Final report for FNE24-083

Project Information

To view this report with a Table of Contents for easier navigation, please use this PDF version: FNE24-083 Final Report with TOC.

Our project team designed this project to:

- Understand nutrition underlying 2023 animal enthusiasm about our SARE FNE22-013 field-edge tree/shrub leaf-silages, plus explore additional tree/shrub species including some deemed “invasive;”

- Explore why my animals limit their consumption of regionally abundant Red (and Sugar) Maple leaves, and contribute data to limited scientific understanding of toxicities present in maple species plus Staghorn Sumac; and

- Delineate safe use of wild Cherry species with regard to cyanide (HCN) levels - Black Cherry in particular grows substantially along field edges, and was a livestock top choice in FNE22-013.

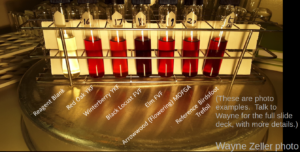

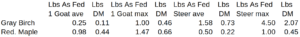

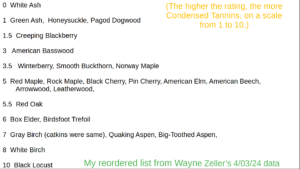

Dairy One Forage Laboratory (Ithaca, NY) completed nutritional analyses on 102 leaf-samples of 20 tree, 11 shrub and 1 vine species, including 25 matched fresh/ensiled sample-pairs to look at nutritional changes when ensiled. We ordered quantification of Soluble Protein (SP) and Rumen-Degradable Protein (RDP), with partial success (many of those tests failed), and Wayne Zeller, US Dairy Forage Research Center (Madison, WI), screened 30 species of our leaf-samples for relative Condensed Tannin (CT) levels, plus has 9 more species to do (this work is outside of the commitments in our proposal). SP, RDP and CT levels give clues about ruminant digestive utilization of protein, with CT increasing utilization from all feedstuffs by as much as 25%.

High energy and low fiber traits of tree leaves were confirmed: our leaf-silage averaged 120% of the Water Soluble Carbohydrate % of Dry Matter level (WSC, % DM) of Dairy One average grass-silage, with more than twice as much Non-Fiber Carbohdrates (NFC, % DM) overall (NFC includes WSC).

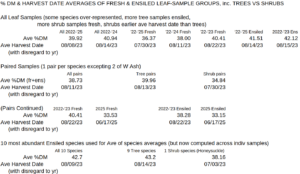

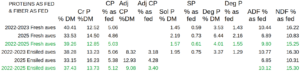

Harvest-date comparisons were confounded by differing quality of 3 sites harvested consecutively (see 2 “Harvest-date” spreadsheets under “Results”). Earlier-harvested 2025 samples did show the expected trend of higher protein and lower energy % of DM than later-harvested 2022-’24 samples, with less pronounced difference in levels as fed (versus DM).

We had Dairy One analyse 4 long-fermented (>1 yr) leaf-silage samples for 6 acids normal to grass and corn silages, as follow-up to 2019 short (<1 yr) Fermentation Profiles which found almost none (see “Fermentation” spreadsheet under “Results”). Those acids did appear.

We ordered analyses of fats (Fat Ether Extract = Fat EE) and Ash, in order to obtain accurate NFC figures; average leaf-silage Fat content was 147% of the average Dairy One grass silage figure, and averaged 111% of levels in matched fresh leaf-samples (see “All” and ”Paired” spreadsheets under “Results”). Cutin and wax leaf coatings are an unknown portion of this, and are said to be indigestible.

Our new website is launched, built of colorful downloadable PDFS, so that I Shana can update them myself, off-line on browse walks. I added annotations to items on the “Tree Fodder & Climate Resources” page, and the “Farm Research” page has a Table of Contents, to find a short exhibit for each study easily. Links to reports, data sheets, presentations and articles are included for each study. The old website remains up and functional as well, for now. We await feedback from users.

Since start of this project 22 months ago, I’ve given 17 presentations at 9 event venues, and tabled twice. Venues beyond Maine were NOFA MA “Go Nuts” on-line agroforestry discussion series, Vermont Farm to Plate on-line, a NY agricultural educators’ Agroforestry Group x 2 on-line, and the intermational Short Rotation Woody Crops Conference at University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry in person. A second Poor Proles Almanac podcast interview, this time about results of these SARE projects, has aired, (I dread to hear from listeners: I was late and stressed, so caused Andy to be short of time). Links to both segments of the first are posted on the websites below.

See the new https://3streamsfarm.wixsite.com/3streamsfarm , or the old https://3streamsfarmbelfastme.blogspot.com , for various presentation recordings and slide PDFs with full text.

To view this report with a Table of Contents for easier navigation, please use this PDF version: FNE24-083 Final Report with TOC (also available under Information Products).

This Project enabled us to seize an opportunity for analyses of SARE FNE22-013’s vast tree/shrub-leaf-silage sample-bank collected/frozen in 2023, plus obtain additional leaf-samples for diverse forage analyses at 6 laboratories, to bridge an informational gap that has been slowing livestock farmers from productive use of woody perennial forages, when weather challenges limit grass-forage harvests.

We:

-

Broadened analyses of nutrition, ensilement and digestibility to 32 tree/shrub/vine species including 7 deemed “invasive,” for generalizable findings on change from ensilement, plus per-species info sought by Northeastern farmers;

-

Broadened toxin testing to 3 cherry and 4 maple species plus Sumac, exploring Black Cherry harvest dates, wiltedness, and ensilement time-periods, to shed new light on farmer and livestock risk in using maple/cherry abundance along field edges;

-

Obtained analyses of one sample per leaf-silage barrel fed during our winter goat/steer intake/milking trial, more than meeting academic standards for triplicate samples per 9 species fed (and samples ordered by dates fed are available, to correlate with frozen milk samples for further study);

-

Re-created our website, and updated and used our listserve, to streamline dissemination of woody forage information.

Northeastern farmers now have guidance to effectively supplement ruminant rations with alternative on-farm forages.

Northeastern farmers’ climate risks around grass-based forage continue. In 2023, water-logged fields caused a first-harvest hay-scramble in mid-August. Nutritional quality of such late first-cut is poor, and second-cut was low in volume. Grass baleage provided to Meadowsweet Farm was also cut late; farmer Eliot VanPeski said the condition of his grass-fed cattle was diminished, due to poor baleage quality.

Cattle browse-lines are evident on field-edge trees of most Northeastern dairy farms. Tech Advisor Karl Hallen observed in his past herd that his highest-performing cattle were doing most of that browsing; Fred Provenza stated that ruminants perform better across the board with access to woody browse (5/21/20 webinar hosted by Didi Pershouse). Tree/shrub leaf-silage can extend both known and (humanly) unknown benefits into ruminant winter diets.

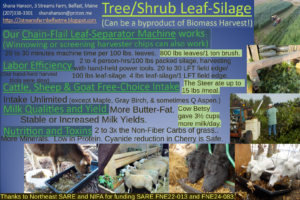

Our weather-resilient SARE FNE 22-013 harvest of field-edge trees and shrubs started as soon as Doak’s Machine finished upgrades on the Chain-Flail Leaf-Separator prototype in late June, and yielded slowly but plentifully. Cutting with hand-held power-tools, and stripping leaves with this machine prototype (created by current Tech Advisor Karl Hallen) which is 90% quicker than traditional hand-stripping, we produced 2,500+ gallons of tree/shrub leaf silage (70 of 60-70 planned barrels) in only 1,000 lineal feet of field edges (our proposal identified 5,700 LFT for potential harvest).

Cattle generlly eat 12% Dry Matter (DM) of woody browse, sheep 20% and goats 60% (Lindsay Whistance, 12/10/21 Silvopasture webinar hosted by Steve Gabriel, Wellspring Forest Farm); my steer Angelo in SARE FNE22-013, with unlimited access to that low-quality 2023 late-cut hay, consistently chose tree/shrub leaf-silage as 33% DM of his (grain-free, forage only) diet across three separate 11-day periods of one 2 hour offering-period/day. Angelo kicked up his heels to gallop to it (he only trotted quickly for the alternate-period offerings of 2nd-cut hay); I did not weigh him, but he outgrew draft tack and looked great all winter.

Positive livestock palatability responses from SARE FNE18-897 (Hanson 2020a) and VTGF Mini-Grant nutritional results (Hanson 2020b) preceded SARE FNE22-013 (Hanson 2025), which added data on HOW MUCH my steer and goats will eat, and on whether leaf-silage can support milk production (it does). The SARE 24-083 upon which we report overlapped that study, using fresh and ensiled leaf-samples taken during FNE22-013 harvests and winter livestock trials, plus additional new leaf-sampling, to explore nutritional levels (more thoroughly than in previous VTGF study), nutritional changes when ensiled, cherry-leaf cyanide (HCN) toxin levels when fresh, ensiled or dried, and little-known toxicities present in maple species.

This project enlisted my past SARE FNE18-897 intern Emily MacGibeny to support positive change in our web presence, where I can now make more efficient and organized updates, so that farmers can better access this new information plus other resources on use of tree/shrub forages.

I went beyond committed testing, laboriously packing leaves into bags and containers for additional nutritional tests with some on my own dime (I got curious), and packing numerous samples for Wayne Zeller, US Dairy Forage Research Center (Steve Gabriel attested to the time this takes, in his SARE FNE 19-930 report, Gabriel 2022)). Wayne is working on a monumental task in a context of diminished lab assistance, to isolate, purify and identify Condensed Tannins (CT) from 26 species with comparative CT levels above or equal to “5” (on a 1 to 10 scale, with Birdsfoot Trefoil reference at “6”), plus up to 9 more of our species if they screen to have similarly high levels. Perhaps farmers will no longer need bioengineered tannin-producing white clover and alfalfa, once our more traditional woody sources are understood.

Scott Radke, toxicologist at Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, continues to go beyond ordered Cyanide testing as I write this report, to find references which might shed light on our surprising data, and repeat tests with extreme results. Everyone that I became linked to through this study has shared a steep learning curve, while addressing the multi-faceted knowledge gap.

Along with data on printable spreadsheet pdfs (see “Results” section), I am reporting noteworthy trends, remaining limitations of our data-set, and new insights plus unanswered queries, for both farmers harvesting and rationing leaf-silages, and researchers interested in benefits to ruminants.

As yet, other farmers do not have leaf-separator machines, but some are proceeding to use tree/shrub forages fresh, dried, chipped or hand-stripped. They have been eager for the information I’ve brought to presentations; that information is updated and more completely offered herein. It’s already helping these smallest most flexible and adventuresome farmers accurately and safely improve winter diets of their herds.

Two years of immersion in data have increased my own awareness of laboratory-based understanding of ruminant digestion and needs, and further defined gaps that remain in my understanding (and some in that of other researchers). I watch my animals closer than ever, for clues about their clearer knowledge. I strive to improve how I feed my herd. There are wonderful results on some samples that my animals entirely refused, but then on certain days certain animals seek bits of those, for benefits prohibitively expensive and elusive to deduce in a laboratory.

I look forward to continuing collaborations with Wolfe’s Neck Center and Liberation Farms, where herdspeople have upped woody forage use (with maybe an extra spark from me). Karl Hallen, Tech Advisor for this Project and creator of the Leaf-Separator) continues to make plans and seek funding to develop methodology of leaf-harvest within willow biomass harvest; our ongoing contact has strengthened his own motivations. Jon Thomas Jr. and his father now have my Leaf-Separator at the Thomas Bandsaw Mills shop for winter upgrades, including less tangly cylindrical (rather than square) flail rotors plus many practical changes offered by Jon Jr. – the last bit of pay I receive from this grant (amidst reimbursements) will go to good use.

I hope our collaborative efforts will support long-term increases in vertical farm-scape diversity - trees with useful accessible canopies, pleasantly moderating farm temperatures, winds and rain. I hope also that tree-based industries soon find added-value encouragement of new forage-streams, that can strengthen sustainable, renewable land practices.

CITATIONS:

Gabriel, S (2022). SARE FNE19-930 Final Report: Quantifying Nutritionl Level and Best Practices for Woody Fodder Management in Ruminant Grazing Systems. Accessed 10/28/24.

Hanson, S. (2020a). SARE FNE18-897 Final Report: Tree Leaf Fodder for Livestock; Transitioning Farm Woodlots to “Air Meadow” for Climate Resilience. Accessed 10/18/24. https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/fne18-897/

Hanson, S. (2020b). Vermont Grass-Farmers Network (VTGFN) Mini-Grant Final Report: Lab Nutritional Analysis of Ensiled Tree Leaves and Ensiled Chipped Leafy Branches, with Dried (non-ensiled) Comparisons, plus Average Grass Fodder Comparison, and Relation to Animal Responses. Accessed 10/18/24. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1c3TVSuGlmnJTmmpE_QngsIewRG_F2Dme/view

Hanson, S. (2025). SARE FNE22-013 Final Report: Efficient Leaf-dense Tree/Shrub Silage Production from Field Edges: Climate-resilient Winter Forage Supplement for Cattle, Sheep and Goats. Accessed 5/28/24. https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/fne22-013/

Whistance, Lindsay. Farming, Animals and Trees. In Tree Fodder Virtual Seminar webinar hosted by Steve Gabriel, Wellspring Forest Farm, December 10, 2021. Accessed 1/20/25. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hCJYKhOZt58&list=PL3dng73x0WAQKUQKFWM12Ky2DkHgub7rt&index=4

Pershouse, Didi & Provenza, Fred (2020). Nourishment: Learning from the Nutritional Wisdom of Grazing Animals. Webinar “Mini-Course” 5/21/20, hosted by Land & Leadership Institute.

I farm full-time at 3 Streams Farm (my home since 2000) and Belfast Blueberry Cooperative (mountain land purchased in 2018) bringing (7 right now) dairy goats and a steer both places. My intimate involvement with trees started with professional orchard pruning in 1983. After 8 years of goat observations, I started working with tree fodders as a primary focus in 2011, presenting internationally at 2iem Colloque Trognes in 2018.

Since then I’ve been a dedicated farmer-researcher, thinking deeply about next steps as I wander with animals, rake blueberries, or pursue other mind-free tasks. My SARE FNE18-897 and 2019 VTGF projects broke ground on storage, palatability, and nutrition of Northeastern US tree leaves, and subsequent SARE FNE22-013 funded the Chain-Flail Leaf-Separator prototype, imagined by me and made by Karl Hallen (Tech Advisor for FNE24-083 to which this report pertains). That project and machine enabled production of enough leaf-silage for a 60-day home livestock trial with my very willing steer and 10 goats, plus three shorter trials at other farms, and was the source of most (but not all) samples tested for this overlapping, ongoing FNE24-083 project.

3 Streams Farm provides goats’ milk from 100% fresh greenery of woodland and pasture, to seasonal subscribers. Belfast Blueberry Cooperative provides fresh-market wholesale and PYO “No Spray since 2018” blueberries each late July-August. I am physically sustained by milk and blueberries, and rarely shop; combined gross is $12-$15,000.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

Research

1. We broadened analyses of nutrition, ensilement and digestibility to 20 tree, 11 shrub, and 1 vine species including 7 blacklisted as “invasives:”

We sent 1 or more fresh-frozen of each species, and one or more ensiled sample of most species, of machine- or hand-separated

tree leaves:

American Beech, American Basswood, American Elm, Apple, Big-toothed Aspen, Quaking Aspen, Black Cherry, Pin Cherry, Black Locust, Box Elder, Gray Birch, Yellow Birch, Green Ash, White Ash, Hybrid (Crack/White) Willow, Norway Maple, Red Maple, Rock Maple, Striped Maple, Red Oak,

and shrub leaves (plus one vine):

Arrowwood, Autumn Olive, Bittersweet, European Buckthorn, Glossy (aka Smooth) Buckthorn, Honeysuckle, Leatherwood, Multi-flora Rose, Pagoda Dogwood, Speckled Alder, Staghorn Sumac, Winterberry,

to DairyOne for:

-

“Ration Balancer” analysis which includes Moisture Content (MC), Dry Matter (DM), Crude Protein (CP), Soluble Protein (SP), Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF), Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), Non-Fiber Carbohydrates (NFC), Total Dietary Nutrition (TDN), Net Energy for Lactation (NEL), Net Energy for Maintenance (NEM), Net Energy for Growth (NEG), Relative Feed Value (RFV) and 11 minerals,

or:

-

“Basic” analysis which is same as above but with no minerals (nor SP but we added SP below), for one of the samples in each pair, as minerals don’t change much from fresh to ensiled,

We learned partway through that previous Relative Feed Value (RFV) and Non-Fiber Carbohydrate (NFC) figures were inaccurate due to lab categorizing of samples as grass forages; these were missing when Dairy One started correctly categorizing. So mid-stream I started ordering/paying for Fat EE and Ash add-ons in order for Dairy One to compute accurate NFC results (NFC though listed in initial package is included for grass forages only, as they use average known grass Fat and Ash figures).

RFV is a computation from Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF) and Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF); Dairy One sent me a calculator spreadsheet containing the formula, and I replaced missing RFV figures despite that the formula is specific to grass forages. I left these questionable figures on the “ALL” sheet, but took them off the “PAIRS” sheet.

-

Add-on measurements of Water-Soluble Carbohydrates (WSC), Soluble Protein (SP) when not included, Rumen-Degradable Protein (RDP), and Ph.

Dairy One gently requested for us to stop ordering Soluble Protein % DM (SP) and Rumen-Degradable Protein % DM (RDP) tests, because in many, the required liquid preparation gelled up and clogged their filter.

For each ensiled sample, we also obtained analysis of

-

Ammonia.

For 4 samples ensiled more than 1 year, we obtained

-

Fermentation Profiles*

*as follow-up to information from my 2020 VTGF Mini-Grant report on first-winter leaf-silages, of very low or zero amounts of the usual 6 acids found in grass and corn silages. These acids did appear with longer ensilement.

We:

a. Charted data per 32 species;

b. Computed mean and range of each nutritional measurement across per-species avegares of 10 most prevalent species;

***See bottom of “Nutritionl Data from All”spreadsheet, in the Results section ***)

c. Computed mean and range of changes in each nutritional measurement from fresh to ensiled, across species;

***See top of “Paired Fresh & Ensiled” spreadsheet, in the Results section.***

d. Re-grouped Fresh/Ensiled Pairs into 3 harvest-date categories. Computed mean and range of changes in each nutritional measurement from fresh to ensiled, per date category, to look at effects of length of period ensiled (but even these changes are affected by date-related differences in initial fresh leaf carbohydrates especially). I also compiled fresh and ensiled data separately per date-period, on same sheet, to look for date differences attributable to leaf development of fresh samples, and to allow others to puzzle over the complete data-set.

On separate spreadsheet, I re-grouped selected data of 3 species having multiple harvest-dates, into 3 harvest date-periods. I noted trends of change for each nutritional measurement as leaves matured and changed, while length of remaining warm weather-period supporting fermentation decreased.

Both of the above harvest-date category spreadsheets looking simultaneously at these two factors can help farmers to think about their choice of dates to harvest/ensile leaves, but do not offer conclusive results due to differing richness of our 3 sites, with each site harvested at a different point in the growing season.

Differences in average harvest dates of 2022-’23 versus 2025 sets of matched fresh/ensiled pairs provide another glimpse of harvest date effects.

***See “Fresh/Ensiled Pairs Comparing 3 Date Categories” spreadsheet, “Selected Leaf-samples Comparing 3 Date Categories” spreadsheet, & 1st 2 pages of “Dairy One 2023-2025 data comparing PAIRED FRESH & ENSILED leaf-samples, Final” spreadsheet (inc my comment at top of 2nd page), all under “Results.”***

e. Discussed protein availability in light of CP, SP, RDP, & Ammonia measurements, including change from ensiling, plus considered probable increase in utilization due to Condensed Tannin levels. (See Protein discussion under “Results.”)

***Find links to all (printable PDF) charts in the “Results” section.***

2. We broadened toxin testing with ensiled comparisons.

We used existing fresh-frozen/ensiled sample-pairs (for immediate March 2024 results), plus harvested, leaf-separated by machine or by hand, packed new samples, & obtained laboratory analyses for:

a. Cyanide (HCN, also known as Prussic Acid) in 22 cherry leaf-samples:

-

6/27/23 Black Cherry (MOFGA), 1 Fresh/1 Ensiled 120 days;

-

6/29/23 Pin Cherry (MOFGA), 1 Fresh/1 Ensiled 120 days;

-

10/11-12/23 coppiced Black Cherry (Wentworth Way, Y Knot Farm), left out 24 hrs on a gray day, 1 Fresh/1 Ensiled 30 days;

-

May 21, 2024 Black Cherry (Y Knot Farm mature tree), Fresh;

-

June 3, 2025 Black Cherry (Y Knot Farm mature tree), 1 fresh & 1 dried;

-

1 fresh sample July 13, 2025 Choke Cherry (Harriman Rd., Swanville, ME), Fresh;

-

July 3, 2025 Black Cherry (3 Streams Farm small pollard thicket) selecting leaves from new growth only, 4 samples: Fresh, Ensiled 30 days, Ensiled 60 days and Ensiled 90 days;

-

July 3, 2025 Black Cherry (3 Streams Farm small pollard thicket) selecting leaves from new growth only, Wilted 4 hrs (new growth portions left out mid-day in full sun, before hand-stripping leaves), 4 samples: Fresh, Ensiled 30 days, Ensiled 60 days and Ensiled 90 days;

-

July 3, 2025 Black Cherry (3 Streams Farm small pollard thicket) selecting leaves from new growth only, Wilted 24 hrs (new growth portions left out mid-day in full sun, then brought into the house for rest of wilting-period before hand-stripping leaves), 4 samples: Fresh, Ensiled 30 days, Ensiled 60 days and Ensiled 90 days.

We summarized findings, with inclusion of 2022 sample-pair tested within FNE22-013, & made recommendations/warnings for use of fresh, ensiled or dried cherry leaves.

I collected a 12-sample set of Y Knot Farm Black Cherry in 2024, but double zip-lock bags of ensiled leaves leaked air and molded (unlike previously purchased zip-lock bags used to ensile late-season leaves for nutritional testing). So I packed all 2025 samples excepting the Dried sample in plastic jars with foam lid-liners. All 2025 samples were frozen until October FedEx Overnight sending.

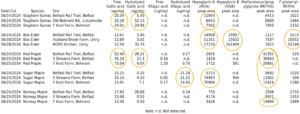

b. Gallic Acid and Ellagic Acid both free & hydrolyzed* quantitative levels, Hypoglycines A and B, plus homologues Methylenecyclpropylglycine (MCPrG) and γ-glutamyl-MCPrG comparative levels, in 3fresh replicates (similarly aged, with similar sunlight, but differing locations) each, of 5 species:

Red Maple, Rock (Sugar) Maple, Norway Maple, Box Elder, and Staghorn Sumac.

We:

-

Compared toxin levels between above species,

-

Explored relationship to ruminant intake data from SARE FNE22-013 livestock trials plus additional sampling/feeding observations in 2024-’25,

-

Searched literature on this obscure subject, turning up info on potential ruminant digestive benefits from Gallic and Ellagic Acids, and an absence of info on toxic thresholds (especially in light of multiple toxins per species, and most of our data being relative levels versus absolute quantities).

Due to misunderstanding of listed gallotannin lab-service at UC Davis, which is non-quantitative and only on horse urine, we re-allocated funds for 3x greater expense of higher-tech analyses at MU Metabolomics Center. There, Director Zhentian Lei advised me to include Ellagic Acid (EA), and to use triplicate sampling (so we let go of including less abundant Striped Maple, and let go of ensiled comparisons, due to expense). I had already added the Hypoglycins and homologues due to their presence in Box Elder and maple literature.

*11 of 15 free Gallic Acid (GA) figures are much higher than hydrolyzed figures. Zhentian Lei had advised that hydrolization would yield data on Total level, but afterwards responded that some Free GA must have evaporated during hydrolysis. (2 Free Ellagic Acid (EA) figures were also higher than hydrolyzed figures).

***See “Maple, Box Elder & Sumac Toxins” group of files under “Results.”***

We summarized our data and literature-based information, plus my memory of comments of farmers who use these 5 species, and my own animals’ use or rejections including provision of off-farm Box Elder and Staghorn Sumac in 2025, to give some idea of forage usability.

These toxins are said to increase throughout the season. Our “straw-payer” at University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry expressed unwillingness to wait; hence our rather early June 24-25, 2024 sampling dates. (MU Metabolomics Center can only directly serve those with university and other official research organization accounts.)

***See 2 “Maple, Box Elder & Sumac Toxins” files under “Results,” for charts and graphs created by Dr. Zhentian Lei, MU Metabolomics Center; I’ve made minor additions and one correction. ***

3. We obtained 1 nutritional analysis per each tree/shrub-species layer or full barrel/bucket of leaf-silage (Black Cherry, Gray Birch, Honeysuckle, Quaking Aspen, Big-Toothed Aspen, Red Maple, Red Oak, White Ash, Green ash) fed during our 66 day winter SARE FNE22-013 goat/steer trial (which measured dietary intake and milk yield), plus obtained analyses on each other ensiled date-batch of those species, and on other less abundant tree/shrub species fed before or after that trial plus fed within trials at Y Knot and Faithful Venture Farms.

We took 3 lbs per numbered barrel fed, drawn from near top, middle and bottom of each barrel, then mixed/bagged/froze 2x1 qt and 2x tiny- bag (2”x3”) samples. We drew/packed/froze lesser amounts from each bucket fed. We sent 1 or more sample/harvest-date/tree or shrub species for DairyOne analyses including:

-

“Ration Balancer” analysis which includes Moisture Content (MC), Dry Matter (DM), Crude Protein (CP), Soluble Protein (SP), Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF), Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), Non-Fiber Carbohydrates (NFC), Total Dietary Nutrition (TDN), Net Energy for Lactation (NEL), Net Energy for Maintenance (NEM), Net Energy for Growth (NEG), Relative Feed Value (RFV) and 11 minerals, and

-

Add-on measurements of Water-Soluble Carbohydrates (WSC), Soluble Protein (SP) when not already included, Rumen-Degradable Protein (RDP), Ammonia, and Ph.

We charted, examined and are reporting:

a. Mean of each nutritional measurement per tree/shrub species;

b. Relationships between animal intake and nutritional measurements per tree/shrub species;

c. Nutritional comparison of these (mostly) 2023 leaf-silages to Dairy One average grass-hay and grass-silage figures 2004-2024, and to 2 samples of 2023 hay (from 2 sources), that we fed out during the 3 Streams Farm trial. (See “All” spreadsheet under “Results.”)

Based upon this nutritional and toxin data, standard nutritional requirements, and Animal Intake data from FNE22-013 3 Streams Trial, we:

-

Are offering supplemental leaf-silage rationing impressions per ruminant species, with discussion of gaps still missing for full understanding of these complex forages; and

-

Have described harvest developments that must occur in order for this clearly valuable forage to become feasibly usable on a broad scale.

4. Updated, improved and used our website, “tree fodder” listserve, and network of livestock farm-related organizations, to streamline provision of this critical alternative forage data, augmenting in-person presentations at farmer events.

-

Emily MacGibeny created a new 3streamsfarm.wixsite.org/3streamsfarm website built of pdf windows and download buttons, so I Shana can keep and update each page as a pdf of a Libre Office Presentation, enabling me to do that work on browse wanders off-line, with full control of color backgrounds and content organization. We added recently-dated tree fodder resources, and pertinent links (to updated spreadsheets, photos etc) in summaries of each of my research studies.

-

Emily went through my Google Drive and deleted duplicate files plus files I'd unintentionally uploaded, and then organized into folders, with room to spare for future Resource additions. Previously my Google Drive was hitting full storage capacity, preventing me from posting links to new resources on our website.

-

Emily MacGibeny went through our Tree Fodder listserve, adding the last few years of contacts from my paper notes from presentations and phone calls plus from saved emails. I remain unable to send emails to this listserve myself (my Proton enail does not have have listserve enabled, and the gmail we use for that has invisible black buttons on my black screen). I soon will have another new resident who is likely to have that skill. Emily sent out notifications of presentations at key moments, during this Project.

NUTRITIONAL ANALYSES

Dairy One (Ithaca, NY) completed nutritional analyses on 102 leaf-samples of 20 tree, 11 shrub and 1 vine species. I organized results by species (except for one European Buckthorn sample paired with a same-day, same- site Smooth Buckthorn sample for comparison), with fresh-frozen versus ensiled paired samples listed at top of each species-specific list, and following samples generally organized consecutively by harvest-date. A later-season date = shorter ensilement; we froze most ensiled samples during 2023-’24 winter feed-out, including those harvested in fall of 2022 when our Leaf-Separator machine first arrived (therefore the 2022 barrels and buckets had the longest ensilement period, with a few warm-enough fall weeks plus one full summer).

Our Species averages of each nutritional measure use ensiled samples only, for consistency, and are only computed when multiple ensiled samples of a species were tested; we tested just one fresh sample for most species, and fresh/ensiled paired samples repeat the same batch. Averages are below species-specific lists containing multiple batches, and averages of 10 most abundant species are also compiled and averaged across species on the last 2 pages..

Dairy One NUTRITIONAL DATA from ALL 2022-'25 LEAF-SAMPLES (For compilation of 10 most abundant species averages, go to END) (pdf formatted to print on legal-sized, landscape-oriented paper.)

Previous Northeastern nutritional data on tree and shrub leaves was scarse, and nonexistent for ensiled leaves; our results are therefore highly useful despite sampling limitations. My caveots describing limitations follow:

These results are specific to Waldo County, Maine, and most samples came from just 3 SARE FNE22-013 harvest-sites, with varying and sometimes low numbers of samples per species. That harvest, which produced most of our samples, was aimed at yield per lineal feet of field edge, labor-time measurements, and provision of many barrels-full for livestock trials in that project. We tested one fresh and one ensiled sample from each species that we came upon (we missed sampling a few), and tested one sample from each barrel, bucket or date-batch later once ensiled. Quaking Aspen averages for instance represent multiple samples from one stand only which produced many barrels – on retrospect I have regrets about our 3 Streams Farm Trial per-barrel test allocation decision, which left limited funds to test other species, harvest dates or sites.

We did not plan nor commit to a broad randomized sampling design for regionally generalizable results, as that would have taken dedicated driving and sample-packing time beyond our budget and availability; rather our project utilized the “bird in hand” of leaves already harvested, with just a small number of samples added to fill out our species list.

Validity of comparisons of species averages is limited by differing site qualities and differing harvest date-windows at the sites. The Leaf-Separator machine farm-trailer base required slow transport-speed, so was parked at sites consecutively with just one return-trip to Y Knot Farm. (As I write this report, Jon Thomas Jr., Thomas Bandsaw Mills, is squaring/aligning the frame and wheels of that farm-trailer base to handle normal road speeds, in future!)

Dry Matter (DM) across all individual samples 2022-2025 including trees and shrubs both fresh and ensiled averaged 40%.12 (mostly fresh) shrub samples added in 2024 and 2025 (close to half of our 26 total shrub samples) had a much earlier average harvest date than did 2022-’23 samples; earlier sampling dates seem to correlate with lower DM, and pulled our average DM down from previous calculations.Lowest among these were 6/3/25 fresh Pagoda Dogwood with 20.6% DM, and 7/31/25 fresh European Buckthorn, shaded by mature trees in a stream flood zone, with 20.8% DM. Our (mostly MOFGA-site ensiled) Honeysuckle samples ranged 25-55% DM, with unclear date correlation. Tree samples ranged less than that within species, but just as widely across all species. 10 tree-leaf samples (of 86) had DM above 50%; 6/26/23 Box Elder (the only Box Elder sample we used for nutritional testing) had the lowest %DM of our tree samples, with 23% DM fresh and 22% DM ensiled.

DM content affects how much one must harvest, to meet needs of one’s animals. Traditional harvests of pollarded trees in Europe occurred during late summer into fall, when DM is high, and tree carbohydrate stocks are also high (carbohydrates are needed for tree recovery and health, as well as for forage value). Here are my laborious DM and Harvest Date computations, to make sense out of our less than consistent data sets (which as stated above were aimed at bulk harvest versus sampling):

% DM & Harvest Date Aves of Leaf-Sample Groups (<-- pdf link, in case above screenshot is not clear)

Protein: Crude Protein (CP %DM) levels in our leaf-silages were respectable, falling between those of the 1st- and 2nd-cut hay we had that winter. Both 1st- and 2nd-cut hays were cut in late August, due to 2023 wet June and July; the bulk of our leaf-silages were harvested late June through July, and then a lesser number of barrels late September through to October 12th. Early cuts of both grass and tree matter are known to have higher protein levels as % of DM, than later cuts. Yet I wondered t owaht degree higher moisture/lower DM at earlier dates accounted for this difference.

2025 harvest-dates were 6/3 to 7/7 with a mid-June average date, an earlier range than 2022-’23 6/25 to 10/6 dates with mid-August average. Because DM and fiber were lower in these earlier-dated 2025 samples (by 6-7% & 5-8% respectively), I computed protein levels AS FED, below: This showed that difference in %DM protein levels between these sample-groups does not change how much volume animals must eat to get their protein. AS FED, the protein-levels differ little.

Acid Detergent Insoluble Protein (ADICP) levels in my 2019 leaf analyses had indicated limited protein availability (as do our new results). We therefore ordered quantification of Soluble Protein %CP (SP) and Rumen-Degradable Protein %CP (RDP), to gain more clues about protein utilization. In many of these tests, the required liquid preparation gelled up and clogged the lab’s filter. After the first large batches of samples yielded much but not all requested data, I gave in to Dairy One’s gentle suggestion for us to stop ordering SP and RDP tests.

We have complete SP and RDP data for all samples of 16 species (out of 26). SP and RDP tests failures happened on all 5 Red Oak samples, and on fresh/ensiled sample-pairs of American Elm, Norway Maple, and Smooth Buckthorn, such that we have no measurements for these 4 species. Either SP or RDP failed on 4 out of 5 Honeysuckle samples; RDP failed on 4 out of 7 Quaking Aspen samples, 1 of 6 White Ash samples, and 3 of 11 Black Cherry samples. All of the first 3 SP tests and 2 of the first 3 RDP tests failed on Gray Birch, such that we have no SP and only one (curiously high) RDP result on Gray Birch; Red Maple had this problem for 3 of 6 SP and 4 of 6 RDP tests.

To compare actual quantities in the feed, I computed SP %DM and RDP %DM for both leaf- and grass-forages. Average SP %DM levels in our Black Cherry and Green Ash samples were highest among our tree samples (2.75 and 2.73 %DM respectively), slightly surpassing the level in our 1st-cut hay; certain samples of White Ash, Quaking Aspen, Basswood and Box Elder had similar levels. RDP levels were also highest in Cherry and Green Ash, but lower than that of the 1st-cut hay.

Our three Autumn Olive samples surpassed all other tree and shrub species, with CP ranging from 21 to 26.4 %DM, SP ranging from 4.8 to 9.5 %DM, and RDP ranging from 10.5 to 17.7 %DM. For comparison, Dairy One average grass hay has 11 %DM CP, 3.7 %DM SP and 7.2 %DM RDP, and average grass silage has 15.5 %DM CP, 8.2 %DM SP and 10.9 %DM RDP. Among the few shrubs with complete protein tests, a 6/3/25 Pagoda Dogwood sample also had respectable protein levels.

Jaime Garzon,UME Cooperative Extension Forage Specialist, uses a practical guideline that WSC to CP ratio should fall between .4 and 1.5 in silage, for digestive balance. Of that CP, he says SP should be 30-40%. Our average Black Cherry silage falls well within that WSC/CP range at .65, but with SP at only 20% of CP. Our Green Ash ratio is .575 with SP at 22%. Our 2 lowest-protein Autumn Olive samples come closest, with average WSC/CP ratio at .45 and SP averaging 25.5%. (We unfortunately did not obtain a WSC level to do this math on the much higher-protein early-harvested sample.)

Condensed Tannins (CT) in our leaves are likely to be increasing protein utilization of all feedstuffs consumed by as much as 25%, according to Wayne Zeller’s ongoing work on our leaves (described below) combined with studies of cattle performance when fed other sources of CT. CT at 3% DM is optimal; more is anti-nutritional and antifeedant. Our levels are similar to those in Birdsfoot Trefoil (BFT); high-CT BFT fed as 60% of dietary DM to dairy cattle falls well below the anti-nutritional level, and increased digestive efficiency and milk production (Hymes-Fecht et al. 2013).

PDF, Birdsfoot Trefoil Silage increases Production of Lactating Cows, Hymes-Fecht et al. 2013

According to MOFGA Grounds Director and farmer Jason Tessier, Tessier farm, many grass-based farmers in Maine like himself make early wrapped baleage, and/or grass silage in a bunker. These early cuts have a surplus of protein, making energy versus protein the limiting nutritional component on such farms. See discussion of high NFC and WSC in our leaf-silage, below (past the Fiber discussion).

Quality of Protein: Tech Advisor Karl Hallen had a thought as we edited this report: Amino Acid profiles of grass forages do not fully meet Amino Acid needs of animals; perhaps woody forages might have more complete protein. We looked and found little info on Amino acids in Northeasatern leaf-species. Mulberry leaves in China DO have a more complete array of Amino Acids than does grass (Jiang & Nie 2015, cited in Mulberry FeedValue - Trees for Graziers ).

Acid Detergent & Neutral Detergent Fiber (ADF and NDF) % of DM, averaged across averages of our 10 most abundant species of leaf-silage with August 9th average harvest-date, were respectively 70% and 66% of Dairy One averages of levels found in grass silage. Ensiled samples of matched (fresh/ensiled) pairs that were harvested in 2025 had earlier average harvest-date of June 17th, and had only 56% and 54% of ADF and NDF levels in grass silage (plus had more shrubs/less trees but that has less effect on %DM than does date).

Our leaf-silage leans somewhat toward the “concentrate” end of forages; low fiber correlates with high energy (see NFC, Fat EE and NE discussions below). In our SARE FNE22-013 trial, when 10 goats and a steer ate 55% and 33% (respectively) of their diets as leaf-silage (in a 100% forage diet, leaf-silage plus poor quality 2023 1st-cut hay), animals were satiated with 97% of the total lbs. DM that they ate when given 2nd-cut hay in place of that leaf-silage proportion. Strangely, this percentage of less DM intake with leaf-silage is the same for the steer and goats, despite that the goats were eating a much greater proportion of leaf-silage. What need was the steer meeting with his 33% leaf-silage diet, that allowed him to eat less DM? (Or is that difference simply accounted for by higher moisture in the leaf-silage than in hay? That seems unlikely to me.)

Leaf-silage or 2nd-cut hay were only offered once per day for 2 hours. If I’d had enough to offer a second such free-choice meal-period per day of leaf-silage, I suspect that they might have eaten that much again (but that would bring goats above capacity – very wide and giving more milk?).

If the steer ate twice as much leaf-silage, he would be eating 67% of his lbs. DM as leaf-silage, and would probably be satiated with 86% of the total lbs. DM that he ate when given 2nd-cut hay once per day and no leaf-silage. This level of leaf intake for a bovine would be far above modern expectations (Lindsay Whistance says cattle choose 12% of their diet as woody forages: Whistance 2018), yet up until the mid 1700s European cattle were indeed wintered on more leaves than grass, with 100% leaf cattle-diets in winter a probable reality for thousands of years, in earlier historic times.

Non-Fiber Carbohydrates (NFC): At 38.8% of DM average across 10 most abundant leaf-silage species’ averages, our leaf-silage had well over twice the NFC of Dairy One average grass-silage (at NFC 16.8% DM), and surpassed average grass-silage level of

Water-Soluble Carbohydrates (WSC), the most quickly digested component of NFC: WSC in our 10 most abundant leaf-silages averaged about 10% DM; Dairy One grass silage average is 8% DM.

Such concentrated energy means that leaf-silage can support reduced use of off-farm-sourced concentrates, particularly when other dietary components compensate for lower protein levels, or if the leaf-silage is Autumn Olive, or some other higher-protein species.

Fat Ether Extract (Fat EE) level in our leaf-silages averaged 6% DM, or 150% of that in average Dairy One grass-silage.

Hauge, Garmo & Austad (in Austad & Hauge 2014) wrote (my English notes from the Norwegian – thank you to Yvonne Taylor, past Black Locust Farm farmer, for translating to me a few years ago) :

“The fat content is high in leaves (5 – 7% DM), as compared to grass (1 – 3%). The reason is that the leaves have a thick, protective layer. This layer serves as a defense against parasites, and reduces water loss as a result of transpiration in the plants. The outermost part (cuticle) is built from a cutin and wax that doesn’t have any nutritional value. Leaves from birch often have a higher content of fat than leaves from willow, vier, or, aspen, and rowan. The least fat content is found in elm, ash, linden, and hazel. Like in grass and clover (trifolium species) it is linolensyren [Linolenic acid, ALA] that is most prevalent in leaves (35 – 45% of total fatty acids) (Garmo 2012).”

In light of this, our leaves should have around 2.4% DM Alpha-Linolenic Acid.

Ensiled leaves consistently had more fat than fresh leaves (averaging 111% of fresh DM level, or 106% of fresh level As Fed). See "Nutritional Changes from Fresh to Ensiled" below.

Yulica Santos Ortega identified hundreds of lipids in our goats’ milk with and without tree/shrub leaf-silage, during the SARE FNE22-013 3 Streams Farm trial. (I would love to know more about health effects of those lipids on us milk drinkers – Yulica said the lipids are “all good.”) Yulica wanted to look at leaves eaten, but then moved to an all-consuming new job at University of Virginia. I have leaf-silage samples frozen, tallied by dates fed, in which to identify leaf lipids (to match our known lipids in milk samples, more milk samples are also frozen). Such further research might detail benefits of high leaf Fat content to animals.

Fats in ruminant diets increase digestive efficiency and decrease methane production, with no ill effects on digestion of up to 6-7% Fat in DM of diets (Hassan et al. 2020). It intrigues me that these optimum levels cited match content in our leaves; as usual, thousands of years of ruminant consumption of leaves can't be very wrong. : )

Metabolizable Energy (ME) signifies how much energy is available to animals for all bodily functions, and is used to compute Net Energy figures below.

Net Energy (NEL, NEM and NEG) across averages of our 10 most abundant species of leaf-silage averaged scores of .66 for NELactation, .64 for NEMaintenance, and .38 for NEGrowth. These were higher than levels in either of our hay samples or in Dairy One-tested average grass hay (across better years than 2023). Our NE figures even surpassed those of average Dairy one-tested grass silage levels (.58, .59 & .33). Our leaf-silage .66 NEL fell squarely halfway between Dairy One’s NEL averages for grass silage and corn silage! The steer Angelo, who was 2 years old and growing, skipped to his leaf-silage offerings. Despite NEM still being low in his forage-only diet (though better with the leaf-silage), he seemed to grow fine – perhaps the Condensed Tannin magnification of protein utilization (see Protein discussion above) helped.

Minerals varied widely in our leaf-silages, as did those in my 2019 samples*, with a trend of higher levels of key elements than in grass forages. (*2020 testing thanks to a Vt Grass Farmers Network Mini-Grant; that report, Hanson 2020b, linked here & fully referenced in "Introduction" above, includes a more in-depth look at mineral levels in leaves and livestock needs.)

Calcium was high in our leaf-silage species-averages, ranging from similar DM levels to both our hay samples, to almost 3x as much as in the hay. Across our 10 species-averages, Calcium DM level averaged to be 1.75% of that in average Dairy One-tested grass silage. I suspect that my lactating goats (and possibly my growing steer as well) preferentially choose forages that are high in calcium.

Zinc was especially high in both Aspen species, with DM levels in the two ensiled Y Knot Farm Big-toothed Aspen samples averaging 273.5 ppm, and 5 of 6 ensiled MOFGA Quaking Aspen samples averaging 143.2 ppm (6 of 6 samples averaged 126.7, but I am tempted to discredit the sample with 28 ppm, harvested amidst all those samples from one stand of trees). Across our 10 species-averages, Zinc averaged 74.6 ppm, just about twice the 37.8 ppm average level in Dairy One-tested grass silage.

During our SARE FNE22-013 trial, I did not feed animals any ensiled rockweed that I harvest (into barrels, from rocks along the shore of Penobscott Bay at low tide) and usually offer intermittently. That seaweed and a salt block (which I did provide during our trial) are my animals’ only mineral supplementations, excepting dirt that especially the steer eats from upturned tree root-masses (no such root-masses were present in their Winter Trial paddock). I have at times in past tried offering mineral mixes to my goats, but they showed no interest, perhaps because of their high browse and tree matter diet.

If rations include a broad species-range of leaf-silage, free-choice intake of mineral supplements may decrease, or such suplements may become unnecessary.

Note when looking at Ash and Mineral figures of our 2nd-cut hay that it was full of dirt from that rainy 2023 season, with minerals that my animals left in the offering-sled. (Our leaf-silages include no dirt.)

Fermentation & pH: In past I was confused by low 3.7 pH of spring-harvested Beech leaf-silage with almost no fermentation acids detected in any of 5 samples tested (Hanson 2020b, linked above). I thought that perhaps different acids were produced (possibly that acidity was from Vitamin C, already present when leaves were fresh?). So we decided last summer to send 4 samples ensiled for more than a year; the usual fermentation acids did appear. PH went down from fresh to long-ensiled (over 1 year) 1.1 points in Big Toothed Aspen (going from 5.5 to 4.4), zero in July-harvested Beech (which stayed at 5.4 with very low .4% total acids), and 1.5 in Winterberry (going from 5.7 down to 4.2, the acceptable upper limit for grass silage. In the first winter as fermentation slowed, pH was 5.4). Across these three sample-pairs (Beech, Big-Toothed Aspen & Winterberry), fresh pH averaged 5.53, and 1+year ensiled pH averaged 4.67.

The animals consistently mobbed our pleasant-smelling 1+ year-old leaf-silages of palatable species and ate them, as they did in the first winter.

Dairy One FERMENTATION PROFILES & Nutrition, comparing 2018 short fermentation and 2023-'24 1 yr+ fermentation (pdf formatted to print on legal-sized, landscape-oriented paper)

Nutritional Changes from Fresh to Ensiled

We had Dairy One analyse nutrition in 24 matched fresh/ensiled sample-pairs of 23 species = 6 shrub plus 17 tree species (we included two pairs of White Ash, with much healthier-looking leaves from the site with later harvest-date, hence duplication), to look at nutritional changes when ensiled. My summary of most notable changes follows:

Dry Matter (DM) decreased slightly with ensilement, such that both types of

Acid Detergent and Neutral Detergent Fiber (ADF & NDF) both went slightly up as % of DM when ensiled, but since DM decreased, fiber % AS FED stayed stable.

Crude Protein (CP) went up slightly (whether considered as % DM or % AS FED). Within CP,

Rumen-Degradable Protein (RDP) %DM decreased to 95% of Fresh average, which indicates that the increase in CP consisted of rumen-escaping protected proteins. Within decreasing RDP,

Soluble Protein (SP) %DM increased to 103% of the Fresh average. So Rumen-Degradable Insoluble Protein was what decreased, as CP went up as a whole with more rumen-protected protein plus more soluble protein. (I realize I am be-laboring this, and also that my use of SP %DM versus %CP is unconventional, but I am trying to visualize complexity of the changing amounts).

Water-Soluble Carbohydrates (WSC) %DM dropped by 34.5% of fresh level on average when ensiled, across all paired samples,and

Non-Fiber Carbohydrates (NFC) %DM as a whole dropped by 10% of fresh level; this is mosty accounted for by the drop in WSC, within NFC(so mostly sugars, and not much simple starches, probably got used up by acid-producing microbes).

Fat Ether Extract (Fat EE) went up. Fat content in ensiled samples averaged 111% of % DM levels (or 106% of % AS FED levels) in matched fresh leaf-samples (across 20 sample-pairs with full Fat EE data). Higher Fat level was fairly consistent across samples; only 2 pairs had higher Fat % DM fresh, or 3 pairs had higher Fat % AS FED fresh, versus ensiled, out of 20 pairs.

This rise of Fat when leaves are ensiled intrigues me; tree physiologist Kevin Smith, UNH Extension, Durham, said it can only happen in aerobic conditions (does it happen immediately upon sealing the barrel?) Perhaps the rise is in wax coatings, as the leaves suffocate? Do the wax coatings eventually break down through fermentation to become digestible fats?

My animals like most ensiled leaves as well as they do the same fresh, accepting even aged offerings even in summertime, when they wander plus graze pasture. Retired UMaine Cooperative Extension forage specialist Rick Kersbergen once told me “It’s all downhill, from fresh.” Maybe so, but it’s not a steep hill.

Dairy One 2023-2025 data comparing PAIRED FRESH & ENSILED leaf-samples (pdf formatted to print on legal-sized, landscape-oriented paper)

Harvest Date Effects

I divided our Fresh/Ensiled sample-pairs into 3 harvest-date categories, to look at the interaction of said-to-be lower protein at later harvest-dates, less warm weather left for fermentation in those harvested later, and any other observations related to date. Both comparison spreadsheets below have limited validity due to differing harvest-sites per date-period. The 1st and 2nd pages of the original "Dairy One data comparing PAIRED FRESH & ENSILED leaf-samples" spreadsheet ABOVE are actually as informative, with differing harvest-year groupings averaged across samples. (Different harvest-year groupings of Fresh samples especially have different average harvest dates, with 2025 having the earl;iest. Please refer to the "% DM & Harvest-Date Averages" sheet further above, included as a photo and also a link to pdf, to cross-refererence harvest-date averages for different harvest years.)

Dairy One PAIRED FRESH & ENSILED samples, HARVEST-DATE categories COMPARED (pdfs above & below are formatted to print on legal-sized, landscape-oriented paper.) Selected leaf-samples comparing 3 HARVEST-DATE categories

TOXIN ANALYSES

Cyanide in Cherry Leaves

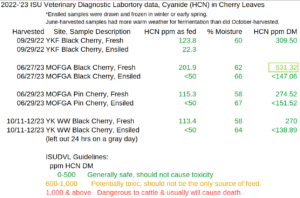

Initial results: Cyanide (HCN) tests on 4 fresh & ensiled sample-pairs, 3 of Black Cherry and 1 of Pin Cherry, from our 2022-2023 harvests showed very safe reduction of Hydrogen Cyanide with ensiling. Even fresh levels were below the toxic threshold.

2022-'23 ISU VDL data, Cyanide in Cherry Leaves, 4 Fresh & Ensiled Pairs (<-- pdf link, in case above screenshot is not clear)

Struggles for a Cherry-leaf set with all treatments: In 2024 I made a full set of Y Knot Farm black Cherry samples with all combinations of fresh, wilted, and ensiled, but used double zip-lock quart freezer bags to ensile. This had worked for late-harvested 2023 samples in a basement, but these early-harvested ones in my warm house leaked and molded (the bags also seemed thinner with different texture – did they change design?).

In 2025 I collected samples on May 21st and June 3rd from mature Black Cherry trees at Y Knot Farm that were similar to those we harvested there in 2022 and ‘23. Such early-cut cherry leaves are reported to be more toxic, as are wilted leaves. June 3rd to 4th, I packed my 3nd try at a full matched array of 12 samples: fresh, ensiled 30 days, ensiled 60 days, and ensiled 90 days, then after branches wilted for 4 hrs in the trailer, 2 similar sets of 4 but first leaving one set to wilt for 4 hours and the other for 24 hours, before packing and sealing, this time in plastic wide-mouth laboratory containers with foam lid-liners (that worked). I also made a Dried sample from same harvest, but unfortunately packed that in bags (why that mattered becomes evident, if you read far enough into my typing).

All spring I was also collecting sample-pairs for Wayne Zeller’s C Tannin work, and the ensiling ones for both purposes cluttered my cupboard, such that I did not notice my oversight of the 4 hrs wilted “fresh” Black Cherry sample, that had gotten in there instead of directly into the frreezer (my farm gremlins are interested to participate in anything I do here).

So on July 3rd I harvested my own stand of small Black Cherry pollards, selected new growth sprouts for higher Cyanide content (since the date was late), and made my 3rd try at a complete set of 12 samples that day and the next (again in plastic laboratory jars, and this time all made it into the freezer on designated days as planned!). I ran brush with remaining leaves of older growth through the Chain-Flail Leaf-Separator, to almost fill one barrel (a winter treat for my animals).

I did not have a protocol of weighing samples for equivalent air inclusion, and on retrospect should have done this. A few samples had a piece of bubble-wrap inserted at top to take up a bit of extra space (when leaves from each treatment were running out) - instead of a piece of paper that I use to make sure leaves don’t get under the sealing edge - and I failed to note which ones had that extra space with bubble-wrap.

It is a daunting and pressured task for one farmer (whose animals rely on me wandering with them most of every day, and/or climbing trees) to get all those samples harvested then hand-stripped and packed, at right stages of wilt across two days. Choosing to up Cyanide potential by using new growth only precluded use of the SARE FNE22-013 Chain-Flail Leaf Separator, and even when I do use it, I remove sticks and twigs further by hand. Each quart jar packed tightly with leaves and labelled took me about a half hour, so the “wilted 4 hrs” and “wilted 24 hrs” are approximate.

A barrel of Black Cherry leaves from my sampling harvest, & Observations: On December 24th and December 25th, I fed that barrel of older-growth leaves from the July 3rd harvest to 7 happy goats and the steer, Angelo.

Angelo ate a good quantity from a sled, for about ½ hour, then took a hay and water break, came back to eat more and I’d passed it to the goats. So he asked for me to open the barrel, which I did. The second day he had a sled-full and took the same break – can he sense Cyanide? I sent in no test of those older leaves (I wished to, but was already sending more tests than the grant funds were covering). The 7 goats did not have enough between them, so ate all straight up.

An animal can eat the toxic dose in a day and be fine, if they do not eat it all at once; Cyanide acts quickly, but then also exits the body quickly (at least when not fatal).

During our SARE FNE22-013 winter 2023-’24 trial, my animals ate free choice amounts of ensiled Black Cherry during 2 hr offering-periods, but with 2 other leaf-silage species simultaneously offered – except on one day (February 7th, the 5th measurement day of 7 in the last trial-rotation, when barrels were almost gone). That day, goats got just 2 species, Quaking Aspen and Black Cherry. Angelo was entirely refusing Quaking Aspen, so he ONLY got Cherry; he’d had one previous day like that (also in last rotation, when goats got Cherry along with Quaking Aspen and least palatable Gray Birch). Both those days Angelo was offered 14+ lbs as fed; on the earlier date, he ate 11.5 lbs and on the latter 9.25 lbs as fed; the 1st barrel (#9, harvested 6/30/23 and packed 2 days later in gray weather at MOFGA) had 40.3%DM, and the 2nd (#46, harvested and packed on 9/2/23 at Y Knot Farm) had 41.9%DM, so he ate 4.63 lbs DM and 3.88 lbs DM of ensiled Black Cherry leaves, respectively.

2 to 2.5 mg Cyanide per kg body weight is considered a fatal dose. Some Cyanide levels in my 2025 samples below, ensiled in small jars versus barrels, hand-stripped rather than machine-separated, frozen at lower temperatures than barrels outdoors, and with new growth selected separately from old, would have been sufficient to kill Angelo twice over, if levels were as high in Black Cherry leaf-silage that he ate so well on each of the above-discussed winter 2023-’24 trial days.

I saw my animals for the first time sparsely eat (versus gobble) fresh-cut Black Cherry from a lightly pollarded tree in their pasture this past early summer (2025). They did finished all leaves within a day. I really do conjecture that they know when to stop eating. Susan Littlefield, Y Knot Farm, has bountiful Black Cherry pollards and observes similar behavior in her milking sheep.

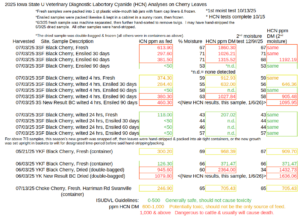

2025 (strange) results: After a busy summer, I finally sent the July 3rd, 2025 frozen multiple-treatment 12-sample set, 2 Fresh samples with 5/21 and 6/3 harvest-dates, a matching Dried 6/3/25 sample, all Black Cherry, plus 1 Fresh 7/13-harvested sample of Choke Cherry, to Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (ISU VDL), and received results in October. Those results were not what either Scott Radke, ISU VDL Toxicologist and Director, nor I expected.

2025 ISU VDL data, Cyanide in Cherry Leaves, updated (<--pdf link, if screenshot above is not clear)

2025 ISU VDL Cyanide (HCN) results had one trend opposite of expected, and two sample results that were extreme exceptions to expected patterns. The fresh 7/3/25 sample, with leaves selected from new growth sprouts only, had higher Cyanide than did the same “wilted 4 hrs,” and then “wilted 24 hrs” had even less.

Perhaps the samples dried somewhat versus wilting; wilting is supposed to increase Cyanide, and drying is supposed to reduce Cyanide. But the 6/3/25 pair had 2x the fatal threshold level in the Dried sample versus the Fresh, which was well below toxic level. The dried sample somehow had gotten just as wet as the fresh; later a 2nd run of the moisture test registered half as much, but still 3x as wet as dried 2018 samples which I sent for nutritional testing in 2020. ( They started out crisp; I regret double-bagging versus using a plastic lab jar with better seal.)

The commonly understood trend of Cyanide reduction when ensiled loosely held but with one frightening exception: 7/3/25 “Ensiled 90 days” sample had a bit more Cyanide than did the matched Fresh sample, jumping it to just above the fatal threshold. In the same matched set, 30- and 60-day ensiled samples had less than the Fresh sample, with a less-than-measurable amount in the “Ensiled 60 days” sample.

On 1/6/26, he lab kindly re-tested both the 6/3/25 Dried and the 7/3/25 4 hrs wilted ensiled 90 days samples above, that had such unexpectedly high levels. New levels were even slightly higher (new and old figures are included in the above spreadsheet).

I opened an unsent 6/3/25 ensiled then frozen sample, and it seemed properly fermented, despite the small quart container. Was there some way that Cyanide released by leaves got trapped in a non-gaseous form in my sealed containers, and so didn’t dissipate when opened?

What was happening? Scott Radke, Toxicologist and Director at ISU VDL, took generous amounts of time, intermittently for the next three months, consulting his past toxicology mentor, talking to me, and authorizing bits of re-testing at the lab.

Here are some details we pawed over, beyond my confession above about differing packing densities: All 2025 samples were frozen (some previous 2022-’23 ensiled samples were not frozen); 2025 samples were ensiled in containers that were not opened prior to testing (2022-’23 samples were drawn from larger containers into double bags); the 2025 dried sample which got so wet was double-bagged & frozen, but in ULine bags with imperfect zippers. All 2025 samples were packed and the whole inner box went back in the freezer, before wrapping in a plastic bag and additional outer box at time of sending, a day or two later. Then all were sent in that one package by FEDEX overnight service (2022-’23 samples went piecemeal by UPS 2-day or slower ground service).

None of this got us much closer to understanding, except to recommend future studies using more separated packing with additional layers of plastic (that freezer does have a lot of frozen condensation, and perhaps condensation on cold samples once laid out to thaw at the lab might have gotten into the imperfect zipper-seals of that Dried sample?), possibly more real-life large-batch ensiling, and at least more careful weighing for equivalent packing density, and note-taking… if ever someone takes this up where I’ve left off. : )

Scott Radke sent me an article (linked below), about similarly irregular high Cyanide (a.k.a. Prussic Acid) results from drying regrowth of Sorghum. The authors indicate that if leaves are intact versus damaged, they can re-activate & make more HCN, even when dried.

https://enewsletters.k-state.edu/beeftips/2025/09/01/good-news-and-bad-news-on-prussic-acid/

I machine-stripped the 5/21 Fresh sample, & then hand-stripped to remove twigs; 2022-’23 samples were all machine-stripped then sorted similarly. But I used no machine & only hand-stripped the 7/3/25 samples, by running my hand down new growth only (hoping to get the highest Cyanide level in this young growth). I may have also hand-stripped the 6/3/25 dried sample. Perhaps doing that was less damaging? Yet our machine-separated leaves look mostly intact. And I would have thought that drying for many days in a sunny room & then freezing would cause sufficient damage to release all Cyanide potential, in that fatal dried sample.

As I type on January 11th, I await re-testing of Cyanide levels in those 2 worst samples, which Scott Radke has kindly gotten authorized for no additional charge.

Please if you know more about chemistry which may have happened to cause such results, CALL me! & leave Voicemail: (207) 338-3301

Gallic, Ellagic, & 4 non-proteinogenic Amino, Acid Toxins in Maples, Box Elder & Staghorn Sumac

A goat at Locust Grove Woodworks, Unity ME, died a few years ago of bloat from Box Elder, when fed in a stall with limited choices. Leaves of large, vigorous coppiced Box Elder from Diane and Kevin Weisner’s sunny roadside, Hubbard Brook Farm, Hunt Rd. Unity, ME, were eaten without issue by my steer and goats at June 28th, 2024 time of sampling for metabolomics work, but were refused when harvested from the same site in 2025, on May 1st, May 23rd, and June 21st (my palatability ratings were .5, .5 and 0 respectively, on a scale of 0 to 3, with 0=“refused without tasting,” 1=“tasted,” 2=“eventually consumed) and 3=“immediately consumed”).

Huge healthy growth of a pollarded tree in Unity at MOFGA South Orchard harvested on July 20, 2024 was also refused, when fresh and when ensiled. Yet at least 2 farmers, one in Windsor ME and one in NY State, have told me that their animals use significant amounts of Box Elder without issue.

Diane Weisner (Hubbard Brook Farm, Hunt Rd source of my samples) suggests feeding more repeatedly, to develop familiarity, or in case my animals’ rumen microbes need some shift specific to Box Elder. My animals can count on long daily to twice-daily attended free wanders, or fresh Red Maple in winter, so I’m not sure this would work – though my animals have exhibited evidence of a rumen-adjustment process with more palatable White Birch, when felled in late June.

The Kitchen Box Elder (also previously pollarded) in Unity at MOFGA had a 2x+ greater spike of Hypoglycin B than our other 2 Box Elder samples in 2024. I re-pollarded it on June 21, 2025, and dumped it in shade by my driveway, where my animals passed by but (not surprisingly) took no interest.

(Before sampling, I spent most of a day driving and hiking, looking for Box Elders nearer than Unity. The only nearer Box Elder I found is along the downtown Belfast Rail Trail, in a narrow patch of well-disturbed soil between the rocky bay-front and the parking lot of the old potatoe factory. Karl Hallen, my Tech Advisor, sees lots of Box Elder in NY State and has observed them to thrive in toxic places.)

As noted in Westermann (2016), regarding levels of Hypoglycin A in Maple species), toxin levels can vary greatly from tree to tree. Our species with highest spikes of each toxin had broadly ranging levels among (3) same-species samples, mostly* taken within a day of each other. My animals will browse individual trees or shrubs selectively.

* Jack Kertez froze 2 samples of Box Elder from MOFGA, Unity, for me on the right day, while I was sampling in Belfast. When I fetched them, the trip home to my freezer had other stops; the samples thawed and I worried that their condition was too deteriorated, or at least dissimilar to other samples. So I collected 2 fresh Unity re-dos 4 days after the Belfast sampling.

The animals’ discernment is much more affordable than metabolomic analyses (plus the lab did not have the ability to quantify above toxins other than Gallic and Ellagic Acids), but sometimes the animals aren’t present for my forage harvest. Scandinavian farmers of antiquity were said to taste tree leaves themselves, to know when to cut; this pertained to timing for best nutrition and tree carbohydrate stocking (probably not to toxin levels?). Short of that skill (though my NOSE DOES say Box Elder is not tasty when wilted or ensiled), and hoping that your animals are discerning enough to also guide you, I proceed to report comparison of our 3 samples-per-species average measurements (Gallic & Ellagic Acids) and comparative spikes (Hypoglicins and homologues):

Box Elder metabolomic analyses showed spikes of Hypoglycin B (HGB) and of related γ-glutamyl-MCPrG in each of 3 samples to be drastically higher than in our other species, with HGB barely present at all in other species. Box Elder was 2nd highest in HGA (to Sugar Maple, though one Sugar Maple sample was much lower), but lower in average spike-level of HGA homologue Methylenecyclpropylglycine (MCPrG) than all other species tested, with range similar to that of Staghorn Sumac and Norway Maple.

Our spikes of HGB in Box Elder leaves were consistently much higher than spikes of HGA; this was in contrast to findings of El-Khatib et al. (2022), who reported spike-average of HGB in leaves to be 26% of HGA spike-average. They quantified HGA in their leaves at 535 mg/kg DM.

Red Maple leaves are used by my livestock if eaten alternately with other forages over time. In our SARE FNE22-013 3 Streams Farm trial, goats averaged a low 1 lb As Fed ( lbs DM) per goat in the 2 hr offering-periods, with 1.5 lbs As Fed ( lbs DM) maximum average per goat (across 10 goats), and steer Angelo averaged 1/2 lb As Fed ( lbs DM) with 1 lb maximum ( lbs DM); 2 other leaf-silage species usually were offered just after interest in Red Maple slowed, during the 2 hr periods. Animals then finished last leaves plus all the twigs overnight. Winter twigs and bark are an immediately-consumed staple for us, with seemingly less digestive limitation than leaves. When I have brought home Sugar Maple, animal response has been similar (but with slightly less choice twigs and bark).

Red Maple leaf results show Free* Gallic Acid (GA) and Methylenecyclpropylglycine (MCPrG – homologue of Hypoglycin A) to have much higher spike averages than in the other species tested. All species tested showed HGA; Red Maple had the 2nd lowest level (Norway Maple had the lowest).

Both Gallic and Ellagic Acids have been batted around in research as potential additive to cattle feed to reduce methane emissions, or other benefits. Here's the latest quite detailed study I found, with conclusion that "more research is needed," before feeding these acids in vivo to cattle: Manoni et al. 2024: Gallic & Ellagic Acids Differentially Affect Microbial Community Structures...

More surely, Gallic Acid does have positive antioxidant health benefits for humans (Wianowska & Olszowy-Tomczyk 2023: A Concise Profile of Gallic Acid...). I live on Goats' milk, and the goats (and steer) do eat some Red Maple leaves regularly. I did not find anything about whether Gallic Acid makes it into milk (clearly not enough to curdle the milk, thank goodness).

*A discrepancy seemed to exist in the Free and Hydrolyzed (which was supposed to indicate Total GA, including free GA plus GA in more complex molecules such as toxic hydrolyzable Gallotannin) GA figures. In 7 of 12 samples (across species and including all 3 samples of Red Maple), Free GA level was higher than Hydrolyzed. Ellagic acid (EA) figures less strongly had the same issue.

Zhentian Lei explained (1/16/25 email): “ The hydrolyzable data (hydrolyzable gallic acid and hydrolyzable ellagic acid) contain the free data. Because the hydrolysis was performed at high temperatures in strong acid, some free gallic acid could be lost due to degradation. Thus, the free gallic acid is a better indicator of its content in the samples while hydrolyzable ellagic is a better indicator of ellagic content in the samples.”

Sugar Maple had contrastingly low levels of the 2 toxins in Red Maple, while Hydrolyzed Ellagic Acid and Hypoglycin A were much higher on average in Sugar Maple than in ant other species.

It interests me that Hypoglycin A (HGA) showed a much higher spike in our Sugar Maple leaves than in our Box Elder leaves, and (homologue of HGA) Methylenecyclpropylglycine (MCPrG) showed a much higher spike in our Red Maple leaves than in those of Box Elder. I had found these toxins mentioned in literature as present in Box Elder and Sycamore leaves (plus maples in the Netherlands that we do not have: Westermann et al. 2016). On reviewing saved sources of info, I did find two studies confirming HGA in Sugar Maple (Novotná et al. 2023; Fowden & Pratt 1973).

El-Khatib et al. wrote that Hypoglycin B (HGB) and its homologue γ-glutamyl-MCPrG had been found in maple species 50 years before (Fowden & Pratt 1973, mentioned above) but were subsequently overlooked until their 2022 study, and all that time HGA was assumed to be the sole cause of poisoning from both Box Elder and Sycamore. (As mentioned above, we found higher HGA in Sugar Maple leaves than in those of Box Elder).

Norway Maple is a highly edible fodder tree from Europe, with leaves that my cattle and goats consistently devour. The leaves stay bright green when ensiled. Our results confirmed low presence of toxins indicated by other researchers (El-Khatib et al. 2022, Westermann et al. 2016).

Striped Maple bark is stripped from young trees by my goats, before it gets established here; I therefore thought they might like leaves from my blueberry property, but they didn’t like them as well as I expected. Wayne Zeller screened relative level of Condensed Tannin in Striped Maple at “10” (on a 1 to 10 scale; Norway Maple was scored 3.5, and Red & Sugar Maple scored 5); I'm guessing that some of the toxins in other maples are there as well, and I'm sad that due to budgetary limitatiions, we did not include Striped maple in metabolomic analyses.

My palatability ratings for their spring of 2025 responses were 1.5= “tasted and ate a bit,” when offered out on a walk, and 2= “eventually consumed” to a rare 3= “immediately consumed” when small qiantities were given in their yard. On June 1st , 2025 Angelo ate some, then left the rest and went to point to Gray Birch in a sled outside the fence. June 24th was no better. September 6th through leaf-drop we lived on the blueberry parcel, and I never saw Striped Maple selected.

Staghorn Sumac is considered by Susan Littlefield to be a choice forage for her Y Knot Farm sheep; my goats refused senescing leaves but ate a few berries, in October of 2023 (the only time we were near some, that year). In 2025 they accepted some in their yard on May 28th, then we stayed on my blueberry field where it is a young weed, for most of June and then September 6th through December 6th. They hardly ate any leaves of that young sumac, but on the way there on September 6th, they briefly gobbled some leaves of a taller specimen along a shady road. Once leaves fell, they started stripping bark of the young field specimens quite eagerly.

Staghorn Sumac results showed second highest average Free GA level (well behind Red Maple), but higher Hydrolyzed GA average than Red Maple, with one sample twice as high as the highest Red Maple sample. The Staghorn sumac sample with lowest GA figures had HGA spike in range of that in our Box Elder samples.

As above described, my animals have given preliminary indication that as with Red and Sugar Maple, the bark has less or no toxins as compared to leaves, so fresh cutting and feeding in winter may be better use than ensiling summer leaves.

MU Metabolomic Toxin Results on Maple Species & Sumac, Final (pdfs above & below are formatted to print on legal-sized, landscape-oriented paper.) MU Metabolomics Charts & Graphs made by Gentian Lei (edited slightly by Shana)

Antifeedants in Birches: I have in past looked for chemical info explaining my animals intermittent use of Gray Birch with a lot of refusals once stored, and somewhat less limited use of White Birch, to no avail. Yet just now I Brave-searched "Antifeedants in Gray Birch that inhibit browsing by animals" and got this: "plant secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, tannins, and terpenes, are known to contribute to antifeedant properties in birch species. These compounds are often bitter or toxic, reducing palatability and deterring feeding. For example, bark phenolics and volatile terpenes in birch trees have been shown to reduce herbivore feeding behavior." Yet still I found no studies specific to birch, and cannot (at this late date of report submission) chase the references in general antifeedant studies. Please call me if you do so, with palatable morsels of info for me to ruminate on, while I watch my herd devour Gray Birch fresh, next spring or fall: (207) 338-3301.

Yet I included this section, to at least summarize my animals' limited intake amounts of Gray Birch leaf-silage from our SARE FNE22-013 3 Streams Farm trial, and tell you that our quite eager fresh eating of Gray Birch in spring or fall is more predictable and worthwhile than our storage efforts, either ensiled or dried.

White Birch leaves are preferred to Gray Birch when fresh or ensiled, with spring or fall harvest still preferred, and hybrids of the two seem to retain benefits of White Birch (wild hybrids seem to abound on our blueberry land, but as yet least palatable but best soil pioneer Gray Birch dominates).

Yellow Birch leaves are well-received all season whether fresh or ensiled.

If leaf-species mixes are to include Gray Birch, perhaps intake levels during the once-per-day 2-hr offering-periods in our SARE FNE22-013 3 Streams Farm trial can give some guidance; note that once interest waned for these species, I then stopped adding more and started offering other leaf-species (with aim for them to eat leaf-silage to full capacity, during those 2 hrs).

Gray Birch intake levels are offered here above levels of next most intake-limited Red Maple leaf-silage (discussed under Red maple in Maple Toxin section above).

CONDENSED TANNINS (CT) *