Final report for FNE20-968

Project Information

Estimates suggest that sheep account for roughly 8% of global anthropogenic methane emissions, a massive contributor to build-up of greenhouse gases. While methane is far more potent than carbon dioxide, its atmospheric impact declines significantly after only 10 years, which suggests relatively short-term benefits can be achieved by acting now. In this report we seek to refine and extend current research into the use of Asparagopsis taxiformis as a feed additive to reduce methane expulsion by sheep.

Our research had three objectives:

1.Assess methane expulsion over a six-week period using 0.0% (control), 0.25%, and 1% Asparagopsis taxiformis DMI (dry matter intake) levels.

2.Examine changes in the well-being of the three groups using a variety of parasite counts as a proxy.

3.Explore correlation of observed methane and parasite results with sheep microbiome composition and diversity.

Originally we planned to give 0.5% and 2% DME but at the beginning of the project decided to decrease the dosage. The reason was possible constraint in the production by Symbrosia of the seaweed powder at that moment. In order to secure a sufficient amount of the seaweed for the duration of the project, we reduced the amount we would use. So the animals actually were given 0.25% and 1% for low and high supplementation groups respectively.

Consistent with the initial hypothesis, we found 50-70% reduction in methane expulsion when using 1% Asparagopsis DMI, with 93% of the sheep showing improvement after only 3 weeks. However, in a departure with prior studies we found impact at 0.25% DMI dosing more limited. Observed decline in methane for 1% DMI cohort was supported (and partly explained) by statistically significant, 32% decline in Archaea methanogenic organisms. However, our most exciting findings came from analysis of sheep parasites, which we believe is the first time such research was published. We found that the use of Asparagopsis had a significant anti-parasitic effect. We observed statistically significant reduction at both 0.25% and 1% dosing levels, with both Eimeria and Strongyles parasites exhibiting declines. We examined both egg counts in fecal matter, as well as cultured samples and found confirmation in both approaches. Surprisingly, lower, 0.25%, dose had faster and more significant anti-parasitic benefit. This could have favorable commercial implications given production capacity constraints we are seeing today. It is important to note that given the lack of prior studies, our research was not explicitly structured to test for anti-parasitic properties. Instead, it was found as part of overall sheep health investigation. We were also very encouraged by the fact that treatment groups experienced 1% faster weight gain versus Control.

Examination of microbiome showed statistically significant increase of beneficial Butyrivibrio bacteria for 0.25% cohort. Effect was only marginally significant for the 1% group. We also observed a significant decline in Peptostreptococcaceae bacteria for 1% DMI cohort, which seems to suggest direct antimicrobial impact at higher dose levels. There was a significant decline in Ruminococcus genera in both intervention groups which might signify a shift to lower Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio and less production of fermentation compounds that might be substrates for methane synthesis.

Results to-date are extremely exciting – at least, raising the potential that methane reduction can be achieved, while improving parasite loading and increasing weight gain and beneficial gut bacteria. There are several topics that require further study, with most important being appropriate dosing that balances methane reduction against potentially higher antimicrobial effect. Results also need to be replicated outside of an organic farm, to show efficacy with the traditional commercial farming methods.

Three groups of investigated animals were :

1.Control group( 16 Whiteface organic grass fed sheep)(1.5 year old, non pregnant) - that were not given any seaweed for 6 weeks

2.Group 1(16 Whiteface organic grass fed sheep) (1.5 year old, non pregnant) were given 0.25% of DMI seaweed a day for 6 weeks

3.Group 3(16 Whiteface organic grass fed sheep)(1.5 year old, non pregnant) were given 1% of DMI seaweed a day for 6 weeks.

The first goal of the project is to find an answer if an addition of red seaweed Asparagopsis taxiformis 0.25%DMI or 1%DMI of organic matter to feed of the pasture raised organic sheep would help to control environmentally harmful methane emissions. The second goal was to check supplement's long term effect on animals health, integrative parasite control, body score composition and microbial diversity of the intestine in addition to its reduction of methane output and help in mitigating global climate change.

Methane CH4 is a greenhouse promoting gas that is a natural product of digestion and fermentation in the stomachs of grazing animals. It is normally produced in the rumen by special methanogenic bacteria that accept extra hydrogen gas molecules formed after fermentation of the cellulose and carbohydrates by fibrolytic and amylolytic bacteria. In this way it protects animals from ruminal hydrogen gas accumulation that would decrease digestive efficiency, inhibit activity of rumen enzymes, and bring danger to overall health. Ruminant animals have the unique ability to digest cellulose and lignin by specialized bacteria in their digestive tract, convert them into short chain fatty acids (propionate, butyrate and acetate), absorb them into the circulation, which is then used for energy balance, growth and metabolism (Ferry, 2011; Macfarlane, 2003). However, excessive production of the methane means that beneficial metabolites are not converted into the Short Chain Fatty acids, and instead of being used for productive energy needs, are diverted into the methane and get excreted. There is an irreversible loss of 2.3% of potentially useful metabolites for every 1 kg of Dry Matter intake, which signifies losses of animal productivity and ultimately decrease in profitability of the farms (Niu et al, 2018). Methane production in the rumen is shown to positively correlate with animal weight, dry matter intake, NDF digestibility, simple sugars and carbohydrates in the diet and negatively correlate with fatty acids intake (Niu et al, 2018). There have been ongoing efforts to reduce methane emission by changing animal feed. Several additives were studied over the years, including nitrates, tannins, saponins, essential fatty acids, ionophores, chemical synthetic bromoform. Other strategies were employed as well such as vaccinations and strategic breeding for genetically less methane producing breeds. Reported methane reduction ranged from 10% to 39% (Williams, 2010; McGinn, 2004; Patra, 2010; Goel, 2012; Cottle,2011). In some studies (particularly with synthetic bromoform) the methane reducing ability gradually declined over time suggesting potential bacterial adaptation of the rumen bacteria that evolved genetically to counteract the trend (Patra, 2017; Belanche, 2019).

Several research studies demonstrated that red seaweed Asparagopsis Taxiformis significantly (40 to 90%) decreased methane production in the rumen of cows, sheep and goats both in vivo and in vitro (Machado, 2014; Kinley, 2016; Roque, 2019; Machado, 2015; Machado, 2016). The mechanism of methane reducing action of the red seaweed is alteration of the microflora of the rumen with the shift of the microbiome into bacterial species producing more hydrogen gas and CO2, instead of CH4. There was no decline of methane reduction over time, but longer-term studies are needed (Machado, 2016). Red algae administration at a 0.5% to 5% DMI was effective at methane reduction, but slightly reduced short fatty acids production for >2% of DMI, and adversely affected organic matter digestibility at doses higher than 3% DMI (Xixi Li, 2016). The supplementation also shifted short fatty acids into higher propionate production. Propionate synthesis serves as an alternative hydrogen acceptor or “sink” and successfully competes with the methane producing pathway in this scenario. All previous in vivo studies were done on commercial conventional farms where animals were kept in the feedlots and raised on conserved forages in addition to the concentrated feed. It was shown previously that the concentrated feed and grains are more digestible than forages and can decrease rumen PH, cause more propionate rather than acetate synthesis, less cellulolytic hydrolysis and less methane production. There is no agreement on an appropriate dosage of the red seaweed supplement – in vivo studies point to range between 0.5% and 2% (Roque, 2019); in vitro suggest around 2% (Vijn, 2020). Our study was designed to examine the dosing of 0.25% and 1% DMI of red seaweed in pasture based production system. The goal is to achieve sufficient methane reduction, without detriment to the digestive efficiency and loss of productivity.

Parasite infestation is an enormous problem that incurs substantial losses in animal lives and productivity on the farms year after year (Sackett 2006, 2019; Piedrafita, 2010; McRae, 2015). Previous research indicated that parasitic infestation can decrease animal productivity, lengthen time until maturity with the resulting increase in methane output per longer life cycle of each individual animal. The parasitism might change the microbiome of the rumen shifting it into more methanogenic producing organisms. The correlation between methane emission and parasite sickness has important implication for individual farm economic losses as well as for agricultural contribution to climate change as a whole.

We decided to look at parasite infestation and intestinal microbiota as an indicator of animal overall health and to correlate it with seaweed supplementation at different levels of inclusion and with methane emission.

Parasite control remains a challenge for organic pasture raised sheep and goats that relies on natural substances (herbs, nutritional supplements, minerals, homeopathic preparation) and skillful pasture management. There is a need for new and innovative solutions for integrative parasite management and control that are natural, efficient and non toxic to the animals, do not pollute the environment and do not promote antibiotic and anti parasite drug resistance that is also harmful to human population.

Asparagopsis taxiformis is a red seaweed that contains large number of different biologically active substances including iodine and bromine halogenated metabolites, total phenolic compounds, flavonoids, chlorophyll, carotenoids, plant sterols, ketones, acetates.(Nunez,2018). They were found to have antibacterial, antiviral, antiprotozoal, antifungal, antioxidant, antiproliferative qualities in human and animal studies.(Paul,2006.,Pinteus,2015).

Total phenolic compounds are present as a major molecular group, with an important action in defending against bacteria, wounding and contributing to the antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity in the tissues. The pungent aroma of these algae is due to essential oil composed mainly of bromoform with smaller amounts of other bromine, chlorine, and iodine containing methane, ethane, ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetones, 2-acetohydroxypropanes,propenes,epoxypropanes,acroleins and butenons.(El-Baroty,2007).

The pronounced antibacterial activity against pathogenic shellfish and fish bacteria relevant to aquaculture - Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio Parahaemoliticus was demonstrated in vitro.(Genovese,2012).

A.taxiformis extract produced Quorum Sensing inhibition of bacterial biofilm.(Jha,2013).

The extract of A.taxiformis was active against multiple pathogens of sea bass including Photobacterium damselae, Vibrio harveyi considered to be resistant to most antibiotics in an aquaculture when fed by pellets.(Marino,2016)

A.taxiformis aqueous extract was effective inhibiting embryonic development of Neobenedenia ectoparasite of infected farmed barramundi fish, reducing hatching success of the parasite to 3% compared to with 99% for the seawater control.(Hutson,2012)

Algal extract has powerful effect on Leishmania infantum achieving 100% mortality of the parasite, and the LD 50 value was 25 mcg/ml for promastigote and 9 mcg/ml for amastigote.(Vitale,2015)

Asparagopsis taxiformis also contains water soluble polysaccharide carrageenan that is a digestion resistant fiber that was shown to have prebiotic properties and ability to selectively modulate intestinal microflora with survival of most favorable for the host microorganisms and suppression of the pathogenic microflora. There is an important interaction between bacterial microflora and parasite organisms in the intestine of the vertebrate animals. Alteration of the microflora with the prebiotics and other biologically active substances can make intestine less hospitable to parasites. Favorable microbiota can affect mucus synthesis that can increase expulsion of the parasite, reduce the permeability of mucus barrier that can better resist parasite infestation, secrete molecules that inhibit invading parasites, can prime protective immune response by stimulating host immune T reg cells in the gut.

Our study is done on organic farm and results would need to be confirmed in a different production systems.

There is a rising consumer demand for high quality meat products originating from the environmentally safe and ecologically sound agricultural sources. Organic livestock management became a popular alternative to conventionally raised animals. Organic is a labeling term that indicates that the food or other agricultural product has been produced through USDA approved methods.

These methods integrate cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity.

Organic livestock must be produced without genetic engineering, ionizing radiation, or sewage sludge managed in a manner that conserves natural resources and biodiversity, raised per the National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances (National List),Overseen by a USDA National Organic Program authorized certifying agent, fed 100 percent certified organic feed, managed without antibiotics, added growth hormones, mammalian or avian byproducts, or other prohibited feed ingredients (e.g., urea, manure, or arsenic compounds).

Organic ruminant livestock— such as cattle, sheep, and goats — must have free access to certified organic pasture for the entire grazing season. This period is specific to the farm’s geographic climate, but must be at least 120 days. Due to weather, season, or climate, the grazing season may or may not be continuous. Organic ruminants’ diets must contain at least 30 percent dry matter (on average) from certified organic pasture. The rest of its diet must also be certified organic, including hay, grain, and other agricultural products.

In contrast the USDA Grass Fed Program for Small and Very Small (SVS) Producers was designed to create opportunities for small-scale livestock producers who would like to have their ruminant animals certified as grass fed. This program requires that ruminant animals be fed only grass and forage, with the exception of milk consumed prior to weaning. Animals certified under this program cannot be fed grain or grain by-products and must have continuous access to pasture during the growing season. The diet shall be derived solely from forages consisting of grass (annual and perennial), forbes (e.g. legumes, Brassicas), browse, or cereal grain crops as Grain (corn, soybean, and small grain) plants that are allowed to be grazed and/or harvested and fed provided that the crop is grazed and/or harvested in the vegetative state (corn in a pre tassel stage, soybeans prior to bloom; small and cereal grains pre - boot stage).

The livestock producers can choose to become certified in both animal management systems or in only one.

Our farm follows both production methods at the same time. All farm animals including 48 sheep that participated in the research trial were certified organic and certified grass fed meaning that they were grazing only on a pasture derived forages, never have been fed grains or grain products, and never received antibiotics, hormones, chemical dewormers or other prohibited substances.

Z Farms is a certified organic farm in the village of Dover Plains, New York. It conducts certified organic poultry and meat operations and grows berries and vegetables.

The goal is to deliver the freshest possible certified organic and grass fed beef, lamb, goat’s meat, poultry, eggs and also berries and vegetables with the highest nutritional values to local communities. In order to do it we farm responsibly and carefully with the full respect to Earth natural resources and environmental factors.We have our own bees that help pollinate berries and orchard trees. Agriculture that is productive yet replenishing and balancing to the health of the soil and local ecology as a whole is our highest priority.

Crop rotations, cover crops, strip tilling, contour tilling, summer fallow, composting, integrative pest management, biological pest control are just a few examples of our responsible farming practices.

The goal is the development of fully sustainable diversified farm operations serving local communities and supplying customers with the best quality fresh meat, poultry, eggs, vegetables, fruits and berries. Our mission: utilization of sound farming and land practices in order to increase soil fertility, increase soil organic matter, build topsoil, minimize fossil fuel usage, emphasize environmental stewardship. Animal nutrition is an important component of establishing healthy ecosystem with the human population on its other end.

We have been in operation since 2015. The farm has total 210 acres, 60 acres are actively farmed and 70 acres are a protected woods and watersheds. We have two full time employees, and three part-time workers. We sell direct to consumers at the farmers markets, at the farm stand at the farm and also have been running the CSA for vegetables.

Cooperators

Research

To gather the necessary data, we have conducted a six-week field trial aimed at determining the impact of additional seaweed feed on sheep methane production, microbiome and health parameters(weight gain, body score , FAMACHA score, fecal egg count as an estimate of parasite infestation). Experiment was designed to evaluate results among 3 groups of 16 randomly assigned 18 months old Whiteface sheep.

Originally we planned to give 0.5% and 2% DME but at the beginning of the project decided to decrease the dosage. The reason was possible constraint in the production by Symbrosia of the seaweed powder at that moment. In order to secure a sufficient amount of the seaweed for the duration of the project, we reduced the amount we would use. So the animals actually were given 0.25% and 1% for low and high supplementation groups respectively.

We used FAMACHA score and fecal egg count to evaluate parasite infestation of the treatment groups sheep and compared them with the control. FAMACHA is a clinical score of the level blood sucking parasites infestation correlating anemia of the animal with the paleness of its lower lid mucous membrane (Gauly, 2004).

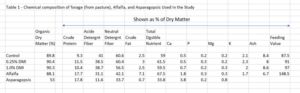

First group – Control - served as a baseline and was not given any seaweed.

Second group was given seaweed supplement equal to 0.25% of daily dry matter intake. Group 3 received higher dose equal to 1% of DMI. The calculated amount of seaweed was administered in feeding troughs and mixed with 20g of alfalfa per sheep for enticement every day at 7 am. The research assistant was present during the seaweed intake at all times and was directly observing that all sheep had an equal access to the trough. It took 15 minutes on average for the sheep to finish the supplement. There was no residual seaweed left in the trough in the end of the intake period on any day. Levels were based on assumption that a typical sheep consumes roughly 2% of its body weight on daily basis. Consequently, 0.25% DMI group was given 5 g/day of seaweed, while 1% DMI group was given 20 g/day. We also conducted nutritional forage, alfalfa, and Asparagopsis taxiformis powder(by Symbrosia) analysis for each of the groups (see Table 1). There was no significant difference in the nutritional composition of forage and supplements among the groups.

Sheep were provided run - in sheds for shelter, fresh water, salt and mineral supplements.

All sheep were located at the most southern field of organic farm located in Dover Plains, NY which has a total of 28 acres of the perimeter fenced area for the duration of the experiment.

The forage of the field consisted of mixed perennial grasses - Smooth Bromegrass, Orchardgrass, Perennial Ryegrass (90%) and White Clover(10%)

Each area of the field was grazed only once. Three groups of sheep were grazing separate fenced grass paddocks and there was no communication or contact between animals of 3 groups for the duration of the study.

The average temperature was 22 degrees C for June 2020, 25 degrees C for July 2020. The average humidity was 55% for June and 62% for July.

All methane measurements were done at the same time of the day at 7 am on each day of testing.

The sheep were Whiteface dry ewes 18( + - 2 months) months old and had previously one single pregnancy. All animals were certified organic and certified grass fed by USDA and were the property of our organic farm located in Dover Plains, New York where the experiment took place. They were the part of a larger 80 head herd of sheep.

The Dry Matter Content of the pasture was determined twice at the beginning and at the end of the experiment. The 0.25 sq2 meter quadrat area was used to shear all grass in 10 different areas of the fields and an averaged sample was collected. It was dried in the oven for 24 hours at 60 degrees Celsius. The weight of the dry sample was measured. Dry matter content on the first day of the project 6/08/2020 was 2405 lbs/acre at the control group grass paddock, 2420 lbs/acre at 0.25% supplementation group sheep grass paddock, and 2529 lbs/acre at 1% supplementation group grass paddock determined on the day before the sheep started their first rotation on the allocated swards.

On the day when sheep started their last rotation before the end of the project, on 7/15/2020 dry matter was 2710 lbs/acre on the sward allocated to control group, 2736 lbs/acre on the sward allocated to the low supplementation group , and 2775 lbs/acre on the sward allocated to the high supplementation group.

In addition, the rising plate method was applied in the field to measure the height of the grass and to determine the available dry matter of the sward on the first day of each rotation. The height of the grass was measured in 20 locations of each of the 3 grass paddocks designated for 3 groups of experimental sheep in the W type pattern. The amount of dry matter was calculated to the lowest level of grazing of 5 cm. The area of each field necessary to provide feed for each group of 15 sheep for 5 days was determined and fenced using temporary electric fencing. Each sward had a run in shed, mineral feeder, supplements trough and water tank with the fresh water ad libitum. Sheep were allowed to graze until the grass level of 5 cm and after that they were transferred to the fresh paddock where the rising plate dry matter determination method was repeated and an electric fence surrounding a new area of the field was assembled. Each group of experimental sheep completed 9 rotations during the experiment from 6/01/2020 to 7/21/2020 with each rotation lasting approximately 5 days.

Baseline and Testing Chronology

The pre - trial was started on June 1st, 2020. At that time all sheep were located on Northern field of the farm that was previously grazed several times on that season. They were divided in 3 similar size groups by simple randomization. At this point, we collected fecal parasite samples which served as a pre - trial baseline which was designed to help to confirm that all three randomly selected experimental group had approximately similar level of the infestation and confirmed the validity of the randomization. Fecal samples were collected rectally using the sterile lubricated glove. Fecal samples (around 10 grams of fresh feces) were inserted into the sterile plastic containers, and delivered immediately to the Cornell University Animal Health Diagnostic Center for fecal egg count analyses. After the sampling was finished, three group of sheep according to initial randomization were released on the three separate grass paddocks on Southern field of the farm and started their first rotation. It was a fresh pasture and was not grazed by any livestock animals for the previous 12 months.

We received the results of the original fecal egg count on June 6th. It confirmed that 3 randomized groups were approximately equally infected with the intestinal parasites.

One week later, on June 8th we did a first methane measurement and took a second sample of fecal matter for parasite analyses. After that we began to administer Asparagopsis feed supplement on a daily basis. We took two more methane measurement and two more fecal samples from each sheep three(June 29th) and six weeks( July 20th) thereafter – on June 29th and July 21st.

On each day of methane measurement and fecal sampling, all animals had body scoring and FAMACHA scoring done by the independent observer.

Fecal sample from each animal was tested initially by a fecal flotation test (FLOAT). The methodology employed was a modified protocol of the Wisconsin double centrifugation flotation test as described previously (Ref-1). A flotation solution with sugar 1.33 specific gravity was used. Parasites were examined microscopically and identified morphologically. The eggs of common gastrointestinal nematodes (Haemonchus sp., Cooperia sp., Trichostrongylus sp., etc.) are morphologically indistinguishable and are therefore identified as ‘Strongyle’ eggs. The eggs of Strongyloides sp. are distinct and are easily identified. The protozoans in the genus Eimeria were reported as Eimeria spp., as we have not attempted to differentiate their oocysts morphologically. FLOAT allowed us to quantify parasite stages and report as eggs/oocysts present per gram of fecal sample.

Sheep that had ≥100 eggs per gram of feces were further subjected to ‘Haemonchus Egg Test’(HEGG) and ‘Nematode Larval Culture’ (NLC). HEGG uses a peanut agglutinin stain that specifically binds to Haemonchus eggs and fluoresce thereby readily differentiated from other Strongyle type eggs (Ref-2). NLC is a 14-day procedure that allows nematode eggs in the order Strongylida to develop into third stage larvae which can then be morphologically identified to genus, and sometimes to species (Ref-3, Ref-1). The tail of sheath (anus to tip of sheath) and extension of sheath (tip of larva to tip of sheath) were the key features used to differentiate the third-stage larva to species. Other special morphologic features that helped identification of third-stage larvae include 1) kinked sheath at the tail tip for Haemonchus, 2) Pair of conspicuous oval bodies at the cephalic end for Cooperia, 3) 24-32 rectangular intestinal cells for Chabertia, and 4) truncated caudal extremity for Strongyloides.

At the same time as we collected samples for parasites, we also took sufficient fecal matter to do microbiome testing. 1 g of freshly rectally collected fecal matter was inserted into specialty vials, stored on dry ice(minus 80), and shipped via same-day delivery (on dry ice) to Weill Cornell Medicine Microbiome Core Lab. We have provided the lab with the set of bacteria and organisms that we wanted to assess as part of the study. These included Archaea, a methanogenic microorganism, as well as variety of bacteria that are deemed important for digestion and healthy microbiome composition.

DNA Extraction

Fecal pellets were deposited into Qiagen PowerBead glass 0.1 mm tubes (13118-50). Using a Promega Maxwell RSC PureFood GMO and Authentication Kit (AS1600), 1mL of CTAB buffer & 20μl of RNase A Solution was added to each PowerBead tube containing a sample. The sample/buffer was mixed for 10 seconds on a Vortex Genie2 and then incubated at 95°C for 5 minutes on an Eppendorf ThermoMixer F2.0, shaking at 1500 rpm. The tube was removed and clipped to a horizontal microtube attachment on a Vortex Genie2 (SI-H524) and vortexed at high-speed for 20 minutes. The sample was removed from the Vortex and centrifuged on an Eppendorf Centrifuge 5430R at 40*C, 12700 rpm for 10 minutes. Upon completion, the sample was centrifuged again for an additional 10 minutes to eliminate foam. The sample tube cap was removed, and the sample checked for foam and particulates. If foam or particulates were found in the sample, they were carefully removed using a P1000 pipette. The opened tube was then added to a Promega MaxPrep Liquid Handler tube rack. The Liquid Handler instrument was loaded with proteinase K tubes, lysis buffer, elution buffer, 1000mL tips, 50mL tips, 96-sample deep-well plate, and Promega Maxwell RSC 48 plunger tips. The Promega MaxPrep Liquid Handler instrument was programmed to use 300μl of sample and transfer all sample lysate into Promega Maxwell RSC 48 extraction cartridge for DNA extraction. Upon completion, the extraction cartridge was loaded into Promega Maxwell RSC 48 for DNA extraction and elution. DNA was eluted in 100μl and transferred to a standard 96-well plate. DNA was quantified using Quant-iT dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay Kit using Promega GloMax plate reader on a microplate (655087).

Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing Library Generation

Library generation follows the Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit Reference Guide:

https://support.illumina.com/content/dam/illumina-support/documents/documentation/chemistry_documentation/samplepreps_nextera/nextera-xt/nextera-xt-library-prep-reference-guide-15031942-05.pdf

Library Verification, Quality Check, Pooling

DNA sequencing libraries were washed using Beckman Coulter AMPure XP magnetic beads. Library quality and size verification was performed using a PerkinElmer LabChip GXII instrument with DNA 1K Reagent Kit (CLS760673). Library concentrations were quantified using Quant-iT dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay Kit using Promega GloMax plate reader on a microplate (655087). Library molarity was calculated based on library peak size and concentration. Libraries were normalized to 2nM using the PerkinElmer Zephyr G3 NGS Workstation (133750) and pooled together using the same volume across all normalized libraries into a 1.5ml Eppendorf DNA tube (022431021).

Sequencing

Pooled libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq instrument by Novogene.

Data Processing

Quality-based filtering and removal of host (Ovis aries genome, genome assembly Oar_rambouillet_v1.0, NCBI accession number GCF_002742125.1) sequences was performed using kneadData (https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/kneaddata/). Taxonomic abundance down to the species level was calculated using MetaPhlAn2 (Segata et al. 2012). Further analysis and visualization of the shotgun metagenomics data was performed using R scripts (R Core Team, 2014).

Methane Testing

Methane testing was done at the start of the trial (June 8th), then at 3 week and 6-week point. In order to do methane testing we built a small enclosure at the field. Enclosure was designed to minimize air movement while the sheep is being tested, and allow for air clearing between tests (See Exhibit 1 Photo ).

Each sheep was brought into an enclosure for a 3-minute test in the morning at 7 am on June 8th, June 29th and July 20th.

Testing was done using Laser Methane, Bluetooth-enabled mini-BE instrument (model # SA3C32A – BE) provided by Pergam Technical Services. Device was linked to Android pad, which was used to store measurement information using a dedicated application from the manufacturer. Settings on the device permitted parsing of the measurement data into 20 sec increments, which was averaged within and across those time segments. This mitigated impact of occasional ultra-short spikes in methane, while capturing prolonged emissions. For each sheep we tabulated peak(eructation) emissions (defined as average over highest 20 sec interval), as well as average(respiration) over the entire 3min period. Results could have some variability in the event the 3min period does not cover a burp or other methane emission. However, we found high consistency in seeing a distinct peak for each of the measurements, which suggested to us presence of an eructation event. Overall use of LMD (laser methane detection) methodology has been well investigated in research and found to have high correlation to other methane measurement techniques.

Health Monitoring

Finally, we collected several basic measurements that covered weight, body score, and FAMACHA score of each sheep on June 8th, June 29th and July 20th. These data were mostly used to determine existence of any spurious correlation and to monitor health of the animal (make sure they are gaining weight throughout the study). (See Exhibit 5 Photo)

Statistical Analyses

We have calculated several descriptive statistics for methane, parasite count, and microbiome. In all cases we found that data were highly right skewed and did not feel assumption of normal distribution could be justified. Hence, we looked at a choice of non-parametric test. We selected Wilcoxon signed- rank test to evaluate significance in the change among matched samples. Specifically, whether we could reject the hypothesis that samples came from populations with the same distribution. To calculate relevant statistics we used Excel, as well as an online program provided by Vassar - http://vassarstats.net/wilcoxon.html. Since data was already in Excel, we ran several ANOVA tests and multiple regressions assuming normal distribution, which yielded directionally similar conclusions, but was not included in this report.

This section presents results of our study. Presented analyses are divided into four parts: 1. Weight characteristics, 2. Methane testing, 3. Parasite testing, and 4. Microbiome analyses.

Weight characteristics.

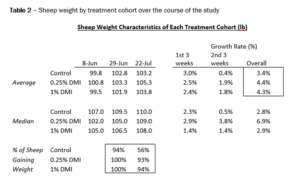

At the start of the trial, there was little difference in average weight of the three cohorts (see Table 2). We view weight gains as an indicator of sheep overall health, as well a critical variable for commercial viability. A supplement that reduces methane at a cost of lower average daily weight gain would not be practical. We were pleasantly surprised to see that average daily gains by groups that were given seaweed were roughly 1% higher, which is a very positive result. Even more reassuring is the difference in the number of sheep gaining weight. As shown at the bottom of the table, Control group had only 56% of the sheep gaining weight, while treatment group had almost 93% experiencing weight gains during the second half of the study. On the surface, this would be supportive of anti-parasitic properties of seaweed that we discuss later in this section. We are comfortable concluding that use of this supplement has no adverse impact on animal productivity and is likely to be beneficial.

Table 2 – Sheep weight by treatment cohort over the course of the study

Sheep Weight Characteristics of Each Treatment Cohort (lb)

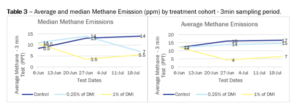

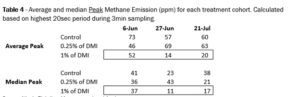

Average and median methane emission results for each of the treatment cohorts are shown Table 3, while Table 4 shows average and median for the peak observations. We are encouraged to see relatively similar baseline of methane emissions at the beginning of the study. Furthermore, values that we observed are within range calculated in other studies.

Table 3 – Average and median Methane Emission (ppm) by treatment cohort - 3 min sampling period.

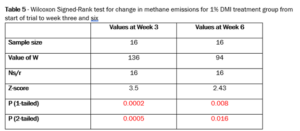

Casual examination of average and peak trends suggests a similar behavior. For example, high treatment group (1% DMI) exhibits clear improvement over time, which is evident in both average and median values. Relative to the baseline starting point, improvement at the three-week point is a remarkable 65%, and somewhat lower 50% at the six-week point. Modest increase from week 3 to week 6 is surprising, but there are possible explanations tied to changes in pasture intake and/or some decrease of effectiveness of methane reducing efficiency of the seaweed. We discuss these possibilities later in the report. We validated our finding using Wilcoxon Signed-rank Test, which showed a high degree of significance at both week 3 and week 6. Statistics are shown in Table 5 below.

Table 5 - Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test for change in methane emissions for 1% DMI treatment group from start of trial to week three and six

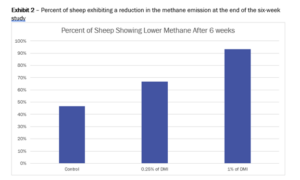

Neither control group nor 0.25% DMI group exhibited statistically significant decline in methane emissions. Lack of statistically significant decline for low-dose cohort is surprising and somewhat contradictory to prior studies. This requires a closer look at the underlying data. The most salient characteristic is the difference between average and median values at the end of the study (See Table 2). While average emissions rose by 21%, median declined by 36%, which suggests presence of significant outliers. When we simply examine number of sheep showing improvement in methane expulsion, there is a positive trend (see Exhibit 2).

However, average values for the 0.25% cohort did not improve due to 4 sheep that showed a significant rise in the level of emissions. Given the small sample size any attempt to “exclude the outliers” seems inappropriate. However, we note that all 4 sheep had one common characteristic – significantly higher parasite levels at the beginning of the study. This was evident in both average egg count, as well as growth in culture (i.e. Nematode larval culture hatching success rate). Strongyles parasite concentration was 2x the average of the group. Link between methane and parasites would explain the findings. It has been considered in research and will be discussed later in the report.

Exhibit 2 – Percent of sheep exhibiting a reduction in the methane emission at the end of the six-week study

Parasite testing

We collected data on several different parasites found in the fecal matter of the sheep. We identified three that existed in sufficient amount to warrant more detailed investigation – Eimeria, Strongyles, and Strongyloides Papillosus. Tabulation of data suggested relatively low, and infrequent occurrence of Strongyloids. Levels were not deemed high enough to significantly affect health of the animal.

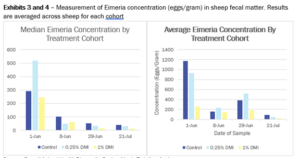

Looking at average (see Exhibit 3) and median (see Exhibit 4) concentration of Eimeria we note a couple of striking trends.

First is the remarkable decline between June 1 and June 8, which is the first week sheep were moved animals from the Northern pasture where they were rotated several times on the same grass paddocks during 2020 spring season with the higher stocking rate to the Southern pasture(the place where experiment took place) which was not grazed for the previous 12 months and had much lower stocking rate. It was a week of the pre-trial and the seaweed supplement was not started until June 8th. The significant decline of the sheep fecal egg counts occurring after the transition from highly grazed pasture with the higher stocking rate to non contaminated non grazed during that season pasture confirms previous observation about the importance of timely rotations and appropriate stocking rate for the integrative worm control.

Declines in parasite concentration continued through the study. However, big difference between average and median values suggests a need for a non-parametric statistical test. We conducted the tests over every periods. Results for parasite reduction were highly significant for the first week across all groups.

Exhibits 3 and 4 – Measurement of Eimeria concentration (eggs/gram) in sheep fecal matter. Results are averaged across sheep for each cohort

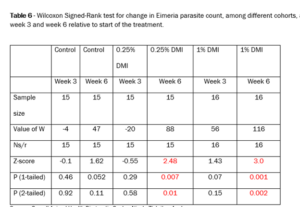

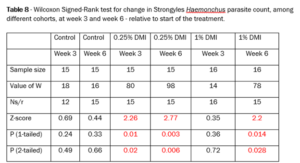

However, when examined over the period to treatment (June 9th to July 21st), differences emerge (see Table 6).

None of the cohorts showed improvements at a three-week mark. Though 1% DMI cohort came close. By week six stark differences emerge. Both cohorts that were given seaweed supplements had statistically significant reduction in Eimeria parasite loading, while control group improved (due to transition to the uncontaminated pasture), but failed statistical significance.

Table 6 - Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test for change in Eimeria parasite count, among different cohorts, at week 3 and week 6 relative to start of the treatment.

We next turned to examination of Strongyles. Given its prevalence among sheep and strong adverse impact on their health and survival, we took a deeper look by examining both initial egg count and larval count of barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus), as well as presence of Cooperia spp.

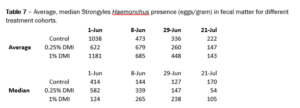

Qualitatively, trends in Strongyles concentration mimic those of Eimeria (see Table 7). We generally see a sharp drop once the animals are moved from Northern field to Southern field on June 1. This is followed by mostly steady decline in all groups. Next, we performed statistical analyses, similar with the one used in assessing Eimeria trends (see Table 8).

Table 7 – Average, median Strongyles Haemonchus presence (eggs/gram) in fecal matter for different treatment cohorts.

Just as was the case with Eimeria, we note statistically significant decline in Strongyles concentration by week 6 in both treatment groups, but no improvement in the control group. However, effect seems to be higher for 0.25% DMI cohort in magnitude, and its presence was statistically significant at an earlier, 3 - week milestone.

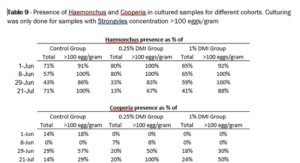

Up to this point we focused solely on presence of parasite eggs in the fecal matter. However, we also asked the lab to look at the Nematode larval culture success rate, which is of great importance when assessing health of the sheep since it estimates actual viable parasite in the feces as opposed to possible dead eggs in the stool. Culturing was done only for the samples that had higher than 100 eggs/gram concentration of Strongyles (Haemonchus contortus) eggs. Culturing below that level was not deemed useful due to minor impact on overall health. Similarly, we examined emergence of Cooperia species. The rise of Cooperia sp. counts in reverse to decline of Haemonchus sp. is thought to indicate favorable rebalancing of gut organisms with the shift to less harmful, and possibly, commensal varieties.

Table 9 highlights significant decline in Haemonchus contortus as treatment continued. In other words, not only are we seeing declines in the egg counts, but fewer of them hatched. Interestingly, the decline in Haemonchus was particularly notable for the lower 0.25% dose group. This is consistent with earlier observation that 0.25% DMI group had earlier and more significant decline in the Strongyles egg count. Similarly, we are seeing a favorable rise in Cooperia. This is a very encouraging finding, which suggests that use of Asparagopsis as a feed supplement has not resulted in higher parasite loads. In fact, we saw a significant decline in both egg count and hatching propensity. As far as we know, this is the first time such observation has been published.

Table 9 - Presence of Haemonchus and Cooperia in cultured samples for different cohorts. Culturing was only done for samples with Strongyles concentration >100 eggs/gram

There was no difference in the body scoring and FAMACHA scoring between animals of three experimental groups.

Microbiome analyses

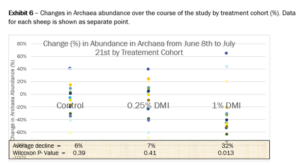

We analyzed variety of gut bacteria and microorganisms, using Illumina Shotgun sequencing, that were captured in the fecal matter. Our goal was to assess the impact of seaweed supplement on methanogenic organisms (Archaea), as well as see if there is a change in other bacteria. Examining abundance of the Archaea (see Exhibit 6) corroborates with the results of our methane expulsion test. We note a significant decline in the abundance of methanogenic archaea for 1% DMI group, but much more limited impact for control group and 0.25% DMI dosing. Results for the high dose group were statistically significant at 1% level, using Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Exhibit 6 – Changes in Archaea abundance over the course of the study by treatment cohort (%). Data for each sheep is shown as separate point.

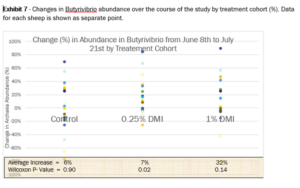

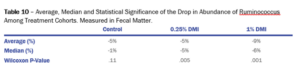

We were encouraged to see a statistically significant rise in Butyrivibrio, which is a beneficial gut bacteria, for 0.25% DMI group (see Exhibit 7). Result was directionally similar for higher dose group but did not meet statistical hurdle. There was also statistically significant drop in Ruminococcus for groups supplemented with 1% of Asparagopsis (see table 10).

This confirms one potential pathway for efficacy of the seaweed, as we discuss in the next section. We note a statistically significant drop in Peptostreptococcaceae bacteria for 1% DMI cohort, while drop for other groups was not statistically significant.

Exhibit 7 - Changes in Butyrivibrio abundance over the course of the study by treatment cohort (%). Data for each sheep is shown as separate point.

Table 10 – Average, Median and Statistical Significance of the Drop in Abundance of Ruminococcus Among Treatment Cohorts. Measured in Fecal Matter.

DISCUSSION

Methane Reduction

Our results demonstrated significant 60% methane reduction in the exhaled air for pasture-raised organic sheep given red seaweed as a feed supplement at 1% DMI after 3 weeks, and 50% methane reduction after 6 weeks. Mild increase in methane expulsion from 3 weeks to 6 weeks period may be related to somewhat different pasture dry matter intake and composition (mixed grasses, brome grass, clover). Sheep were rotated every 5 days on a fresh green paddock as part of grass-fed operation. Another possibility is that mild increase in average methane production was related to microbial adaptation of the rumen methanogens under selective pressure of red algae, and survival of more anti-methanogen resistant species.

Similar decrement in methane reduction of anti-methanogenic compounds secondary to microbial adaptation was described during administration of synthetic, chemical bromoform to different livestock animals. This rapid decrease in methane reducing efficiency in conjunction with the high toxicity precluded use of those compounds on a larger scale in the past (Denman, 2007, Abecia, 2012, Knight, 2011). However, increased resistance to methane reducing effect was not observed for red seaweed algae in the past. Longer than 6 weeks trials are necessary to evaluate this possibility.

Respiration chambers are used to measure CH4 at an individual animal level. Use of chambers is technically demanding, and only a few animals can be monitored at any one time (McGinn et al. 2008). However, these systems provide continuous and accurate data on air composition over an extended period of time. Laser methane detector gave us an opportunity for non-invasive and non-contact scan sampling of enteric CH4. With the possibility for real-time CH4 measurements, the LMD offers a molecular-sensitive technique for enteric CH4 detection in ruminants. Initial studies have demonstrated a relatively strong agreement between CH4 measurements from the LMD with those recorded in the indirect open-circuit respiration calorimetric chamber (correlation coefficient, r = 0.8, P < 0.001). The LMD has also demonstrated a strong ability to detect periods of high-enteric CH4 concentration (sensitivity = 95%) and the ability to avoid misclassifying periods of low-enteric CH4 concentration (specificity = 79%). Being portable, the LMD enables spot sampling of methane in different locations and production systems (Chagunda, 2013).

Our results are in line with a few previously reported investigations of methane reducing properties of Asparagopsis taxiformis in ruminant animals that were done in vivo.

Xixi Li (2016) reported significant CH4 emission reduction by 50-80% over a 72-day feeding period with the pelleted grain/straw in Merico sheep supplemented by Asparagopsis taxiformis at approximately 2-3% DMI. There was no significant effect on methane emission at 0.5% DMI.

Breanna Roque (2019) administered Asparagopsis armata which is similar in its biochemical properties to Asparagopsis taxiformis to grain/forage fed lactating Holstein cows at 0.5% DMI and 1% DMI. The significant reduction of methane emission was found at both inclusion rates - 26% reduction in methane yield (adjusted for feed intake) at 0.5% DMI and 42% reduction in methane yield for 1% DMI.

Robert Kinley(2020) showed 40% and 90% decrease in methane emission in beef cattle fed high grain diet at 0.1% and 0.2%, as well as demonstrated weight gain improvement of 53% and 42% respectively.

In contrast to Kinley(2020), there was no pronounced methane reducing effect in the low 0.25% supplementation group in our trial. One possible explanation is that the sheep in current trial are exclusively fresh forage fed and raised only on natural pastures, without concentrates and grains added to their ration. Another explanation of the discrepancy in dosages of the seaweed for methane reduction in several previous trials are the difference in the active compound bromoform concentration Kinley(2020). It is possible that the seaweed with the higher bromoform concentration might exhibit methane inhibiting action in the rumen in the lower concentration.

It was shown previously that methane production depends on feed composition. More high fiber feed (fresh forage as opposed to concentrated grains) leads to formation of more H2 protons available for methane production as result of efficient hydrolysis of plant fibers by cellulolytic bacteria. Since the sheep in the present study are exclusively raised on forages, it is possible that they produce relatively more methane and need higher doses of anti-methanogenic compounds. Another possibility is that 0.25% DMI seaweed inclusion did not produce significant reduction in methane in sheep versus cows might be the genetic differences in rumen microbiology in different species, and even in between breeds within the same species.

It was shown that certain sheep breeds with the smaller rumen size have unique Sharpea-enriched microbiome characterized by lactic acid formation and utilization. It results in lower hydrogen production and lower methane formation (Kamke, 2016). It is possible that the Whiteface sheep investigated in this study have relatively larger, and genetically higher, methane producing rumen since animals were bred historically for larger body frames and carcasses for an efficient meat production.

There was a significant 1% higher weight gain per sheep in both treatment groups vs control. The sheep were rotated on the pastures for the duration of the experiment so the exact DMI of each individual sheep was not calculated. Based on significantly more weight gain in the supplemented groups, it is assumed that supplemented sheep had improvement in their metabolic parameters and rumen digestion efficiency. Sheep voluntarily consumed an allocated portion of the seaweed mixed with the 20g alfalfa per sheep in the feeding trough every day of the experiment. There was no observable detrimental effect on their behavior or appetite, as well as on body scores evaluation. It is in alignment with the previous investigations conducted in vitro that showed no detrimental effect of Asparagopsis inclusion in the diet at 2% or less of DMI on rumen fermentation efficiency and short chain fatty acids production (Li, 2016).

Microbiome and Potential Mechanism for Methane Reduction

Ruminant animals digest cellulose and lignin from the fibrous material of the pastures and convert them through Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) glycolytic pathway to the short chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate and butyrate) with the help of cellulolytic and amylolytic bacteria in the rumen. The SHFA (short chain fatty acids) are absorbed in the circulation from the ruminal wall and are used for energy production, growth and all aspects of metabolism. The common end results of fiber degradation in the rumen are acetate, propionate, butyrate, and less significantly lactate, formate, and H2 - hydrogen. If hydrogen accumulates significantly it can decrease rumen pH and inhibit all enzymatic activity with the resultant loss of all energy efficiency and metabolism. The common acceptor and neutralizer of elevated Hydrogen in the rumen are methanogenic microorganisms from the group of archaea that serve as a so-called “hydrogen sink”. They absorb extra hydrogen and combine it with CO2 to produce CH4 methane that is burped by the animal. Red seaweed works by inhibiting and reducing numbers of methane producing bacteria or archaea, decreasing available “hydrogen sink “and shifting microbial fermentation into more efficient biochemical pathways. The short fatty acid ratio is significantly changed by the supplementation with Asparagopsis taxiformis both in vivo and vitro. The production of acetate is decreased, the acetate/propionate ratio is decreased, propionate production is increased after feeding red seaweed. Acetate and butyrate are known to be Hydrogen donors, and propionate serves as hydrogen acceptor in the ruminal glycolytic pathways. The propionate becomes a hydrogen sink instead of methane synthesized by archaea. It leads to a more efficient nutrient utilization, more SCFA production per kg of dry matter and better animal health, since useful fatty acids are synthesized and utilized by the animal using hydrogen molecule instead of horizontal hydrogen transfer to the methanogens that leads to loss of the useful nutrient through the methane emission. Total volume of SCFA produced in the rumen is not decreased by Asparagopsis taxiformis supplementation in smaller doses( less than 2% of DMI). In a higher amount of supplementation, the SCFA volume gradually declines, which might signify decrease in the animal production and health.

Higher than 5% DMI of supplementation decreases Organic matter digestibility, as well as SCFA synthesis, and precludes its application for agricultural animals, despite total 100% methane emission inhibition (Kinley, 2016). Our study shows that 1% of DMI is the optimal methane reducing dose for organic fresh forage raised sheep without additional grains or concentrate in their diet. It provided also improved weight gain and did not worsen body scores. In this way methane reducing strategies accomplish two goals at the same time. One is to reduce methane emission by the animals helping the global ecology, and second - to shift animal metabolism into a more efficient and productive pathway.

The IIlumina shotgun microbiome analysis revealed a significant decrease of Archaea population as well as archaea/bacteria ratio in the feces in both treatment groups compared to control at all treatment points, but only high supplementation group change reached statistical significance. The reduction of Archaea was directly proportional to the reduction of methane emission by the seaweed in the 1% DMI group. It is in alignment with the previous research by Breanna Roque (2019) that showed the average relative abundance of Euryarchaeota (archaea) over the duration of the experiment was lower in A.taxiformis group compared to control (1.38% and 1.79% respectively). Archaea are methane producing organisms of the rumen and their total content is 3-4% of the total microbial population. They efficiently remove excess hydrogen from the rumen and convert it to methane using the cobamide-dependent methyltransferase step in the synthesis of the CH4. A.taxiformis contains biologically active secondary metabolite bromoform and dibromochloromethane that can react with reduced vitamin B12, and in this way can inhibit critical last step in methane synthesis (Martinez-Fernandez, 2016).

The fecal samples that we collected were analyzed for microbiome abundance and composition in the present study. In the previous research of Andrade, 2020, it was shown that there is co-occurrence of Amplicon Sequence Variants of archaea in rumen and fecal microbiome, indicating that fecal Archaea microbiome can be used as a proxy for the ruminal Archaea population in the cattle. Based on those results, we make conclusions about possible rumen archaea physiology analyzing only fecal microbiome in the present study.

On the other hand, it is not firmly established that lower intestinal tract microbiota directly reflects rumen and stomach microbial physiology. There is previous research that shows that bacterial microbiota populates different compartments of the gastrointestinal tract independently and there might be no direct correlation in between the species in different parts (Wang, 2017, Tanca,2016). We assumed that there is some correlation between feces microbial composition and upper GI microbiome because of the linear physical nature of the digestive tract and its interconnectivity. Changes in one compartment would cause physiologic and immunologic changes in other areas of the GI tract. This approach obviously has limitations and awaits further confirmation.

Microbiome, Parasite Reduction Mechanism, and Link with Methane.

One of the most important indicators of sheep health and nutritional status is the ability to withstand parasite infestation. Hundreds of thousand sheep are lost every year due to an uncontrolled parasite sickness, incurring significant economic and financial losses (Mamun, 2020). Emerging parasite resistance against chemical dewormers in commercial operations is a growing problem. Organic pasture raised sheep are particularly vulnerable since they spend all their life cycle on fresh green pastures, which means much higher exposure to the environmental parasites. Chemical dewormers are not allowed in organic production, and operations rely on integrative parasites management including natural herbal compounds, mineral supplements, and particular types of rotational( adaptive multi paddock) grazing in order to reduce the parasite load.

There was no significant difference in FAMACHA scores among the groups.

There was a significant drop in the fecal egg counts in both treatment groups compared with the control. The most important, and deadly, parasite blood sucking nematode Haemonchus Contortus from Strongylos sp., decreased sharply in 0.25% DMI supplementation group. The Nematode larval culture success rate was significantly reduced in both treatments as a result of A.Taxiformis supplement. It means that not only fecal egg count declined, but infectious pathogen prevalence was diminished. Functional, active parasites from the feces that grew well in laboratory culture were also reduced (Hubert,1984). It signifies that A.taxiformis might have a substantial anti parasite activity against gastrointestinal nematodes.

Our results showing significant anti parasite activity against Haemonchus Contortus.

This is the most important pathogen affecting global sheep production. These are new finding and we have not found any indication that they have been explored in the past.

There is a growing body of evidence that reduction in greenhouse gas emission is associated with worm control in lambs. Kenyon et al., 2013 showed that clinically parasite infested sheep consistently took longer to reach market weight and generated extra 10% of CO2 per kg of weight gain over healthier non infested sheep, and a successful parasite control helped to reverse the trend. Houdjik et al., 2017 demonstrated that parasitism increased calculated global warming potential per kg of lamb weight by 16%, which was similar to the measured impact of parasitism on feed conversion ratio. Fox et al, 2018 showed that the ubiquitous parasite Telagosargia circumcincta drove a 33% increase in methane yield from the infected sheep.

The parasitism significantly increased methane output per kg of DMI, even though DMI was decreased in absolute numbers in sick animals. It signifies that gastrointestinal nematodes in ruminant animals can lead to substantial changes in digestive tract including increased cell turnover, changed permeability, changed PH, altered secretory activity and inhibited gastric acid production.

Parasite infestation has a significant effect on host resident microbial communities. It was shown that Haemonchus Contortus infestation is increasing abomasal PH, negatively affecting digestive function of the sheep, decreasing total amount SCFA produced in the rumen, decreasing DMI, causing diarrhea and weight loss (El-Ashram, 2017).

Illumina shotgun microbiome analysis of the feces revealed a significant decrease in the abundance of Ruminococcus species from Firmicutes phylum in both low and high supplementation treatment groups. If fecal Ruminococcus abundance is functionally independent and distinct from rumen microbiome, decrease of its the population after reduction of the parasitism in the rumen might signify the improvement of cellulolytic activity in the rumen with the resultant less fiber available in the large intestine (Andrade, 2020). It might explain the subsequent decrease of its abundance in both treatment groups at 3 and 6 weeks.

On the other hand, if the interdependence of ruminal and lower intestinal bacteria is assumed, the decrease of Ruminococcus abundance in the feces might directly correlate with rumen bacterial counts. Ruminococcus is one of the most important cellulolytic enzymes of the rumen, digesting fiber with the resultant formation of short chain fatty acids, predominantly acetate, formic acid, H2 and CO2 in the presence of methanogenic bacteria. In this way it can directly contribute to an increase in methane production in the rumen (Tapio, 2017).

When methanogenic archaea are absent, fermentation is shifted towards succinate and formate, as opposed to acetate and H2, and the amount of methane is significantly decreased (Latham,1977). Because there are less methanogenic archaea available to accept H2 in the rumen secondary to red seaweed inhibition, there might be a shift in the Ruminococcus fermentation spectrum to less acetate production that might possibly result in a decrease in the relative abundance of this species. Decrease of Ruminococcus species significantly correlated with the decrease in methane production in the high supplementation group. Alternatively, it is possible that as a result of the seaweed supplementation there is a shift to Fibrobacter species that have high cellulolytic activity but are not significant H2 producers and do not contribute to high methane production as opposed to Ruminococcus species.

Parasite upregulates host carbohydrates and cellulolytic enzymes synthesis as a part of adaptation to the environment and attempts to cause chronic infection where parasites can survive and thrive for a long time (Robert Li, 2015; Leung, 2018; Scotti, 2020). In an experimental infection of goats with Haemonchus Contortus, there was a significant shift in the microbiota with the upregulation of biochemical pathways responsible for carbohydrate, amino acid and lipid metabolism (Robert Li, 2015).

Since the A.taxiformis might have direct nematicidal effect on the parasite, decrease in parasite infestation might lead to less stimulation of the cellulose digesting microbes, with the resulting decrease in relative abundance of Ruminococcus and all Firmicute species in the rumen with the shift into lower Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and less resulting total methane production. The diminished drive to increase cellulolytic activity after the reduction of the parasite activity, might be synergistic in shift of microbiome to lower Firmicutes species and possibly more abundant Bacteroides and other non-cellulolytic bacteria (Peachey, 2019).

There is a complex interaction between parasite and host microbiota when parasites produce secretory products stimulating more cellulolytic activity of the Ruminococcus species and relative shift in SCFA for more acetate and H2 in the rumen for use to its own metabolic advantage. The result might be an overall increase in methane emissions. Conversely, red seaweed inhibition of both parasites and methanogens, brings methane production down and improves animal health (Peachey, 2019).

Our results showed a significant trend towards increase in Butyrivibrio species particularly in the low supplementation group at 6 weeks of the study. Butyrivibrio genera is a Clostridia species organism from the Firmicutes phylum that has an important physiologic activity in the rumen and all intestinal tract. It degrades the polysaccharides and ferments the released monosaccharides to yield short chain fatty acids that are used by the ruminants for production of meat, milk and fiber (Palevich, 2020). The important product of Butyrivibrio microbial metabolism in the rumen and in the intestine is butyrate that may account for up to 10% of daily SCFA production. It is considered to be an important energy source of ruminal and intestinal epithelium, as well as stimulator of the ruminal epithelium growth and function. Butyrate is also known to affect metabolic activity of the ruminal epithelium, abundance of transcripts of proteins mediating SCFA absorption, epithelial blood flow and rumen motility. It was also shown to exert a trophic and antiinflammatory effect on stomach and intestinal mucosa (Palevich, 2020).

When infused directly into rumen, butyrate increased efficiency of SCFA absorption from the rumen of the growing goats. In terms of growth performance, butyrate use increased daily weight gain in animals in many studies. Butyrate is a potent inhibitor of inflammation (Gorka, 2017). In a study of Haemonchus Contortus experimentally infected goats, there was a significant difference in Butyrivibrio abundance between uninfected control and H.Contortus infected goats (Robert Li, 2015). It is possible that an increase in relative abundance of Butyrivibrio in a low dose treatment group after 3 weeks and 6 weeks was related to epithelial repair and regeneration with the production of anti-inflammatory butyrate after A.taxiformis caused decrease in parasite infestation.

Asparagopsis taxiformis contains a significant amount of polysaccharide carrageenan as one of its biologically active compounds that contains galactose molecules as monomers combined by specific complex carbohydrates 1-4- bonds.(Nunez, 2017). It was shown to have prebiotic qualities in the previous studies.(Han, 2019). Since Butyrivibrio species are able to hydrolyze galactose bonds, red seaweed might serve as a prebiotic for the beneficial intestinal bacteria independent of its effect on ruminal bacteria.

There was a less significant increase in the abundance of the Butyrivibrio in the high treatment group. It is possible that at higher dose A.taxiformis exerted direct antimicrobial effect and inhibited the beneficial bacteria including Butyrivibrio species. The fact that we observed more significant anti parasite effect in low dose group than in high dose group might be a confirmation that the net effect is a sum of direct antiparasitic effect plus shift in the microbiota to more beneficial microbiome communities, that is supportive of hosts improved nutritional status. It is possible that at higher doses, the beneficial effect on the microbial communities is replaced by too strong antibacterial effect, that is less conducive to the parasite expelling and restoration of the normal flora.

This study highlights an area of emerging research on ecology and remediation of methane emission by ruminant livestock animals. The findings demonstrate that at 1% DMI red seaweed Asparagopsis taxiformis supplement reliably decreased methane emission(up 70% reduction) from organic grazing sheep but not at 0.25% DMI. There was an improvement in productivity and higher body weight gain in both high and low supplemented sheep compared to control.

The fecal microbiome analysis revealed significant reduction of methanogenic archaea in a sheep group supplemented with 1% DMI of red seaweed for 6 weeks.

Both supplemented sheep groups had a significant reduction in the abundance of the Ruminococcus species in the fecal microbiome compared to the control group.

Low supplementation sheep group demonstrated significant increase in the abundance of Butyrivibrio species after 3 weeks of supplementation compared to the high supplementation and to the control group.

Butyrivibrio spp are considered to be a beneficial gut bacteria that have a favorable effect on the intestinal health and performance.

There was no significant change of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios in both experimental groups.

Analysis of the sheep feces revealed a significant decline of several major parasite species in both high and low experimental groups after both 3 weeks and 6 weeks of the study.

Our results indicate that dietary supplementation of the Asparagopsis increased the abundance of the beneficial gut bacteria and reduced the parasite load in addition to its important methane reducing effect.

Widescale implementation of the Asparagopsis as a dietary supplement has the potential to make organic farming operations even more sustainable without substantially increasing cost.

It is important that methane reducing and anti parasitic effects are investigated in livestock animals in different production systems for valid results in future.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

1.Presented the abstract at the North East Integrative Pest Management conference on November,17,2020 and March,24 2022.

Video (1)

2.Two on-farm demonstrations occurred on October 10th, 2020 and October 24th 2021. Twelve customers of the farm were given a presentation and explanation with the printed handouts of the research project and its implication for climate mitigation efforts and health of the animals.

3.We conducted three farm tours for seven customers of the farm and for five farmers from Wingdale, NY and from Amenia, NY on November 14th, 2020, September 18th, 2021 and October 23rd, 2021. We showed the pastures, the sheep, the enclosure for measuring methane, and the trough where the seaweed powder was administered. We explained how we calculated the dosage of the supplement and how we secured that it was taken by the animals.

4. Forbes Magazine published an article about our research project: 11/21/2020

https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffkart/2020/11/21/hawaiian-seaweed-makes-cows-90-less-gassyand-thats-good-for-climate-change/?sh=4f5cb1545c4b :

"Symbrosia has already received funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to analyze the use of its seaweed feed supplement at Z Farms Organic in Dover Plains, New York. A pilot began there in June, testing the seaweed supplement on a commercial grazing system.

“All research prior had been in an academic feedlot or controlled dairy setting,” Akbay says. “Meanwhile, the majority of methane emissions in the beef or dairy supply chain come from the grazing cycle — digesting grass is more difficult than corn or soy.”

The seaweed was included as part of the mineral feed supplement provided to pasture-grazing animals.

“In practice, we found over 70% reduction of methane in 45 head of sheep. The 70% versus 90% reduction is dependent on product quality and highlights how far our team has come in growing and processing, and also the extra 20% improvements needed to replicate that 90% target reduction.”

Besides less methane, Z Farms owner Dr. Diane Zlotnikov has reportedly found overall health improvements in the eyes, coats, and skin of her sheep and hopes to use the supplement commercially in the future."

5. We submitted research paper in the Journal of Cleaner Production and are waiting for the response in regards to publication.

6. We participated in the video presentation about the project with Verge production company in February of 2021 that is now posted on YouTube for general viewing. In a video recording we presented the original concentration of Seaweed that we were planning to give. Last month we contacted the Verge company and asked them to change the seaweed supplement concentration to the one that was actually given in the study - 0.25% for the low supplementation group and 1% for the high supplementation group. The producer of the Verge company made correction in the closed captioning of the video.

Learning Outcomes

Integrative parasite control

Rotational grazing

Climate change mitigation tools and awareness

Project Outcomes

The project taught us the importance of intense rotational grazing and skillful pasture management for parasite control and prevention in organic sheep.

Originally we planned to give 0.5% and 2% DME but at the beginning of the project decided to decrease the dosage. The reason was possible constraint in the production by Symbrosia of the seaweed powder at that moment. In order to secure a sufficient amount of the seaweed for the duration of the project, we reduced the amount we would use. So the animals actually were given 0.25% and 1% for low and high supplementation groups respectively.

Also, originally we recruited 48 sheep and randomized them to three equal groups of 16 sheep. Two sheep were removed from the study and from the final analysis because of the predator related injury and sickness.

The project underscored the importance of the integrative parasite control when many different measures (rotational grazing, herbs, supplements, minerals, seaweed) help to improve animals health, prevent losses and increase profits. Four farmers from Wingdale, NY and Amenia, NY started to use brown seaweed for their livestock animals to improve productivity and reduce methane emissions since red seaweed supplement is not commercially available yet. In social media posts and in email communications they noticed improvement in animals health.

It helped to understand relationship between the small farm and the planetary ecosystem and livestock contribution to the global climate mitigation efforts.

The project taught us the importance of regenerative farming for atmospheric carbon sequestration and storage in the soil biomass. Methane emission reduction from the grazing animals can be complementary to carbon sequestration by the healthy soils on organic farms and can help to reduce climate footprint of the agricultural industry as a whole.

The study was well designed. It provided meaningful answer about the efficacy of the seaweed supplement for the methane reduction. It showed a significant decline of the relative abundance of the methanogenic archaea in the seaweed treatment groups. There was a significant trend for the increase of the genus Butyrivibrio member of Clostridia species in the intestinal microbiome of the seaweed treated groups that is considered to be a part of the beneficial flora.

The seaweed treated group demonstrated significant decrease in the parasite infestation by several major classes of the intestinal worms.

The timing of the switch of the animals from the Northern more contaminated field to the Southern not previously grazed field where experiment took place might not have been ideal for the demonstration of the parasite reducing effect of the red seaweed.

The transfer of the animals from the more contaminated previously several times grazed field into the fresh previously not grazed field during the pre trial resulted in a large drop in the parasite counts just from the rotation itself. It may have clouded the evidence of the anti parasite effect of the seaweed supplement. The anti parasite effect might have appeared much more robust if the study was conducted later in summer when the animals had been on the previously not grazed during that season pasture for a longer period of time and not switched at the beginning of the experiment.

Longer duration of the live trials of the anti methanogenic properties of the red seaweed are necessary to confirm that the effect does not decline during the supplementation with time. More research of the anti parasitic properties of the red seaweed both in vitro and in vivo is important in future.

Red seaweed might become a great tool for reducing climate footprint of the organic regenerative farms that already have been doing a lot for that purpose due to the successful carbon sequestration by the perennial pastures and other environmentally friendly practices.