Progress report for FNE24-102

Project Information

Honey bees experience a colony-level reproduction event, called a swarm, where the colony's original queen leaves the hive along with about half of the bee population. The original colony has queen cells on the verge of hatching, which will become the colony's new queen. These "swarm queens" are statistically larger and more robust than honey bee queens reared by beekeepers using the conventional Doolittle method. Larger queens will lay larger worker bees, which ultimately improves the colony's potential health and honey production.

This study sought to create a method of rearing swarm queens on demand, which could be adopted by commercial and hobby beekeepers alike. The process manipulated colonies to simulate swarming conditions, and offered the queen bees various frame and queen cup configurations to lay in. The honey bee queen was confined in an isolation cage in different sized colonies, as well as allowed roam freely within a small colony.

A honey bee colony could be manipulated into creating usable swarm queens in a suitable manner for hobbyists, but not at the levels a commercial queen breeder would need. The tested configurations were not completely reliable, quite likely due to the colonies not experiencing suitable swarm signals. This might be attributed to the colony's experimental size, a theory that has informed further development for 2026.

Create a new queen-rearing process that induces a queen honey bee to lay eggs directly into beekeeper-supplied queen cups. Test successful methods in real-world situations with volunteer beekeepers. Communicate project results through in-person and virtual talks, as well as trade magazine publications.

Problem

This project tackles the challenge of inducing a queen to lay eggs in beekeeper-provided queen cups. The beekeeper can then use those queen cups for personal use in the apiary, or commercial use in their farm operation. By avoiding many of the factors that lead to lower reproductive queens (McAffey, 2023) (Tarpy, 2023), this will allow for better quality queen production, stronger resulting colonies from those queens, and also encourage local queen rearing. Colony loss due to queen issues was the dominant cause during the summers of 2021 and 2022 for all beekeepers (Aurell et al., 2023), and the second-most common cause of winter colony loss for commercial beekeepers. With annual colony losses ranging from 40-50% (Aurell et al., 2023), better quality queens could potentially have an oversized impact on survivorship, particularly for hobby beekeepers.

In emergency situations, a honeybee colony has no choice but to raise a new queen from available resources (very young larvae) or the colony will perish. Using this impulse to rear queens has a high success rate. This process, called the Doolittle method, has been the standard practice since the 1880s.

Honey bee colonies also make new queens when they prepare to swarm – a colony-level method of reproduction. Anecdotally, beekeepers often comment that swarm queens make the best queens. However, to my knowledge raising queens based on the swarm impulse (where the queen lays an egg in a queen cup) for commercial or breeding purposes has not been seriously pursued.

Swarm-impulse queen rearing is not a straightforward task. If a beekeeper simply places a frame of empty queen cups into a colony the queen will not successfully lay in them. It is far more likely that the worker bees will create worker-sized cells on the beekeeper’s queen frame instead of queens.

It is not known exactly what induces a queen to lay in queen-sized cups as the colony prepares to swarm. The worker caste most likely controls the entire swarm process, starting with the process of making (“drawing out”) natural queen cups. After the queen lays in the cups, and prior to swarming, workers will create large queen cells (cups now occupied by a developing queen) that hang vertically in the hive (all other cells are oriented horizontally).

These queen cups can exist in a non-swarming colony as well, remaining unoccupied by a queen-destined egg or larva. This suggests that even if the queen lays an egg in a natural queen cup, workers may remove those eggs if there is no need to raise a queen. It is also possible that workers in a swarm-ready hive will corral the queen toward queen cups they have prepared for her so that she is induced to lay in them.

In order to have the queen successfully lay eggs in beekeeper-supplied queen cups, the colony must be manipulated to mimic a swarm condition where the workers will allow (or induce) the queen to lay in these cups. By offering the colony manufactured queen cups, the bees will have a template to suggest a need for swarm cells, and the beekeeper will be able to safely remove ripe queen cells. This reduces the risk of damaging the developing queens, and results in queen cells that can be safely transported between colonies or to other beekeepers.

The methodology will be crafted to bring the process of queen rearing within easier reach of all beekeepers, particularly hobbyists and small-scale producers. By removing the highest perceived (and real) barrier of grafting delicate larvae, beekeepers could raise multiple queens by using techniques they already practice in their apiaries; managing colony population, confining the queen to a restricted area of the hive, and conducting frame manipulations.

Solution

This project will test manipulations of honey bee colonies, queen cups, and queen cell frames to identify steps that will successfully convince the colony to create queens in beekeeper-offered queen cups. A successful process will enumerate steps that smaller beekeepers can use to raise queens to improve the health or genetic strain of their colonies. The ideal result will be one that large-scale breeders could adapt for their own operations in a cost-effective manner.

Once a successful method is identified, additional beekeepers will be recruited to test the methodology in their own apiaries. These beekeepers will have at least three years of overwintering success, and apiaries of varying sizes, with a desire to raise queens for personal use or sale. Additional feedback from these real-world trials will be used to further refine any successful technique.

Shelley Stuart has been beekeeping since 2009, and became a Cornell Master Beekeeper in 2017. The apiary currently has 17 full-sized colonies and three nucleus colonies. After several years of farmers' markets and online brewing kit sales, she is turning toward breeding bees on a small scale. She has used the traditional Doolittle method of queen rearing, has traditional queen rearing equipment, and with this grant endeavors to create an approachable method to raise bigger queens through the natural honey bee swarm process. If successful, the swarm queen method of rearing honey bee queens will allow beekeepers of all skill levels and sizes to successfully breed more robust queens for their apiaries, operations, and local environments. An additional focus is to perfect a method that does not require specialized equipment so that a beekeeper can easily use off-the-shelf supplies.

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

Research

Colonies

The experiments used colonies housed in eight frame Langstroth hives (deep/medium) and five frame nuc boxes (deep frames only). Colonies were headed by second year (overwintered) queens with the exception of one nuc that entered the trials in June 2024. That nuc had a first-year, swarm-raised queen.

Bees were kept restricted with regards to space and the population deliberately pushed to overcrowding to help trigger swarm instincts. Abundant pollen and nectar, another known swarm trigger, was available naturally to the colonies during May, so it was unnecessary to supplement colonies with additional nutritional stimulus in the forms of pollen patties and sugar syrup.

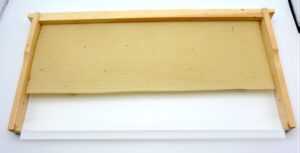

Based on results from 2024 trials, the experimental setup in 2025 focused on using five-frame nuc boxes with the swarm queen frame placed in the center position (position three).

Swarm Queen Frames and Cups

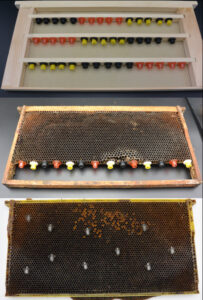

In 2024 bees in the experimental trials were offered swarm queen frames with only queen bars and cups, frames with partial brood comb and partial queen cups, and fully drawn brood frames with queen cups pressed into the face. (Figure 1.)

Each frame contained a variety of queen cups: standard JZBZ cups, 3-D printed cups with a larger diameter than JZBZ, and wax-dipped cups pressed onto a 3-D printed base (to make them easier to use on a queen bar). (Figure 2.)

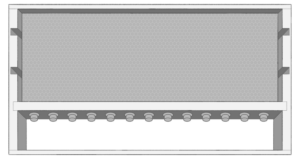

In 2025, the trial focused on only frames with the top 3/4 of comb, and a queen bar placed directly below (figure 3), with only commercial JZBZ cups on the queen cell bar.

If the colony started to build worker comb in the lower 1/3 gap, the worker comb was removed and the queen cups re-exposed to the colony.

Queen Control

In 2024, in both full-sized hives and nucs, queens were confined in a deep frame queen isolation cage and given a swarm queen frame with queen cups. Additionally, in one nuc colony the queen was allowed to freely roam the colony, where frames prepared with queen cups were available for her to lay.

In 2025 queens were allowed to freely roam the nucleus colonies.

Results

Observed limitations of the proposed methods

- With the original single deep method (2024), once the colony reached a swarm level population the colony was packed with thousands of bees.

- Finding the queen in this mass was extremely challenging and/or time consuming.

- Manipulating the queen can be daunting and tricky to accomplish without injury to queen or stings to the beekeeper.

- A similar problem exists when checking a swarm queen frame in an isolation cage. A laying queen with a frame of brood and swarm cells means that the frame may be covered with worker bees feeding the larvae. Pulling the frame out to check the status of the queen cells -- or to remove the queen cells -- risks the queen escaping or getting damaged.

- Frames with queen cups pressed into the side of the frame (figure 1, bottom) proved unusable; the cups added too much width to the frame to fit into the isolation cage, and they would be jostled loose when the frame was added to or removed from neighboring frames.

- In the nucleus (small) colony experiments (2024), the queen isolation cage was prohibitively large and reduced the colony laying area too much.

- A total of 26 fully capped queen cells were produced, with another dozen or more charged queen cells never progressing beyond egg or larvae. Participating beekeepers reported a total of 5 fully capped queen cells, one of which was placed in beekeeper-offered queen cups.

Bee behavior

- Simply placing a swarm queen frame in an isolation cage with a queen does not result in charged queen cells within 48 hours (or any short period of time).

- If left in the isolation cage long enough (approximately three weeks) the queen will lay eggs in queen cups.

- After three weeks, most capped brood in the colony has emerged and the colony is stepping back from a swarm impulse.

- After testing the various frame configurations, the most successful one appears to be frames which had open and capped brood directly above the queen bars (Figure 3). This seemed consistent in my apiary, as well as others’. Experimental frames where the bees built over the queen cups almost always had honey or pollen in the cells above the queen bar, and subsequently became resource frames (pollen/honey) not brood frames.

- When the bees used beekeeper-supplied queen cups (wax, 3D printed, and JZBZ) they did not appear to show a preference for the kind of cup or opening diameter. For all types and sizes (the diameter of the opening), the workers initially restricted the diameter of the opening of the queen cup before an egg was laid in the cell.

- When using a nucleus-sized colony, it was not necessary to add the queen isolation cage for a successful outcome.

- Bees consistently "uncharged" queen cups: they removed eggs and larvae from queen cups for undetermined reasons. This happened multiple times in different colonies over both years and seems to indicate a behavior, rather than an accident.

- To avoid workers uncharging queen cells, a queenless cell starter/finisher (also a nucleus-sized colony) was established as per common queen rearing practices. The cell starter/finisher uses nurse bees to nurture grafted queen larvae to maturity and is a standard, well-tested method. A queen frame with four charged cells on it (three with eggs, one with a newly hatched larvae) was moved to a queenless cell starter colony. Three days later, despite their queenless status, the workers had cleaned out (uncharged) the swarm cells.

- Workers often start queen cups where they want to on the queen bar, ignoring the offered, commercial queen cups.

- They will put swarm cups on the sides of frames (traditionally the location of supersedure cells, commonly seen as emergency queen building, not swarm, cells).

- It appears that they will readily make swarm cells along the bottom edge of comb, if space is available. (Figure 4a, 4b)

Figure 4a: queen cells drawn on free comb. (Photo: Christel Trutmann)

Figure 4b: queen cell from the author's apiary circled. (Click to open an enlarged view in a new window.)

- In both volunteer and home trials, workers would try to draw comb in the bottom third of the swarm queen frame, often repeatedly after such comb was removed by the beekeepers.

- Capped queen cells, measured from the base of the cup to the tip of the cell, ranged from 28.0 mm to 39.1 mm in length (median: 31.8 mm).

Discussion

The intent was to make a swarm queen rearing protocol that is accessible to hobbyists as well as more commercial queen rearers. With the original single deep approach, when the colony is pushed to the swarm impulse locating the queen in the resulting mass of bees took a decent amount of time and could be prohibitive for a newer or inexperienced beekeeper. It was necessary to have additional equipment on hand to move frames from the active box to a "holding" box to more efficiently locate the queen.

Isolating and moving a queen into an isolation cage with a swarm frame already in it presented another challenge. A hobbyist is probably not accustomed to picking up and moving a queen safely with their fingers. A commercial queen catcher can help alleviate this problem for the newer beekeeper.

When utilizing the queen isolation cage, if the queen is accompanied by a large number of worker bees (which happens when the swarm queen frame has open brood) the mass of bees presents a challenge when trying to check the swarm queen frame for queen cells, to keep the queen isolated during the frame removal process, and there is also a risk of queen damage as the beekeeper pulls the swarm queen frame out of (and places it in to) the cage.

After accounting for these challenges, to make a swarm queen the the beekeeper now needs a swarm queen frame, holding box, isolation cage, and queen catcher. This method carries risk to queen damage.

Using the nucleus approach without the isolation cage (2025 trials) proved easy to use, still successful at raising swarm queens, and required a minimal amount of extra equipment; in this case just the swarm queen frame. The risk to the queen in this situation is no greater than risks experienced during normal beekeeping inspections.

The bees were willing to accept all three types of queen cups offered (wax, 3D printed, and commercial JZBZ). However the first thing they consistently manipulated with those cups was the diameter of the opening as seen in figure 5.

The reason for this behavior was not examined during this experiment. Given the consistency, it hints at a mechanical relationship between cell diameter and the fertilization (or not) of the egg being laid. A narrow cell opening could change the queen's physical posture as she positions to lay an egg, and thereby shift her reproductive organs to release sperm from her spermatheca. (See also Patterns, I. B., & Ohtani, T. Behaviors of Adult Queen Honeybees for observational data around this topic.)

In 2024, the largest number of swarm queens generated in a single attempt occurred in the following configuration: on a swarm queen frame that contained only queen cups, with the queen confined to an isolation cage for three weeks (figure 6).

At every observation made during these three weeks, the number of worker bees in the isolation cage remained small. Presumably, since there was no brood on this frame, the worker bees had little reason to enter the isolation cage other than to feed the queen. Therefore any worker influence on queen cell production was very limited, even when the colony was clearly preparing to swarm. The queen may have responded to this lack of workers around her either physically or through pheromonal cues: if she sensed that there were not enough nurse bees to provision larvae, perhaps she stopped laying entirely.

That she did eventually lay in the cups may speak more to her personal biology than to swarm readiness. (After three weeks, capped brood would have emerged in the rest of the colony, making space available to the queen to lay eggs, thus removing a strong swarm pressure trigger.) At that time of year (May) she has started laying hundreds of eggs a day, and suddenly has no place to put an egg. After three weeks the queen may have no longer been able to not lay eggs; her biology may have forced her to use the swarm cells, which attracted workers to the isolation cage. The workers started drawing out the queen cups, but also started to build worker comb for the queen to lay. (Seen most clearly at the bottom of the frame in figure 6 above.)

Having open and capped worker brood near queen cups had a strong influence on the queen laying in those cups. The relationship of brood proximity to successfully charged queen cells repeated with different trials and different swarm queen frame setups. This most clearly showed in a 1/3 brood, 2 queen bar frame from 2024 (Figure 7).

Using a nucleus colony with a free-roaming queen (2025) brought success but also more questions. The small volume of the nucleus box meant that the queen cups were regularly exposed to the workers and the queen. Theoretically the colony could experience a natural, bee-driven, swarm cycle while at the same time provisioning beekeeper-suppled queen cups, which could then be harvested by the beekeeper. This was true in some cases, but unreliably so. The bees would often try to draw out the lower third of the swarm queen frame with worker-sized comb, covering over the queen cups offered to the colony. Even when this space was cleaned to expose queen cups again, the workers would start to build new comb and not swarm cups.

This suggests that the swarm signals were not sufficient to meet the conditions necessary for the workers to nurture swarm queens. Several factors could account for this behavior, in isolation or combination. The colony may not have generated enough bees to achieve a critical mass for swarming; the space allowed did not allow the bees to build enough resources to signal an optimal swarm environment; the genetics of the colony may have disinclined them to swarm.

The incidents of workers cleaning out previously charged queen cells may be connected to swarm signaling as well; if the bees were responding to decreased swarm pressure, they then cleared out the charged queen cells. It also cannot be ruled out that the inspection process influenced this uncharging behavior for some reason.

As mentioned, in an attempt to circumvent this uncharging behavior a swarm queen frame with four charged cells was moved into a queenless colony, only to have that queenless colony remove all of the eggs and larvae in the queen cups. With the cautionary note that this is a single observation, it raised more questions about the swarm preparation event. Did the swarm queen frame bring with it chemical cues that conveyed “get ready to swarm” to the queenless colony? Did the queenless bees interpret cues to mean “the queen is about to take off” and destroy the swarm cells to stop this process so they didn’t lose a queen that they didn’t have? Did the swarm queen frame, and any bees on it, transfer enough queen pheromone with the equipment that the queenless colony was fooled into thinking they were queenright, and no longer needed to build a queen? Will a queenless cell starter consistently destroy swarm cells? If the swarm cells are close to capping will the workers accept them? Was this a fluke (or beekeeper error)?

Finally, based on both 2024 and 2025 observations, offering commercial swarm cups to the bees on a swarm queen frame will produce queens in those cups only some of the time. The workers would also successfully bring swarm queen cells to maturity by creating them at the bottom of drawn comb (figures 4a and 4b). This behavior coincides with the behavior noted in figure 7 where the bees nurtured queens in commercial cups directly beneath capped brood.

Queens would lay eggs in swarm cups when isolated with a swarm queen frame, but neither quickly nor efficiently. By offering queen cups in a nucleus-sized colony, the bees were willing to make swarm cells out of beekeeper-supplied queen cups but not reliably. They would also start swarm cells and then undo that – as though changing their minds about swarming at all. More frequently the colony would draw comb over the cups in the empty space on the queen frames. These behaviors happened in both the main experiment apiary as well as with volunteer participants in two separate locations.

Over the two summers, 26 swarm queen cells reached the fully capped stage, with another dozen or more charged queen cells never progressing beyond egg or larvae. A queen cell length of 25 - 38mm is desired from commercial grafting and the median length of the queen cells indicated that the swarm queens generated would be acceptable in terms of potential adult size. Research participants generated five queen cells in 2025. While a hobbyist may afford this kind of relaxed queen rearing timeframe, a commercial beekeeper needs queens at a more reliable and immediate pace.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

Two feature articles have been accepted by the American Bee Journal for the 2026 season (likely March and April to time with queen rearing season, but as yet unconfirmed by the editor). A lecture is planned for the Finger Lakes Beekeepers Club in the spring. 2025 and 2026 spring updates were posted at HoneyappleHill.com/sare-grant. Information was also shared and encourage to try at the online forum Beesource.com, which. has 61,000 members. I cannot measure actual readership of the queen rearing project, but the information remains publicly available.

Learning Outcomes

Experimental design for 2026

Based on the experimental results from both years, I will work on another iteration in the spring of 2026. I will use a single, eight-frame deep brood box to allow the bee population to increase more than the five-frame nuc allowed. The queen will once again be given full range of the colony, eliminating the need to find and isolate her.

I will remove the queen cell bar and manufactured queen cups from the swarm queen frame and allow the bees to build comb freely along the bottom (figure 8). Based on observations made during the 2026 season, I will offer up to 6 swarm queen frames in the colony, allowing the bees the opportunity to fill the bottom of the frames with freely-drawn comb and swarm queen cells.

With the larger space and unrestricted colony growth, I expect that once the queen cells are charged, they stay charged as the swarm pressure continues to rise for the colony's bees. Once the swarm cells establish at the base of that comb, I will then move that frame or frames to a queenless colony, or cut out the queen cell from the surrounding comb to move elsewhere. Since I am not offering commercial-style queen cups, I will also document recommendations about safely handling, moving, and installing these natural queen cups.

Replacing the swarm queen frames with empty comb is likely to reduce swarming pressure and hopefully allow me to generate another batch of swarm queens from the same colony. (Observations about moving a swarm queen frame into a queenless starter colony will be made if the opportunity arises.)

A final added benefit for the above modification is that it requires no extra equipment for the potential swarm queen breeder, just a modification of already-existing frames that they currently use in their day-to-day beekeeping operations.

Implications for hobby and commercial queen rearing

The viability of using swarm queen rearing as a direct commercial queen rearing process may not be reasonable. Commercial queen rearers need hundreds of queens available on a known timetable. My research has not convinced me this is possible when trying to work with the natural cycle and impulses of the honey bee.

Indirectly, a commercial breeder may benefit by using the F1 generation of bees originating from the swarm queen. Research has shown that larger queens will create larger workers; by using the larger daughter worker larvae in their commercial grafting, commercial breeders may find their grafted queens are also larger. This could allow queen breeders to "reset" the size of their breeding stock while maintaining a commercial-level production volume. This "reset" could happen with one generation of swarm queen, or a beekeeper could allow a swarm queen to raise additional swarm queens before selecting graft stock. Theoretically the second generation swarm queen will be larger on average than the first generation swarm queen, which is herself larger on average than a graft-raised queen. Either way, once the swarm queen starts laying, the queen breeder can then move to mass-production methods with the larvae she generates.

Hobbyists generally need fewer queens for their operations so this method still has the potential for benefitting that cohort of beekeeper. Not only does it omit the delicate, commercial-based grafting process, it allows the hobbyist to improve their own bees, embark on a local breeding program for their own purposes (for example, creating larger mite-resistant bees), and to improve the quality of bees in their local areas through queen swaps frequently found in bee club activities. It requires few (potentially zero) extra resources, and no extra skills beyond solid beekeeping techniques of swarm management and frame manipulation.

Swarm behavior in honey bees

One of the questions I originally identified was "How do eggs appear in swarm cups?" The uncharging events I documented best support the theory that the queen lays eggs in any empty cell she wanders across, and the workers decide what to do with them. (This may happen in our own hives all the time, but our inspection timetables don’t allow us to witness it firsthand.) If the queen laid in the queen cups when swarming was inevitable, the workers should nurture any charged cup to maturity rather than eliminate them. Similarly, if workers were preparing for a swarm and corralled the queen to lay in the cups, those eggs would reach maturity. This may mean that the “practice” queen cups we see on standard frames are not practice at all, but preparation instead. The queen can lay in them so that if the colony needs to swarm it’s ready. If not, the workers clean out the queen cup and put their efforts into rearing worker brood.

New questions arose when I moved my queen frame to the cell starter/finisher. A queenless cell starter should be primed to accept a queen cell in the making, yet the bees cleaned out the primed cups. Did this queen frame bring with it pheromonal cues that conveyed “get ready to swarm” to the queenless colony? Did the queenless bees interpret such cues to mean “the queen is about to take off” and destroy the swarm cells to stop this process so they didn’t lose a queen that they didn’t have? Was this a fluke (or beekeeper error)? Will a queenless cell starter consistently destroy swarm cells? If the swarm cells are close to capping will the workers accept them? Further trials in 2026 should expand upon this initial observation.

Project Outcomes

Using the information gained in 2024 and 2025 I am very optimistic that the changes I plan to make for 2026 will have success for a small-scale honey bee queen production system. Should this prove accurate, I foresee not only livestock sales with quality honey bee queens, but an easy path to breeding a substock of bees with desirable traits. This will benefit HoneyApple Hill's business practice directly. Putting this kind of queen generation into the hands of hobbyists, who frequently strive toward varroa mite-resistant stock, gentle stock, or locally-bred bees, could help transform the quality of honey bees on other local or regional levels.

I did not anticipate an easy solution to my original question, expecting that honey bees would exhibit behavior that would fall outside of our current observed (and expected) swarm behaviors. I was not disappointed. By approaching queen rearing from the swarm queen direction, the bees displayed unanticipated behaviors like the "uncharging" events. Other unexpected findings:

- The proximity of brood to queen cells seems to play an important role in swarm queen production

- A stronger argument for when queens lay eggs in cups (whenever they encounter them)

- It is challenging to get a colony to swarm if it is housed a nucleus-sized cavity

- That workers made a "collar" on manufactured cups, reducing their opening diameter

- Swarm queen production likely is governed by worker bees. They decide where to make the swarm cups, when to allow the eggs laid there to mature, and when to remove them.

As noted in the discussion, in 2026 I will take the lessons learned from the previous two seasons and try to reliably breed swarm queens in a single deep 8-frame colony, allowing the queen to freely roam the entire colony, and modify frames slightly so that the bees create swarm cups at the base of the comb. I plan to cut out these natural swarm cells and use them in my apiary business practices. Once I know the results of this change, I will then be able to make recommendations to other beekeepers seeking the same goal -- multiple large queens made from their own stock, using only equipment on hand and not specialized queen breeding tools.