Final report for FNE19-933

Project Information

This project sought to establish more robust seedling establishing methods for northeastern rice production that allow to shorten the rice production cycle, as well as to increase rice productivity and farm benefit. We tested and compared the Diolla-style(AKA Jola-style) field nursery method with the Akaogi plug-tray nursery method, in staggered planting, and using two varieties of rice. The eight treatments were repeated three times in three paddies. Our findings show that we were able to extend the window to transplant and shorten the production cycle by using the Diolla-style nursery bed. We observed that seedlings started later and transplanted at a younger stage were more resilient; paddies transplanted as late as June 30 reached maturity. Over the course of the experiment we hosted over 200 people at community transplant days, community harvest days, school trips, farmer organization field trips and frequent visitors. The video and article produced by Cornell University and posted on its website sparked wide interest. These outreach efforts let to additional interviews and articles in the local and national press exposing our work into even larger audiences.

This project sought to: identify more robust seedling establishing methods for northeastern rice production that allow to shorten the rice production cycle, as well as to increase rice productivity and farm benefit.

We tested two nursery methods, the Diolla-style field nursery method and compared it to the Akaogi plug-tray nursery method. This was done at two seeding and transplanting dates for each method and combined with testing two varieties. We evaluated plant development at different stages, grain yield. The two varieties were: Duborskian, an Asian rice variety, widely grown in the Northeast, and Ceenowa, an African rice variety, our commercial flagship variety.

We hypothesized that if the project was successful and the Diolla-style field nursery was well adapted to the northeastern region, it would allow to considerably shorten the crop production cycle. With transplanting younger seedlings compared to previously established methods, we expected it to result in an increase in rice productivity. Both outcomes should be of of direct interest to most rice growers in the Northeast. As the Diolla-style field nursery method is a simplification of the current establishment methods and is not depended on costly materials, farmers would most likely find it easy to adopt.

Rice is a staple crop for more than one half of the world’s population. Northeastern farmers have the potential to contribute to their communities’ needs for this grain while simultaneously minimizing the carbon footprint imports make. Ever since the Akaogi’s demonstrated that rice can be grown in Vermont, interest among northeastern farmers has grown (Akaogi, 2009). However, emergent growers can’t expand production without a better understanding of nursery practices.

The types of rice successfully grown in the Northeast are mostly of northern Japanese descent in addition to the Bulgarian variety Duborskian. At Ever-Growing Family Farm, we began growing rice in 2015 and launched the Hudson Valley Rice Project (HVRP). We started out with two Asian varieties, Akitatomachi, Koshkikari and one African variety, Ceenowa, using the guidelines and methods developed by the Akaogi’s. Since then we have added other varieties: Duborskian, Nanatsuboshi, Loto, Arpa Shali. Although we were successful growing the crop, we were confronted with a number of constraints, summarized as follows:

- The growing season in the Northeast is short, especially for rice - a warmth loving crop. The window of operation in the spring is very short to assure that the crop is established in the field early enough but without being damaged by a cold spell. When planted too late, the crop will not be able to set grain and harvest is not guaranteed.

- The number of rice varieties adapted to the northeastern climate is still limited, especially when faced with the difficult environmental conditions for growing rice in the northeast.

Ever-Growing Family Farm (EGFF) is a small farm in the Hudson Valley of NY owned by Dawn Hoyte, and husband Nfamara Badjie. In 2014 EGFF began growing vegetables and rice and raising livestock. While we have not sought organic certification, we adhere to those principals. Since 2015, together with our cousin Moustapha Diedhiou and son Malick, we ran a CSA and grew commercial rice. In 2018 we decided to focus solely on rice both due to its popularity and to rice farming being our cultural heritage. We have 18 established paddies. We harvested about 1400 pounds in 2018. In 2019 the yield increased by about 300 lbs. We keep chickens for manure. In 2018 we added ducks to weed select paddies inspired by the work of Erik Andrus, Boundbrook Farm, Vt. Our rice is sold from the farm; packaged by early November, it usually sells out by January. Nfamara, Moustapha and Malick, assisted by Modou (17) and Abibou (15), are all members of the Diolla tribe of the Senegambia region, grew up as subsistence farmers. Rice is intrinsic to Diolla culture and they bring that love, respect and knowledge to their work as they carry forward their cultural legacy. Over the past several years we have used all the farm income to rent or purchase equipment. We now own a BCS walk-behind tractor with a rototiller we use to cultivate the paddy soil. We rent a bobcat and use a traditional Diolla hand shovel to create the paddies. Through an online Gofundme campaign and with help from our dear friend and amazing rice farmer, Erik Andrus, we have imported from Japan a used milling machine and a rice polisher. This year we used all the money we earned from conducting the grant to buy a small used rice combine and rice dryer from Japan. The combine has changed our life! Before the combine we hung the rice to dry; it then was hand threshed and wind-winnowed. The combine saved us thousands of hours of hard physical labor. Outside the farm, we all work full-time jobs. Our hope is that soon at least one of the farmers can farm full-time. Our rice has gained a reputation for its flavor, texture and freshness. As a result, consumers contact us in late October asking if the rice is ready. We sell out, from on farm sales, by January. Although multiple restaurants and retailers have requested our product, we have thus far chosen to cater to the needs of individual community members. Regrettably, though the market is proven, we currently cannot meet the demand.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor (Educator)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

Research

METHODOLOGY

Experiment location: A field experiment was set up during the growing season of 2019 at the Ever-Growing Family Farm in Ulster Park, in New York’s Hudson Valley.

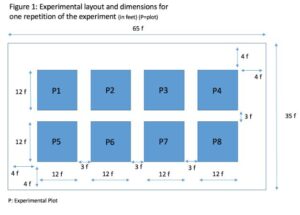

The experimental design was a randomized block design with 8 treatments and 3 replications. Three out of the 18 Ever-growing Family Farm paddy fields were selected for the experiment. Each of the three paddies represented a block (B1-3) and a repetition (R1-3). Paddy sizes were for R1: 70 feet x 45 feet, R2: 70 feet x 45 feet, and for R3: 69 feet x 66 feet. The experimental block with a 4 feet boundary was 65 feet x 35 feet, thus fit well within each of the three paddies. The experimental layout, with assigned treatments, and the plot layout and dimensions are shown in Figure 1.

Paddy characteristics: all paddies were created in 2015, and rice was grown there for 3 years previous to this experiment. The composition of the soil is mostly clay-based. There is full water control for irrigation for all three paddies. Irrigation water is accessed from a stream-fed pond and plots can be drained if necessary. Previous rice crops have shown uniform crop growth in each of the paddies, which makes them suitable as blocks.

Treatments

Treatments included three elements: a) nursery types, b) time of sowing and transplanting, and c) rice varieties.

a) Nursery types: i) Akaogi nursery (A), ii) Diolla nursery (D)

b) Timing of sowing and transplanting: i) normal seeding and transplanting (first planting =1), ii) late seeding and transplanting (second planting = 2)

c) Rice varieties: i) Duborskian (D): a widely-grown reference variety for the Northeast; ii) Ceenova (C), the farm’s commercial flagship variety.

T1: Akaogi 1, Duborskian, A1D

T2: Akaogi 1, Ceenova A1C

T3: Akaogi 2, Duborskian A2D

T4: Akaogi 2, Ceenova A2C

T5: Diolla 1, Duborskian D1D

T6: Diolla 1, Ceenova D1C

T7: Diolla 2, Duborskian D2D

T8: Diolla 2, Ceenova D2C

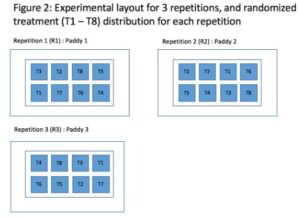

The randomized treatment distribution in the three paddies is shown in Figure 2:

Explanation of the treatments:

- Nursery types: i) Akaogi nursery (A), ii) Diolla nursery (D)

Akaogi plug tray nursery method: For the Northeastern region of the USA, the Akaogi method was so far the reference method for establishing the rice plants and for growing rice developed by the Akaogi family in Vermont (Akaogi, 2009b).

How to do it: Soak seeds for 7-10 days, change water daily and discard seeds that float to water surface. Fill cell trays with wet growing medium. Sow 2 seeds per cell. Place trays in hoop house. If nighttime temperatures drop below freezing, cover and/or use external heat source such as a space heater in the hoop house. Keep trays wet. Transplant after 30 days.

Diolla field nursery method: This is a modification of the traditional Diolla practice, where nurseries are installed as raised beds next to the rice paddies. Very similarly, raised bed nurseries are also part of the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) rice growing method practiced currently in 55 countries.

How to do it: Soak seeds for one or two days (change water after one day) and discard floating seeds. Drain water, remove seeds and wrap them in a burlap bag. Keep seeds in a warm spot for 24 hours for pre-germination. Construct field nursery beds by laying cardboard on the ground and topping it with a growing mixture, creating a 6-inch deep raised bed, in which seeds are sown. The bed is covered with rice straw mulch and row cover to prevent seed loss to birds until the seedlings reach a 3-inch height and are safe. Beds are watered with a watering can as needed to keep the soil moist. Seedlings are transplanted after 15 days, at 2-3 leaf stage.

- Timing of sowing and transplanting: i) normal seeding and transplanting (first planting =1), ii) late seeding and transplanting (second planting = 2)

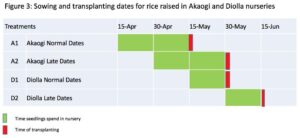

Seeding and transplanting dates were staggered for the two nursery methods, as shown in Figure 3. The normal Akaogi seeds were sown mid-April, the late Akaogi seeding was done at the end of April. These are relatively early dates, as mid-April the weather can still be fairly cold, and plants are in need of a hoop house.

As the Diolla seedlings are younger, the seeding can happen later and directly into the ground, without the need of a hoop house. We timed the planting of the normal Diolla nursery, with the late Akaogi nursery. In order to push the time of seeding and transplanting even further into the growing season, we added a fourth time of seeding, late Diolla, at the end of May with a late transplanting planting of mid-June.

Transplanting:

- Planting distance between hills was 10”x 10” in all eight treatments

- The seedlings in the Akaogi treatments were planted at 2-3 seedlings/hill, as recommended by the Akaogi manual.

- The seedlings in the Diolla treatments were planted at one seedling/hill, following the reason that younger seedlings have a higher tillering capacity compared to older seedlings, a confirmed finding in the SRI scientific literature. Using one seedling instead of 2-3 seedlings also allowed to save half to two-thirds of seed.

Rice varieties:

Duborskian (D) is a widely-grown reference variety from Russia, and well adapted to the North-East of the USA.

Ceenova (C) is the Ever-Growing Family Farm’s commercial flagship variety from West Africa

Crop Management:

All plots received the same crop management interventions.

- Soil preparation: uniform soil preparation in all three paddies, with special attention to leveling the paddies, to assure uniform water distribution across the experimental layout during irrigation.

- Fertilization: equal amounts of composted chicken manure applied to the three paddies, mixed in with soil prior to planting.

- Weeding: was done as needed, plucking weeds at young stage, ensuring the plots remain unharmed by weed competition

- Irrigation management: an alternate wetting and drying irrigation regime was applied to all the plots.

Measurements:

- Date of seed soaking

- Date of seed sowing

- Date of seedling emergence

- Seedling growth in nursery: seedling height, color and date of leaf emergence was recorded every five days from the date of sowing; 10 seedlings were randomly selected/treatment

- Date of transplanting

- Seedling characteristics at date of transplanting: seedling height, leave numbers, root length, vigor, leaf color. 10 seedlings were randomly selected and measured for each treatment.

- Number of tillers/hill at 20 days, 40 days and 60 days after transplanting. 10 plants were randomly selected in each plot and tillers counted.

- Date of flowering

- Date of maturity (maturity and harvest dates did not always coincide. Depending on labor availability, some plots were left standing a few days beyond maturity before harvesting)

- Date of harvest

- Yield of unhulled paddy grains (of the entire experimental plot, after drying and threshing)

- Yield parameters: Number of tillers/hill, number of panicles/hill (10 plants will be randomly selected in each plot), and length of panicles (3 panicles were randomly selected from each plot)

- Monitor nursery and crop management operational costs for each treatment

- Cost/benefit analysis for each treatment

Data analysis:

The Duborksian rice plants experienced a high mortality rate, for non-explicable reasons. Some of the plots (repetitions of treatments) were entirely lost, especially for the Akaogi treatments. For this reason, results are reported with simple graphs and based on field observations and not on statistical analysis.

RESULTS: Calendar/timing of crop development

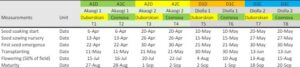

The observations collected for different parameters are described below. The dates and number of days for each crop cycle stage for all the eight treatments are regrouped in Table 1a and 1b, and shown in Figure 4 and 5.

Table 1a: Dates of crop establishment and development for the eight treatments

Table 1b: Number of days of crop cycle stages for the eight treatments

Seed soaking extended between 5 and 7 days for the different treatments.

The emergence of seedlings was between 3 and 9 days after sowing, for A1 being 9 days, followed by D1 by 6 days, then A2 by 4 days and D2 with 3 days only. As the season got warmer, the seed germinated faster, although A2 was seeded before D1, but greenhouse might have been warmer at that time than the raised beds environment.

Age of seedlings at transplanting was for the Akaogi treatments 25 days (A2) and 28 days (A1) after sowing, and for the Diolla treatments, seedlings were 15 days (D1) and 17 days (D2) old at transplanting. This was very close to the protocol of 15 and 30 day old seedlings for D and A treatments, respectively.

Time of flowering: The different treatments flowered between 61 days and 72 days after transplanting, with D1C being an outlier with 72 days, whereas all other treatments flowered after 61 and 66 days.

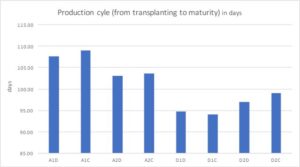

Plant production cycle: Maturity for harvest was reached at different time intervals after transplanting. The Diolla treatments matured faster than the Akaogi treatments, with between 94 to 99 days after transplanting, whereas for the Akaogi treatments this was between 103 and 109 days after transplanting. The Diolla treatments gained 10 days in the production cycle over the Akaogi treatments after the time of transplanting.

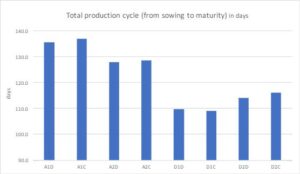

In regards to the entire production cycle from the time of sowing to maturity, the Diolla treatments gained an additional 10 days. This is because the Diolla seedlings were only 15-17 days old when transplanted compared to 25-28 days for the Akaogi seedlings.

Saving a total of 20 days in the production cycle from sowing to maturity is a remarkable result. Difference between Normal Diolla and Normal Akaogi reached even 25 days. Diolla normal sowing performed best and was followed by Diolla late sowing. In third place was Akaogi late sowing and longest cycles were achieved with Akaogi normal sowing. Both varieties responded very similarly in respect to nursery treatment, with Ceenova having overall a slightly longer production cycle. These results are illustrated in Figure 4 and 5.

These results are very similar to findings from SRI fields in different countries, where it has been repeatedly shown that SRI rice plants (young seedlings, single plant/hill with wide spacing between hills) mature up to 2 weeks faster than conventionally grown plants (older seedlings, several plants/hill in close spacing).

Figure 4: Production cycle from transplanting to maturing for eight treatments (in days)

Figure 5: Total production cycle from sowing to maturing for eight treatments (in days)

Seedling development in the nursery

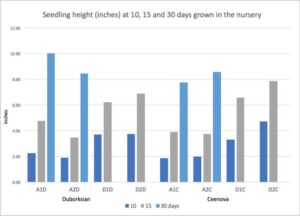

Seedling heights in the nursery at 10,15 and 30 days after sowing is shown in Figure 6. The Akaogi treatments remained in nursery for 1 month whereas Diolla treatments for only 15 days.

Figure 6: Seedling height at 10,15 and 30 days grown in the nursery (in inches)

All seedlings in the Diolla nursery had a faster growth than the seedlings in the Akaogi nurseries. At 10 and at 15 days the Diolla seedlings had about a 5-day advantage over the Akaogi seedlings. For Ceenova, the late Diolla planting produced seedlings of 8 inches in height within 15 days, which was almost the same height the late Akaogi seedlings reached in 30 days.

The faster growth in the Diolla nursery can be explained by at least two main factors:

- When starting later in the season, the average temperatures are higher and germination and initial growth is faster.

- The raised bed nursery provides a better soil medium for the roots to develop in, with more and deeper space for growth, compared to the trays with the small plugs, where the roots don’t find much room to grow in. The plugs are also surrounded by air; thus temperature fluctuation is higher compared to seedlings grown in the soil bed.

It would be interesting to repeat the seedling establishment growth next season, including sowing the Akaogi and Diolla nurseries at the same times.

- Tiller development

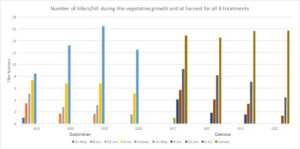

Tillers were counted four times, three times every two weeks during the vegetative stage of the plants, and then again at the harvest. Of note: the Diolla planting method used 1 seedling/hill (according to the SRI method) compared to 2-3 seedlings/hill for Akaogi plantings. The results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Number of tillers/hill during vegetative growth stage and at harvest for all eight treatments

During the early growth and development of the plants in June until early July, the results indicate clearly that the earlier planted treatments had a higher number of tillers than the later planted treatments or: A1 > A2 > D1 > D2. This was the case for both varieties.

But until harvest, the later planted treatments caught up with the earlier planted treatments reaching similar number of tillers/hill especially for the Ceenova variety. The Diolla nursery treatments for Ceenova exceeded the Akaogi nursery treatments slightly 15.65 tillers/hill for D1C and 15.7 numbers of tillers/ hill for D2C, whereas the A1C reached 14.87 tillers/hill and A2C 14.53 tillers per hill.

As the Duborskian variety experienced a high mortality, especially for earlier plantings and the Akaogi nurseries, it does not allow for an easy interpretation of results at the harvest stage. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that the normal Diolla nursery treatment achieved highest tiller number for Duborskian with 16.45 tillers/hill.

- Panicle length at harvest

Panicle length at harvest for all eight treatments is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Panicle length (in cm) at harvest for all eight treatments.

Due to high mortality and missing plots for the Duborskian variety, interpretation of data is not done. For the Ceenova variety, the data seem to indicate that the normal Diolla nursery produced longest panicles, followed by the late Diolla nursery and the Akaogi late plantings.

- Paddy grain yield

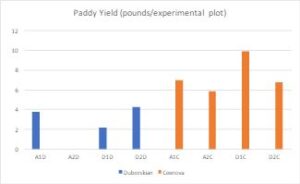

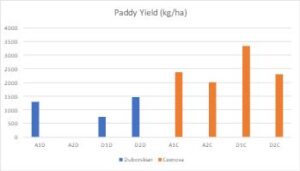

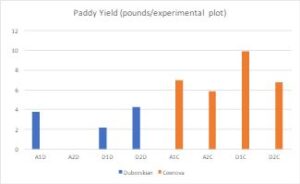

The paddy grain yield for all eight treatments is presented in the Figure 9a) in pounds of paddy grain/experimental plot, and in Figure 9b) in kg/ha.

Figure 9: Paddy grain yield for all eight treatments in pounds/experimental plot (a), and in kg/ha (b)

As with panicle length, due to high mortality and missing plots for the Duborskian variety, interpretation of data is not done.

- Highest yield was obtained in D1C with 9.9 pounds, followed by A1C with 7.0 pounds, D2C with 6.8 pounds and A2C with 5.9 pounds.

OR

- Highest yield was obtained in D1C with 3346 kg/ha, followed by A1C with 2366 kg/ha, D2C with 2298 kg/ha and A2C with 1994 kg/ha.

Additionally, yields for the Ceenova variety show that the average of the two Diolla/SRI treatments obtained higher yields with 2822 kg/ha compared to the two Akaogi/conventional treatments with 2180 kg/ha.

CONCLUSION

The Diolla/SRI method produced a number of advantages over the Akaogi/conventional method, which are summarized as follows:

- Planting only one seedling/hill instead of 2-3 seedlings/hill allowed to save half to two-thirds of seed.

- Diolla treatments matured 10 days faster from time of transplanting to maturing and 20 days faster from sowing to maturing. The rice crop started with the normal Diolla nursery gained even 25 days over the crop established with the normal Akaogi nursery. A dramatically shorter crop cycle allows for much greater flexibility in timing the establishment of the rice crop. This has so far been the big bottleneck for rice production in the Northeast. Nurseries can be started later, and the option to stagger nurseries over a longer time period than previously believed, allows the farmers more flexibility, while still obtaining a good yield.

- The best treatment in our experiment was the first Diolla nursery that was seeded mid-May and transplanted at the end of May/early June. This was supported by the various measured parameters, such as fast seedling growth in the nursery, high tiller numbers/hill, longest panicles and highest paddy grain yield.

- This indicates that in the Hudson Valley, there is no need to grow seedlings in plug-trays and in a hoop house, but the seedlings can be directly grown in raised beds, which reduces input costs and labor substantially. The seedlings grown in raised beds had the advantages of being transplanted as single seedlings at young age, experiencing minimal transplanting shock and less competition, which allowed for a quick healthy plant growth, also favored by the warmer soil and air temperatures in June.

The innovative practice of growing seedlings directly in the field on raised beds, as informed and inspired by the traditional Diolla practice and the SRI method, created very positive results. This is in contrast to the recommended nursery method for the Northeast of the USA developed by the Akaogi family farm in Vermont, which uses plug-trays set in hoop houses to produce the rice seedlings. It is clear that the climate in the Hudson Valley is milder than in Vermont, and that the results from this experiment might not be directly transferred to Vermont conditions. But our findings allow to broaden the range of technical options how to establish and grow rice successfully in the North East. Our experience should provide other growers with new ideas to work with, and to adjust and adapt the techniques to their own local environment. To confirm and further fine-tune best nursery establishment practices for the Hudson Valley environment, we plan to repeat this experiment slightly modified on EGFF in the upcoming season.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Farm visits, community attendance at farm events, articles in local press, on-line journals, and regional publications, local speaking invitations and widespread interest in our project far exceeded our expectations. Every week, announced and surprise agriculture enthusiasts, local food lovers, gardeners and small-scale farmers toured our farm. Highlights include the following:

May 30 - Woodstock Day School Tour and transplant: Farmer Nfamara led a class of 7th grade students in a hands-on educational experience. Students were given a tour of experimental paddies and nurseries, the experiment was explained. Student used planting grids made to facilitate SRI spacing consistent with the research paddies, and transplanted an auxiliary paddy of Duborskian rice. They returned in the fall to harvest the paddy they planted.

June 1 and June 15 - Community Transplant Days: Over the course of two weekends more than 50 participants were given a tour of the SARE grant paddies and nursery/hoop house seedlings. The experiment was explained. Participants were led in a hands-on demonstration of rice transplanting. Education was provided on the two starting methods utilized in the grant and participants engaged in transplanting in auxiliary paddies utilizing SRI spacing and consistent with one trial method of the experiment. Attendees came from as far as NYC and included educators from Randall's Island Park Alliance Edible Education Program.

July 13 - Cornell University visit: Dr. Susan Mccouch and others from Cornell University spent the day at the farm, observing the project, taking rice samples, and sharing rice knowledge and experiences. An article on the farm appears on the Cornell University website.

https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2019/10/african-rice-farmers-test-traditions-against-ny-climate

August 13 - Tour: Caryl Levine and Ken Lee owners of Lotus Foods: Rice is Life were given a tour of the experimental paddies and our observations to date were explained. Lotus Foods is a Richmond, California, based company that focuses on importing handcrafted rice from small family farms to the United States. They are interested in growing rice in the northeast.

August 18 - Reher Center for Immigrant Culture and History, Kingston NY, Presentation: "Same Rice, Different Land". Nfamara and Moustapha gave a presentation on the work being conducted through the SARE grant on the farm to local agriculture and immigrant culture enthusiasts.

August 19 - RVGA (Rondout Valley Growers Association) Panel Discussion "Growing With the Grain": EGFF participated in panel discussion at Arrowood Farm Brewery, Accord, NY, with local grain activists regarding the resurgence of sustainable grain production in the region. Nfamara, Moustapha and Dawn spoke about the SARE grant work. Over 200 local farmers and supporters attended.

Sept. 28 - Community Rice Harvest: Over 70 participants including nationals from Senegal, Gambia, Egypt, India, Canada, France, as well as folks from the tri-state area and NYC participated in a hands-on demonstration of rice harvesting accompanied by drumming, signing and agri-cultural education. SARE grant paddies were toured; explanation of the experiment and observations to date were provided. Participants included a tour group with Loren Cardeli, founder of A Growing Culture, an international non-profit that supports farmer-led research and advocacy. Cardeli brought NYU students and renowned Indian rice farmer Deba Deb. The event was publicized in the RVGA (Rondout Valley Growers Association) online publication which brought local farmers. Flyer was provided. Event was recorded live for Gambia TV.

Oct 25 - BUGS (Black Farmers and Urban Growers) 2019 Conference tour: Approximately 25 farmers and conference attendees spent the day learning about the SARE grant experiment. Their blurb: Rice and Community with Ever Growing Family Farm — Rice and Community with Ever Growing Family Farm — Located in Ulster Park, NY, Ever Growing Family Farm is a small farm run by master rice farmers from the Senegambian region of West Africa, who have been growing both African (Oryza glaberrima) and Asian (Oryza sativa) varieties of rice in New York's Hudson Valley since 2015. Over the years they have combined their own ancestral Diolla rice farming practices with rice farming practices from other regions of the world, to develop agroecological techniques catered to growing rice in the temperate Northeast. This farm visit will include a tour, some demonstrations of their farming and harvesting methods, as well as some farm work for those interested.

Oct 25 - Bruderhoff Community student tour - hands-on harvest tour and educational field trip for students from the Bruderhoff Community. The community grows all their own food. SARE grant activities and observations were explained.

Jan. 2020 - Kingston High School presentation: Nfamara presented to students involved in a sustainable agriculture class. Plans are for students to participate in hands-on learning on the farm this spring.

Feb. 21, 2020 - "Land in Black Hands" program, Kingston, NY: Nfamara and Dawn participated in a discussion on land sovereignty and food security, explaining the work being done on the farm as it relates to implementing sustainable local food production. (50+ attendees)

Additionally through-out the season many impromptu visitors were provided tours of the trial paddies and research project. Student farmer, Abibou Badjie, presented on the experiment from his perspective at multiple youth venues in Kingston, NY..

Learning Outcomes

Most farmers who visited the farm had little or no experience with growing rice. That said, everything from how to best start rice (time and method), to the best time and method to transplant through paddy determining harvesting readiness was explained. Additionally, farmers were provided information on how to construct paddies, how to design nursery beds as well as the advantages and disadvantages of various varieties of rice, starting and nursery methods, transplant times including the advantages of SRI spacing awareness. As a result, more than 20 beginning and aspiring farmers committed to participate in the coming season in order to acquire the skills. In particular, members of BUGS (Black Urban Growers), and affiliates of the Farm Hub (Ulster County), reported they plan to participate next season. Seed was provided to educators from Randall’s Island Park Alliance Edible Education Program for use in their educational farm in NYC.

Project Outcomes

We at Ever-Growing Family Farm observed that seedlings started using what were termed "the Diolla" method of nursery beds, though started later and transplanted at a younger age, were more robust. Transplanting the smaller seedlings is more time-consuming as greater care is needed. This is a draw-back and although we transplant by hand, given the fragility of younger seedlings, we do not believe it would lend itself to mechanical transplanting. A noticeable benefit was that the smaller "Diolla" style seedlings recovered faster. They required less time for care prior to transplant. More care was required in monitoring paddy water levels as they were much shorter than the "Asogi" tray method seedlings.

We at EGFF extended our season, transplanting the experimental plots as late as June 8 and additional paddies through June 30. All paddies reached maturity. We learned that the by transplanting over this long period we could harvest over a longer period. As mentioned earlier in this report, there are advantages to utilizing the tray and field nursery methods in tandem to achieve a longer window to transplant. We plan to start with trays in mid-April and switch to field nurseries by early May. Additionally, rather than starting as many seedlings as our hoop house and field nurseries could hold at one time, we will stagger our seeding so as to only start what we can transplant on a given date. Thus, we will have a continuous supply of younger seedlings which appear to be more resilient. Furthermore, we will avoid loss of seedlings to stress and therefore use less seeds, starting only what we can transplant before they yellow. As a result of this project, by implementing staggered seed starting, transplanting younger seedlings, one per hole with 12 inch spacing we expect to increase our rice yield using less seed.

Due to the widespread media attention, we were able to share both and agricultural and our cultural practices with a large and diverse population. We look forward to expanding and strengthening the ties of this agri-cultural community.

Anecdotal observations: Through observations made during the project, we extended our season by continuing to transplant until much later than prior years. We transplanted experiment plots through early June. Observing how quickly the "D" field nursery transplants caught up, we continued transplanting through the end of June. All rice reached maturity. The staggered and extended transplanting time allowed for an easier harvest as it was spread over a longer period of time.

We observed the field nursery required less time: seedlings did not need to be watered as frequently and were transplanted earlier. Although we already owned plug-trays, had we needed to purchase them, the field nursery method would have saved money. By extending the transplanting time over a 1 1/2 month period we were able to involve more community members and organizations in the process. Therefore, a secondary goal of community agricultural and cultural education was achieved to a greater extent than previous years. By reducing to 1 seedling per hill (as in SRI) we required less seed.

By starting seeds in succession over a longer period of time we were able to transplant seedlings before they experienced stress. In an other area of the farm Malick created and seeded nursery beds early in the season. We observed that when his seedlings reached an age of 4 weeks they began to yellow, many were lost because they could not be transplanted quickly. It appears that while transplanting seedlings at a very small size requires more care (and therefore more time), the seedlings are healthier and therefore recover more quickly. This was observed for both field nursery and tray seedlings.

Utilizing both the tray and field nursery methods enables the longest transplanting window. Moreover, staggering the starting of seeds, so that that seedlings can be transplanted between the optimum size of 2-3 leaf and the maximum height of 6 inches, results in less seedling loss, greater transplant resiliency, and lower seed cost. As a result of our observances during this project, we will now start seeds in smaller batches ocontinually over a longer period of time, starting only what can be transplanted at the optimal size and a projected date.

We encountered several unforeseen challenges: This year we experienced high weed growth in R1 and heavy bird impact on R2. Paddies that remained flooded over the winter experienced less weed growth. Additionally, some plots thrived while others failed with no apparent reason. Ceenowa suffered more from bird loss. It is particularly attractive to birds as it "shatters," meaning falls from the stalk easily. Birds recognize that it makes for easy picking. We planted other varieties in addition to those in the experiment. We tried a red rice that birds preyed on in the milk stage. The birds sucked the milk from the grains. They stopped when the rice had reached the hard stage. We tried a variety of bird deterrents: strung old video tape that whistles and reflects, staked plastic owls, hung cloths. We researched bird nets as used in grape production, but they are really costly. Bird impacts varied from paddy to paddy, with some completely spared. For the upcoming growing season, we will plant the variety favored by birds in the center of the less favored. We observed that birds do not like Duborskian rice which has long awns and is strongly adhered to the stalk. Further research in preventing loss to birds is needed.

Community involvement and education was significant. In past years we transplanted by eye. This year under the tutelage of our advisor, we used a grid in the experimental paddies to ensure exact spacing. During the community transplant days, guide poles made out of PVC were used to guide participants. We observed that utilizing these guides not only helped visitors plant in straight lines, but sped up the process for veteran farmers also. It is a practice we will continue. Due to the press the project received, we attracted many more visitors to the farm and we able to to educate many people on rice farming. The interest in growing this staple crop is great. We will be holding many more community education days. Community events also provided an opportunity for cultural exchange and fostered intercultural respect and appreciation.