Final report for FNE18-891

Project Information

In this study we tested the comparative weight/feed cost ratio of pigs on good perennial pasture with and without an added protein supplement in their ad lib feed. Our intent was to begin to fill the knowledge gap regarding effective sustainable protein additive levels in modern pastured pork to insure the most economically and environmentally sustainable feed compositions. The study was conducted for four weeks and consisted of three groups of 9 pigs each eating either (1) full hog finisher, (2) cracked wheat with mineral and lysine, or (3) cracked wheat and mineral only. Paddocks were chosen that gave the pigs unlimited and equal forage access, with many varieties of forage rivaling canola meal in crude protein (~33%). Pigs were weighed before and after the study period and their gains analysed alongside the amount of feed each group consumed over the four weeks. The average cost/lb of weight gained for each group was then analysed. The group fed cracked wheat with a mineral and lysine supplement was found to have the most economical cost/lb of weight gained at 64 cents/lb as compared to the full feed and cracked wheat with mineral groups at 76 and 73 cents/lb, respectively. Therefore, managing pigs on diverse pasture while providing small grain with lysine and without protein meal (such as soy or canola) promises to be the most effective method. More exact and varied testing must be conducted however, and this study shows the potential merit in such testing.

The purpose of this study was to determine if hogs on protein-rich pasture without a protein additive (such as soy or field peas) in their feed would have decent gains compared to a control group on the same pasture with a full hog feed. Gains are likely to be somewhat slower, but the cost/benefit analysis of gains vs. feed costs may indicate that good pasture without the use of added feed protein is the most efficient option. Pastured pig operations could save a significant amount of money on outside protein sources during pasturing season, making their operations more financially sustainable in a market that only allows for very thin profit margins. Well-managed pasture will reduce the amount of bought-in monocultural protein sources as well as conserve local farmlands and increase soil fertility.

In the first half of the twentieth century it was known that pigs on good pasture would make healthy gains on small grains and mineral alone, without the use of a protein supplement (Thompson and Voorhies, Cal. Bul. 342; Osland and Mortan, Colo. Bul. 381; freeman, Mich. Quar. Bul., 15, 1933, No. 4; Joseph, Mont. Bul. 236; Headley, Nev. Bul. 175; Wilson and Wright, S. D. Bul. 262; Smith and Maynard, Utah Bul 254.) Gains were somewhat slower but feed conversion was typically good. Little research has been done on this topic since, and several things have changed: 1) today’s pigs are longer, faster growing and leaner than pigs back then, requiring relatively more protein, and 2) supplemental amino acids are now available which can fix a protein balance deficit.

The purpose of our study was to determine if hogs on protein-rich pasture without a protein additive in their feed would have decent gains compared to a control group on the same pasture given a full hog feed. Gains of pigs given grain without a traditional protein supplement were likely to be somewhat slower, but we hypothesized the cost/benefit analysis of gains vs. feed may indicate that good pasture without the use of added feed protein is the most efficient option.

We feel this research is relevant as positive growth rates from the pastured pigs on wheat & mineral alone or wheat & mineral with lysine would allow farms the option to maintain protein-rich forage instead of buying in protein supplements from industrial, monocultural operations from other regions. Utilizing intensive pasture rotation would increase local biodiversity, soil fertility, and insure farmland be preserved and used in a sustainable fashion. Very little research has been done in pastured pigs since the rise of industrialized pork. However, more and more people are becoming interested in smaller scale, pastured operations--due to environmental sustainability, animal well-being and superior meat nutrition. Small pig operations do not have much information on pasture nutrition available to them, and have to contend with a lot of continuous costs. We decided to conduct this experiment to shed light on how smaller operations can most effectively raise their hogs on pasture.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

Research

- Methods

a. Specifics:

3 groups of mixed heritage/commercial breed hogs consisting of 9 hogs in each group were fed three different ad-libitum feed mixes (one group per mix). The mixes were as follows:

- Wheat and mineral mix: WM

- Wheat, mineral mix, and lysine: WML

- Wheat, mineral mix, lysine, and GMO-free canola meal: WMLC

Each individual pig will correspond with their respective group acronym (WM, WML, WMLC) in all results, as well as their individual tag number.

Pigs were weighed with a Waypig 500, which has an expected accuracy of within three lbs. All pigs were determined to be healthy at the beginning of the study.

All pigs were wormed using fenbendazole for (5) days two weeks prior to the study start time to insure parasites would not be a factor. Each group of pigs were given 2 acres of perennial pasture consisting of native and non-native common pasture plants, containing about 85% preferred hog forage. The three groups’ were randomized so that the starting weights of each group averaged around 156 lbs (with ~2 lb. differential). Each group had 6-7 “heritage cross” pigs and 2-3 “commercial cross” pigs. All study pigs were of 5-6 months of age. They were sorted, tagged and given roughly two acres of vegetation each (separated by two polywire strands) from August 28th to September 25th, 28 days total.

Feed consumption was calculated assuming the number of 50 lb. bags used during the experiment. We assumed 20% feed loss in each group due to the nature of our feed choice system (open bins), which was affected by rain, trampling and mud and had to occasionally be dumped and replaced. All groups had equal access to clean feed. Water was free choice, and each group had one 75-gallon tub, which was replaced daily. All pigs had equal access to hedgerow and wallows for weather protection and temperature regulation.

- Hog Selection

a. Hog Genetics

Two sources of hog genetics were used in the experiment. The first was pigs farrowed on-farm. This line of pigs was started by crossing a purebred lard-type Mulefoot boar to purebred commercial Duroc sows. 50/50 Mulefoot/Duroc sows were crossed back to a purebred Gloucestershire Old Spot boar. Future generations were crossed to boars containing Hereford, Yorkshire and Berkshire genetics. At that point the herd was closed and all selection happened from within the herd. Primary selection criteria for both boars and sows were 1) maternal instincts for open pen farrowing, 2) confirmation and growth characteristics and 3) temperament. All hogs selected from this source are labelled “heritage cross” in table 5.

The second source of hogs was bought in from another breeder. These pigs were yorkshire & duroc crosses- a more commercial hog. They are labelled “commercial cross” in table 5.

Table 1: Feed Recipes & Costs

|

WM(1) |

WML(2) |

WMLC(3) |

|||||||

|

Ingredient |

Cost per pound |

Amount per ton, lb |

Subtotal |

Amount per ton, lb |

Subtotal |

Amount per ton, lb |

Subtotal |

||

|

Wheat |

$0.09 |

1950 |

$175.50 |

1938 |

$174.42 |

1576 |

$141.84 |

||

|

GMO-Free Canola Meal |

$0.28 |

0 |

$0.00 |

0 |

$0.00 |

370 |

$101.75 |

||

|

Mineral Mix |

$0.30 |

50 |

$15.00 |

50 |

$15.00 |

50 |

$15.00 |

||

|

Lysine |

$1.00 |

0 |

$0.00 |

12 |

$12.00 |

4 |

$4.00 |

||

|

Labor & delivery |

$60.00 |

$60.00 |

$60.00 |

||||||

|

Cost per ton |

$250.50 |

$261.42 |

$322.59 |

||||||

|

Cost per pound |

$0.13 |

$0.13 |

$0.16 |

||||||

|

|||||||||

|

2. Wheat, minerals, and lysine. |

|||||||||

|

3. Wheat, minerals, lysine, and GMO-free canola meal. |

|||||||||

- Pasture/Forage Analysis

a. The Pasture Sward

Paddocks were chosen that gave the pigs unlimited forage access in a best case scenario for a perennial pig pasture. We originally planned to graze the research pigs on a mix of brassicas and Durana white clover, but experienced a drought during the first half of the season which stunted their growth, and found the brassicas to be less competitive than pre-established species. We then switched our focus to naturally occurring perennial pasture, which is what we and most other known operations use to graze anyway. The field chosen had been rotationally grazed with pigs 2-3 times per season for 8 years. The grazing has always been done with high stock density (300 hogs averaging 150 lbs per ¼ acre - 180,000 lbs of pig per acre) and short duration (1-4 days per paddock). The field was not mowed in this time.

The study began in the paddocks on August 28th after a dry spring/early summer and a wet late summer. The field was grazed in May and June and was allowed to regrow until the start date, a regrowth period of about 75 days. The vegetation was lush but “overmature” for making high quality hay. The goal was to give them essentially unlimited forage. At the end of the experiment plentiful high quality forage remained in the paddocks.

Pasture composition was typical of rotationally grazed hog pasture - high plant diversity, consisting of a variety of annuals and perennials and including nutrient-loving annuals (lambsquarters). The most commonly found plant species included perennial grasses, white clover, red clover, dandelion, curly dock, burdock, morning glory, lambsquarters, redroot pigweed, chickweed, canada thistle, milkweed, goldenrod and asthers. While there was some variation, paddocks were largely similar in their forage variety make-up.

A diverse pasture sward is ideal to suit the grazing nature of hogs. Through our observation during this study and over the years of pasturing pigs, we’ve seen pigs are high selective in their grazing habits (unlike cattle, for instance). As they walk through the paddock, they may take a single bite of curly dock, then eat a young thistle, and then a dandelion leaf. They prefer the lower fiber broadleaf “weeds” to grasses generally, although they have a technique for maximizing the value of grasses. The hogs will take a mouthful of grasses, masticate them, drink the juices and spit out the fibers into a “puck”. This allows them to get the highly digestible water soluble sugars and proteins without filling up on relatively indigestible fiber. The highly selective nature of hogs allows them to always find forage at an acceptable stage of maturity and avoid overmature or fibrous forages.

Photo: a ball of grass fibers after a pig has chewed it at length.

Generally speaking, they graze rather than root, although localized rooting was observed, mostly around colonies of Canada Thistle, which spread through rhizomes. Interestingly, the rooted up areas provide surface soil access for the seeds of the very annuals and biennials that the pigs prefer - dandelion, lambsquarters, etc. The rooting also encourages regrowth of canada thistle shoots - a preferred, high protein forage.

b. Forage Testing and Analysis

Observation of the pigs showed that their preferred forages were white clover, curly dock, dandelion, chickweed, lambsquarters, canada thistle and young grasses. Samples of each of these plants were collected from the actual paddocks the pigs were grazing during the experiment and sent for forage testing. The forage testing clearly showed that the available forages provided high quality, high protein fodder.

It should be mentioned that in addition to the plant varieties below, a negligible amount of fallen tree nuts and fruits (acorns, black walnuts and wild apples) were also accessible within each group’s paddocks. Our analysis also does not include nutrients obtained via rooting such as tubers or grubs, which we speculate provided some additional protein and minerals.

Table 2: ESTIMATED % OF PASTURE COVERAGE, BY VARIETY OF FORAGE

|

HIGHLY DESIRED: lambsquarters (hogweed): 10% clover: 10% curly dock: 5% dandelion: 10% canada thistle: 5% chickweed: 10% morning glory: 5% . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . total: 50% SOMEWHAT DESIRED: grasses: 35% . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . total: 35% NOT DESIRED: milkweed: 5% burdock: 8% goldenrod: 2% . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . total: 15% |

Table 3: NUTRITION COMPOSITION OF PREFERRED FORAGE

|

Plant Species |

Part Collected |

Crude Protein |

aNDF |

Relative Feed Value |

|

Curly Dock |

leaves |

34.9 |

28.5 |

239 |

|

Morning Glory |

vines and leaves |

28.8 |

32.4 |

203 |

|

Canada Thistle |

young plants |

33.4 |

41.6 |

152 |

|

Dandelion |

leaves |

27.0 |

40.0 |

138 |

|

Chickweed |

stems, leaves and flowers |

25.1 |

35.8 |

172 |

|

Lambsquarters |

leaves and immature seed pods |

19.8 |

30.4 |

212 |

|

Young Grass |

leaves |

31.4 |

42.9 |

141 |

*conducted at Dairy One Labs, 730 Warren Road, Ithaca, New York 14850

- Results

Separating the means using orthogonal contrasts showed that WML-fed pigs gained significantly faster than WM-fed pigs. However, WMLC-fed pigs were not different than the average of WM- and WML-fed pigs, as seen in Table 4:

|

Diet(1) |

Final weight(2), lb |

ADG(2), lb |

|

WM |

192 |

1.24 |

|

WML |

201 |

1.55 |

|

WMLC |

199 |

1.49 |

|

SEM |

3.2 |

0.117 |

|

1. Pigs fed WMLC did not differ from the average of pigs fed WM and WML, but pigs fed WML gained more (P = 0.056) than pigs fed WM. 2. Adjusted by covariance analysis to a common starting weight of 157 pounds. |

||

Pigs given a full finishing feed (WMLC) had the best feed conversion, but made the most expensive gains due to the higher price per lb of feed. Pigs given wheat and minerals with supplemental lysine (WML) on good pasture converted feed nearly as well and made by the far the cheapest gains per lb. Pigs given wheat and minerals (WM) had the worst feed conversion and an intermediate cost per lb of gain.

Table 5: Final Analysis

|

Item |

WM(1) |

WML(2) |

WMLC(3) |

|

Number of hogs in the group |

9 |

9 |

9 |

|

Number of hogs in final analysis (4) |

8 |

7 |

9 |

|

Average starting weight (5), lb |

159 |

156 |

157 |

|

Average final weight, lb |

194 |

196 |

198 |

|

Feed consumed (6), lb |

1636 |

1338 |

1760 |

|

Gain, lb |

282 |

275 |

372 |

|

Feed/gain |

5.8 |

4.86 |

4.73 |

|

Cost of feed per lb |

$0.13 |

$0.13 |

$0.16 |

|

Feed cost per lb of gain |

$0.73 |

$0.64 |

$0.76 |

|

|||

|

2. Wheat, minerals, and lysine. |

|||

|

3. Wheat, minerals, lysine, and GMO-free canola meal. |

|||

|

4. Pigs who were considered "Poor-Doers" were removed from the analysis. This was defined as pigs that were two standard deviations below the group average of "Gain in 28 days as a % of starting weight". Two were offered the WML diet and one was offered the WM diet. |

|||

|

5. This and following rows only include hogs included in the final analysis, not the slow growing "poor doers". |

|||

|

6. Pounds of feed consumed was assumed to be divided evenly among all pigs in the group. At the end of the experiment each group had several bags of feed left in the hopper and feeding the pigs in the open troughs led to considerable waste through spillage and rain damage. We are assuming based on these observations that each group wasted or didn't consume 20% the feed offered. |

|||

There was a large variation in the performance of individuals in any group. Pigs that grew at two standard deviations below the mean rate of gain, which was ranked by the percentage of weight gained by each hog as a percentage of its starting weight, were excluded from the primary analysis as they were “poor-doers” and presumably had an unknown health issue causing the slow growth. Two pigs were excluded from group 2 and one pig from group 3. Table five shows every individual including the excluded pigs.

Table 5: Pig Rank by Weight Gain

|

Tag Number |

Beginning Weight |

Genetic Background |

Ending Weight |

Group |

Weight Gain |

Gain as % of Starting Weight |

|

9 |

160 |

commercial cross |

214 |

WMLC |

54 |

33.75% |

|

2 |

150 |

commercial cross |

196 |

WML |

46 |

30.67% |

|

2 |

170 |

heritage cross |

220 |

WMLC |

50 |

29.41% |

|

5 |

157 |

heritage cross |

202 |

WMLC |

45 |

28.66% |

|

4 |

171 |

heritage cross |

220 |

WML |

49 |

28.65% |

|

5 |

154 |

heritage cross |

197 |

WML |

43 |

27.92% |

|

7 |

150 |

heritage cross |

191 |

WMLC |

41 |

27.33% |

|

7 |

152 |

heritage cross |

192 |

WM |

40 |

26.32% |

|

2 |

167 |

commercial cross |

210 |

WM |

43 |

25.75% |

|

6 |

168 |

heritage cross |

210 |

WMLC |

42 |

25.00% |

|

3 |

160 |

commercial cross |

200 |

WMLC |

40 |

25.00% |

|

6 |

144 |

heritage cross |

180 |

WML |

36 |

25.00% |

|

8 |

153 |

heritage cross |

190 |

WMLC |

37 |

24.18% |

|

10 |

152 |

heritage cross |

188 |

WMLC |

36 |

23.68% |

|

3 |

158 |

heritage cross |

194 |

WML |

36 |

22.78% |

|

3 |

145 |

heritage cross |

178 |

WM |

33 |

22.76% |

|

8 |

146 |

heritage cross |

178 |

WM |

32 |

21.92% |

|

6 |

152 |

heritage cross |

184 |

WM |

32 |

21.05% |

|

8 |

165 |

heritage cross |

199 |

WML |

34 |

20.61% |

|

9 |

170 |

heritage cross |

205 |

WM |

35 |

20.59% |

|

1 |

152 |

heritage cross |

183 |

WML |

31 |

20.39% |

|

5 |

174 |

commercial cross |

209 |

WM |

35 |

20.11% |

|

4 |

140 |

commercial cross |

167 |

WMLC |

27 |

19.29% |

|

1 |

167 |

heritage cross |

199 |

WM |

32 |

19.16% |

|

*** Pigs Excluded from Analysis *** |

||||||

|

4 |

150 |

heritage cross |

175 |

WM |

25 |

16.67% |

|

9 |

170 |

heritage cross |

188 |

WML |

18 |

10.59% |

|

7 |

155 |

commercial cross |

171 |

WML |

16 |

10.32% |

Each group had a commercial cross pig as one of its top two performers and one of its bottom two performers (there were only two or three commercial cross pigs in each group of nine). The heritage cross pigs were significantly more consistent. The standard deviation of commercial cross pigs weight gain as a percentage of starting weight was 5.7% and the standard deviation of heritage cross pigs was 3.3%. The commercial cross pigs likely have higher genetic potential for gain but are more prone to health issues since they were introduced to a new farm as piglets and may be more prone to disease pressures that the on-farm born pigs are adapted to.

Photo: The excluded pigs continued to underperform their peers after the conclusion of the experiment when all of the pigs were returned to the finishing herd. Shown in this image is one of the excluded pigs - WML number 7, red pig in the center of photo - laying between its peers from the experiment. This picture was taken Oct 23rd - 28 days after the experiment concluded. Its appearance is sickly and thin. Excluded pigs later had to be culled due to wasting.

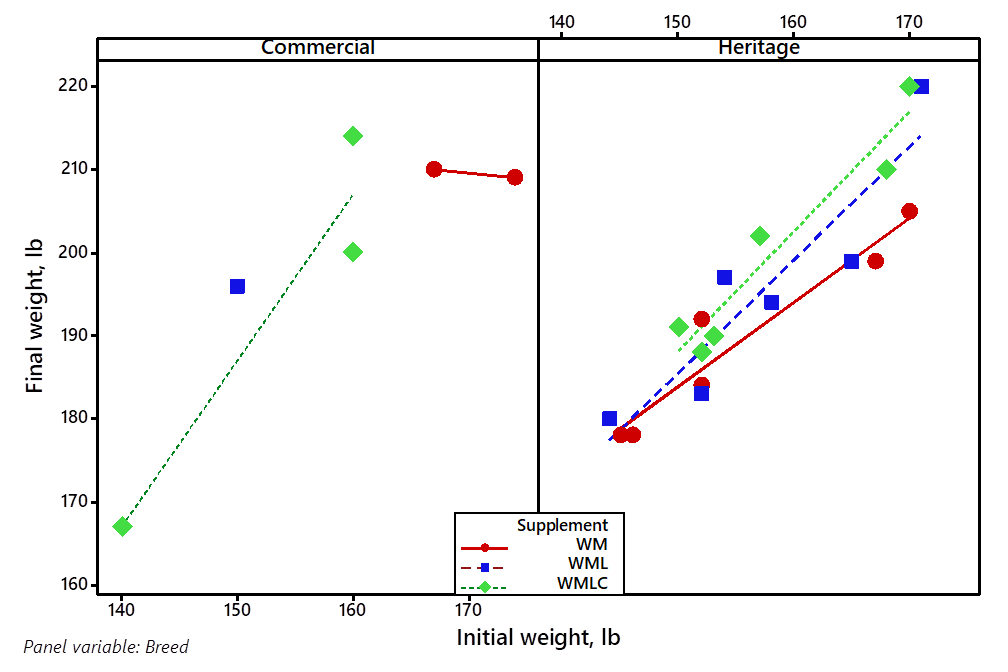

Table 6: Starting Weight Vs. Finishing Weight

Table: Final weights adjusted by covariance to an average initial weight of 157 lb were 192, 201, and 199 ± 3.3 lb for pigs supplemented with the WM, WML, and WMLC diets, respectively. Pigs supplemented with the WMLC diet on pasture grew (ADG = 1.5lb/d) at the same rate as the average of the pigs supplemented with the WML and WM diets (ADG = 1.5 and 1.2 lb/d, respectively); the SEM for ADG was 0.09 lb/d. Pigs supplemented with the WML diet, however, grew faster (P = 0.056) than pigs supplemented with the WM diet.

As expected, giving pigs an ad-lib, full diet feed proved to have the best feed conversion. However, pigs given ad-lib ground wheat supplemented with a vitamin/mineral blend and lysine performed as well and made significantly cheaper gains. Forage analysis of the plant species most preferred by the hogs showed that the crude protein levels in their preferred forages rivaled that of canola meal (~33%). It is reasonable to think that hogs are able to forage enough crude protein to supplement what is lacking from ground wheat, as suggesting in Morrison’s Feeds and Feeding. Lysine is known to be the first limiting amino acid in all grains for growing hogs and is not likely to be found in sufficient quantities in forage crops to supplement the lack from cereal grains. Ground wheat plus minerals plus lysine proved to be the near equal of using an expensive protein supplement (canola meal) but at much cheaper cost. The crude protein in the forages is replacing the crude protein in the canola meal.

The results show that although giving pigs an ad-lib whole grain ration without supplemental lysine actually produced gains at a lower per-lb cost (based on feed costs alone) than fully supplemented feed, that approach is not warranted. Pigs supplemented with lysine grew faster and made cheaper gains than pigs supplemented with just wheat and minerals.

Getting exact feed conversion numbers of small groups of pigs eating out of troughs in a pasture is an inexact science at best. Grain is wasted by pigs muddying the troughs, rain soaking the feed, pigs fighting over space at the trough, etc. To try to get consistent results, we didn’t clean out troughs, and instead put new feed on top of old feed to try to get the pigs to eat everything they could and not introduce a variable of “muddy, wet feed that was thrown out”. Further complicating that analysis is the variation between individuals in a group. For instance, Group 2 had the two poorest performing hogs in the entire experiment. Should we assume those two hogs consumed the same amount of feed as the group average? Future research should focus on using systems that monitor the feed intake of individual hogs such as the FIRE pig performance testing system from Osborne Industries.

Photo: Open troughs which resulted in consumption measurement difficulties (taken pre-study, does not picture study pigs nor the study paddock).

Areas for future research include 1) optimizing forages, acreages and grazing strategies needed to supplement grains for grazing hogs, 2) selecting breeding stock that is better suited to make use of forages to convert at better rates on pasture, 3) considering the concept of limit feeding of grain-based supplements to encourage hogs to make more use of forages and 4) continuing to study adding or removing supplements for pigs on pasture that could improve performance or minimize costs without a loss of performance including amino acids, vitamins and minerals.

This avenue of research is greater interest to organic farming and Non-GMO certified farming since feed cost savings are multiplied by the price of the feeds. At current feed prices, for project Non-GMO verified feed, using wheat supplemented with lysine reduced production costs by 12 cents per lb versus a full protein supplement. In an organic production setting, using wheat supplemented with lysine could reduce costs by 33 cents per lb.

Picture: Study Group 1/ WMLC Group, grazing.

Picture: Study Group 2/ WML, grazing.

Picture: Study Group 3/ WM, grazing.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

An on-farm demonstration was conducted mid-study to allow public accessibility to the running study and to answer questions that participants had. Research will be publically posted on the www.thepiggery.net educational page. Once our final study is approved by SARE, we will submit it to the NOFA organization for their newsletter, as well as the NY Pork Producers Newsletter and the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group. NESAWG (Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group) has agree to publish our findings in their newsletter as soon as it's ready. NOFA NY has been contacted about publishing in their newsletter.

Learning Outcomes

Farmers who gained knowledge and further interest include Brad Marshall and Angela DeVivo (The Piggery Inc.), Kerry Hollier (Hollier Farms), Devon Van Noble (Van Noble Farms), and Mark Justh (J&D Farms), as farmers involved or consulted during this project. The study suggested pastured pig operations can benefit from small grain feeds without supplemental protein added, and will experience nearly similar gains to hogs fed full finisher if lysine is included in their feeds. This offers both economic and environmental benefits to farmers currently pasturing their pigs in the form of lessened feed costs. Therefore, intensive grazing is not only an appealing method to enhance meat nutrition and quality of life, but also to reduce overall input costs. This is a fairly new concept to modern pastured pig farmers.

Project Outcomes

Our results offer potential for both increased economic gains for small farmers as well as incentives for environmental conservation. We will be experimenting (hopefully with an additional grant for more accurate testing) on our own farm with feeds with reduced or omitted crude protein supplements, as will our associates and other farmers in our community, such as Van Noble Farms, J & D Farms, and others.

Our infrastructure provided much of the necessary requirements for such a study. In light of what we learned, a more accurate way of measuring feed consumed is needed. The open bins we used resulted in some feed loss, making our results less accurate than we'd like.

We feel additional studies are needed but that we answered the question presented, mainly: is there potential for good pastured pig gains using reduced or no-protein feeds? Yes. We look forward to this study being published and for more in-depth studies to be conducted.

Organic and non-GMO pig farmers in the northeast and beyond would benefit from the information resulting from this study. We hope this study, in addition to aiding currently pastured pig farmers, may offer economic incentive for other hog farmers to take an interest in pasturing their animals and abandoning confinement practices.