Final report for FNE22-007

Project Information

This project evaluated whether pruning and nutrient amendments could restore productivity and soil health in an older, neglected chestnut orchard. We divided 56 trees into four 14-tree groups—pruned + fertilized, fertilized only, pruned only, and control—and applied pruning over three winters (2022–2024) with nutrient additions of ramial wood chips, minerals, and compost extract. Annual soil samples were analyzed for biological and mineral content, and nut yields were recorded for each group during the 2022–2024 harvests.

Soil tests throughout the project showed low total and active fungi and bacteria, a fungi-to-bacteria ratio favoring bacteria, and organic matter averaging about 4–5 percent, with little measurable change over time. Averaged across the three harvests and considering only trees that produced nuts, pruned + fertilized trees yielded 16.4 lb/tree, fertilized-only trees 13.2 lb/tree, pruned-only trees 15.8 lb/tree, and control trees 11.9 lb/tree. These results suggest a modest benefit from pruning, especially when combined with fertilization, though yearly variability and deer losses limit definitive conclusions. Heavy pruning delayed nut production for the two following seasons of the grant period and is expected to require several additional years for full recovery, while lighter pruning maintained or slightly improved yields.

Through 28 field days and workshops, including a 2025 hands-on compost-making event, we engaged about 50 farmers and land managers. Participants gained practical experience in pruning, harvest methods, and soil-health practices, and the findings are being shared through SilvoCulture’s ongoing regional outreach.

This SARE project will quantify changes in production and soil health as a function of pruning and nutritional inputs over three years. Based on the data, we will estimate the potential increase in income with continued treatment and compare with the expenses. This may provide some information on the viability of restoring mature chestnut trees through pruning and nutrition.

- To determine the effect on yield of pruning a neglected chestnut orchard

- To determine the effect of nutrient applications on soil health.

- To gather data on whether pruning and adding nutrition is cost effective for a neglected orchard

Tree crops like chestnuts take considerable investment of time and money to established before producing a yield that can generate income for the farmer. Chestnuts begin producing 7-8 years after planting seedlings and should begin to show profit around year 10. Neglected orchards of chestnuts and other tree crops exist in our region that have the potential to be profitable farming enterprises. Demonstrating that intensive pruning and nutrition increase yields to profitability, accompanied by outreach to orchard owners, will encourage orchard restoration.

Pruning removes dead and diseased wood, increases light and airflow and results in increased productivity. However, pruning large mature trees requires specialized equipment and skilled labor and is a costly endeavor. Farmers seek return on investment for such a large expense.

Good nutrition is also important for orchard trees, increasing their resistance to pests and disease and giving them additional energy for crop production. Ramial wood chips have been shown to increase yield and water retention when applied to agricultural soils. In addition, ramial wood chips feed the fungal components of soil which create symbiotic relationships with tree crops. Ramial wood chips are commonly available from arborists in most areas making them an accessible and affordable soil amendment. Enhancing mineral concentrations available to the trees will also increase their productivity and resistance to disease and pests. Finally, we include in this proposal the application of liquid nutrition such as compost tea but are waiting for preliminary test results before selecting what to apply.

We will estimate the expense and increased production on pruning mature chestnut trees and providing additional nutrition to shed some light on whether it is economically viable to restore a neglected orchardThese restored orchards can produce crops sooner and in larger quantities than newly planted orchards. They can be profitable businesses for farmers and employ workers in farm communities to prune trees and harvest crops. Demonstrating that unmaintained mature orchards can be profitably brought back into production may also protect mature orchards from being destroyed and save important varieties and genetics.

Jane's farming experience began in 2010 when she purchased a 5 acre farmette. She became involved in beekeeping and attended two beekeeping classes. She also raised chickens and experimented with gardening techniques. She planted 120 raspberry bushes and started a small apple tree orchard, and experimented with other fruit and nut trees, including hazelnuts, persimmons, and figs. In 2016, she moved to a 21-acre farm and has designed and planted 9 acres of chestnuts and 3 acres of pawpaws, hazelnuts, apples, and other nut trees. Preparation for planting included installation of swales and berms on contour to allow water harvesting. Companion plants such as comfrey, black currants, and false indigo were included in the design. She farms part-time and hires help to keep up with the farming activities. She is hopeful that the pawpaws will begin producing in 2022 and earn income. Chestnut plantings were begun in 2018 so will not be producing for another 5 years.

She recently purchased the 36 acre Morris Orchard property with which SilvoCulture had been working. This property includes a mixed tree crop orchard with 8 acres of hybrid chestnuts, 3 acres of black walnut, 2 acres of pecans and a few American persimmons, hazelnuts and shagbark hickories. Her work with SilvoCulture, Inc. has supported the notion that chestnut orchards can be profitable and she is interested in whether this applies to mature orchards.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

Research

Defining the test groups:

A section of the orchard's chestnut trees have been divided into four groups of 14 trees each (the whole orchard was not selected for this study due to the high costs of the arborist.) The groups were selected based on similar tree density and site conditions (see attached orchard schematic). Each group will be marked in the orchard using color coded flags. The groups will be assigned treatments: Group 1: pruning only, Group 2: nutrient application, Group 3: pruning and nutrient application, and Group 4: control, no treatment.

Treating test groups:

Trees in Group 1 and Group 3 will be pruned each winter for three winters. No more than 25% of the tree will be removed each year to ensure the health of the tree. The farmer will consult with the technical advisor and arborist as to the best approach to pruning the trees.

Trees in Group 2 and Group 3 will receive nutrient applications:

- Wood chips will be delivered by tree service companies and amassed on site. They will be kept in open piles not to exceed 20 yards each. Once 56 yards of wood chips are collected they will be spread through the orchard at a rate of 2 yards per tree in July 2022 and July 2023. Wood chips will be spread under the canopy of the tree but not on the orchard ground between trees. A tractor front loader sized to deliver the correct amount of wood chips for each tree will be used for spreading.

- Minerals: The local chapter of the Bionutrient Food Association is headed by Richard Jeffries who has advised us on mineral application. We will use rock dust from a local quarry but are not including this as a cost on this proposal since we will be getting a bulk supply for use on this orchard and elsewhere.

- Liquid compost soil drench: We are taking a preliminary soil sample in November 2021 for laboratory analysis and will consult with the laboratory and Dr. Elaine Ingham’s SoilFoodWeb School (https://www.soilfoodweb.com/) for the best product to apply. Our technical advisor, SilvoCulture, Inc., will pay for this preliminary expense. We will also refer to the Rodale Institute guide on compost teas (https://rodaleinstitute.org/blog/compost-tea-a-how-to-guide/)

Soil Health Analysis:

Based on recommendations from the Bionutrient Food Association, soil health will be measured using Earthfort Lab’s #2 package which tests for total/active bacteria, total/active fungi and protozoa, pH and #7 package which tests for pH, calcium (Ca), % humus, soluble salts, nitrates (NO3), ammonium (NH4), phosphate (HPO4), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), boron (B), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), sulfates (SO4), clorides (Cl). A composite sample will be taken from at least 8 locations within each test Group for a total of 4 samples per year to be sent for analysis

Background soil testing will occur in April of 2022 to establish existing soil health conditions of the site. Additional testing in April 2023 and April 2024 will be used to determine the effect of nutrient application on soil health.

Determining Chestnut Yields:

Each October during the grant period chestnuts will be gathered with the help of volunteers from all the tree groups for the duration of the harvest. Volunteers will be recruited through SilvoCulture’s email list. This has been successful for harvesting chestnuts from the orchard in 2020 and 2021.

Gatherers will be assigned rows to walk and methodically collect all fallen chestnuts from each tree in a group. Chestnuts will be collected into 5 gallon buckets marked with the color code for the tree group. Chestnuts will be kept separate per the test Group and sorted based on condition. Nuts will be sorted by the following criteria:

1) Marketable nuts as a raw product: must be free of disease and blemishes.

2) Seconds suitable for processing into value added chestnut products such as flour or beer but not suitable for direct sale: May have small blemishes both on shell of nut and interior but must otherwise be in good condition.

3) Nuts not suitable for direct sale or value added products: Are diseased or damaged to the point that they are unmarketable and not suited for creating value added products.

Nuts will be collected every other day to reduce loss from wildlife and weevils. All nuts will be given a hot bath at 120 degrees Fahrenheit for 20 mins to kill any weevil eggs present. This will be done using our SilvoCulture’s “Chestnut Dunker” which has been used successfully in 2020 and 2021 on chestnuts from the orchard. The dunker consists of a tank of water kept at a steady temperature of 120 degrees by a digital thermometer and propane heater.

The following data will be recorded:

-Yield of chestnuts from each tree group per season

-Cost of materials and labor for work done on each tree group

-Revenue of chestnuts based on price attained through local sales

We will analyze the data looking for statistical differences between nut yield/quality and soil health for the 4 test groups and the effects of yield on pruning and amending with wood chips a neglected chestnut orchard. Revenue from the chestnuts will be quantified through prices obtained from local sales and compared to the cost of work done on the orchard. Local sales will be made through SilvoCulture’s chestnut roast festival and our social network. Value added producers of bread and beer will be identified as buyers for quality chestnuts.

Activities Completed in 2022

Defining the test groups: Test groups were marked with different color marking flags to identify which trees belonged to which group. A change in treatment to groups was decided upon to allow for easier spreading of wood chips. Group 1 (Yellow) was pruned and fertilized, Group 2 (Green) was fertilized and not pruned, Group 3 (Blue) was not fertilized and not pruned and Group 4 (Red) was pruned and not fertilized.

First pruning of chestnut trees:

Trees in Test Groups 1 and 4 were pruned in March of 2022. Technical Advisor, Michael Judd met with an arborist on site and determined the best approach to pruning the trees over the three year grant period. The amount pruned from each tree varied depending on the amount of disease and dead wood in each tree. Photos for each of the trees in the grant were taken as a record of the pruning done to them. The second pruning of the trees will occur this February 2023 and will focus on shaping and training the new growth of the trees.

Soil Testing:

Background soil testing was taken for each of the test groups and submitted to EarthFort Lab for analysis. In addition to receiving soil tests results support staff met with EarthFort consultants for a review of the results.

Chestnut Harvest:

Chestnuts were harvested by support staff and volunteers and careful records were kept of yield and quality of chestnuts for each test group. 5 gallon color coded buckets were used to keep nuts from each test group separate.

Soil Amendments:

Throughout the 2022 summer, wood chips were collected on site from local arborists and kept in piles to begin composting. Soil amendments were applied in fall of 2022 after the chestnut harvest. Head of the local chapter of the Bionutrient Food Association- Richard Jeffries, advised Morris Orchard on how to apply compost extract and rock minerals to the test groups . Richard also provided the compost and rock minerals. Compost extract was applied using a backpack sprayer, rock minerals were broadcast by hand and wood chips were spread using a skid steer.

Support staff applied the following rates of amendments to each tree in each test group:

- 1 gallon of compost extract

- 1.5 yards of wood chips

- 1 quart rock minerals

Though an amount of 5 gallons of compost extract per tree was advised, support staff were only able to apply a gallon of compost extract in the allocated time. Morris Orchard is looking into a more efficient was of apply the extract for next season.

Only 1.5 yards of wood chips were applied instead of the planned 2 yards due to being unable to solicit the total amount needed from local arborists.

Activities Completed in 2023

Second pruning of chestnut trees:

The second pruning occurred in late winter of 2023. This pruning was lighter than the first and focused on selecting new suckers for continued growth and removing unwanted suckers to increase light and airflow. Some trees experienced wind damaged and lost limbs in 2022 and were pruned to reduce the damage to the tree.

Soil Testing:

The second set of soil tests was taken in the spring of 2023 and sent to EarthFort for soil biology tests. EarthFort discontinued their mineral soil reports 2023 so additional samples were sent to the University of Delaware for mineral analysis.

Chestnut Harvest:

Chestnuts were harvested by support staff and volunteers and careful records were kept of yield of chestnuts for each test group. 5 gallon color coded buckets were used to keep nuts from each test group separate. The task of picking up all nuts regardless of quality, and sorting them by hand to determine percentage of marketable versus unmarketable nuts was found to be too time consuming in 2022. In 2023 we focused on only picking up all the good nuts in the orchard to get accurate data of marketable yields and in order to have enough time to collect all the good nuts in the test plots.

Soil Amendments:

Throughout the 2023 summer, wood chips were collected on site from local arborists and kept in piles to begin composting. Wood chips were spread in the fall of 2023 at a rate of 2 yards per tree.

SilvoCulture consulted with Leslie Lewis of Living Systems Soil regarding the application of compost extract in the orchard test groups. Under Leslie’s guidance, SilvoCulture decided not to use the same compost from 2022 for the orchard. Instead, SilvoCulture staff constructed a biologically active compost following Leslie’s direction. This compost is still in the composting process and will be used in the spring to create an extract for the test groups. The compost extract will be applied by drilling ½” holes, 4” deep into the soil around the tree roots and pouring the extract into the holes.

Activities Completed in 2024

Third Pruning of Chestnut Trees:

The third and final pruning of the project took place in late winter 2024, focusing on selecting and thinning new suckers to support the continued development of scaffolding branches.

Soil Testing:

The third round of soil tests was conducted in spring 2024 and sent to EarthFort for soil biology analysis and the University of Delaware for mineral composition testing.

Chestnut Harvest:

Support staff and volunteers harvested chestnuts while maintaining detailed yield records for each test group. Five-gallon color-coded buckets were used to keep nuts from each group separate.

Activities Completed in 2025

Soil Testing:

The final set of soil tests was taken in the spring of 2025 and sent to EarthFort for soil biology tests and to the University of Delaware for mineral analysis.

Hot compost making workshop spring 2025:

A hands on workshop was held in which participants made a microbially rich compost and learn about the potential of such composts to increase plant and soil health

Methods as Proposed

Soil and Yield Results Summary

Initial Soil Tests (Spring 2022)

Baseline soil tests revealed that the chestnut orchard soils were in poor biological condition for supporting tree health and nut production. Across all treatment groups, the following conditions were observed:

-

Total and active fungi were very low.

-

Total and active bacteria were low.

-

The fungi-to-bacteria ratio was too low in fungi for optimal tree health.

-

Organic matter was low (~4.5%).

-

Most bioavailable nutrients were below optimal ranges.

2022 Yield Data

The first harvest showed clear differences among treatments, with fertilization supporting higher yields but pruning reducing production where applied heavily.

| Group | Treatment | Total Yield (lbs) | % Marketable | % Seconds | % Unmarketable | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Yellow | Pruned + Fertilized | 44.1 | 55% | 14% | 31% | mix med/large, some trees heavily pruned and not bearing |

| 2 Green | Fertilized only | 172.9 | 40% | 34% | 27% | mostly small nuts |

| 3 Blue | Control | 127.0 | 43% | 20% | 37% | small/medium |

| 4 Red | Pruned only | 136.4 | 40% | 29% | 31% | medium |

Fertilized-only plots (Green) had the highest yield, while pruned+fertilized plots (Yellow) were lowest due to severe pruning that set back nut production in some trees.

Spring 2023 Soil Results

Soil analyses showed little improvement across treatments:

-

Total and active fungi remained very low.

-

Total and active bacteria were low.

-

Fungi-to-bacteria ratios continued to favor bacteria.

-

Organic matter ranged 3.1–6.4%.

2023 Yield Data

| Group | Treatment | Total Yield (lbs) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Yellow | Pruned + Fertilized | 145.5 |

| 2 Green | Fertilized only | 183.5 |

| 3 Blue | Control | 224.0 |

| 4 Red | Pruned only | 192.5 |

In 2023, control plots (Blue) produced the highest yields, while fertilized plots were moderate. Trees that had been heavily pruned in 2022 (especially Yellow plots) remained slow to recover, but lightly pruned trees performed well and in some cases out-yielded unpruned controls.

Spring 2024 Soil Results

Soil conditions remained poor overall, with incremental shifts but no dramatic improvements:

-

Fungal biomass and activity were still very low.

-

Bacterial levels were low but relatively more stable.

-

Fungi-to-bacteria ratios were consistently below optimal levels.

-

Organic matter ranged 4–5.7% (similar to past years).

2024 Yield Data

| Group | Treatment | Total Yield (lbs) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Yellow | Pruned + Fertilized | 154.75 |

| 2 Green | Fertilized only | 199.0 |

| 3 Blue | Control | 146.5 |

| 4 Red | Pruned only | 144.0 |

By 2024, fertilized-only plots (Green) again outperformed all other groups, while pruned-only plots (Red) lagged. Heavily pruned trees from 2022 still did not return to full production.

Spring 2025 Soil Results

Most recent tests (2025) confirmed the longer-term soil biology patterns:

-

Fertilization (Green) consistently supported higher fungal biomass, better fungi-to-bacteria ratios, and greater microbial carbon and nitrogen.

-

Pruning without fertilization (Red) corresponded with the weakest soil biological health.

-

Control plots (Blue) maintained adequate bacterial levels and competitive yields in some years, but soil health did not improve.

-

Pruned + fertilized plots (Yellow) recovered yields gradually, but heavy pruning in 2022 created a lag that fertility alone did not overcome.

The goal of this project was to evaluate the economic viability of pruning versus fertilization of an old chestnut orchard. We applied four treatments: pruned + fertilized (Yellow), fertilized only (Green), control (Blue), and pruned only (Red). Soil health was measured through biological and nutrient analyses, while nut harvests were weighed and categorized by market class.

The results showed patterns, but not as strong or conclusive as expected. Several factors complicated interpretation:

Heavily vs. lightly pruned trees. Roughly half of the pruned trees were cut back severely to remove diseased wood. These trees largely did not produce nuts during the grant period, depressing yields in the pruned groups. In contrast, lightly pruned trees showed competitive or even higher yields per tree than unpruned trees. For example, in 2023, lightly pruned and fertilized trees averaged 20.8 lbs per tree, compared to 13.1 lbs in fertilized-only trees. This indicates that pruning, when done moderately, can increase production, but heavy pruning requires a multi-year recovery period.

Soil results. Soil tests did not show the improvements anticipated. Fungal biomass, fungi-to-bacteria ratios, and microbial carbon and nitrogen remained below optimal across treatments. We believe this is because the compost used was not biologically active enough, and because woodchip mulch decomposes slowly. Over a longer timeframe, and with biologically active compost, greater improvements would likely be seen.

Yield results. Fertilization (Green) provided the most reliable yield increases, leading in 2022 and 2024. However, when heavily pruned non-producing trees are excluded, pruned groups outproduced unpruned groups on a per-tree basis, regardless of fertilization. This suggests pruning has economic value if assessed over a longer horizon than the grant allowed.

Pest pressure. Heavy deer and rodent feeding reduced yields substantially, with staff estimating that up to half of the nuts were lost in some years. Allowing hunting in 2023 and 2024 helped reduce this pressure but it remains a limiting factor.

Conclusions. Fertilization emerged as the most consistently viable short-term strategy, supporting higher yields and modest soil improvements. Pruning remains important for long-term orchard restoration, but its economic benefit depends heavily on pruning intensity. Light pruning can boost production, while heavy pruning delays it for years but may be necessary to restore declining trees. Soil health improvements require higher-quality biological inputs and more time to manifest.

As a result of this project, SilvoCulture and Morris Orchard have adopted lighter pruning practices, introduced hunting for deer control, and are sourcing more biologically active composts for soil treatments. These changes are expected to improve both economic returns and soil health over time, strengthening the long-term viability of chestnut production.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Completed 2022

Fall Harvest 2022 (Workshop/ Field Days):

SilvoCulture staff reached out via Facebook and through our distribution list of 964 people to publicize the harvest event: we received 68 emails from people interested in volunteering, of which 20 showed up. The harvest was held from 9/20 to 10/12/22. Each of the four research quadrants were given a color and buckets marked with that color were used for the harvest and records were kept of the yields. Volunteers also helped with post-harvest activities including dunking the nuts in the hot water heater and sorting the nuts to remove bad ones. The volunteers consisted of people from diverse backgrounds interested in chestnuts for a variety of reasons. Of these, the most common were farmers interested in chestnuts as an agricultural crop and European and Asian immigrants with a fondness of chestnuts from childhood.

Workshop field days: 10

Farmers participating: 8

Completed 2023

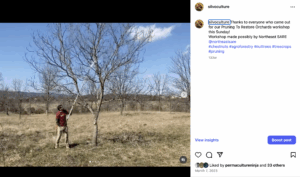

Workshop: Pruning to Restore Orchards

The workshop Pruning to Restore Orchards was held on Sunday March 5th from 1-3pm.

Taylor Logsdon, SilvoCulture’s operations director, gave an introduction to SilvoCulture and the work and research being done through the NorthEast SARE grant. Mathew Jacobsen, a local arborist who has been pruning the orchard, gave a demonstration on pruning and walked through his decision making process for the attendees.Michael Judd, SilvoCulture’s technical director, spoke on the purpose and effect of pruning trees as well as speaking more broadly on chestnuts and tree crops for the mid-Atlantic. Twenty (20) people attended the workshop. Of the attendees, the majority were farmers interested in agroforestry or home gardeners with an interest in tree crops. This included farmers from the BIPOC community. Attendees learned about the principles of tree pruning, the effect of pruning and chestnuts as an agricultural crop.

Workshop: Soil Health 101

On Oct 7th, 2023 SilvoCulture hosted Leslie Lewis of Living Systems Soil at SilvoCulture’s headquarters in Myersville, Maryland for the workshop Soil Health 101. This workshop gave an introduction to the soil food web and principles for creating and maintaining healthy soils. Participants learned about the soil food web, soil biology for home gardens and soil biology for tree crops. SilvoCulture staff gave an introduction to the SARE grant project at the beginning of the workshop. Twelve (12) people attended the workshop. The participants were a mix of farmers and home gardeners including BIPOC farmers.

Fall Harvest 2023 (Workshop/ Field Days)

SilvoCulture staff used Facebook and our email list to publicize the 2023 harvest and received 40 new emails from people interested in volunteering. 31 people came out and assisted with the chestnut harvest. The harvest was held from 9/22 to 10/16. The same harvest protocol was used as in 2022 except that only good nuts were collected.

Workshop field days: 11

Farmers participating: 31

Introduction to SARE Grant Social Media Video

A first draft of the project video was completed in 2023. The footage documents key activities — pruning, soil testing, and harvest — while providing an overview of the grant’s objectives. Although the draft video did not fully meet expectations for immediate release, the material is valuable. SilvoCulture is retaining this footage to be edited and incorporated into future outreach, where it will support promotion of agroforestry practices and chestnut production. See video under "Information Products."

Fall Harvest 2024 (Workshop & Field Days)

SilvoCulture promoted the 2024 harvest through Facebook and email outreach, generating 40 new email contacts from interested volunteers. Eleven volunteers participated in the harvest, which ran from September 17 to September 30.

- Workshop field days held: 6

- Farmers participating: 11

Completed 2025

Biological Compost Making Workshop:

Leslie Lewis of Living Systems Soil LLC, lead a hands on workshop and discussion on creating biologically rich compost as a soil inoculant. Attendees participated in building the compost pile and learned about proper technique, materials, ratios and care to produce biologically rich compost. There were 10 attendees.

Workshop field days: 1

Explanation of Activities Not Completed as Originally Planned

-

Final Outreach Workshop

-

The proposal included a capstone “Presentation of Project Results” workshop. Instead of holding a stand-alone results presentation, we delivered a hands-on biological compost workshop in spring 2025. This event combined discussion with a practical demonstration of creating microbially rich hot compost, and gave participants tools directly applicable to soil health improvement in tree crop systems.

-

-

Conference Presentations

-

We intended to present project results at the Northern Nut Growers Association, Chestnut Growers Association, and Future Harvest conferences.

-

Barriers:

-

NNGA and Chestnut Growers Association meetings were prohibitively far to attend within the project budget.

-

Our application to present at Future Harvest was submitted but not accepted.

-

-

While these presentations did not occur during the grant term, we continue to seek opportunities to share findings through other regional channels and online platforms.

Despite these adjustments, the project successfully engaged over 50 farmers through workshops, field days, and volunteer harvest events. Participants gained hands-on experience with orchard restoration practices and soil health principles. While some outreach shifted in format, the overall goals of farmer education and knowledge transfer were met, and findings will continue to be shared through future presentations, publications, and online media.

-

Learning Outcomes

In order to collect information regarding learning outcomes, SilvoCulture staff sent a survey email after the Pruning to Restore Orchards workshop. The survey received only two responses. Because of the low response, SilvoCulture staff relied on in-person conversations at the workshops to collect information on learning outcomes. The farmers that attended our workshops and volunteer chestnut harvest days reported a better understanding of the chestnut harvesting process, including:

- the need to harvest frequently and continuously throughout the harvest period

- the weevil life cycle and effect on nuts

- the competition from deer and rodents

- how to identify a good nut from a bad nut

- labor and time required to harvest nuts

- principles of tree pruning

- principles of soil health

- chestnuts as an agricultural crop

- tree crops in the mid-Atlantic

Project Outcomes

Through this project, we gained practical insights into how pruning and fertilization affect both the productivity and the long-term management of older chestnut orchards. While the data collected were not always clear-cut — especially where heavy pruning delayed nut production — the process has shaped our approach and led to meaningful changes in practice.

On our farm:

-

We now approach pruning with greater care, prioritizing lighter cuts that maintain production while still improving tree structure. This change has already reduced stress on trees and lowered the risk of lost yields in the short term.

-

We are sourcing biologically active composts and applying them in ways recommended by soil health professionals. This adjustment has reduced wasted inputs and increased our confidence that fertility practices will have measurable biological benefits over time.

-

Pest pressure was a major challenge, and we began allowing controlled hunting on the property. This has improved nut survival and reduced frustration for staff and volunteers.

For SilvoCulture and other growers:

-

The project highlighted the economic viability of fertilization as a stand-alone practice, providing growers with confidence that this investment can yield short-term returns.

-

Our experience also underscores the importance of patience with orchard restoration: heavy pruning may be necessary for tree health, but its benefits are realized only over multiple years. Sharing this lesson helps other farmers set realistic expectations when rejuvenating older orchards.

-

The soil testing and yield tracking process, while labor-intensive, deepened our understanding of orchard systems and created resources we will continue to share with the regional nut-growing community.

Takeaway:

One clear takeaway was the performance of the lightly pruned trees. When considered separately from heavily pruned trees, these trees not only maintained production but in some cases outproduced unpruned controls. This demonstrated to us and our technical advisor that careful, moderate pruning can both improve orchard structure and increase nut yields — a practice we will continue to refine and promote.

Overall, the project has increased our confidence in chestnut orchard management, reduced uncertainty about how to prioritize labor and inputs, and positioned us to share practical, experience-based recommendations with other farmers working to restore and manage older orchards.

Our original goal was to assess the economic viability of pruning versus fertilization of an older chestnut orchard. In practice, the project revealed both methodological strengths and challenges that shaped the results.

Pruning intensity (heavily vs. lightly pruned trees).

Upon inspection, our technical advisor and arborist determined that some trees required very heavy pruning to remove diseased or decayed wood. In Group 1 (Yellow), 7 of 14 trees had major limbs removed, and in Group 4 (Red), 4 of 14 trees were similarly cut back. These trees produced little or no nuts during the grant period, depressing overall yields for those groups. By contrast, lightly pruned trees performed well. When non-producing heavily pruned trees were removed from the dataset, lightly pruned trees outproduced unpruned trees on a per-tree basis, regardless of fertilization. For example, in 2023 lightly pruned and fertilized trees averaged 20.8 lbs per tree compared to 13.1 lbs in fertilized-only trees. This distinction shows that pruning can improve nut production if applied moderately, while heavy pruning requires a multi-year recovery period. Going forward, pruning methodology should be refined by balancing tree health needs with production goals.

Labor in yield data collection.

We chose to record marketable, seconds, and unmarketable nuts separately. While this information is valuable, the process proved very labor intensive. Volunteers harvested all nuts from the orchard floor, and support staff later sorted and weighed the categories. This significantly increased labor hours and slowed data processing. In future studies, a simplified approach (e.g., recording only marketable vs. total yield) may strike a better balance between useful data and efficient collection.

Pest pressure.

Deer and rodent predation had a major impact, with estimates that up to half of fallen nuts were lost in 2022. Beginning in 2023, Morris Orchard permitted hunting, which reduced pressure somewhat, but deer and rodents remain a persistent challenge. Pest management must be integrated into chestnut orchard trials, as losses can overwhelm treatment effects.

Soil results.

Soil health tests did not show the improvements we had hoped for across the grant period. Fungal biomass, fungi-to-bacteria ratios, and microbial carbon remained low. We believe this is due to two factors: (1) woodchip mulch requires more time to decompose before supporting fungal activity, and (2) the compost we initially used for extracts was not biologically active enough. In 2023, with guidance from Living Systems Soil LLC, SilvoCulture began producing biologically active compost extracts in-house and applying them in targeted ways. We expect longer-term monitoring will be required to see measurable improvements.

Revisions in methodology and areas for further study.

This project suggests that future research should:

-

Separate heavily pruned and lightly pruned trees at the outset of the study, rather than combining them into one treatment group.

-

Simplify nut quality data collection to reduce labor demands.

-

Extend monitoring periods for soil health, particularly where woodchips are used to build fungal biomass.

-

Pair orchard restoration research with stronger pest control measures to reduce losses.

Who benefits from this knowledge.

Chestnut growers across the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions, particularly those managing older or decayed orchards, stand to benefit most. These results highlight that fertilization can deliver short-term yield gains, while pruning requires a nuanced, multi-year approach. Even though soil health results were limited, the lessons learned will help growers avoid pitfalls, refine methods, and set realistic expectations when restoring old orchards.