Progress report for FNC24-1421

Project Information

My farm, located near Peoria, Illinois, is 176 acres total with 60 tillable acres. The farm has been in my family for over a century; I have owned and managed it since 2019. Forty-five acres are certified organic row crops (corn/soybean/wheat rotation with cover crops), eight acres are prairie strips under the Conservation Reserve Program, three acres are alfalfa, four acres are grass, and 110 acres are wooded. Cattle grazed the woodland until 2007 after which the woodland was passively managed. In 2020, a denitrifying woodchip bioreactor was installed to remove nitrates from tile water exiting the farm. In 2021, a dry dam was built to control erosion in a grass waterway. In 2022, the fields were certified organic.

The 110 wooded acres on my farm is degraded habitat dominated by invasive and undesirable woody species, including bush honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.) and Osage orange trees. Prior to European colonization, these wooded areas were dominated by prairie grasses with scattered white and northern red oaks, a community referred to as oak savanna. In protected slopes and ravines, the overstory may have shifted to a more closed canopy, oak-dominated natural community. Once common, these natural communities rarely persist on landscapes today, however within the 110 acres of woodland on my farm, many large white and red oaks remain.

Oak savanna is a fire-dependent landscape, requiring fire to remain healthy and diverse. A century of fire suppression has contributed to the proliferation of invasive woody shrubs, especially bush honeysuckle.

Prescribed burning is an important forest management tool, but a heavy infestation of invasive bush honeysuckle removes that tool from the toolbox. Bush honeysuckle kills herbaceous groundcover, which is required fuel for a prescribed fire.

Bush honeysuckle blocks sunlight to the forest floor by leafing out first in the spring and keeping its leaves longest in the fall. Additionally, it creates a dense understory that shades the forest floor during the growing season. Honeysuckle also takes moisture and nutrients away from native plants. A severe honeysuckle infestation results in little, if any, herbaceous groundcover underneath. This lack of groundcover promotes soil erosion. Furthermore, a prescribed burn, necessary to improve forest health, is simply not possible because there is no fuel for a fire.

The standard practice for bush honeysuckle control today is treatment with the herbicide glyphosate. However, blanketing our woodlands in glyphosate is detrimental to the health of humans, desirable plants, insects, and animals (van Bruggen, et al., 2021; Smith, et al., 2021).

The problem to be solved is how to control bush honeysuckle in an environmentally sound, sustainable way, that is, without the use of herbicides. To be successful, the control method must reduce honeysuckle sufficiently to allow establishment of enough herbaceous groundcover for a good quality prescribed burn in the future.

Results to be added in the final report.

van Bruggen, A.H.C, M.R. Finckh, M. He, C.J. Ritsema, P. Harkes, D. Knuth, and V. Geissen. 2021. Indirect effects of the herbicide glyphosate on plant, animal and human health through its effects on microbial communities. Frontiers in Environmental Science 9.

Smith, D.F.Q, E. Camacho, R. Thakur, A.J. Barron, U. Dong, G. Dimopoulos, N. Broderick, and A. Ccasadevall. 2021. Glyphosate inhibits melanization and increases susceptibility to infection in insects. PLoS Biology 19(5): e3001182.

Objectives:

- Compare non-herbicide methods for control of invasive bush honeysuckle on 20.6 wooded acres divided into five test units. Methods include targeted goat grazing, manual mechanical cutting, machine pulling, and machine shredding.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of lightly seeding native grasses to determine if seeding enhances herbaceous groundcover

- Assess which methods promote sufficient herbaceous groundcover to enable a future prescribed burn

- Determine which method sequence, if any, should be expanded to larger acreage on my farm

- Share findings with the community to encourage environmentally sound approaches for brush control

Proposed Solution:

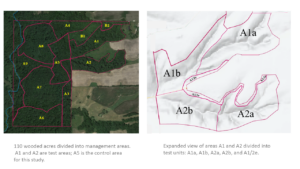

Two areas, A1 and A2, were identified within 110 acres of degraded oak-dominant natural communities and divided into five test units as shown in Figure 1. Adjacent area A5 was used as an untreated control for the study. Areas A1 and A2 both have steep ravines (up to 60% slope) with incised creeks running through the bottoms. At the start of the study, all areas had a thick understory of bush honeysuckle, a severe infestation. For historical reference, Figure 2 shows aerial views of the farm in 1939 and 2019. In 1939, the woodland is a more open landscape in contrast to the completely closed canopy in 2019.

The table below summarizes the original study design. Modifications made in the field are discussed in the “Materials and Methods” section.

|

Method number |

Test plot |

Acreage |

Pretreatment (winter 2023) |

Treatment 1 (spring 2024) |

Treatment 2 (fall 2024) |

Treatment 3 (spring 2025) |

|

1 |

A1a |

5 |

None |

Goats&Cut |

Goats |

TBD |

|

2 |

A2a |

4.8 |

None |

Goats |

Cut |

TBD |

|

3 |

A1b |

5 |

None |

Goats |

Goats |

Goats&Cut |

|

4 |

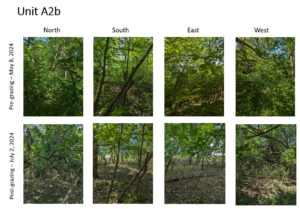

A2b |

4.8 |

None |

Goats |

Goats&Cut |

TBD |

|

5 |

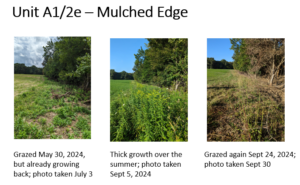

A1/2e |

1 |

Mulch |

Goats |

Goats |

TBD |

In the table, “Mulch” means shredding with a mulching head on a skid steer. “Goats&Cut” means after goats have grazed for a couple days, then manually cut honeysuckle taller than goat-graze height to near ground level. “Cut” means manually cut all honeysuckle with chain saws and hand tools to near ground level. “TBD” means to be determined based on treatment effectiveness in 2024.

Goats can graze to a height of about 6 ft, whereas honeysuckle grows up to 15 ft. Therefore, mechanical removal was included in each method to drop tall honeysuckle to near ground level.

To test the value of seeding, native grass seed (~1 lb/acre) was hand broadcast in half of each unit.

This study is intended to answer the question of which method sequence, with or without seeding, provides the best preparation for a future prescribed burn.

Research

Goat Grazing

Targeted goat grazing was managed by Barnyard Weed Warriors Iowa (BWWI) (Swan, IA), a firm that owns the goats and takes responsibility for all aspects of goat grazing. Goats were allowed to graze in mobile paddocks with portable electric fencing and a solar-charged power source. When goats had sufficiently grazed an area, they were moved to a new portable paddock.

Metrics

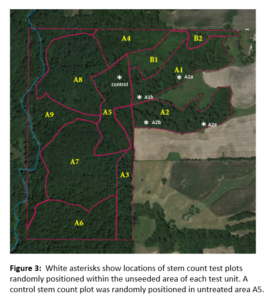

Honeysuckle stem counts were taken in 21 ft by 21 ft square test plots located within the unseeded area of each unit (excluding unit A1/2e) as well as within the untreated control area A5. Test plot locations were randomly selected by mapping a grid onto the unseeded area of each unit, numbering each square in the grid, and using a random number generator to choose squares within the grid for test plot locations. Figure 3 identifies the location of each plot. We drove steel T-posts into the ground at the four corners of each test plot to mark the locations in the woods.

We conducted stem counts in each test plot and the control plot before and after each goat grazing period. Stem counts included the following:

- Within each plot, all honeysuckle with stem diameter of at least 0.3 in at 18 in height were counted. Multiple stems from one root were counted as one honeysuckle.

- Within each plot, percent honeysuckle cover was visually estimated.

- Within each plot, average honeysuckle height was visually estimated.

- Photos were taken in all four directions from the northwest corner of each test plot.

Two to three people participated in the stem counts so that we could average our individual visual estimates for honeysuckle average height and percent cover. Stem counters included the landowner, private lands biologist from US Fish and Wildlife Service Partners Program, and biologist from Illinois Recreational Access Program.

Pre-treatment (Winter 2023)

Invasive Plant Removal and Maintenance (IPRM) (Gilson, IL) used a skid steer with mulching head to mulch brush around the flat edges of areas A1 and A2. This mulched area is labeled A1/2e on the map in Figure 1.

Treatment 1 (Spring/Summer 2024)

Goat Grazing

BWWI delivered 100 adult doe goats in mid-May 2024. We anticipated that grazing areas A1 and A2 (20.6 acres) would take 20 to 30 days, but it actually took 42 days due to the density of honeysuckle and steep terrain, which made fencing problematic. A path had to be hand cleared in order to set the fence, but the honeysuckle was so thick that it was difficult to find routes to cross the steep ravines. For example, the worker could be cutting a path with a chain saw and then suddenly come upon a very steep drop and have to change course.

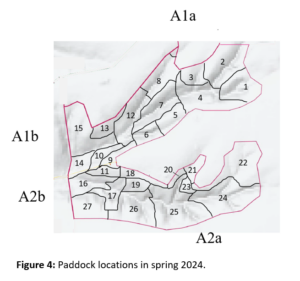

Figure 4 shows paddock locations in spring 2024. Paddock size varied from 0.2 acres to 1.6 acres, with goats usually having access to more than one paddock. Stocking rate ranged from 40 to 100 goats/acre. The goats grazed about 0.4 ac/day in paddocks 1 through 24, resulting in nearly complete defoliation of all they could reach. The goats were allowed less time in paddocks 25 through 27 due to BWWI commitments; the goats had to be returned to Iowa for another job. Goats grazed about 1 ac/day in paddocks 25 through 27.

Mechanical Clearing

The experiment plan called for clearing unit A1a in spring 2024. BWWI started mechanically clearing A1a in May 2024 as scheduled, but wasn’t able to complete clearing until September 2024 due to unanticipated labor shortages. In machine-accessible areas, BWWI used a skid steer with puller attachment. The puller is able to grasp honeysuckle stems greater than about 1 inch in diameter and pull them out by the roots. IPRM manually cleared the steep ravines (about 2.5 acres) in unit A1a with chain saws and pull saws in August 2024, using a crew of 10 people. Dropped honeysuckle in unit A1a was piled and burned by BWWI or mulched by IPRM.

Treatment 2 (Fall 2024)

Goat grazing

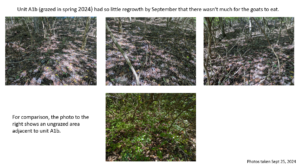

BWWI delivered 100 adult doe goats in late August 2024. Grazing commenced in area A3, an area not included in this SARE study but noted here due to some paddocks spanning unit A2b and area A3. The southern part of unit A2b had sufficient vegetation for the goats, as it was grazed less heavily in the spring than the other test units. When the goats reached areas that had been heavily grazed in the spring, however, there just wasn’t enough for them to eat, so BWWI took 50 goats back to Iowa on September 15, 2024. Therefore, paddocks 10 through 13 were grazed with only 50 goats. Areas A1 and A2 had not grown back over the summer as much as we had anticipated. In fact, we decided not to graze parts of units A1a and A1b at all, because there was so little foliage within goat graze height.

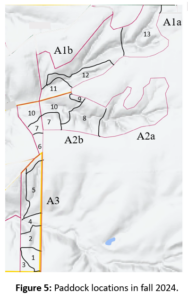

Figure 5 shows paddock locations in fall 2024. Paddock size varied from 1 to 3 acres in units A2b, A1b, and A1a. Unit A2a was not grazed in fall 2024, as per plan. Stocking rate ranged from 20 to 60 goats/acre. Fall grazing in units A2b, A1b, and A1a lasted 14 days.

As planned, grazing ran in the opposite direction in fall 2024 (area A2 followed by area A1) compared to spring 2024 (area A1 followed by area A2).

Mechanical Clearing

BWWI started clearing units A2a and A2b in September 2024 using a skid steer with puller. BWWI continued hand clearing units A2a and A2b with one to four people during November and December, completing about eight acres. IPRM finished hand clearing the final two acres in units A2a and A2b in January 2025 using a crew of eight people.

IPRM cleared unit A1b in mid-November 2024 using a skid steer with puller and mulching head, and a crew of eight people with chain saws and pull saws. Along with honeysuckle, IPRM mulched cull trees up to 6 inches in diameter in unit A1b.

As of this writing, all of areas A1 and A2 has been grazed once (or twice) and mechanically cleared.

Seeding

To test whether seeding helps establish native groundcover, the following were broadcast in the east half of each unit. Seeds were purchased from Kelly Seed and Hardware (Peoria, IL).

|

Native seed |

Seeding rate |

|

Canada wild rye |

0.5 lb/ac |

|

Virginia wild rye |

0.5 lb/ac |

|

Little bluestem |

0.1 lb/ac |

A mixture of the above seeds was hand broadcast as follows:

Unit A1a east half: ~½ lb/ac in May 2024 while goats grazed there, ~½ lb/ac in February 2025 after mechanical clearing

Unit A1b east half: ~1 lb/ac in May 2024 while goats grazed there

Unit A2a east half: ~1 lb/ac in January 2025 after mechanical clearing

Unit A2b east half: ~1 lb/ac in January 2025 after mechanical clearing

Visual Timeline

Figure 6 shows timing for stem counts, goat grazing, mechanical clearing, and seeding.

To expand on the legend definitions:

- Intensive goat grazing: nearly complete defoliation of everything the goats could reach

- Moderate goat grazing: at least 50% defoliation of everything the goats could reach

- Some acres not grazed at all: there wasn’t enough foliage for the goats to eat in the full unit (areas outside numbered paddocks in Figure 5 were not grazed)

- Intermittent mechanical clearing: while goats were grazing, BWWI mechanically cleared as time allowed, though much of the time they were tending to the goats and building new paddocks

- Intensive mechanical clearing: crews of workers focused entirely on mechanical clearing

Modifications to the Original Experiment Plan

Experiment plans on paper sometimes require adjustment in the field. The table below describes the modifications made to the original plan.

|

Original Plan |

Modification |

Reason |

|

Mechanically drop honeysuckle taller than goat graze height in the paddock where goats were grazing to allow goats to eat the leaves |

Cut honeysuckle after the goats had been moved to another paddock, so goats were not present during cutting |

The original plan posed a risk to the goats. The honeysuckle was so thick that it had to be piled after cutting to make space to maneuver. We saw a goat that had climbed deep into a pile – only her tail and hind legs were visible. Goats’ rear-sloping horns enable them to push forward through obstacles, but then their horns can get entangled when they try to back out. We were concerned that goats could get caught or get poked in their eyes from diving into honeysuckle piles. |

|

Cut honeysuckle taller than goat graze height by hand with chain saws and hand tools |

Used a skid steer with a puller attachment to pull larger honeysuckle in machine-accessible areas; steep ravines were cleared by hand |

The original plan was too slow and labor intensive. Furthermore, after the goats had opened up the understory, we could see that more areas were machine accessible than we had originally thought. Use of a skid steer is a trade-off – track wheels and pulling tear up the soil exposing it to erosion risk, but pulling honeysuckle means it won’t resprout. It was a compromise I was willing to make due to the high density of honeysuckle. |

|

Hand broadcast native grass seed in spring 2024 during goat grazing so that goat hooves could push seeds into the soil |

Seeded part in May 2024 and part in January and February 2025 |

Grazing in spring 2024 took much longer than expected and lasted into the summer. While we were able to seed some areas in spring while goats grazed there, we decided to wait until winter 2025 to seed other areas, because (1) seeding in summer is generally not as effective as seeding in spring or fall/winter, and (2) subsequent mechanical clearing would disturb young sprouts. Frost seeding following mechanical clearing seemed like a better approach. |

|

Mechanically clear unit A1a in spring 2024 |

Clearing unit A1a started in spring 2024, followed by a summer break, then clearing was completed in September 2024 |

Unanticipated labor shortages |

|

Mechanically clear units A2a and A2b in fall 2024 |

Clearing units A2a and A2b started in fall 2024, but wasn’t completed until January 2025 |

Unanticipated labor shortages |

|

Goat grazing in units A2b, A1b, and A1a in fall 2024 |

Goats grazed unit A2b, but only half of each of units A1b and A1a in fall 2024 |

Regrowth by mid-September 2024 was insufficient to warrant fencing all of units A1b and A1a; there just wasn’t enough for the goats to eat and keep them healthy. Figure 7 shows representative photos. |

|

Mechanically clear unit A1b in spring 2025 |

Mechanically cleared unit A1b in fall 2024 |

The goats thoroughly defoliated honeysuckle they could reach, that is, up to about 6 ft, but the tall honeysuckle still looked healthy and went to seed in the fall. Therefore, we decided to clear unit A1b in fall 2024 instead of spring 2025. This change in timing meant units A1b and A2b would have the same sequence of methods. To differentiate units A1b and A2b, we decided to mulch the honeysuckle and mulch cull trees up to 6 inches in diameter in unit A1b. In contrast, unit A2b downed honeysuckle was piled and burned and cull trees were left standing. |

|

Measure percent honeysuckle cover over each unit using a drone |

Estimate percent honeysuckle cover visually in each test plot only (not the full unit) |

I discovered that my farm is in a “no fly” zone due to proximity of the General Wayne A. Downing Peoria International Airport, which is about three miles away. |

The study design adjusted with field modifications is shown below.

|

Unit |

Acreage |

Pretreatment (winter 2023) |

Treatment 1 (spring/summer 2024) |

Treatment 2 (fall 2024) |

Treatment 3 (2025) |

|

A1a |

5 |

None |

Goats&Pull&Cut |

Goats |

Goats |

|

A2a |

4.8 |

None |

Goats |

Pull&Cut |

Goats |

|

A1b |

5 |

None |

Goats |

Goats&Pull&Cut&Mulch |

Goats |

|

A2b |

4.8 |

None |

Goats |

Goats&Pull&Cut |

Goats |

|

A1/2e |

1 |

Mulch |

Goats |

Goats |

Goats |

The original experiment plan had ‘TBD’ for treatment 3. We have decided on goat grazing over mechanical clearing for treatment 3 because goats are better than humans at climbing over the steep terrain and goats don’t disturb soil the way machinery does.

A distinction should be made between test plots (where stem counts occurred) and units (in which test plots were located). Test plot A1a was outside the grazed area in September 2024 (due to lack of foliage, only half of unit A1a was grazed then). Otherwise, all test plots received the same spring and fall grazing as their respective unit. With regard to mechanical clearing, only test plot A1a had been cleared by the September 30, 2024 stem count date.

The goats did an outstanding job in spring 2024 of opening up the woods by defoliating everything to about 6 ft in height. This made subsequent mechanical clearing much easier, because machine operators could see where they were going and manual clearing was less encumbered by brushy undergrowth.

Goats not only ate the honeysuckle leaves, they also ate some of the smaller branches, and they climbed on the trunks and cracked some of them off. Video 1 shows goats working together to stand on honeysuckle and bend it over to eat the leaves.

Video 2 shows a BWWI manager calling goats to a new paddock that we had just completed fencing. Upon reaching the new paddock, the goats immediately started eating honeysuckle; they go right to work once allowed into a new paddock.

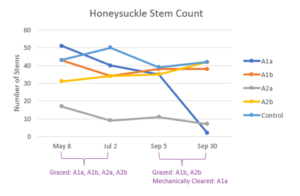

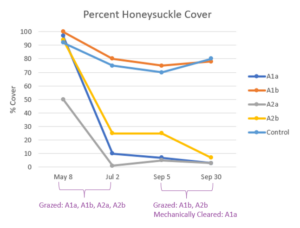

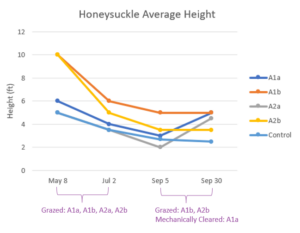

Graphs of the main metrics for honeysuckle (number of stems, percent cover, and average height) in the test plots and control plot are shown in Figures 8 through 10. The data are rather noisy, as it is difficult to accurately estimate the metrics. Furthermore, these metrics are not independent variables and do not consistently correlate. Nonetheless, the metrics provide insight into the effectiveness of the treatments in each unit.

As shown in Figure 8, the number of honeysuckle stems did not change much across the four count dates, except in the case of test plot A1a. The last count in the series on September 30, 2024 shows a large drop in the number of stems in test plot A1a due to mechanical clearing. The other three test plots had not yet been mechanically cleared by September 30, 2024.

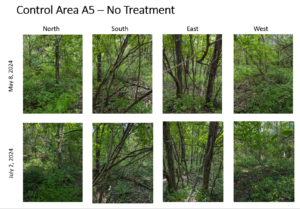

Goat grazing generally had a large impact on honeysuckle percent cover, as shown in Figure 9. Grazing occurred in May and June 2024, and the drop in percent cover from May 8 to July 2, 2024 count dates is significant. The goats thoroughly defoliated the honeysuckle they could reach. Only test plot A1b did not show a significant drop in percent cover, due to large honeysuckle above goat graze height in that area. An additional drop in percent cover is exhibited for test plot A2b in September 2024. Test plot A2b was moderately grazed in the spring and heavily grazed in the fall, leading to an additional decrease in honeysuckle percent cover by September 30, 2024. The untreated control plot A5 shows little change in honeysuckle cover over the entire period.

Figure 10 reveals that spring grazing slightly reduced honeysuckle average height compared with the untreated control. Honeysuckle average height decreased 40% on average in the test plots from May 8 to July 2, 2024 while average height decreased 30% in the untreated control plot A5 during that same time period. Average height in the untreated control plot A5 continued to decrease slightly throughout the year, suggesting a time-of-year effect. Honeysuckle average height rebounded by September 30, 2024 in test plots A1a and A2a. Test plot A1a was mechanically cleared in September 2024 but a couple rather tall honeysuckle remained after clearing, resulting in an increase in average height though far fewer stems (see Figure 8). Unit A2a was not grazed by design in the fall, but neither was the untreated control for which height did not rebound. This suggests that the rebound in honeysuckle average height for test plot A2a may be within the noise in the data.

Figures 8 through 10 show little difference from July 2 to September 5, 2024 for any of the three metrics. There was not much honeysuckle growth over the summer. Weather over the summer was not atypical for the area (CIProud.com, ‘Looking back at meteorological summer 2024’), so lack of growth cannot be blamed on unusual weather. Photos in Figure 11 of the mulched unit A1/2e show thick growth of mostly weeds over the summer, as unit A1/2e was in the sun. In contrast, the other units had very little regrowth over the summer presumably due to heavy shade. Although percent honeysuckle cover was generally low in the woods after spring grazing, the ground was still heavily shaded from midstory and canopy trees.

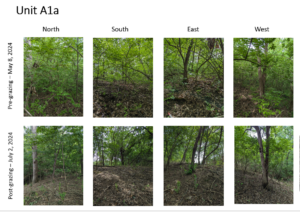

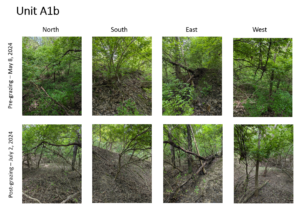

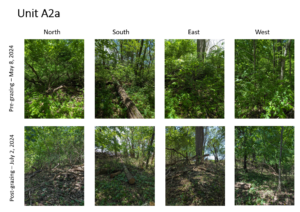

It was very difficult to walk through the woods before goat grazing due to heavy underbrush, but after spring 2024 grazing, walking (and seeing) through the woods was remarkably easier. Photos taken during the stem counts show the difference pre- and post-grazing (Figures 12 through 15). In contrast, honeysuckle in the untreated control area A5 remained thick (Figure 16).

It was hoped that goats could eat honeysuckle berries during fall grazing, because after passing through the goats’ digestive tracts, honeysuckle seeds may no longer be viable. However, we found that the berries were generally higher than the goats could reach. The shorter honeysuckle plants did not produce berries and were even struggling to produce leaves after having been defoliated by the goats in the spring.

Stocking rate varied from about 20 to 100 goats/ac, but this did not appear to impact effectiveness. This result agrees with a study from Purdue University (Rathfon, et al., 2021), in which stocking rate was a controlled variable. Investigators reported that lower stocking rates extended grazing duration, but did not affect grazing effectiveness.

The main objective of this study is to determine which method sequence will provide the best preparation for a prescribed burn, and that is not yet known. This result should be available in late 2025 after completion of treatment 3.

Kitchens, Nathan. September 4, 2024. Looking back at meteorological summer 2024. CIProud.com. https://www.centralillinoisproud.com/weather-headlines/looking-back-at-meteorological-summer-2024/

Rathfon, R.A., S.M. Greenler, and M.A. Jenkins. 2021. Effects of prescribed grazing by goats on non-native invasive shrubs and native plant species in a mixed-hardwood forest. Restoration Ecology 29(4): e13361.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Goat grazing for brush control is pretty much unknown in my area and neighbors were very curious when they heard that I had hired a goat grazing company. Four nearby farmers and four local landowners came to see the goats in action. Three staff members from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) visited and brought two summer interns along. A forester whom I met at a local festival came to see the goats, as he is considering using goat grazing in an urban setting.

The implementation of the biological control practice (goat grazing) has been a beneficial learning opportunity for several area conservation practitioners who assist Illinois private landowners in habitat management initiatives. NRCS staff, local Pheasants Forever farm bill biologist, US Fish and Wildlife Service private lands biologist, Illinois Recreational Access Program biologist, and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources regional forester have been monitoring the project, documenting lessons learned, and coordinating best management practices for future projects utilizing biological control for brush management.

I presented my SARE goat study at a biweekly meeting titled “Meaningful Conversations,” attended by a group of retired women scientists in which we discuss innovative research on protecting the environment and mitigating climate change.

Planned outreach activities in 2025 include:

- Field day at my farm

- Articles in outlets such as Illinois Outdoor Journal, Peoria County Farmer, Pheasants Forever Facebook page, and Farmweek.

Learning Outcomes

It was difficult to find a goat grazing company with enough goats to handle 20 acres, as many companies have too few goats and prefer smaller jobs. I finally found an out-of-state company who was willing to travel to my farm. As goat grazing becomes more popular, I hope there will be more options locally.

Despite the voracious appetite of the goats and their effectiveness at defoliation, they were unable to reach mature honeysuckle, which can grow to heights of 15 ft or more. Therefore, mechanical clearing is absolutely necessary in conjunction with goats to eradicate mature stands of honeysuckle.

My preliminary recommendation for controlling a severe infestation of bush honeysuckle on steep terrain is a method sequence of goat grazing in spring (to open up the understory), then mechanical clearing in fall (to drop the tall honeysuckle that goats can’t reach), then goat grazing the following year (to knock back resprouts and new shoots).

Project Outcomes

This work is a wonderful collaboration with NRCS, US Fish & Wildlife Service Partners Program, Illinois Recreational Access Program, and Pheasants Forever. These organizations have provided technical assistance, in-kind labor, and/or financial support. I am fortunate to work with such skilled, knowledgeable people.