Final Report for FNE14-799

Project Information

We completed a study to find alternative bedding sources for a composted bedded pack barn. We had hoped to find a low cost alternative to wood shavings or sawdust. While the Clean Cow Bedding performed remarkably well during the summer and was more cost effective than the sawdust, we struggled with it during the cooler months. Overall, sawdust remains the best bedding type for use in a composted bedded pack barn.

Introduction:

Composted bedded pack barns offer an innovative solution to the problems of nutrient management, manure storage, and cow comfort. A composted bedded pack barn is a loose housing system that consists of a deep bedded pack that is actively going through a rapid decaying and composting process. Sourcing cost effective bedding is a significant problem for farmers transitioning to a composted bedded pack barn. Cornell University researchers cited the access to affordable bedding as the largest obstacle to adoption of composted bedded pack barns. This study looked at three different readily available bedding treatment types and compared it to the control of saw dust.

Identifying alternative bedding sources for composted bedded pack barns is important because this style of housing has the potential to substantially increase the environmental and financial sustainability of small dairy operations through facilitating better management of nutrients and enhancing milk production through increased cow comfort. Through proper management of nutrients, farmers can increase crop yield and quality, yet many small farms lack the infrastructure to manage their nutrients during the winter. A composted bedded pack provides manure storage for the farmer and allows her to apply nutrients to the field based on the needs of the soil. Composted bedded packs also provide a lower cost method for small farms to update their infrastructure from traditional tie stalls.

Research into composted bedded pack barns has demonstrated that adequate bedding, frequent aeration, and proper ventilation as the three most critical management concerns affecting the functioning of the composted bedded pack. Frequent aeration is achieved through tilling the pack to at least 10” twice per day. Most farms use cultivators or chisel plows pulled behind a small tractor or pushed by a skidsteer. Proper ventilation is achieved through either passive means like siting the barn to take advantage of prevailing winds or active means like properly positioning high power fans to draw water from the pack.

While aeration and ventilation concerns are thoroughly addressed in multiple extension resources and the SARE database, cost-effective bedding sources are not identified. The information regarding bedding sources that does exist demonstrates that the bedding material must have small particle size to facilitate composting activity through providing a substrate for microorganisms and to prevent entanglement in tillage equipment. Bedding material needs to have high lignin content so that it does not break down quickly or dissolve when saturated. The bedding material must also be very absorbent.

Farmers in Minnesota and New York identified sourcing cost-effective bedding as the most significant hurdle in transitioning to composted bedded pack barns. The need for affordable sources of bedding is echoes in the action of producers in Madison County, NY who have tried to adopt composted bedded pack systems but have either had to transition back to free stalls or to deep bedded pack barns.

The objective of this project was to measure the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of alternative bedding materials in a composted bedded pack barn. We tested Clean Cow Bedding (Cassella/EarthLive product: a fiber based bedding alternative that is a pH adjusted blend of thermo-mechanically processed virgin wood fiber, cellulose fiber, lime and clay ), peanut hulls, and peanut hulls mixed with woodchips. We chose these materials because we thought they had suitable C:N ratios and would be effective at composting. Prior to testing the experimental beddings, we established the composted bedded pack following the Minnesota Extension guidelines and tested the pack for a temperature of at least 107 degrees Fahrenheit to determine the presence of biological activity. We divided the barn in half, with one side receiving a control treatment of sawdust and the other side receiving the experimental treatment. We tilled the pack and added bedding as needed, depending on the weather and other factors. We cleaned out the pack in May and October.

We had hoped that by establishing the pack correctly we would be able to remove pack death as a confounding variable. Unfortunately, the pack was much more sensitive than we anticipated during the cooler months and maintaining biological activity in the pack was a significant stumbling block. We had hoped to stick with each treatment for four months, but none of the treatments lasted for a full four months due to either cow health concerns or pack health concerns. In 2014 and 2015 we maintained the pack with a c-tine cultivator pulled behind a Ford 9-N and in 2016 we maintained the pack with a rototiller pulled by a Farmall 300.

We measured bedding temperature to assess biological activity weekly and performed a chi-squared test on the results. We had initially intended to measure cow activity, but this metric was bulky, so we moved to an anecdotal observation system.

We did not find it efficient to spread based on the different treatments applied to the pack, so we stockpiled the manure in the freezer for a final analysis. We have sent the samples for nutrient analysis and will be posting the results in the future.

The primary goal of the study was to identify a bedding material that was more cost effective than woodchips or sawdust. We kept track of the cost of the bedding and the time it took to go through the bedding. We also tried to capture externalities of the different bedding types through noting the time, fuel, and wear and tear on the pack tiller and any exceptional impacts on herd health, specifically mortality, cow lameness, and cell count. We were not able to capture bedding preference in our observation, so we could not include that in our financial analysis.

Cooperators

Research

We kept the initial experimental design of comparing an experimental treatment to sawdust in 2014 and 2015, but in 2016 we moved to bedding the entire barn with the experimental bedding and comparing that to the barn expansion with the control bedding. When we started the grant, we did not expect to be expanding so quickly, but using two separate barns for the two distinct treatments was much more effective than splitting one barn in half because we didn’t have a zone of blending.

While we were conducting treatments, we tried to measure the temperature on the pack one a week. We had initially proposed that Saturday would be the day that we measured the temperature on the pack but those became challenging days to collect data, so we moved to including it during part of regular chores during the week. While we did not maintain one specific day of the week for collecting temperature data, I don’t believe that this added a substantial amount of variability.

We also recorded noteworthy cow activity, lameness, and noteworthy herd health events throughout the duration of the experimental bedding treatments. We recorded noteworthy cow activity during our usual daily barn observations and also recorded noteworthy health events like lameness, mastitis, and mortality.

We took pack samples for a nutrient analysis and had them analyzed. Unfortunately, the samples never made it to Cornell. We reserved subsamples and will be sending them to Cornell with the next courier, but the results will not be back in time.

We recorded the cost of the bedding types and the amount of time it took to go through the bedding along with noteworthy herd health events. We used this information to create a financial analysis of the three different experimental bedding treatments and the control. The financial analysis was more precise but less accurate than we anticipated. By including the herd health events, we were relying on correlation to indicate causation. While it was possible that they were related and needed to be included in the financial analysis, it was also possible that they were no related and wrongfully impacted the financial analysis. Due to the fairly small size of the experiment, the financial analysis was also way too sensitive to externalities.

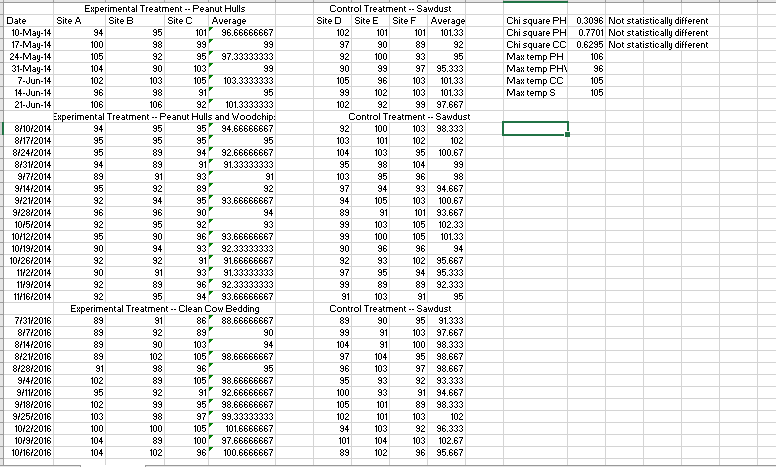

We measured the temperature of the pack every week in order to approximate the biological activity on the pack. The maximum temperature of the pack never exceeded 106 degrees Fahrenheit, which means that we were never able to truly compost the material in pack, although we did see enough biological activity for some breakdown of the material. We performed a Chi-squared test on the temperature data to see if any of the treatments had a statistically significant different level of biological activity in the pack. The Chi-Squared test found no statistically significant difference between the any of the treatments and the control.

We did notice some interesting behaviors on the pack. The cows really enjoyed eating the peanut hulls; this behavior seemed to disappear when we mixed the peanut hulls with the woodchips. We also noticed some herd health issues disappeared when we mixed the peanut hulls with woodchips. When we used the Clean Cow bedding, we noticed that the bedding really lived up to its name. While our cows have a typical baseline level of cleanliness, their coats shined up nicely when we used the bedding. With the exception of some minor stone bruising caused by the old farm road during the Spring of 2014, we did not experience any lameness in our herd during the course of the study.

The results from the nutrient analysis have not yet come back and will be posted at a future date.

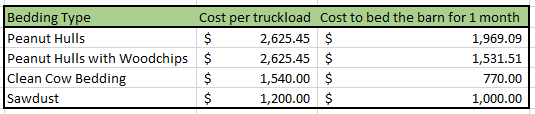

We completed the financial analysis based on how much the material cost and how quickly we went through the material. While the sawdust was the cheapest per truckload, the Clean Cow Bedding was the cheapest per year because we used it at a slower rate than the sawdust. The peanut hulls were by far the most expensive per truckload and the most expensive per month.

A table showing the cost to bed the barn with different bedding types

A table showing the cost to bed the barn with different bedding types

Based strictly on the financial analysis, it would seem that the Clean Cow bedding was the most effective bedding type, but there were other factors that played into our bedding choice. The Clean Cow Bedding worked really well in the summer. The cows seemed to enjoy it, the animals stayed very clean, and the barn stayed dry. Once the weather got cooler and the cows started to spend more time in the barns and we had to till the pack more frequently, the Clean Cow Bedding did not provide the structure needed to support the skidsteer or the 300. Without the ability to get onto the pack to till it, the pack died and turned into a soupy mess.

While we had hoped to identify a type of bedding that would be more cost effective than saw dust, the cost, physical structure, and absorbant characteristics of the saw dust make it the most cost effective bedding choice.

We have not had any farmers adopt a composted bedded pack system because of our research, but we have had farmers who were thinking about adopting composted bedded pack systems visit our farm and then subsequently adopt bedded packs.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Our outreach plan involved hosting a tour of our composted bedded pack and creating a video and fact sheet. As predicted, our tour was only moderately successful. 27 people showed up for the tour, of which 21 were actively engaged in agriculture. Our farm tour had good publicity, including a mention in Morning Ag Clips. In addition to providing a tour of the barns and discussing our preliminary results, we also hosted a panel of speakers including an expert from Cassella Organics, the Farm Business Management Specialist from Oneida County, the Ag Subject Educator from Madison County, and an Loan Officer from FSA. We created a Fact Sheet based on our preliminary findings for the farm tour and it is attached to this report.

While 21 active farmers did attend the farm tour, we also reached farmers through e-mail, farm visits, and phone calls. We have fielded e-mails and phone calls from seven different farmers about the results of our studies, hosted two farmers for personal tours, and have one farmer scheduled for a tour. We have tried to be as open about our results as possible and really enjoy sharing our composted bedded pack barns with other farmers.

We also created a video. The video did not turn out to be as effective as we had hoped, but it does contain the information that we learned during our research project.

Project Outcomes

Potential Contributions

A composted bedded pack barn can definitely be a very positive housing situation. It is low cost, easily adaptable, and has allowed us to build a healthy herd. In the last three years, we have experienced no lameness in our herd and have not struggled with somatic cell count.

Seasonal variation seemed to be one of the biggest challenges in managing the pack. It was fairly easy to keep the pack at least partially alive and dry during the warmer months, but during the cooler months it was a challenge. The structural support of the pack became more important during the winter, as the bedding was not able to support the tillage equipment and the cows struggled a bit with it. I think that finding a bedding material with proper structure is the next step towards finding the best type of bedding material.

Future Recommendations

While peanut hulls and fiber bedding were not as universally successful as saw dust, pursuing further research on the Clean Cow bedding may definitely be worthwhile. There is also a need to identify sources of bedding that aren't sawdust. Corn stovers, peanut hulls, chopped hay/straw are all alternatives that do not work to keep a composted bedded pack alive, but there has to be some other waste material readily available in the Northeast that could be used for bedding a composted bedded pack barn.