Final report for FS18-311

Project Information

In our region of Kentucky, many growers have been seeking alternatives for growing tobacco. Incorporating trees into agricultural systems on land previously used to grow tobacco is a viable alternative. Agroforestry has the potential to increase farm profitability and provide environmental benefits. However, farmers need income while fruit and nut trees become established. Growing a crop between trees, called alley cropping, can provide early cash flow. Raising livestock is another option to generate early returns, and has the added benefits of improving soil fertility and helping to control pests.

Many producers are returning to pasturing birds to improve animal welfare, meat quality and environmental outcomes. However, even in pasture-based systems, most of the feed is purchased off-farm with pasture mainly providing bioactive compounds, vitamins, and limited amounts of protein. Producing grain for feed is by far the biggest factor when considering the environmental impacts of poultry production. Offsetting even a portion of the feed grown off-site should reduce negative impacts and benefit a farmer's bottom line, as feed accounts for up to 65 percent of the cost of poultry production.

Before commercial feed was widely available, farmers recognized the need for a balanced diet including a variety of grains and green forage. They planted crops such as barley, oats and wheat for poultry to graze while it was young and tender. Farmers have long recognized the nutritional wisdom of chickens -- the ability to select a balanced diet when given a choice of ingredients. Free choice feeding of whole grains alongside supplemental protein and mineral sources has the potential to lower feed cost without sacrificing performance. Whole grain feeding also helps prevent coccidiosis, a widespread disease that is usually managed by the prophylactic addition of medications to poultry rations.

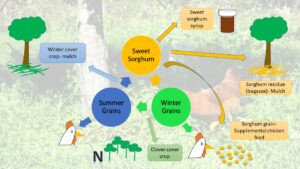

We propose to evaluate an agroforestry system that incorporates sweet sorghum, pasture broilers that self-harvest their feed, and young fruit trees.

After the sorghum is harvested, a mix of winter crops (wheat, barley, triticale, and field peas) will be planted in the fall as feed for the broilers the following summer.

In a separate treatment, a mix of summer feed crops (sunflower, buckwheat, and millet) will also be evaluated as a source of self-harvested feed.

After these crops are harvested, a cover crop of cereal rye will be grown to capture nutrients and provide further mulch for the fruit trees. The sorghum and grains will be grown in the alleys between the rows of apples, which will be used for cider.

Cooperators

Research

Plot Design:

Each year, we managed three different treatments as follows:

Treatment 1: Sweet sorghum, with a winter grain cover crop mix planted after the sorghum in the fall

Treatment 2: Summer cover crop grain mix (grazed by poultry), with a rye cover crop planted in the fall

Treatment 3: Broilers rotated on permanent pasture, moved daily

Treatment 1: (Previously sorghum), winter grain cover crop that is grazed by poultry

Treatment 2: (Previously summer cover crop, then rye), rye cut for tree mulch, then sweet sorghum

Treatment 3: Broilers rotated on permanent pasture, moved daily

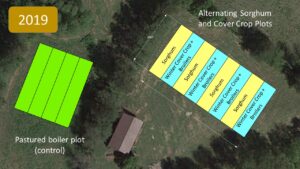

Treatments 1 and 2 each consisted of 4 replicated, alternating plots that were 100' x 25', for a total of 8 plots and a combined area of about 20,000 square feet (roughly 0.5 acre).

Field Preparation:

Soil tests were taken before the study began and after the study was concluded in order to measure changes in soil quality.

On 4/21/2018, the treatment area for the cover crops and sorghum was moldboard plowed to terminate the existing sod, then three passes were made with a disc harrow on 4/28/2018 and 4/29/2018. A fourth pass was made on 5/14/2018.

Sorghum transplants:

A small float bed of the kind traditionally used in tobacco production was constructed using lumber and builders plastic. An organic potting mix was made by sifting and mixing in a wheelbarrow 1 bale peat moss (3.8 cubic feet), 16 quarts of perlite, 1 cup of agricultural lime and 1 cup of organic blood meal. Water was added and mixed in to aid in wicking. After letting the potting mix settle overnight, Styrofoam tobacco trays (288 cell) were filled and 3-4 untreated sorghum seed (variety 'Dale') were planted in each cell on 5/9/2018.

The trays were then immediately floated on water in the float bed and covered with row cover at night. Clear plastic was put over the trays if it rained to keep the seeds from being splashed out of the cells, but we were careful not to overheat the seedlings by leaving them closed up during sunny weather. The trays were left in the float bed for approximately two to three weeks. The process was repeated in 2019, seeding trays on 5/25/2019.

Summer cover crop:

Organic seed was used for all cover crop mixes. The summer cover crop mix consisted of sunflowers ('Peredovic'), Proso millet, and buckwheat. Based on the dates to maturity, we decided to plant the sunflowers about a month ahead of the millet and buckwheat so that they would all mature at the same time so that they would all be available to the broilers in the same harvest window.

Sunflowers were planted with a seeder on a wheel hoe (Hoss) on 5/14/2018 in rows 36" apart with approximately 4" between seeds. The sunflowers ended up being too close together, so they were thinned with a scuffle hoe attachment on a wheel hoe on 6/5/2018. All plots were cultivated with a tiller on a walk-behind tractor (BCS) on 6/9/2018, then millet and buckwheat were broadcast using an Earthway EV-N-Spread broadcast seeder on 6/10/2018. Excessive rains led to a poor stand, so buckwheat and millet were replanted on 6/20/19.

Planting sorghum:

In 2018, half of the sorghum was direct seeded and half was transplanted to compare the differences in labor, harvest date, and yield. Direct seeding was done with a planter on a wheel hoe (Hoss) with a modified custom seed plate. Density was approximately 3-4" apart in rows 36" apart. Sorghum was transplanted from the float trays on 5/25/2018 by hand, having first used a wheel hoe with a shank attachment to dig a furrow. Spacing was approximately 6" to 8" apart in rows 36" apart. Because no rain was in the forecast, sorghum was watered in with a hose by hand. The plots were cultivated between the sorghum on 6/9/2018 with a BCS walk-behind tractor with a tiller attachment. In 2019, the field was prepped with a BCS walk-behind tractor with a tiller after rye had been cut and raked into the tree rows. In 2019, no direct seeding was done due to poor stand development in the previous year. Transplanting was done both by hand as in the previous year and by tractor with a tobacco transplanter to compare systems.

Sorghum harvest:

In 2018, one plot (25' x 100') of the sorghum was harvested by cutting it with a cutter bar mower on a walk-behind tractor on 9/3/2018. It was left to cure in the field for 4 days. It was then loaded into a trailer for storage in the barn to avoid being rained on until it was pressed on 9/11/2018. A firebox was constructed out of cinder blocks to fit the pan rented from another sorghum producer.

The leaves were not stripped before pressing, but seed heads were removed with a machete and laid out on a tarp to dry before storing for poultry feed. The processing equipment was borrowed from Kentucky State University and is trailer-mounted with a horizontal, hydraulically-driven press. Seasoned oak was used as fuel. A second harvest and cooking was done on 9/13/2018, but labor was limited on that day, so leaves were not stripped and it was pressed green. Seed heads were still removed before pressing. A syrup/honey refractometer was used to avoid overcooking the syrup. It was bottled into pint and quart jars. For the 2019 harvest, the harvesting window did not allow field curing, so all cane was cut and stripped by hand before pressing. The final batch was timed so that it occurred on the SARE field day, with roughly 30 people participating in demonstrations of cutting, stripping, pressing, cooking, and bottling sorghum.

Poultry management:

Sixty chicks per batch, with one batch each year, were ordered from Moyer Hatcheries. We used Royal Red due to their advertised improved foraging capability and hardiness. All males were selected both years to control for variability.

Chicks were raised for the first three weeks by partnering farmers who have experience brooding chicks. In 2018, the chicks arrived on 8/8/2018 and were raised in the brooder until 9/1/2018. Two chicks out of sixty were lost in the brooder. At approximately 3 weeks of age, the broilers were transported in poultry cages and put into separate pens on either the cover crop or the pasture treatments. In 2019, the chicks arrived on 5/16/2019 and were raised in the brooder until 6/11/2019, with five losses in the brooder.

The broilers were moved daily for both the cover crop treatments and the pasture treatment. The pens were made of a wooden base with a cattle panel forming a rounded Quonset-style structure that was covered with a tarp. Water and organic broiler feed were available at all times. Electric poultry netting (from Premier1) was used around the portable pens to keep predators out. No birds were lost to predators either of the years.

For the broilers on the cover crop plots, the plots were mowed ahead of moving them. In the summer cover crop mix of 2018, this was done with a bush hog attachment on a walk-behind tractor due to the majority of the seed heads already being predated by birds. In 2019, the winter cover crop mix was cut with a scythe by hand to leave the seed heads intact for the poultry to self-harvest.

For processing, the broilers were loaded into poultry cages in the evening and driven to the processor for slaughter the following morning. Feed was withheld the day before slaughter. All birds were processed into whole, frozen carcasses. Dressed weight was recorded for each bird.

Winter and spring cover crops:

On 10/30/18 after the sorghum was harvested, the plots were tilled with a walk-behind tractor and a mix of winter wheat, winter barley, triticale, and Austrian winter peas was broadcast with and Earthway EV-N-Spread seeder. For simplicity, one bag of each was mixed together and incoulant was sprinkled on for the peas. Rate was approximately 3x the normal seeding rate for these crops in order to provide a good cover, about 400lb per acre.

The plots that had the summer cover crop with the poultry were also tilled and cereal rye was broadcast on 10/31/18 at a rate of approximately 6 bushels per acre (about 300lb).

A spring cover crop of oats and peas was planted in late March 2019 on two of the plots that previously had sorghum. This was a change made in order to spread out availability of feed for the broilers, since the oats and peas would mature slightly later than the winter cover crops.

Orchard planting and management:

In the spring of 2019, 20 pear trees and 25 apple trees were planted between the plots at a spacing of 25' apart in rows 25' apart (5 trees per row). Cultivars were chosen based on disease resistance and suitability for both fresh eating and pressing into cider. After planting, the sorghum residue left over from the previous fall (called "bagasse") was mulched around the trees in a circle approximately 3-4' in diameter. A 5' tree shelter (TreePro) with a stake was installed immediately to prevent deer and rabbit damage.

When the rye was mature on May 25th, it was cut with a sickle bar mower on a walk-behind tractor, then raked into the tree rows with a 60" Molon hay rake, also for a walk-behind tractor. This equipment was used because it fit easily between the tree rows and because it was available. Some hand raking was done to complete the job.

Soil test results:

Given that the study was only two years long and only a single test (both before and after) for each treatment was taken, soil test results should be interpreted with caution. However, there were some clear trends.

Organic matter:

- In pastured plots, organic matter increased from 1.91% to 2.83%.

- In cover crop/sorghum plots, organic matter increased from 1.67% to 2.12%

pH

- In pastured plots, pH increased from 5.2 to 5.4

- In sorghum, pH decreased from 5.5 to 5.2

Nutrients:

- Nutrients measured included: phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, calcium, sulfur, boron, zinc, manganese, iron, and copper.

- For almost all nutrients, levels increased on both pastured and cover crop/sorghum plots over the two years of the trial.

Cover crops:

The summer cover crop had several challenges. Although the sunflowers established extremely well, they shaded out the buckwheat and millet so that there was virtually none by the time the broilers were ready to be put into the plots. Timing was another issue. The sunflowers were mature several weeks ahead of the supposed days to maturity for this variety, and nearly all of the sunflower seeds were predated by wild birds before the broilers could utilize it. However, the sunflowers produced a lot of biomass and multiple wildlife benefits were noticed (pollinators, doves, quail).

Sorghum:

The sorghum was successful, though it was a lot of work. Cutting the sorghum and letting it dry for 4-5 days in the field made for less work because we didn't have to strip the leaves, and the syrup was of good quality. The second batch that was cut and pressed green with the leaves on did not come out as well. The syrup was much darker and retained a stronger flavor. Stripping the leaves and pressing the cane green in 2019 resulted in excellent quality syrup, but took considerably more labor. Producers deciding on which method to use will need to consider available labor, weather, and availability of equipment. Adjusting for scale, we yielded an average of about 100 gallons of syrup per acre over the course of the study.

In these two years (2018-2019) of very rainy, wet weather in Kentucky, the transplant method worked best for establishing a strong stand vs. direct seeding. However, it adds considerable equipment and labor costs to the planting process. Using the tobacco setting equipment on a tractor was a viable option, but with the shallow tillage we did with the walk-behind, it took some hand labor to go behind the tractor and ensure plugs were fully covered.

Since we were able to borrow a press and pan, we avoided the upfront overhead costs of these expensive pieces of equipment, but the logistics of having to coordinate with other farmers who also needed the equipment during a short harvest window meant that we were only able to harvest about half our sorghum crop each year of the study, after already sinking the planting costs for the half that was left unharvested.

Poultry:

The Royal Red broilers did very well in the field, showing good foraging behavior and survival once out of the brooder. Several chicks were lost in the brooders both years, but since we partnered with two different farmers to raise the chicks, it is unknown what factors could have played a role here. There was only one mortality in the field pens over the two year study.

The feed conversion rate was as follows, based on feed consumed vs. lb of finished weight as whole, packaged broiler:

- 2018: (after cover crop with little seed and also on pasture): 3.77lb of feed per lb of chicken

- 2019: (gleaning cut winter grains): 4.62lb of feed per lb of chicken

Cost of feed:

- $0.46/lb ($23.00/50lb bag)

Breakeven (including labor at $10/hour):

- Variable: $4.52/lb

- All costs: $5.96/lb

Losses:

- 2018: 60 chicks ordered, 62 arrived, two lost in the brooder, one adult died of unknown causes in the field= 59 packaged carcasses (1.7% loss)

- 2019: 60 chicks ordered, 60 arrived, five lost in brooder, none lost in field= 55 packaged carcasses (8.3% loss)

Pens: The hoop-style pens did a good job of dissipating heat and providing shade for the poultry. However, the smaller wheel design made moving them difficult on the bumpy terrain. During a storm, one of the pens that had been left in the field blew over, but thankfully the poultry were not in it at the time. After this, we hung the feeders off the front of the pens to weigh them down, while the water barrel seemed to hold the back down adequately. The typical blue tarp we used only lasted one season, and started to fray and leave plastic pieces in the field. Perhaps a different pen design would make this system more convenient and less wasteful.

Winter cover crop: The chickens did appear to graze grain readily, but no reduction in feed use was recorded. Cutting the cover crop with a scythe before moving the pen took an extra 15 minutes or so per day.

Video: Broilers foraging oat cover crop

Pasture: The poultry on grass pasture seemed to have the best feed conversion ratio of all the plots, which was unexpected.

Sorghum grain: The poultry enjoyed pecking at the sorghum grain, but the amount harvested and fed did not seem to make a difference in how much commercial feed the broilers ate.

Timing was a big challenge, especially since we were trying to match cover crop maturity with the growth cycle of poultry. Many factors including weather, soil moisture levels, and chick availability have to be aligned before the cover crops are even at a mature state at a time when the broilers are old enough to forage for them.

We suspect that using cover crops as a feed source in a flexible egg-layer operation would be less challenging, because the layers would be available when the cover crop was at optimal maturity. Mature hens may also have better skills at foraging the grain from the cover crop than young broilers. Another strategy for utilizing cover crops as feed might have been to limit the amount of commercial feed available so that the birds are encouraged to forage more.

Orchard:

Using the cover crop and sorghum residue for mulching trees seemed to work well. The labor and equipment needs for doing this are reasonable, and getting enough residue for a thick mulch was not a problem with 25' wide rows. Although the sorghum bagasse and rye mulch did a good job of holding in moisture and controlling weeds, the trees had to be watered a couple of times during a 6 week drought/heat spell in late August and September 2019. One unknown factor is whether or not voles and other rodents will find the mulch a suitable habitat over the winter and pose a risk for girdling for the young trees. The plastic tree tubes may help prevent some of this, but previous experience has shown that if they can dig under the edge of the tube, they find the interior of the tube to be a cozy environment. Thus, we are putting a 6" section of hardware cloth below each tube on about half the tubes this winter to evaluate whether it makes the tubes more drafty and less suitable a habitat.

Discussion:

Pastured poultry can be a good way to increase soil fertility quickly as well as provide a shelf-stable product. Integrating cover crops into the poultry operation likely contributed to improved soil health, while also providing useful pollinator and wildlife habitat. However, it did not seem to affect the feed use efficiency of the broilers and therefore is not a viable strategy for reducing feed costs.

The economics of organic pastured broilers depends heavily on the cost of feed and efficiency of labor, and we found that to break even at our scale, we would have needed to charge roughly $6/lb for whole birds. This is above what our local, rural farmers markets would likely be able to bear. Economies of scale would bring this number down, but then wholesale markets would have to be found and the production land base would need to be increased, which is difficult in this region where flat ground suitable for movable pens is at a premium on most small farms.

Sweet sorghum was successfully grown between the rows of trees both years and was readily managed with organic practices and small-scale equipment. It provided a valuable mulch that successfully suppressed weeds in our orchard. The shelf-stable product can be marketed at the convenience of the farmer and seems to have a steady, though modest, demand in our area of Kentucky. Challenges include availability of labor, variability of weather, and access to a press and pan for processing.

We were able to successfully establish a small orchard using the residue from the sorghum and cover crops as organic weed control. Additional benefits of the mulch were improved moisture retention and likely improved soil quality as the mulch breaks down. It is unknown how the mulch will affect rodent activity and any subsequent tree damage, but we are happy with the results of the mulch system so far.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Field day/on-farm demonstration:

On September 25th, 2019 we held a field day to showcase the project. We had approximately 30 participants. Ag professionals included staff from Kentucky State University.

As part of the field day, we had demonstrations of processing sorghum, including cutting, stripping, pressing, and cooking. Participants got a handout/factsheet and we had a discussion about the results of the research, including benefits and challenges of the different enterprises. They had a chance to try out the various tasks involved in processing sorghum, and we all enjoyed some of the finished sorghum on biscuits catered by a local baker. There were lots of good questions and interest by the participants.

Presentations:

The results of the first year of the study were presented to approximately 200 farmers in December of 2018 at the Perennial Farm Gathering in Madison, Wisconsin. A follow-up presentation was prepared for the 2019 Perennial Farm Gathering in December of 2019 in Dubuque, Iowa but due to time constraints I was not able to present. However, I was able to have one-on-one conversations with several attendees about the project.

Consultations:

In my work as a small farm consultant, I've been able to share the experiences gained as part of the project with at least 3 small sorghum producers, with recommendations given to additional farmers who are interested in getting into sorghum.

Webinar:

I was able to integrate some of the lessons learned and photos of the project into a webinar I presented for the Savanna Institute in January of 2020 on planning and site evaluation for agroforestry. The presentation was live so that attendees could ask questions and it will be posted to YouTube for public access.

Learning Outcomes

Using cover crops for organic orchard establishment

Cover cropping in pastured poultry systems

Small-scale sorghum production

Project Outcomes

I hope that this project has given farmers in my area a few more tools to make small farming viable both economically and ecologically. The practices that were part of this project led to increased soil health and fertility, which is the primary measure of whether or not an agricultural technique is sustainable in the long run. Given the perennial nature of the orchard in the long-term, we can expect this to continue into the future. The cover crops in the project led to increased pollinator and native bird habitat. The overall organic management of the system meant that no toxic pesticides were used at any time, protecting both the environment and people involved while supporting the organic grain producers who provided the poultry feed.

On the economic side, valuable data was generated that can give producers an idea of what to expect when considering entering into a new enterprise like this. This includes both positive economic outcomes as well as challenges faced during the project. Additionally, my family was able to make connections and build a customer base with consumers and community members through the sale of organic pastured poultry and sweet sorghum syrup.

Finally, this project brought together many farmers and non-farmers in my community who were able to participate in a variety of ways. Farmers partnered in raising the broiler chicks, planting trees, and the entire process of growing sorghum from planting seeds in plug trays to the final cooking of the syrup. Many people especially found the sorghum aspect appealing because it spoke to an agricultural tradition that brought communities together in the fall for sorghum cooking.