Final report for FNE18-915

Project Information

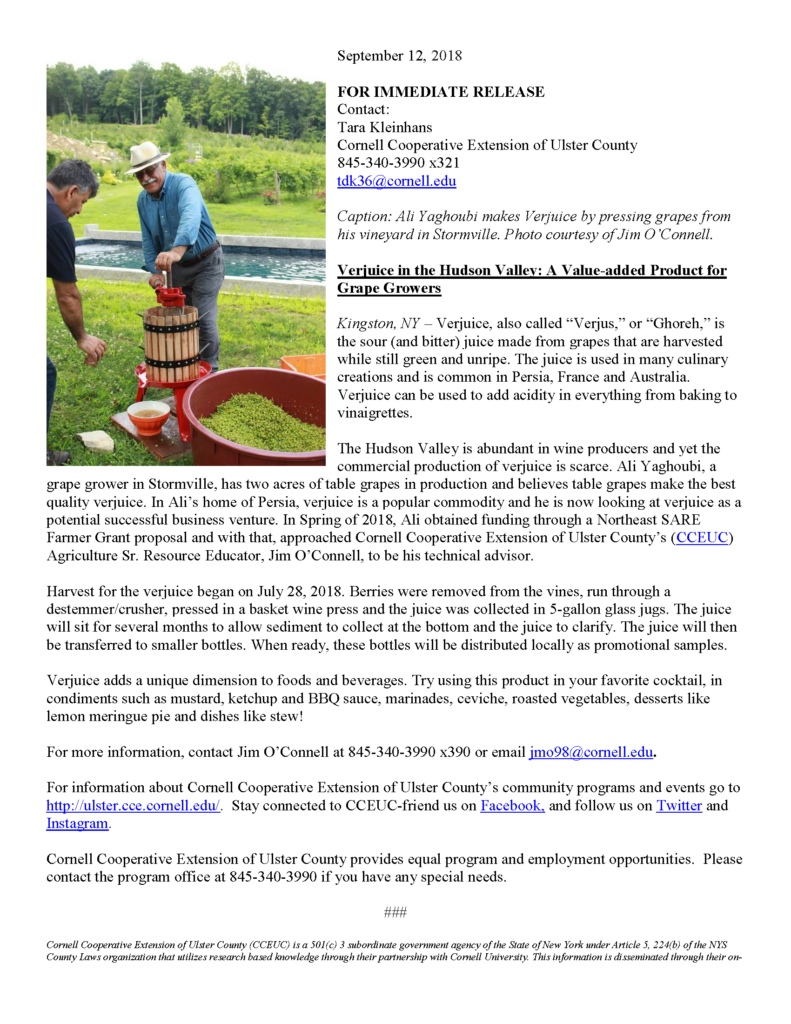

I wanted to know if I could make verjuice, a juice pressed from unripe grapes, in the Hudson Valley. In my home country of Persia, it's commonly used in anything we cook. I used 1/8 of my existing table grape vineyard (Einset cultivar) to produce verjuice. Standard practices of pruning, shoot thinning, and pest management were used up to harvest. IPM practices were adjusted for the earlier harvest to comply with pesticide residues. The grapes were picked before sugar developed, passed through a crusher/destemmer twice, and then pressed in a basket press to extract the juice. This juice was then bottled into multiple 1 gallon glass bottles and allowed to rest for 45 days. After 45 days, the sediment had settled, and the verjuice was racked into clean/sterile bottles.

2017 numbers were used for table grape production since it was a more "normal" production year. It cost $607.00 to produce 1/8 acre of table grapes in 2017. Total sales for 1/8 acre totaled approximately $700.00, for a profit of $93.00. It cost $332.00 to produce 1/8 acre of verjuice (see tables below for complete breakdown of costs). It’s estimate that verjuice can sell for $13/bottle with a potential revenue of between $351.00 (30% sales or 54 bottles at $13.00 each) and $1,053 (90% sales or 162 bottles at $13 each). That would be an estimated profit of between $20.00 and $722.00 for 1/8 of an acre.

Overall, I proved that I could make verjuice in the Hudson Valley that was similar what I remember from my home in Persia. I still need to work on the labeling process and quality testing with the Food Venture Lab at Cornell before I can sell verjuice.

As my technical advisor, Jim O'Connell did a lot of outreach through newsletters, social media and press releases. These reached anyone who subscribed, from farmers and the general public to magazine editors and other news outlets. I connected with a Persian chef in Brooklyn, NY as well as the Culinary Institute in Hyde Park, NY to promote and use my product.

1/8 acre of my existing vineyard was used for this project. Grape vines were pruned, fertilized, and shoots thinned the same for the whole vineyard (i.e. standard production practices for grape production). Normal IPM practices were used to manage pests. However, materials used and timing of applications were adjusted to have the appropriate days to harvest for the crop. No control was used since this was not an experiment with varying treatments.

Objectives

- Compared production costs of verjuice with table grapes. 2017 was used as the production year since it was a more “normal” production year. 2018 was a wet year and growers across the state had lower yields. As a grower, I knew my cost of production and return on investment for table grapes. However, production costs for Verjuice grapes were more less known since they are harvested earlier. Therefore, it was important to compare costs and revenues for the two systems. The same cultivars selected for Verjuice, were compared to the same cultivars designated for table grape sales.

- Compared the yields from each system. Yields helped provide a measure of cost to produce a particular product. For table grapes the overall yield results were in price per pound revenue. For Verjuice, yield was more price of pound of grapes per bottle (similar to wine grapes).

- Total sales were another measurement of this project. Sales help gauge the profitability of this product. Sales for verjuice were estimated. The process (e.g. bottling, lab testing, labeling, etc.) to bring a new product to market was more involved than I thought. Therefore, I estimated verjuice sales and compared them to sales from table grapes in 2017.

New York State is home to over 400 wineries and 39,000 acres of grapes, providing an annual economic benefit of more than $4.8 billion dollars. The Hudson Valley is home to 49 wineries, 235 acres of vineyards and three wine trails.

I own a two-acre vineyard in lower Dutchess County, near Hopewell Junction, NY, where I grow eight different cultivars of table grapes. My vineyard is on a 15% east facing slope of well-drained soil, classified as Hollis-Chatfield-Rock outcrop complex, hilly by Web Soil Survey. When I first bought my property five years ago, I made decision to grow table grapes after researching and finding that in Dutchess County alone, there were several established vineyard wineries within a 30-mile drive of my location. Across the river, in nearby Ulster County, there were several more vineyard wineries within a similar distance. Currently, at least two more vineyard wineries have opened in Dutchess County. Between three and four more have since opened in Ulster County. Wine from these vineyards is found at nearby farm stands and markets.

In this competitive industry, it is necessary to improve productivity and increase net farm income. Growing grapes has been a profitable and enjoyable experience and I sought to expand my operation further. However, increased production of table grapes was not economically sustainable. These grapes are highly perishable and there is limited growth potential in the table grape market. Producing wine was appealing, however, that too was not be economically sustainable. With the large upfront infrastructure investment (e.g. vines and buildings), the years to vine maturity and actual grape production, it was thought that the markets may be saturated with local wines, making for greater than expected competition.

As a result, then, the key to expansion and competition was diversity and venturing into new and untapped markets. As part of my long term strategy to diversify my farm operation, I recently planted various tree fruit cultivars, which take several years before they begin production. Verjuice was a more immediate possibility and was unique enough that the market wasn’t already saturated. This juice is an acidic, slightly sour liquid made from unripe grapes. It is a product I knew and was familiar with producing. In my home country of Persia, it is called, “Ghoreh.”

Verjuice was popular around the world from the Middle Ages onward. It was used in many recipes, including soups and stews, as well as being used as condiment itself. In Persian culture (my heritage), before the availability of store bought Verjuice, families would purchase as much fresh sour grapes as was in their means to then wash and crush into Verjuice. This homemade Verjuice was then stored and used over the winter. Verjuice in general, fell out of popularity in other parts of the world when lemons became more accessible and affordable. It has since seen a modern resurgence. Maggie Beer, an Australian cook and food writer, began commercial production of Verjuice in 1984 and it has steadily gained popularity. Even France, where wine production accounts for 20% of the world’s wine, verjuice is widely used in their cuisine to heighten flavors of soups and sauces. Furthermore, because of its similar acidity to wine, verjuice will not distort the essence of wine and can be used as a salad dressing.

The market in New York State appears to be in its infancy. An article in the 2012 Finger Lakes Times indicated that there were only five producers of Verjuice in the U.S. The article continued with a brief history of Verjuice and discussed its popularity all over the world except the U.S. More recently, in 2015, Niagara Oast House Brewers, in Niagara on the Lake Ontario, developed a Verjuice product made from Pinot Noir grapes. Several other producers in varying regions of Canada including parts of the Niagara Peninsula also produced Verjuice, as well as a vineyard in the Finger Lakes and one on Long Island (both used unripe wine grapes). With increasing global trade and consumers becoming more well-traveled, it was a good time to bring this product to market.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor (Educator)

Research

Pruning the vineyard was the first step of the season. Ali, Jim (CCE Technical Advisor), Alfonso (vineyard worker) and two friends volunteered their time to prune the vineyard in mid-April. Jim worked one on one with me and taught me how to properly prune the vines. He also demonstrated cane pruning to the other pruners, a technique that was new to them. My friends traditionally spur prune, because it is easier. Jim was concerned that repeated spur pruning was reducing fruiting wood and recommended cane pruning to renew the fruiting wood.

Grapes fruit on one-year-old wood and proper pruning helps maintain the vine health, by removing older unproductive wood. Spur pruning is a quick and easy way to prune grapes. All canes are cut to 3-4 nodes in length and spaced four to six inches apart. Over time, however, the spurs become too long, are too far from the fruiting wire and required renewal (replacement). Cane pruning replaces an entire branch on the grape vine and helps to keep the fruiting wood near the trellis. Jim also explained that cane pruning is used more frequently in the northeast because of the low winter temperatures. These low temperatures can injure buds, limiting the amount of available spurs. Cane renewals replace an entire branch and bring with it new fruitful buds.

After pruning, the next management practice was shoot thinning. The same team that pruned the vineyard, returned in early June (at 5-6 inches of growth) and helped shoot thin the vines. Shoot thinning helps balance vegetative and fruitful shoots. It also reduced canopy crowding and improved air circulation. Improved air circulation promoted quicker drying of the leaves and fruit and allowed for better spray penetration, all of which helped reduce disease pressure.

Standard integrated pest management strategies, began after shoot thinning, continued through the summer and concluded prior to harvest. Summer pruning, removing vigorous green shoots, occurred after shoot thinning and throughout the growing season. Similar to shoot thinning, this step helped prevent overcrowding among the branches. It allowed air and sunlight to more easily penetrate the canopy.

Einset table grapes were used for verjuice and were harvested in late summer before veraison started. Verjuice harvested started on July 28, 2018 and ended on August 4, 2018. Grapes were harvested before veraison since sugar development in the grapes would alter the flavor and balance, making a product closer to wine. Grapes were harvested by hand. They were pruned from the vines, placed into baskets and removed from the field.

The first part of making verjuice was similar to making wine. The grapes were pressed to get the juice. Harvested grapes were placed into a crusher/destemmer to remove stems, which prepared them for pressing. For varieties, like Einset, which at harvest were smaller sized grapes, several passes through crusher/destemmer were needed. These grapes also needed additional sorting to remove any stems not caught by the machine, so they could be pressed more easily.

Once passed through the crusher/destemmer, the grapes were transferred to a manual press filled ¾ full with grapes. After the lid was secured to the top, the press was cranked and the juice released. The juice was collected into multiple 1-gallon glass jugs with plastic swing top caps with rubber gaskets (750 ml swing top bottles were used after running out of 1 gallon bottles), where it remained for 45 days in direct sunlight, allowing sediment to fall to the bottom and the verjuice to clarify. After resting, the verjuice was then racked into clean bottles. As an additional measure, the verjuice was passed through cheesecloth to remove any remaining sediment. Plastic bottles were not used in this step since they may alter the taste of the verjuice.

Grapes for verjuice were harvested before veraison to ensure high acid and low sugar levels. Based on previous years’ experience, I harvested grapes for verjuice from July 28, 2018 to August 4, 2018, when grapes were still green and about pea sized. Harvest for verjuice yielded about 0.25 tons of grapes for 1/8 of an acre.

The verjuice remained bottled outside in direct sunlight for 45 days. The average max day temperature was 80F and the average low night temperature was 64F. The bottles were tightly sealed and no rain entered. Conditions in the bottle were anaerobic (little to no sugar, low pH and no oxygen). Some fermentation did occur, however, not enough to produce alcohol. The warm days helped speed up the fermentation process and aided in clarifying the verjuice. After the sediment fell to the bottom of the bottle and the juice clarified, it was racked into clean and sterile bottles.

Grapes for verjuice were harvested earlier than grapes sold to the fresh market. 2018 was a challenging year because of so much rain. As table grape harvest neared, there was more disease pressure in my vineyard, which required extra sprays. Because grapes for verjuice were harvested before veraison, late season disease management was not necessary, and that saved time and money.

It cost $607.00 to produce 1/8 acre of table grapes in 2017. The weather was drier and the quality of the grapes was better. This year, because of the rain, production costs were higher and the quality of grapes was poorer. Therefore, since 2017 was closer to a normal growing year those numbers were used for comparison to verjuice. Total sales for 1/8 acre totaled approximately $700.00, for a profit of $93.00.

It cost $332.00 to produce 1/8 acre of verjuice (see tables below for complete breakdown of costs). It’s estimate that verjuice can sell for $13/bottle with a potential revenue of between $351.00 (30% sales or 54 bottles at $13.00 each) and $1,053 (90% sales or 162 bottles at $13 each). That would be an estimated profit of between $20.00 and $722.00 for 1/8 of an acre.

After harvesting and pressing the grapes for verjuice, I realized I would not be able to sell verjuice this year. There are a lot steps and procedures to follow before selling this product, especially since the way it is made in Persia may not be an acceptable practice in this country. In Persia, after the juice is bottled, it is left outside in the sun to develop into verjuice. Historically, in my home country, verjuice was always made this way and there have been no health problems with it. Jim O'Connell advised me that with updates to food safety laws, this method may not be an acceptable practice here. I have since contacted The Food Venture Center at Cornell to work with them to further develop verjuice. For now, to develop interest in verjuice, I gave samples to local chefs and asked for their feedback.

Verjuice in the making.

|

Table Grape Production Costs |

Verjuice Production Costs (estimated) |

|||

|

Job |

Total cost ($ 1/8A) |

Job |

Total Cost ($ 1/8A) |

|

|

Pruning |

38 |

Pruning |

38 |

|

|

Shoot thinning |

30 |

Shoot thinning |

30 |

|

|

Summer pruning |

120 |

Summer hedging |

15 |

|

|

Harvest |

165 |

Harvest/press/bottle |

23 |

|

|

Pesticide materials |

45 |

Pesticide materials |

44 |

|

|

Pesticide labor |

90 |

Pesticide labor |

60 |

|

|

Boxes + packaging |

28 |

Bottles |

90 |

|

|

Labels |

9 |

Labels |

9 |

|

|

Delivery |

33 |

Delivery |

8 |

|

|

Mileage |

48 |

Mileage |

14 |

|

|

Call markets |

0.5 |

Call markets |

0.5 |

|

|

Total |

607 |

Total |

331 |

|

Although I couldn't sell verjuice this year, I was successful at making it. To me, it tastes as I remember in my home country. I know from talking with Jim, that there are a lot of cultural differences between Persia and U.S. Many in the U.S. enjoy sweet things, not sour things. I do not want to add sugar to verjuice, because I think it will make it unhealthy.

As a child, I remember there were techniques my mother used to sweeten verjuice that did not include adding sugar. Over the winter, I experimented with those techniques, as well as various types of infusions. I brought samples to the March 15, 2019 verjuice workshop. The feedback is discussed in the education/outreach section below.

Jim has also suggested we meet with other growers he has worked with. Gary and Liz Stone own Red Maple Vineyards in West Park, NY. They are also graduates of the Culinary Institute of America. Jim believes they can offer advice on how to use verjuice in American culture (cooking, mixed drinks, etc.).

I found pressing the grapes in a manual basket press difficult. It also left behind a lot of the grapes, which I felt could still be used to extract more juice. I may try a commercial juicer for the 2019 harvest season.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

Verjuice in the Hudson Valley (presentation)

Jim and I were in frequent communication with each other during this grant. We consulted about vineyard pruning, shoot thinning and pest management decisions. We also discussed adjustments to the IPM program based on higher than expected disease pressure because of heavy rain.

Jim wrote a press release that highlighted the work we are doing at Alistone Vineyard. It was sent out to local media outlets in Ulster County. The press release was also used to write a newsletter article for the Ulster Current. This newsletter is published quarterly. It is a free newsletter that anyone can subscribe to. It is sent out to farmers, educators and the general public interested in agriculture.

Jim gave a presentation about verjuice at the Great Lakes Fruit Worker Conference in Ithaca, NY on November 8, 2018.

In early January 2019, Hudson Valley Magazine reached out to Jim O’Connell for my contact information. They read the press release from Cornell Cooperative Extension of Ulster County and wanted to interview me. I followed up with their editor, Steven Fowler and discussed how with a SARE Farmer Grant and technical advice from CCEUC I was able to make verjuice. We briefly discussed some of the history of verjuice and how I used some family tricks to make my verjuice unique. The article was published in the food and drink section of the May 2019 issue. http://www.hvmag.com/Hudson-Valley-Magazine/May-2019/Verjuice-Ali-Yaghoubi-Stormville/

I spoke with Nasim Alikhani, owner and chef of Sofreh restaurant in Brooklyn, NY. Having Persian heritage herself, she is familiar with Verjuice. She has expressed interest in using my verjuice in her cooking.

I also had a conversation with the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) in Hyde Park about using my verjuice in their foods. They are interested in learning more about my Verjuice and exploring ways we can work together. I have emailed them to schedule a meeting.

On March 12, 2019, the Times Herald Record had a story in their online newspaper about the verjuice I made. https://www.recordonline.com/news/20190312/stormville-grape-grower-reports-progress-in-verjuice-venture.

On March 15, 2019 a workshop presenting a summary of this grant was held at the Hudson Valley Research Lab at 3357 US 9W in Highland, NY. I had planned to hold this event at my vineyard. However, March was colder than I expected and I didn’t have anywhere inside to host the meeting. Five people, including myself and Jim O’Connell were in attendance. Jim O’Connell gave a power point presentation summarizing the work done on this grant. I answered general questions, as well as questions about how verjuice was made in Persia. I also provided samples for tasting. Some were the original recipe, while others were infused with herbs.

I received good feedback. One attendee commented that the verjuice tasted more “alkaline than acidic.” Another felt that a particular herb infused variation would do well as a marinade for salmon. It was also suggested that I look for an intern to help get verjuice ready to sell. The ideal intern would be an enology student. They could communicate with the food venture lab to work out any necessary changes to the verjuice recipe. They could also help with the label design.

Learning Outcomes

As the principal investigator for this grant, I knew about verjuice. I had a family recipe. However, I was not sure how it would do in this country or if I could even make it because the climate and grape cultivars were different. I learned was able to make verjuice and most importantly it tasted similar to my family’s verjuice.

Christian Malsatzki, CCEUC Agricultural Team Leader, surveyed chefs and local food markets in the Hudson Valley. These industry persons were asked about using or selling verjuice. The majority of responses indicated they would not use or sell verjuice. They also responded that verjuice was an unfamiliar product to them and they were unsure how to use it or how the general public might respond to it. This survey helped me realize that the best way to sell verjuice is through familiar markets (i.e. Middle Eastern).

Gary Stone, owner of Red Maple Vineyard and graduate of The Culinary Institute of America, had no previous knowledge of verjuice. As my technical adviser, Jim O’Connell brought him a sample. Gary tried the product and felt that it would be best suited for cooking or possibly for use in mixed drinks. As a salad dressing, Gary felt that it was too thin and would be to runny.

Project Outcomes

This grant proved to me that I can make verjuice in the Hudson Valley that was similar to what I remember from my home in Persia. I believe the verjuice market is still developing. There is still much work that needs to be done in the areas of lab sampling and product labeling, however, I am excited about the future.

Prior to this grant, Jim O’Connell told me that he was unfamiliar with verjuice. I believe that working with him on this project has helped Jim become more educated on verjuice, its uses and potential benefits. I do know that he better understands what verjuice is and how to describe it to people who don’t know what it is.

Because grapes for verjuice are harvested earlier than table grapes, they require fewer pesticide applications and require less input overall. The general public has become more concerned over the use of pesticides in fresh food. Consumers may be happy to know that less pesticides were used to make product.

With this grant, I have answered the initial question of producing verjuice in the Hudson Valley. One of the biggest challenges I faced was that the climate of Stormville is different than Persia and the cultivars used to make verjuice were also different. A challenge, which I haven’t overcome yet, is pressing the grapes. The basket press did not appear to press the grapes enough. I plan to look into a juicer. The problem is the volume of grapes. A home juicer is too small and will probably take too long. Many of the commercial juicers I looked at are bigger, but they don’t recommend operating for long periods of time. I am concerned that even though they are bigger, they still won’t be able to handle the volume of grapes.

I estimated sales of verjuice for this grant. When I started this project, I thought I would be able to sell verjuice by early 2019. I did not realize the process of bringing a new product to market would be so complex. The verjuice needs to be tested to make sure it’s safe. The labeling process is also involved and has many specific legal requirements. I have started the processes needed to sell verjuice. Looking back, would have started process with food venture lab earlier so I could have sold verjuice in 2019.