Final report for FNE24-078

Project Information

The purpose of this project was to determine whether deliberately designed combinations of beneficial microbes and insects could form persistent, self-sustaining biological control systems in greenhouse production, rather than requiring repeated, isolated inputs.

We conducted a two-phase study. In Phase I, we ran a series of rapid, small-scale experiments testing microbial soil amendments, pathogen suppression, plant growth responses, and early predator–prey setups under real greenhouse conditions to identify constraints and failure modes. In Phase II, we focused on three larger, interpretable ecosystem designs: (i) establishing a continuous aphid insectary to support predatory insects, (ii) a controlled enclosure trial testing the beetle Rhyzobius lophanthae against soft scale on soursop trees, and (iii) molecular analyses linking cultivation practices to below-ground biology using long-read rhizosphere metagenomics (figs) and root-associated proteomics following microbial amendment (olives).

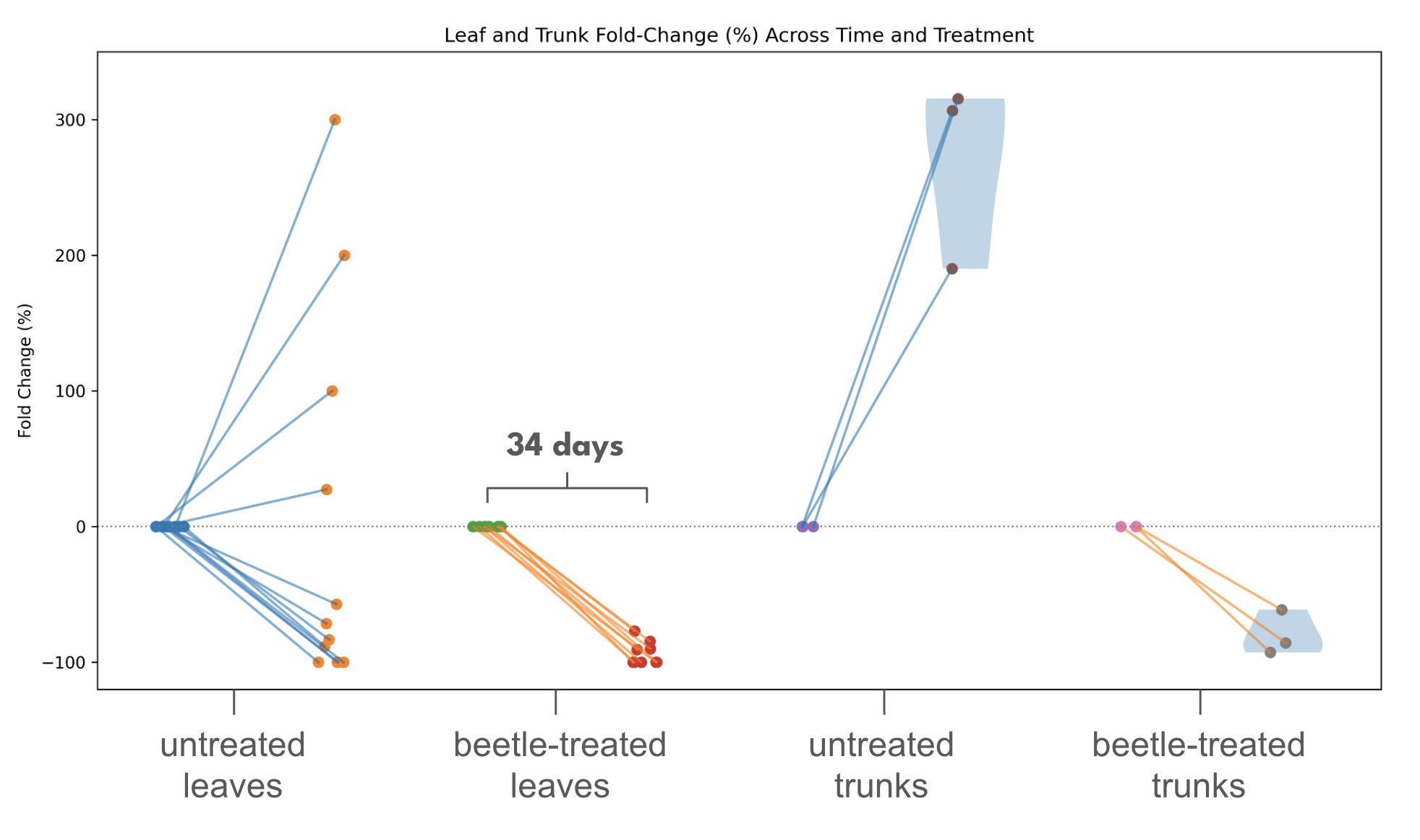

Results showed that predator persistence in vented greenhouses depends strongly on prey logistics: through iterative scouting and multiple release strategies, we found that introducing cereal-grass banker plants supplied by a continuous aphid insectary was associated with longer observable persistence of lacewings and parasitoids than release-only approaches previously attempted under the same greenhouse conditions. In controlled mesh chambers, Rhyzobius lophanthae reduced visible scale abundance on soursop trees by approximately 80% over 34 days, while scale abundance increased by ~200% in untreated controls. Long-read Nanopore sequencing of fig rhizosphere soils (18–19 Gbps per sample) revealed differences in dominant assembled contigs between potted and raised-bed systems, with raised beds showing a more distributed taxonomic signal. In olives, root-associated proteomics showed modest but coherent shifts in protein localization and metabolic pathways following microbial amendment over a 142-day growing period.

Overall, the project demonstrated that building self-sustaining biological control systems requires treating prey production, enclosure design, and organism viability as core infrastructure rather than secondary considerations. While not all microbial products or early interventions produced measurable plant growth benefits, the work yielded practical, replicable methods for predator persistence and controlled biocontrol testing that are compatible with farm operations.

Outreach included on-farm demonstrations, greenhouse tours, webinars, and a hands-on farmers market exhibit featuring live predator–prey systems. These activities reached local growers, farm customers, and the broader community, providing accessible education on biological control, banker systems, and alternatives to chemical pest management.

Our project is designed to achieve several objectives:

- Experiment with Three Major Ecosystem Designs: Test three unique ecosystems to identify the most beneficial synergies for plant growth, disease, and pest control. These will be tested sequentially to benefit from insights gained after each experiment. For each iteration, we will compare an untreated control against an experimental ecosystem, sending each for root exudate analysis. Along with root exudate analysis, we will also study insect populations to assess the designed ecosystems’ abilities to promote their recycling.

- Experiment with Many Minor Ecosystem Designs: This objective is the same as the previous, except these experiments will not be analyzed for root exudates, thus saving significant costs, allowing for rapid iteration.

- Standardize Ecosystem Design Methodologies: Standardize methods for designing and deploying self-sustaining ecosystems that maintain their health and productivity, even in the absence of immediate pest threats.

Through this project, we anticipate not only advancing our scientific understanding of soil microbiology and plant-microbe interactions but also delivering practical, tangible benefits to farming practices. Our goal is to pave the way for more sustainable, efficient, and productive agriculture, rooted in a deep understanding of the soil's living tapestry.

Problem:

Microgreens, herbs, and subtropical plants are a booming business worth billions and loved for their colors, flavors and nutrition. But they're under threat from tiny pests and diseases that can wipe out crops and profits. Most farms use chemical sprays to keep these pests away, but these aren't great for the planet or for people who prefer eating organic. There are some natural pest-fighting products out there, but they don't stick around long enough to keep protecting the plants. They're like a band-aid rather than a cure. And while some smart solutions use good bugs to fight the bad ones, they often don't stay for the long haul, dying from starvation or flying away, leaving plants vulnerable again.

Solution:

Our idea is like building a mini nature reserve right where we grow our microgreens and plants. We're not just focusing on getting rid of pests; we're creating an entire neighborhood of helpful creatures and good bacteria that take care of the plants from the ground up. Think of it as a tiny, bustling city under the leaves where everyone has a job to do, from tiny worms that make the soil rich for growing, to good bacteria that help plants absorb food better and grow stronger.

Here’s the clever part: by bringing together the right mix of these tiny helpers, we make a system that is self-sufficient. Like a well-tended garden, it can take care of itself. This means once we set it up, it keeps going, protecting and feeding the plants without us having to add more helpers later. This is good news for the farmer who won’t have to keep buying new products, and great for the environment because it's all natural.

For example, let’s say fungus gnats are the problem. We can introduce friendly nematodes that hunt down the gnat larvae. We'll also bring in parasitic fungi (the good kind) that take out the gnats' food source without harming the microgreens and plants. These fungi can also help the plants by extending their roots, which means the plants can reach more food and water in the soil. But how do the nematodes persist when their food’s gone? Well, we want to learn, through trial and error, how to add species as a secondary food source, that won’t harm the plant, so the nematodes can keep growing strong even when they’ve eaten all the pests in the environment.

But we’re not stopping there. We’ll add in a team of Bacillus bacteria, which are like tiny farmers themselves, helping to recycle nutrients and make the soil even better for plant growth. These bacteria also help keep the bad fungi away by living in the soil and roots, making it hard for the bad guys to take hold again. And because all these helpers are already approved by the EPA, we know they’re safe to use and won’t harm the environment.

In short, we're not just solving a pest problem; we're learning how to set-up a natural, self-sustaining system that’s a win-win for everyone: healthier plants, happier farmers, and a happier planet.

We Grow Microgreens, LLC, is a small commercial urban farm. We are owned and operated by urban growers, Lisa Evans and Tim Smith, specializing in growing highly nutritious microgreens, edible flowers, tea leaves, medicinal plants, and herbs using sustainable and regenerative growing practices. The farm started in 2015 out of the owners’ backyard in Roslindale and expanded to an approximately one acre plot in Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts in 2019 where it successfully farms today.

The farm operates out of a 4600 square foot greenhouse and two 25 x 40 high tunnels and 173 raised garden beds. What makes We Grow Microgreens, LLC unique is that our plants are grown predominantly with natural sunlight. Our sunshine-grown microgreens, herbs, and plants are available to consumers within hours of harvest. Our greenhouse is energy and water-conserving, with an energy-efficient condensing boiler to heat the flood benches, insulated foundation, translucent solar panels, shade curtain, roof vents and a roof rainwater collection system for watering the microgreens, herbs, and plants.

Additionally, the farm aims to educate youth, consumers and chefs on the nutritional value of microgreens, flowers, and medicinal plants through educational programs. It prides itself on empowering local youth to actively participate in local agriculture through jobs and educational training.

Our products can be found at the Roslindale, Natick, Mattapan, Wayland, Newton farmer’s markets and at our farmstand. Additionally, restaurants seek-out their produce. The farm accepts City of Boston coupons, WIC/HIP and SNAP which are programs for food insecure people.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor (Educator and Researcher)

- - Producer (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

- (Educator)

Research

Project Leader: Tim Smith

Tim Smith is a graduate of Oberlin College and Boston College Law School. He taught in the Boston and Newton Public Schools for a decade. Prior to teaching, he worked at John Hancock Insurance Company on a class action lawsuit. He has worked on the business since January 2015 when his passion for growing plants took over his house. Tim completed a training with Nelson and Pade on Aquaponics, but ultimately microgreens grown in soil with sunshine and tropical plants became his passion. Currently, he is a co-owner of We Grow Microgreens, LLC a small urban farm in the City of Boston. He won second place at the Boston Flower Show for an Olive and Jade tree, and second place for the Shade Category of the City of Boston’s Garden contest. He and Lisa received official recognition from the Boston City Council for Recognition of the creation and leadership of Hyde Park’s first Urban Farm through the development of remedies and cultivation of partnerships for sustainable green food production.

Contributing authors:

- Christopher Kenyon, Earthbarrier

- Mikayla von Ehrenkrook, Earthbarrier, Northeastern University Co-op Student

- Elson Ortiz, We Grow Microgreens

- Meredith Bultmeyer, Northeastern University Co-op Student

- Michael Lembck, Earthbarrier

- Ana Varela, Northeastern University Co-op Student

- Annalin Griffel, Northeastern University Co-op Student

- Lisa Evans, We Grow Microgreens

- Tim Smith, We Grow Microgreens

All insect drawings by courtesy of Annalin Griffel

Phase I: Minor Ecological Experiments

Microbial product compositions:

Great White (4g):

7 species of ectomycorrizal fungi:

- Pisolithus tinctorius.........751,500 propagules

- Rhizopagan luteolus.............20,876 propagules

- Rhizopagan fulvigleba..........20,876 propagules

- Rhizopagan villosullus..........20,876 propagules

- Rhizopagan amylopogon......20,876 propagules

- Scleroderma citrinum............20,876 propagules

- Scleroderma cepa...................20,876 propagules

9 species of endomycorrhizal fungi:

- Glomus aggregatrum...................332 propagules

- Glomus intraradices....................332 propagules

- Glomus mosseae..........................332 propagules

- Glomus etunicatum.....................332 propagules

- Glomus clarum.............................44 propagules

- Glomus monosporum.................44 propagules

- Glomus deserticola......................44 propagules

- Paraglomus brasilianum.............44 propagules

- Gigaspora margarita....................44 propagules

2 species of Trichoderma fungi:

- Trichoderma koningii.........751,500 propagules

- Trichoderma harzianum......501,000 propagules

13 species of bacteria:

- Azot0bacter chroococcum………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Bacillus subtilis……………………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Bacillus licheniformis……………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Bacillus azotoformans……………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Bacillus megaterium………………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Bacillus coagulens…………………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Bacillus pumilis……………………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Bacillus amyloliquefaciens……………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Paenibacillus polymyxa…………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Paenibacillus durum……………………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae……………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Pseudomonas aureofaciens…………2.1×10⁶ CFU

- Pseudomonas fluorescens……………2.1×10⁶ CFU

Mikro-Myco (4g):

4 species of endomycorrhizal fungi (260 CFU):

- Glomus intraradices..................260 CFU

- Glomus mosseae......................260 CFU

- Glomus aggregatum..................260 CFU

- Glomus etunicatum....................260 CFU

7 species of ectomycorrhizal fungi (872,000 CFU):

- Rhizopogon villosulus.............124,572 CFU

- Rhizopogon luteolus...............124,572 CFU

- Rhizopogon amylopogon........124,572 CFU

- Rhizopogon fulvigleba.............124,572 CFU

- Pisolithus tinctorius................ 124,572 CFU

- Scleroderma cepa...................124,572 CFU

- Scleroderma citrinum..............124,572 CFU

4 species of rhizobacteria (1.6×10⁹ CFU):

- Bacillus licheniformis................4×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus pumilis.........................4×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus subtilis.........................4×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus megaterium.................4×10⁸ CFU

3 species of Trichoderma fungi (3.0×10⁶ CFU):

- Trichoderma harzianum...............106 CFU

- Trichoderma viride.......................106 CFU

- Trichoderma longibrachiatum......106 CFU

Mikro-Root (4g):

2 species of Trichoderma fungi:

- Trichoderma harzianum.....................8×10⁷ CFU

- Trichoderma viride.............................8×10⁷ CFU

Plant Thrive (4g):

- Bacillus subtilis…………………………7×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus amyloliquefaciens……………7×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus licheniformis……………………7×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus megaterium……………………7×10⁸ CFU

- Pseudomonas fluorescens……………6×10⁸ CFU

- Pseudomonas putida……………………6×10⁸ CFU

- Azospirillum amazonense………………5×10⁸ CFU

- Azospirillum lipoferum…………………5×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus firmus…………………………2.4×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus pumilus………………………2.4×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus azotoformans………………2.4×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus coagulans……………………2.4×10⁸ CFU

- Bacillus pasteurii………………………2.4×10⁸ CFU

- Geobacillus stearothermophilus……2.4×10⁸ CFU

- Pseudomonas aureofaciens…………6×10⁷ CFU

- Streptomyces coelicolor………………6×10⁷ CFU

- Streptomyces lydicus……………………6×10⁷ CFU

- Streptomyces griseus……………………6×10⁷ CFU

- Trichoderma reesei………………………6×10⁷ CFU

- Trichoderma hamatum…………………6×10⁷ CFU

- Trichoderma harzianum………………6×10⁷ CFU

- Rhizophagus intraradices………………28 spores

Experimental methods:

Experiment 1:

Wheat grass was studied to see if we could prevent infection of a naturally occurring greenhouse fungus by introduction of a fungal biocontrol agent. This was accomplished using 83 mg of Great White microbial mix because it contains a collection of Trichoderma species that are known to suppress other pest fungi via parasitism. We collected the pathogenic fungi from a contaminated wheat grass specimen, suspended in a water solution, blended the solution for 10 seconds in a standard nutribullet, and counted the resulting spore suspension with a hemacytometer. Fresh cultures of wheat grass were seeded in soil and the experiment was constructed thus:

- Wheat grass alone

- Wheat grass inoculated with fungus

- Wheat grass inoculated with fungus and Great White microbial mix

- Wheat grass with Great White microbial mix

Wheat grass was then allowed to grow for 7 days first in a germination chamber and then open in the greenhouse under the grow tables.

We found contamination in all conditions indicating some external source of fungal inoculation and insufficient control by the Great White.

Experiment 2:

To follow up on our previous wheat grass experiment, we wanted to see where our contamination was coming from. We sterilized soil and water in an autoclave and surface sterilized wheat grass seeds with a 3% bleach 0.1% tween-20 solution (30 minutes of shaking at 37C). We then repeated the previous experiment with the following conditions:

We performed a 2x2x2x2x2 factorial experiment with the following factors:

- wheat grass +/- surface sterilization

- soil +/- autoclaved sterilization

- water +/- autoclaved sterilization

- inoculation with fungus +/-

- inoculation with Great White microbial mix +/-

We continued to find contamination in all conditions indicating some external source of fungal inoculation and insufficient control by the Great White.

We planned to then repeat the experiment with increased amounts of Great White microbial mix to see if we could improve the control but we ran out of time as the weather was getting too hot for the wheat grass to grow in the greenhouse.

Experiment 3:

Two hydroponics shelves were prepared using captured rainwater where 40 L of rainwater in each condition was supplemented with Part A and Part B nutrient salts per supplier's instructions. Control condition was left as is and experimental conditions were further supplemented with Mikro-Myco according to packaging instructions. The shelves were then run with water flowing overnight to ensure complete mixing of nutrients and inoculants. It was noted the next day that the Mikro-Myco inoculant formed a foamy consistency that was distributed across all of the shelves of the inoculated tower. Asian green seedlings were then planted in each well of each shelf of each tower and the plants were grown on a light:dark cycle of 16:8. The plants were left to grow for 21 days.

After 21 days of growth, no observable differences in plant height were observed.

Experiment 4:

Mikro-Root and Great White each contain Trichoderma fungi. We were curious whether these fungi could accelerate germination and how it related it to various other bacterial and fungal microbes present, in addition, in Great White. We therefore designed an experiment that attempted to separate out the effects of these microbes by designing experimental conditions that accounted for the relative contribution of Trichoderma fungi in these products.

Treatments

- Control: Radish grown in BX Pro-Mix growing medium

- Treatment 1: Radish grown in BX Pro-Mix growing medium mixed with 2.05 grams of Mikro-Root

- Treatment 2: Radish grown in BX Pro-Mix growing medium mixed with 6.21 grams of Great White

- Treatment 3: Radish grown in BX Pro-Mix growing medium mixed with 1 gram of Mikro-Root and 3.16 grams of Great White

Steps

- BX Pro-Mix growing medium moistened with warm water

- Mixed approximately a tray of BX Pro-Mix growing medium with varying amounts of Great White and Mikro-Root.

- Spread soil into trays and watered

- Measured radish seeds for each treatment

- Control: 31.510 g

- Treatment 1: 31.220 g

- Treatment 2: 31 g radish seeds

- Treatment 3: 31.115 g radish seeds

- Seeded trays and put into germination chamber

Results: No visual differences between germination levels and growth of the microgreens were observed.

Experiment 5:

We were interested in whether the results we were seeing were due to insufficient time for the fungus to colonize the soilless medium before plants were seeded. We therefore compared T0 (incubation time = 0 days) to T7 (incubation time = 7 days) allowing the fungus to colonize our soilless medium.

10/7/24

T7 treatments mixed with approximately two trays worth of Pro-Mix BX growing medium in buckets

- Control: Peat-based Pro-Mix

- Great white: 4 grams

- Mikro-Root: 4 grams

- Mikro-Myco: 4 grams

- Plant thrive: 4 grams

10/8/24

T7 Buckets shaken

10/9/24

T7 Buckets shaken

10/12/24

T7 Buckets shaken

10/15/24

T0 treatments mixed approximately two trays worth of Pro-Mix growing medium in buckets

- Control: Peat-based Pro-Mix

- Great white: 4 grams

- Mikro-Root: 4 grams

- Mikro-Myco: 4 grams

- Plant thrive: 4 grams

Setup:

- Pea shoots were soaked (to induce germination)

- Treatment Pro-Mix conditions were spread in labeled trays and watered

- Soaked pea shoots were seeded onto treated Pro-Mix

- Pea shoots were then covered with fresh untreated Pro-Mix

- Trays were placed under the table with a tray on top to germinate

10/21/24

Removed pea shoots from under the table and watered. No observable difference in germination rates between trays.

10/25/24

Measured trays:

- Picked 10 shoots from each tray at random

- Measured shoots from the seed to the top of the leaf

- No observable differences measured

Experiment 6:

Our grant proposal intended to investigate the conditions necessary to create self-sustaining cycles of predatory insects. We predicted one of our initial obstacles to be the food sources of those predators and the food sources of the prey. In response to this obstacle, we chose to focus on greenhouse farmers most prevalent pest, aphids.

- Collected kale leaves without aphids and with aphids from outdoor garden beds

- Using a disassembled pen casing, pressed out kale leaf discs with both ends of the pen to create two different disc sizes. Pressed out 30 small and 30 large discs.

- Relocated aphids on full sized kale leaves to leaf discs. Placed discs in small white cereal bowls 50% filled with tap water

- In one bowl, 15 small discs and 15 large discs were added with 11 "small" aphids. These aphids are younger, and have molted less times.

- The other bowl contains 15 small and 15 large discs with 9 "large' aphids

- Wrapped the bowls in clear cling wrap to avoid spread of pest

- Moved filled bowls to empty shelves inside greenhouse and outside of direct sunlight

11/25/24

Treatments

- Control: Pea shoots grown in sand

- GW 4: Pea shoots grown in a mixture of sand and a solution of 4 grams of GW and water

- GW 24: Pea shoots grown in a mixture of sand and a solution of 24 grams of GW and water

Setup

- Soaked pea shoots in warm water

- Drained pea shoots

- Created two solutions of Great White mixed with warm water

- 4 grams of Great White

- 24 grams of Great White

- Mixed solutions with sand in trays

- Saturated sand with water

- Measured pea shoots for 3 trays

- 0.265 kg (265 g) of pea shoots per treatment

- Seeded pea shoots and covered in a thin layer of sand

- Put trays under the table with a tray on top of the sand

12/3/24

Pea shoots removed from under the table. Visual notes on trays:

- Control: Growing the best by far. Sand is the driest in this tray.

- GW 4: Growing the worst. Inconsistent germination and lower height. Sand is the wettest in this tray.

- GW 24: Has more germination than GW4, but less than Control. Sand moisture is somewhere between Control and GW4.

Is the inconsistent germination in the GW 4 & GW 24 because of GW, sand moisture, or both? Did GW make the sand retain moisture. Did GW inhibit growth, causing less pea shoots to take up water? Or were the trays watered inconsistently, and levels of moisture inhibited growth.

12/10/24

Results:

By day 8 (12/3/24), visual differences were apparent among treatments. The control tray showed the most uniform germination and the greatest shoot height, while the 4 g Great White treatment showed the poorest germination and lowest height. The 24 g Great White treatment was intermediate (better than 4 g but below the control). Notably, substrate moisture differed across treatments: the control tray appeared driest, the 4 g Great White tray wettest, and the 24 g tray intermediate.

At harvest (12/10/24), pooled shoot biomass (drained and weighed) was 0.915 kg (Control), 0.730 kg (GW 4), and 0.950 kg (GW 24). Overall, in this trial, Great White application was associated with reduced performance at 4 g and no clear biomass penalty at 24 g, while moisture differences across trays remained a likely confound affecting germination and early growth. Worth repeating in the future.

Experiment 8:

Rearing Aphidius ervi

Objective

- Understanding population cycles between aphids and wasps brings us closer to unraveling the necessary conditions for sustainable predator environments.

Background

- Managing pest populations is ultimately the priority in our farm and testing how effective 250 wasps are in managing aphids answers a question relevant to real farmers.

- We purchased 250 Aphidius ervi wasps and released them on 17 pepper plants to fight an ongoing aphid infestation. Since then we have observed the establishment of a population of wasps that has cycled tightly with the aphid populations.

Methods

- Location and Setup

- Location: Flood tables in Greenhouse

- 17 pepper plants

- Plants between 1-3 feet

- 250 wasps were spread evenly among 17 plants

- Location: Flood tables in Greenhouse

- Data Collection

- Individual aphids were counted periodically by hand

- As populations were discovered, branches were labeled with hole-punched notecard paper. Notecards occasionally fell, leading to gaps in the data. Branches were relabeled uniquely to capture trends. For example, Branch 1 may suddenly stop receiving data inputs but the same branch data may be represented by a new branch label 45.

Results:

We were successful in rearing a colony of wasps on our aphid-infested pepper plants. These wasps produced a continuous supply of aphid mummies and achieved a steady-state population with the aphids. We observed noticeable season-to-season suppression of aphids greenhouse-wide relative to previous seasons while the plants served as a banker plants for the greenhouse. Scaling this setup would have likely been successful in terms of aphid management, but the process would require continuous cultivation of clean pepper plants, as the pepper plants' health was the raw resource that was consumed that allowed for the greenhouse-wide protection. These pepper plants succumbed to infestation and were discarded the following season. This is curious in that the wasps, while protecting the greenhouse from aphid pressure, never wiped out the aphids populations on the peppers themselves -- suggesting some mechanism that maintained the population steady-state in an almost Lotka-Volterra–like manner.

Healthy Aphid Counter - Google Sheets

Phase II: Major Ecological Experiments

Aphid insectary system:

To create a reliable, on-farm prey reservoir to support predators (especially lacewing larvae), we established a continuous aphid production system (“aphid insectary”) based on cereal grasses. We purchased bird cherry–oat aphids (Rhopalosiphum padi) from IPM Labs, shipped on aphid-infested barley, along with additional barley seed intended for clean re-seeding. To prevent contamination by parasitoid wasps and other greenhouse insects, the starter colony and host plants were maintained inside a mesh butterfly rearing chamber.

Upon arrival, the infested barley was allowed to grow and the aphid population was permitted to expand. After ~4 days, aphid density had increased substantially (approximately doubling). In parallel, we germinated fresh barley seed; once the new barley had emerged, it was introduced into the same mesh chamber to provide fresh host tissue and expand colony carrying capacity. Aphids dispersed onto the new barley over the following ~3 days until colonization was broadly distributed across the fresh seedlings.

As barley seed became limiting, we transitioned the colony onto wheat grass, which performed equivalently as a host plant and simplified ongoing production. To keep the colony vigorous and avoid over-crowding or host depletion, we maintained the system by “splitting” aphids onto fresh grass on a regular schedule, generally no more aggressive than a 1:2 transfer (i.e., using one mature, infested tray to seed no more than two new trays). Fresh wheat grass trays were started approximately one week before planned transfer so they were at an appropriate growth stage when introduced.

This workflow produced reliably infested banker-plant components approximately weekly. Once deployed into the greenhouse, these aphid-infested trays were quickly located and consumed by beneficial insects, supporting the central premise that maintaining predator populations is as much a prey-logistics problem as a predator-release problem.

Rhyzobius chamber trial:

To evaluate the effectiveness of Rhyzobius lophanthae as a biological control agent for soft scale on soursop (Annona muricata), we constructed two enclosed grow chambers using fine plant mesh netting typically used for bird exclusion. Each chamber enclosed approximately 10 cubic feet of volume (dimensions ~2 ft × 1 ft × 5 ft) and was oriented vertically to accommodate tree height. The mesh allowed airflow and light penetration while preventing beetle escape and external insect entry.

Six soursop trees of similar size and visible baseline scale infestation were selected. Three trees were placed into each chamber. One chamber received 500 adult Rhyzobius lophanthae (treatment), while the second chamber served as a beetle-free control. All trees were watered to saturation at the start of the trial.

Baseline scale counts were performed immediately prior to beetle introduction. For each tree, scale insects were counted using a standardized protocol:

(1) a systematic trunk survey, moving from the base upward and counting all visible scale along the trunk and major branches, and

(2) six randomly selected leaves, on which all visible scale insects were counted.

This yielded seven measurements per tree (one trunk count and six leaf counts).

Trees remained enclosed for 34 days, after which chambers were opened and scale populations were re-counted using the identical counting protocol. Pre- and post-trial counts were compared within and between chambers to assess changes in scale abundance attributable to beetle presence.

Olive root-associated proteomics experiment:

Experimental design and plant material

Twelve olive trees were used in this experiment, comprising two cultivars: Ascolana (n = 6) and Mission (n = 6). Trees were grown in pots under greenhouse conditions prior to the start of the experiment. The study was designed as a paired control–treatment comparison, with cultivar representation balanced across treatment groups.

Baseline (time zero) root sampling — June 26

On June 26, baseline (“time zero”) root samples were collected prior to any microbial treatment. All twelve trees were removed from their pots, and loose soil was shaken off into two separate buckets. Each bucket contained soil from three Ascolana and three Mission trees to maintain cultivar balance. Two additional scoops of fresh soilless medium were added to each bucket.

Roots were thoroughly rinsed with hose water to remove residual soil. Following cleaning, root segments were collected for proteomics analysis. For each sample, root cuttings were pooled across six trees (three Ascolana, three Mission), with approximately 100 mg of root tissue per tree, yielding ~600 mg total root mass per sample. Root segments were cut to approximately equal size so that each tree contributed evenly to the pooled proteome profile.

Two pooled samples were prepared at time zero:

- Control baseline sample

- Treatment baseline sample

At this stage, both samples were biologically identical and served as pre-treatment controls.

Root cuttings were briefly rinsed in sterile water, packed into 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes, and immediately flash-frozen in the liquid phase of liquid nitrogen. Samples were held submerged for approximately three hours due to logistical constraints and then transferred to the laboratory and stored at –60 °C.

Personnel present for baseline sampling: Chris Kenyon, Hannah Glaser.

Soil amendment and treatment initiation

Immediately following baseline sampling, microbial amendments were applied to initiate the treatment phase. One soil bucket received 3 oz of Plant Thrive and 2 oz of Mikro-Myco, which were mixed thoroughly by hand. The second bucket received no microbial additions and served as the untreated control.

Olive trees were repotted into their original pots using either treated or untreated soil, establishing experimental groups. This repotting marked Day 0 of treatment.

Maintenance during treatment period

Trees were maintained outdoors for the duration of the experiment. Trees were watered as needed with plain water. On August 1st, the treatment group was reinoculated with ~5 grams Mikro-Myco. Care was taken to normalize total watering volume across groups and minimize cross-contamination throughout.

Final root sampling — October 6

On October 6, a second round of root sampling was performed using the same protocol as the baseline collection. Trees were removed from pots, roots were cleaned of soil, and root segments were collected and pooled across cultivars and treatment groups using identical mass targets (~600 mg pooled root tissue per sample). Samples were rinsed in sterile water, packed into microcentrifuge tubes, and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to storage at –60 °C.

Personnel present for final sampling: Chris Kenyon, Annalin Griffel.

Proteomic analysis

Frozen root samples from both timepoints were shipped on dry ice to Lifeasible for root-associated proteomic analysis. Lifeasible performed protein extraction, identification, and quantitative analysis using their standard proteomics workflow. Returned datasets were used for comparative analysis between baseline and post-treatment samples, as well as between treated and untreated conditions.

Fig rhizosphere soil metagenomics – materials and methods:

Experimental design and soil sampling

To compare microbial community composition between potted fig trees and raised-bed fig trees, soil samples were collected from both cultivation systems. For each condition, a single 50 mL conical tube was filled with soil sampled from the fig rhizosphere.

In both cases, surface soil was first removed to avoid recently disturbed or aerated material. Soil was then collected from deeper layers proximal to the fig root system, targeting the active rhizosphere rather than bulk topsoil. Sampling locations were chosen immediately adjacent to visible root structures.

Sample preservation and sequencing

Each 50 mL soil sample was placed directly into liquid nitrogen and flash-frozen in the conical tube without further processing. Frozen samples were then shipped on dry ice to CD Genomics for Oxford Nanopore long-read metagenomic sequencing.

Bioinformatic processing and taxonomic analysis

Returned sequencing data were processed using a long-read–focused analysis pipeline. Reads were filtered to retain sequences ≥20 kilobases in length, enriching for high-information content reads suitable for assembly.

Filtered reads were assembled using metaFlye with parameters optimized for long-read metagenomic assembly. From the resulting assembly, the top 50 contigs (by size) were selected for taxonomic classification.

These contigs were analyzed using Kraken2 with the standard reference database. Taxonomic assignments were aggregated at the genus level, and the top 20 genera were reported for each soil condition. These genus-level profiles were used to compare dominant contributors to soil microbial biodiversity between potted and raised-bed fig cultivation systems.

Phase I:

Phase I focused on rapid, parallel exploration of biological control, microbial amendments, and cultivation variables to identify practical constraints, failure modes, and promising directions for deeper investigation. Rather than optimizing a single intervention, we intentionally tested a wide range of systems under real greenhouse conditions to determine which approaches were robust enough to justify further investment in Phase II.

Wheat Grass Pathogen Suppression:

We found during humid and hot Summer growing conditions contamination from a local greenhouse fungus.

- Tested whether fungal biocontrol agents (e.g., Trichoderma spp. in Great White microbial mix) could suppress greenhouse fungal contamination.

- Conditions: Wheat grass alone, inoculated with fungus, inoculated with fungus and Great White microbial mix, and inoculated with Great White microbial mix alone.

- Process: Fungus was blended and quantified with a hemocytometer; treatments were applied to sterilized soil and monitored for 7 days under greenhouse conditions.

- Results: Contamination persisted across all conditions, indicating external fungal sources and no observable control by Great White microbial mix.

Source Tracking of Fungal Contamination:

- Sterilized soilless medium, water, and wheat grass seeds (surface-sterilized with 3% bleach and 0.1% Tween-20).

- Conducted a 2x2x2x2x2 factorial experiment to isolate contamination sources.

- Results: Contamination persisted, suggesting external inoculation sources and insufficient biocontrol by Great White.

Hydroponic Trials:

- Asian greens were grown in two hydroponic systems using rainwater with and without Mikro-Myco supplementation.

- Observations: Mikro-Myco condition formed foam across inoculated shelves. Plant growth was monitored for 21 days under controlled light-dark cycles.

- Mikro-Myco–treated plants seemed to have a growth advantage over untreated plants in early growth stages (~3-7 days), but differences were washed out after continued growing (21 days).

Radish Microgreens in Pro-Mix BX:

- Tested different microbial supplements (Great White, Mikro-Root, and combinations) on radish germination and growth.

- Results: No visual differences in germination or growth between treatments.

Pea Shoots in Sand and Great White:

- Evaluated the effect of increasing concentrations of Great White on pea shoot germination and growth in sand.

- Process: Pea shoots were grown in trays with sand supplemented with 0 g, 4 g, or 24 g of Great White.

- Results: Control conditions outperformed treatments with Great White. Higher moisture retention in treated sand may have inhibited germination. Root length was mildly divergent among conditions but counterintuitive, with both control (0g) and strongly treated (24g) out-performing weakly treated (4g). This experiment should be repeated in the future.

Aphid Rearing and Biocontrol with Aphidius ervi:

- Investigated population cycles of aphids and Aphidius ervi on pepper plants.

- Process: Released 250 wasps onto 17 pepper plants and monitored aphid populations weekly, using labeled branches for consistent tracking.

- Results: Population dynamics demonstrated the need for stable aphid prey populations to sustain predator cycles. Overall, aphid populations held steady, suggesting insufficient wasp populations to achieve complete control, but interestingly, a stable predator-prey dynamic may be achievable over sustained periods even in greenhouses.

- We found the peppers became banker plants and survived the Winter even under sustained aphid burden. We suspect the wasps were beneficial here though in that without the wasps the aphid populations may have exploded, killing the pepper plants much earlier than observed. Global greenhouse aphid pressure was also observed to be reduced relative to previous seasons.

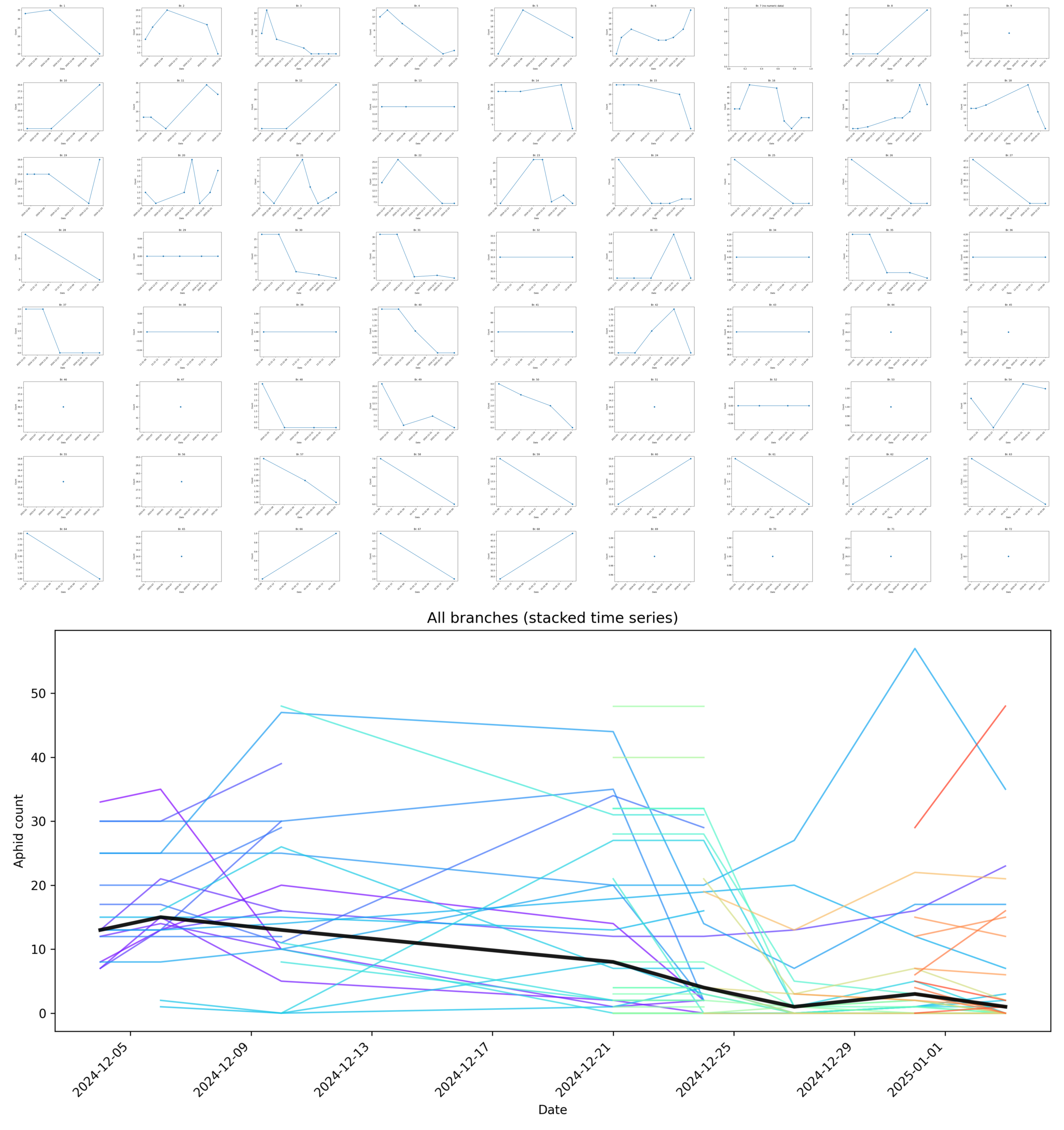

- A sample of the season's population dynamics were measured over a month across 72 branches by tracking healthy aphids (Figure 1). Aphid mummies were disqualified. The populations of both Aphidius ervi wasps and Myzus persicae green peach aphids persisted through the rest of the Winter.

Figure 1. Branch-level aphid dynamics under Aphidius ervi biocontrol. Top panel: Individual branch-level time series (“sparklines”) for live aphid counts measured repeatedly over approximately one month across 72 branches. Each mini-plot represents a single branch, showing raw counts of live aphids only; aphid mummies (parasitized individuals) were explicitly excluded from counts. Missing values correspond to late addition of new branches to the tracked set and/or physical loss of a branch tag. Bottom panel: All branch-level time series overlaid in a single plot (colored by branch), with a bold black line indicating the per-date median aphid count across all branches. Despite substantial heterogeneity in early aphid abundance across branches, median aphid counts decline and remain suppressed over time, rather than exhibiting unchecked exponential growth. Together, these data provide a branch-resolved proxy for the coupled dynamics of the aphid population and the parasitoid Aphidius ervi population. Because mummified aphids were excluded, reductions in live aphid counts reflect both direct aphid mortality and successful parasitoid activity. The absence of a sustained exponential increase in aphid abundance across branches is consistent with effective population-level suppression by A. ervi under the experimental conditions.

Figure 1. Branch-level aphid dynamics under Aphidius ervi biocontrol. Top panel: Individual branch-level time series (“sparklines”) for live aphid counts measured repeatedly over approximately one month across 72 branches. Each mini-plot represents a single branch, showing raw counts of live aphids only; aphid mummies (parasitized individuals) were explicitly excluded from counts. Missing values correspond to late addition of new branches to the tracked set and/or physical loss of a branch tag. Bottom panel: All branch-level time series overlaid in a single plot (colored by branch), with a bold black line indicating the per-date median aphid count across all branches. Despite substantial heterogeneity in early aphid abundance across branches, median aphid counts decline and remain suppressed over time, rather than exhibiting unchecked exponential growth. Together, these data provide a branch-resolved proxy for the coupled dynamics of the aphid population and the parasitoid Aphidius ervi population. Because mummified aphids were excluded, reductions in live aphid counts reflect both direct aphid mortality and successful parasitoid activity. The absence of a sustained exponential increase in aphid abundance across branches is consistent with effective population-level suppression by A. ervi under the experimental conditions.

Scale Biocontrol using Aphytis melinus:

- Investigated scale populations on guanabana trees and their response to release of a market-available scale biocontrol. Aphytis melinus is known to be an ectoparasite of certain scale species.

- Process: Released 200,000 Aphytis melinus on guanabana trees to combat scale infestation.

- Results: Scale populations did not decline. Aphytis melinus was observed briefly following release (2–3 days) but has since escaped observation, likely due to cold temperatures and an improper ecological fit.

Data Collection:

Plant Growth Assessment:

- Measuring biomass using precision milligram scales.

- Evaluating root and leaf health macro- and microscopically.

Upcoming Molecular and Genetic Analyses:

- Sequencing soil DNA using Nanopore technology to map microbial population dynamics.

- Sending plant samples to Lifeasible for root-associated proteomics profiling.

Challenges and Adjustments:

Insect Attrition:

- Observed higher-than-expected mortality in early insect releases. Addressed this by integrating secondary food sources, especially for lacewings.

Weather Impact:

- Temperature fluctuations in the greenhouse prompted adjustments in experimental direction.

Quality of Microbial Products:

In December 2024 we learned of an interesting research article comprising a meta-analysis of soil amendment microbial products suggesting that mycorrhiza products largely are not of the quality they are advertised as. This may be due to extended shelf time or poor mixing of the product in packaging. Under light microscopy, we did not consistently observe structures we expected given label claims; although viability and composition may vary across batches and shelf time. This finding prompted us to reinterpret parts of our earlier work: some effects we initially attributed to “mycorrhizae” may instead be driven by non-mycorrhizal members of the product, including bacterial taxa such as Bacillus spp. Going forward, we are incorporating routine microscopy-based quality checks when opening new microbial product batches to separate label claims from verified biological inputs and strengthen experimental controls.

Phase II:

Ecological release and establishment program. Over the course of Phase II, our work shifted from isolated interventions toward the deliberate construction of ecological infrastructure within working greenhouse environments. The starting point for this phase was an establishment-focused program: rather than asking whether individual releases could produce short-term suppression of specific pests, we asked whether repeated introductions of compatible beneficial arthropods could persist under day-to-day production conditions and begin functioning as part of the resident predator community, where long-lived plants can act as both pest reservoirs and potential anchors for beneficial populations. To explore this question, we conducted large-scale releases directly into the greenhouse. Over this phase we released 5,000 green lacewing larvae, 2,000 brown lacewing eggs, and 500 brown lacewing adults, alongside 2,000 Phytoseiulus persimilis predatory mites targeting spider mites. We also released 500 Rhyzobius lophanthae adults and 250 Cryptolaemus montrouzieri adults, both predators of scale insects and mealybugs on perennial tropical plants. Releases were spatially distributed across plantings to encourage dispersal and habitat matching rather than forced localization. Routine scouting following releases yielded several informative observations. Cryptolaemus montrouzieri adults were readily observable on multiple scouting days after release, an outcome we attribute primarily to their relatively large body size and high visual detectability rather than definitive evidence of long-term establishment. Brown lacewings were also observed in the greenhouse over a month after last release, suggesting at least transient persistence. However, because brown lacewings are sometimes slow to hatch, it cannot be confirmed that their populations are yet successfully recycling. For smaller and well-camouflaged beneficials, including predatory mites, lacewing larvae, and brown lacewings in particular, detectability during routine scouting was inherently limited, and absence of observation should not be interpreted as absence of persistence.

Aphid production and prey-base infrastructure for predator persistence. Early Phase II work made clear that direct release alone is insufficient to ensure persistence of beneficial arthropods in vented, high-temperature greenhouse systems. In particular, predators introduced into an otherwise prey-limited environment are unlikely to remain resident, even if they are well matched to target pests. To address this constraint, we established a small, modular aphid-production system. Our initial proof-of-concept using leaf-disc aphid cultures demonstrated that aphids could be reared off intact plants in semi-controlled conditions, but also revealed practical shortcomings for sustained use, including drowning risk from condensation and fragility of the small-disc format. We therefore replaced this approach with a more robust “aphid factory” system operated in a garage space. In this system, wheat grass is continuously seeded, aphid colonies are allowed to establish and expand, and infested trays are periodically rotated into the greenhouse. Rather than supporting a single predator species, these banker plants function as generalized prey patches that can be accessed by multiple predatory taxa present in the system, including lacewings and other generalist arthropods. To reduce the risk of unintended crop infestation, we selected the bird cherry–oat aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi), which is attractive to many predators but has low affinity for most greenhouse crops aside from cereals. This trophic infrastructure directly supports the broader establishment program described above by shifting the system from one that relies on repeated, isolated releases and natural pest populations exclusively to one that actively supports predator persistence as a property of the greenhouse itself. It also provides a scalable, farmer-friendly template for integrating ecological support structures into routine greenhouse operations without specialized containment or continuous external inputs.

Scale suppression on soursop using Rhyzobius lophanthae. Additionally, we have continued our work on scale insect control on our soursop trees. As mentioned, earlier in the grant period we released ~200,000 Aphytis melinus wasps as they are known to be a general parasitoid of scale, but we did not observe meaningful suppression of the scale identified on our soursop, which we have tentatively identified as Coccus longulus. Under this grant, we therefore shifted our attention to Rhyzobius lophanthae, a beetle commonly referred to as the purple scale predator. Our first step was a simple release of 500 Rhyzobius adults into the central greenhouse, with the twin goals of long-term establishment and a hopeful reduction in scale burden as seen during routine scouting. On release we observed direct predator–prey interactions, confirming that the beetles readily locate and consume scale on our trees. However, given the size and vented-roof architecture of the 4,600-square-foot greenhouse, we recognized that beetles would disperse widely or escape, and that the lack of a true control would make any change in scale pressure hard to interpret. To address this, we ran a controlled chamber experiment using two mesh-wrapped grow chambers (~10 cubic feet each). We selected six potted soursop trees of similar height and baseline infestation, performed an initial scale census (juveniles and adults visible on trunks/branches), and placed three trees in each chamber. We watered all trees to saturation to minimize moisture-related confounding. We then released 500 Rhyzobius adults into the treatment chamber and kept the second chamber beetle-free as a control. After 34 days, we repeated the same scale-count method. Results were encouraging: the treatment group showed an approximate 80% reduction in visible scale relative to baseline, while the untreated control chamber showed an approximate 200% increase in scale burden over the same period (Figure 2). Beyond the biological result, this chamber method provided a practical template for replicated biocontrol trials on high-value trees that fits daily farm operations.

Figure 2. The effects of the beneficial beetle Rhyzobius lophanthae on the scale insect tentatively identified as Coccus longulus

Additionally, this experiment has given us a practical template for running replicated biocontrol trials on high-value trees in a way that is compatible with day-to-day farm operations.

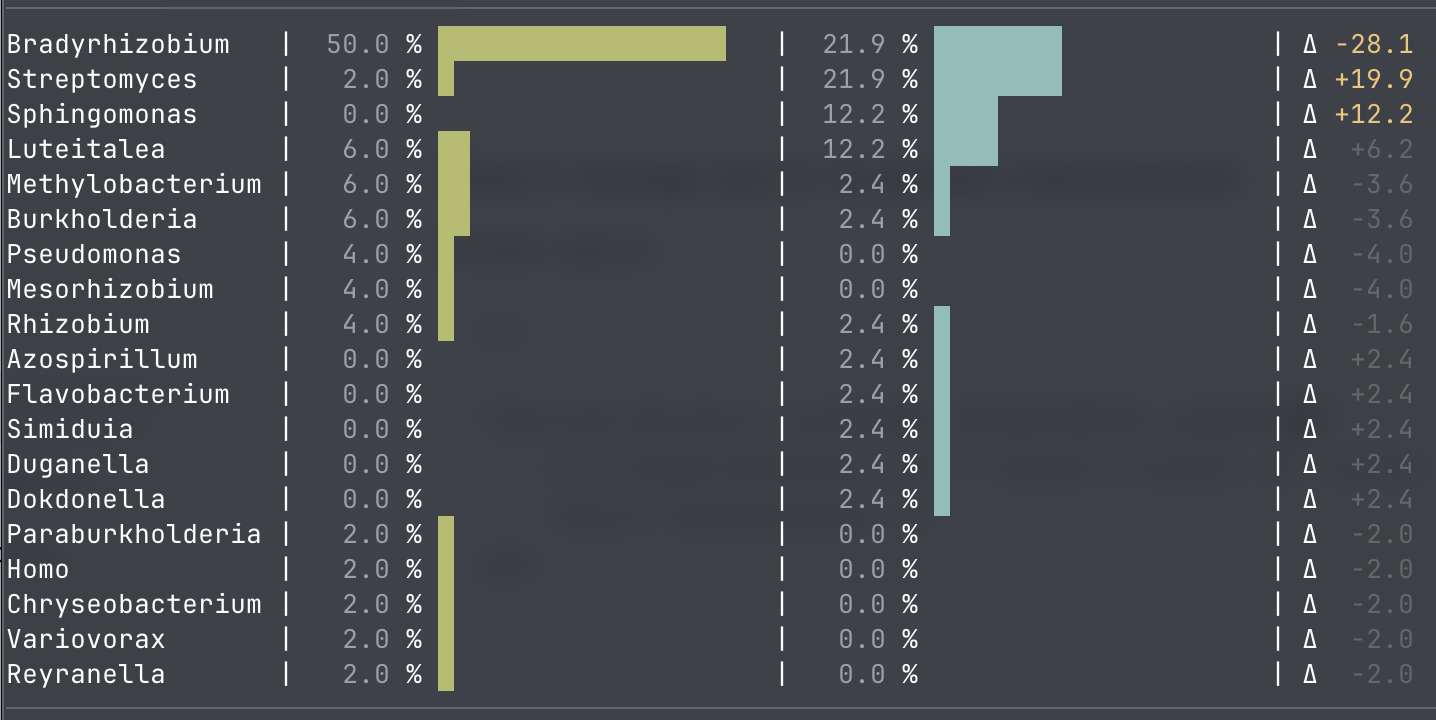

Molecular and chemical datasets linking practice → measurable biology. To connect farm-scale ecology to measurable belowground biology, we generated two large datasets. For figs (Ficus carica), we collected rhizosphere soil from a thriving raised-bed tree (“bed”) and a neutrally-productive potted tree (“pot”) and performed Oxford Nanopore long-read metagenomic sequencing. The pot and bed datasets were 18.32 Gb and 19.32 Gb, respectively, from which we generated long-fragment-enriched subsets by filtering for reads ≥20 kb. We assembled these long-read subsets using metaFlye and extracted the longest contigs as a metagenomic landscape readout, then assigned taxonomy to these contigs using Kraken2 against the 10/15/2025 RefSeq “standard” database build. At this conservative resolution (not a formal community composition estimate), we observed mild differences between cultivation contexts: the pot assembly’s top contigs were heavily dominated by Bradyrhizobium (25/50 contigs; 50%), while the raised-bed top contigs were more distributed, with prominent Bradyrhizobium (9/41; 21.95%) alongside Streptomyces (9/41; 21.95%), Sphingomonas (5/41; 12.20%), and Luteitalea (5/41; 12.20%) (Figure 3). These results are presented as an initial “snapshot” indicating that open, soil-connected beds and isolated containerized systems may differ materially in their assembly-derived metagenomic signal, motivating deeper follow-up (deeper sequencing, genomic binning, annotation, and functional emphasis on nutrient cycling and plant-associated traits).

Figure 3. Genus assignment distribution among the longest assembled contigs (top-20 contig snapshot), pot (left) vs raised-bed (right).

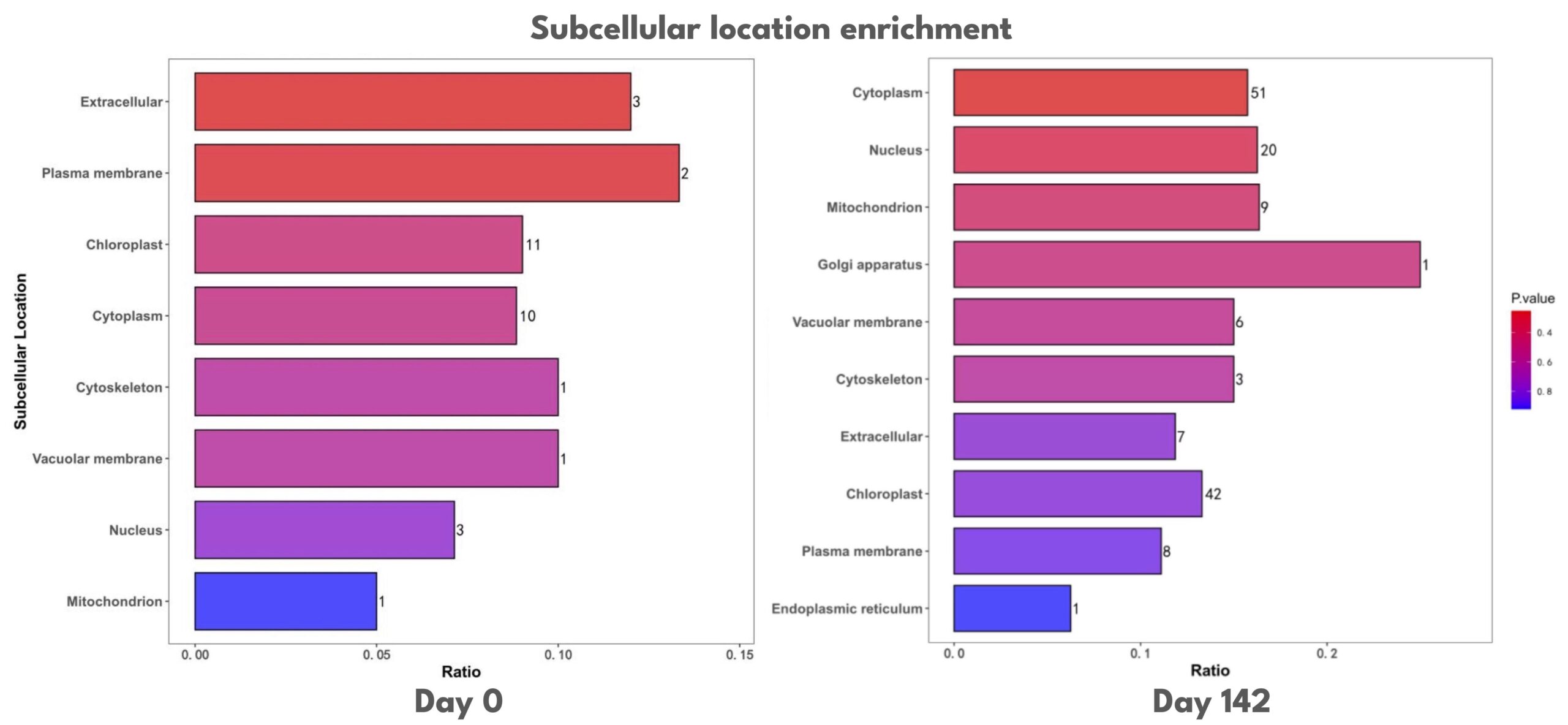

In olives (Olea europaea), we performed a controlled microbial amendment experiment across twelve trees split into control (n=6) and treated (n=6) groups, balancing cultivars (three Ascolana and three Mission per condition). The treatment group was drenched in a rich, diverse, concentrated beneficial microbial consortium and the control was drenched in plain water. The trees were allowed to grow from June to October of 2025. Root cuttings were collected once in June immediately before drenching and again in October. Cuttings were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and pooled within conditions and timepoints so each LC–MS sample represents a cultivar-mixed composite. At baseline, treated and control profiles were similar, supporting comparability prior to treatment. Over time, the treated condition diverged modestly from control with enrichment patterns consistent with potential coordinated remodeling of the root’s protein economy and trafficking infrastructure (cytoplasm, nucleus, ER, Golgi, membranes/endomembrane system, ribosome, extracellular region), alongside metabolic pathway engagement (e.g., central carbon routing and redox-linked processes) (Figure 4). If accepted at face value, this pattern may be consistent with time-dependent physiological integration of roots following microbial amendment, but care should be taken to interpret results within slight tissue-cutting and freezing variations (initial samples were frozen in microcentrifuge tubes while followup samples were frozen in 50-mL conicals).

Figure 4. Subcellular location enrichment of differentially expressed proteins at Day 0 and Day 142. Enrichment ratios represent the relative over-representation of subcellular compartments among differentially expressed proteins compared to the background proteome. Bar color indicates enrichment P-value, and numbers denote protein counts. Day 0 shows enrichment across membrane, cytoplasmic, and chloroplast-associated proteins, while Day 142 is characterized by enrichment of cytoplasmic, nuclear, and chloroplast proteins.

Figure 4. Subcellular location enrichment of differentially expressed proteins at Day 0 and Day 142. Enrichment ratios represent the relative over-representation of subcellular compartments among differentially expressed proteins compared to the background proteome. Bar color indicates enrichment P-value, and numbers denote protein counts. Day 0 shows enrichment across membrane, cytoplasmic, and chloroplast-associated proteins, while Day 142 is characterized by enrichment of cytoplasmic, nuclear, and chloroplast proteins.

Together, the fig and olive datasets point to the same thesis from opposite directions: microbial environments may track with measurable differences in rhizosphere metagenomic signal, and deliberate microbial amendment may drive coherent, time-dependent molecular restructuring in root physiology.

At the end of this reporting period, we can draw several practical conclusions while still noting where additional replication and analysis are needed. First, building self-sustaining predator infrastructure requires deliberately solving prey logistics: our aphid insectary system supplies prey to lacewings and is operationally compatible with a working greenhouse. Second, controlled enclosure experiments can transform “interesting observations” into interpretable results under farm conditions: using paired mesh chambers with matched trees allowed us to evaluate Rhyzobius lophanthae against scale on soursop and we observed strong suppression in the treatment chamber relative to the control chamber over 34 days. Third, commercially available microbial products should be treated as biological inputs that require verification rather than assumed label accuracy; routine microscopy checks are now part of our workflow. Finally, we generated molecular datasets (fig rhizosphere long-read metagenomics and olive root proteomics after microbial amendment) connecting cultivation practice and microbial intervention to below-ground biology. Next steps would include deeper metagenomic analysis (genomic binning, annotation, function-focused comparisons) and continued refinement/replication of enclosure-based biocontrol trials, with the goal of validating signals and turning these methods into practical, standardized greenhouse ecosystem design methodologies.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Education and outreach were a meaningful part of this project and reached both the local community and farm customers. We hosted a public on-farm event where visitors toured the greenhouses and learned about our biocontrol approach and plant health interventions. As part of the event, we presented a practical case study showing how a beneficial bacterial spray/consortium treatment was used to suppress and resolve powdery mildew on susceptible plants (including basil and jade), and we discussed how this connects to the broader goal of designing self-sustaining beneficial ecosystems. Attendance was strong, and visitors engaged directly with the science through Q&A and demonstrations. We also conducted outreach at the Roslindale farmers market, where we set up a hands-on educational “science station” alongside regular farm sales. We brought a contained terrarium demonstration featuring live lacewings and aphids to illustrate predator–prey relationships and explain how banker systems support beneficial insects over time. This format was especially effective for families and children, who could safely observe insects up close while learning about ecological relationships, pest pressure, and biological alternatives to chemical sprays. Together, these activities increased community awareness of biological control and gave the public a tangible window into how farm-based experimentation can support practical, environmentally friendly cultivation. Lastly, we presented our research to the GrowBoston network of urban farmers, a group assembled by the City of Boston's urban agriculture department. There were many interested farmers in our research on beneficial insects.

Learning Outcomes

Through this project we learned (i) that sustaining predatory insect populations in greenhouse systems is as much a prey-infrastructure problem as it is a predator-release problem, and that a rotating banker plant approach can make prey availability reliable and farmer-friendly; (ii) that free-release biocontrol observations in large, vented greenhouses are difficult to interpret without controls, and that small enclosure trials can provide a practical pathway to replicated, interpretable results without interrupting farm operations; and (iii) that commercial microbial amendments should be treated as variable biological inputs requiring verification, prompting the adoption of routine microscopy-based quality checks to strengthen experimental controls. We also gained hands-on experience generating and organizing large molecular datasets (long-read metagenomics and root proteomics) to connect field observations to measurable belowground biological signals. In addition, this grant functioned as a strong training platform for early-career researchers. Northeastern co-op interns and farm staff working on the project (including Mikayla, Elson, Ana, and Annalin) learned core experimental skills: forming hypotheses, designing controlled experiments, setting up appropriate controls, keeping clear records, and extracting interpretable conclusions from messy biological systems. They received practical training in microscopy and observational ecology—learning to patiently watch interactions (predator search behavior, prey selection/avoidance, and feeding) and translate qualitative observation into testable experimental questions. We also ran a journal club where interns read and presented peer-reviewed papers relevant to our work, which strengthened our collective understanding of biological control across microbial and insect systems (e.g., Trichoderma spp., Beauveria bassiana, entomopathogenic fungi, lacewings, parasitoid wasps, and related biocontrol strategies). Overall, a major educational outcome of this project was building local capacity for rigorous, farm-embedded science by training interns to think and work like experimentalists in real greenhouse conditions.

Project Outcomes

The beneficial insects generated genuine interest in our research from our young interns. The were excited to learn more about them, observe them and research them. They drew them, dissected them, observed them and were fascinated with how they helped our plants thrive. They got so excited by them that they figured out how to breed them. The project generated a lot of applicants to our farm and helped with employee retention and job satisfaction. Everyone wanted to work on the research. But the ultimate benefit by all was that we had a environmentally friendly and sustainable way to eradicate pests rather than utilize pesticides. Lastly, our plants were ultimately healthier.

When we proposed the project, we stated the following goals:

"""

Our project is designed to

achieve several objectives:

- Experiment with Three Major Ecosystem Designs: Test three unique ecosystems to identify the most beneficial synergies for plant growth, disease, and pest control. These will be tested sequentially to benefit from insights gained after each experiment. For each iteration, we will compare an untreated control against an experimental ecosystem, sending each for root exudate analysis. Along with root exudate analysis, we will also study insect populations to assess the designed ecosystems’ abilities to promote their recycling.

- Experiment with Many Minor Ecosystem Designs: This objective is the same as the previous, except these experiments will not be analyzed for root exudates, thus saving significant costs, allowing for rapid iteration.

- Standardize Ecosystem Design Methodologies: Standardize methods for designing and deploying self-sustaining ecosystems that maintain their health and productivity, even in the absence of immediate pest threats.

Through this project, we anticipate not only advancing our scientific understanding of soil microbiology and plant-microbe interactions but also

delivering practical, tangible benefits to farming practices. Our goal is to pave the way for more sustainable, efficient, and productive agriculture, rooted in a deep understanding of the soil's living tapestry.

"""

Looking back, this project set out highly ambitious goals, and in attempting to fulfill them uncovered idiosyncrasies of not only biological aspects of ecological engineering, but logistical properties as well. We came to terms with the large scale ordering and delivery of biological goods, the viability of microbial and entomological products on their arrival, the deployment of these products into our greenhouses and how they disperse and establish, and how those established populations begin to recycle according to deployment strategies and payload sizes. While not "more important" than the biological aspects of ecological engineering, they proved themselves to be foundational -- as the biological aspects (predatory-prey interactions, pathogen suppression, plant physiological responses) can't be studied otherwise -- and took up much of the human-attention-time of this grant. Nonetheless, the work produced clear operational lessons and several optimistic experimental outcomes.

Experiment with Many Minor Ecosystem Designs:

Minor ecosystem designs took up the entirety of Phase I of our project. This was a strategic choice decided on when scientific work on the farm began based on the notion that we should first establish a baseline for what plants respond to what interventions. We found this surprisingly recalcitrant, which much of our microgreens experiments yielding nearly no reproducible differences between conditions at all. Even when sterilizing soil, water, and seed surfaces, there were too many environmental variables (residual spores in the air, temperature and humidity variances, quality of microbial products, etc) to yield a clean signal. These early experiments guided us though toward experimental models that did respond (largely root-related experiments) and biological axes that were much more amenable to farmers and coarse scientific study alike (entomological interventions being the core of this). These insights paved the way for our Phase II where we conducted our major ecosystem design experiments.

Experiment with Three Major Ecosystem Designs:

In Phase II, we took what we learned from our minor ecosystem design experiments and this newfound intuition to design three capstone experiments. Namely, a root exudate study assessing the effects of microbial treatments on the olive root proteome, a Nanopore sequencing study assessing the effects of open-earth raised-bed cultivation compared to closed-pot cultivation for figs, and a biological control study assessing the effects of the beneficial beetle Rhyzobius lophanthae on the soft scale pest tentatively identified as Coccus longulus.

Economic and logistical constraints altered how we had originally imagined these three major ecosystem designs would unfold. However, we believe this increased -- not detracted from -- the scientific value of the work. The adjustments forced us to prioritize experiments that could survive real greenhouse conditions (labor limits, seasonal timing, biological product availability) while still producing interpretable outcomes. The resulting capstone experiments therefore represent designs that are not only biologically meaningful, but also operationally realistic for growers.

Standardize Ecosystem Design Methodologies:

Finally, standardizing ecosystem design methodologies remains a longer-term objective. While we certainly made progress, "standardizing ecosystem design methodologies" will be an ambition that we reserve to be something we are continuing to work toward rather than something we have accomplished as a result of this grant. We can provide the following heuristics though:

- If farmers are choosing between potted cultivation or raised-bed cultivation, raised-bed cultivation seems to provide plants with much richer access to microbial diversity than pots. If pots are the only option -- farmers may benefit from amending their potted soil with microbial products like Great White and Mikro-Myco to help compensate for the microbial diversity that would naturally colonize their soil in raised-bed cultivation.

- Farmers may benefit from building their own on-site insectaries if they are interested in using entomological biological control. In our vented greenhouse context, the quantities of insects we purchased and released were often insufficient for sustained suppression without a supplementary banker plant prey base. Establishing an on-site prey-production system (banker plants/aphid insectary) was the most cost-effective way we found to support persistence. This is largely a bioproduction challenge and something we foresee improving in the future, but for now, home-insectaries are the most economically realistic solution.

Note: The original proposal used the shorthand phrase “EPA approved” when describing the organisms and products used in this project. In practice, all organisms and microbial products employed were commercially available and widely used in agriculture under existing regulatory frameworks, though regulatory status varies by organism, formulation, and intended use. Certain applications explored in this work — including the use of Rhyzobius lophanthae against a scale insect tentatively identified as Coccus longulus — represent novel or non-standard use cases that have not been explicitly evaluated or approved by the EPA on a predator–prey–pairing basis. Regulatory status should therefore be considered context-dependent across specific organisms and use cases. All work was conducted responsibly using commercially available biological inputs or organisms harvested from the local native ecology.

This grant was made possible by a proud collaboration between

We Grow Microgreens, LLC and Earthbarrier Atmospheric Sciences Corporation