Final report for FNC24-1420

Project Information

The Johnson’s are a first generation farming family with 5 kids, ages 7-15. Our 180-acre farm, Ox Heights, is in Presque Isle County Michigan (NE lower peninsula) and is certified in the Michigan Agriculture Environmental Assurance Program in Farmstead Systems, Cropping, Livestock, and Forest, Wetlands, and Habitat Systems. With support from SARE (Projects FNC17-1081, FNC19-1170, FNC21-1329), USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and our family, we are learning and demonstrating how farmland on marginal loamy sand soils in the North Central Region can grow sustainable, high value, and diverse crops. We maintain 20 ewes that produce ~35 lambs for meat annually. The sheep are rotationally grazed through our 30 acres of grafted European chestnuts (SARE FNC17-1081 and FNC19-1170) and English Walnut/Peach intercrop orchard (SARE FNC21-1329). Hay for the winters is taken from about 10 acres. Our remaining acreage is managed for Christmas greenery and timber products. Abby (proposal leader) has an Engineering Degree from Michigan State University (Biosystems Engineering) and is President of the Midwest Chestnut Producers Council. Nick (Husband) has undergraduate and graduate degrees in Fisheries, Wildlife, and Forestry. In this project, we converted approximately 5 acres of our 10-acre hay field into an intercropped, silvopastured pine nut plantation to test establishment practices for Korean Pine and Siberian Pine.

Edible pine nuts are a nutritious high value crop that, once established, grows well on sandy soils in climate zones 3 or greater. Therefore, pine nuts could be a crop farmers in the North Central Region could use to diversify revenue, sequester carbon, a establish a multi-generational permanent crop. Pine nut trees native to Asia, like Korean Pine and Siberian Pine, have been established in the North Central Region because there are no pine trees native to our area that produce nuts large enough to market for human consumption. Unfortunately, in our personal experience and that of others, Korean Pine and Siberian Pine trees have be difficult to establish after transplanting. Because Korean and Siberian Pine trees are not native to North America, some hypothesize that the symbiotic microbial environment they need to thrive is not naturally present in North American soils and the lack of symbiotic microorganisms can limit establishment success. Others hypothesize that these pine trees need protection from wind and direct sunlight to during establishment. Therefore, we conducted an experiment to better understand best practices for pine nut tree establishment in the North Central Region by documenting establishment success of bare root Korean and Siberian Pine trees given varying microorganism inoculate treatments and tree shelter treatments and compared establishment success to native fir trees.

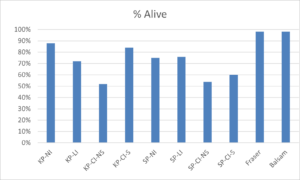

In the absence of any inoculate or shelter treatments, native fir trees exhibited the highest survival rates (98%), with Korean pine (88%) and Siberian pine (75%) being significantly lower that fir, but not significantly different from each other. Unexpectedly, commercial inoculation consistently was associated with reduced survival in both pine species, whereas shelters substantially mitigated this effect in Korean Pine but not in Siberian Pine. Regardless of treatment, surviving Korean and Siberian pine grew slowly. Average growth over two growing seasons was 1-3 inches, with inoculate or shelter treatments not explaining any of the variability in growth. Our experiment provides clear evidence that Korean and Siberian Pine are more difficult to establish than native fir trees and grow slowly after the first two years of establishment. The experiment unfortunately did not find any "silver bullet" for improving establishment success or growth after establishment; inoculate treatments nor shelter treatments produced higher survival and growth than the negative control (no inoculate and shelter).

Accordingly, this experiment provides no evidence that inoculant or shelters are worth the extra work and expense on our farm when planting bare root trees. Instead, we think it may be worth testing the establishment success of potted Korean and Siberian pine as means to minimize disturbance to the roots and any microbial communities associated with them . We also would like to see more nurseries in the North Central Region offering these pine trees. We had difficulty procuring Korean and Siberian Pine from a U.S. source and therefore needed to import our bare root pine trees from Ontario. The Ontario provider did everything in their power to expedite shipping, but shipping still took 7 days due to customs inspection. Therefore, we think it would be a great service to farmers in the North Central Region if more nurseries provided potted Korean and Siberian Pines because these trees would be highly preferred to purchase when we want to establish more.

Objective: Determine how survival and growth of transplanted pine nut trees vary with soil inoculate treatment and tree shelter use.

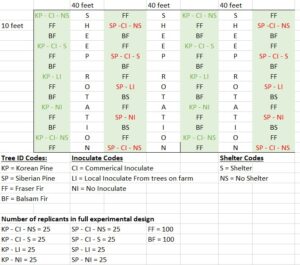

Solution: We investigated what establishment tactics produced the highest survival and growth rates for two species of pine that produce edible nuts in the North Central Region. We conducted the experiment on two types of trees that produce large edible pine nuts and are hardy to Zone 3, Korean Pine and Siberian Pine. We varied inoculate treatments and tree shelter treatments. The inoculate treatments included (1) commercially available inoculate (https://www.nuttrees.com/edible-nut-trees/edible-pine-nut-trees), (2) inoculating with soil collected from under existing Korean Pine trees on our property, and (3) no inoculate. Inoculate from existing trees were introduced by collecting 1 cup of dirt from under our 6-year old Korean pines and placing the soil in the planting hole. The tree shelter treatments were a modified tree shelter for evergreens that we constructed from mesh material. The tree shelter provided shade and protection from wind, without producing the heat and confined conditions of a typical plastic tree tube. Therefore, the experimental design was a 2 x 3 x 2 factorial design (2 tree species, 3 inoculate treatments, 2 tree shelter treatments) with the following number of replicates per treatment: 100 Korean pine; 50 with commercial inoculate, 25 with inoculate from existing Korean Pine trees, and 25 with no inoculate. Of the 50 with commercial inoculate, 25 were a tree shelter and 25 were in a tree shelter. The same number of Siberian pine trees were planted with the same experimental treatment strategy. Treatments were systematically assigned throughout the planting field to minimize bias or artifacts from planting location. Pine nut trees were planted at a 35 foot by 40 foot spacing with drip irrigation provided. As a control, two conifer trees native to North America were planted between the pine nut trees, namely Fraser fir and balsam fir, so survival and growth of an industry standard conifer tree in the North Central Region can be compared to the pine nut trees. Fraser and balsam fir are also a good companion crop for pine nut trees because they can be harvested after 10 years for the wreath or Christmas tree industry as the pine nut trees are maturing. Fir trees were planted with no inoculate or shelters applied. The experiment occurred on a field with marginal hay production and loamy sand soils; a circumstance common on many farms in the Midwest that are on glacial till deposits. Soil tests occurred at the beginning and end of the experiment. Potash was applied to the field prior to establishment. Sheep were grazed in the aisles of the planting (35 ft spacing) to keep the land in production and soil nutrients cycling while the trees are establishing. Results were communicated through our website, our social media feeds, a conference presentation at the 8th Annual Underground Innovations Meeting, and a final report to SARE.

Illustration of experimental design and planting plan for pine nut trees under different inoculate and tree shelter treatments.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

Research

286 Fraser fir and 284 balsam fir were picked up directly from Northern Pines Nursery in Lake City, MI, on April 12th, 2024, which is about 100 miles from our farm. The trees were 2-year old and termed p+2 in their catalog. Fir trees were hand planted by April 17th, 2024, as described at this link at Ox Height's Blog.

Kids planting trees

On April 16th, 2024, local mycorrhizae inoculate was procured from established Korean Pine trees on our farm (Ox Heights) by harvesting dirt that was in contact with the root systems of the Korean Pine. Local inoculate was stored in our barn basement at ambient temperature until used later that month.

100 Siberian and 100 Korean Pines were delivered from Rhora's Nut Nursery on April 22nd, 2024, and were hand planted by April 30th, 2024, as described at the Ox Heights Blog and in this video. Trees were shipped from Rhora's because they are about 600 miles from our farm. Commercial inoculant and local inoculate (harvested from our Korean pine trees) was added to the holes as described in this video. The pines were shipped from Rhora's on April 16th, 2024. The trees were in transport for about a week and had about 0.5 inch of new growth upon delivery to Ox Heights. Whether new growth occurred prior to shipping or during shipping is not known. The root systems of the Asian pines were small compared to the fir trees.

Korean and Siberian Pines Arrive from Rhora's Nursery on 22April2024

Tree shelters were constructed around Korean Pine and Siberian Pine assigned to have tree shelters as described in this video.

During May 2024, tree height and trunk diameter were documented for each Asian pine tree planted.

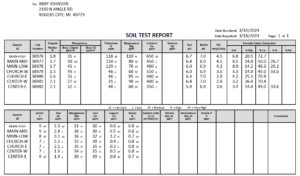

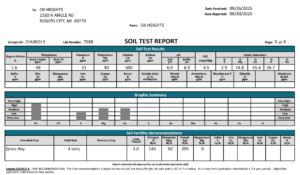

A soil test on the pine nut plantation site was taken March 2024. Results showed a deficiency in potassium, so as proposed, two tablespoons of potash was provided to each tree in the study during May 2024.

Drip irrigation was supplied to all trees planted immediately after planting. Specifically, we used 1 gallon per hour drippers and provided water once per week for 2 hours each week rain was not greater than 0.5 inches. Weeds around planted trees were controlled using foliar spray glyphosate in early June. Later in the summer, weeds near each tree were removed by hand.

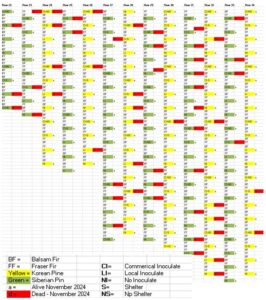

During November 2024, which was after one growing season, each tree was assessed to determine if it was alive or dead where dead trees were completely brown or shed all their needles. During September 2025, which was after two growing seasons, each tree was assessed to determine if it was alive or dead. If the tree was alive, tree height and trunk diameter were documented using the same approach as we did in May 2024. Furthermore, we assessed the color of the pine needles as an overall indicator of health and vigor where a score of 1 = dark green, 2 = green, 3= yellow green, 4= brown yellow.

Analysis: Survival by species, inoculate treatment, and shelter treatment

Survival was recorded as the number of trees alive or dead at the end of the September 2025 for each species × treatment combination. Survival proportions are reported as percentages. Survival was treated as a binomial response (alive vs. dead). Analyses were conducted using contingency table methods based on aggregated counts. Because sample sizes per treatment were modest (approximately 24–26 seedlings per group), two-sided Fisher’s exact tests were used for all pairwise comparisons.

Species effects were evaluated by comparing Korean and Siberian pine survival under control conditions (no inoculant, no shelter). Inoculant effects were assessed separately within each species using pairwise comparisons among control (no inoculant), local inoculant, and commercial inoculant treatments under no-shelter conditions. Shelter effects were evaluated only within the commercial inoculant treatment, as shelters were not applied to other inoculant levels. All tests were conducted at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Analysis: Growth and condition by species (Korean Pine and Siberian Pine), inoculate treatment, and shelter treatment

We evaluated whether percent change in height, percent change in diameter, and green color rating varied among species, inoculant, and shelter treatments in September 2025 using factorial linear models. Percent change was calculated as ending measurement divided by beginning measurement to standardize growth metrics by starting tree size. Each response variable was analyzed separately with species, inoculant, shelter, and their interactions as fixed effects. Model assumptions were met as assessed using residual diagnostics.

Data release for all raw data collected during our SARE Funded Pine Nut establishment Project.

Observations after one growing season (April 2024-October 2024)

Korean and Siberian pine trees averaged about 15 inches in height and 6 mm in diameter when planted. Survival of Korean and Siberian Pine aggregated across all treatments their first year averaged 75% with no substantive difference in survival between the species. Survival of Fraser fir and balsam fir were 99% and also averaged 15 inches tall when planted.

| Species | Number Planted | Number Alive | Number Dead | % Survival | Initial Height (inches) | Initial Diameter (mm) |

| Korean Pine | 100 | 77 | 23 | 77% | 16.4 | 6.4 |

| Siberian Pine | 100 | 72 | 28 | 72% | 14.8 | 5.9 |

Korean and Siberian pine trees that were sheltered had slightly higher survival in their first year than those that were not sheltered, but differences were marginal.

| Shelter | Number Planted | Number Alive | Number Dead | % Survival | Initial Height (inches) | Initial Diameter (mm) |

| None | 150 | 110 | 40 | 73% | 15.8 | 6.3 |

| Shelter | 50 | 39 | 11 | 78% | 14.9 | 5.7 |

Survival of Korean and Siberian pine receiving no inoculate survived at higher rates in their first year than those receiving local inoculant or commercial inoculate.

| Inoculant | Number Planted | Number Alive | Number Dead | % Survival | Initial Height (inches) | Initial Diameter (mm) |

| Commercial | 101 | 71 | 30 | 70% | 15.6 | 6.1 |

| Local | 50 | 38 | 12 | 76% | 16.2 | 6.3 |

| None | 49 | 40 | 9 | 82% | 15.0 | 6.1 |

Initial size of the Korean or Siberian pine did not generally correspond to higher survival during their first year.

| Korean Pine | Number | Initial Height | Initial diameter |

| Alive | 77 | 16.6 | 6.5 |

| Dead | 23 | 15.8 | 6.0 |

| Siberian Pine | Number | Initial Height | Initial diameter |

| Alive | 72 | 14.7 | 5.9 |

| Dead | 28 | 15.1 | 5.9 |

Taken together, there was no obvious variable that explained survival during the first year. For Korean Pine, highest survival was with trees planted with no inoculate and provided no shelter. For Siberian Pine, highest survival was with trees provided local inoculate and no shelter. Both Korean Pine and Siberian Pine showed very little overall new terminal growth during their first year (~roughly 1 inch).

| Species | Inoculant | Shelter | Planted | Alive | Dead | % Alive | Initial Hight (Inches) | Initial Diameter (mm) |

| Korean | Commercial | None | 25 | 15 | 10 | 60% | 16.2 | 6.5 |

| Korean | Commercial | Shelter | 25 | 22 | 3 | 88% | 16.1 | 6.0 |

| Korean | Local | None | 25 | 19 | 7 | 76% | 17.5 | 6.7 |

| Korean | None | None | 25 | 22 | 3 | 88% | 15.7 | 6.2 |

| Siberia | Commercial | None | 26 | 16 | 10 | 62% | 16.3 | 6.3 |

| Siberia | Commercial | Shelter | 25 | 17 | 8 | 68% | 13.7 | 5.5 |

| Siberia | Local | None | 25 | 20 | 5 | 80% | 14.8 | 5.9 |

| Siberia | None | None | 24 | 18 | 6 | 75% | 14.4 | 5.9 |

| Fraser | None | None | 286 | 283 | 3 | 99% | ||

| Balsam | None | None | 284 | 282 | 2 | 99% |

Fraser and Balsam fir survived at much higher rates than Korean or Siberian Pine trees regardless of how the Korean and Siberian pine trees were planted.

What caused individual pine trees to die is not clear since their initial size and root conditions were all very similar and death was randomly found throughout the orchard.

New growth on established 6-year-old Korean Pine on our farm in 2024 averaged 18 inches and was robust among trees, so the poor grown experienced on our newly planted Asian pine trees was likely attributed to their young age and the transplanting stress.

Statistical analysis after two growing seasons (April 2024-October 2025)

Survival:

The survival trends observed after one year continued to be present after two growing seasons. Presented in the table below is overall survival of Korean pine, Siberian pine, Fraser fir, and Balsam fir under different inoculant and shelter treatments from the planting in April 2024 to September 2025 (two growing seasons).

| Species | Inoculant | Shelter | Planted | Alive | Dead | % Alive |

| Korean | None | None | 25 | 22 | 3 | 88% |

| Korean | Local | None | 25 | 18 | 7 | 72% |

| Korean | Commercial | None | 25 | 13 | 12 | 52% |

| Korean | Commercial | Shelter | 25 | 21 | 4 | 84% |

| Siberia | None | None | 24 | 18 | 6 | 75% |

| Siberia | Local | None | 25 | 19 | 6 | 76% |

| Siberia | Commercial | None | 26 | 14 | 12 | 54% |

| Siberia | Commercial | Shelter | 25 | 15 | 10 | 60% |

| Fraser | None | None | 286 | 281 | 5 | 98% |

| Balsam | None | None | 284 | 279 | 5 | 98% |

Survival differed significantly among the four species under untreated conditions (no inoculant, no shelter). Fraser and balsam fir exhibited the highest survival rates, with 98% of trees alive after two growing seasons. Both Fraser and balsam fir survival rates were significantly greater than those of Korean and Siberian pine (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.005–<0.001). Survival of Korean pine (88%) and Siberian pine (75%) was lower but did not differ significantly from each other (p = 0.27). No significant difference in survival was observed between Fraser and balsam fir (p = 1.00). These results suggest species-specific differences in baseline survival, with Fraser and balsam fir showing markedly greater resilience in the absence of inoculant or shelter treatments.

Unexpectedly, inoculant treatment was associated with significantly lower survival in Korean Pine and Siberian Pine in the absence of shelters. For Korean fir, survival declined from 88% in the non-inoculated control to 72% with local inoculant and to 52% with commercial inoculant. Survival under commercial inoculation was significantly lower than the no inoculant control (p = 0.006) and lower than the local inoculant treatment (p = 0.04), whereas survival did not differ significantly between the local inoculant and control treatments (p = 0.17). For Siberian fir, survival was similar between the control (75%) and local inoculant (76%) treatments (p = 1.00), but was significantly reduced under commercial inoculation (54%) compared to the control (p = 0.04).

Shelter effects were evaluated under commercial inoculation only. Shelter significantly increased survival of Korean fir seedlings from 52% to 84% (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.008). In contrast, shelter had no detectable effect on survival of Siberian fir under commercial inoculation (54% without shelter vs. 60% with shelter; p = 0.78).

Overall, these results indicate treatment-by-species interactions. Commercial inoculation consistently reduced survival in both pine species, whereas shelters substantially mitigated this effect in Korean Pine, but not in Siberian Pine.

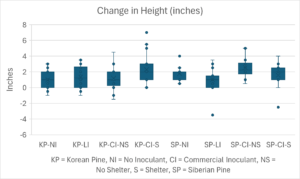

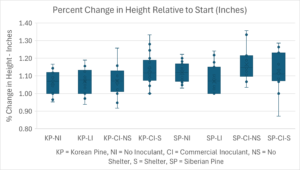

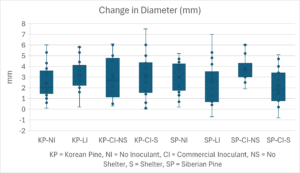

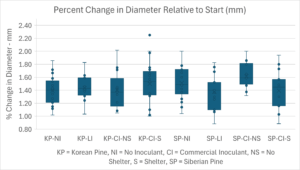

Statistical analysis of growth and condition after two growing seasons (April 2024-September 2025)

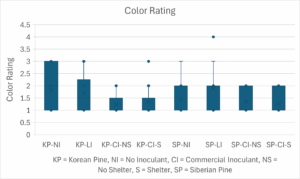

Below is a table summarizing average color, change in height and change in diameter of Korean Pine and Siberian Pine trees planted in April 2024 and measured again in September 2025 . Color rating is a scale of 1 to 4 where 1 is green and 4 is brown.KP = Korean Pine, SP = Siberian Pine, NI = No inoculant, LI = Local Inoculant, CI = Commercial inoculant, NS = no shelter, S = Shelter.

| Treatment | Number Surviving | Color Rating | Change in Height (Inches) | Change in Diameter (mm) | % Change in Height | % Change in Diameter |

| KP-NI | 22 | 1.82 | 0.98 | 2.46 | 106% | 139% |

| KP-LI | 18 | 1.72 | 1.33 | 3.09 | 107% | 143% |

| KP-CI-NS | 13 | 1.23 | 1.19 | 2.95 | 107% | 141% |

| KP-CI-S | 21 | 1.33 | 2.29 | 3.02 | 113% | 150% |

| SP-NI | 18 | 1.44 | 1.75 | 2.98 | 112% | 151% |

| SP-LI | 19 | 1.89 | 1.71 | 2.52 | 112% | 145% |

| SP-CI-NS | 14 | 1.36 | 2.54 | 3.81 | 116% | 162% |

| SP-CI-S | 15 | 1.27 | 1.57 | 2.13 | 113% | 139% |

Both Korean and Siberian pine had small increases in height after 2 growing seasons - the average increase in height was only 1-3 inches! Fraser and balsam fir grew about 12 inches in two years. When the percent change in height from April 2024 to September 2025 is calculated (Height Sept2025/Height April 2024), we found that Siberian Pine had significantly greater increases in height than Korean Pine (F₁,₁₃₅ = 4.71, P = 0.032), but height was not influenced by inoculant (F₂,₁₃₅ = 0.45, P = 0.64) or shelter treatments (F₁,₁₃₅ = 0.24, P = 0.63).

Both Korean and Siberian Pine also had marginal increases in stem diameter over two growing seasons - with averages increases in September 2025 being about 30-40% relative when planted in April 2024. Percent change in diameter did not differ among species, inoculant, or shelter treatments (P > 0.27 for all tests).

Most Siberian and Korean pine surviving to September 2025 were dark green (1 on our scale) or green (2 on our scale) indicating growth potential for future years. Color rating did not differ between the species (F₁,₁₃₅ = 0.19, P = 0.66) nor the shelter treatment (F₁,₁₃₅ < 0.001, P = 0.98), but trees with commercial inoculant were greener on average than those without inoculant (F₂,₁₃₅ = 4.17, P = 0.018).

Changes in soil chemistry from April 2024 to September 2025

A soil test conducted over the entirety of the field in September 2025 revealed relatively minor changes in macro and micro nutrients. Notably, while potassium was higher than in 2024, potassium was still below target and additional potassium is recommended for this field. Also notable was that cation exchange capacity increased from 2.8 meq/100 g in spring 2024 to 4.5 meq/100 g to September 2025. We suspect that grazing sheep on the field during two growing seasons may part of the reasons cation exchange capacity has started to increase.

Discussion:

The Korean and Siberian Pine trees consistently have the lowest first year survival rate of any tree we've planted at Ox Heights including European chestnuts, European walnuts, European hazelnuts, peaches, apples, pears, grapes, black walnut, white oak, swamp oak, cherry, Fraser fir, and balsam fir. Survival of the Korean and Siberian pines planted during 2024 was similar to first year survival of a small plot of Korean Pine planted at Ox Heights during 2017. The Korean pine planted in 2017 were not provided inoculant or shelter. Here, we found no improvement in survival was observed when Korean and Siberian pine planted in 2024 were provided inoculant or shelter.

Concerning to us was the new growth observed on the Korean Pine and Siberian pine upon their delivery to our farm. In our experience, trees should be dormant when transplanting. Whether the pine trees started growing in Ontario prior to shipment or whether they started growing while in transit to our farm. We suspect the latter is true since the nursery reported that the trees were dug and shipped as early in the spring as usual (they are located at similar latitude), and the trees were in the boxes for 7 days as they cleared customs review to be delivered to Michigan. If the warehouse the tree shipment was stored in was heated, it's conceivable the trees started pushing new growth during shipment. In hindsight, and with a tree order of this expense (~$8,000), we would have been better off spending a couple days picking up the trees in person rather than relying on shipment from Canada. Therefore, some of the differences in survival between the Pine trees and Fir trees could have related to how they were sourced. Fir trees were picked up directly from the nursery. The Pine trees were shipped and in transit for 7 days as they were processed by customs.

Also concerning was the small root systems of the Asian pines we received. We'd estimate that the Asian Pine roots were roughly 10% of the size of the fir tree roots. We do not know whether all Korean and Siberian trees have small root systems when young or if the small roots were a function of conditions in the nursery we procured the trees from.

Taken together, after two years we have 77 surviving Korean Pine and 66 surviving Siberian Pine and those still alive have dark green needles and look poised to grow well in subsequent years. However, with 60 trees lost in the project and an average cost per tree of $35, taking a $2,100 loss during crop establishment is a bit of gut punch for anyone. Therefore, as we consider if and how to replace the lost trees we are planning to test potted Korean and Siberian Pine trees because the transplant stress should be less and any microorganisms associated with the roots will be present in the potting soil. Of course, mailing potted trees is much more expensive or not feasible for most nurseries, so increasing the number of nurseries offering potted Korean and Siberian Pine trees would be helpful to farmers in the North Central Region. In our specific case, we purchased some Korean Pine nuts and are stratifying them now with the goal of having our own micro-nursery for planting these trees at our farm and selling to other farmers in Northern Michigan.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

About 12 on-farm demonstrations occurred during 2024 2025 with local farmers and the owner of Nutcracker Nursery (Quebec). Our website blog remained active and up to date and provided updates and educational information about the project. We also have You Tube videos of the project posted on our You-Tube channel.

Learning Outcomes

We reaffirmed that transplanting Korean and Siberian pine trees with very high survival rates is very difficult and that adding complementary mycorrhiza or shelters did not provide a clear solution for improving survival.

Part of the difficulty of transplanting Asian Pines is attributed to the scarcity of these trees in U.S nurseries and logistics involved with shipping these between countries. Therefore, additional domestic production of Korean and Siberian pine would likely increase the ease of establishing these orchards in the future.

Another aspect of the difficulty of transplanting Asian Pines is their relatively low vigor and small root systems when young. We wonder if most of the transplanting stress could be eliminated if the trees were received in pots rather than bareroot. Again, shipping potted trees 100s of miles and across international borders is not easy, so domestic nursery production of Korean and Siberian Pine would help provide sources of potted trees. Also, I suspect most farmers would be willing to travel a few hundred miles in the U.S. to pick up potted Korean and Siberian Pine trees especially if the cost per tree is similar to what we paid here (~$35).

In summary, given the beauty and nut production from Korean and Siberian pine trees and a lack of nursery production in U.S., we think nurseries in the North Central Region have opportunity to add these trees to their portfolio of tree offerings.

Project Outcomes

Marco Harvey owner of Nutcracker Nursery visited Ox Heights during October 2024. He was impressed with the overall farming system and was very interested in learning the fate of our Korean and Siberian Pine experiment. Marco also grows Korean and Siberia pine and has not been able to produce enough trees to meet the demand for his customers.

We think it would be valuable to further understanding bottlenecks for nursery production of Asian Pines in Midwest region of the U.S. and test whether transplanting potted Asian Pines results in higher establishment success than bare root Asian Pine trees (as done in this study).