Progress report for FNC25-1452

Project Information

I started producing hickory oil in 2022. Since then, I have scaled up my operation to become the largest in the country. I will produce about 70 gallons of hickory oil this year, probably more than all the other producers combined. I am one of very few producers who are pioneering this new industry. I have already made innovations in the harvest and processing practices which the other major producers have adopted or will soon adopt. Currently there is little or no university research on yellowbud hickory oil, so we as producers are working together to put it on the map. So far, I have operated without grant funding or other public support.

My background growing up on a farm has provided me with the wide array of skills necessary to create and operate a new farm enterprise. This includes problem solving, a strong work ethic, responsibility, machinery operation, mechanical proficiency, construction, neighborliness, financial prudency, market awareness, and more.

My B.S. in environmental science has deepened my knowledge of natural systems and my passion for finding ways that humans can live in harmony with them. Specifically, I have knowledge of basic ecology, hydrology, and soil science. I am proficient with GIS and data analysis. I can identify most woody perennial species in my area, and have observed them intentionally for multiple years. I'm deeply concerned about climate change and its impact on food production. I'm committed to finding ways to reduce food production emissions, mitigate the risk climate change poses to food production, and produce food without destroying ecosystem functions.

My work experience in wildland firefighting has deepened my understanding of forest ecosystems and honed my skill as a sawyer. I'm conscious of the historical role of fire in Western and Midwestern forest and savannah ecosystems, and the impacts the removal of fire has had. My chainsaw and tree falling expertise will be important in the forest management aspect of this project.

Finally, I have participated in two perennial agriculture internships- one with The Land Institute, and one with The Savanna Institute. These opportunities have deepened my understanding of perennial ag systems, and the latter included a focus on tree crops (chestnuts). The professional connections I've made in these places have and will continue to be vital to my own research.

The broad problem we are all facing is how to live on this planet without destroying it and ourselves along with it. This can be more narrowly applied to my specific situation: how can I manage wooded ecosystems in Southeast Iowa to produce food without compromising their ecological integrity? This question led me to my interest in hickory oil. By harvesting the nuts from this common tree, it is possible to produce a substantial amount of high quality culinary oil. However, some management may be important to increasing both oil yield and ecosystem health. This brings us to the final and most specific question: what are the best woodland management practices that promote both production and ecosystem health while remaining feasible and replicable?

Objectives: This demonstration and education project will focus on managing local woodlands using best known practices, and sharing reflections on the process with a unique emphasis on hickory oil production. While timber stand improvement is a common practice, it has not in modern times been done with a specific focus on promoting Carya cordiformis nut production. Managing land typically is done with either an agricultural lens or a conservation lens; this project is designed to show that both can happen simultaneously with mutual benefit. In addition to a written report for this grant, I will focus on disseminating information through exiting networks, specifically through presentations at the Savannah Institute's perennial farm gathering in October 2026, the Northern Nut Growers Association annual meeting in July 2026, and for the Johnson County Food Policy council (a neighboring county to mine). I will also include information on my website.

Solution: The first management strategy I will pursue is thinning. Historically, the presence of fire would have kept stem counts lower, especially in oak or oak-hickory savannas, which once covered 15% of Iowa. I will manually eliminate trees to achieve about 30-70% canopy cover over time, depending on the site. I will focus on preserving oaks, hickories, and some black walnuts, while reducing the amount of hackberries, mulberries, and non-native species. I will do this with advice from my state forester, Bailey Yotter. We have already had the opportunity to meet and walk through one woodlot to discuss appropriate management. Thinning is also important for nut production. In chestnut farming, it is important to maintain the trees with as broad a canopy as possible. My observations with hickories are similar. Open-grown trees consistently yield higher than trees in dense forests. In time, thinning forests should increase nut production.

The next management focus will be on invasive brush. The majority of my sites are overgrown with multiflora rose and honeysuckle, and the increased light that comes with thinning will only encourage their growth. There are four main tools I have used to address this issue: digging, mowing, livestock, and burning. Each strategy has advantages and drawbacks, which I will explore and reflect on in my results. This brush management is also important for nut harvest, which requires minimal ground cover in October and November.

The third management focus will be on carbon, though the conversion of thinned trees to biochar. Carbon sequestration is an important part of climate change prevention and mitigation. When a tree decomposes, most of the carbon it contains is respirated back into the atmosphere. In contrast, biochar is a durable form of carbon that can last a thousand years. To turn the thinned trees into biochar, I will cut and pile the smaller diameter branches to be burned the following year. The trunks and larger limbs I will let lay on the forest floor- these parts are insect habitat and provide other ecosystem functions. When it is time to burn the piles, I will try a few established methods (cone pit, trench, kiln), which I will reflect on in my results. Increased carbon in the soil also improves water holding capacity and promotes microbial activity, likely benefitting the trees.

The final management focus will be on fertility. Some forests have micronutrient deficiencies which can negatively impact the health and productivity of the trees. For example, most soils in Iowa have poor Boron, which is important for chestnut production. Some of my sites have been historically overgrazed, which may have hurt the soils. I will do soil testing at each of my sites, and then apply nutrients as needed.

Research

After observing yellowbud hickory (Carya cordiformis) trees for a few years, I noticed that the most productive trees were usually open-grown or on forest edges. Dense forests produced far fewer nuts from 2022 to 2025. In some cases I harvested more nuts from a single tree than 10+ acre forests composed of around 25% yellowbud hickory. I don't have a full understanding of why this occurs, but I have a few hypotheses. First, nut predation could be higher in forests, perhaps because mice and squirrels have more protection from predators. I don't think this can fully explain my observations, because predation by deer or squirrels leaves evidence behind, which I haven't seen to an extent that explains the gap. Second, the trees could each be getting fewer resources, particularly sunlight, in settings with a dense canopy. Third, masting behavior could be more pronounced in forests because trees are more able to communicate and share resources through root connections and mycelial networks. Perhaps groups of trees in forests "decide" to exhibit strong masting behavior to starve predators, interrupt parasites such as the hickory weevil, or meet some other objective I don't understand. If I were a full-time researcher, I might study each of these mechanisms individually. As a farmer, I'm asking: can I get those trees to produce more harvestable nuts? Can it be done cost-effectively? As an environmental steward, I'm asking: will my management enhance, or degrade, ecosystem function?

My management plan is fairly simple: give the trees everything they want- sunlight, water, and nutrients. Most of this work has been conducted on two 10-acre areas, one owned by neighbor and another by my late grandfather. The first step is thinning. in 2025 I began cutting down the trees that were most heavily competing with yellowbud hickories. This will make the conditions of the forest interior trees more similar to forest edge trees, with much more sunlight. To be conscious of preserving ecosystem integrity, I tried to leave a variety of species in the stand, and avoided cutting mature oaks.

The thinning process left me with a lot of slash. Slash piles are rodent habitat, which could mean more nut predation. If left to burn or decompose, they would also release a substantial amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. To solve these problems, I came up with an efficient way to turn the smaller branches (up to 5" diameter) into biochar. Biochar has useful properties as a soil amendment, including water and nutrient regulation. The carbon it contains is stable for long periods of time. I applied the biochar under the hickory trees. After the slash piles were taken care of, only the trunks and large branched remained. Many of these were left cross-slope to decompose, provide insect habitat, and help prevent erosion. Some were cut and used for firewood.

The last thing on the trees' wish list was nutrients. I conducted soil testing at 10 different sites where hickories were present. Each site was within 10 miles of Holbrook, IA. The nutrient levels were compared to those recommended for pecans by Mississippi State University. The nutrient deficiencies were fairly consistent across the sites, with most lacking enough zinc, phosphorus, and sulfur. Boron was within the acceptable range, albeit at the lower end. Potassium levels were sufficient, and magnesium and calcium levels were much higher than recommended.

A peer recommended that I get tissue samples analyzed for a closer insight into which nutrients the hickory trees aren't getting enough of. I will do this in the second year of this project. Until then, I'm only fertilizing with human urine, and only where I have applied biochar. Urine contains nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus, so it may help with my phosphorus deficiency. Raw biochar needs to be "charged" with nutrients somehow before it is applied, otherwise it can absorb nutrients from the soil. For this reason, I apply urine to the biochar after it is spread out under the hickory trees. I keep track of how much char and urine has been applied under each tree. My rough target is 100-200 gallons of biochar and 10-20 gallons of urine per tree. In year 2, I'll test the soil under these trees to see whether the phosphorus levels have increased, if the pH changed, and if anything changed with the other nutrients.

Yellowbud Tree Biochar and Fertilizer Application

After the trees had been given everything they wanted, it was time to consider my needs. In order to efficiently harvest nuts, I need a relatively clean forest floor. The main obstacles here were honeysuckle and multiflora rose. Fortunately, those are both invasive species. Removing them would not only help me, it would help the native species of the forest. My main tool for this job is the pulaski. Digging out these plants is a good way to make sure they won't resprout. In areas that were really thick with multiflora rose, I mowed once with a small tractor and brush hog first. For the really big honeysuckle plants, I cut them off at waist height with a chainsaw when they were flowering. I'll finish them off later if that didn't kill them. I don't want to tear up the soil too much with machinery because there are ramps and wild garlic and morels and all sorts of other delicious things out there. Using hand tools also lets me discriminate which shrubs I remove. I'm ok with gooseberries as long as they aren't right where I'm harvesting. I'm also ok with prickly ash. Unlike other shrubs in this forest, it has an upright growth form. This means I can harvest nuts around it without too much difficulty, especially the big ones that look like small trees. Also, both gooseberries and prickly ash have edible parts that I like to eat. Finally, leaving some native shrubs might help discourage the invasive ones from coming back. My thinning work means that more light will be reaching the forest floor, which encourages brush growth. I'd rather that growth be species I can get along with.

I'm also experimenting with the use of fire to manage brush and facilitate nut harvest. This isn't feasible at my late grandfather's property, but I have done small burns at other sites. So far, it appears that low-intensity fires do not harm mature yellowbud hickory trees. In 2026 I hope to conduct larger burns at the properties where there is sufficient fuel.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

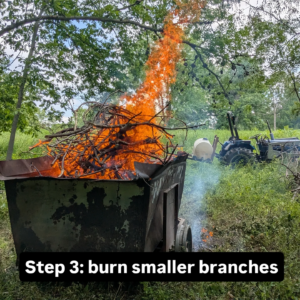

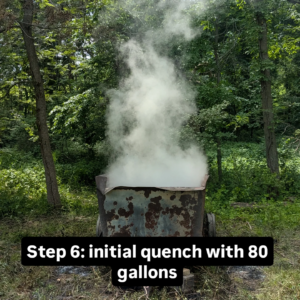

While most outreach activities are planned for 2026, I did make an Instagram post about my biochar setup in 2025. This included a series of pictures showing how I used a steel wagon with steel wheels as a biochar kiln that could be moved with a tractor for easy access and distribution. It also included a breakdown of my labor hours for that day.

...

I said I'd get better at biochar... and I did!

375 gallons in a 2.25-hour burn isn't too shabby!

I'm doing work with biochar as part of a grant with @ncrsare . I'm exploring ways to manage forests for both conservation and nut production - and biochar is a great way to meet both of those goals.

Many conservation projects involve burning brush piles. Making those piles into biochar instead saves a lot of the carbon from going into the atmosphere (mitigating climate change) and provides a useful soil amendment.

Biochar in the soil:

-increases organic matter

-supports microbial life

-helps soil hold more water

-improves nutrient availability

I'm thinning out some of the trees that compete with oaks and hickories in the forest. Then I turn their branches into biochar and apply it under the nut trees. Over longer periods of time, I'll observe whether these trees produce nuts more abundantly and/or reliably. (I bet they will!)

The last slide is my labor summary for the day, all hiccups and delays included.

6/9/25

Biochar

375 gallons

8:00- 6:00: 10 hours total, 2.25 hours burning

Summary:

8:00-9:30: gather tools, hook up wagon and water tank to tractor, check tractor tire pressure and fluids, drive 3 miles to work site

9:30-11:30: move piles closer together, in position to throw into wagon quickly

11:30-12:00: drive wagon into position, unhook and chock wheels, prep for burn, eat a bite

12:00-2:15: start fire, burn brush piles

2:15-3:00 initial quench, drive wagon to nearby hydrant and finish quenching with hose

3:00- 5:30: drive to trees and apply, counting number of buckets applied to each tree. Delays here moving logs out of the path for tractor to get through.

5:30-6:00: pack up, drive home, rinse out wagon.

Learning Outcomes

The four main activities I pursued with this work were tree thinning, brush management, biochar making, and tree fertilization. In year one, I had great success with thinning and biochar production. While I initially used a roughly 150 gallon fuel barrel to make 100 gallons of biochar over a period of 6 hours, I was able to upgrade to a metal wagon on steel wheels that could make 375 gallons in just over 2 hours. The wagon enabled me to leave branches cut fairly long (up to 9 feet), which saved time when processing the trees after they were cut down. It also made it easy to pile the brush near where the trees were felled, and facilitated transportation of the finished char.

In year 1, I conducted brush management manually and with fire. Manual removal of honeysuckle and multiflora rose with a pulaski was effective but labor intensive. I did not have much success with burning. I tried to burn in the early fall before the nuts fell, hoping that the fire would help clear the ground to make harvesting easier. However, the fuels were too wet at this time to burn at the sites I wanted to burn. Fescue grass was the dominant species at these sites, which stays somewhat green into the fall and winter. I will continue trying to burn these areas in the spring and fall of next year. In other areas with full or near-full canopy, there were insufficient fuels to conduct a burn. I am hopeful that fire can be incorporated into productive hickory savannas in the future, because it is a chemical-free brush control method that has other ecological benefits. While some sources say that Carya cordiformis is not a fire-resistant species, I have seen no damage in trees over a year after they were burned around with a low-intensity fire.