Progress report for FNE22-028

Project Information

- During season one cultivars from the CIMMYT seed bank will be identified, grown out in the field, and tested for viability. In other words whether they produce viable kernels.

- During season two the most promising varieties will be grown out and effort will be put into developing seed stock and determining the effect of different agricultural methods on production capacity. Local tortillerias and chefs will be given samples of maize to test against currently used corn.

- Results will be published and shared during each of the two seasons via press releases, interviews, and workshops for local farmers, with an emphasis on Latin American farmers. We will be in communication with our contacts the Intertribal Seed Keepers Network to ensure that we are transparent and following best practices with regard to indigenous maize germplasm and intellectual property.

For millennia populations in Latin America have depended on the maize tortilla as a staple source of nutrition. There are at least 60 cultivars in Mexico alone, and thousands of distinct varieties which have been selected and bred by indigenous populations for their agricultural, nutritional, and culinary properties. Seed coat hardness, starch to protein ratios, elasticity, and cohesion are a few characteristics1 that play a role in tortilla elaboration, characteristics that most maize varieties developed in the United States do not possess.

To accommodate, processors have invented work-arounds. One involves the expensive importation of traditional maize varieties. With historical transportation costs, and recently rising supply-chain issues, one northeast tortilla producer that was interviewed reported that using traditional imported corn varieties added thousands of dollars per pallet in shipping. Another option for tortilla production is to use domestic maize varieties. However, since these varieties were not bred specifically with tortillas in mind, often long lists of ingredients and binders must be used that render less desirable, but cheaply produced, shelf-stable tortillas, inadvertently sacrificing taste, nutrition, and authenticity in the process.

New York’s Hudson Valley has historically been our metro-area’s breadbasket and has recently seen a resurgence of interest in local small farm production. We also have a large and growing Latin American population. New York has the 3rd largest population of Mexican immigrants in the country, and the nearby county capital of Poughkeepsie has a particularly large stream of immigrants from Oaxaca, a great proportion involved in agricultural work. That is to say that there exists both a market for authentic tortillas and a population with the cultural heritage for production.

The main barrier for growing traditional Latin American heirloom tortilla maize varieties in the Hudson Valley is the difficulty in variety adaptation to our geography and climate. Principally, traditional maize from Latin America is photoperiod sensitive. This means that specific day length triggers vegetative and reproductive growth. At our northern latitudes, without similar daylengths and season duration, fertilization does not occur efficiently, and corn kernels do not form. When Native Americans brought the first maize varieties to northern latitudes, they bred out photo-period sensitivity for day-neutral characteristics. However, these populations did not specifically select for the other characteristics desirable for the elaboration of tortillas. Thus, most growers regarded growing traditional tortilla maize varieties as not viable in the northeast. However, in initial trials in the Hudson Valley, while most varieties did not work, several varieties of traditional maize for tortillas have shown promise.

This next phase of trials will attempt to build on those results by focusing on the cultivars of maize that showed promise. We will be working with those same lines and other varieties of the same cultivar, scaling up production, reproducing pure lines of seed, and evaluating enterprise potential. Results will be published to open opportunities for other local farmers, with a focus on Latin American producers. We will leverage our regional Latin American contacts in the local community, such as the “La Voz” magazine, to alert local producers of the potential and find ways to involve them in this initiative. We will also be in periodic communication with Technical Advisor Rebecca Yoshino's contacts at the Intertribal Seed Keepers Network to make sure that we are following best practices with regard to using indigenous maize germplasm and intellectual heritage and sharing results and seed in an equitable and transparent manner.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- - Technical Advisor (Educator)

Research

Season 1: Variety Trials (Summer, 2023)

The first season will be primarily dedicated to determining which of several heirloom maize varieties can realize a full life-cycle and produce viable kernels for future seasons within the climate of New York’s Hudson Valley. The selected varieties come from previous informal trials that I performed over two seasons with cultivars expressly used for the elaboration of tortillas in Mexico and Central America. These specimens were picked, with the help of a CIMYTT technician, to best match their native growing conditions with those of the northeast of United States. Since these varieties are likely photoperiod-sensitive, we looked for varieties from northern latitudes so that day-lengths would be more similar. We also accepted some varieties from other latitudes, but that require shorter growing seasons.

Of 16 heirloom maize varieties used expressly for the elaboration of tortillas in my possession, there were 11 varieties that showed high potential for further study, one variety that showed fair potential for further study, and 4 varieties that show no potential for further trials. The main factor determining which varieties should be eliminated is that flowering never occurred, or took place haphazardly, most likely due to photoperiod-sensitivity (long day-length of the Hudson Valley summer). The one variety that showed fair potential for further study demonstrated good ear and kernel development, however it was still quite green in November. The other 11 varieties showed good ear development and were fairly dry by November, when harvest generally occurs in this region. Unfortunately, there was not time to manually pollinate these specimens, and it can be assumed by logic and the presence of different colored kernels on the resulting ears that cross-pollination certainly occurred. Therefore, the seed produced from these trials should not be used for the purposes of this study (but perhaps could come in useful for future breeding efforts).

Building on this informally collected data, we will request more seed of the 12 chosen varieties from CIMYTT for our formal trials in 2023. We will hand-pollinate 50 individuals of each variety to avoid cross-pollination (We are not worried about inbreeding during season one. We will request more seed from CIMYTT in season two to achieve a minimum germplasm diversity of 200 parent plants). Hand-pollination will follow established protocols using tassel and sprout bags.3 This will take a great amount of observation and time, since it will be hard to estimate the exact timing of sprout appearance and pollen dropping, and the fact that some maize plants will reach up to 15 ft tall and the use of a ladder will be necessary to secure and collect tassel bags

We will plant these 12 varieties in our trial fields following the most common protocols of the region so that a real assessment can be made as to whether they would fit into a commercial setting. A soil test will be performed, and the recommended addition of organic fertilizer will proceed planting. Direct-seeding will occur the week of May 15, 2023. Spacing will be at 12” between each plant (due to the large size of these heirloom varieties that easily reach 15 ft tall) and 30” between rows. Irrigation and hand-weeding with wheel-hoes and stirrup hoes will take place regularly depending on field conditions. This data will be recorded throughout the trial.

Data collection will take place over the course of the season. Some of this data can actually be compared with the CIMYTT database information for these same varieties. This can help to determine if these varieties are reaching their full potential in the Hudson Valley. Data collection will include:

-Planting Date

-Harvest Date

-Days to silking

-Ear height

-Number of ears

-Rows of kernels

-Mature plant height

-Percent of lodging

-Ear size

-Percentage of grain fill (kernels fully formed)

-Kernel color

-Kernel moisture level at harvest

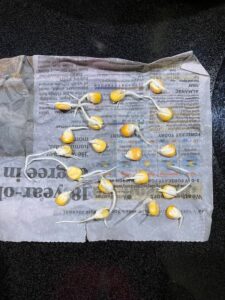

-Germination test of harvested kernels

-A Lab performed corn analysis (% Moisture, % Crude

Protein, % Crude Fiber, & % Starch)

Data and conclusions will be shared in a season report through local media, symposium, interviews, and workshops at regional Farm Education institutions, such as Glynwood, Stone Barns, HV Farm Hub, and Four Corners Community Farm. Special attention will be given to reaching Latin American farmers in the region.

Season 2 – Creating Seed Stock, Measuring Cultural Practices, and Determining Processing Quality (2024)

Season two will follow similar protocols to season one, however we will reduce the number of maize varieties and focus only on those that demonstrated the best results in Season 1. This will principally be based on the varieties ability to produce full ears within the constraints of our season and with minimal lodging.

We will request additional seed samples from CIMYTT to reach the 200 individual germplasm threshold. Plants will again be hand-pollinated to ensure purity of lines.

During this season we will measure varied cultural practices, focusing on planting density. We will collect the same data-points as in season one, but compare them with regard to different plant spacings at 8”, 10”, and 12”. A change in planting density could potentially have significant influence on the economical viability for regional farmers growing these varieties.

Finally, we will recruit several culinary experts in the region who produce their own tortillas in restaurant settings (Stone Barns in Tarrytown, Tortilleria Nixtamal in Queens, Tortilleria Allison in Poughkeepsie, etc.) to evaluate the culinary properties of these varieties. Variables will include flavor, elasticity, and cohesive properties.

Data and conclusions will be shared in a season report through local media, symposium, interviews, and workshops at regional Farm Education institutions, such as Glynwood, Stone Barns, HV Farm Hub, and Four Corners Community Farm. Special attention will be given to reaching Latin American farmers in the region. We will be in regular communication with the Intertribal Seed Keepers Network in order to be transparent and respect indigenous maize germplasm and intellectual property.

Season 1: Year 2023 (Crop Failure)

Unfortunately we had a severe drought this season:

https://www.dec.ny.gov/lands/5017.html

Our soils are particularly well drained Haven soils, and we simply did not have the water available to irrigate this corn trial plot adequately without adversely effecting other farm cash crops.

This season's trial is considered a crop failure. Based on previous years´ experience, it was obvious that the corn plants were stressed, growth was slowed, full sizes were not reached, and thus pollination and ear development was either delayed or not carried out at all.

It did not make sense to collect data this year. I got permission from the SARE grant team to delay the trials one season. I will be making modifications to my farm-wide irrigation capacity, and hopefully we will not run into a similar situation next season.

Season 2: 2023

The same protocols were used in Season 2 as in Season 1. This season was basically a re-start due to the previous year's severe drought and crop failure. Many of the original varieties of corn from Season 1 could no longer be acquired, however similar varieties with comparable attributes were requested and obtained from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

19 varieties were planted in two 50 rows per variety at 1 ft radial spacing in beds 6 feet on center. Each spacing was double-planted by hand with 2 seeds a few inches apart (to insure high germination) and later thinned to one plant per space. Seed was planted at a depth of between 1 and 2 inches.

The field was cultivated by hand using stirrup hoes once at about 6" of growth, a second time at about 2" growth that included hilling, and a final time at about 18" growth to incorporate a cover crop of broadcasted inoculated red clover seed.

Over the course of the summer season measurements and photos were taken as often as possible: date of first tassel appearance and date of first silk appearance.

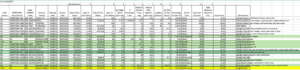

Between October 24th and 28th, 5 stalks of each corn variety were cut and measured. 5 ears of corn were harvest, shucked, and dried in our greenhouse for several days during the data collection. Data was tallied and summed up on the attached excel spreadsheet: Days to tassle, days to silk, avg. height of ear on corn stalk, avg. total height of stalk, avg. numbers of harvestable ears, percentage of grain fill on ear, avg. length of ear, avg. number of rows of kernels, germination rate, lodging percentage, stalk dryness observations, and any other notable observations.

Season 1: 2022

We will resume trials in 2023 with better irrigation capabilities to eliminate the risk of drought induced stunting like we had in 2022.

Season 2: 2023

Data points were weighted and final ranking was made. Based on these Season 2 results, seven varieties of corn (highlighted in green) were chosen for further trials, plus the control group (highlighted in yellow), in Season 3, 2024.

In Season 3 care will be taken in manual pollination to avoid crossing and create the beginnings of a seed bank for each corn variety. One critical consideration for determining whether any of these varieties are economically viable will be whether the kernel moisture is dry enough to be stored in rudimentary conditions. I will cut stalks in late October. A few samples of grain for each variety will go straight to a germination test to see if they are viable. However sheaves of stalks will also be made allowing for the grain to dry further in the field until after several hard frosts. Subsequent germination tests and moisture tests will be performed to see if grain is truly storable.