Final report for FNE22-010

Project Information

This project tested how to cost-effectively establish willow and poplar tree fodder blocks in a riparian silvopasture buffer by comparing on-farm vs. purchased plant material and evaluating how much site preparation and protection is needed for trees to survive and thrive. We propagated willow (and initially poplar) from on-farm and local sources in nursery beds (including “air-prune” beds) and attempted to root purchased material for comparison. We established three fodder block plots with contrasting site-prep strategies—Site A tarped (Apr–Aug 2023), Site B excavated/bermed/mounded (Nov 2023), and Site C forest-mulched/topsoil spread (Spring 2024)—and protected all sites with a perimeter 3D deer fence plus short tree tubes and fiberglass stakes. We monitored survival and measured growth over three seasons, shifting from monthly measurements to annual height measurements, and analyzed “thrivability” using browse-relevant thresholds of 48" and 72".\

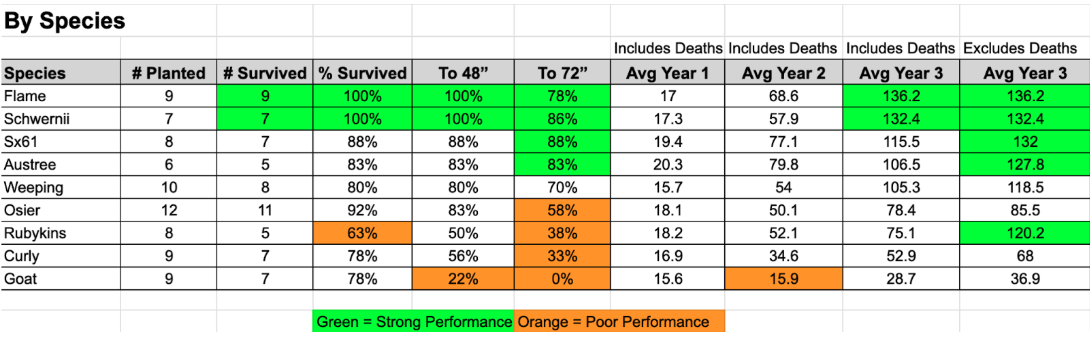

Despite early delays and setbacks, the project ultimately established all three sites successfully and produced clear performance differences by site prep and variety. In total, 79 trees were planted and 67 were alive by year 3 (85% survival); however, “thrivability” varied strongly by plot. Plot B (excavated and mounded) was the clear top performer with an average height of 114.8" and 77.78% of trees reaching >72" by year 3, suggesting faster escape from browse pressure and the potential to reduce fencing sooner. Plot C averaged 83.7" with 78% survival and 51.85% reaching >72", while Plot A was lowest at 65.1" and 47.62% reaching >72", indicating that tarping did not provide enough establishment advantage under these conditions.

Variety results also separated into tiers: Flame (9 planted) had 0 deaths and the highest year-3 average height at 136.2"; Schwerinii (7 planted) had 0 deaths and averaged 132.4"; Sx61 (8 planted) averaged 115.5" (or 132" excluding 1 death); and Austree (6 planted) averaged 106.5" (or 127.8" excluding 1 death). Using browse thresholds, Flame/Schwerinii/Sx61/Austree collectively had 83% of trees reach >72" by year 3, while slow growers like Goat averaged 28.7" and had 0 trees reach >72".

We shared results through 4 consultations, 3 tours, 1 presentation, and 5 workshop/field days. We are publishing a series of articles in early 2026 (including the approved 3D fence and Wondrous Willow pieces) to distribute the findings in more digestible segments via our Substack at https://wellspringforestfarm.substack.com

This project seeks to answer two questions:

1.What is the cost and benefit of producing tree plant material on the farm vs purchasing it in?

2.What intensity of site preparation and tree protection is necessary for trees to thrive in a fodder block?

Objectives:

1) Harvest local sources of willow and poplar varieties to propagate in an on-farm nursery. Compare costs and growth rates with cultivars available from commercial nurseries.

2) Prepare three planting blocks with varied intensities of site prep before planting. Install fencing and mulch strategies for each intensity.

3) Monitor and measure percent survival, growth rates, herbivory damage, and presence of disease for each tree monthly for two growing seasons

4) Compile data and report on costs in time and materials for establishing each combination of acquiring plants and site prep intensity

5) Develop a guidebook summarizing the findings and recommendations for farmers who are installing tree fodder blocks. Share publicly via online webinar and field days in 2023 and 2024.

The findings from this effort will provide other farmers with a better understanding of how different potential outcomes from these strategies contribute to success of plantings and keep costs down, thereby, reducing their risk and making decisions easier.

The concept of tree fodder is an intriguing and exciting aspect of a holistic grazing system that can both benefit livestock grazing systems as well as meet environmental goals for small farms in the Northeast. Tree fodder blocks are dense plantings of trees that provide a strategic reserve of fodder for excessively dry, drought, or even overly wet conditions. Many species can be utilized, but Willow (Salix spp.) and Poplar (Populus spp.) are common staples.

With environmental changes emerging as a central challenge to maintaining good grazing forages for livestock, trees offer a critical solution to a future climate that is more and more unpredictable. One season may be excessively dry, and the next excessively wet. This leads to a lack of quality forage from traditional grass/legume/forb stocks, and unmanaged waterways (riparian zones) can flood and initiate pastures with excess water, sediments, and lead to erosion of these valuable pasturelands. The addition of trees to grazing systems (silvopasture) can provide shade, shelter, an alternative food source, and buffer many of the water issues present in farms throughout the Northeast.

Tree fodders are already established strategies in varying climates around the world (such as New Zealand and parts of Asia and Africa) that experience more challenging (excessively wet and dry) environments when compared to the historic trends in the Northeast. They are a clear strategy for increasing the stock of reliable food sources for animals in both wet and dry seasons, as woody plants and trees tend to be better adapted to these variable conditions.

While the nutritional and medicinal value of willow and poplar as tree fodder is well established in research, the process to effectively establish meaningful plantings on Northeast farms is relatively unknown. Questions remain about cultivar selection, seedling development, layout design, soil prep, planting, and protection of young seedlings with the specific purpose of providing reliable tree fodder for the farm.

Utilizing willow and poplar in a riparian tree fodder block establishment has the potential for a win-win scenario that benefits not only the livestock but also the larger farm ecosystem. More specifically, many farms in the region have neglected and/or ignored riparian (water) pathways that would benefit from buffer plantings. Rather than grazing livestock right up to the edge of (and often within) a waterway, tree fodder blocks can offer an excellent solution to provide productive vegetation for livestock whilst also protecting the water way. The contribution of tree fodder to the livestock enterprise incentives the farmer to manage a riparian buffer. These areas often border pasture and if strategically developed, can provide an easily accessible source of fodder just outside the fenceline.

Even while the agroforestry practice of silvopasture is well documented as providing benefits to farm ecosystems and the productivity of livestock, adoption remains low. This is in part due to farmer unfamiliarity with tree planting and establishment, and in part because there is too much risk in experimenting with strategies to ensure an investment in trees pays off. Moreover, while techniques are well established for individual tree planting, there is not a well articulated process for specifically installing tree fodder blocks effectively and with efficient use of labor and materials. The Northeast needs “turn key” solutions for tree establishment that can work in many farm contexts. This project aims to test several pathways to success and report back on the best practices for establishing tree fodder blocks.

Our project builds off of previous research on our farm to document the nutritional value of tree fodders by testing several tree establishment processes to determine their costs and effectiveness on tree survival and growth. Successfully established fodder blocks will provide the farm with a sustainable source of nutritious and medicinal forage, especially for resilience during periods of drought. While growing, the trees will support water quality and mitigate negative effects from flooding. Results from the project will be applicable in many northeast farms, and can offer a template for success in other locations.

Wellspring Forest Farm has been in operation by Steve and Liza Gabriel since 2011 in New York, producing a wide variety of products on 20 acres of pasture and woodlands, including pastured poultry and sheep, mushrooms, maple syrup, elderberry, nursery trees. Gross receipts from product sales have been at least $10,000 from the beginning, with around $50k in sales in 2024. We sell at the Ithaca Farmers Market, wholesale to restaurants, and offer a mushroom CSA direct to consumers. The farm has also successfully managed multiple grant and NRCS cost share projects over its tenure. With education being a primary driver, we engage routinely in farm tours, workshops, speaking engagements at conferences, etc and believe deeply in the importance of sharing what we've learned and benefitting from the insights and experiences of other farmers in our community.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

- (Researcher)

Research

Objective #1:

On farm and local sources of 3 willow and 3 poplar varieties will be identified in March 2023 and 40 cuttings taken from each of the 6 varieties (300 total). Cuttings will be between ½” and ¾” thickness and cut to 12” long. Cuttings will be stuck directly into irrigated nursery beds at a 4”- 6” spacing and mulched with sawdust. Labor hours and material costs for this will be recorded while the cuttings are monitored during the 2022 growing season. 18 of the best performing cuttings of each variety will be lifted in April 2024 and planted into each of the three fodder research plots so there are 6 replicates for each plot (54 trees total).

Commercial sources of 3 named willow and 3 named poplar varieties will be ordered (30 of each or 180 total) to plant alongside harvested farm stock in Fall 2023 or Spring 2024, as conditions allow. Costs of these trees will be recorded. Each tree will be given a unique identifier and tagged with a metal horticultural tag for data recording purposes. There will be 6 replicates of 6 varieties (3 on site and 3 purchased) for two species, willow and poplar, in 3 test plots (low / medium / high intensity) for a total of 216 trees planted into research plots, with 72 trees per plot.

Trees will be planted on a 3’ x 3’ spacing and randomized in their arrangement within the plot. All trees will be dipped in a beneficial mycorrhizal root dip and planted with a tree spade to a depth appropriate to their root growth.

Each plot will encompass a space that is 40 feet by 50 feet or 2,000 square feet of planting space, which allows for 12 rows of 6 trees at the above spacing. Given the variability of the riparian areas the plots may not be perfect rectangles but will contain the above parameters within +/- 100 sq feet. See the attached map for proposed test sites. Plots will be prepared in 2022 prior to planting, using machinery to address water erosion issues if present.

Once both sets of trees are planted, growth rates will be measured for each tree once per month from May 1 through October 1 for 2023 and 2024, along with recording survival and any observations on pest or disease issues. Growth will be measured in cm and recorded.

Objective #2:

Each test plot will have a soil test conducted annually in the Spring of 2023, 2024, and 2025. Beginning In April of 2023, two of the three plots will be prepared for planting in 2023. Some previous erosion and disturbance in the treatment areas will be addressed with an excavator before plot prep.

The low intensity plot will be prepared just before planting in April 2024, where the site will just be mowed/week whacked prior to planting. The medium plot will be mowed/weed whacked and then covered with high density tarps for one year. The high intensity plot will be mowed/weed whacked and then tilled with BSC with an amendment of on-farm compost added and then mulched to a 3” depth with hardwood wood chips. (See table 1)

Fencing to prevent deer damage for each plot will be installed directly after planting in Spring 2024. For the low intensity plot, 8 foot T posts will be installed every 10 feet and three strands of non-electrified strand will be stung with flagging draped every three feet as a deterrent. The medium intensity treatment will include the installation of a “3D” fence system that includes one fence set at 6 feet tall with two strands (top and bottom) and a second run of fence set 3 feet outside the perimeter of the first fence at 4 feet with a single strand that runs 2 feet off the ground. All strands on the 3D fence will be electrified using energizers and baited for 2 months after installation. The high intensity plot fencing will consist of Premier One’s 19/68/2 Anti-Deer netting (two rolls) installed and electrified.

Mulching for each plot will follow planting as prescribed. For the low intensity plot, no mulch will be added and competing vegetation will be weed whacked 1 - 2x per season if and when vegetation gets at least 10 - 12” tall. For the medium intensity site, sawdust will be applied as mulch at a depth of 4 - 6”. For the high intensity site, 2 - 3” of fresh wood chips will be added at the time of planting.

|

LOW |

MEDIUM |

HIGH |

|

|

Site prep / planting |

Mow or weed whack before planting |

Tarping for 1 year before planting |

Till / compost / mulch |

|

Browse Protection |

Single strand fence |

3D fence |

Premier Deer fence |

|

Mulch |

None, weed whack 1 - 2x per season |

Sawdust |

Woodchips |

Table 1: Summary of plot treatments

Objective #3:

Once the three plots are established, the bulk of the remaining work will be to monitor and observe the survival, growth rate, and any pest or disease issues that arise in the plots. Each plot will be visited weekly for observations, which will be recorded as qualitative findings along with any documented evidence of animal presence on the trail cams. Once per month each tree will be measured for growth rates and recorded as quantitative findings. Each plot will be equipped with two trail cams to capture any activity from deer. Observations and data collection will occur from May 1 - October 1 in 2024 and again in 2025 during the same timeframe.

Objective #4

As data collection is completed for each phase, we can complete analysis. Our assumption is that any benefits for site prep and mulching will be reflected in tree survival and growth, while the browse protection in our assessment of damage to the plants. While we recognize we are compounding variables in this approach, we are not seeking to isolate any one aspect of tree establishment but rather explore the relationship of investing time versus money into a particular approach intensity. Some combination of these efforts may prove reasonable, for instance if deer browse is low in all plots but growth rates correlate to soil prep, a less intense method of fencing could be recommended as a conclusion along with a more intensive approach to soil prep. We will be able to break out labor and material costs for the different aspects of the treatments also, so we can utilize a wide variety of combinations in our reporting.

Objective 5:

Following analysis our project team will draft and develop a research guidebook of 5 - 10 pages that summarizes the efforts with pictures and graphics and breaks down our learning both in the quantitative data and qualitative observations of the project as experienced by the participants. This brief will be published to our websites (farm website and SilvopastureBook.com) and shared during outreach activities, described below.

The start of this project was delayed this year (2022) for two main reasons; 1) we encountered issues with our plans to restore the creek bed before planting fodder blocks because of slowdowns working with local NRCS / Soil and Water agencies, and 2) the outbreak of the Spongy Moth (Lymantria dispar) caterpillar led to almost 100% mortality of our willow cuttings. We'd never experienced such a devastating loss, as usually cuttings are quite easy to produce in previous years.

As a result, we asked SARE to delay our end date and allow us to just push all research and activities back one year. We have changed the date in the above description to new targets.

We did successfully collect cuttings and develop a procedure for starting them in "air prune" beds, which were also constructed and tested. This nursery elements proved to be a marked improvement over previous methods of propagation of cuttings (in ground beds)-- while almost all of the willow and poplar suffered at the hands of the spongy moth, we had elderberry cuttings in the beds that thrived and produced impressive root systems. We do think this will allow for a good strategy to propagate willow/poplar for next year and allow for healthy root growth.

According to pest experts, the spongy month epidemic in our area should subside next year, as the cycle of intense impact of the population explosion tends to two years, and 2022 was the second season. Even still, we will plan on extra monitoring and treatment if necessary of the beds (using Bacillus thuringiensis kurtaki (Btk) approved in Organic production)

2023 Update

For this season, we took cuttings of willow and poplar from the farm landscape and also local known cultivars of willow and unknown varieties of poplar. We planned to match this effort with the cost of purchasing cuttings, which we did from Vermont Willow Nursery (average cost of $2.90 per cutting) and hybridpoplars.com (average cost .56 per bud cutting).

Unfortunately, the ordered stock did very poorly in our rooting beds both in the field and woods, with near complete mortality, while the cuttings we took did quite well. Some combination of management from the suppliers (cuttings are often stored in a cooler or freezer for a long time?) and our management (we didn’t get everything out into the beds as quick as we’d have liked) probably led to this high mortality. The Poplar trees were received in early March but sat in our cooler (packed in wet peat) until the end of the month. The Willow was ordered in March but didn’t arrive until late April, so may have experienced more stress in storage at the source farm.

Thus, as the season progressed and we could see the purchased stock wasn’t going to thrive, we had to pivot our plan to plant a mix of poplar and willow to just willow, but we expanded from the original 6 varieties (3 willow / 3 poplar) to include 9 varieties of willow we had also growing in the nursery, for other uses on the farm. We are working now with these varieties in our fodder plots. We don’t see this change as problematic since we are working to discover viable establishment strategies of fodder blocks and learning from the process along the way.

|

Common Name |

Latin Name |

Source |

|

Purple Osier |

Salix purpurea (Streamco) |

Wellspring Forest Farm |

|

Flame |

Salix 'Flame' (Wild hybrid) |

Wellspring Forest Farm |

|

Austree |

Salix matsudana X Salix alba |

Wellspring Forest Farm |

|

Weeping |

Salix babylonica |

Wellspring Forest Farm |

|

SX-61 |

Salix sachalinensis |

Food Forest Farm |

|

Goat |

Salix caprea |

Food Forest Farm |

|

Rubykins |

Salix koriyanagi |

Food Forest Farm |

|

Curly |

Salix matsudana |

Wellspring Forest Farm |

|

Schwerinii |

Salix schwerinii |

Food Forest Farm |

Local cuttings were taken in the last two weeks of March, and stuck immediately into beds. We prepped in our field near the greenhouse, as well as in our air prune beds in the “woodland nursery.” We did this to provide a buffer of options in case something went wrong. We were thinking more in anticipation of possible drought, which might stress the field cuttings, but in fact the major event was a very warm April that led to a lot of quick leaf out of the cuttings, followed by a very devastating hard frost on May 17, where it was recorded to drop to 23F at our greenhouse weather station. The combination of rapid leaf out from the oddly warm spring and this event dealt a devastating blow to the cuttings in the field planting, yet the cuttings in the forest nursery were less harmed and recovered almost 100% across the planting.

This spring, we also did site analysis and prep, sampling the three planting sites on 4/5/2023 and receiving results from the DairyOne lab for each site. All three sites have low Phosphorus (common on NY pasture lands) and high levels of K, Ca, and Mg. The pH for all sites was around 6.2 - 6.4 so suitable for willow, the most notable outlier was that each site had relatively high organic matter with site A at 8.2%, site B at 11.3%, and site C at 9.2%.

Site prep included excavator work in April, to address water flow issues in the B to C area and mowing site A. Some adjustments to the original plan to differentiate site treatments was necessary due to some unexpected characteristics the sites presented. We were able to tarp Site A on August 7, which was sufficient after 3 months to remove and plant. We decided against tillage in any of the sites because the wetness of the soil didn’t allow for a BCS to work effectively. And instead of three distinct fencing systems, we decided to focus on a perimeter 3D fence that encapsulated the three sites, since we were also installing a 3D fence on the other end of the farm as part of another agroforestry tree project.

|

Site A |

Site B |

Site C |

|

|

Site Prep |

Tarping |

Excavate and Berm |

“None” (topsoil spread) |

|

Fence |

3D perimeter |

3D perimeter |

3D perimeter |

|

Mulch |

Woodchips |

Sawdust |

None/Weedwhack |

A major factor in decision making this season was the substantial and persistent rain we experienced after a six week dry period in April and May. The cuttings looked well developed in Fall and so we prepared to plant out the sites. We were able to plant out Site A on November 10, but Sites B and C were heavily disturbed due to a new water line that was being installed. While we hoped the soil would dry out enough to plant, ultimately we decided it was best to wait to plant out the remaining sites in Spring 2024 and cover the remaining cuttings in the nursery with a deep bed of wood chips to protect from freezing temperatures. The 3D fence was fully completed and working with 8 - 10k volts by December 5, after much troubleshooting!

Outputs

In addition to the field work described above, we are working on some materials that will be part of the final share out of the project.

Initial database/literature review of Willow; we are working with Jeff Piestrak of FLX Agroforestry Solutions to review existing research and develop profiles of willow as a fodder species and and specific information on the cultivars we’ve settled on using

3D Fence Article: We have a draft of an article describing our process of planning and installing a 3D perimeter fence to reduce deer pressure on tree plantings. We’ve learned a lot or valuable lessons we are eager to share with others so they can save time and money if they choose to install one. Overall the fence is working well as a deterrent.

Key Learnings

- The Austree and SX-61 hybrids far outgrew other cultivars in year one

- Goat willow seems like a promising and desirable fodder species but is also slow growing initially and needs extra tender care to thrive

- Sourcing material locally (including having a friend who had cultivars grown out) was much more cost effective than purchasing plants, especially when considering the high mortality of the purchased stock. In a few hours we had more material that we knew what to do with, and cuttings were easily less than 10 cents a piece, vs .50 - 2.90 purchased. The biggest advantage of locally sourcing is the control one has to the timing of the activity to keep cuttings fresh and viable.

- Dormant hardwood cuttings are vulnerable to the variable spring thaw/freeze/warm weather conditions and that woodland nursery settings might buffer some of these effects and increase survival rates

- Overall, riparian areas are wonderful opportunities for developing fodder banks of wet tolerant species such as Willow. But, with the natural water dynamics of these zones, coupled with the increased variability from changing environmental conditions, means that development needs to be well timed, and even flexible, to plant out the space. Extra consideration to designing for water quality is foremost in importance, with the trees being a helpful follow up activity after the hydrology is addressed. Site B will be of particular interest, since we took advantage of the water line excavation and dug out substantial catches to slow water down and create berms for establishing the willow come Spring, 2024.

2024 Update

This season we have been able to successfully establish all three sites with randomized and rooted willow cuttings. We are happy to report this milestone to have the trees in the ground and growing.

Additionally, we acquired three additional species of larger diameter stakes from our technical advisor and decided to advantageously plant these along the edges but outside the “official” zone of the research. These varieties were recommended as being robust, producing ample vegetation, and growing quickly. One clear distinction is that we planted these in clusters of about a dozen “live stakes” spaced about 3 feet apart, using material that was around 1” in diameter. Given the wet winter that continued into spring, these stakes initially did very well, as did the plantings we established in Sites 2 & 3.

|

Bretensis |

Salix alba 'Britzensis' |

|

Gigantica |

Salix Aquatica Gigantea Korso |

|

Miyabeana |

Salix miyabeana |

Additional “clustered” willow added to the sites in 2024

While we had planted Site 1 in the previous Fall after removing the tarps, as noted last year the conditions were not favorable for planting the other two sites, because of excessive rain, the need for the excavated site to “rest” and settle, and the onset of colder than expected temps in November 2023. This provided a good opportunity to assess our progress and plan for a spring establishment of Sites B and C, respectively. This also gave us a second winter to test and assess the efficacy of the 3D fence before planting out more trees.

Further, we continued to reduce the variability of the plots, since it proved difficult to see how we would effectively mulch and maintain plantings with the items originally listed above (sawdust / wood chips / weed whack). It's safe to say that a huge learning from this project is the necessity to streamline activities for site prep, protection, and maintenance of plantings. We’ve landed on a helpful strategy to get trees established and maintain them cost-effectively, as follows:

1) Conduct site prep one season in advance, no matter the method.

2) Establish a 3D fence in advance of plantings, to encourage deer to re-route (more on this below) before establishing plantings.

3) Plant stakes that are ¾” or less in air prune beds for 1 - 2 seasons before planting. Stakes that are 1” or greater can be pointed at the bottom and driven in with a rubber mallet directly.

4) Immediately after planting, install a short tree tube and fiberglass stake to protect the base of the tree from burrowing rodents, and weed whacking. A taller stake also helps identify where the tree is if vegetation gets out of hand.

5) Weed whack strategically with timing, first at the end of the spring flush of growth (late May into early June) and then in late July/early August before anything gets too woody. Doing this at the right time drastically reduces the time it takes to complete the task.

The summary of plots has been updated below to reflect these learnings. Site C should be noted as having an additional activity that was unplanned when this project was conceived; we had a forestry mulcher onsite in the spring and decided to reduce much of the overgrown, dying, “invasive” buckthorn that was growing in the overstory, since it was easier to manage before planting. This provided an interesting and dense layer of shredded trees that acted much like a thick mulch, but proved more difficult to plant into so soon after. If we could have waited a year it would have been more amenable, likely.

|

Site A |

Site B |

Site C |

|

|

Site Prep |

Tarping April - August 2023 |

Excavation and berming, Nov 2023 |

Forest mulching Spring 2024 |

|

Planting Date |

November 2023 |

May 2024 |

May 2024 |

|

Protection |

Short tree tube and fiberglass stake, perimeter with 3D fence |

Short tree tube and fiberglass stake, perimeter with 3D fence |

Short tree tube and fiberglass stake, perimeter with 3D fence |

|

“Mulch” / maintenance |

Weed whack in late spring after flush, late July before stuff gets too woody |

Weed whack in late spring after flush, late July before stuff gets too woody |

Weed whack in late spring after flush, late July before stuff gets too woody |

Updated table with treatments to the three plots

Notes on the Deer Fence

While we are working on a longer article describing the installation and maintenance of a 3D style deer fence as part of the project outputs, in the meantime some important notes to share in reporting include:

1) Changing patterns of behavior: It has become clear through the project that a 3D fence is a deterrent, not a fortress that will keep deer out perfectly. It has become necessary, then, to keep apprised about the actual specific deer that are interacting with a site and know their habits may change over time. In consulting for the project, we leaned on our neighbor who hunts our land to help describe the normal patterns of movement, noted on the map below (ORANGE). Rather than attempt to keep the deer out, what our plan of the fence aimed to do was encourage the deer to go around the planting zone, in order words stick to the outskirts and perimeter rather than cut through our field.

2) Given the changing nature of individuals and herds, along with the effect of seasonality, it became necessary to therefore conduct routine inspections of the fence for evidence of deer, as well as testing and keeping the voltage up. Fallen limbs, uprooted stakes, and lines grounding out on saplings were all discovered during (almost) weekly check ups we conducted from May - October. We treated these as a chance to walk the land, in most cases taking less than one hour to complete.

3) When deer pressure was observed, action was taken to address it. In one instance, a corner of the fence (marked with a yellow arrow on the map) became an easy access for deer since they could get a running start and hop the fence. We addressed this by adding an additional loop of fence to the system (also in yellow) in October 2024 as well as felling a bunch of trees to discourage a good landing spot beyond the perimeter fence. This seems to have helped as the evidence of deer in the site was eliminated in the following weeks.

Still, even with these efforts we had some minor damage to willows planted, mostly the clustered “extra’ plantings we did. Yet since the deer may feel compelled to keep moving through the space, the damage was minor and we expect the trees to recover in the coming season.

All this to say, between the need to check on the fence to ensure it is operating at its top potential, along with the timing of vegetation growth to hit it before it become unwieldy, routine visits to the site and fence became necessary, and will continue to be so, until the majority of the willow is above browse height. Time will tell if this will happen in 2025, or beyond.

Notes on Measurements

In addition to the establishment goals for the project we set out to take measurement of growth, which we have done for trees in the nursery beds and after planting. Initially in the proposal we suggested monthly measurements but this proved too time consuming, and not particularly useful. So, we are shifting to simply annual measurements of growth (2023); from cutting to first year, and then for two seasons in the planting. (2024 and 2025). This should offer an average amongst the various cultivars that will provide ourselves and other farmers with good data to make future decisions.

Additionally, we have tracked the time and other costs associated with establishing willow in each of the three sites, which may prove useful when comparing the success of the different plantings. While the data won’t be completed and shared until our final report at the end of 2025, we can offer some initial observations of the plantings:

Generally, the trees planted in the excavated site (B) are growing faster and healthier than the other two sites. There is notable mortality and the trees are struggling most at site A, which may be a function of site prep (tarping), the timing of planting (Fall 2023), or some combination of these factors. The trees at site C seem to be doing initially pretty well.

We look forward to comparing the soils data, tree growth data, and observations from 2025 to see how these three sites compare at the end of the project.

Outputs

In addition to the field work described above, the following have been developed in 2024:

We built upon the initial database and literature review of willow and began outlining a guide to planting willow for Agroforestry, including information on collecting and care for cuttings, cultivar selection, site prep, and planting learned from this project.

We still have an evolving draft of the 3D fence article to finalize in the coming year and share as well towards the completion of the project.

Key Learnings

- Streamline the system: tree and fence maintenance is easy to fall down to the bottom of the list when so many other demands persist on the farm. It is necessary to find ways for these tasks to be achievable and routine.

- Size of willow matters: during propagation, staking material should be sorted for nursery growing versus direct planting into the field. Once growing, the race to get above browse height and become established helps reduce ongoing maintenance demands.

- Site prep is best a season ahead; When possible, the disturbance to a site takes time to occur, and time to recover from. Ideally a space of 6 - 12 months from site prep to planting seems best, at least within the context of the methods we have utilized so far.

- Deer fence needs vigilance: The 3D fence is a deterrent only if it's kept up, high voltage, and assessed for possible vulnerabilities on a routine (weekly?) basis.

- Excavation is doing best, overall; perhaps not surprising, the excavation site is proving to provide a really nice growing medium for the trees. It's not a stretch to imagine that hilling up two to four feet of rich soil would result in such positive outcomes.

2025 Results and Analysis

Growth in the three plots continued and we’re excited to share a collection of data, learnings, and reflections from this year and the project as a whole. In total, 79 trees were planted and 67 of them were still living by year 3. We were pleased to see an overall survival rate of 85% but also believe that the story goes beyond just “survivability” and that it is also important to look for “thrivability.”

Regarding thrivability, we are looking at how quickly trees get established and grow above herbivore browse height. To measure this, we analyzed the year 3 growth data against thresholds of 48 inches and 72 inches. While we found that measuring against 48 inches is a good general baseline, it still leaves trees vulnerable to herbivore browse. Because of this, we also analyzed the percentage of trees within each plot and species that grew to above 72 inches which is a much safer threshold when a farmer can consider removing tree fencing and protection.

We’ll begin with updates on our data collection and analysis and a selection of charts and graphs. To view the complete set of summary tables and line graphs, you can view our Tables and Charts document as an attachment to this report.

Below is our first summary table (Figure 1.1) from our final year 3 measurements. It summarizes the data across the 3 different test plots.

Analysis By Plots

As shown in the data from Figure 1.1, Plot B (Excavated and Mounded) supported the most growth with an average tree height of 114.8 inches. We believe that this can possibly be attributed to the large disturbance event during the excavation in the plot which helped limit competitive vegetation throughout the establishment period. Plot B also had consistent moisture levels which we believe also supported this site’s strong growth and establishment. Of the 27 trees that were planted in Plot B, only three of them had died by year 3. If we remove the three deaths from the data, the average height of the living trees in Plot B increased to 129.2 inches.

Plot B also featured the most amount of trees that grew to above 72 inches. As you’ll see in Figure 1.1, 77.78% of the trees planted in Plot B grew to above 72 inches by year 3. This suggests that if you have the ability to do more site preparation up front by excavating and mounding planting locations, then you may be able to remove deer fencing and overall protection earlier.

The plot with the next highest growth was Plot C (Swamp with topsoil spread) with an average tree height of 83.7 inches. This site also had consistent moisture as well as limited vegetative competition due to a large decomposing tree that was covering most of the soil. Out of the 27 trees that were planted, 6 of them died by year 3. This plot featured the lowest survival rate of 78% when compared to the survival rates of Plot A at 88% and Plot B at 89%. That said, if we remove the 6 deaths from the data, the average height of the living trees in Plot C increased to 105.2 inches. Because there was a lot of tree debris in this site, there was very little competitive vegetation to begin with and after planting we noticed that there still wasn’t a lot of understory growth. This condition, which was similar to the limited competitive vegetation in Plot B, may have contributed to the high growth rates in these top performing plots.

The plot with the lowest growth was Plot A (Tarped and woodchipped) with an average tree height of 65.1 inches. 25 trees were planted and by year three, 3 of them died. If we remove the 3 deaths from the data, the average height of the living trees in Plot A increased to 74 inches.

In Plot A, we also observed a noticeable difference in the percentage of trees that grew to above 48 inches but not 72 inches. This suggests that 48 inches was a meaningful threshold to measure growth against.

Initial Growth as an Indicator

In Plot B, we noticed there was the largest growth from year 1 to year 2 when compared to the other plots. Considering that Plot B was also the tallest growing plot, this may suggest that early fast growth from year 1 to year 2 could be a good indicator of the speed it would take for a tree to grow above browse height. This means that one could also infer that if a tree’s growth is not substantial from year 1 to year 2 in the field, then it will probably take several years for it to grow above a browse height of 72 inches.

Similarly, in all plots, and especially Plot C, if trees grew faster from year 1 to 2, it was typically a good indicator that strong growth would continue from year 2 to year 3

Now let’s move to Figure 1.2 and discuss the general findings across all of the 9 varieties of willow.

On Average Height by Variety

Among all the 9 varieties, we found that they naturally fell into three groups: Top performers (4 varieties), middle performers (3 varieties), and low performers (2 varieties)

The 4 varieties that grew to the tallest average height were Flame, Schwernii, Sx61, and Austree. The middle performers were Weeping, Osier, and Rubykins. The low performers included Curly and Goat.

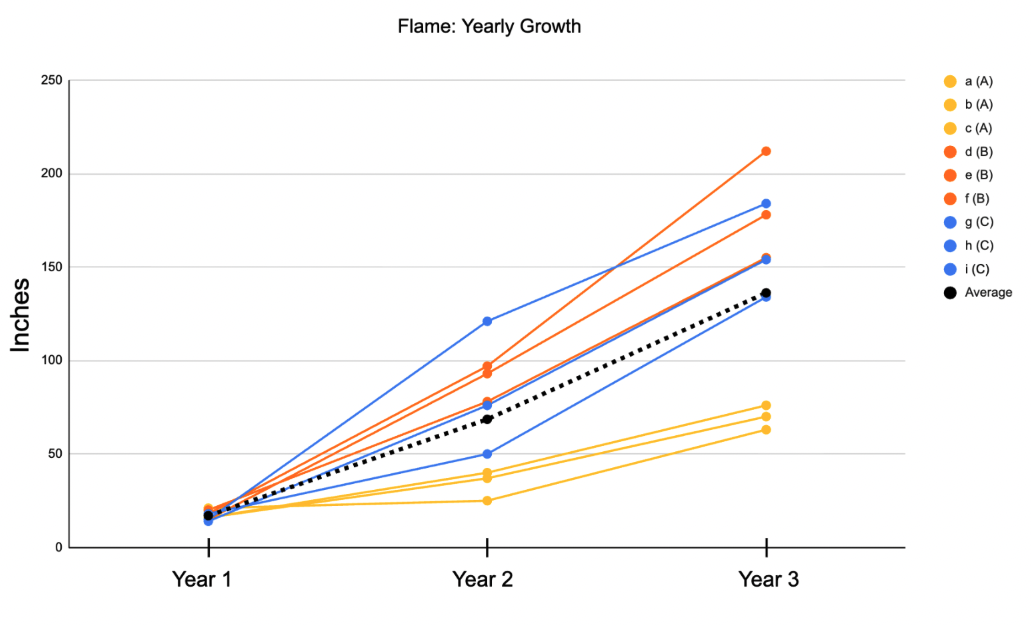

Flame and Schwernii as Top Performers

Flame, with 9 trees planted, suffered zero deaths and had the highest average growth by year 3 at 136.2 inches. It displayed particularly spectacular growth in Plots B and C with average growth heights of 181.7 inches and 157.3 inches, respectively.

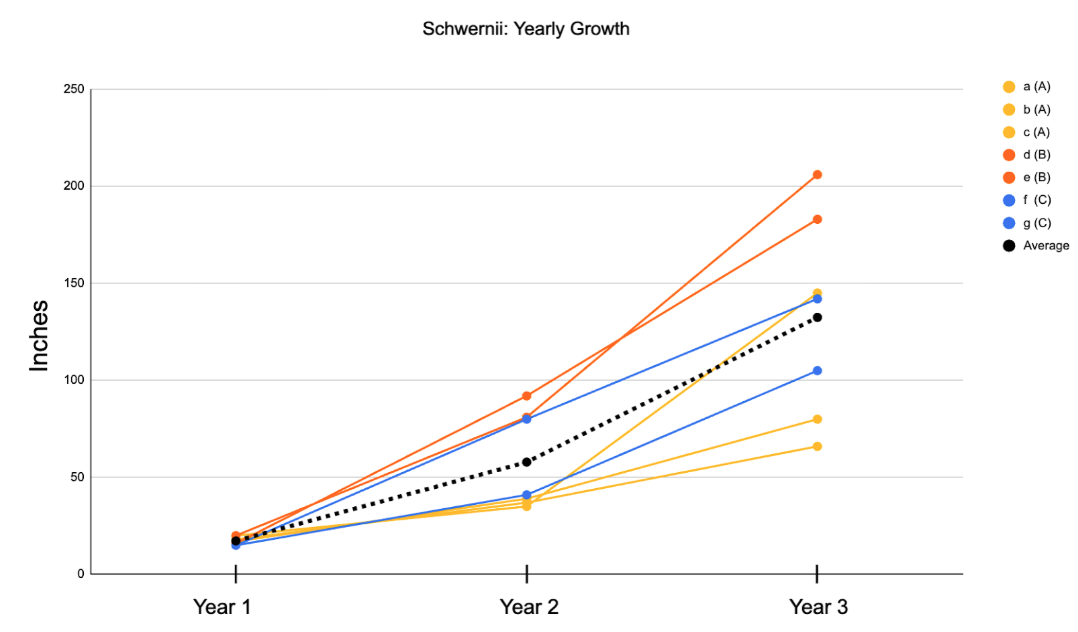

Below you will find four line charts for the top 4 tallest growing varieties. Across all of these line charts, you will see a black dotted line. This line indicates the average trend across this variety.

In general, across most varieties, we found that the orange line, representing Plot B, was typically above the average trend line and that the yellow line, representing Plot A, was typically below the average trend line. While this is not true for every variety, we did notice it as a general pattern.

Following closely behind Flame was Schwernii, with 7 trees planted and zero deaths by year 3. Schwernii also had remarkable growth with an average growth by year 3 at 132.4 inches. In Plot B, Schwernii’s growth was particularly extraordinary with the two trees planted in Plot B growing to 183 inches and 206 inches!

Sx61 (8 planted) and Austree (6 planted) also had noticeably strong growths with only 1 death each and year 3 average heights of 115.5 inches and 106.5 inches, respectively. If we remove each of the deaths for these varieties, the averages bump up to 132 inches for Sx61 and 127.8 inches for Austree.

The next 3 performing varieties, with respect to average growth in height by year 3, were Weeping, Osier, and Rubykins with average heights of 105.3 inches, 78.4 inches, and 75.1 inches respectively. These average heights, like the average heights listed above for Schwernii and Sx61, included any deaths that occurred by year 3. If we exclude the deaths from the average height data for Weeping, Osier, and Rubykins, the averages increased to 118.5, 85.5, and 120.2 inches, respectively.

In regards to this middle performing group, it is noteworthy to share a bit more about the results from the Rubykins variety. 8 Rubykins were planted and 3 of them died. Of the 5 that survived, their growth measurements were fairly distributed with year 3 heights of 40, 69, 126, 172, and 194 inches. This amounted to an average of 120.2 inches and the updated line chart shows this in Figure 9.3. Based on this small sample size, one could hypothesize that when Rubykins is happy with its growing conditions and environment, it has the potential to grow quickly. We noticed that it grew particularly well in Plot B which featured the mounded site preparation. That said, we also observed that Rubykins did not produce the largest or most dense leaf fodder, showing that even if a variety grows tall and fast, it isn’t necessarily the best choice for a tree-fodder application.

Finally, the lowest 2 performing varieties, with respect to average growth in height by year 3, were Curly and Goat with average heights of 52.9 inches and 28.7 inches, respectively. For both of these “low performers”, 9 varieties were planted and 2 died in each group. For the Goat variety, we measured three of the trees having lower heights measured in year 2 versus year 1. One of them died but two of them bounced back and continued putting on growth in year 3.

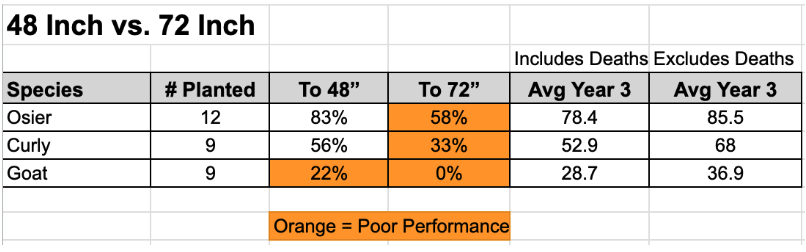

On Browse Height by Variety

One of the main goals of this research was to see which varieties, if any, would grow to above deer browse height by year 3. We used two height thresholds, 48 inches and 72 inches, to measure our data against. Of the 9 varieties, 8 of them had at least half of their trees grow to above 48 inches. Despite this promising result, it is important to note that deer browse would likely still persist at heights around 48 inches. When we looked at the higher threshold of 72 inches, we found that all of the varieties, except Goat, had at least 3 trees grow to above 72 inches and 5 of the varieties had at least 70% of trees grow to above 72 inches.

To get more specific, let’s go a bit deeper on a few of the varieties. For Flame, Schwernii, Sx61, and Austree, at least 78% of the trees made it above the 72 inch threshold by year 3. Among the 30 trees planted in these four top performers, 83% of them grew to above 72 inches by year 3.

For Sx61, we noticed solid height growth across all three plots! If we exclude the one death from Plot A, we found that the average height of its growth across Plot A, Plot B, and Plot C was 132.5, 129, and 136 inches, respectively. This may suggest it has the ability to thrive in a variety of settings and environments.

For Weeping, all of the surviving trees made it above 48 inches with all but one making it above 72 inches.

For Osier, the growth data was solid, but not excellent. This was a bit surprising given how well we’ve seen it thrive over the last 10 years on our farm. 92% (11 out of 12 planted) survived, and 83% made it above 48 inches. With that said, of the 11 survivors, only 7 of them grew to above 72 inches by year 3.

The lowest performing varieties were Curly and Goat. Of the 9 Curlys planted, 2 died, 5 grew to above 48 inches, and only 3 made it above 72 inches. For Goat, only 2 of the 9 trees planted grew to above the 48 inch threshold with 0 making it above 72 inches. Despite its low growth heights, we did observe that the leaf biomass on the Goat variety was denser than the other varieties. This suggests that Goat may still be a promising tree fodder source if the farmer has the time to wait for it to grow above browse height and the resources to protect from deer browse before then.

Overall, we found that 48 inches and 72 inches were useful thresholds to measure up against. When analyzing the growth results up against these thresholds, we noticed that Curly, Osier, and Goat had a 22%+ dropoff on how many trees grew to above 72 inches versus 48 inches.

Key Findings

- Plot B’s site preparation (excavating and mounding) produced the best results of any plot with the tallest average heights and highest percentage of trees growing above 72 inches. This suggests that if you have the ability to do more site preparation up front by excavating and mounding planting locations, then you may be able to remove deer fencing and overall protection earlier. The results from Plot B are perhaps not surprising given that we mounded up two to four feet of rich soil before planting

- The plot with the lowest growth was Plot A (tarped and woodchipped) with an average height by year 3 of 65.1 inches and 74 inches when excluding the 3 deaths

- Plot C had the most deaths as 6 of the 27 trees planted did not survive to year 3. That said, the ones that did survive grew to an average height of 105.2 inches by year 3. This places Plot C as the middle performing plot in terms of average growth height by year 3. Plot C performed similarly to Plot A (47.62%) regarding percentage of trees that grew to above the 72 inch browse height threshold by year 3 with 51.85%

- The hybrid varieties were some of the fastest growers, especially Flame, Schwernii, and Sx61

- Flame, Schwernii, Sx61, Austree, Weeping, were the top performers regarding average height and % above a browse height of 72 inches. Osier was also a steady grower but only 58% of the trees grew to above 72 inches by year 3.

- Flame, with 9 trees planted, suffered zero deaths and also had the highest average growth by year 3 at 136.2 inches

- Schwernii, with 7 trees planted, suffered zero deaths and had the second highest average growth by year 3 at 132.4 inches

- For Sx61, we noticed solid height growth across all three plots. This may suggest it has the ability to thrive in a variety of settings and environments

- Goat and Curly struggled to grow tall by year 3 but that doesn’t mean they are bad varieties for fodder production over a longer time period if the farmer can protect them until they grow to above browse height

- For Goat, only 2 of the 9 trees planted grew to above the 48 inch threshold with 0 making it above 72 inches

- Just because a tree grows fast, does necessarily mean it will be great for fodder, as it may have a low density and size of leaf material (i.e. Rubykins)

All tables and charts can be viewed here: Willow_-Tables-and-Charts

Our original questions to answer in this project were:

1.What is the cost and benefit of producing tree plant material on the farm vs purchasing it in?

2.What intensity of site preparation and tree protection is necessary for trees to thrive in a fodder block?

As previously noted, we were unable to answer #1 because the purchased material performed so poorly, perhaps due to quality issues but also the heavy frost events etc that stunted growth. We ultimately used materials from our own farm and local networks, from friends who were happy to trade material in exchange for management help. Perhaps this is the lesson moving forward - to source as local and cheaply as possible, which can result in more positive outcomes.

We originally planned to compare both Poplar and Willow varieties, but simplified the process along the way, choosing to focus on willow as it has more distinct and known varieties whereas poplar is mostly either wild unnamed variants or a small class of hybrids repeatedly used. We also simplified the original idea of having higher management variability for the three plots, choosing instead to focus on site prep as the main variable, and not vary the ways trees were protected, opting for the 3D fence as a site-wide strategy for protection. In the end, this ultimately helped show a stronger result, since more variables mean it would be hard to attribute success in any specific direction.

The results are quite clear regarding #2. Since all the cuttings were started in our nursery and planted out in the field, they had the same initial conditions, but were then placed in a spectrum of site prep efforts. The more the soil was distributed, the more initial growth occurred across the varieties. Some varieties performed well despite the conditions, but most responded to the higher levels of disturbance. Tarping didn't seem to provide enough of an edge for the willow to establish, while the forestry mulching, which resulting in a thick layer of organics and reduced competition from herbaceous plants, was decent. The mounding was clearly the most successful.

The summary table below ranks the 9 varieties in order from most to least vigorous according to year 3 data on survivability, percentage of trees that grew to above 48 inches, percentage of trees that grew to above 72 inches, and fodder/landscape value. The last quality is more based on our subjective observation, i.e. the varieties we saw having denser or larger leaf mass for fodder, the aesthetic value, etc.

|

Common Name |

Latin Name |

Growth Summary |

|

Flame |

Salix 'Flame' Firedance |

Thrived in all three plots with zero deaths and an average height in year 3 of 136.2 inches |

|

Schwerinii |

Salix schwerinii |

Zero deaths with 86% of trees growing to above 72 inches by year 3 |

|

SX-61 |

Salix sachalinensis |

Reliably thrived across all three plots with relatively dense foliage for a hybrid |

|

Austree |

Salix matsudana X Salix alba |

Strong growth with 83% of trees growing above 72 inches by year 3 |

|

Weeping |

Salix babylonica |

Despite having two deaths, all of the surviving trees grew to above 72 inches by year 3 |

|

Purple Osier |

Salix purpurea (Streamco) |

83% of the trees grew to above 48 inches and but only 58% grew above 72 inches by year 3. |

|

Rubykins |

Salix koriyanagi |

Suffered three deaths but at least one survivor grew fairly well in each of the three plots |

|

Curly |

Salix matsudana |

Slow growth with only 33% growing to 72 inches by year 3 |

|

Goat |

Salix caprea |

The slowest growing variety with only 22% growing above 48 inches by year 3. Despite slow growth, this variety features relatively large leaves, especially when compared to the hybrids. |

Interestingly, the flame which performed best is also a wild hybrid we collected here at Wellspring, which we have chosen to name along with other flame varieties, all generally considered part of Salix alba and with the characteristic red stems during dormancy. We are excited and surprised by this outcome, and it speaks to encourage other farmers to look to their own landscapes as a potential source for wild hybrid willow that may perform best. The tendency is to assume that the nurseries have the "best" stuff, but we forget the wisdom of plants, adapting to local landscapes, as a powerful selection tool. This doesn't mean every discovery leads to a superior varietal, but rather that the potential is certainly there.

All in all, the project was successful in establishing a healthy willow planting that will provide benefits to our wetlands and creek for decades to come, be a source of cut-and-carry fodder for the sheep, and an opportunity to continue evaluating the varieties and learning more. We plan to carry forward the most successful of these and make cuttings and rooted plants available via our nursery, as well as continue to add new willow varieties and trial their establishment success, sharing what we learn with others.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Agroforestry Field Day, 9/20/2024 was a facilitated tour and discussion of all agroforestry activities on the farm, but explicitly focused on the willow fodder trials. (16 participants)

Tree Nursery Intensive, 10/19/2024 hosted 16 farmers and toured the willow plantings and discussed methods for propagation.

Coppice Agroforestry Workshop, 11/9 and 11/10, hosted 13 farmers and toured the plantings.

Presentation at Savannah Institutes Perennial Farm Gathering, March 2025, over 80 present

Agroforestry Field Day, 6/26/2025 was a facilitated tour and discussion of all agroforestry activities on the farm, but we did discuss the willow fodder trials in detail. (17 participants)

Coppice Agroforestry Workshop on 11/1 and 11/2 where we hosted 15 farmers and toured the plantings as part of the class.

Instead of the full "guidebook" we originally planned, we have shifted to a series of articles that are attached to this report, and will be published in early 2026 to our substack as more effective way to distribute in digestable segments: https://wellspringforestfarm.substack.com/

These articles were collaborative efforts with apprentice Jonathan Dean and Jeff Piestrak of FLX Agroforestry, both who helped immensely in the success of the project, from establishment to research and writing up some really valuable resources.

Utilizing a 3D Fence to deter Deer for Agroforestry Tree Plantings by Steve Gabriel and Jonathan Dean

Wondrous Willow: One Farmer’s Journey Into an Unexpected Ally by Steve Gabriel

Basket-of-Options.docx : A practical guide to help farmers choose how, when, and why to use willow (Salix spp.) within agroforestry systems. Drawing on research and on-farm experience, it frames willow as a versatile “ally species” that can deliver multiple benefits—fodder, biomass, erosion control, runoff filtration, soil building, habitat, and craft/market opportunities—while acknowledging real tradeoffs and management challenges. The guide emphasizes an “options-by-context” approach, helping diversified farms match willow’s many functions to their specific land conditions, goals, and capacity.

Learning Outcomes

During our engagements with farmers and service providers, these themes and elements emerged:

-

Willow as a high-value agroforestry species

Farmers increasingly recognize willow as more than a fodder crop—valued for rapid establishment, coppicing ability, soil stabilization, water management, pollinator support, and resilience in wet or disturbed sites. -

Ecological function and production value can be stacked

Participants see that planting for ecological outcomes (erosion control, reduced competition, biodiversity, soil health) can directly support faster growth, higher survival, and more reliable fodder production rather than competing with farm productivity. -

Establishment strategy determines success

Farmers gain clarity that site preparation and protection intensity strongly influence tree performance, often more than variety choice alone, shaping both timelines and labor needs. -

Browse height thresholds guide management decisions

Using 48" and especially 72" as functional benchmarks helps farmers plan fencing, protection removal, and expectations around time to benefit. -

Early growth is a predictive signal

Strong growth from year 1 to year 2 builds confidence that trees will escape browse pressure sooner, enabling earlier intervention when growth is lagging. -

Variety choice depends on goals, not just speed

Farmers shift toward matching willow varieties to specific objectives—fast height gain, leaf density, site tolerance, or long-term fodder value—rather than assuming fastest growth equals best performance. -

Tree fodder systems are viable in the Northeast

Seeing multi-year data increases confidence that willow fodder blocks can be reliably established across farm contexts when ecological design and production goals are aligned.

Project Outcomes

As a result of this project, we have made clear changes in how we establish and evaluate tree fodder plantings on our farm, and we have seen meaningful benefits both in outcomes and confidence.

Most significantly, we have shifted toward more intentional site preparation and earlier decision-making during establishment. Seeing how excavated and mounded sites dramatically improved growth and reduced time to escape deer browse has changed how we allocate labor and materials up front. While this approach requires more effort early on, it reduces long-term protection needs and uncertainty, ultimately saving time and stress in later years.

We have also changed how we select willow varieties, moving away from assumptions based solely on survival or anecdotal performance. The data reinforced that hybrid willows such as Flame, Schwernii, and Sx61 can reliably reach browse-safe heights within three years under the right conditions, while slower-growing varieties like Goat or Curly may still be valuable for fodder but require longer protection and patience. This has improved our planting decisions and helped us better match varieties to specific farm goals.

Another important change has been adopting browse height thresholds (48” and 72”) and early growth rates as management tools. Rather than waiting several years to judge success, we now use year 1–2 growth as an indicator of whether a planting is on track or needs intervention. This has increased our confidence and reduced the feeling of “waiting and hoping” that often accompanies tree establishment.

Beyond production, this project strengthened our understanding that willow is a high-value agroforestry species that can deliver ecological and production benefits at the same time. Practices that improved ecological function—such as reducing competition, improving soil structure, and managing water—also led directly to better growth and more reliable fodder outcomes. This reinforced our belief that ecological stewardship and farm productivity are not trade-offs but can be intentionally designed to support one another.

Through field days and workshops, we have seen similar shifts among other farmers. Several participants commented that seeing three years of side-by-side data made tree fodder feel “doable” rather than experimental, and that the project helped clarify what level of investment is actually required to make trees succeed. One farmer shared that it “reset expectations in a good way” and made them more willing to invest early rather than repeatedly replant.

Overall, the project has improved our quality of life by reducing uncertainty, strengthening decision-making, and building confidence that well-designed tree fodder systems can work in the Northeast. It has also helped other farmers see willow not just as a conservation planting, but as a productive, multifunctional component of resilient farm systems.

Looking back, we feel the study’s overall approach was well aligned with the practical questions farmers face when trying to establish tree fodder systems, and that this applied, systems-based methodology was key to the project’s success. Rather than attempting to isolate a single variable, we intentionally tested combinations of site preparation, protection, and cultivar selection in real farm conditions, adapting to the realities of doing this from a farmer perspective and not being afraid to pivot as needed. This allowed us to generate results that are directly transferable to working farms, even though it introduced complexity in interpretation.

One of the most important methodological strengths was the use of replicated plots with contrasting site preparation strategies, combined with multi-year measurements. Tracking growth annually and analyzing both survival and functional outcomes (growth rate and browse height thresholds) provided a much clearer picture than survivability alone. The decision to evaluate performance against 48" and 72" browse height thresholds proved especially valuable, as it translated raw growth data into actionable management insights.

If we were to revise the methods, we would place greater emphasis on documenting labor hours, material costs, and protection intensity alongside growth metrics from the beginning. While growth outcomes were clear, better cost tracking would strengthen future economic comparisons between on-farm propagation versus purchased plant material, and between different levels of site preparation.

Overall, we did answer the primary questions we set out to study:

-

We demonstrated that site preparation intensity strongly influences establishment speed and time to escape browse height.

-

We identified which willow varieties are most likely to succeed within a three-year window under Northeast farm conditions.

-

We showed that ecological design choices can directly support production goals, rather than competing with them.

Based on these results, we plan to continue using and promoting willow as a multifunctional agroforestry species. The combination of fast establishment, coppicing potential, ecological benefits, and fodder value makes it a strong fit for diversified farms, especially where water management, soil stabilization, and resilience are priorities. Importantly, the project increased our confidence that success is repeatable when establishment is designed intentionally.

At the same time, the study highlighted the need for additional work. Future research should focus on economic analysis, longer-term coppice and fodder yields, and turn-key establishment guidelines that help farmers match site conditions, labor capacity, and goals to appropriate strategies. Additional regional trials would also help confirm how broadly these results apply across soil types and climates.