Final report for FNE15-816

Project Information

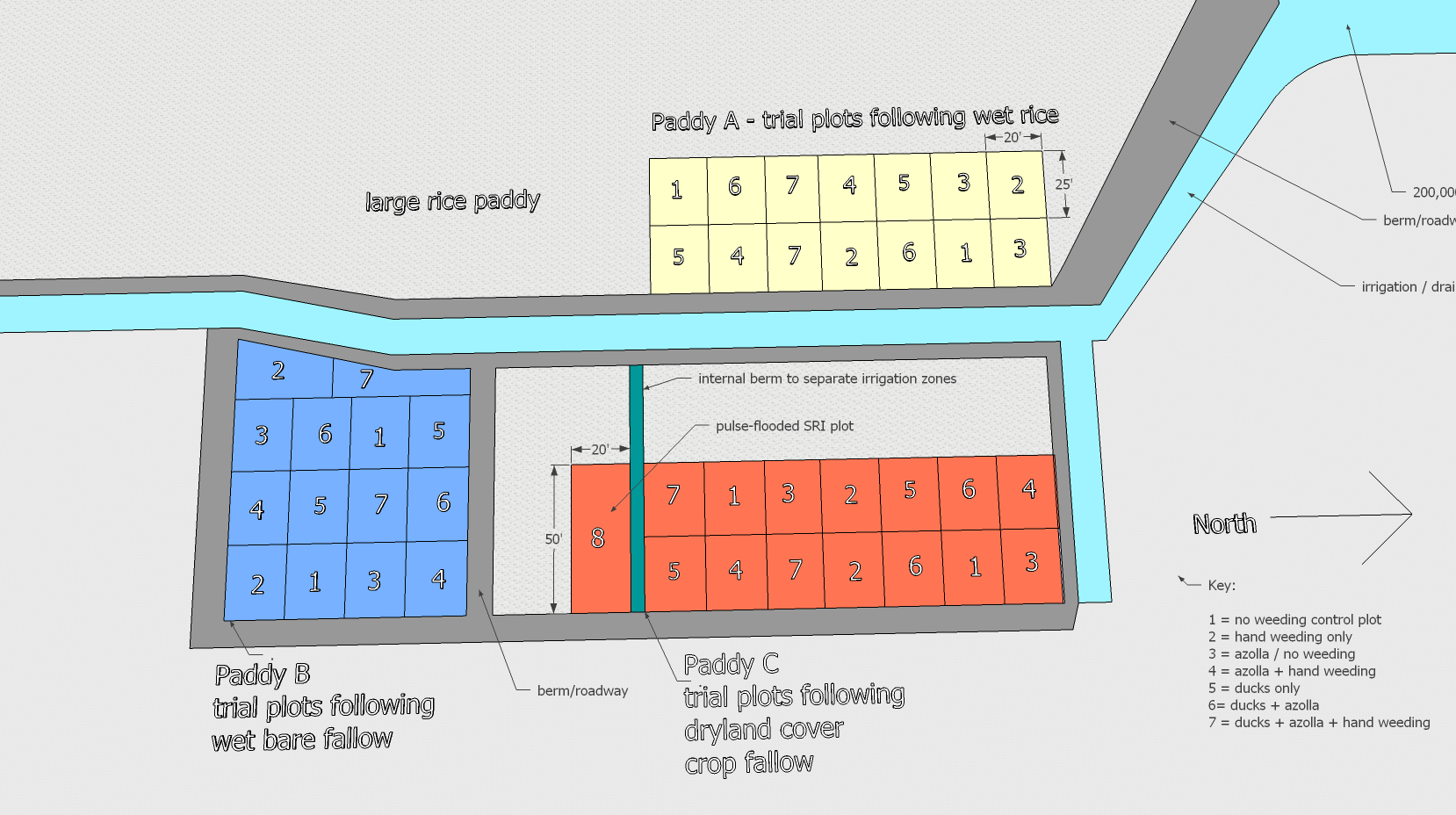

Our aim was to evaluate weed control strategies for wet rice cultivation. Erik Andrus served as lead farmer and project director, and Ben Waterman of the UVM Center for Sustainable Agriculture is technical advisor. Groundwork for the trial was laid in 2015 by establishing prior-use patterns in three different rice growing zones. In 2016, the main work of the trial took place, and several different modes of weed control were compared, including a control, hand-labor control only, and the use of weeder ducks managed according to the Japanese "aigamo" method. Additionally, we experimented with the use of azolla as a floating smother crop and with the use of specialized mechanical weeding equipment. We found that azolla carolinas growth was mercurial in nature each year and not dependable though promising so we may source it from a region with a similar climate.

We evaluated our techniques according to a metric of pounds of production recovered per hour of human labor spent in weed management, with labor allocated strategically over a 6-week weeding season. Hand control only was found, unsurprisingly, to be a costly approach, recovering between 1.17 and 1.97 pounds of rice production per hour. Duck plots with no human weeding labor were between 10% and 100% more productive than hand-labor only plots in terms of total production, and consumed negligible human labor. Plots with weeder ducks and supplementary hand weeding were the most productive plots and required much less time to keep fully weed-free than hand-labor only plots.

This evaluation shows the impact of several weed control method on the annual productivity and labor requirements for small-scale rice operations. We have shared our results through a farm visit, grower consultations, and through publication of our full report and distribution through UVM extension.

Our objective is to perform trials of the most promising techniques of ecological weed control. Over the course of two years we aim to evaluate the comparative costs and benefits of weed control using multiple strategies, measured against a control. We aim to measure the labor and other associated costs of weed control methods against gains in productivity.

These trials must take place over two consecutive growing seasons to gauge the impact of fallowing prior to planting. Fallowing has an entailed cost in that a season of potential production is forfeited, and we aim to assess whether the benefits outweigh that cost.

Additionally we will trial the effectiveness of weed control with ducklings (a common Japanese organic method), with floating cover (azolla filiculoides) and through hand control both in a continuously flooded paddy and in a pulse-flooded paddy, using a minimal-irrigation and mechanical weeding strategy known as SRI (System of Rice Intensification).

Following transplanting, all but the pulse-flooded trial plot will all be kept flooded with 4 inches of water until the ripening phase begins (August) but will be managed for weed control using seven different methods.

Plots 1 and 8 (Control #1) will receive no weeding. Reasonable effort will be made to prevent azolla from entering the plot, using a plastic barrier.

Plots 2 and 9(Control#2) will also not receive azolla but will be hand weeded until canopy is established (mid-July).

Plots 3 and 10 (Azolla#1) will be seeded with azolla immediately after transplanting but will not be hand weeded.

Plots 4 and 11 (Azolla#2) will be seeded with azolla immediately after transplanting and will be hand weeded until canopy is established.

Plots 5 and 12(Ducks#1) will receive 4 ducklings (approximately the stocking density recommended by Takao Furuno) one week after transplanting but will not be seeded with azolla or be given manual weed control

Cooperators

Research

We aimed to lay out three field areas with different prior-year treatments to evaluate the impact of prior year usage. These were areas were Paddy A, in which rice was grown with weeder ducks as normal in 2015, Paddy C, which was not planted in rice in 2015 but instead was kept flooded with several inches of water and was wet-tilled (or "puddled") at regular intervals, and Paddy B which we attempted to maintain in a dryland state and plant with cover crops. The plan to repeatedly till and replant dryland cover crops was altered somewhat in Paddy B because wet early summer conditions kept the field very wet despite our efforts to treat it as a dryland field.

Going into 2016, all three fields were puddled and planted with akitakomachi rice seedlings on June 16th. One week after transplanting, the plots were subdivided as indicated in our plot plan. Water depth was maintained at two inches for the first week. On June 24th the experimental plots were subdivided with stakes and string. Plots containing weeder ducks were also divided with nylon netting.

Over the course of the growing season, we managed rice crops in several different ways in order to assess the costs and benefits of different organic approaches to weed control.

In spring of 2016, all fields were puddled. The last tillage of the fields occurred on June 14th, two days before transplanting. At time of transplanting, the water depth was 1-2 inches. Paddies A, B, and C were all transplanted between June 16th and June 17th. On June 24th the water depth was increased to three inches and ducks were added throughout the site in plots labeled 5, 6 and 7.

At this same time plots 3,4, and 6 were inoculated with azolla, but this had fairly little effect due to limited azolla supplies and azolla plant vitality that I will discuss further in "outcomes and impacts."

By June 28th the ducklings had made a noticeable impact on their plots and weeds were quickly emerging among the crop in areas without ducks. On June 28th we began our regimen of hand weeding and continued it in plots labeled 2, 4, and 7 until August 5th.

By August 5th the plants had developed full canopy and weeding was no longer needed. The ducks were removed from the field and surface waters were drained off. Rainfall was sparse in late summer and fall, and by harvest time, all areas were dry and firm.

On October 1st the grain was ripe and ready for harvest. We harvested each plot separately and weighed the resulting yield. Over the course of the project we also tracked the time invested in weeding and in monitoring the weeder ducklings. I am still in the process of compiling all this data, but will be ready to present it in 2017.

Two unexpected events altered the experiment. The first is that we were unable to get our crop of azolla to thrive during the month of June. Our azolla is azolla caroliniana, native to the Carolinas, and is ordered from an aquarium supply outfit. In both years we ordered two pounds of live plants and attempted to multiply them by growing them in a shallow pond in the farmstead. In 2015, it was slow to grow in May and June but began developing in July. In 2016, growth seemed even slower and by July 4th we did not have enough to effectively deploy azolla as a weed control measure, yet by that time weeds were growing apace.

Using azolla as a floating weed control smother crop was problematic because weeds seemed to gain the upper hand before azolla can become thick enough to suppress them. In 2015, in Paddy C and also in some other fallowed paddies, we had good luck filling large areas with azolla. But in 2016 the azolla seemed to barely grow.

In mid 2015, I had the opportunity to travel to Japan and visit with farmers in the north and south of the country who use non-chemical weed control, primarily relying on weeder ducks. The use of azolla is well described in Japanese farmer Takao Furuno's book "The Power of Duck." However I did not see anyone using azolla along with the ducks. One farmer in Hokkaido, Yoshikazu Orisaka said that he had trouble establishing azolla even using heated water and greenhouses and had basically dismissed it as unnecessary for adequate fertility and weed control.

Another factor is that when ducks and azolla are used together, there is a tricky issue of timing. The azolla needs mid-season heat and sunlight to multiply but the ducklings seem to consume the azolla faster than it can grow, at least during the first two or three weeks that ducks and azolla share the paddy. Ultimately, for purposes of weed control, azolla seems to have at least minor compatibility issues with the use of weeder ducks, that are not apparent from a reading of "The Power of Duck."

The ultimate effect of the weak azolla performance was that the azolla only plots (3) closely resembled the control plots in performance, the azolla plus hand-weeding plots (4) resembled the hand-weeding only plots (2), and the plots with ducks and azolla (6) performed similarly to the plots with only ducks and no azolla (5).

The second setback was that we aimed to valuate a minimal-flooding strategy as an added investigation in the area market plot 8 in Paddy C. We tried to keep this area hydrologically isolated from the adjoining area. However seepage from the neighboring plot through the division dike was such that the plot repeatedly filled with one or two inches depth, keeping the ground perpetually soft. Weeds grew extremely profusely in this plot but the soft, sticky clay made effective cultivation between rows very difficult. Weeding tools balled up with clay and feet sank deep into the mud. The rice also underperformed fully flooded rice.

We have now completed our first year prior-usage plan, and our field trials. What remains is to compile and analyze the data and to try to draw useful conclusions from it in terms of resulting yield and the costs incurred to attain that yield.

We maintained a control plot, which became rife with weeds and had negligible yield. Absent a chemical approach, growers need a coherent strategy for weed control, clearly.

In general, we were able to evaluate azolla, the use of weeder ducks, and the use of hand and mechanical weeding in wet rice. While azolla presented challenges that seemed to limit its effectiveness as a method, the use of weeder ducks, and hand and mechanical weeding remain vital. Having some numbers to gauge their relative merits will surely help us going forward, and I hope this will help other growers and aspiring growers too.

Initially, the methods I had intended to compare were as follows:

- Control - Flooded but not weeded

- Flooded and hand weeded

- Flooded and containing azolla but not weeded

- Flooded and containing azolla and hand weeded

- Flooded, with ducks, but not weeded

- Flooded with ducks and azolla and not weeded

- Flooded, with ducks and azolla and hand weeded

- Pulse-irrigated SRI method

Revisions to Design

The Paddy C area was intended to have a prior year usage of a dryland cover crop. This might have worked in a normal year but rainfall was so heavy in June and July that the field could not be worked. We did manage to plant one cover crop of winter rye late in the season but it performed poorly.The second development that led us to change the design was the mercurial nature of our azolla species. Azolla is a floating fern that behaves a little like duckweed, but is a nitrogen fixer. As such it has great potential to add fertility to rice systems. However we found it hard to predict how it would grow. It seemed to grow very rapidly in certain situations and shut down in others. Cool temperatures (below 65 degrees) resulted in almost no growth, but hot temperatures with lots of sun seemed to also result in the leaves turning red and growth shutting down. I have since learned that Azolla is very sensitive to phosphorus shortages in the water, and that may have had something to do with it.

Also, I had been growing a species of azolla caroliniana. I have since learned that this species is one of the more difficult to manage. In the future I hope to try out azolla filiculoides, which is native to the Pacific Northwest. All azolla species are 100% winter killed in a climate like vermont so the risk of introducing them to the local ecology is nil.Interestingly, during my visit to the Japanese Duck Rice conference, I saw no azolla either at Takao Furuno’s farm or at other participating farms. I did ask about it and several farmers had tried it but found it too difficult to manage. The general sense I got was that azolla has potential but adds too much complexity, and the general duck-rice system works adequately well for growers yet remains within their management capability.

Due to troubles managing it at home and the lack of interest in it I witnessed in Japan, I made the decision to eliminate the azolla variable from the trials, this greatly simplifying the experiment. I set out to compare hand weeding alone, ducks alone, and ducks and hand weeding against each other.Each plot was 25’ x 30’, or 750 square feet, 0.017 acres. We compared management methods from the time of transplant (June 20th) to the time of full canopy formation (August 7th), assessing resulting yield, which was separately harvested and weighed, and labor inputs into the project during the trial period.

The pulse-flooded trial was also eliminated from the experiment due to difficulty managing the separate water levels enough to permit foot traffic for the kind of weed management SRI proposes. I decided that a serious evaluation of SRI was beyond the scope of what I could manage within this experiment.Evaluating Results

Since I was chiefly interested in managing labor and increasing yield, I divided pounds of plot yield by hours of labor to yield a factor that represents the labor efficiency of the competing methods, and applied a qualitative description of the degree of weed suppression.|

FNE 15-813 Field Trial Results |

Control |

Hand Weeding |

Ducks Only |

Ducks and Hand Weeding |

|

|

Following Rice and Ducks |

Yield, lbs |

2.00 |

28.10 |

31.00 |

36.00 |

|

Labor |

0.00 |

14.25 |

0.00 |

5.00 |

|

|

Lbs yield / labor |

n/a |

1.97 |

n/a |

7.20 |

|

|

Weed Suppression |

Very Poor |

Good |

Very Good |

Very Good |

|

|

Following Wet Fallow |

Yield, lbs |

5.00 |

15.50 |

29.20 |

34.00 |

|

Labor |

0.00 |

13.30 |

0.00 |

5.50 |

|

|

Lbs yield / labor |

n/a |

1.17 |

n/a |

6.18 |

|

|

Weed Suppression |

Very Poor |

Good |

Very Good |

Very Good |

|

|

Following Cover Crop |

Yield, lbs |

2.90 |

18.50 |

26.00 |

29.80 |

|

Labor |

0.00 |

12.50 |

0.00 |

8.80 |

|

|

Lbs yield / labor |

n/a |

1.48 |

n/a |

3.39 |

|

|

Weed Suppression |

Very Poor |

Good |

Very Good |

Very Good |

The control plots yielded very poorly with the rice plants largely choked out by barnyard grass. Hand weeding plots out-yielded the control plots at the cost of copious amounts of hand labor to keep them clear. But yields in the duck rice plots topped the hand-weeded plots, presumably due to the constant agitation of the water and the presence of duck manure.

The pounds of yield gained per hour of labor is an important number, because depending on how highly the farmer values their time, it simply may not make economic sense. In all the hand-weeding only trials, the amount of production gained by hand weeding is between one and two pounds of rough rice gained per hour of work. Especially when one considers additional work and loss of crop weight in harvest and processing, it is hard to imagine this labor investment paying off. Perhaps in a traditional village agriculture system it might be worthwhile, from a survival standpoint, for a person to pull weeds all day to increase the production by fifteen or twenty pounds because that is still a considerable energy gain, considering the person would only eat one of those pounds during the day it took to do the work. But from a dollars and cents standpoint, the calculation is simply brutal--the rice grown simply cannot pay an hourly wage unless the crop is priced exorbitantly.Duck plots where supplementary weeding took place (far right) were the best yielders in the trial, and consumed fewer hours of labor than plots with hand weeding alone. An hour spent weeding in the duck plots resulted in greater gains of production than in the hand labor only plots. However duck plots without hand labor were also respectable.

Further Thoughts on Weed Control

During the trial, additional ideas came forward about how to weed more efficiently either alongside ducks or in the absence of ducks. Several ideas have come forward. The first is the use of small motorized or nonmotorized walking cultivators. I devised one out of a Mantis rototiller by fabricating a small boat to it, that was narrow enough to thread between the rice rows. It worked great, so long as the weeds were small and the mud fairly loose and well flooded. It would ball up with large weeds.

A further improvement on this concept is the use of a string trimmer with a boat arrangement as an inter-row weeder. I have recently discovered this made-in-Japan attachment to a straight shaft trimmer but have not had a chance to try it yet. It has a blade that attaches to the trimmer shaft that whips through water and mud. It seems that this would offer all the advantages of my homemade Mantis arrangement while also being lighter and performing even better. It costs about $200.

Looking at the entire rice season, weed control is clearly one of the main concerns for growers. If you can get a solid method that delivers good production for effort invested, you are well on your way to setting up a successful operation. I had inclination towards the duck method prior to embarking on the trial and the results have confirmed this.

I would highly encourage any prospective Northeastern rice farmer to acquire a copy of The Power of Duck directly from the publisher. But here are some of the key highlights of the duck method:

- About 100 ducklings per acre, but subdivided down to plots no larger than 50 ducklings to 0.5 acres.

- Ducklings should be hatched around the same day as transplanting is done in order that they be around 10 days old when introduced to the rooted, transplanted field

- Survival of the ducklings depends on them being able to fluff and dry themselves as needed. Each fenced zone should have an easy ramp out of the paddy and some shelter. Feed the ducklings daily here to encourage them to come there

- Constant vigilance is needed to discourage predators. Trap, hunt, fence them out, whatever it takes

- Water level should be rather low when ducklings are first introduced, and may need to be decreased if there is a very hot spell, but can usually be increased up to 4”-5” after a few weeks and stabilized there. In general, the deeper the water, the better weed control, but not so deep as to drown your plants

- Ducks are removed from the paddy when plants begin to ripen (usually early to mid August).

Our intention as farmers and in writing this report is to progress towards a coherent approach to small-scale rice growing, considering scale-appropriate methods and devices for the key rice-growing chokepoints, notably transplanting, weed control, and harvest. We compiled this accompanying visual overview of comparitive methods.

Seasonal Labor Requirements per Acre

These figures are roughly based on labor inputs that we have tallied here over time. For instance, an acre of crop required about five hours per week through April and May, increasing to maybe ten as the field is prepared for transplanting. But if transplanting is done by hand, labor requirements increase to 80 hours per week in June. However if a machine transplanter is used, per acre labor is only about 20 hours.

Starting in the second half of June, the acre grown using hand labor alone requires 90 hours per week of work. The beige column shows how maybe, with the implementation of good weeding devices, this might be reduced to 45 or so hours per week. But the farmer using ducks for weeding only spends about 15 hours per week per acre during this phase, mostly light labor monitoring how well the ducks are doing their job.

In August, work drops off for all farming approaches as there isn’t much to do as the crop ripens.

Starting in October another labor issue emerges as the farmer using hand methods has to put in a lot more hours than the one who can deploy a combine.

The general picture is that hand-labor only operations may be difficult to make viable, even with their products priced at top dollar. But it is certainly within the realm of the possible. However with the addition of ducks, the annual labor picture of hand labor operations is considerably better. We have also found that with appropriate-scale equipment for transplanting, harvesting and milling we have been able to get work done smoothly enough to be able to contemplate undertaking additional fields.

This is a challenging field of agriculture, adapting a crop that is very well understood elsewhere to our landscape and cultural context, and nobody should expect it to be smooth or free of surprises. It is a good domain for those who enjoy solving puzzles and drawing information from a variety of sources. And, not least of all, quality rice is a rare delight in the U.S. food marketplace. Apart from people who have lived in Asian countries with strong traditions of local growing and milling, most Americans are not accustomed to finding delight in a bowl of rice. It is a special honor for a farmer to be able to open this world of experience to neighbors, and to begin to make a place for this ancient and venerable food in our landscape.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

In August 2016 I participated in a farmers' discussion panel related to rice growing in the Northeast at the Kushi Institute in Massachusetts, in which I described our efforts relating to these trials. In Feburary 2017 I began to present the results of our field trials at a workshop session at the NOFA Vermont winter conference. A .pdf copy of my presentation is available as an information product.

In July, 2017 I offered a farm field day demonstrating machine transplanting and giving visitors a tour of our duck-rice weeding system in action in partnership with Vermont Land Trust.

I have performed two onsite farm consultations, one in Ulster Grove, New York and another in Mequon, Wisconsin.

Additionally I have had produced a series of three short films detailing our rice growing practices, which are now freely available on YouTube. The first episode can be found at this address: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UCVc73LKWB8&t=34s

I have written a booklet of 47 pages describing the context and methodology of small commercial scale rice growing in the Northeast. This is available as a SARE digital product and from me directly as well.

Learning Outcomes

Currently rice growing is just getting going in the Northeast, with only a few serious adopters. So my number is limited to those who are already engaged in rice growing and are looking for answers as to how to grow more rice with less effort, to whom I have reached out over the course of this work, of which there are six including myself. There are an additional four farmers that I have communicated with who are considering growing rice and are interested in methodology.

Project Outcomes

The most notable outcome from my perspective is gaining a better understanding and control over labor demands from rice systems over the course of the season, and as a result I have become better at allocating hired help and better at managing my own time. I am less likely to throw my time at strategies that have a low return for effort, as revealed by the research.

As a by-product of doing this work I have developed a connection with the ecological rice farming community in Japan, which has already yielded important and timely technical information relating to the duck rice method, rice agronomy, and technical questions. It is difficult to access this information across a language and cultural barrier but I have become motivated to learn Japanese in order to better access the vast reserves of information and experience related to rice in that country.

Our advances with rice systems helped our farm provide good consulting advice for other aspiring rice farmers, and encouraged them to invest in rice systems. My technical support for the Marquette Univerversity small commercial temperate rice project was critical in securing a $35000 grant to the Biology Department in April, 2017. Additionally, our ability to help plan and support the planned expansion of Evergrowing Family Farm's rice project in Ulster Grove , New York helped them raise $3000 from their local community.

Our experiment initially considered too many variables and had to be revised over the course of the project. However, once this was done, it did produce some meaningful numbers. In general I feel that the labor savings of the duck method have been proven to be meaningful. It is still possible that azolla culture could be meaningful too, but I have been unable to assess this yet. I hope to continue to research azolla in the years to come.

While in general the ability of ducklings to suppress weeds is clear, their ability to fertilize crops is somewhat more limited. Takao Furuno found that ducks deliver about 20lbs of nitrogen to the acre over the course of the season. That quantity is well below the 50 lbs of additional N considered adequate to attain yield potential. But Furuno theorizes that because the duck rice system optimizes plant uptake, this lesser quantity of N is adequate and soils also are improved year by year.

In our operations, even our best plots seldom attain the yield levels common in organic operations in Japan and the poorest plots are much inferior. I have found that obtaining weed control and some fertility with ducks simply does not build a productive system overnight if the starting soil is very poor, as many of our plots are stripped of topsoil as a result of the paddy creation excavation process. I am guessing that the duck rice system will work to slowly improve or to maintain growing systems without addition of soluble fertilizer during the growing season, but that for very poor or damaged soils, other fertilization strategies may be called for. I am now working with UVM extension to develop a rice soils improvement plan and a crop fertilization plan to work in concert with our annual duck-rice weed control practices.