Progress report for FNC24-1429

Project Information

The farm is a small family farm in central Iowa used to grow corn, soybeans, and alfalfa. The soil of the area involved in SARE research is loamy with moderate drainage, neutral slope, high fertility, and has been used in standard chemical intensive corn and soybean rotation for decades.

In April 2024 chestnuts and other perennials were planted in 8 acres of a former corn and soybean field which had been planted with cereal rye as a cover crop. The chestnuts were provided by Canopy Farm Management as bare root saplings, and were moderately successful. They were planted by hand, protected against pests and weather with a 5' tree tube and stake from Plantra, and irrigated by drip irrigation when necessary.

Over the 2024 growing season pests posed significant challenges, such as deer eating the tops of highly successful trees that grew beyond the protection of their tree tubes, mice making homes in the tree tubes and nibbling on the base of the tree, raccoons chewing through the side of a tree tube to eat wasp nests, and ground hogs or gophers chewing through the side of a tree tube to eat the entire tree. To discourage these activities, the bases of the tree tubes were wrapped in chicken wire, and the tree tubes were lifted up a half foot or so to fully protect the tree top where necessary.

The weather was extremely difficult. After a three year drought, record breaking rains fell in May and June, with May being the 8th wettest May since record keeping began in 1872. This was followed by no rain from mid August to mid October, with September being the driest September in 152 years on record. To reduce soil moisture loss, reduce soil temperature fluctuations, and provide many other benefits, mulch was added around every tree. The drip irrigation system went from completely unnecessary in June to absolutely vital in September for the newly established trees.

Before receiving this grant, several non commercial sustainable practices were done by Tom Peterson. Native trees such as oaks, cottonwoods, and willows, and fruit trees such as cherries, peaches, and apples were planted and nurtured in many non field areas of the farm. Invasive plants such as thistle, parsnip, and honeysuckle were regularly and thoroughly removed. Working with DNR forester Joe Herring, a forest stewardship plan was developed for the adjacent woodlot, and several invasive plants and honey locust trees were removed to make way for native trees.

Steady slow irrigation is generally the most optimal for plant growth, plant health, soil health, erosion control, and other agricultural aspects. Unfortunately the weather rarely rains in a steady slow stream; instead, plants are frequently stressed or killed by too much or

too little water. Too much water can be somewhat controlled by cover crops and buffer strips, but these techniques are not

widespread and can take time and money to develop. Too little water can be somewhat remediated by irrigation, but current

irrigation methods can be expensive, complicated, and require large amounts of water.

Our specific application requires providing regular moderate amounts of water to newly planted young chestnut trees. Current irrigation techniques are designed for high density gardens or annual crop fields, but commercial tree planting is done at large scale and low density (tens of trees per acre). These tree plantings are better modeled as discrete points that require water, rather than an entire field that requires uniform irrigation. Thus most trees are watered by hand using water from hoses and buckets with small holes to slowly drip water into the ground, or with custom irrigation setups grafted onto existing irrigation systems.

Our solution is clay pots with

rain and dew catching systems. Pots have been used for thousands

of years as irrigation containers whose walls slowly transfer

water from the pot to the surrounding soil, autoregulate by

increasing irrigation in dry soil and decreasing irrigation in

wet soil, provide water more directly to roots, and can be easily

filled by hand. Their research has been restricted to biomes of

sandy soils in arid or semi arid climates, all unlike Iowa (see

for example “The auto-regulative capability of pitcher irrigation

system”, Abu-Zreig et al, 2006). Each pot will have a water

collector to catch and store rain and passively collect dew every

night. Dew varies greatly but may average 0.2 liters per square

meter per night (“A review: dew water collection from radiative

passive collectors to recent developments of active collectors”,

Khalil et al, 2015). This will reduce the amount of water and

labor required for irrigation and provide myriad other benefits,

all for no energy and no additional carbon footprint during

operation.

The trials of this research

project will use different configurations of pots and water

collectors to maximize data gained and quantify the influences of

the many variables. Pots will be manufactured in the shape of

cylinders with radius 1 foot, height 1 foot, and a small center

hole on top. They will be buried a couple inches deep near a

tree. Water collectors will be plastic sheeting in 3 foot by 3

foot squares that are secured and supported by four 2 foot high

poles, with one pole at each vertex of the square, to form an

inverted pyramid which rain and dew will trickle down the sides

of to be collected in the pot. A hole will be made in the

sheeting to fit the tree into.

10 pots and water collectors will

provide an experimental baseline. The other trials will provide

comparisons with modified configurations of 5 with an additional

dew condenser attachment, 5 with a larger water collector of 4

feet by 4 feet, 3 with no water collector, 2 sealed to not

collect water at all, and 5 buried on top of a small barrier

designed to restrict water flow more primarily to the

tree.

3 plastic pots impermeable to

water and with water collectors will be used as controls for rain

and dew to measure these as the water will be partially absorbed

and distributed in the trials. These plastic pots will be

paired and the amount of rain or dew caught will be

measured by weighing with scales.

For controls we will measure the

soil moisture of nearby areas of grass, mulch, and trees without

pots.

If rainfall is sufficient, no

external irrigation will be provided. If rainfall is

insufficient, external irrigation will be provided with equal

amounts of water in all cases in order to sustain the

trees.

Rainfall, humidity, and

temperature are key variables that will be measured locally using

appropriate instruments.

Our objective is to demonstrate

the viability of pots with water collectors by measuring

irrigation rate, dew collection rate, and soil moisture

dispersion rate in a wide variety of trials, control

configurations, and weather. The data will be collected during

the growing season of second half of April to October, and

analyzed and disseminated during the dormant season of November

to first half of April. Outreach discussing initial data will be

done after the first growing season and more comprehensively done

after the second growing season.

2024 update: 2024 was mostly focused on research, development, design, site preparation, and initial field testing. 2025 will focus on full testing to achieve the project goals. More irrigators will be purchased and made. UV stabilized plastic or fabric sheeting will be acquired and deployed as rain and dew catching systems. Data will be collected over a longer period of time and will include rain events.

Research

Clay pots of the intended dimensions were not commercially available, and couldn't be easily or cheaply custom made. Smaller clay pots with drainage holes were available but more expensive than anticipated. As a compromise, some smaller clay pots were purchased and their holes were sealed with a small piece of HDPE and silicone caulk, and large barrel containers were made by cutting a used standard 55 gallon HDPE plastic barrel in half, cutting a hole in the base of each half, and sealing the hole with a clay saucer secured with silicone caulk. The barrel half was oriented with the clay saucer in the soil and the open end pointed up. The clay pots and the barrel's clay saucer were both placed only about an inch within the soil. The thick plastic sheeting intended to catch rain and dew in the field was not used because of the lack of rain, but a section used for set up and testing became brittle and began to break into pieces. This is probably caused by UV light; in the future some other UV stabilized plastic or fabric sheeting will be necessary.

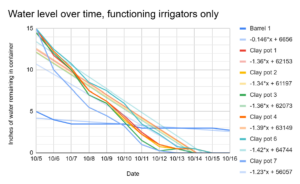

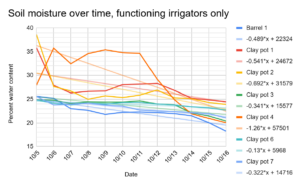

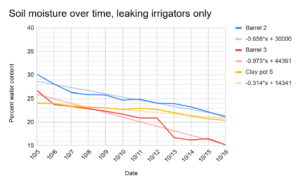

Despite the material challenges, a field trial was conducted to test the functionality of the irrigators and determine the rate of water distribution into the soil. Ten irrigators were deployed and each initially filled with about three gallons of water. No additional water was added, and no rain fell during this time. The irrigators were topped with heavy pieces of wood to prevent wildlife interference. Soil moisture data was taken at about 9 AM for ten days using a Lutron Soil Moisture Meter PMS-714 designed to measure at a depth of about 7.5 inches. Each irrigator had two data collection sites, each about one foot away from the irrigator and the tree, and the measurements from these two sites was averaged to obtain the final soil moisture value. The water level of the irrigators was also recorded. Three of the ten irrigators leaked all their water after the first day, but thereafter served as unirrigated control sites.

Of the seven non leaking irrigators, four produced data that fit decently well with a linear trendline (average slope -0.32 with std dev 0.15, average R squared of 0.77). Three had large outliers that did not fit well with a linear trendline (average slope -0.83 with std dev 0.33, average R squared of 0.47). The leaking irrigators fit very well with a linear trendline (average slope -0.65 with std dev 0.38, average R squared of 0.92). Finally the water levels of the non leaking clay pots fit very well with a linear trendline (average slope -1.35 with std dev 0.06, average R squared of 0.9).

The data was collected over a short time during which no rain fell, and cannot provide strong conclusions. However the reduced soil moisture loss -0.32 for the non leaking irrigators vs -0.83 for the leaking irrigators support the hypothesis.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

2024: consultations between farmer Reuben Peterson and consultant Dr. Kapil Arora.

Learning Outcomes

The paucity of data in 2024 does not allow strong conclusions to be drawn. The field had easy access to water and electricity, and vital drip irrigation was straightforward to set up. If this was not the case, such as in a more remote planting, this slow watering technique could save water, time, and money by only requiring supplemental watering once every two weeks during dry periods.