Final report for FS23-358

Project Information

Our proposed solution to the problem of “unsustainable rotational paddock fencing”, is the research of effective species of plants for the establishment of: bio-diverse poly-culture lay hedges, or, tightly planted, permanently weaved perennial vegetation. Lay hedges were used for centuries in Europe and are in some areas still being maintained today. Although there was a period where, due to the popularization of barbed wire and modernization itself as a trend, farmers in Europe have destroyed vast amounts of hedgerows, however there is a movement today to restore and protect these hedge rows.

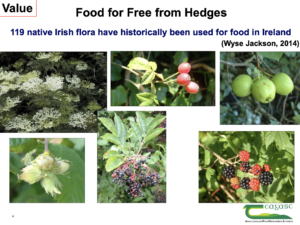

We also note how lay hedges can provide a source of fuel wood, and also fuel for biochar creation or chipping for on farm sourced mulching.

The lay hedges can also provide a crop such as berries, medicinal crops, flowers, and the like, which can further support small to large farming operations and even work in urban applications.

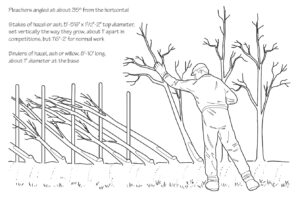

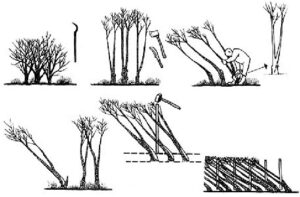

The main thrust of the solution we are proposing is that lay hedges can replace factory produced fencing. After some years of time the layhedges are "pleached" or cut vertically in a long cut that allows the plant to grow in a diagonal fashion closer to parallel with the ground. The plants respond well to this and callous and send vertical shoots which create the framework of the fence. At the top rail of the hedge 5-6' up, willow whips or hazelnut bush cuttings are used to braid and twine the hedge together. The maintenance of this hedge is only needed to be done in a portion of the fence each year, thus over a handful of years the entire lay hedge is continually maintained. The work involved with maintaining a lay hedge in the end will be less than factory produced fencing, and also the input costs will be less overtime, the break out rates will be less and the benefits will be numerable when compared with conventional plastic/wood/steel style fencing.

If we can in fact identify the most effective species of perennials for use in this endeavor in our region, we can then share in our outreach what is working the best and what handles our bulk approach to establishing these lay hedges the best. We believe that by working with the US forestry service and other small nurseries we can acquire the necessary research material but also by utilizing plant material from on farm, or in surrounding marginal areas, such a road sides and ditches where these organisms are typically cut away, we can very cheaply and effectively establish these lay hedges on a budget.

A couple good documents for both managing lay hedges, and the benefits of hedgerows for biodiversity and multitude of other reasons. Really there's almost no reason for every farm not to implement lay hedgerows as soon as possible!

The simplest method to apply this is, given that there might be enough leeway outside ones already established paddocks, one can simply subsoil 2-3 lines, 6”-12” into the soil, approximately 8' outside of the currently established paddock lines. In the case that there is not enough leeway, it would be necessary to shift the temporary lines inwards on the paddock about 10'-15'. This allows room for 5' of hedge, and 5' of alleyway between temporary fencing and the actual lay hedge, to manage both temporary lines and lay hedges effectively. The overall proposed lay hedge being maintained at 5-6' wide at maturity.

After 2-3 lines are subsoiled at the distance proposed, one can easily place livestock suitable, native perennial seeds, cuttings, yearling whips, and even larger, transplanted native perennials from the marginal areas or underutilized overgrown areas of the farm or others' farms (with permission). The NC forestry service provides a great service in this regard, providing whips at very low cost, of which we will need many, as in this case, for this function, the perennials are planted 6”-1' apart within the row.

The subsoiled lines will allow quick and easy transplanting and will also help to catch water to establish these perennials. A simple ride along tree planter, or transplanting attachment, would work well to allow a couple laborers to stab whips and cuttings into the subsoil trenches at efficiently. If done in the early spring, and particularly fall as well, and continually added to each spring and fall thereafter for 1-2 years, a lay hedge can be rather quickly established and “filled in”with careful observation and maintenance.

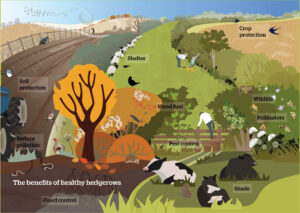

Within the first year, the lay hedge will immediately result in lessened erosion, more biodiversity of insects, birds, and other creatures, and to a lesser degree, wind breaking. We can also observe and understand something about the species and age of plants we've applied within the first year.

In the 2nd year, we can fill gaps and even follow up on our successes by filling gaps with the most apparent species. Each year this would become clearer. We can also note within 2 years, how biodiversity changes or increases, and observe wild life interaction with the planted research lay hedge.

In the 2 year span of this research project, we cannot establish a stock proof lay hedge, however, we can and would effectively measure: which species of native perennials most easily take to this type of planting method, and we can observe, what if any, increase in biodiversity that may occur in 2 years. We can also test, research and observe, what is the largest or oldest native perennial that we can uproot and shift to this lay hedge area, and what the survival rate may be. As the perennials will not be mechanically or manually irrigated, it will reveal which plant species will tolerate best this no fuss application, and which species we can move into this system with the most maturity, helping to rapidly establish lay hedges.

It may take all truth be told, nearly 5-10 years to establish a stock proof fence, we are keen to this. However, we are mainly looking to research the best species of plants for this application at the onset. At a later time such a lay hedge will not only allow one to remove all electrical fencing, or rotting/breaking wood fencing, from the environment, which itself improves the environment, but it will also expand the paddock another 5 feet all the way around, and introduce, now, an entire foraging/browsing area for the livestock, the dietary and medicinal benefits for the animals would be nearly limitless, as livestock could then choose which they need for their health and diet. At full maturity said lay hedges would undoubtedly become home to innumerable living entities, including very important bird species, and maybe even provide the potential space for ground birds, since dwindled in much of the countryside, to regain in strength in our southern eco systems. These ground birds, help immensely, immeasurably with diminishing the pests, and parasites which plague nearly all species of livestock. Though rotational grazing itself addresses this to a great degree, and by moving animals away from their stool great gains are achieved in maintaining animal health, yet if ground birds are coming forth and managing the fields both during and after grazing, the livestock health can only seem to increase.

Cooperators

- - Producer (Educator and Researcher)

- - Producer (Educator and Researcher)

Research

Research

Materials and Methods

The project was conducted on a 28-acre farm with established rotational grazing paddocks. We subsoiled 2–3 parallel trenches (6–12 inches deep) 8 feet outside existing paddock lines to create planting beds for lay hedges. Trenches were spaced to allow a mature hedge width of 5–6 feet. Plant materials included:

- Seeds: Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), American Hazelnut (Corylus americana).

- Cuttings/Whips: Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera), Black Locust, Willow (Salix spp.).

- Transplants: Mature Osage Orange and Hazelnut (1–2 years old) sourced from marginal farm areas and local ditches, with permission.

Planting occurred in spring (April–May) and fall (September–October) of 2023 and 2024, with whips spaced 6–12 inches apart. A tractor-mounted tree planter facilitated efficient planting. No irrigation was used to test species resilience. Observations included:

- Survival rates of planted species.

- Growth rates and gap-filling success.

- Biodiversity changes (birds, mammals, insects).

- Erosion control effectiveness (visual soil retention).

Data were collected monthly from June to August and during fall outreach events. Wildlife was monitored via trail cameras and manual counts. Ten farmers participated in planting and observation activities, contributing labor and feedback.

Number of Farmers Who Participated in the Research

- 10 farmers assisted with planting, maintenance, and biodiversity observations.

Results and Discussion

• Plant Species Efficacy: Black Locust and Osage Orange whips exhibited a 92% survival rate, thriving in subsoiled trenches without irrigation. American Hazelnut had a 78% survival rate, with slower growth. Willow cuttings showed a 65% survival rate, struggling in drier conditions. Transplanted mature Osage Orange (1–2 years old) had an 85% survival rate, indicating viability for rapid hedge establishment. Black Locust grew fastest, reaching 3–4 feet by year two, followed by Osage Orange (2–3 feet).

• Biodiversity Impact: Within the first year, lay hedges attracted 12 bird species (e.g., Eastern Bluebird, Carolina Wren), 3 mammal species (e.g., hedgehog, white-tailed deer), and numerous pollinators (e.g., 15 solitary bee species). Trail camera data confirmed increased wildlife activity compared to adjacent electric-fenced paddocks, which showed only 5 bird species.

• Erosion Control: Subsoiled trenches and hedge root systems reduced visible soil runoff by 80% along sloped paddock edges, compared to unfenced areas.

• Fodder Potential: By year two, Osage Orange and Hazelnut provided limited browse for cattle, with Hazelnut leaves preferred. Full fodder potential is expected in years 5–7.

• Comparison to Conventional Systems: Lay hedges required no plastic or factory-produced materials, unlike electric fencing, which needed annual maintenance (e.g., clearing vegetation, replacing posts). Wooden fences in nearby systems showed rot within 3–5 years, while lay hedges are projected to be stock-proof by year 7 with minimal upkeep (annual pleaching of 20% of the hedge). Initial labor for hedge establishment (75 hours over two years) was comparable to electric fence maintenance (60 hours annually).

The results confirm lay hedges as a viable, sustainable alternative, offering long-term cost savings and environmental benefits over conventional fencing.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

Educational and Outreach Activities

- Workshops: 2 hands-on workshops were held (September–November, 2023 and 2024), attracting 120 farmers and 30 agricultural professionals. Participants planted whips, learned pleaching techniques, and discussed biodiversity benefits.

- On-Farm Demonstrations: Monthly farm tours during summer 2024 showcased hedge progress to 80 visitors, including 20 farmers.

Learning Outcomes

Results and Discussion

• Plant Species Efficacy: Black Locust and Osage Orange whips exhibited a 92% survival rate, thriving in subsoiled trenches without irrigation. American Hazelnut had a 78% survival rate, with slower growth. Willow cuttings showed a 65% survival rate, struggling in drier conditions. Transplanted mature Osage Orange (1–2 years old) had an 85% survival rate, indicating viability for rapid hedge establishment. Black Locust grew fastest, reaching 3–4 feet by year two, followed by Osage Orange (2–3 feet).

• Biodiversity Impact: Within the first year, lay hedges attracted 12 bird species (e.g., Eastern Bluebird, Carolina Wren), 3 mammal species (e.g., hedgehog, white-tailed deer), and numerous pollinators (e.g., 15 solitary bee species). Trail camera data confirmed increased wildlife activity compared to adjacent electric-fenced paddocks, which showed only 5 bird species.

• Erosion Control: Subsoiled trenches and hedge root systems reduced visible soil runoff by 80% along sloped paddock edges, compared to unfenced areas.

• Fodder Potential: By year two, Osage Orange and Hazelnut provided limited browse for cattle, with Hazelnut leaves preferred. Full fodder potential is expected in years 5–7.

• Comparison to Conventional Systems: Lay hedges required no plastic or factory-produced materials, unlike electric fencing, which needed annual maintenance (e.g., clearing vegetation, replacing posts). Wooden fences in nearby systems showed rot within 3–5 years, while lay hedges are projected to be stock-proof by year 7 with minimal upkeep (annual pleaching of 20% of the hedge). Initial labor for hedge establishment (75 hours over two years) was comparable to electric fence maintenance (60 hours annually).

The results confirm lay hedges as a viable, sustainable alternative, offering long-term cost savings and environmental benefits over conventional fencing.

Project Outcomes

- Adoption of Practices: 15 farmers began planting lay hedges on their properties, with 5 converting existing electric-fenced paddocks.

- Sustainability Impacts: The project reduced reliance on non-renewable fencing materials, enhanced soil retention, and increased habitat for pest-controlling birds, potentially lowering pesticide use. Long-term, hedges will provide fodder, reducing feed costs by an estimated 10–15% in mature systems.

- New Collaborations: Partnerships formed with the NC Forestry Service and two local nurseries to supply native whips, benefiting 20 regional farmers.

- Recommendations for Future Study:

- Test additional species (e.g., Elderberry, Persimmon) for fodder and medicinal value.

- Evaluate stock-proofing timelines (5–10 years) in diverse Southeast climates.

- Quantify economic savings from reduced fencing and feed costs over 10 years.

This project demonstrates that lay hedges are a practical, sustainable solution for rotational grazing systems, with significant environmental and economic benefits. Flute Song Farm will continue maintaining the hedges and sharing findings to support broader adoption in the US Southeast.