and Maddy offered multiple classes throughout the metro and beyond incorporating flowers from the garden in their courses. In order to use up excess pigment, Maddy also began making paints and pigments from the left over dye vats. This may be an area to look into for future sales and storage of dye pigment (powdered).

Harvest results

All weights in the charts represent the fresh harvest weight. Below are the results from the 2022 and 2023 growing season:

| Species | Total harvested in ounces (2022) | Weight in pounds | Total harvested in ounces (2023) | Weight in pounds |

| Weld | 415.89 | 26 | 7.55 | 0.47 |

| European Water Horehound | 9.6 | 0.6 | - | - |

| Zinger Hibiscus | 0.39 | 0.024 | 33.34 | 2.1 |

| Woad | 353.36 | 22.1 | 32.97 | 2 |

| African Marigolds | 98.16 | 6.13 | 693.81 | 43.3 |

| French Marigolds | 366.55 | 23 | 446.823 | 28 |

| Aztec Marigolds | 148.87 | 9.3 | - | - |

| Marigolds | 230.75 | 14.42 | - | - |

| Johnny Jump ups | 6.65 | 0.42 | 11.46 | 0.72 |

| Chamomile | 138.49 | 8.7 | 587.64 | 36.72 |

| Black Eyed Susans | 530.49 | 33.1 | 109.1 | 6.8 |

| Calendula | 248.83 | 15.5 | 82.06 | 5.13 |

| Coreopsis | 154.95 | 9.7 | 22.82 | 1.4 |

| Cosmos | 151.03 | 9.4 | 71.876 | 4.5 |

| Eucalyptus* | - | - | 128.76 | 8 |

| Madder** | - | - | 89.21 | 5.6 |

| Hollyhocks** | - | - | 370.12 | 23.13 |

| Scabiosa* | - | - | 71.84 | 4.49 |

| Red Upright Prairie Coneflower* | - | - | 94.47 | 5.9 |

|

Totals |

2854.01 | 178.394 | 2853.849 | 178.26 |

|

* denotes new varieties trialed in 2023 **denotes species not ready for harvest until second year ***a number of dye plants require multiple years to produce color such as Double Black Hollyhocks, Madder, Murasaki, European Water Horehound, so yields are not reflected in the first or second year records. Murasaki and European Water Horehound will be harvested in spring 2024. By working with Petal and Hank, we determined that fresh to dry harvest conversions averaged 25% of the fresh harvest weight. |

||||

Survival rates of perennial plants

The table below reflects the number of perennial plants that survived from one growing season to the other.

| Perennial plants that survived the winter | |

| Plant species | # of plants |

| Black Eyed Susans | 10 |

| Hollyhocks | 43 |

| European Water Horehound | 23 |

| Woad | 40 |

| Murasaki | 11 |

| Madder | 32 |

| Chamomile | 41 |

| Johnny Jump ups | 15 |

Observations

-The 2023 weld crop did not go to flower in the first year like it did in 2022's growing season. This is to be expected as weld is considered a biennial with the first year growing a large rosette and going to flower in the second year. 2023's results reflected the two year timeline whereas 2022's results were unusual.

-Zinger hibiscus was moved alongside the pole barn to give the plants a bit of a wind break, which resulted in healthier plants and a larger harvest. The plants did not tolerate the constant wind as well as other species and put most of their energy into growing thick stalks.

-We grew less calendula in 2023 as it has less pigment than other plants that also produce yellow dye.

-We did not grow Aztec marigolds in 2023 and focused on French and African varieties instead.

-Our woad plants went to seed in 2023, as they are a biennial. We collected seeds and removed the 2nd year plants (this is important because woad plants spread easily and can take over an area if left untended). In addition to seed saving, we found the woad seeds to yield a blue/green color and offered them as a dye stuff for sale.

-Perennial plants like madder and double black hollyhocks were finally able to be harvested. Other perennial plants like dyers chamomile had a tremendous year and produced abundantly. This was echoed by other growers who shared that it was a banner year for their dyers chamomile plants.

-We lost most of our black eyed susan from the 2022 growing season and the seedlings we planted in 2023 did not grow as robustly as they did in the 2022 growing season resulting in a lower harvest amount.

-Based on feedback and interest from visitors in 2022, we added eucalyptus, black knight scabiosa and red upright prairie coneflower to provide more options of plants that produce blue, purple, and green dyes.

-Eucalyptus, calendula, and French marigolds were moved alongside the barn near the area where we planted the hibiscus. This was to see if they also fared better due to the windbreak.

Other Revenue Sources

During the 2023 growing season, we sold dye plant seedlings on a sliding scale of $3.50 - $8 per plant. With a first-come-first-serve method and a set number of extra plants available, we didn't know how many or what species people would be interested in. This chart details the varieties and quantities we sold:

| Species | Beginning # of seedlings | Remaining # of seedlings |

| Woad | 63 | 15 |

| Japanese Indigo | 88 | 30 |

| Red Upright Prairie Coneflower | 48 | 5 |

| European Water Horehound | 29 | 0 |

| Dyer's Coreopsis | 29 | 3 |

| Dyer's Chamomile | 19 | 7 |

| Tango Cosmos | 24 | 7 |

| Black Eyed Susans | 24 | 0 |

| Weld | 40 | 15 |

| Black Knight Scabiosas | 23 | 0 |

| Double Black Hollyhocks | 24 | 0 |

| Murasaki | 18 | 0 |

| Madder | 30 | 0 |

| Greenthread | 24 | 0 |

| African Marigolds | 24 | 0 |

| Total | 507 | 82 |

Total sales from seedlings was $1,263.00 resulting in an average of $3/per plant sold. We will continue to grow extra seedlings for spring sales going forward. Due to the unique nature of the species of plants used in natural dyeing, we found that we were often the only people in the area selling the specific species of plants, giving us a competitive edge.

With a better handle on the overall flow of growing for 2023, we decided to sell more of the dry dye stuff off the farm. Theresa and Maddy attended seven markets throughout the summer including the Mill City Farmers Market, Minnesota Fiber Festival, Yarnover, and the Fall Fiber Festival, offering dried dye stuff and dye kits. Dried dye stuff was sold along a sliding scale of $6 - $10 an ounce with the most sought after plants selling out quickly. These were generally plants that produce blues, purples, greens, and reds. Customers told us these were the colors they didn't have in their own gardens or collections and wanted to try out. Plants that produce yellow and orange received the least amount of interest, as they are more common in the natural dye world. The kits we sold included dried dyes, yarn for dyeing, instructions and a mordant to adhere the color to the yarn. Kits were a popular offering for those just getting started or hearing about natural dyeing for the first time. Total sales of dried dye stuff and kits came to $2,084.

At the end of the 2023 growing season, we began exploring selling wholesale to established organizations like Botanical Colors and Green Matters Natural Dye Company that either sell DTC or use natural dyes in their work. We feel a combination of wholesale accounts and retail accounts or DTC will provide a better balance that requires less time marketing our products so we can focus on farming.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

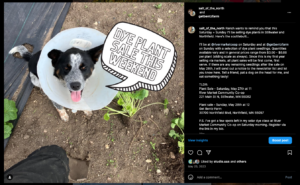

On-farm demonstrations, tours, and field days occurred throughout the summer as U-pick nights, mill tours, and special one-on-one visits with interested parties. We advertised U-pick nights, tours, and open farm days via the Get Bentz and Midwest Dye Coop newsletter, via Theresa and Maddy's Instagram accounts, with flyers at farmers markets such as the Mill City Farmers Market and fiber festivals throughout Minnesota.

Below are examples of posters and hand outs given out at farmers markets. Maddy and Theresa also brought the fliers to hand out after they taught classes off the farm.

The published press article was from March when the project was featured in The Land magazine's cover story. Below is a link to the article.

We also added a page to the Get Bentz Farm website that talks about the project and will be updated with a link to the complete report.

We want to continue connecting with our growing audience of interested individuals through newsletters, events on the farm, creating zines about the plants and their dyes, and teaching classes that build on the work we've done.

Learning Outcomes

Reflections from the 2022 Growing Season

Dye plants like Johnny Jump Ups were too difficult to harvest and dry. Zinger Hibiscus began blooming right before the first frost, which killed every plant. In order for this plant to be considered in our climate, they would need to be in a hoop house or covered.

The process for determining when woad is ready for harvest was more difficult than expected. We need more clarity about this in order to advise others.

The land was not leveled before laying out our drip irrigation, resulting in uneven water flow across the plot. This was notable during the first few weeks of summer when we had very dry conditions.

The mulch used for weed management could have been about 2" deeper to better suppress weeds.

Hawk moth caterpillars were found among Madder plants eating all the foliage, otherwise, the plants endured relatively low pressure from pests. Other pests seen included Japanese Beetles which would eat the leafy foliage of the hollyhocks.

Most common weeds causing pressure are Canada thistle, pigweed, quackgrass, quickweed, velvetleaf, dandelions, crabgrass, creeping charlie, lamb's quarter, and smartweed. In addition to wood mulch and landscape fabric, waste wool was tested along one edge of the perimeter of the plot. We found the wool mulch to be quite effective in suppressing weeds, maintaining moisture, and breaking down slowly.

We are paying attention to the plants in the mulch section, which struggled compared to the other areas. This may have been due to the wood chips leaching nitrogen, as the most effected plants seem to be nitrogen sensitive.

The plot took a long time to get up and running but by the end of July/beginning of August my 2 times a week visits were not enough to stay ahead of the harvests. For 2023 we are planning to increase harvesting to 3 days a week with the intention to do a full harvest each time. In late summer there was little time for weeding by hand with a hoe and some areas became overgrown (mainly the test area with no weed suppression).

We want to find a better way to record harvests and will work on a handout for people who come to our U-pick with what to do with the dyes next.

We noticed a wide variety of native pollinators drawn in by the flowers, many new to the farm like dragonflies.

Reflections from 2023 Growing Season

To address the issues with irrigation that resulted in plant loss, we will be switching from a soaker hose to flat drip tape and changing the orientation of the field to use the slope of the hill (which will run east to west). The current layout of the irrigation runs north to south across the field.

Harvesting and weeding remain the most time intensive parts. Some options I'm looking at to increase efficiency:

-Changing the way I grow madder and other root plants. Because the pigment is in the plant's roots and needs to be dug up, it makes the process of harvesting them a time-intensive scavenger hunt. For 2024 I plan to grow madder in fabric grow pots to make removal of the roots easier on me.

-For 2024 we are looking at more trellising, cages, etc to make deadheading of plants quicker and introduce tools like hand rakes and tea leaf trimmers that can make harvesting less time intensive.

-Weeding was a continual drain on my time and took me away from harvesting. While necessary so the dye plants could access water, sun, and have space to grow, flowers got away from me because of a lack of time to harvest. In areas where we let the weeds grow, the dye plants became easily lost or choked out by other dye plants that were more established. The areas that had landscape fabric were easy to harvest and made weeding simple, but they increased temperatures and seemed to trap some of the plants from growing. I plan to switch to a heavy duty paper landscape fabric from Fedco to provide suppression without added heat and permeable barrier for water and air.

Plants I will continue to grow will largely be plants that produce blues, purples, reds, oranges, or greens as those are the most sought after colors by dyers and artists. Because yellow is such a common dye plant color, the plants that produce yellow don't sell as well. Customers are generally looking for a color they don't have in their own garden or collection. This year we also connected with one of the local college's anthropology department, as they were very interested in the woad we were growing. We plan to continue collaborating with the college's anthropology department to better understand how to time the harvesting and processing of woad.

We are looking at investing in a hoop house to extend our growing season and by extension, increase the amount we can harvest in a given season.

Finally, our next steps include prototyping a wool felt mulch that can act as a compostable weed barrier around perennial plants and fine tuning markets before we engage additional farmers to also dye plants on their land for pooling purposes. We've been able to gain a lot of knowledge and practical information through this project and we're eager to share it with others and move closer to a cooperative venture of dye plant growers.