Final report for FNE24-085

Project Information

Our question was whether plant nutrient levels can be maintained in acceptable ranges if regular fertilizer additions are made without nutrient solution replacement. To test this, hydroponic systems were used with either regular fertilizer addition or nutrient solution replacement protocols. EC, pH, temperature, and individual macronutrient measurements were taken. We found that yields were similar in both treatments, however additional nitrate, phosphorus, and potassium at strategic times may improve yields further. We found that EC alone was not predictive of individual nutrient concentrations. However, if pH and temperature data are included, more useful models can be instructed. Our findings have informed our farmer trainings which include instruction on fertilizer use in simplified hydroponic systems. We presented our results and have created training videos to enable our staff and other farmers to understand and benefit from our fertilization approach.

Our first objective (Obj. 1) was to determine the concentration of macronutrients over time in nutrient solutions which are, or are not, replaced. We hypothesized that macronutrients decrease in a consistent pattern over time and that measurements of electrical conductivity (E.C.) and total dissolved solids (TDS), which provide an estimate of the total concentration of ions in the solution, can be used to estimate when nutrients should be added.

Our second objective (Obj. 2) was to test the hypothesis that reuse of nutrient solution decreases the inputs of fertilizer and water sufficiently that it justifies decreased yields. To test this hypothesis, we conducted yield trials at Levo farm locations in which nutrient solutions was regularly replaced or not replaced for the duration of a crop.

Our third objective (Obj. 3) was to record the incidence of disease in systems described in objective two. We hypothesized that due to the rapid multiplication and spread of root rot causal agents such as Pythium, recycling of the nutrient solution will not lead to greater risk of disease.

Hunger may be at its worst levels in over a quarter century, with over 20 million people living in food deserts (1). Urban agriculture is one important component of creating access to healthier food choices for many suffering from food insecurity, but obstacles to urban agriculture are substantial.

Significant literature indicates that environment plays a role in dietary behaviors and health outcomes (2). Several challenges are associated with urban agriculture including soil contaminants, water availability, and changes in climate and atmospheric conditions. Utilizing hydroponic farming methods can address these challenges. Hydroponics is the growth of plants in a water-based nutrient solution, without the use of soil. Hydroponics is a sustainable form of agriculture because it does not require arable land and enables the efficient use of resources such as water and fertilizer in a closed loop system. One of the biggest challenges with hydroponics is that it is not very accessible for many due to high start-up costs and complexity of operation. Levo’s simplified deep flow technique (DFT) hydroponic systems overcome the inaccessibility challenge allowing hyper-local placement of growing operations otherwise not practical utilizing traditional agricultural methods.

Levo International was founded to address food insecurity through agricultural innovation. As part of fulfilling this objective, the organization installs urban farms and trains neighborhood residents to operate them. Research suggests that hyper-local proximity to fresh vegetables has an impact on consumption of vegetables. Indications are that increasing fresh vegetable availability within 100 m of a residence correlate to greater vegetable intake (2).

The key to the hyper-local farming strategy is that accessibility must be defined in terms of cost, geography, and operation. Levo utilizes simplified hydroponic methods as the principal driver of participation. By developing and deploying hydroponic systems that are simpler and less expensive to build and operate, we increase accessibility and retain the sustainable benefits of hydroponic production.

It is standard practice in hydroponic production to either regularly replace the nutrient solution or to frequently complete analysis of the ion content of the nutrient solution and make adjustments accordingly (3). This is because plants unevenly consume ions from the nutrient solution over time, leading to imbalances in available nutrients which can have deleterious effects on plant health. Nutrient solution replacement costs a great deal in wasted water and fertilizer and constant ion measurement and adjustment is prohibitively expensive. In a recent research project, we produced both greens and fruiting crops on par with field production without replacing the nutrient solution (4). To accomplish this, we used a lower than standard salt concentration and added nutrient ions slowly over time. In order to fully implement this more sustainable approach and recommend it to growers, we needed to know how yield is affected compared to systems in which the nutrient solution is regularly changed.

1. Morris, Alanna A., et al. "Relation of living in a “food desert” to recurrent hospitalizations in patients with heart failure." The American journal of cardiology 123.2 (2019): 291-296.

2. Bodor, J. Nicholas, et al. "Neighbourhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: the role of small food stores in an urban environment." Public health nutrition 11.4 (2008): 413-420.

3. Resh, Howard M. Hydroponic food production: a definitive guidebook for the advanced home gardener and the commercial hydroponic grower. CRC press, 2022.

4. Vega, Isabella, et al. "Intermittent circulation of simplified deep flow technique hydroponic system increases yield efficiency and allows application of systems without electricity in Haiti." Agriculture & Food Security 12.1 (2023): 18.

Levo International, Inc. has been farming in Connecticut since 2020. We produce a wide range of specialty crops and primarily sell our produce in a Community Supported Agriculture program and in farmstands.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

- - Technical Advisor

Research

The experimental unit for the completed research is the Levo Victory Garden system, described in Vega et al (2023). This system is widely used in Levo’s growing operation. This system is a deep flow technique system which enables nutrient solution circulation in a system in an A-frame layout and uses a standpipe to maintain the level of nutrient solution. Nutrient solution is recycled from a reservoir tank up to the top pipe of the system on an intermittent basis during the day. 27-gallon systems with 20 plants were used for pepper and lettuce production at the Lockwood Farm location with nutrient addition or replacement every three weeks. 55-gallon systems with 72-76 plants were used for pepper and tomato production at the Homestead Farm location with nutrient addition or replacement every two weeks.

Seeds were germinated in 1 inch2 rockwool blocks and after their emergence were fertilized with half-strength fertilizer consisting of 2 g/gallon of Jack’s (J.R. Peters) 5-12-26 NPK fertilizer and 1.25 g/gallon of calcium nitrate. Upon the emergence of initial true leaves, seedlings were transferred to 3 inch2 net pots in trays and perlite was added to stabilize seedlings. Seedlings were watered with half-strength fertilizer until they had a minimum of four true leaves and their roots protruded from the bottom of the net pots marking them as ready for transfer into VG systems. This occurred at approximately three weeks for lettuce and four weeks for bell peppers and tomatoes.

Systems were run with either addition or replacement protocols. Under both protocols, VG systems started with a mixture of water, 4 g/gallon 5-12-26 NPK fertilizer, and 2.5 g/gallon of calcium nitrate. For the addition protocol, an addition of 2 g/gallon 5-12-26 NPK and 1.25 g/gallon calcium nitrate was made. For the replacement protocol, the reservoir tank was emptied and replaced with fresh nutrient solution at 4g/gallon 5-12-26 NPK and 2.5 g/gallon calcium nitrate.

Lettuce plants do not require nutrient additions or replacements for a single growth cycle, which can be as short as three weeks. However, most operations, including our own, will continuously harvest and add in lettuce plants. To replicate this, we carried out a trial in which half of each system was planted with lettuce and the other half was planted a week later. After four weeks of growth each round of lettuce was harvested and replaced, so that the harvests were staggered between two weeks of growth.

Weekly measurement of EC values was completed with a VIVOSUN EC meter. Weekly pH measurement was completed with a VIVOSUN pH meter. Water samples were taken weekly from experimental systems. Nitrate values were measured with a Howard Hanna nutrient photometer or with an API nitrate test kit. Water samples were tested for phosphate, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur via inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy in the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES) Analytical Chemistry laboratory.

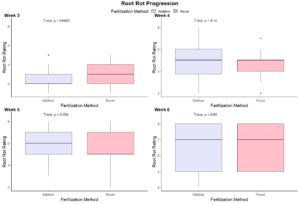

Regular experimental walkthroughs were carried out to scout for signs of wilting diseases. Roots were inspected weekly for signs of root rot. Incidences of root rot were rated on a scale from 1-8 and disease progression was recorded in systems. The experimental technicians wore gloves and cleaned them with 70% isopropyl alcohol or hand sanitizer between systems to prevent transfer of pathogens between systems.

Research was conducted at Levo’s Homestead Avenue Farm and the CAES Lockwood Farm. This was two rather than the initially proposed three locations. This was chosen because of land availability for the large trials. We were able to begin experiments at a new location on Homestead Avenue in 2025 which offered adequate space for the experiments. In the end this improved data collection and observation compared to the initial plan spread across three locations.

Table 1. Linear regression models including EC, water temperature, and pH as factors best predict nutrient concentrations according to multiple R2 values.

|

Nutrient |

Model |

p-value |

Multiple R2 |

|

N |

Concentration ~ EC |

0.2868 |

5.38% |

|

P |

Concentration ~ EC |

0.0002 |

50.21% |

|

K |

Concentration ~ EC |

0.0002 |

48.20% |

|

Ca |

Concentration ~ EC |

0.0003 |

46.75% |

|

Mg |

Concentration ~ EC |

0.0005 |

44.42% |

|

S |

Concentration ~ EC |

0.0006 |

43.33% |

|

N |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp |

0.0437 |

37.22% |

|

P |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp |

0.0002 |

65.86% |

|

K |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp |

0.0002 |

54.66% |

|

Ca |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp |

0.0044 |

52.90% |

|

Mg |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp |

0.0126 |

46.28% |

|

S |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp |

0.0006 |

48.22% |

|

N |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp * pH |

0.4617 |

42.13% |

|

P |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp * pH |

0.0029 |

83.63% |

|

K |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp * pH |

0.0111 |

77.93% |

|

Ca |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp * pH |

0.0074 |

79.83% |

|

Mg |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp * pH |

0.0327 |

71.72% |

|

S |

Concentration ~ EC * water_temp * pH |

0.0165 |

75.87% |

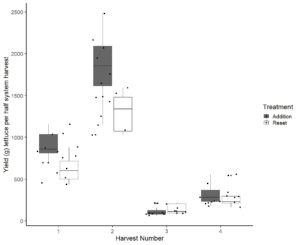

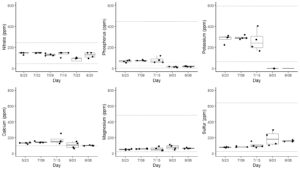

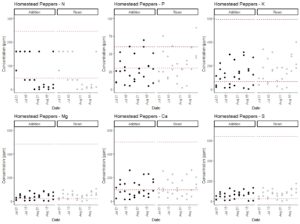

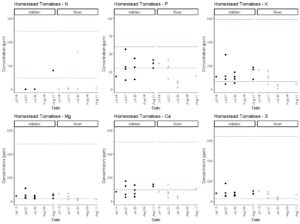

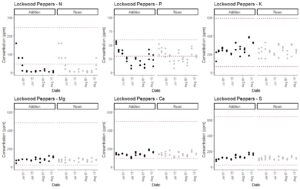

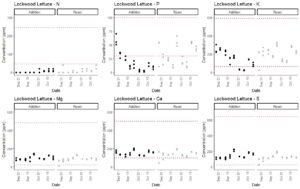

In completing Obj. 1, we measured the concentration of the macronutrients nitrate, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur over time in nutrient solutions that were or were not replaced. We had initially hypothesized that macronutrients decrease in a consistent pattern over time and that measurements of EC and total dissolved solids, which provide an estimate of total concentration of ions in the solution can be used to estimate when nutrients should be added. We therefore conducted linear regression modeling to test relationships between EC and individual nutrient concentrations. Using bell pepper data, we were able to build a model to predict phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur concentrations from our collected data. The best models in terms of R2 values were those that included EC, temperature, and pH as interacting factors (Table 1). Nitrogen model R2 values were low (Table 1), so we recommend the use of nitrate test kits to estimate nitrogen concentration in real time.

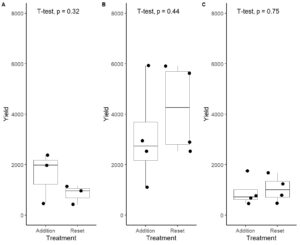

We had expected that yields would be lower in systems using the addition protocol compared to the replacement protocol. This led us to develop our hypothesis in Obj. 2 that reuse of nutrient solution decreases the inputs of fertilizer and water sufficiently that it justifies decreased yields. However, we found that yields were similar and not significantly different in systems using the different protocols (Fig. 1-2). The addition protocol used substantially less fertilizer and did not require dumping of the nutrient solution. As it promotes similar yields this is a clear cost-saving approach for hydroponic farmers.

The 2013 edition of the book Hydroponic Food Production by Howard M. Resh lists the concentrations of macronutrients in published fertilizers. These include a range of recommended concentrations in parts per million (ppm) for calcium (98-500 ppm), magnesium (22-484 ppm), potassium (65-593 ppm), nitrate (47 - 246 ppm), phosphorus (4 - 448 ppm; mostly 30-60 ppm), and sulfur (26 - 640 ppm). Macronutrients were in acceptable ranges during the majority of the experiments for both system types (Fig. 3-7). Nitrate nitrogen and phosphorus levels were the exceptions that regularly dropped below the recommended concentrations, but this was consistent across both fertilization protocols. Potassium levels tended to decrease during the end of the experiments when crops were fruiting. Therefore, we recommend the usage of aquarium nitrate and phosphate test kits to regularly track these nutrient levels. Potassium phosphate and calcium nitrate additions can be used to correct these deficiencies. Potassium and calcium levels were at the low end of the recommended additions and therefore additions of calcium nitrate and potassium phosphate to correct for nitrate and phosphorus deficiencies are unlikely to result in calcium or potassium toxicity. As described above, modeling can be used to time potassium phosphate additions. However, calcium nitrate should be added in response to direct measurement of nitrate concentrations according to a drop test kit. As nitrogen levels were low in most cases, we will increase calcium nitrate applications in our production in the future. This has the potential to substantially increase yields and would not have been detected on the basis of the typical EC-based approach.

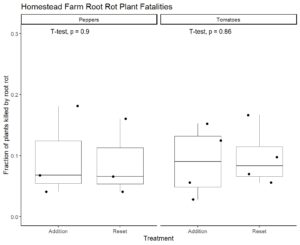

To fulfill Obj. 3, we recorded data on root rot occurrence and severity. There were outbreaks of root rot in both pepper and tomato experiments. This similarly affected both system treatments in terms of plant loss (Figure 8). Based on our observations of disease development, we created a disease rating protocol to enable rapid and reliable assessment of root rot progression (Figure 9). We applied this disease rating protocol to track an outbreak of root rot in the pepper plants grown at Lockwood Farm (Figure 10). We see that disease development occurred at a similar rate in both treatment groups again. Therefore, we conclude that use of the addition protocol does not increase the likelihood or impact of root rot outbreaks.

A combination of EC, pH, and water temperature data can be used to predict the concentration of nutrients in systems using the nutrient addition protocol. A farmer can conduct an initial trial to determine this relationship for their particular systems using these parameters. Affordable (~$20) and rapid (~5 minutes) test kits for nitrate can be used to supplement modeling based on EC, pH, and water temperature for other plant macronutrients. Specific measurement of nutrient concentrations led us to detect shortages of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium that were not clearly reflected by EC values. Additions of calcium nitrate and potassium phosphate during production will likely improve yields. This will require re-calibration of our predictive models due to the adjusted protocol. Yields were not different between systems with nutrient additions and those with nutrient solution replacement. Therefore, use of the nutrient addition protocol can save farmers fertilizer and water input costs while retaining yields. Root rot affected both treatment groups similarly, meaning that use of the addition protocol does not likely increase the risk or severity of root rot for pepper or tomato production.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

We presented our data at the 2025 CAES Plant Science Day. We will present our updated findings at the 2026 CAES Plant Science Day. We taught protocols including the regular nutrient addition protocol to 18 participants in our hydroponic farming training program in collaboration with the Hispanic Health Council in Hartford. As described below, our goal is to use the available data to create a protocol farmers can follow to understand nutrient dynamics without testing. We also determined that affordable aquarium nitrate test kits could be used to replace expensive and relatively slow laboratory nitrate testing to give farmers immediate data about nitrate concentrations to inform fertilizer additions even if modeling based on EC is not reliable for nitrogen. The recommendation of use of an affordable nitrate test kit was published in a recent peer-reviewed article in the open-access journal MethodsX (Tarvin-Imeokparia et al. 2025). We have created two training videos targeted to other hydroponic producers and would-be hydroponic producers that explain how to set up a hydroponic nutrient solution based on our findings in this project.

Journal Publication: Application of multiple parallel mineralization method to grow lettuce, Swiss chard, and peppers in a simplified deep flow technique hydroponic system - ScienceDirect

Training Video 1: https://youtu.be/MstzJexXWFU

Training Video 2: https://youtu.be/xGugIC9zpK0

Learning Outcomes

We provided training in our approach to 18 new farmers via a collaboration with the Hispanic Health Council. They were new to hydroponic agriculture and so gained knowledge in the basics of hydroponics as well as how to use our approach to make regular nutrient additions and minimize water and fertilizer usage.

Project Outcomes

Through this project we discovered that electrical conductivity was not a reliable way to track nutrient levels in our nutrient solution. This research demonstrated that we should increase fertilization rates when crops such as peppers and tomatoes are fruiting to increase phosphorus and potassium levels. We also found that nitrate concentrations should be specifically tracked and that one can do this with affordable nitrate test kits designed for aquariums. These adjustments are large changes in our practice of fertilizing our hydroponic systems. We also expect that our results will influence other hydroponic producers regionally and nationally who currently constantly replace their nutrient solutions to keep a balance. Our data demonstrate that one can use regular small additions of fertilizer to avoid the waste associated with regular replacement of the nutrient solution in hydroponics.

Our study's approach was relatively straightforward as it primarily consisted of us comparing nutrient levels and EC values over time in hydroponic systems which followed the industry standard approach of regular full replacement of the nutrient solution or our innovative approach. This gave us a clear picture of the nutrient levels over time and allowed us to make adjustments. This answered our question of whether EC was able to predict individual nutrient values, and the answer was no. However, for several key macronutrients we were able to construct fairly reliable models using EC along with other environmental parameters that predicted nutrient concentrations. Therefore, our approach can be used to determine the nutrient dynamics in hydroponic systems so that potential deficiencies and errors can be quickly detected.