Progress report for FNE24-081

Project Information

Ley rotations have been shown to provide a diversity of ecosystem service benefits, including regulatory(such as climate and flood regulation), cultural (such as food security, farming communities, and recreation), and supportive (such as soil health, nutrient cycling, and biodiversity). However, the degree and types of services may vary depending on the management of the ley rotation system. Additionally, some aspects, such as the impact of livestock grazing or the impacts of the ley system on the soil microbiome, require further study.

Our objective is to clarify the soil and forage impacts of a no-input ley system with a 5- to 6-year pasture phase, incorporating rotational livestock grazing, and a 2- to 3-year mixed cereal and vegetable rotation. This type of pasture-dominant ley system with diverse cereal and vegetable

rotations holds potential for increasing the full suite of ecosystem service benefits for small to midsize meat and dairy farmers in the Northeast.

By incorporating laboratory tests of soil health, soil microbiology, and forage quality at all phases of the ley rotation, this study will investigate and

document that this system produces not only the soil health benefits observed by other peer studies on various ley systems, but also forage benefits (or at least neutral forage impacts) for the adopting livestock farmer. Additionally this study will begin to fill the gaps in our understanding of diverse, grazed, multi-species leys integrated with both cereal and vegetable production, particularly the impacts on soil microbial communities.

Our objective is to clarify the soil and forage impacts of a no-input ley system with a 5- to 6-year pasture phase, incorporating livestock grazing, and a 2- to 3-year mixed grain and vegetable rotation. Specifically, we will determine if this type of system will impact soil carbon sequestration. We will also look for other soil health effects, particularly changes in aggregate stability, bulk density, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other macro-minerals. Additionally, we will study the impacts on the soil microbiome. Does the physical disturbance of the ley or the selection of crop species have an

impact on the taxon diversity and functional biodiversity of the soil microbiome?

We further will test if these ley rotations can improve the nutrition of the resulting pasture-phase forage. We will test potential effects on energy

content and crude protein, as well as various macro- and micro-minerals.

Our hope is that this type of system can be expanded to small livestock and dairy farmers in the Northeast, to provide benefits to the farmer in both economic diversification and soil and forage quality outcomes. But first, we must better quantify the effects this type of ley has on the ecology and productivity of our regional system.

Modern agriculture, particularly in the United States, has seen an overwhelming shift toward intensification and specialization, i.e., monocultural, annual-heavy, continuous cropping systems that rely heavily on costly and environmentally detrimental fertilizers, pesticides, and tillage. These systems prioritize short-term yields in food and fiber productivity at the expense of longer-term benefits in regulating services (such as climate and flood regulation), cultural services (such as food security, farming communities, and recreation), and supporting services (such as soil health, nutrient cycling, and biodiversity).[1] Despite the critical ecosystem services provided by healthy soils; including stable carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, water storage and purification, and climate regulation, the intensified agricultural practices noted above continue to accelerate the rate of degradation of soil organic carbon (SOC), with agricultural food production contributing as much as 24% of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.[2] Within this context, there has been increasing interest and research into regenerative agricultural practices, often incorporating a return to older, more diversified systems, as a key solution to these challenges.

One such example of regenerative practices that has seen increased interest is the reintroduction of leys, or fully integrated crop-livestock systems (ICLS), also known as mixed farming systems, for climate resiliency, sustainability, and increased economic viability.[3,4] Research on these practices to date has shown promise in addressing the deficiencies in regulating, cultural, and supporting ecological services, but additional research is needed.[5]

Despite some excellent data from long-term ley experiments in northern Europe,[6-8] much work remains to be done to fully understand the myriad ecological and production impacts of different ley strategies. Cooledge et al.[5] noted the greater need to: 1) test all phases of the ley rotation; 2) better study microbial community composition, biomass, and diversity in multispecies leys under field conditions; 3) study the influence of grazed leys incorporated into arable rotations on soil structure and key measures of biological soil quality; and 4) study crop yields after livestock-grazed leys are returned to arable rotations. Much of the current literature on ley rotations either focuses on: shorter-term leys in predominantly arable cropping systems; systems without grazing impact; grazing systems where the rotations all contribute to livestock forage or feed, rather than vegetable and cereal food production; and/or systems that still amend soil with synthetic fertilizers, manure, or compost.

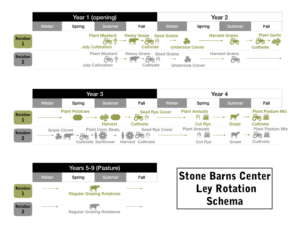

Over the last fifteen years, SBC has conducted informal experiments to develop and refine a 7- to 8-year, pasture-dominant, livestock-grazed, no-input, rain-fed, multi-species ley rotation system. Ley plots within this system rotate between a 5- to 6-year mixed grass and forb ley phase incorporating at least 10 species of seeded grasses, forbs, and legumes, and a 2- to 3-year grain and vegetable phase that incorporates cover crops and additional grazing (see “Materials and Methods'' for details). This system has great potential for incorporation by small to mid-size, Northeast meat and dairy farmers, either through single-farm diversification or partnerships with nearby crops operations, to provide greater economic resiliency, improved production outcomes, and improved ecological services. However, before we expand to a large study with partner farms (and other interested parties) and thoroughly explore the economic challenges and impacts of adopting this system, we must conduct formal research to better quantify the basic production and ecological services implications of this particular type of ley system at our existing scale.

By incorporating tests of soil structure and health, soil microbiology, and forage quality at all phases of the ley rotation, this study will investigate and document that this ley system produces not only the soil health benefits observed by other peer studies on various ley systems, but also forage benefits (or at least neutral forage impacts) for the adopting livestock farmer. Additionally this study will begin to fill the gaps in our understanding of diverse, grazed, multi-species leys integrated with both cereal and vegetable production, particularly the impacts on soil microbial communities. If this study is successful, we will seek future funding and use this data to recruit partner farms for a larger scale, multi-farm study that will incorporate detailed economic and greenhouse gas life cycle analyses.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

Research

Ley Management and Treatment Groups

While we will not manipulate the basic management of the leys as part of this experiment, the no-input rain-fed ley system we have developed over 15 years of experimentation plays a crucial role in this study by providing the successful model to test. Additionally, because the rotation is on-going, it will provide leys, cereal blocks, and vegetable blocks at all stages of the system so that we can determine the effects of different aspects of the rotation during the short two-year study period.

While there is some variation in grain and vegetable species and variety selection and the timing of grazing events, each ley plot within our system follows the same basic management cycle. Leys are opened from pasture in July, cultivated and seeded to mustards. The mustards receive a hard graze from one of our livestock groups in September, then the plots are cultivated and seeded to winter grains. Clover is then frost-seeded under the grains in late February/early March the next year. Grains are harvested in July, leaving the clover understory, which may or may not be grazed. Here leys may diverge based on location:

- Some leys are cultivated in October and planted half in garlic, followed by buckwheat, with the other half planted in potatoes in April. These leys are then seeded to winter rye in October after the harvests. The rye is cut in May and the plot is seeded to summer annuals for grazing. The plot is then cultivated and seeded back to pasture (Albert Lea Super Grazing Mix; ten planted species including two legumes) in September.

- Other leys, after grain harvest, are cultivated in May and seeded to corn, beans, and sunflowers. Then the fields are seeded to winter cover crop grains in October. Grains are cut in May and the plot is seeded to summer annuals for grazing. Finally those plots are cultivated and seeded back to pasture (Albert Lea Super Grazing Mix) in September.

Specific variations in each ley will be carefully documented and reported, but for the purposes of this study, it is important that each ley will go through a primary grain phase and a primary vegetable phase. No ley that doesn’t meet these minimum requirements will be included in the study.

Treatment Groups

Due to the inability to follow an individual ley through a full cycle in a two-year study, we will be using the variety of leys in different stages of the rotation across our landscape to study the impacts of each phase of the ley rotation. Thus our different treatment groups in the study will be: Fully Mature Pre-Ley Pasture (n = 5), Post-grain Rotation (n = 5), Post-vegetable Rotation (n = 3), 1st Year Post-Ley Pasture (n = 1), 2nd Year Pasture (n = 3), 3rd Year Pasture (n = 4), 4th Year Pasture (n = 3), and 5th Year Pasture (n = 2). Additionally, we will be able to compare this data to control data collected using identical procedures from our perennial cool season pasture plots without leys (n = 13).

Soil Sampling

Soil Health Analysis

Soil health sampling will generally be conducted in August, with the exception of soil samples taken at the end of the pasture phase in June before the ley is opened. We will collect soil samples using the spade method. Fifteen randomly distributed subsamples will be taken from within each ley, thoroughly mixed, and then a composite soil sample of approximately 2000 cm3 will be taken from the mix to be sent for analysis. Soil samples will be refrigerated until ready for overnight shipment.

We will send soil samples for testing at Woods End Laboratories LLC (Augusta, ME). Samples will receive the following key analyses: Total-C, LOI Organic Matter,C:N ratio, Aggregate Stability, Bulk Density, Nitrate, Extractable-P, K, Ca, Mg, Na, pH, Al, Swiss-P, Cu, Mn, Zn, B, and Mo.

Soil Microbiome Analysis

We will use 250mg of the fresh soil from the composite soil health sample, on the day of collection, to extract nucleic acids for microbiome barcoding analysis. DNA/RNA extraction will be performed in our on-site laboratory using the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit reagents and protocol. The bead beating step of the extraction will be performed with a BeadBug™ 3 Position Bead Microtube homogenizer. After extraction, samples will be stored in a -80C freezer until they are ready to be shipped for analysis.

PCR amplification and full-length amplicon sequencing (Pac Bio Sequel II) of the extracted DNA will be performed by Integrated Microbiome Resource (Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, CA). We will be using the 16S, 18S, and ITS primers for ribosomal RNA. The 16s gene/primer is a common primer for soil bacteria barcoding, while ITS is a useful gene/primer for fungal barcoding, and 18s will give us additional fungal taxa, as well as other Eukarya such as soil nematodes.

The testing by Integrated Microbiome Resource will also include a basic bioinformatic analysis package. This will provide: Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) analysis, phylogenetic trees, taxon level assignments, measures of alpha and beta microbial diversity, and an analysis of functional diversity using the PICRUSt2.0 algorithm for each sample. Additionally, we will look closely at the fungal to bacterial ratios for each sample.

Forage Sampling and Analysis

Forage sampling will generally be conducted in May during peak growth of cool season grasses. The one exception will be first year pasture post-ley, which will be sampled in September to give ample time for germination and growth.

Vegetation will be clipped with pruning shears from 15 randomly selected locations within each ley. Approximately 250 cm3 of material will be collected at each location from a variety of vegetation levels including canopy and understory. The composite sample should fill a gallon zip-lock bag. Samples will be immediately transferred to a -23C freezer post-sampling for storage until shipping for analysis.

Testing will be done by the Dairy One Forage Laboratory (Ithaca, NY) using their “Basic Plus Minerals” wet chemistry analysis. This analysis will include: dry matter, TDN, crude protein, fiber, Ca, P, Mg, K, Na, Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn, Mo.

Statistical Analysis

In addition to summary statistics for all treatment groups and tests, we will use Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to look for clustering and separation of the various treatment groups in multivariate space in relation to suites of variables (soil health parameters or forage quality parameters). For example, we suspect that when a ley rotation is seeded back to pasture, there is a successional effect as the pasture grasses re-establish themselves, so a pasture may take a few years to mature. If this is true, we might see a clustering of pastures past a certain age compared to younger pastures based on multiple forage quality variables, and this might help us better understand patterns in the data. It is also likely that we will use MANOVAs to test for significant differences between the ley pastures and control perennial pastures in their soil health, soil microbiology, and forage quality characteristics. We will use post hoc tests to further explore any significant results.

Changes from our original methods included adding forage biomass sampling in the second year of the project to compare forage production in addition to forage nutrition in the ley rotation pastures versus the perennial cool-season pastures. Additionally, we changed our statistical analysis plan as the complexity of the data collected emerged and we had to deal with issues like repeated measures from the same plots in multiple years or at multiple sampling sites. For most major statistical significance testing we ended up switching to multivariate mixed effects models, except for specialized testing of the significance of distance measures for data like beta diversity when analyzing the microbiome data.

It is important to note that in this study, we were comparing the ley rotations not to conventional systems, but to other high quality regenerative management techniques. Our diverse cool-season pastures are managed using holistic, multi-species, rotational grazing techniques with a minimum of 45-60 days of rest between grazing events. Our native warm season pastures were recently established without the use of herbicides by combining tillage for vegetation termination and cover cropping for weed management with repeated grazing events. Once established, the native pastures contained a diverse mix of four native warm season grasses and thirteen different climate- and grazing-tolerant native forb and legume wildflowers. Our cropping systems incorporate seven (vegetable) and ten (greenhouse) year crop rotations, extensive cover cropping, an organic amendment (primarily based on compost incorporating animal inputs), and an IPM/Organic style intervention strategy for pest and weed challenges. This may explain why even the cropping systems were indistinguishable from the other management treatments for many measures (including soil total carbon percentage). Even so, the pasture-dominant ley rotations performed exceptionally well compared to the other systems. In particular, the improvements in forage nutrition and forage biomass would be of great interest to Northeast grass-fed livestock operations. The soil health and soil microbiome characteristics of the ley rotations which were comparable to perennial grassland systems may have significant impacts on the quality of the grains and vegetables grown during the cropping phase of the rotation and we have some preliminary anecdotal information to that effect regarding the cereal grains grown as part of the ley rotations. This is an area we hope to explore further in the future.

This study sought to better understand and objectively quantify the potential ecosystem and agricultural production services of a pasture-dominant ley rotation system incorporating diverse animal impact. We studied the soil health, forage nutrition, forage production, and soil microbiome impacts of this ley system compared to other regenerative agriculture management systems such as rotationally-grazed perennial cool-season pasture, rotational cropping systems incorporating cover cropping and animal-input-based compost, as well as early establishment native warm season grassland restorations. We exceeded the objectives of our study with the addition of forage biomass measurements and deeper soil microbiome analyses and data than expected.

We hope to use this data to promote these pasture-dominant ley rotations as a diversification and forage production strategy for Northeast livestock farming operations (individually or in cooperation with neighboring cropping operations). This study has provided a wealth of compelling data to help promote adoption of these strategies.

Internally, the soil microbiome data has exceeded our expectations and will lead both to farm improvements in management and strategy, but also new research directions regarding the impact of soil microbiome on taste and nutrition.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

We held a half-day field day and tour for Blue Hill at Stone Barns’ front-of-house apprenticeship program participants around the ley rotation project. Participants learned about the ley rotation system and the research project, then participated in soil sampling and observed the laboratory DNA extraction.

Additionally, we toured the Director of Research at the Greenacres Foundation and Farm through one of our ley pastures in late 2024 and described the program in the hopes of spurring future collaborative efforts around the project between the two organizations. We have conducted several other tours of the ley rotation project for visiting farmers and agricultural researchers.

Finally we have presented two seperate educational programs (2024 and 2025) on the ley rotation project to our restaurant partner chef team and Stone Barns Center members, followed by a field tour of one of the ley pastures. Our program in 2025 was particularly well attended with 30+ members attending the inside portion of the program and probably 75% of participants continuing on the field walk, despite a cold winter day.

Learning Outcomes

-Forage nutrition and production outcomes

-Soil health (including building soil organic matter) outcomes

-Increased understanding of how to properly run a ley system and its benefits

-Increased understanding of the impact of management treatments on soil microbiomes and how to incorporate soil microbiome data into management decisions

Project Outcomes

We completed our second year of research successfully, including collecting a full round of soil samples for soil microbiome analysis, successfully extracting and purifying soil DNA and sending the DNA to Integrated Microbiome Resource for amplification, sequencing, and initial bioinformatic analysis. All samples were successfully amplified and sequenced. We also added a forage biomass protocol in 2025 which turned out to be informative. We are currently in the process of wrapping up final statistical analyses and producing two draft manuscripts for publication. One manuscript will cover the soil health, forage nutrition, and forage biomass parts of the project and the second manuscript will focus exclusively on the soil microbiome.

Soil Health

Management Type Soil Health Analysis

The multivariate mixed model revealed distinct treatment and temporal responses among soil variables (REML = 2615.3). Random effects indicated substantial plot-to-plot variability, particularly for potassium (K) and phosphorus (P), with strong correlations among nutrient pools (e.g., r_N,TC ≈ 0.99).

Baseline means (reference treatment and year) differed markedly by response variable, reflecting the differing measurement scales of each nutrient pool.

Treatment responses were outcome-specific (Table 1):

- K increased significantly under our cropping rotations (field and greenhouse) compared to the ley rotations (+117 ± 38, p = 0.004).

- P also increased strongly under our cropping rotations compared to leys (+241 ± 34, p < 0.001).

- N increased in our native warm season establishment plots compared to ley rotations (+63 ± 18, p < 0.001).

- Aggregate Stability (AS) and Total Carbon % (TC) showed no significant treatment effects.

Between years, K decreased (-51.6 ± 8.2, p < 0.001) while N increased (+37.0 ± 7.8, p < 0.001), with no significant change for AS, P, or TC.

Plot-level random intercepts explained large portions of total variance, and random-effect correlations suggested that plots with high N also tended to have high TC (r ≈ 0.99) but low AS (r ≈ -0.68).

Within Ley Rotation Soil Health Analysis

The multivariate mixed model explained variation among outcomes well (REML = 634.3) with substantial plot-level variance for K and P. Sub-treatment P1 (first-year pasture) produced significant reductions in potassium (–236 ± 66, p = 0.0027) and phosphorus (–176 ± 79, p = 0.042) relative to P6 (final year of the pasture phase) which was set as the baseline ley treatment. Potassium also tended to be lower under the grain rotation (G) sub-treatment (–81 ± 39, p = 0.051). Suggesting that the grain and vegetable phases had a definitive affect on lowering P and K levels, which were at least partially recovered in the later years of the pasture phase. No other sub-treatments affected nitrogen, volumetric aggregate stability, or total carbon compared to sixth-year pasture. Nitrogen showed a marginal increase between years (+25 ± 14, p = 0.073). No significant year effects were detected for other outcomes.

Table 1. Fixed effects from the multivariate mixed-effects model (lmer: value ~ 0 + y_var + y_var:(treatment + year) + (0 + y_var | plot_id)).

Estimates represent outcome-specific deviations (± SE) from the ley management treatment and year. Significance levels: *p < 0.001, p < 0.01, p < 0.05, †p < 0.10. Treatment C = Cropping, Treatment N = Native Warm Season Establishment, and Treatment P = Perennial Cool-Season Pasture.

| Outcome | Effect | Estimate (± SE) | t value | p value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | Treatment C | 3.4 ± 11.1 | 0.31 | 0.76 | No effect |

| Treatment N | 0.6 ± 18.1 | 0.03 | 0.97 | No effect | |

| Treatment P | 5.4 ± 8.7 | 0.62 | 0.54 | No effect | |

| Year | –7.6 ± 7.8 | –0.98 | 0.33 | No change | |

| K | Treatment C | +117 ± 38 | 3.09 | 0.004 | ↑ under C |

| Treatment N | –13 ± 48 | –0.28 | 0.78 | No effect | |

| Treatment P | +27 ± 21 | 1.26 | 0.21 | No effect | |

| Year | –51.6 ± 8.2 | –6.27 | <0.001 | ↓ over time | |

| N | Treatment C | +10 ± 11 | 0.94 | 0.35 | No effect |

| Treatment N | +63 ± 18 | 3.51 | <0.001 | ↑ under N | |

| Treatment P | –15 ± 9 | –1.75 | †0.082 | Marginal ↓ | |

| Year | +37 ± 7.8 | 4.75 | <0.001 | ↑ over time | |

| P | Treatment C | +241 ± 34 | 7.03 | <0.001 | ↑ under C |

| Treatment N | –72 ± 43 | –1.65 | 0.11 | No effect | |

| Treatment P | –32 ± 20 | –1.57 | 0.12 | No effect | |

| Year | +6.9 ± 8.2 | 0.84 | 0.40 | No change | |

| TC | Treatment C | +1.3 ± 11.0 | 0.12 | 0.90 | No effect |

| Treatment N | 0.08 ± 18.0 | 0.00 | 1.00 | No effect | |

| Treatment P | –0.2 ± 8.7 | –0.02 | 0.98 | No effect | |

| Year | +0.6 ± 7.8 | 0.08 | 0.94 | No change |

Forage Nutrition and Biomass

Forage Nutrition

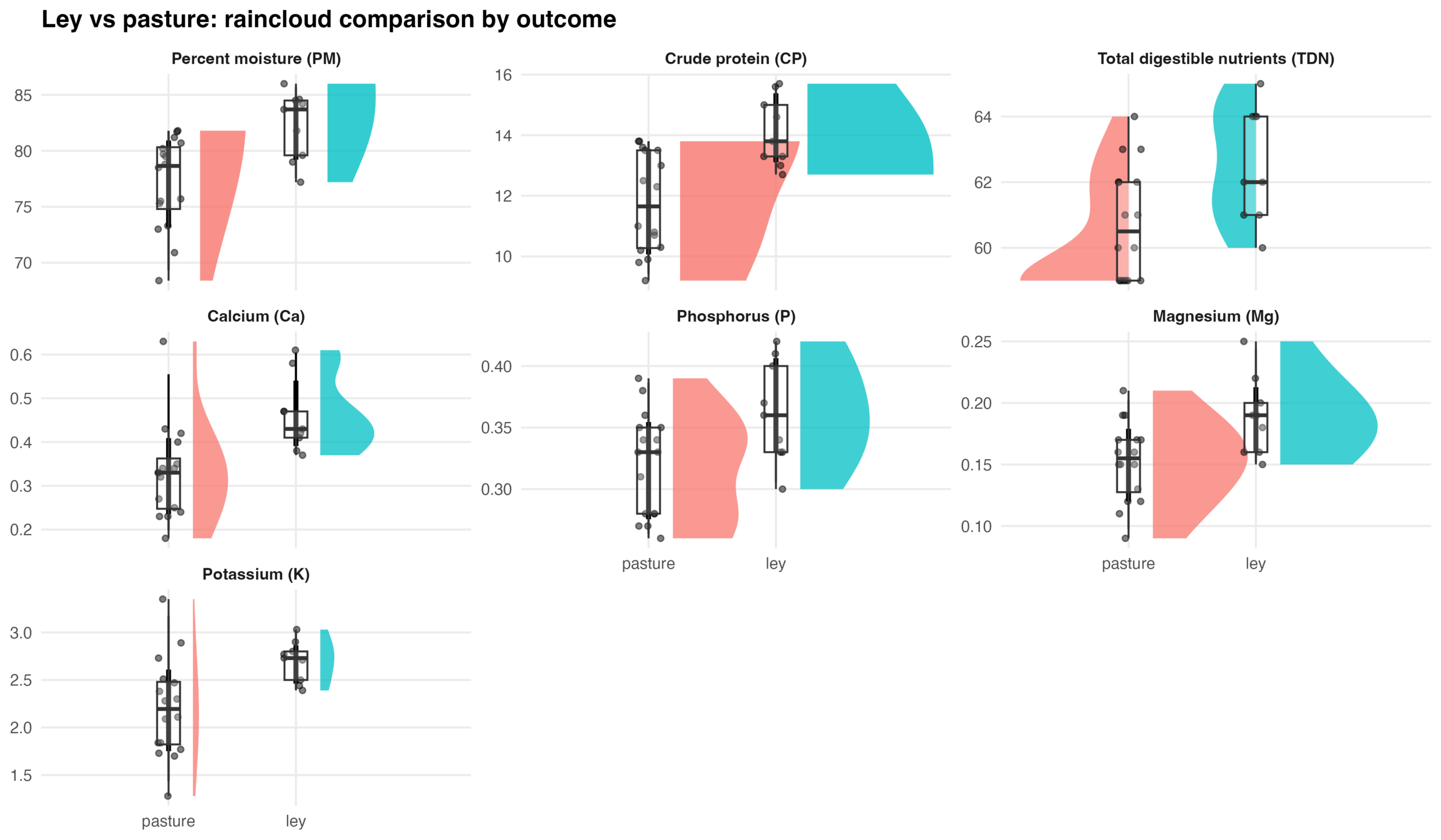

The multivariate mixed model explained variation among outcomes well (REML = 511.4). Random effects indicated substantial plot-to-plot variability for crude protein (CP), percent moisture (PM), and total digestible nutrients (TDN), while mineral nutrients (Ca, Mg, P) showed very little variability among plots. The simplified random structure (using independent random intercepts per outcome) achieved convergence and produced stable fixed-effect estimates. Compared with leys, perennial pasture exhibited lower crude protein (−2.32 ± 0.71, p = 0.006), lower percent moisture (−5.01 ± 1.96, p = 0.024), and lower total digestible nutrients (−1.70 ± 0.66, p = 0.023). Over time, forage digestibility (TDN) increased significantly (+1.54 ± 0.39, p < 0.001), while percent moisture tended to decline slightly (−0.80 ± 0.42, p = 0.061). Mineral concentrations (Ca, K, Mg, P) showed no significant treatment or temporal effects.

Forage characteristics differed significantly between leys and perennial pastures. Leys produced forage with higher percent moisture, higher crude protein, and higher digestible energy compared to perennial pasture. These differences indicate that leys support improved forage quality and nutritional value. Over the study period, forage digestibility (TDN) increased, while percent moisture declined slightly, potentially reflecting rainfall trends between years. Mineral nutrient concentrations (Ca, K, Mg, P) remained stable across treatments and years, suggesting consistent mineral composition. Overall, ley rotations enhanced both the nutritional quality and energy value of forage compared with perennial pasture, without altering the mineral nutrient balance. We recommend future research into the relative contributions of sward maturity, sward composition, and/or soil characteristics (including the soil microbiome) to the observed forage nutrition differences between ley rotation pastures and cool-season pastures managed only through rotational grazing.

Figure 1. Raincloud plots comparing forage composition in ley and perennial cool-season pasture systems. For each outcome, half-violin density plots show the distribution of observations by management system (pasture vs. ley), overlaid with individual plot-level observations (points) and boxplots indicating the median and interquartile range. Outcomes include percent moisture (PM), crude protein (CP), total digestible nutrients (TDN), calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), and potassium (K). Facets are scaled independently to reflect differences in measurement units and ranges among variables.

Forage Biomass

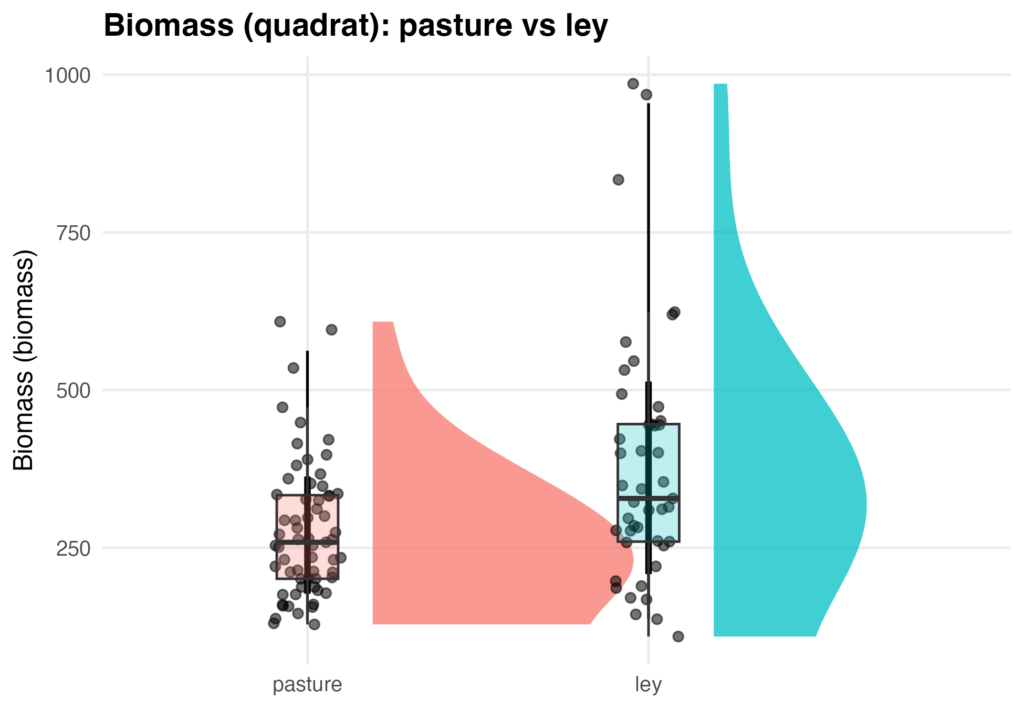

The mixed-effects model converged successfully (REML = 1371.5). Plot-level variance was 1,872 (SD = 43.3 g/m²), and residual variance among quadrats within plots was 21,407 (SD = 146.3 g/m²). Approximately 8% of total variance occurred among plots and 92% within plots, indicating high small-scale heterogeneity typical of diverse pastures. Mean biomass in ley plots was 380.3 ± 29.2 g/m², while perennial pasture plots averaged 276.8 ± 38.2 g/m². The difference (−103.5 ± 38.2 g/m²) was statistically significant (t(10) = −2.71, p = 0.022). Converted to field-scale units, leys produced approximately 3,395 lbs/acre and pastures 2,469 lbs/acre of forage, indicating that leys yielded about 27% more biomass than perennial pastures, assuming vegetation is equally palatable for livestock in both treatments.

Figure 2. Raincloud plot comparing quadrat biomass in pasture and ley systems.

Raincloud plots show the distribution of quadrat-scale forage biomass samples for pasture and ley treatments. Half-violins represent kernel density estimates of biomass values, points show individual quadrat observations, and boxplots indicate medians and interquartile ranges. Ley plots exhibited higher central tendency and greater upper-range biomass relative to pasture plots. Consistent with these patterns, mixed-effects modeling of quadrat biomass—accounting for plot-level structure and repeated sampling—indicated significantly greater biomass in ley systems compared with pasture, supporting the conclusion that ley management increases forage biomass at the quadrat scale.

Soil Microbiome Analysis

Alpha Diversity Measures

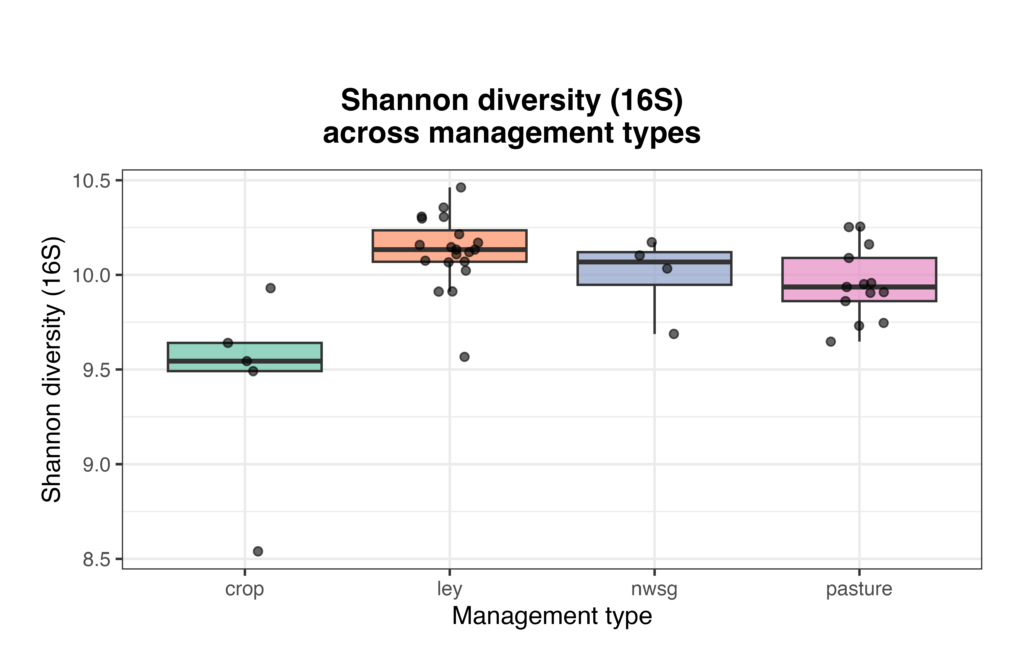

Bacterial Diversity (16S)

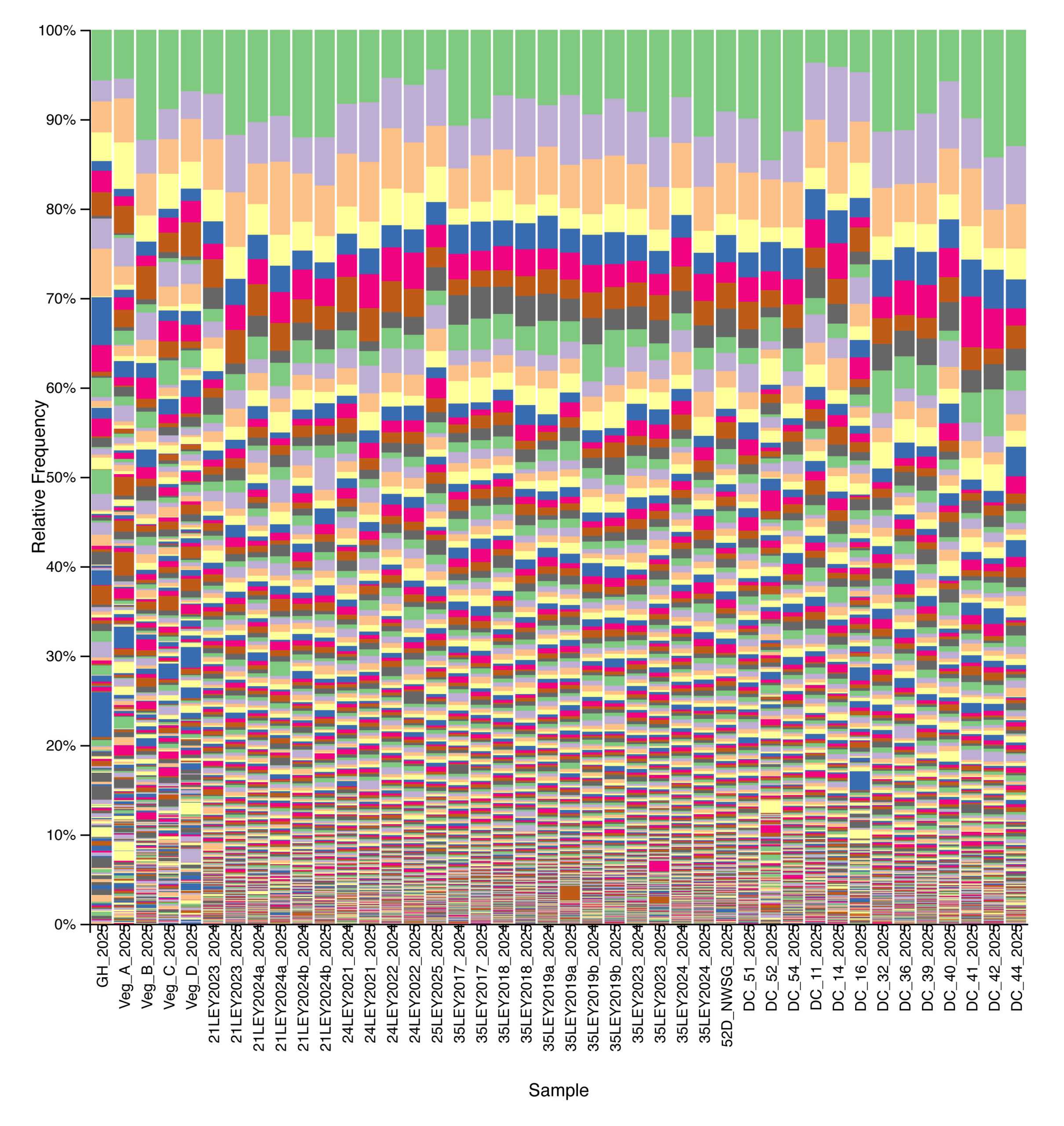

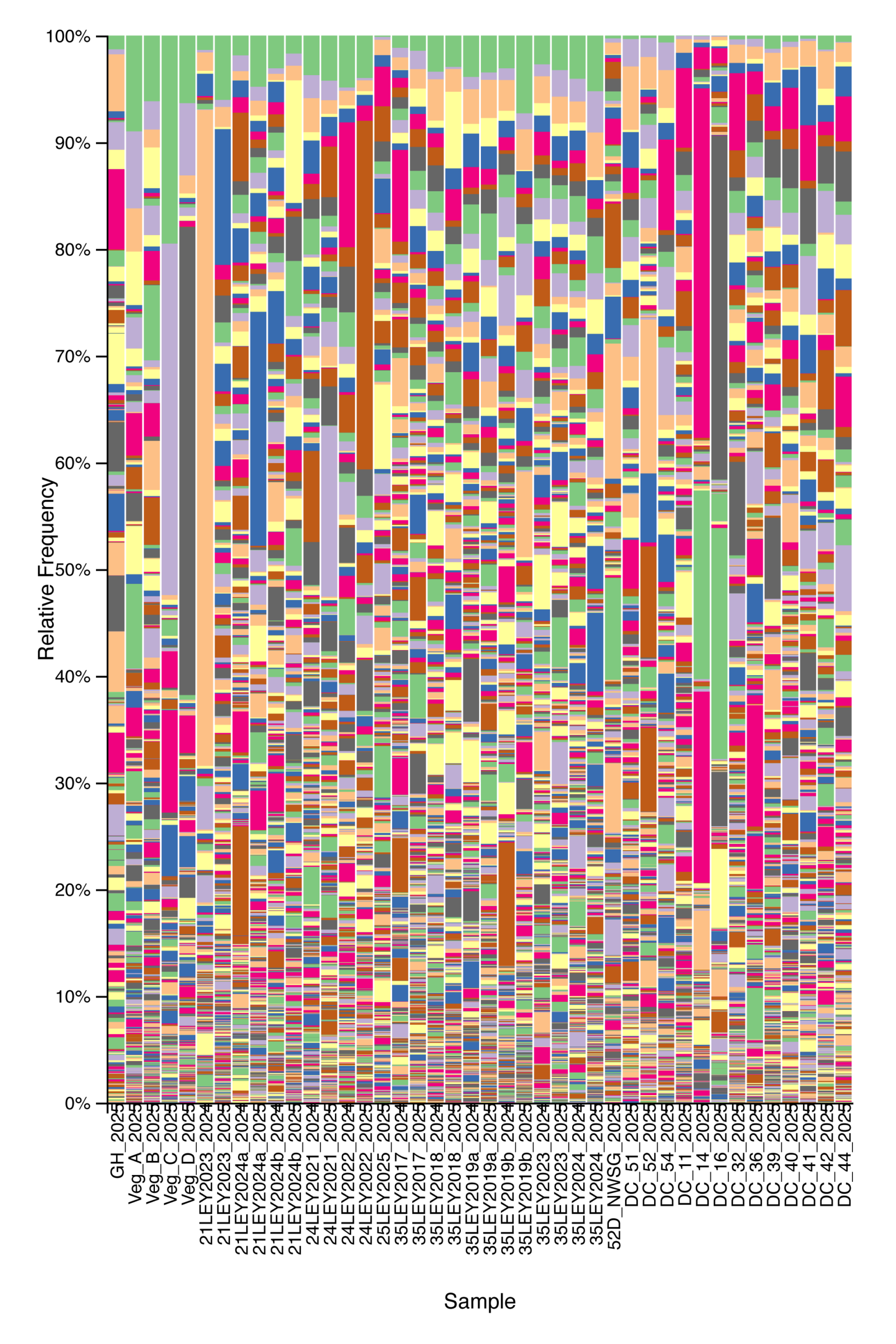

Bacterial community composition and alpha diversity varied across management types based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Relative abundance profiles showed broadly similar dominant taxa across all samples, with substantial within-group variability, but samples cluster visually by management system when ordered from crop fields through ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment, and cool-season pastures (Fig. 3). Shannon diversity differed among management types, with crop fields generally exhibiting lower bacterial diversity, while ley rotations and native warm-season grass systems showed higher and more consistent diversity values (Fig. 4). Cool-season pastures displayed intermediate diversity with greater variability among samples. Together, these results indicate that management system is associated with shifts in both bacterial community structure and overall diversity.

Figure 3. Relative abundance of bacterial taxa across agricultural and grassland systems based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Each stacked bar represents a single soil sample, ordered from left to right by management type: crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment, and cool-season pastures. Colors denote distinct bacterial taxa.

Figure 4. Bacterial alpha diversity (Shannon index) from 16S rRNA gene sequencing across agricultural and grassland management types. Each point represents a soil sample, with boxplots summarizing the distribution within crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment (NWSG), and cool-season pastures.

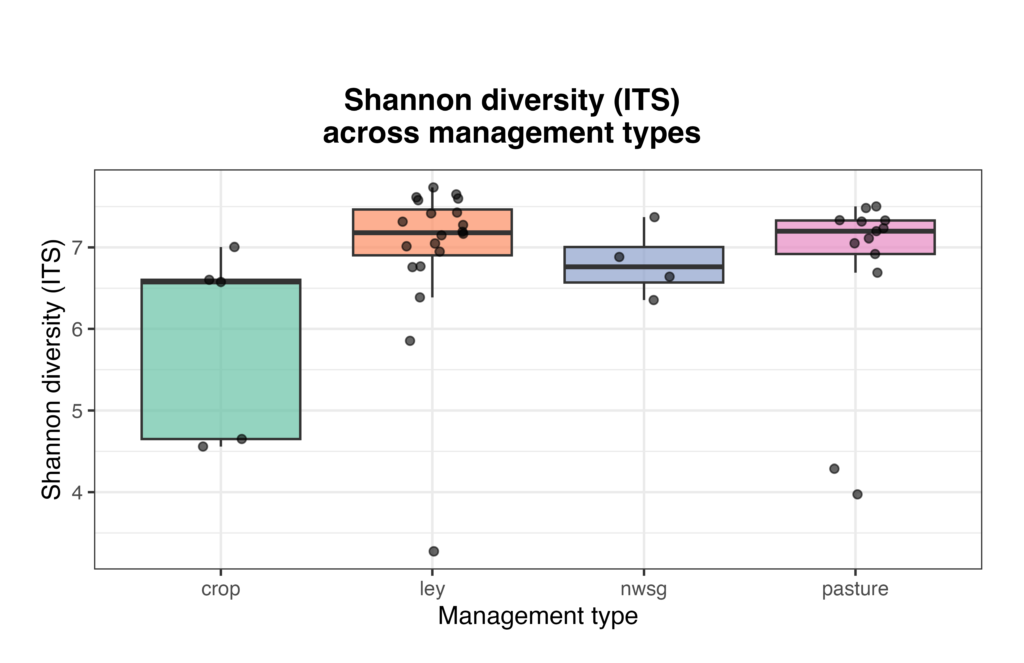

Fungal Diversity (ITS)

Fungal community composition and alpha diversity varied among management types based on ITS sequencing. Relative abundance profiles indicated substantial heterogeneity in fungal community structure across individual samples, with broadly similar dominant taxa present across crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment, and cool-season pastures, but with marked variation in relative abundances among samples (Fig. 5). Shannon diversity of fungal communities differed across management types, with crop fields generally exhibiting lower and more variable diversity, while ley rotations and cool-season pastures showed higher median diversity values (Fig. 6). Native warm-season grass systems displayed intermediate fungal diversity with relatively consistent values among samples. Overall, these patterns suggest that land management is associated with differences in fungal community structure and diversity.

Figure 5. Relative abundance of fungal taxa across agricultural and grassland systems based on ITS sequencing. Each stacked bar represents a single soil sample, ordered from left to right by management type: crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment, and cool-season pastures. Each color band indicates distinct fungal taxa.

Figure 6. Shannon diversity (ITS) of soil fungal communities across management types. Each point represents an individual soil sample, with boxplots summarizing distributions within crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment (NWSG), and cool-season pastures.

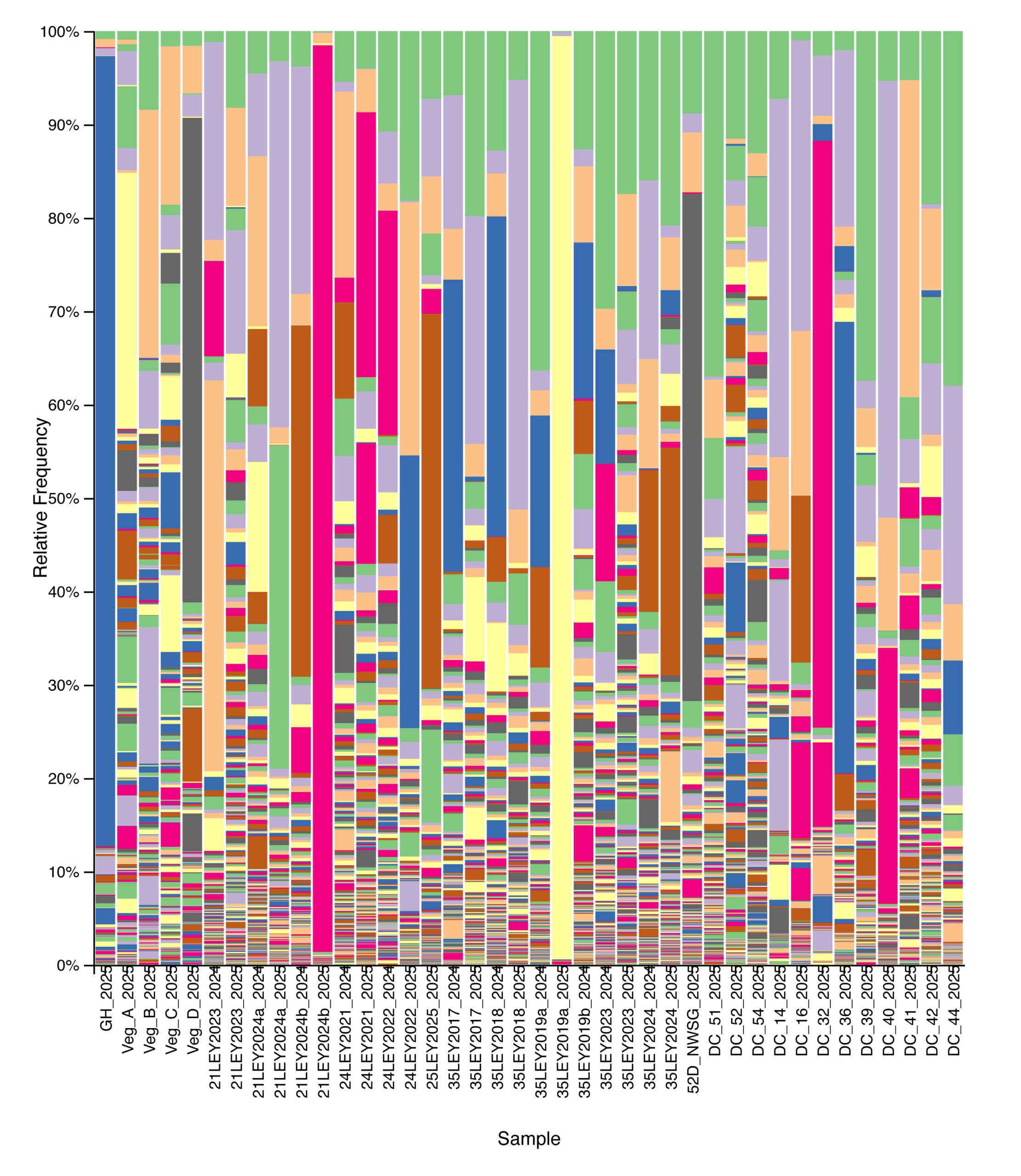

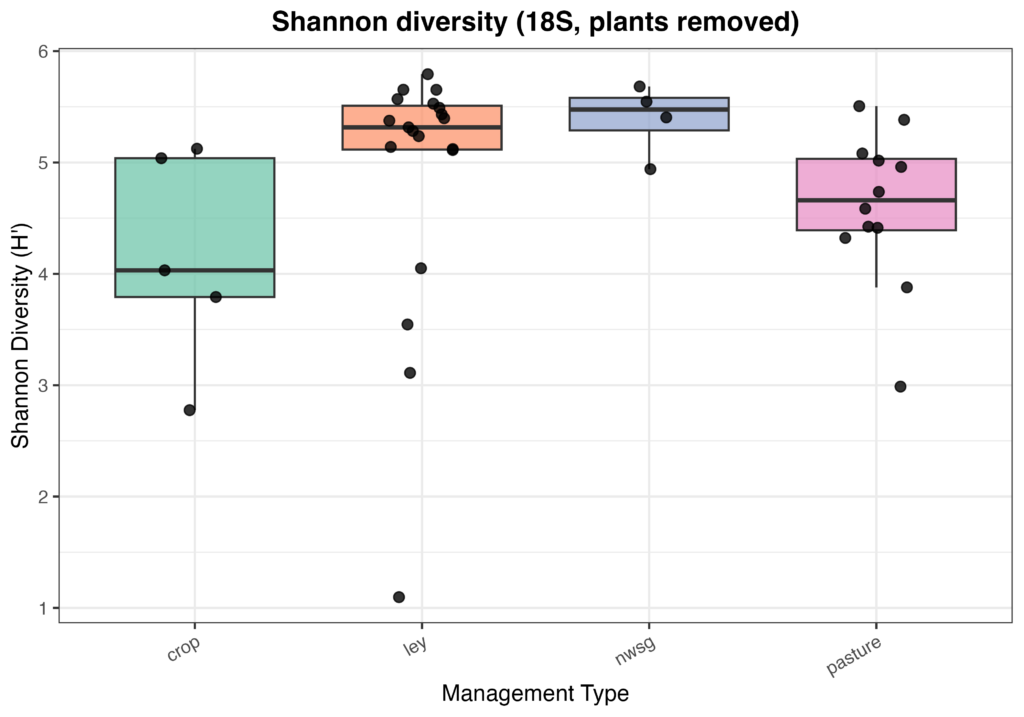

Microeukaryotic Diversity (18S)

Eukaryotic community composition and alpha diversity varied among management types based on 18S rRNA gene sequencing. Relative abundance profiles indicated substantial variability in eukaryotic community structure across individual samples, with plant-derived sequences contributing prominently to overall community composition when retained (Fig. 7). Following removal of plant signal, Shannon diversity differed among management types, with crop fields generally exhibiting lower and more variable eukaryotic diversity, while ley rotations and native warm-season grass systems showed higher median diversity values (Fig. 8). Cool-season pastures displayed intermediate diversity with greater variability among samples. Overall, these patterns suggest that land management is associated with differences in soil eukaryotic community structure and diversity.

Figure 7. Relative abundance of eukaryotic taxa across agricultural and grassland systems based on 18S rRNA gene sequencing. Each stacked bar represents a single soil sample, ordered from left to right by management type: crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment, and cool-season pastures. Colors indicate distinct taxa. Plant-derived sequences were retained in this analysis.

Figure 8. Eukaryotic alpha diversity (Shannon index) from 18S sequencing across management types following removal of plant-derived sequences. Each point represents an individual soil sample, with boxplots summarizing distributions within crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment (NWSG), and cool-season pastures.

Beta Diversity Measures

Management effects on community composition were strongest for bacteria, intermediate for fungi, and weakest for protist and other microeukaryotic communities.

Bacterial Beta Diversity (16S)

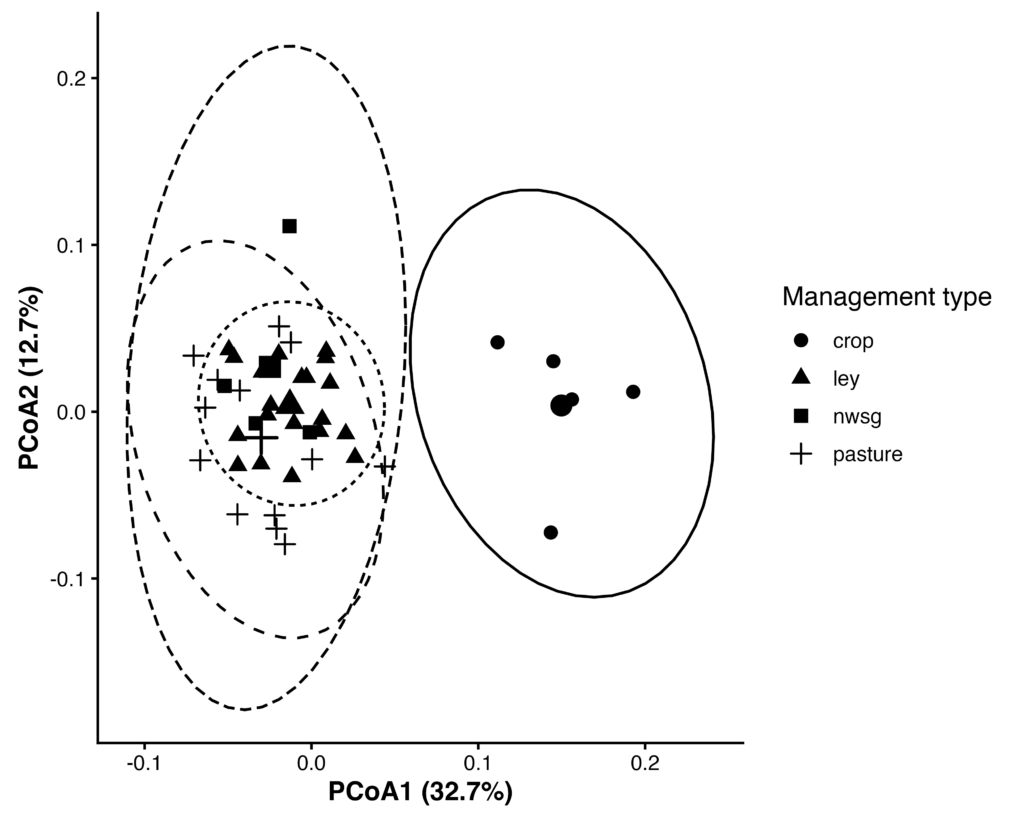

Bacterial community composition differed significantly among management types based on Weighted UniFrac distances (PERMANOVA, F₍3,38₎ = 5.94, R² = 0.32, p = 0.001; 999 permutations). Multivariate dispersion did not differ significantly among management types (PERMDISP, F₍3,38₎ = 1.63, p = 0.195), indicating that observed differences reflect shifts in community composition rather than heterogeneity of within-group variance.

Pairwise PERMANOVA analyses (Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted) indicated that bacterial communities in cropland soils differed significantly from ley, pasture, and early-establishment native warm-season grass systems (padj ≤ 0.01), whereas communities among ley, pasture, and native grass systems did not differ significantly.

Figure 9. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of bacterial communities based on Weighted UniFrac distances. Points represent individual samples, grouped by management type; larger symbols indicate group centroids, and ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals. Community composition differed significantly among management types (PERMANOVA, R² = 0.32, p = 0.001), with no significant differences in multivariate dispersion (PERMDISP, p = 0.195).

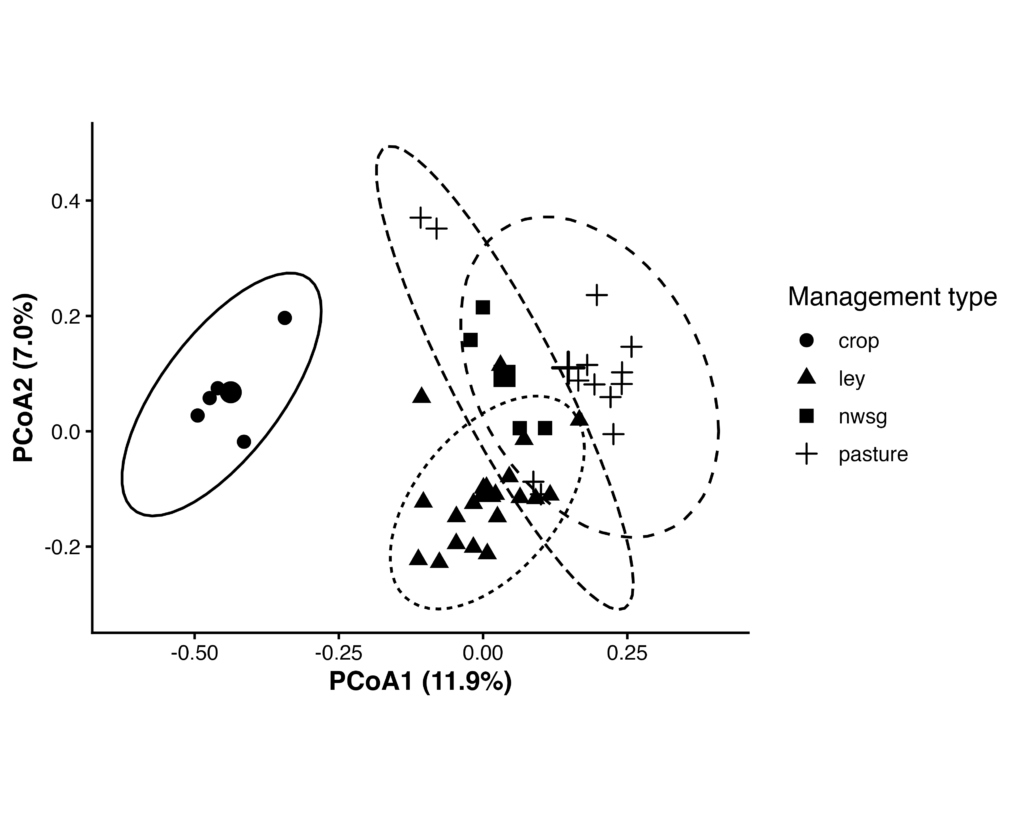

Fungal Beta Diversity (ITS)

Fungal (ITS) community composition differed significantly among management types based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities (PERMANOVA, F₍3,38₎ = 2.97, R² = 0.19, p = 0.001; 999 permutations). Multivariate dispersion did not differ among management types (PERMDISP, F₍3,38₎ = 0.30, p = 0.833), indicating that PERMANOVA results were not driven by differences in within-group variability.

Pairwise PERMANOVA analyses (Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted) indicated significant differences in fungal community composition among all management types, although effect sizes were smaller than those observed for bacterial communities.

Figure 10. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of fungal communities based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities. Points represent individual samples grouped by management type; larger symbols indicate group centroids, and ellipses denote 95% confidence intervals. Community composition differed significantly among management types (PERMANOVA, R² = 0.19, p = 0.001), with no evidence of differences in multivariate dispersion (PERMDISP, p = 0.833).

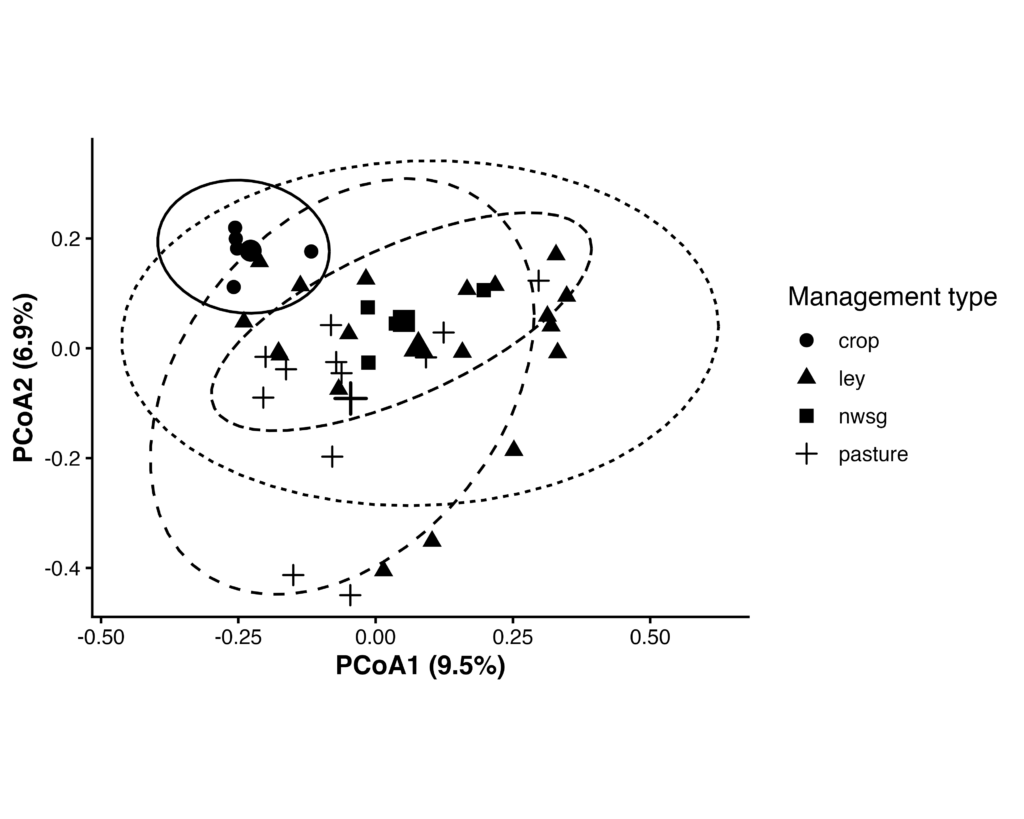

Microeukaryotic Beta Diversity (18S)

Protist and other microeukaryotic community composition (18S rRNA gene) differed significantly among management types based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities (PERMANOVA, F₍3,36₎ = 1.83, R² = 0.13, p = 0.001; 999 permutations). Multivariate dispersion did not differ significantly among management types (PERMDISP, F₍3,36₎ = 1.77, p = 0.157), indicating that differences in community composition were not driven by unequal within-group variability.

Pairwise PERMANOVA analyses (Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted) indicated that cropland communities differed significantly from perennial systems, whereas differences among perennial management types were weaker and in some cases not statistically significant.

Figure 11. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of 18S rRNA gene communities based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities. Points represent individual samples grouped by management type; larger symbols indicate group centroids, and ellipses denote 95% confidence intervals. Community composition differed significantly among management types (PERMANOVA, R² = 0.13, p = 0.001), with no significant differences in multivariate dispersion (PERMDISP, p = 0.157).

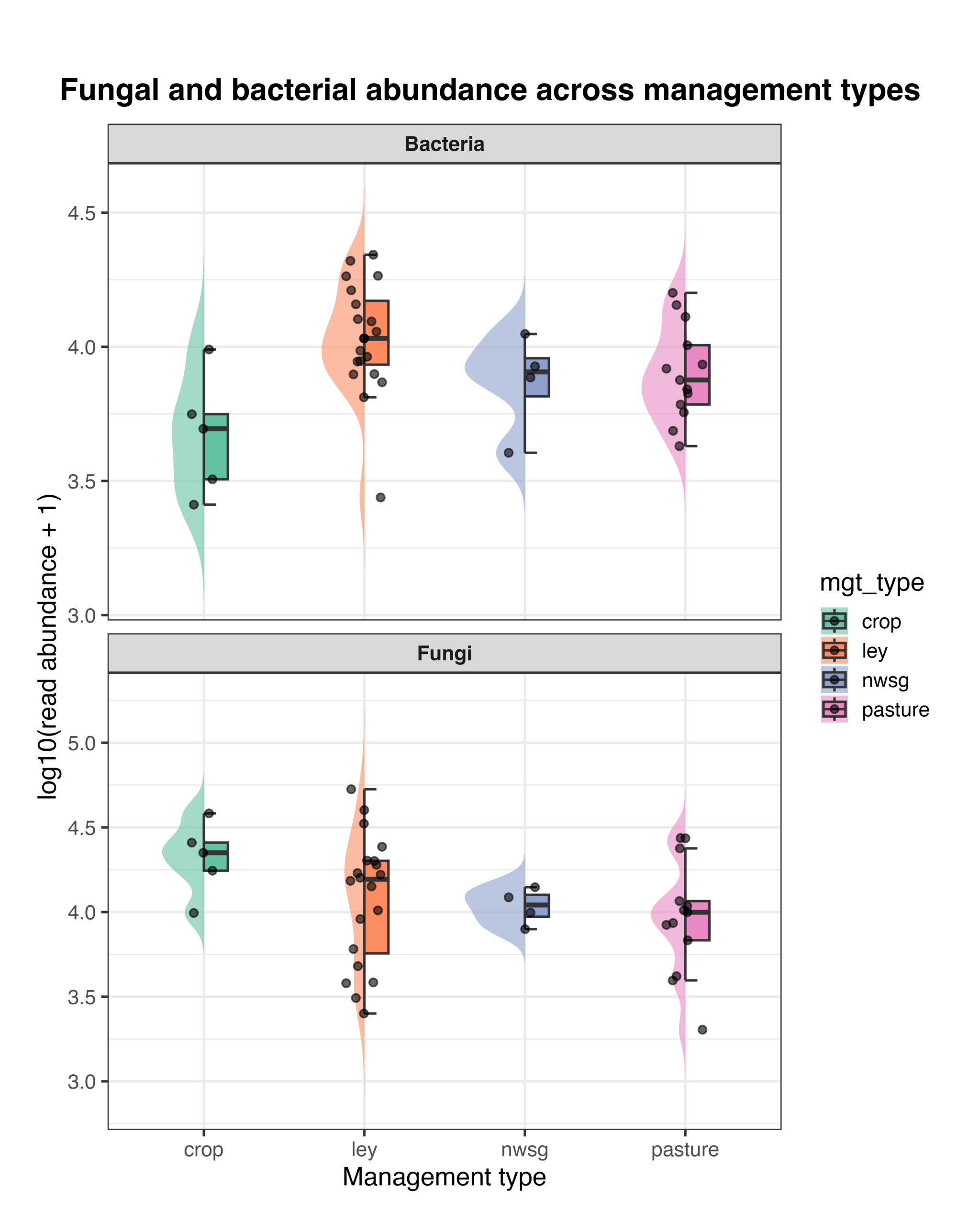

Fungal and Bacterial Abundance

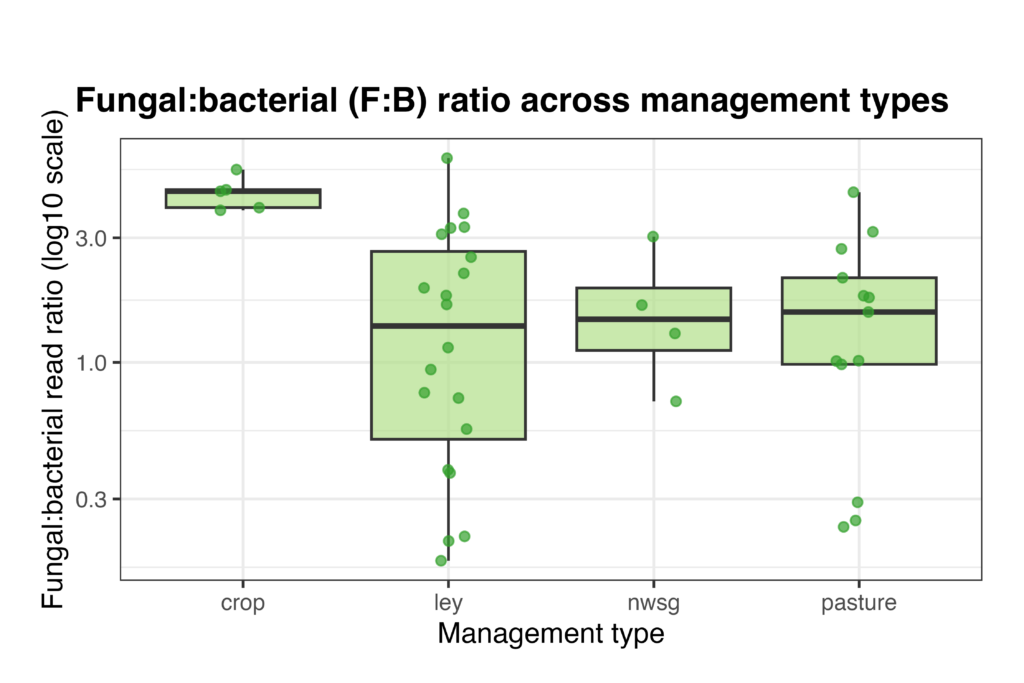

Bacterial and fungal read abundances, as well as the fungal:bacterial (F:B) ratio, varied among management types. Distributions of log-transformed read abundances showed differences in both bacterial and fungal sequencing depth across systems, with crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment, and cool-season pastures showing distinct patterns of central tendency and variability (Fig. 12). The F:B ratio also differed among management types, with crop fields generally exhibiting higher ratios and ley rotations showing greater variability among samples, while native warm-season grass and cool-season pasture systems displayed intermediate values (Fig. 13). Because these metrics are derived from amplicon read abundances rather than absolute biomass, they should be interpreted as relative indicators rather than direct measures of organismal abundance. However, the use of consistent primer sets and sequencing protocols across all samples allows for meaningful comparison of relative differences among management types, providing insight into how land management is associated with shifts in soil microbial community balance.

Figure 12. Raincloud plots showing bacterial (top panel) and fungal (bottom panel) read abundance across management types. Abundances are shown as log10-transformed read counts (+1). Violin plots represent the distribution of values, boxplots indicate the median and interquartile range, and points represent individual soil samples. Management types include crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment (NWSG), and cool-season pastures.

Figure 13. Fungal-to-bacterial (F:B) read ratio across management types. Ratios were calculated from ITS and 16S read abundances and are shown on a log10 scale. Points represent individual soil samples, and boxplots show the median, interquartile range, and 1.5× IQR for crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment (NWSG), and cool-season pastures.

Agriculturally Important Microbial Functional Guilds

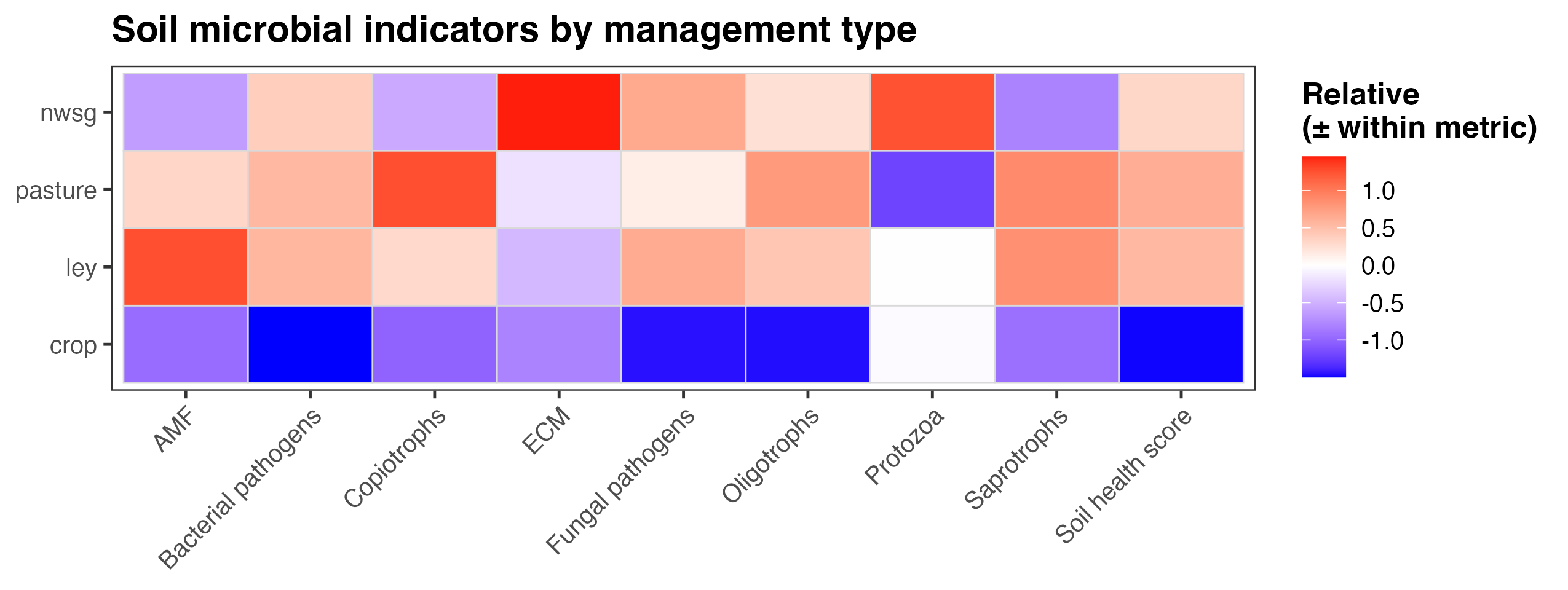

An integrated soil microbial health score revealed consistent differences among management types. Functional group indicators were derived from relative read abundances of microbial taxa associated with key ecological roles, including arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), ectomycorrhizal fungi (ECM), saprotrophs, bacterial copiotrophs and oligotrophs, protozoa, and potential bacterial and fungal pathogens. For each indicator, values were standardized within metric to allow comparison of relative patterns across management systems rather than absolute abundances. The overall soil health score represents a composite summary of these standardized indicators, integrating signals associated with nutrient cycling capacity, trophic complexity, and potential disease pressure. Across management types, crop fields generally exhibited lower relative scores across multiple functional groups and the overall soil health index, while ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment, and cool-season pastures showed higher and more balanced profiles (Fig. 14). These results suggest that diversified and perennial management systems are associated with microbial community structures indicative of enhanced soil ecological function.

Figure 14. Heatmap of soil microbial indicators, including an overall soil health score, summarized by management type. Values represent relative, standardized deviations within each metric (mean-centered and scaled), allowing comparison of patterns across management systems rather than absolute magnitudes. Colors indicate higher (red) or lower (blue) values relative to the overall mean for each indicator. Management types include crop fields, ley rotations, native warm-season grass establishment (NWSG), and cool-season pastures. Note that the color scheme for bacterial pathogens, fungal pathogens, and Copiotrophs is flipped compared to the other categories, as higher abundance of these three functional groups indicate lower soil health and increased disturbance ecologies. Note also that the pathogen categories indicate risk only, as in many cases the taxonomic assignments weren't able to distinguish between pathogenic species/strains and ones that might be neutral or even beneficial.

Statistical Analysis Of Soil Microbiome Characteristics

To assess the effects of management state on soil microbiome diversity and functional outcomes, we applied a multivariate mixed-effects modeling framework to a dataset comprising multiple microbiome and microbial soil health response variables. This approach enabled simultaneous inference across outcomes while accounting for repeated sampling of experimental plots and shared sources of variability.

Response variables included bacterial (16S rRNA gene), fungal (ITS), and broader eukaryotic (18S rRNA gene) alpha diversity (Shannon index), a phylogenetically weighted functional redundancy index derived from metagenome-assembled genome annotations, a fungal-to-bacterial read ratio, and a composite soil health index based on agriculturally relevant functional guilds. To place outcomes on a common scale and facilitate comparison of effect sizes across metrics, all response variables were standardized to z-scores prior to analysis.

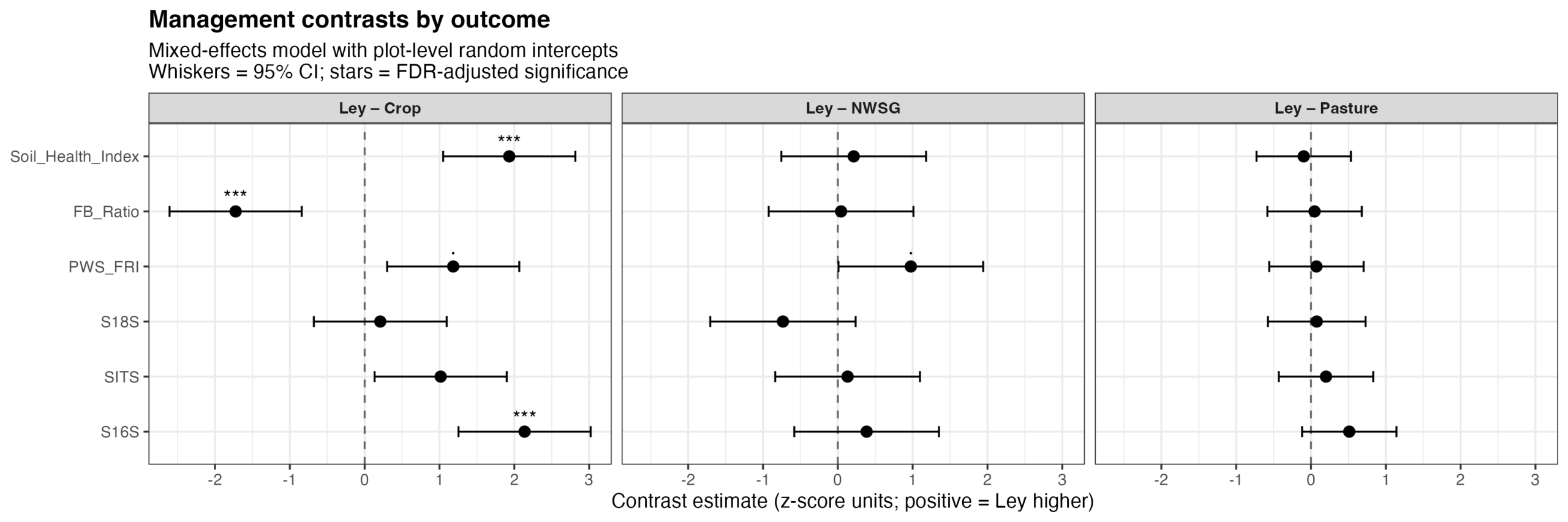

Management state significantly influenced microbiome and functional outcomes (p = 0.004), with strong outcome-specific responses (outcome × management interaction, p < 0.001). Cropped systems consistently differed from the more perennial management types (including ley rotations); exhibiting reduced bacterial alpha diversity, elevated fungal-to-bacterial ratios, and lower soil health index values (Fig. 15). Predicted functional redundancy also tended to be lower under cropping relative to ley, pasture, and native warm-season grass systems. In contrast, fungal and broader eukaryotic alpha diversity metrics were comparatively less responsive to management state.

Figure 15. Estimated contrasts between ley management and alternative management states (crop, pasture, and native warm-season grass; NWSG) across microbiome diversity and functional outcomes. Points represent estimated marginal mean differences (Ley − comparator) from a mixed-effects model with plot-level random intercepts, fitted to standardized (z-scored) response variables. Horizontal whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals. Positive values indicate higher values under ley management relative to the comparison treatment. Significance symbols denote false discovery rate (FDR)–adjusted p-values (p < 0.05; p < 0.01; **p < 0.001; · p < 0.1). Bacterial alpha diversity (16S Shannon), fungal:bacterial ratios, and a soil health index showed strong and consistent differences between ley and cropping systems, whereas differences between ley, pasture, and native warm-season grass systems were comparatively small. Phylogenetically weighted functional redundancy (PWS_FRI) exhibited a positive but marginally significant difference between ley and crop management.

One key challenge we encountered in our first year was working in a complex environment with many projects and events occurring simultaneously throughout the landscape, handled by multiple teams, which can cause communication mishaps. Specifically, several of our experimental plots were mowed before spring forage testing took place, reducing our overall forage testing sample size. We still were able to manage a reasonably sufficient sample size, but this spurred us to continue working on our methods of organizational communication around projects and experiments on the landscape and we had no similar incidents during the 2025 data collection season.

We were able to answer the questions we set out to study during the grant period; however, due to the short two year timeline for the grant period, we are applying for grants to extend and expand the study (one USDA-AFRI grant currently pending). We feel the current methodology and the conclusions we can draw from the study will be greatly strengthened by increased sample size, the ability to follow the same plot through all phases of the rotation (see Figure 1), and off-farm replication and study of this particular ley system. We also think the research can be strengthened and interpretation challenges addressed if we were able to add additional protocols, such as greenhouse gas flux monitoring and monitoring of the biomass production and/or harvest biomass for crops. For instance, if the leys are sequestering more carbon in the surface soil, what if the increased tillage and animal impact are spurring the emissions of greater amounts of greenhouse gasses such as nitrous oxide? Without monitoring greenhouse gas emissions, we can not fully understand the potential climate impacts of our ley rotation system and how it compares to the climate performance of our perennial grassland pastures. We also feel there is increased need to understand the potential crop nutrition impacts of this system, particularly in light of the microbiome findings, in addition to the forage nutrition impacts documented.

As we complete the final months of this study, we will look for ways to share the results and learnings from this project with farmers in the Northeast, particularly small dairy and meat livestock farmers. We are planning to submit two journal manuscripts on this work by February 2026 and potentially present a poster sesson or talk at a relevant conference.