Final report for FNE18-897

Project Information

FNE18-897 Hanson Full report Jan 27, 2020

ABOVE, SEE FULL REPORT WITH UPDATED PHOTOS AND SUMMARY OR AT

https://3streamsfarmbelfastme.blogspot.com

At 3 Streams Farm, I (Shana Hanson) have been practicing pollarding and harvest of tree growth to feed livestock since 2011 with guidance from international literature sources and contacts. To "pollard" is to "prune drastically above browse height, cut close to their head on top of a clear stem" in order to re-harvest the new growth every 3 to 6 years for fodder. For this study, we created a Demonstration Plot of one acre and observed trees already pollarded and continued creating a full acre of managed tree fodder with the help of Josh Kauppila, Emily MacGibeny and other helpers, by harvesting tree canopies of a mixed species 55 yrs. growth woodlot (which was lightly managed in multi-aged continuous cover for firewood 1963 to 2011). We used ladders, ropes and harnesses, hand saws and sometimes chain saw, with Pruning Rules based upon above observations to transition the acre into a Demonstration Plot of “air meadow” fodder production.

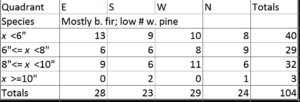

In the Demonstration Plot, red maples are more numerous among the 300 (+/-) retained trees than all other species combined, followed (most to least numerous) by white ash, quaking aspen, balsam fir, white birch, red oak, yellow birch, beech, white pine, big toothed aspen, hemlock, and white cedar. Trees (excepting two much larger white pines, retained intact) measured from 13 ½” to <2” Diameter at Breast Height (DBH, averaging 6”) (we did not record the trees <2”), and were pollarded at heights varying from 6’ to 63 ½,’ with cut tops 3’ to 48’ in length, 2.82” average top cut diameter, and averaging 20.7 yrs. old (ring count) at top cut.

We timed our labor to be 604 person-hrs./acre, which included tight intricate felling of most firs before starting the pruning of canopies, very slow setting of climbing ropes by us amateurs, and piecing and stacking of brush throughout.

1,216 lbs. dry matter (DM) per acre were eaten within the Demo Plot by a small herd of dairy goats (averaging 7 individuals) during this transition harvest, with unexpected significant amounts refused by this highly selective animal group. Dried leafy branch refusals by the goats were brought to hogs on-farm or to sheep at Y Knot Farm), plus about 95 gal. of silages and about 30 armloads of fresh and dried leafy branches removed for sampling at all farms were not measured. If fed to most appreciative Meadowsweet Farm beef cattle and sheep, these refusals and removals would likely have yielded 300 more lbs. DM edible portion/acre, giving a loosely estimated total of 1,500 lbs. DM edible portion/acre, or about one half the average Maine hay yield that year (and the wasted hay in feeding is unfairly not being considered here).

Subsequent harvests of 4 to 6 yr. old sprout-wood will be more palatable than these initial 20 yr. old tops, according to 3 Streams Farm goats and established pollards.

Winter storage methods of on-site stacking, chipping and drying, and container-ensiling both chipped leafy branches and hand-stripped leaves (usually leaf bunches with basal twigs), were trialed with about 20% mold or caterpillar damage observed (at leafy center tarp openings) in on-site horizontal stacks but 0% damage in Jackson Regenerational Farm’s vertical stacks, 0% mold in chipped dried species other than aspens but about 90% mold observed in chipped dried aspens, and about 3% (seemingly edible) mold observed at air leaks in silages.

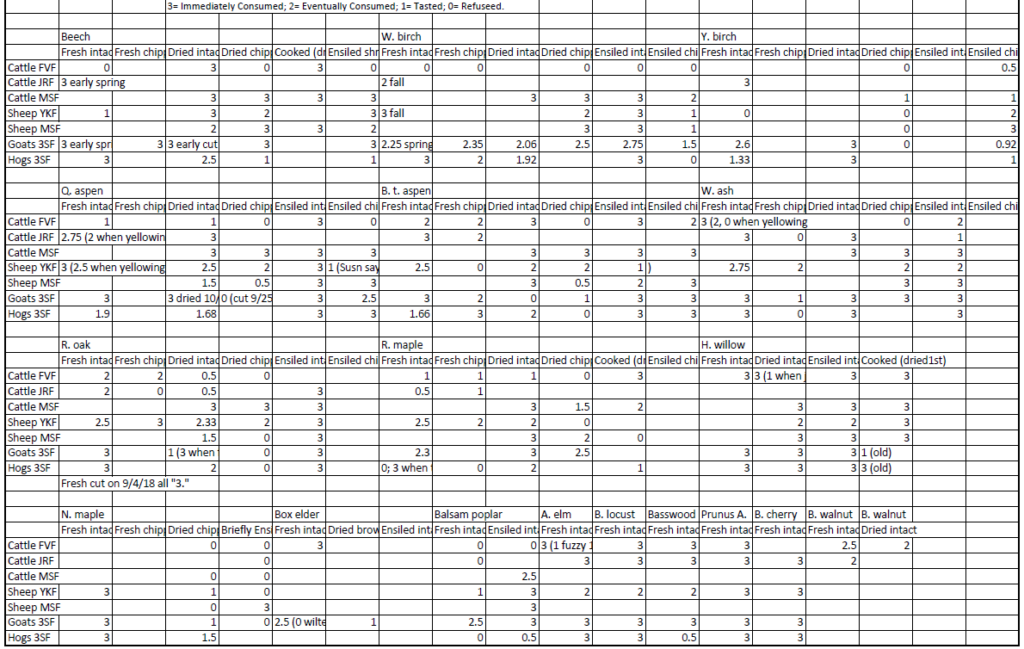

Cattle, sheep, goats, and hogs at 6 farms sampled fresh leafy branches both intact and chipped, and above forms of stored fodders of 15 tree species, plus cooked dried leaves of 8 species, with more than two thirds of offered samples accepted: 52% of 740 samplings rated by observation as “immediately consumed” and another 19% rated as “eventually consumed,” versus 12% “tasted” and 17% “refused.” Summary tables are offered here within, and the full data spreadsheet can be viewed at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BgOksabfTq1hBPmraRYBzED8lCQOGTgV/view. Some photos are included below, and more photos and short videos of sampling by livestock can be viewed at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Hd2de-xm5kvkXO7iNGNMNZ5zyL8AUzkI and https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/12E1tICQo-sMrZ3EE650-VYGXKMTlnZEU.

We expect 92% of demo plot trees to become productive healthy fodder trees on existing trunks. All white ashes produced large dark green heads of sprouts, mostly at or near cut locations. Red oaks sprouted strongly along their previously bare trunks as well as on and around branch stubs or collars, then were about 98% defoliated in mid-summer by insects. Most quaking and big toothed aspens started with particularly small canopies on tall trunks, and reverted to prolific root sprouts, which can be developed into more accessible understory pollards. Most white birches were similarly proportioned, and stayed alive but with little new growth. Red maples, the most numerous species, varied in sprouting strength with health possibly related to water access during the 2018 4th drought summer, or to sun exposure winter 2018-19 when fluctuating temperatures caused unseasonably repeated sap runs; season of canopy harvest, and tree age or height were not observed to correlate with strength of sprouting.

Tree sprouting responses both of Demonstration Plot trees and of established pollards outside the Demonstration Plot were photographed and correlated with photos before and after canopy harvest. Some photos are included here within, and all can be viewed at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/12dmc3K7kTklG-RHQ3m3S2erO8BC3ggtE.

Pollarding guidelines with species-specific comments are offered below, recommending ideally 3" diameter cuts in wood in young wood no more than an arm’s reach from the trunk, and prioritizing trees that start with good health, low branches and full canopies, for economy of form that supports sap flow reaching sprout locations.

I have presented about our study at 9 outreach events in 4 states, reaching about 160 participants, and now have a contact list of people who want to know more about using tree leaf fodders.

We will:

- Examine our previously established pollards and document findings, to guide development of durable and fodder-productive tree structures;

- Restructure 1 acre of woodland to create pollarded ‘air meadow’ fodder canopies, prioritizing species with long seasonal windows of usage by our goats, and keeping mature tree structures as well as young trees for immediate productivity and height diversity;

- Record descriptive data for farmer woodlot comparison including initial and pruned heights, and labor time;

- Trial rough modern adaption of traditional stacking of leafy branches, record weights of summer and winter fodder eaten on the 1 acre site by goats, and compute lbs. DM/acre;

- Document goat, sheep, cow and hog responses to 8+ species of intact and shredded ‘twig-leaf’ fodders fresh, dried, ensiled, and (hogs and cows especially) dried then cooked, so that farmers can offer feeds likely to be useful to their livestock;

- Present our experiences, data, and recommendations about use of Northeastern US woodland for tree leaf fodder to regional farmers at face-to-face events and on line.

Our purpose is to trial historically common European methods of sustaining livestock with tree leaves from pollarded woodland “air meadow,” as a way to optimize carbon sequestration while securing a reliable farm-based fodder source. Our trial will offer information pertinent to Northeastern US farmers on labor feasibility and initial fodder yield, tree species specific pruning guidelines, fodder processing and storage options, and cattle, sheep, goat and hog tree leaf fodder preferences in the growing season and in winter.

I have been studying production and use of tree leaf fodders since 2011, triggered by climate irregularities, failures of annual and biennial crops, and observations of my livestock. This funded project enables me to have intern support to complete an intact area of woodland versus piecemeal patches and edges, plus commits me to pull knowledge together for others, to reach a broad audience of farmers who may benefit from this ecologically generous fodder alternative.

Droughts and floods emphasize need for climate-resilient and climate-stabilizing livestock fodder alternatives. Trees participate critically in water cycling: their transpiration moderates air temperatures and humidity, their pollen is necessary to seed rain, their root turnover (especially when pollarded) is the best preventative against soil water-logging, and in dry soil they pull moisture upward into reach of ground layer plants. Their leaf litter as well as root processes feed biologically rich soil structure which absorbs ground water, filtering and decreasing run-off. Traditional farm fields in Europe were interspersed with ubiquitous rows of pollarded trees, seen (correctly) as the sources of soil fertility.

‘Air meadow’ canopy harvest of existing woodland, and pollarding of trees in general, was historically known to increase health and longevity of the trees themselves (despite looking so hard-hit at initial pruning). And even unpollarded trees weather climate extremes more successfully than does open grassland. To pollard is to cut off the top and branches of (a tree) to encourage new growth at the top. The difference with coppicing is that trees and shrubs are coppiced at ground while pollarded plants are standard trees, cut close to their head on top of a clear stem.

“Multistrata agroforestry systems represent the highest level of carbon sequestration in food production…There is a need for development of multistrata production systems for non-tropical climates…Fodder tree silvopasture in particular is worthy of broad-scale expansion” (Toensmeier, 2016, pp.323-4), yet we have lacked regionally useful information which we now will attempt to provide.

I have farmed and provided farm labor (pruning, grafting, blueberry harvest, cow milking) since

1983, and here since fall 2000. Milk contracts plus fruit related employments provide the steadier half of my income. Demonstration pruning will replace my usual work for goats.

For this project, farm funds are set aside for shredder, tarps, bungees, contractor bags, fence posts and clips. We just bought a platform scale, and have sufficient fence wire, buckets, ropes, harnesses, two chain saws and pruning tools.

Cooperating farm information: Faithful Venture Farm in North Searsmont produces Certified Organic Holstein milk for Horizon. These cows are unfamiliar with tree leaf fodder. Y Knot Farm in Belfast sells cheese and meat from their East Freisian x Dorset sheep, plus chicken eggs, at their farm store; the sheep were taught by goats to love tree matter. Jackson Regenerational Farm in Belmont is opening woodland for a tree leaf fodder/acorn savannah raising American Guinea pork, broiler chickens, eggs, and a Dexter milk cow and Dexter x Jersey calf, who already choose leaves significantly.

Our Technical Advisor Eric Evans breeds chestnuts for the American Chestnut Society, Maine Chapter, and and tends a home fruit and nut orchard in nearby Camden.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

Research

Demo Plot Set-up

Fencing: Josh Kauppila and I Shana Hanson started this spring by surveying and fencing a 1 acre square area, in order to include presence of goats munching while we worked for extended periods. We used 5 rows of stainless steel wire I had previously ordered wholesale from a company in MA (1 cent more per foot than retail polywire at the time), with one row of white and black polywire on top for visibility. We used pieces of bicycle and motorcycle inner-tubes, with a layer wrapped onto small poplar poles, and then a strip tied around the wire then tied around the inner-tube protected pole.

The fencing held up well, with fair resilience when branches landed on it, and easy repair. The charge from a 30 mile ParMak DC charger with 10 or 15 watt panel and truck battery was not sufficient to prevent escapes when goats were offered limited leaf choices. Our habit of being tied up in trees caused delayed responses to the goats’ initial break-outs; timely training is key to having goats respect charged wire fencing. Dry ground conditions did not help, combined with the large size of paddock and tendency for moist and conducive ferns to replace themselves quickly in some moister stretches, overly grounding the fence. Therefore goats were sometimes tethered to trees near brush piles, upon which we fed them the fresh branch menu of the day.

Toward fall, offerings in the Demo Plot rose in attractiveness over those outside the fence. For one, we were getting faster at setting ropes from tree to tree, plus pruning a mix of choice species. Also the goats started accepting hay in their paddock overnight, balancing tree tannins well. Goats were contented and started feeling like the Demo Plot was home; break-outs decreased and they were tied less frequently.

Weighing Goats (to assess quantity of Demo Plot leaf fodder eaten): Josh and I brought an antique platform scale (recently purchased in Lincolnville for $300) across pasture, down the wooded bank and across the stream using a large plastic Jet sled. Josh brought a plywood platform for it; I strung a tarp fence over by the shady south gate. We soon added an internal fence separating the weighing area, as goats were gaining weight immediately at branch piles while we fetched each goat back for weighing. We did often offer them a more limited snack of browse during weighing.

The adult goats accepted weighing as required at entrance and exit times, and tended to want to continue to stand on the scale longer than necessary. The kids sometimes stuck around for this fun, but sometimes dove the fence in favor of immediate access to leafy branch piles. We occasionally let go of retrieving them, in favor of computing representative weights based on other days’ weighing data, as the kids (who were born in July and nursed most of our growing season) usually had minor to no weight changes from entrance to exit.

Restructuring the Tree Canopy

Felling, Stripping or Retaining Softwoods: White cedars and hemlocks are being retained as sources of winter fodder; I am currently pruning them toward fastigiate (columnar) form leaving about 1/3 of their greenery. Josh and I decided that balsam firs and white pines with live growth below 10 feet could be retained and topped, surviving and offering some prunable or browsable fodder value without undue shading of broadleaf pollards. I also topped and pruned a few individual firs and pines that offer ladder service to access a neighboring tall broadleaf.

The canopy started out dense with tall firs both live and dead, and a lesser number of tall young pines. These trees were often hard to extricate from canopies of broadleaf trees we are retaining. We had thought we could complete the felling of such conifers before leaf-out, but even in fall some softwood trunks designated for felling remained puzzles unsolved, awaiting concurrent pollarding of the neighboring broadleafs. Both Josh and myself attained much practice in making plunge cuts, steep diagonal trunk cuts to shorten a tree vertically piece by piece in a limited area. I also used normal notch and hinge felling to lean a tree back and forth in a small opening, dropping 8 foot lengths of trunk until the top came down.

We climbed to stub all limbs leaving no greenery on four large white pines, meaning to offer dead standing trunks to wood peckers. This is our gesture of active hope in response to the predicted approach of Emerald Ash Borers. Ash leaves are rated highly by all the livestock groups.

We have designated one grand and one decent white pine as retained full-sized “standards;” trees thus retained sometimes are designated “legacy trees” in modern forestry literature. This will challenge the north corner of our Demo Plot with undue shade (the other is near the east fence), yet even in 1756 Johann Brauner wrote about not wanting to prune certain grand trees in a pollarded woodland.

Initial Pruning (pollarding) of Broadleaf Trees:

Beech: Due to goats’ preference for beech in early spring (hogs later showed us that they want beech all summer!), and with few beech in the Demo Plot, we choose to prune in spring but leave greenery. We cut the top and each limb back to a live twig or branch at arm’s length from trunk or closer. Sometimes we would leave a long low (shaded too much to sprout well or become dominant) branch with unreachable greenery intact, especially if critical for climbing. We generally left about 1/3 the original foliage amount.

White Birch: Goats wanted white birch for a brief mid-springtime window, then for a longer window in fall. They even accepted a completely yellow bit on Oct. 20th, though preferring green leaves of oak. Yet later the yellowed w. birch leaves were accepted by goats and hogs dried, and that same oak dried was rejected by goats and only tasted by hogs.

Most of the Demo Plot white birches had large bare trunks, and high small tops, which we were challenged to access. Slotte (2000) says birches and aspens in Sweden were thinned rather than fully harvested, yet most of ours got pruned heavily due to the height challenge. Three are left for next spring, as the turning of their leaves has gotten ahead of our pruning. I am hoping for arborist training about using spikes (traditional in some European countries, at least on spruces pruned for animal bedding), for one especially tall bare trunk.

We made chop marks every 2 ft. down the bare trunks of the three birches pruned in spring, and are unsure as yet if this will help sprouting. If I succeed in climbing with spikes, the spike wounds may likewise help sprouts emerge from trunk bark.

Only one pollarded white birch (pruned earliest and had young sprouts previous to our pruning) has good new growth; we are hoping the rest will sprout next spring.

Yellow Birch: In later spring we pruned yellow birches, leaving quite a bit of structure and foliage (all now in reach), as they tend to be shaded by other trees in the Demo Plot. Due to their high shade tolerance, they almost always have live branchy climbing structures to begin with. It was never the goats’ favorite fodder, but has a much longer window of acceptance than white birch. We highly enjoyed stripping the aromatic leaves for a silage sample (yet to be fed out); only humans have enjoyed the extremely aromatic chipped dried and ensiled samples.

Half of the Demo Plot yellow birches remain in the shady north corner, to be pruned next spring, as we felt pressed (by goats’ nutritional choices and our own worries about surmounting the taller trees) to start on poplars (aspens) as they became (we thought) sufficiently stocked mid-season.

Big-tooth and Quaking Aspens: We were at first a bit daunted by the height of the bare and sometimes flexible trunks of the aspens. We received well-timed invaluable instruction from Edgar Evenkeel in July, who improved our selection of knots and equipment just as we started on the aspens.

Aspen foliage bunches are mounted upon fragile twigs, often a ways from the trunk. Haakan Slotte wrote that one should thin rather than fully pollard birches and aspens, yet black poplar pollards in England respond well to complete lopping of branches back to a boll or bolls. We left one or two twigs of greenery where possible to reach, and sometimes more on shaded lower limbs which might lack energy to sprout well, but often stubbed to either multiple collars or less often to a bare climbable short length of branch with a single cut in the higher reaches of the tree. Sometimes the twigs we left broke off from subsequent pruning.

We pruned two quaking aspens outside the fence, as they may share roots with our Demo trees, and would likely dominate if left full-sized.

None of the pruned aspens showed any new growth, and remaining leaves partly dried in late summer. We await spring to discover whether we have killed them or not. I have always left almost half of foliage on aspen pollards outside the Demo Plot.

White Ash: We are glad to have a fair number of young ash in the understory, and a handful of mature ashes varying broadly in age. Ash is beloved by all livestock, no matter how we process it. We have pruned most; a couple young ones remain for next summer, and we are debating whether to leave unpruned two slow-growing venerable old seed producers in the pine-shaded north corner.

We often left many shortened branches on the understory ashes, as they are fully accessible already, and may be dominated by the taller pollards of other species if they do not start with some immediate leaves in spring. On higher ashes, we often made only one or two large slightly sloping cuts, leaving stubs or branches mostly having to do with ergonomics of climbing.

Ash pollards outside the Demo Plot have responded well to nearly complete removal of foliage-bearing growth after a 3 year rest, despite ashes’ susceptibility to stress from our droughts 2015 to present. Bolls developing on low side limbs have a harder time maintaining sprouting energy than do bolls near the top (as on most trees); hence our occasional choice to leave a lower limb intact to be sure to retain a live climbing foothold or ladder set.

Red Oak: We pruned all 11 oaks in the Demo Plot, mostly in fall to take advantage of their ability to hold green leaves when other species’ leaves color and drop. They vary broadly in size/age, with most being in early maturity.

Fresh oak was well-received by most livestock, with cattle less enthusiastic than the others. Sheep and some cattle liked dried oak that our goats refused; our goats eagerly ate the dried oak from previously pollarded trees in full sun. The very well-received hand-stripped oak silage was also from these more vibrant pollards.

Some oaks received large top cuts leaving no foliage; some retained a few plumes on shortened branches. One began to sprout in earnest 3 weeks after pruning. The oaks pruned late are likely to wait until spring to sprout. Cuts on oak can stay fungus-free for 7 years or so, while waiting for a healing edge to close; hence our willingness to make some larger cuts.

Red Maple: Most of the large maples were storm pollarded, possibly in the 1998 Ice Storm (our ring counts on maples were visual guesses as rings were quite faint). So I have varied from our originally planned 3 ” cuts, to sometimes re-pollard near an original break, or sometimes cut the old trunk down further, to strong lower growth response to the storm damage. In summer we were leaving “sap risers” (small branches with a bit of foliage) on almost each limb cut back; in winter, I am often leaving only chunky collars or short stubs (probability of sprouting is high on maples).

Smaller diameter maples, responses to basal firewood cuts of the previous landowner pre-2000, were/are often as tall as the larger maples, yet due to smooth young bark we can expect sprouting from a trunk cut in easy reach. These long young tops offer a lot of tasty bark for goats to strip, yet can be deceivingly dangerous to cut. The goats have learned well the command “Watch Out!”

Processing Fodders:

Drying Piles: We found that with a person atop a drying pile holding the leafy ends of a bundle together just past the center of the pile, the person handing up the bundle could spread the larger stick ends for an even horizontally packed tight stack. We found that the center poles were unnecessary, as pile height was limited by our ability to lift the brush, and to mount the pile to spread it. The density of the 5 ft. high piles increased as armloads were added. We worried that leaves would shatter, but air moisture kept them pliable. Mold and insect damage occurred where leaves were concentrated at the center, exacerbated by moisture entering at the pole opening.

Nick Jackson at Jackson Regenerational Farm (one of our sampling farms) misunderstood my verbal description, and did something possibly better: He stacked up to 8 ft. coppice cuttings vertically, stick ends down, wrapping a rope around the initial bundles with a rooted center pole for stability. This configuration may be better for on-site feeding, as animals can eat directly from each layer without temptation to climb and soil the pile.

Chipped quaking aspen silage before and after initial sorting by goats (the kids especially continued to nibble).

Chipping: We chipped into a moveable calf hutch, with cardboard or plywood beneath. The silages packed with a complete inner plastic bag were mold-free; those relying upon just the bucket seal, or just topped with a shopping bag of same fodder, sometimes molded. The molded silages were generally still accepted by livestock.

Kanga sampling dried chipped fodders

Kanga sampling dried chipped fodders

The dried chipped fodders were spread 2″ deep in wooden blueberry flats; aspens tended to mold, and generally the ensiled chips were better received than the dried.

Hand stripping: Ash, aspens and willow were quick to hand-strip, snapping short twigs with leaf bunches. Other species were impractical to hand-strip for silage, yet certainly ranked a notch higher than chipped silages by the animals.

Initial Proposal Outline of Methods (updated):

Study pollards established 2011-‘17 (big toothed aspen, quaking aspen, basswood, beech, black locust, American elm, red maples, red oak, white birch, yellow birch).

Observe productive forms:

March 2018: Contract Intern.

March – April 2018: Tag with species initial, number (surveyor tape, marker) 1 – 4 successful sprouting locations/tree species. Note prior pruning dates (pollard notebook, observe annual growth segments).

May – Sept. 2018: In correct harvest season/species, photograph whole tree and close-up of marked location; prune whole tree; re-photograph (digital camera).

August – Sept. 2019: Re-photograph, 1 yr. growth.

Document healing and structural concerns

March – April 2018: Identify cut diameters/locations with sound closure/species to inform development of durable structures. Photo-illustrate observations.

Summarize and apply: April or Dec, 2018: Draft observation narrative/species with photos;

May – Sept. 2018: Apply observations to:

Demonstration plot: **Because we are measuring person-hours as unknown outcome, demo will be priority of work schedule (above A.) for each species harvest until complete. If under-scheduled, Shana can complete last bits during regular farm pruning time, same months 2019.

Create Demonstration Plot:

March 2018: Mark and April – May 2018: fence (6 strands electric wire) 1 acre square (208’ 8.5” sides) plot of 55 yr. multi-aged species diverse tree growth selectively cut for firewood since 1963; move scale and chipper/shredder, string tarp over.

March – April: Fell most softwoods (retain white cedar, hemlock).

April – May 2018: Draft our “pruning rules” using A.3. (Ongoing – can add and edit – working doc).

Growing season 2018: Prune (hand and power saws, ladders, ropes, harnesses), prioritizing oak, ash, yellow birch and poplars (longer nutritional seasons) over beech, maple, and white birch. Process fodder.

May – June 2018: beech; June and October: white birch; July – Color change: yellow birch, ash, red maple, poplars, red oak.

Spacing >6’ between retained branch structures of separate trees.

Light >1/3 day = 60 degrees of sky (Slotte, 2000), eyed from pruning cut locations

Describe:

March or April 2018: Set up Excel spreadsheets for: tree measurements; livestock weights; livestock responses to offerings.

May – October 2018: Record retained tree species, diameters at 4’ (diameter tape), initial and pruned heights (surveying tape down from top of pruned tree plus length cut central leader), diameter and # growth rings of cut on central leader. Tag and Photograph representative pruned trees.

Nov. – Dec. 2018: Summarize: Compute mean measurements/species (Excel spreadsheet, then chart summary data for Annual Report).

Sept. 2019, SH: Re-photograph tagged trees for Final Report.

Quantify initial plot productivity: Weigh tree matter consumed in goats on demo plot.

May – Oct. 2018: Bring goats each site work day. Record goat weights and time at our entry and exit (platform scales, notebook then Excel on Microsoft Surface Pro 2).

May 2018: During 2 hr. period of goats in enclosure, count defecations and urinations/hrs. Collect and weigh fresh defecation total (bucket, plastic glove). Capture and weigh 3 urinations. Compute rough goat “weight excretions/hour”.

Nov. - Dec. 2018: Compute total weight fresh fodder consumed = (total goat exit weights + weight excretions/hr. x hrs. spent) – total goat entry weights. Compute mean weight fresh tree matter consumed per hr. (Excel).

Dec. 2018 – March 2019: Put goats in demo 2 – 6 hrs./day, 3-4 days/wk. (Water provided in home quarters.) Feed dried branches from storage piles by propping on brush piles, butt ends down. Continue to prune remaining r. maples and softwoods. Weigh goats and compute as b. and d. above, for total weight and mean weight/visit winter fodder consumed.

Nov. - Dec. 2018: Convert lbs. fresh fodder consumed to lbs. Dry Matter (DM), using 40% for growing season, 80% for winter dried leaf/fresh bark and needles mix, and 65% for winter feeds once leaf piles run out DM conversion, to offer an approximate total of lbs. DM edible portion/acre to farmers.

Store: Dry, intact:

May – Oct. 2018: Set 10’ D junk wood bases for branch piles, around standing trimmed center poles cut at 8 ft. (can be rooted).

May – Oct. 2018: Piece unbrowsed branches to < 2 “ butts, length < 8 ft. (wheeler saws, billhooks, loppers) when surplus is evident. Stack, leaf ends inward with 1 –3 ft. overlaps past center pole, such that subsequent layers slope downward toward butts at circumference. Cover with 10’x12’ tarp.

Dry, shredded: May – Oct. 2018:

Shred (Troybilt Super Tomahawk or comparable) twig ends of fresh branches down to 1”, of each species as sufficient quantities are harvested, into 30 gal. barrel to make 20 – 30 loose gal./species.

Spread shredded leafy branches of each species 2” deep in stacked wooden flats, in open barn.

Ensiled:

May – Oct. 2018: Snap off green leaf bunches; fill firmly to 5 gallons (less per species availability) in contractor bag inside 5 gal. bucket, for each broadleaf species in quantity at demo sites, inc. beech, white and yellow birch, white ash, red oak, big tooth, quaking aspen, red maple; compress with hands; tie tightly. Store in cellar.

May – Oct. 2018: Pack shredded branches as above.

Cooked: Jan. 2019: Add water to cover dried leaves of each species. Bring to a simmer. Take off heat and cool slowly. Useful to farms having many sheep and/or goats with small number cows and/or hogs.

Rank livestock fodder responses: May 2018 – March 2019: Trip to all farms for each or multiple feed item/s. (Excel spreadsheet:) Enter date, tree species and description; rank as 3=“immediately consumed”, 2=“eventually consumed”, 1=“nibbled”, or 0=“refused,” by

Freisan-Dorset cross dairy sheep, Y Knot Farm

Icelandic Sheep, Meadowsweet Farm (Nov. 2018 on)

Saanen goats, 3 Streams Farm

American Guinea hogs, 3 Streams Farm

Holstein cows, Faithful Venture Farm

Dexter cow and Dexter-Jersey heifer, Jackson Regenerational Farm (thru Oct. 2018)

Black Angus (mostly) beef cattle, Meadowsweet Farm (Nov. 2018 on)

Organize rankings per livestock species and per tree species.

Time labor output: May – Oct. 2018: Manual labor time on demo site recorded daily. Time collecting data and packing silages not counted. Report total person-hrs. logged.

PLEASE SEE FULL REPORT WITH UPDATED TREE SPECIES PHOTOS AND SUMMARY ATTACHED OR AT

https://3streamsfarmbelfastme.blogspot.com

Initial data in first 1-2 years of study:

We completed initial pollarding (drastic pruning to be repeated cyclically) of about one half of trees in our 1 acre woodland ‘air meadow’ Demo Plot this growing season, with mostly red maples left (goats prefer these in winter). Interns Joshua Kauppila and Emily MacGibeny have both completed their seasons’ commitments and are far away. I have hired new intern Maddy Cain who will join me in April 2019.

I am now pruning red maples and softwoods (we retained firs and pines with live branches <10 ft. up plus hemlock and w. cedar) which goats prefer in winter, and just fed out the last dried leafy branches from 3 storage piles there (excepting samples saved for our next trip to other farms, and a pile of green but goat-rejected oak to chip, re-moisten and ensile). Entries on spread sheets for goat weights (from which to compute dry matter consumed) and tree measurements (to describe our plot) therefore continue.

Person-hours: We spent 454 person-hrs. felling tightly spaced softwoods and re-structuring the 5/8 acre’s worth of trees completed to 12/25/18 and dealing with brush /fodder. So we are taking about 726 person-hours/acre. Hiring an arborist would have been less expensive and much quicker, yet the goats could not have eaten as much fresh if pruning had happened all at once. Our time working in company of goats has been pleasant, often above the biting insect zone with partial shade for summer heat, and much stretching in varied use of our bodies. (Josh pictured below.)

DM edible portion: The goats ate about 500 lbs. of fresh tree leaves (about 200 lbs. DM) from the 1/2 of trees in our 1 acre Demo Plot which we struggled to prune fast enough for them during the growing season. Goats ate about 1/3 fresh lb. per hr. per adult doe. Nov. 1st to Dec. 25th they have eaten about 286 lbs. dried leaves and fresh bark combined (bark being from an additional 1/8 of Demo Plot trees), eating a bit more than 1/3 lb. dried leaves and fresh bark per adult goat per hr., (filling bellies much more thoroughly with these immediately abundant and drier feeds). This gives us a DM total of about 687 lbs. DM/acre being consumed by goats during initial restructuring of ‘air meadow’ trees. We are now out of dried leaves; yet I expect our DM consumed/acre figure to continue to rise as I prune the remaining 3/8 of Demo Plot trees, due to the higher rate of winter eating of choice red maple bark versus summer eating of sometimes non-choice fresh leaf species, the more easily climbable structures of maple trees, and slower perishability of prunings in winter.

Limiting factors during the growing season were: our ineptness at use of throw ball for getting ropes up into crowded trees with small high tops giving small returns per tree (particularly the aspens and white birches); same denseness making softwoods complicated to fell (easier once broadleaf trees were pollarded, but goats do not utilize softwoods well in summer, and we thought it important for sun to get in right at the beginning); a preponderance of red maple and softwoods which goats do not prefer in summer; and our research need to dry and to ensile portions of all species, some of which goats wanted fresh or ensiled, but have refused dried (particularly quaking and big toothed aspens cut before frost, and red oak).

The sheep and cows of other farms plus our own hogs all eagerly ate certain offerings rejected by our goats. Therefore if we had added a small cow and some sheep to the herd (the hogs would have done damage to ground layer plants and dried already too dry soil) versus just goats visiting the Demo Plot, fodder utilization may have been as much as 1/3 greater and “waste” (tree mulch) lower. Such mixed-species browsing could lead to a higher DM edible portion figure per woodland acre.

Also our simple research plan prevented the offering of grassland or hay simultaneous to livestock time accessing the tree leaf fodder. It is known that even goats, who are more able than other livestock to deal with high tannin levels in tree matter, can eat more tree matter in a mixed diet with grass and herbs, yet this would have complicated our measurement methods. Meadowsweet Farm cows last summer demonstrated this point to their farmers, who in response to drought conditions at first offered them paddocks of woodland with felled trees, but found the addition of a half-ration patch of pasture near the woods enabled the cattle to eat the tree leaves.

With a mixed herd, and mixed tree leaf and grass fodder, one would achieve a more optimum tree fodder DM/acre figure.

Storage: On-site feeding from the Demo Plot piles has been labor-saving and of significant feed value despite some insect damage, molds, and rejected tree species. One dried leaf storage pile’s center raised small green caterpillars making lace and excrement of aspen and oak leaves especially (ash seemed immune; r. maple and birches barely touched). Another pile molded on top in the center, helped by small gaps in tarping around the original pole (later cut short). About 2/3 leaves in the 3 storage piles retained green color and intact quality. Yet one doe one day was selecting molded aspen leaves over dried green aspen leaves (fresh aspen leaves from young root-sprouts and dried aspen leaves seem to have an anti-feedant issue for goats unless cut after frost). Barn dried leafy branches were insect free, but generally less colorful than those (shown below) from the densely packed tarped piles.

Livestock preferred courser shredding or chipping to fine, and picked through for largest leaf pieces, whether ensiled or dried (remaining woody chips contribute positively to bedding materials). I hope to perfect the speed of chipping or shredding in 2019 to produce the leafiest least ground-up texture.

Chipped fodders ensiled in buckets and barrels produced more consistent quality (less mold, more green, and very well-received by all livestock) than those spread in wooden boxes in an open barn to dry. Humans consistently enjoyed the aromas of our leaf silages. Animals generally preferred even the three molded silages over dried leaves. Regardless, some species of even dried chipped leafy branches were popular with all livestock.

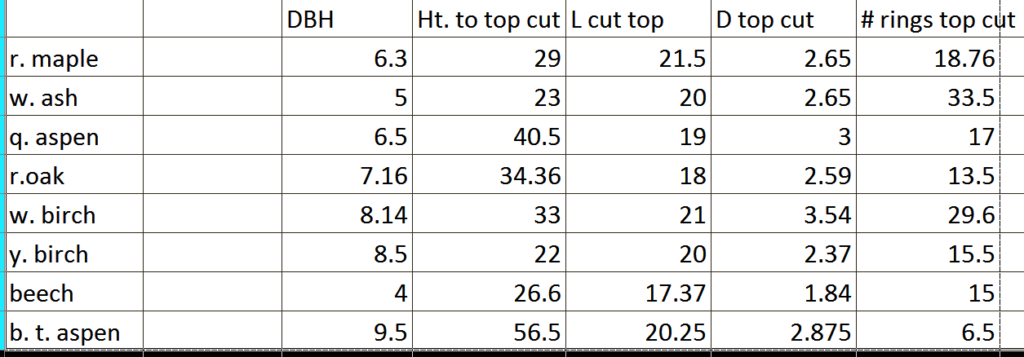

Initial restructuring (pollarding); Broadleaf Tree descriptive data:

Mean measurements on newly pollarded broadleaf trees:

(Height at Top Cut of maples will be decreasing with winter trunk cuts on young previously coppiced maples)

See www.3streamsfarmbelfastme.blogspot.com “Tree Inventory” spreadsheet with above stats per tree plus date cut, moon phase etc. Scroll to the bottom to see species separated and summarized, and then new winter data beginning.

Softwoods: We retained the few hemlocks and white cedars to prune, plus all firs and pines with live branches below 10 ft. were topped rather than felled. Two grand white pines are also remaining unaltered.

Tally of felled softwoods:

DBH = Diameter at Breast Height (we measure inches to the nearest 1/8 with a tree diameter tape at about 4 ft. from the ground).

Height to top cut = feet from the ground to the highest pruning cut we made on the tree.

L cut top = length (feet) of the tallest or most dominant piece of the tree that we cut off, usually cut from the "top cut."

(L cut top + H to top cut = original height of the tree before initial pollarding or pruning.)

D top cut = diameter (inches to nearest 1/8) of the highest pruning cut we made (usually same as the butt of the "cut top").

# rings top cut = tree rings (representing years of growth or age at which the tree reached the height of this top pruning cut) counted visually (with LOTS of room for error, especially on red maples).

Tree sprouting responses: Red maples (below ctr.), some oaks (below R), and one white birch (below L) have responded to initial pollarding with significant sprouts. I expect most others to begin to sprout in spring, but am not counting upon the aspens, as their leaves we retained were drying toward the end of our summer drought.

See www.3streamsfarmbelfastme.blogspot.com for picture files of both newly pollarded trees in the Demo Plot and established pollards elsewhere on the farm that we are re-pruning and watching/photographing. I will take pictures of sprouting of tagged tree joints in September 2019 as written; there will be up to 2 seasons’ growth on some of the trees, as maples for instance were pruned last winter (original write-up said 1 yr’s. growth, which will be true for a few trees)

Photos of healing on previously established pollards are also there, and will be discussed in our 2020 Final Report “Pruning Guidelines” section.

Livestock responses: Livestock sampling of fresh intact and fresh chipped leafy branches was generally very positive, with almost 4/5 of offerings eaten immediately or eventually. Holstein cows at Faithful Venture Farm were least enthusiastic, with widely varying responses probably related to the timing of visits. Unfortunately they were the farthest away and my own time window tended to be evening when they were receiving other feed in the barn. Also a small wide free goat was confounding reliability of any “2 eventually ate” entries. I may make return visits to the Holsteins with fresh fodders in 2019, to correct these issues.

I am now taking data on livestock responses to ensiled chipped and ensiled hand-stripped leafy branches, plus to dried intact and dried chipped leafy branches. As Jackson Regenerational Farm no longer has cattle, Meadowsweet Farm sheep and cows are now on board, with extremely positive responses to 10 silages and 13 dried samples at first visit on 11/21/18 (photos below).

Ensiled leaves have been positively received by all our livestock samplers, and are generally preferred over dried leaves, with intact preferred over chipped, whether dry or ensiled. Ash and willow are devoured in any form by all livestock. Goats eagerly eat chipped ensiled aspen though they are refusing even intact aspen dried unless cut after frost and turning. Cattle and hogs (and occasionally sheep or goats though less traditional) have begun to sample traditionally cooked dried leaves of various species, with positive responses especially from the cattle - even Faithful Venture Holsteins! who so far rank cooked leaves even above ensiled leaves.

R.I.P Alchemy, the bull-calf raised primarily on tree leaves at Jackson Regenerational Farm, who was an especially sweet-tempered and appreciative contact. His hanging weight was 150 lbs. after one summer of life.

Animal Response Summary Chart: these response means do not reflect range of responses.

See “Animal Responses” spreadsheet at www.3streamsfarmbelfastme.blogspot.com for full range of responses.

PLEASE SEE FULL REPORT WITH UPDATED TREE SPECIES PHOTOS AND SUMMARY ATTACHED OR AT

https://3streamsfarmbelfastme.blogspot.com

FOR FINAL TABLES AND PHOTOS.

Final discussion of all collected data:

We sought to restructure one acre of woodland into fodder-producing pollarded “air meadow” in one growing season, and have found that (due to our amateur climbing skills) we need the remaining time in our grant period to complete this Demo Plot. Fodder returns have been low at 1 lb. Dry Matter/person-hr. worked. Yet in subsequent harvests we expect prunings to be more leafy with less wood, and to average something like 3 to 6 ft. long instead of these initial rather dangerous 15 to 40 ft. tops we have been dropping. Some hard-to-reach tree tops may shift their energy downward, if weather does not allow them to sprout sufficient leafy surface to draw sap so disproportionately far, and we expect sunlight to help trees develop new low branches that will make climbing entry easier. Over time the bush and ground layers should offer livestock more browse as they wait for prunings to drop.

Pollarding guidelines with species-specific comments are offered in an attached report, recommending ideally 3" diameter cuts in wood in young wood no more than an arm’s reach from the trunk, and prioritizing trees that start with good health, low branches and full canopies, for economy of form that supports sap flow reaching sprout locations.

We succeeded in obtaining cattle, sheep, goat and hog responses to a broad range of tree leaf fodder products, with predominantly positive responses to fresh, dried, ensiled, and cooked leaves or leafy branches. We are especially excited about the logistically easier chipped or shredded silages. Cattle, sheep, goats, and hogs at 6 farms sampled fresh leafy branches both intact and chipped, and above forms of stored fodders of 15 tree species, plus cooked dried leaves of 8 species, with more than two thirds of offered samples accepted: 52% of 740 samplings rated by observation as “immediately consumed” and another 19% rated as “eventually consumed,” versus 12% “tasted” and 17% “refused.”

We have extensive photographic data on trees being pollarded, and next fall will add pictures of new growth, from which to draw species-specific conclusions about our pruning protocols. In addition to requirements of our grant, we added moon phase information to our tree inventory, and hope to learn more from both our tree sprouting responses and from European University contacts about timing cutting in relation to moon-weeks.

Winter storage methods of on-site stacking, chipping and drying, and container-ensiling both chipped leafy branches and hand-stripped leaves (usually leaf bunches with basal twigs), were trialed with about 20% mold or caterpillar damage observed (at leafy center tarp openings) in on-site horizontal stacks but 0% damage in Jackson Regenerational Farm’s vertical stacks, 0% mold in chipped dried species other than aspens but about 90% mold observed in chipped dried aspens, and about 3% (seemingly edible) mold observed at air leaks in silages.

In final analysis, we timed our labor to be 604 person-hrs./acre, which included tight intricate felling of most firs before starting the pruning of canopies, very slow setting of climbing ropes by us amateurs, and piecing and stacking of brush throughout.

We found that 1,216 lbs. dry matter (DM) per acre were eaten by selective goats and estimate that 1500 lbs DM is closer to the truth based on other intake data measured on cooperating farms from cattle and sheep. Subsequent harvests of 4 to 6 yr. old sprout-wood will be more palatable than these initial 20 yr. old tops, according to 3 Streams Farm goats and established pollards. We expect 92% of demo plot trees to become productive healthy fodder trees on existing trunks.

We look forward to continuing to utilize and monitor the progress and fodder offerings of the “air meadow” Demo Plot trees along with our goats and hogs, to the end of this grant period, and in years to come.

Our Northeastern tree leaves were readily eaten fresh, dried, and ensiled by cattle, sheep, goats, and hogs, and have potential to increase farm feed security. Chipped feeds fresh, dried, and ensiled of most species were accepted, and would take less storage space if a leaf-separating rake preceded, or in-line fan followed (idea thanks to Aidan Clowes, Westminster, Vt.), the chipper intake to keep wood chip (bedding) and feed portions separate. On-site tight stacking of <8’ fresh leafy branches to dry under tarps worked, with some loss of quality where leafiest branch tips overlapped in pile centers (we had butts outward to avoid theft by goats); such quality loss was avoided in Jackson Regenerational Farm’s vertical butt-down stacking.

Pollarding a woodland above browse height allowed livestock access without tree sprout damage, and the increased light, droppings and trampling stimulated unexpected grazable ground layer greenery. 30 year old or younger woodland growth should be tried with power tools or even feller-buncher, as our 55 yr. old growth with mostly hand saws was too time-intensive at initial restructuring to be viable for most farmers. Labor of subsequent harvest cycles is likely to be more economical, though still more time consuming than harvest of a hay field (but also cooler and very fun I think).

Fodder yield/acre of this 55 year mixed-age woodland from initial re-structuring was about one half the average 2018 Maine hay yield, and a transition to hay there would not be advisable due to the flood zone and uneven ground. The next harvest, in 4 to 6 years, we expect will have higher palatability and % edible portion (as yet unmeasured for the Northeast; Brauner, 1756 in Sweden wrote “as good as a good hay meadow”).

Labor and yield differences in using these mineral- and plant compound-rich feeds may be possible to offset through study of health benefits to humans who eat the food products raised, and pricing that reflects this quality difference.

Environmental benefits of food production from woodland may at some point trump all economic concerns, or receive policy-related payment rewards, if climate patterns and ecological systems continue to deteriorate worldwide.

Environmental benefits to livestock on-farm may also raise the value of an “air meadow” woodland strategy, which can buffer temperature extremes while allowing enough light for new pasture growth under the pollards. The cyclical canopy harvest of “air meadow” maintains steadier ground light over time than do silvopastural models that rely on cycles of felling, and makes the difficulty of successional tree plantings among livestock unnecessary.

Northeastern farmers can beneficially work on areas of “air meadow” tree canopy harvest in woodland, or use easy-access trees in or along edges of pastures (that start with broad canopies and low branches) at times when feed shortages raise feed value and decrease feed source choices, or at points in the year when time allows, in preparation for such need.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

For Colloque Trognes in Sare, France March 2nd I spoke about “Tasty timing of leaf harvests,” based upon literature resources and my observations of goats and hogs, and produced an article and PowerPoint on same. I announced this SARE grant in my presentation, but the coinciding name of the town we were in may have confused listeners.

I have presented about our study at 9 outreach events in 4 states, reaching about 160 participants, and now have a contact list of people who want to know more about using tree leaf fodders. Updates on progress were offered at both 2018 and 2019 MOFGA Tree Fodder Days, and attendees of the 2018 and 2019 Tree Fodder Seminars spent time learning various skills in the Demo Plot. Shana led people in pollarding willows at the 2018 MOFGA Farm and Homestead Day, and helped them make and use climbing harnesses in 2019. She presented “Tree Leaf Preferences of Cattle, Sheep, Goats and Hogs” at both the 2018 and 2019 Common Ground Fairs. At MOFGA Farm and Homestead Day in June,I helped children climb ladders to feed goats from a tall row of hybrid willows, and conversed with all ages about our SARE project. MOFGA Tree Fodder Day July 9 was a resounding success; I verbally summarized our SARE project during the farm presentations, then passed around silage and chipped dried samples during our storage discussion circle. In the remaining days of the Tree Fodder Seminar, arborist climbing instruction and mushroom inoculation workshops occurred on farm in our SARE Demo Plot, where initial pruning was well under way.

Shana made it to NOFA MA Winter Conference (powerpoint at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1P4NHKslaS5FHt_FT94ZlnltmcMoBrOw_ ) to present “Tree Leaf Fodder for Livestock and Climate Resilience.” and to NOFA NH 2019 Winter Conference (powerpoint at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rsFQ48y_iG4Mz-FQ6ccUNkP2xUDKY3ON/view) .

MOFGA Farmer to Farmer Conference requested a broader presentation topic (see videos at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ku0aIUS_rts and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ex05wSQSDp8&t=28s, plus powerpoint at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1JEnMgruxOgo7Ca4qiSBn02QviCIqGLb7/view).

Shana tabled with her extensive collection of literature about tree leaf fodder at Vermont Grazing and Livestock Conference January 17-18, 2020, answering questions, learning from others, offering a “poster presentation” of results of the VGFA Mini-grant which has paid for lab testing of samples created by this SARE project, and offering materials from this SARE Final Report.

The final full report is attached and found on my website https://3streamsfarmbelfastme.blogspot.com

Learning Outcomes

- Learning from Observation of Existing Pollards

I used to advise that healing edges should close over initial pollarding cuts before the next harvest; this would be ideal, except that I saw one sprout often becoming dominant to replace the branch over time, versus developing sprouting heads or bolls, and very few cuts closed completely even when cut 9 years ago. So I have tended to prune sooner to train the trees toward more prolific and accessible sprouting.

Maples and birches had soft fungal wood in almost all exposed cuts by year 3, yet growth was strong and healing edges healthy. So I have been letting go of my concerns about healing and fungus, and gaining trust in the trees’ ability to thrive. Ancient pollards still alive in Europe are riddled with fungus and hollows, supporting incredible biodiversity. It does remain important to observe and assess where one places one’s weight when climbing, and large diameter trunk cuts are still not recommended.

Growth on previously pollarded large maples on-farm has been more vigorous than what we are seeing in the Demo Plot. This difference does not seem solely due to starting with broader healthier canopies, nor does it seem that even the 4th consecutive summer of drought would cause such difficulty in a flood zone. I guess the learning is about mystery, and gratitude for the miracle when trees sprout well.

- Learning from Demonstration Plot

We had no idea how much work we’d committed to! We did learn to climb. I would advise writing such a proposal as working a set number of days, THEN measuring the area completed. Yet the area now is a joy to visit, and I look forward to observing it as the goats and cow browse, as we pollard adjacent areas (which I have begun).

As stated under “Labor” above, Demo Plot poplars and some of the less vigorous red maples are struggling to maintain life in their disproportionately high pollarded crowns. Felling such trees would have saved time, while still providing tops to goats and poplar root sprouts to pollard later (maple root sprouts do not survive the presence of goats).

There were also a few unexpected failures to sprout among small understory firewood-coppiced maples, on the drier east side of the Demo Plot.

Our 2.88 “ average diameter top cuts averaged about 20 years old, older than I expected. Clearly growth had slowed in this closing canopy, and we would have done well to start this area 20 years ago.

- Learning from Storage Methods

I already knew that drying leafy branches is much easier and less weather-dependent than making grass hay, but was impressed at the bright color retention and good condition of most of the leaves in our piles, especially considering the non-traditional long length we chose (my sense has always been that goodness from the leaves recedes back into the wood, to try to stay alive as they dry). My impression is that traditional sheaves were quite standardized at about 1 meter long.

The chipper blew our first shredded beech fodder right through a previously intact tarp; the spare calf hutch provided a better catchment system. We chipped most too finely to be ideal for sheep and goats, and should have continued to shred more and chip less, perhaps varying speed to find the best texture. Ensiling was surprisingly easy and fool-proof, and shelf life was longer than expected; goats and heiffer enjoyed some left-overs in mid-summer. Drying chips took way too much space and care (I think Austad et al used a fodder drying machine).

- Learning from Livestock Responses

Sampling by livestock caused me to organize a lot of information to share with others. I already knew a lot about browse, from 15 years with goats, and from endlessly collecting browse literature. I’d even brought elm silage to Glendon’s Holsteins the year before. Yet there were points of learning for me too.

Meadowsweet Farm and I were amazed at the appetites of their beef cattle and sheep for almost all our offerings, including chipped fodders. At North Branch Farm, one heifer wanted way more than the others (she ate everything we brought), so she moved to my farm – my first cow, for ongoing learning and draft power. Once there, she sought out woodland duff and rotten stumps to eat, as do all my baby goats – but she was 2 yrs. old. She also wanted to taste all conk fungi and strip moss off rocks, all fringe benefits from the “air meadow” for the rumen. I was surprised that our drab traditional dried leaves cooked in water were as popular with the Holsteins as were bright aromatic ensiled leaves. But the ensiled leaves were more convenient. The hogs strangely did not want basswood, despite having similar digestive systems to ours, and wanted mature beech leaves in summer. They pointed me to the beech tree – I would not have otherwise cut beech then, based on many years with goats.

- Learning from writing Pollarding Guidelines

This task was humbling; I had to face how organic and fluid my process is with trees, and how little I can assure someone of results, especially without seeing their trees. I pray that my attempt is more helpful than confusing. I continue to seek instruction from all others who pollard.

Project Outcomes

I am now involved in the Northeast Mid-Atlantic Agroforestry working group consisting of about 50 members that meets quarterly by conferencing call/video.

I have been speaking with fabricators about what a leaf rake attachment would look like, to precede the intake hopper of Meadowsweet Farm’s PTO driven chipper, such that leaves and chipped wood would land in separate containers. This would improve palatability and save silo (container) space, while still producing bedding material as a byproduct.

A three-sided silage bunker with tarp well-weighted and tucked in edges would avoid cost of containers and use less plastic. Alternatively, sections of 4 ft. diameter silage tube might be tried on pallets with bottom ends folded under, and top folded and taped, for movable tractor-scale leaf silage. I wrote a grant pre-proposal to support trying this and other ideas to scale up, but must continue to apply.

I have begun a conversation about mechanical pollarding with Graham at the Great Farm in Jackson, ME, who is using his feller-buncher to thin trees for silvopasture. I have located a log arch for my cow-ox to use to move pine logs here, if she becomes handy enough, to let sun into more pollardable trees.

Meanwhile, I continue to climb, but now with determination to complete enough “air meadow” for a 5 year rotation. I am more assertively felling trees who are unlikely pollard candidates, and am currently focused on the bit of my land blessed with white and brown ash near the front stream, for happy goats this summer (pruning the red maples there 1st, this winter). This will give the south edge of our Demo Plot much-needed sun.

At Meadowsweet Farm, Eliot is contemplating sapling protectors, to plant more shade and leaf fodder into the pastures. In summer and fall of 2018 he and Reyna extended paddocks into woodland in response to drought, and felled trees for the cattle and sheep. In winter they bale-grazed cattle under trees, to start more pasture there. In both 2018 and -19 they stored dried leafy branches in their capacious barn.

I called and talked to 5 people who attended my various presentations and did not provide emails. 4 of them are feeding more tree matter than before, 2 are beginning to pollard ash, one is planning a sod bunker to hold hand-snapped silage, and wonders if the probiotics of leaf silage can increase digestive efficiency of sheep, to decrease winter hay rations (I recommended that he apply for a SARE grant).

I likewise called Judy Holland at Ravenwood, Searsmont, ME, who replied by email: “After learning from Shana Hanson a bit about leaf fodder I have experimented with feeding leaves to my sheep. I have watched the sheep self select during the summer season and supplement their limited pasture with branches. I now have a leaf shredder and can make silage or shredded leaves for winter consumption. Still a work in progress as time and energy permit.”

A contact from our 2019 Tree Fodder Seminar has created an email list, from my paper notes of 150 tree fodder presentation contacts (plus now 18 more to add), and has sent a link to our website with this report, with a request to hear what folks are doing. It seems that face-to-face and phone contact get more response, but these folks may contact me as they start making changes toward using their tree resources.

I have been freezing small samples of each silage opened, and in my process of scrambling to explore grant funding the nutritional testing of these samples, my University contacts doubled and became newly aware of our SARE project. In visiting farms for livestock responses plus playing fiddle at Camden Farmers’ Market, I connected with two more arborists, one of whom is now on board to bring us large amounts of ensilable chipped leafy branches of various species, taking us perhaps toward an “Innovative Practices” exploration of using Faithful Venture Farm’s bail wrapper to ensile in one-ton tote bags.