Final report for FW16-042

Project Information

The summer season of 2016 marked the second year of trialing “Inherding” as a viable way to meet the growing complexities of grazing cattle on public (and private) rangeland. In concept, “Inherding” is quite simple. Rather than managing cattle with a “keeping out” paradigm and working to exclude livestock from sensitive areas, cattle are herded intensely to keep them “in” areas that have lower environmental sensitivity. 2016 trials also focused on whether herders could successfully target areas to be grazed, and if so, evaluate the potential of inherding to use targeted grazing to meet ecological objectives such as brush cover reduction.

Inherding trials were funded in 2016 by this SARE grant, a grant from the Central Idaho Rangelands Network, and matching funds from Alderspring Ranch.

The location for the Inherding Project is a 48,000 acre public range allotment consisting of Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management permits. Alderspring Ranch (Glenn Elzinga) is the sole permitee. The Allotment is remote, difficult to access, and difficult to manage due to steep topography and a number of conflicts that align with similar conflicts range managers are facing throughout the west: wolf reintroduction and pack increases causing increasing interactions with domestic livestock, fish listed under the Endangered Species Act, extensive riparian areas and many isolated riparian and spring “islands” essential for wildlife, potential big game wildlife conflicts, and recreation and hunting conflicts.

The summer season of 2016 also marked the addition of enforced standards and guidelines for grazing on public rangelands with sage grouse habitat as part of permit compliance. Based on our experience in the past with this allotment and others, it will be very difficult for permittees to meet these standards using old management tools. (See uploaded Forest Service 2016 Operating Plan for the Hat Creek Allotment fseprd508995 ).

The concept of “inherding” is an extension of the management intensive grazing paradigm that has been adopted by innovative stockman to increase forage production, vegetative health, and animal performance on pastures. In this management strategy, electric and permanent fencing is used to control animal movements, moving them as much as every day. This proposal extends this concept, but utilizes herders on horseback to control animal movement rather than fencing.

Inherding is simple in concept: ecologically aware riders herd cattle 24/7 to completely avoid sensitive areas, and select areas that are suitable for cattle grazing, watering, and bedding at night. All domestic livestock on the allotment are maintained in a single herd that is moved as a cohesive group across the landscape. The whereabouts of every domestic animal is known and controlled at all times. This is different from moving cattle out of sensitive areas, or moving them to a new area, "settling" them, and then leaving them. And it is different than "day riding" where riders locate cattle in the morning and move them to a new area. We tried these methods for over a decade on the Hat Creek Allotment, and found them unsatisfactory for meeting ecological objectives and animal welfare and performance objectives.

We coined the term “inherding” as a combination of “intensive herding” and as a change in paradigm from keeping cattle out of an area, as traditional range riders do, to the paradigm of keeping cattle in daily selected grazing paths and areas using stockmanship skills and herding.

Initially we conceptualized inherding as a way to eliminate livestock losses to wolves. Both because of personal appreciation for large predators, and because of a customer base that is willing to purchase our beef in part because we do not kill large predators, we were seeking a way to coexist with wolves on our wild mountain rangeland. Knowing that wolves will generally avoid humans, we decided to essentially live with our cattle, corralling them at night near camping cowboys and cowgirls in a temporary bedding ground surrounded by electric fence.

During the first summer we "inherded" (herded 24/7) in 2015, we found that wolf impacts were non-existent. But we found that we had something even more exciting. With herding, we learned that our control of animal location was complete. We could water them in very small, carefully selected watering sites where cattle would have minimal impact on streambanks. We could avoid springs altogether. These areas are typically magnets for cattle on the landscape, providing shade and water. Because these areas are so small and so attractive to livestock, they are nearly impossible to manage to avoid overgrazing. We could use bedding grounds to target areas where we wanted heavy disturbance or increased cattle manure. And we could limit utilization on upland key species to whatever we wished it to be. With herding, we used far more of the acreage of our allotment, bringing cattle to places they would never go on their own, but where there was great grazing. But with herding, we used all of our allotment much more lightly.

And we learned a few other things that first summer. We learned that we could completely avoid any losses to poisonous plants. We learned that we could use our herders to find weed populations (and document them with a GPS, and destroy them if small). We learned that the work requires a particular kind of person. We learned that it didn’t matter if other uses left the gates open on our fences; the fences were meaningless because our herders were the fences.

The 2016 project, in part funded by this SARE grant, built on what we learned about inherding during the 2015 grazing season. We needed more data.

We developed the following objectives for the 2016 field season:

• Train staff in ecological principles, stockmanship, horsemanship, monitoring, and horse packing.

• Implement ecological monitoring on the allotment to access ecological success of inherding.

• Implement herding and collect data on the level of control by herders.

• Identify issues associated with inherding that would limit adoption by others, and potential solutions.

• Track costs and benefits in order to economically assess inherding as a potential viable tool for range managers.

• Coordinate with stakeholders and potential partners.

• Disseminate information.

Research

In concept 24/7 herding is simple: riders remain with the cattle 24 hours a day, camping with them at night to protect from predators, and herding them during the day to meet ecological objectives and animal performance objectives.

In practice, it is much more complicated. Camps must be placed where the concentrated use of cattle, horses, and herders will not affect water quality or vegetation. We practice leave-no-trace camps, and siting of camps is critical to meeting that objective.

Water is a limiting factor. While the allotment has abundant water, in order to meet objectives of limited or no use of riparian areas and mesic meadows we had to develop systems for portable stockwater in camps that could be dismantled and removed, while meeting leave-no-trace objectives. We also had to train herders about the importance of avoiding mesic or riparian areas, crossing streams with minimal impacts, and maintaining watering systems.

Herding is more difficult than it may seem. Effective herding requires that staff not only be able to "read" the country ecologically and know which areas to avoid, and what level of grazing is appropriate, but it also requires that staff have the horsemanship and stockmanship skills to effectively manage the herd on the landscape.

These issues are discussed in more detail in the results section under "What We Learned."

Materials and methods for each specific objective given in the original proposal are described below:

Train staff in ecological principles, stockmanship, horsemanship, monitoring, and horse packing.

Training continued throughout the summer, but initial staff training involved 3 days stockmanship, horsemanship and packing, two half days on riparian and upland ecology and grazing, and one half day training in first aid and camp safety.

The riders have to function as "conservation riders" and need to be able to distinguish riparian areas and mesic meadows. Part of the initial training was an introduction to common riparian plant species.

Training staff in horse packing. Some of the camps are not vehicle-accessible, and camp equipment, electric fence, chargers, salt, and food have to be packed in with horses.

Implement ecological monitoring on the allotment to access ecological success of inherding.

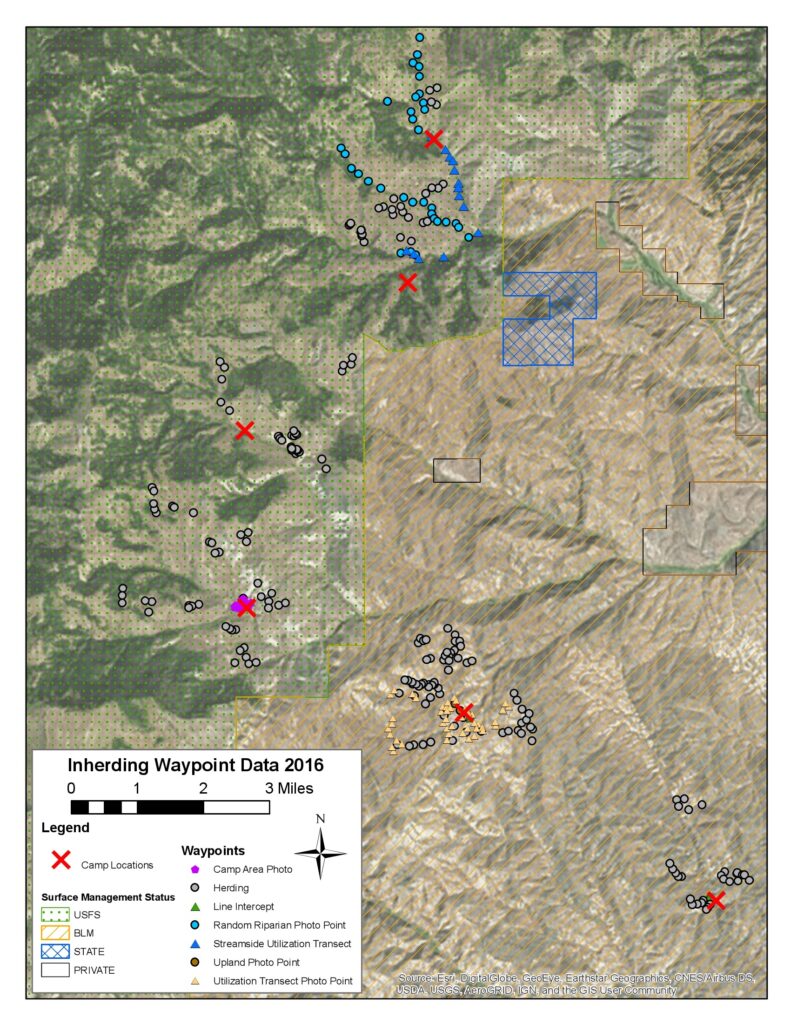

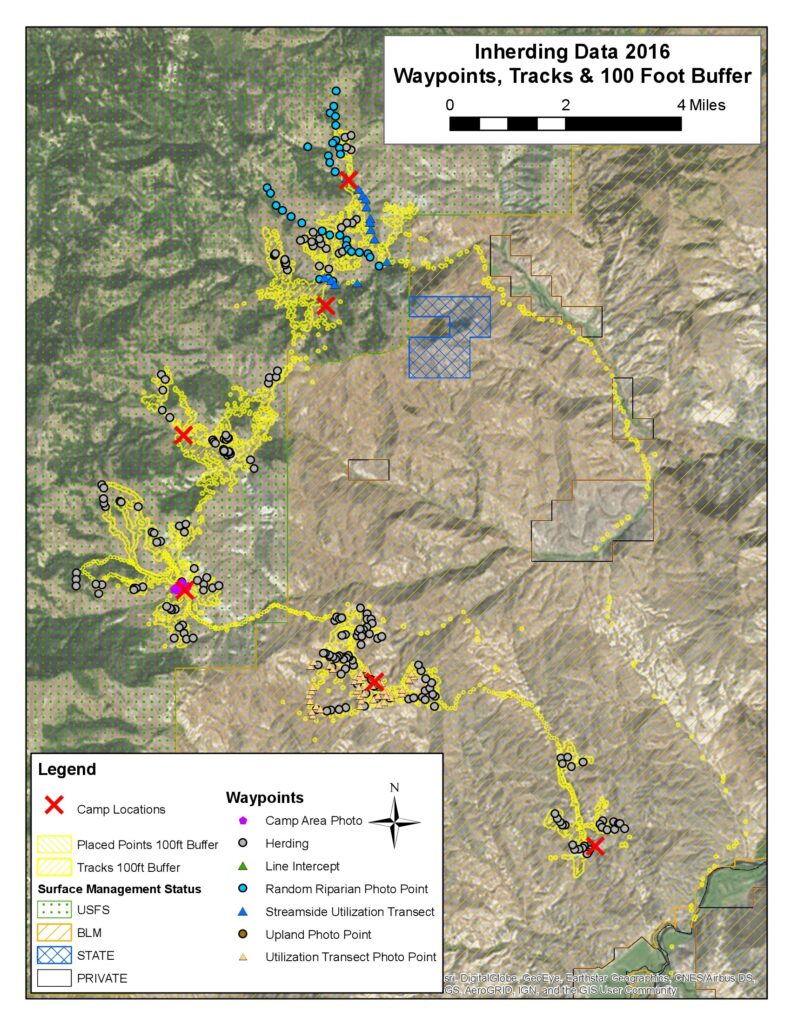

Monitoring in 2016 associated with this project included: GPS Tracking of cattle movement: every day except 5 days (equipment failure); establishment of 217 permanent photopoints, including 20 around camp areas to assess impacts; establishment of 32 riparian photopoints; line intercept/nested frequency sampling at two locations of previous 2015 camps; 19 utilization transects, with permanent photopoints; 51 streamside utilization/greenline transects. Locations of monitoring are shown in the aerial photograph below, and methods for each monitoring data set are described below the figure.

GPS tracking of cattle movement

We used relatively low-cost (<$200) Garmin GPS units, set to record tracks at 6 minute intervals. Two units were with the herding crew at all times, carried in a saddle bag. Each crew had a set of two units, and units were downloaded after every rotation to reduce chance of equipment failure. Tracks were organized and projected on aerial photo maps. Data gaps were filled from memory by herders in order to have a complete record of grazing pathways for the entire summer.

Permanent Photopoints.

These included upland photos, camp photopoints, and riparian photopoints. The upland points were taken ahead of the grazing herd to document plant community before grazing. Many of the areas grazed were likely never used by domestic grazers, or not grazed recently because of inaccessibility (e.g., steepness of slope or distance from water, limitations which can be overcome with herding). Riparian photopoints likewise were taken pre-grazing. Camp photopoints were established to document impacts and recovery from temporary cow camps and night pens.

Photo points were documented with GPS units. At each point 24 photos were taken in the 4 cardinal directions and the medians (NW, NE, SW, SE). In each of the eight directions a series of three photos were taken: horizon, mid, and ground. We have found the three shot series advantageous because the horizon shot helps with orientation, the mid shot allows for identification of plant community and plant cover, and the ground shot helps with species identification and bare ground assessment. In the office, all photos were geotagged, named by photopoint, and arranged into photopoint folders.

Upland Utilization

Utilization measures were completed using the landscape appearance method (Bureau of Land Management 1996), modified by including a GPS waypoint and a 24- photo series permanent photopoint with each transect to facilitate mapping and office evaluation. Utilization measures were taken in the pasture used for the longest time as a way of testing the effectiveness of herding to meet agency utilization standards.

These are the field crew instructions:

Equipment for each observer: camera, GPS unit, map of area, clipboard, pencils, utilization datasheets

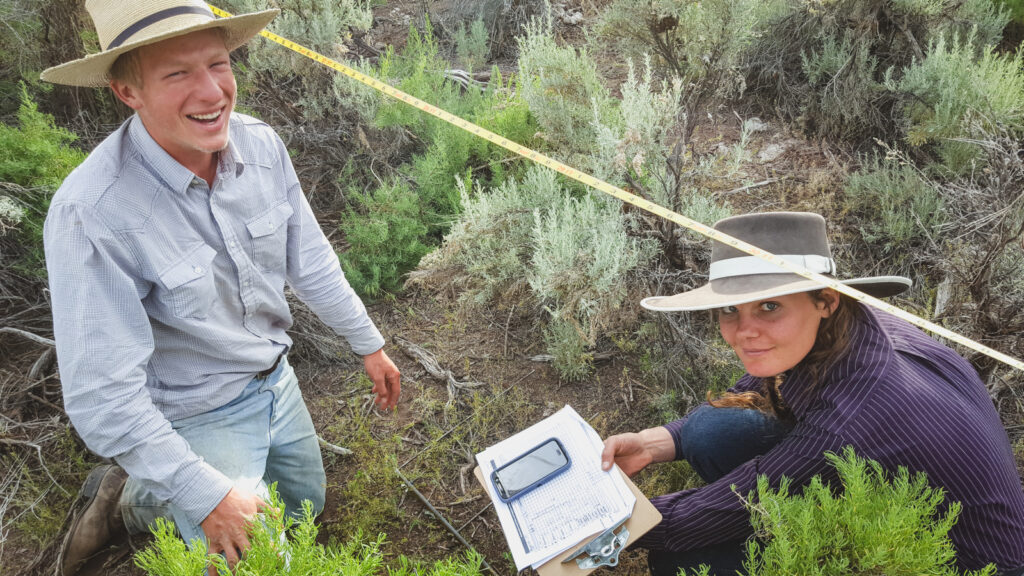

While you will generally being working as a team for safety reasons, utilization observations are most efficiently done as a single observer. You will split up but keep in visual contact with each other.

- Visually assess the area: topography, water, salt locations, fences, other impediments to livestock, shade, etc. Try to guess zones of likely use.

- Identify the key forage species (most likely blue bunch wheatgrass, Pseudoroegneria spicata, or Idaho fescue, Festuca idahoensis).

- Pick a spot to do your first transect (don’t stress too much about this, just start).

- Where utilization is minimal (less than 5%), you will simply note it as such and take one of our standard 24-photo-series photopoint. Do not complete an entire transect.

- Take a waypoint at the start of your transect and note it at the top of your datasheet.

- Take a standard photopoint at the start of your transect.

- Note waypoint on top of datasheet.

- Begin walking in the direction you think will be similar in utilization (same distance from water, same topographic position on hill, etc). Every 2 paces, assess the utilization on the key forage species using the classes in the datasheet. Record observations on the attached data sheet. You will take 50 points for each transect.

- Mark the end of your transect with another waypoint and photo series, and record on top of datasheet.

Streamside utilization/greenline transects

Greenline utilization transects are established at the intersection of live water and vegetation (Burton et al 2011). These are standard monitoring for agencies, but are not without observer error issues. This would be compounded by the fact that most members of our monitoring crew were relatively unskilled. In addition, greenlines can be slow to “read” and thus limit the number of sampling points. Our approach was to use a photographic sampling of the greenline that could be assessed in the office by an ecologist.

We also had a different objective than the standard greenline; we wanted to assess the percentage of stream miles affected by livestock . Prior to inherding, nearly every stream mile showed some level of impact from grazing on our allotment. We wanted to document how inherding changed that.

Our approach was to develop a random sampling of riparian utilization to answer the question of just what percent of the stream miles within the allotment were affected. Random sampling points were established using Google Earth and a free online tool as follows:

- Identify the area to sample.

- Use Google Earth to mark a rectangular area around your sampling polygon and mark the points at the corner.

- Use the rectangular option at http://www.zonums.com/gmaps/kml_rand.html and input the coordinates created in the step above. You can input the number of points you wish to generate. You will need to generate many more points than you plan to use because only a portion will fall on or near a riparian area.

- Open the file in Google Earth.

- Eliminate points on Google Earth that do not meet your criteria.

- Highlight the folder name of the randomly generated points in the sidebar of Google earth.

- File->save my place as -> file name.

- Go to http://garmin.gps-data-team.com/extra/.

- Put in the KMZ file into the browse box in the middle of the page and hit open.

- New window will have lat long; at the top of the page on right you can put in a new file name and select garmin gpx from the drop down list.

- Save it- it will go to your regular default download folder on your computer.

- Open the file in Mapsource. The locations will display as UTMs.

- Save that file as a txt file. You can now open it in excel. OR

- You can upload the Mapsource file to your GPS.

- Save Google earth images to print out and take to the field to help navigate to points.

We identified 51 sampling points. At each the observer noted if there was any utilization. If not, the observer would establish a 24 photo standard photopoint. If there was some evidence of cattle use, the observer would take a 100 pace greenline measure, taking a photo at each pace of the greenline. These photos were then assessed in the office for the percent of the greenline actually showing utilization.

Sampling at two locations of previous 2015 camps

One of the concerns that agency biologists have about inherding is the level of impact on night pen areas. Cattle are confined to a 2 acre or smaller night pen paddock with hot wire. Some of these paddocks were used for several days. The visual level of disturbance during that growing season is a little startling (one agency biologist called it a “crop circle”).

We sampled vegetation inside and outside one of the night pens used in 2015. We used a combination of line point intercept, Daubenmire frames of cover, density counts, and frequency counts in standard nested frequency plots (Coulloudon et al 1999). Baseline transects were monumented (so the sampling area can be resampled in the future). Sampling transects were randomly located along the baseline (Elzinga et al 1998). Along each sampling transect, several measures were taken. A point intercept sample of 50 points was taken along each sampling transect. Twenty standard BLM nested frequency frames of 50cm by 50cm (nested frames of 10x10cm, 25x25cm, 25x50cm, and 50x50cm) were placed every meter along the sampling transect. In each frame frequency was recorded by plot, following standard nested frequency protocol. Cover was estimated in the 25x50 plot, and density was recorded for the entire 50x50cm plot.

Implement herding and assess level of control by herders.

To ensure a high level of control, counts were completed during the day, and a count was done both in the morning when releasing cattle from the night pen and in the evening when moving cattle into the night pen.

Identify logistical and personnel issues associated with Inherding, and potential solutions.

Throughout the summer, notes were maintained on logistical issues and solutions suggested by the crew. Each crew member also had a lengthy closeout where suggestions for improvements were captured.

Track costs and benefits in order to economically assess Inherding as a potential viable tool for range managers.

Costs were tracked both in terms of labor and in terms of supervision and equipment costs. Staff daily logged the time spent doing the various tasks associated with the project in order to track allocation of effort to monitoring, supervision, camp moves, etc.

Coordinate with stakeholders and potential partners.

During the field season, we held two well-attending field tours (20-35 individuals at each), in spite of the remote location. Attendees included other permitees/ranchers, agency personal (including the Forest Service District Ranger), a representative from the Idaho Office of Species Conservation, local county employees, a nationally known grazing consultant, and several young technicians.

The late summer tour was accessible by 4x4 vehicle, and had good attendance by a diversity of stakeholders and interested parties.

The fall tour was conducted on horseback. Participants included two communications specialists, several NGO and agency representatives, and our county extension agent.

Disseminate information.

In addition to the two on-site tours described above, we spent a day with each of two journalists, and the Nature Conservancy’s World Communication Director attended our second tour. We gave presentations to the Central Idaho Rangelands Network (with attendance by representative from the Lemhi Regional Land Trust, the Wood River Land Trust, and The Nature Conservancy), and to the Idaho Center for Sustainable Agriculture annual conference to an audience of over 150. Additional coordination and information sharing occurred during several meetings with Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management biologists and managers.

REFERENCES

Burton, T.A., Smith, S.J. and Cowley, E.R., 2011. Riparian area management: multiple indicator monitoring (MIM) of stream channels and streamside vegetation. Technical Reference 1737-23. US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, National Operations Center, Denver, CO. www.blm.gov/nstc/library/pdf/MIM.pdf

Bureau of Land Management, 1996. Utilization Studies and Residual Measurements. Interagency Technical Reference 1734-3. Cooperative Extension Service. US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior. https://www.blm.gov/nstc/library/pdf/utilstudies.pdf

Coulloudon, B., Eshelman, K., Gianola, J., Habich, N., Hughes, L., Johnson, C., Pellant, M., Podborny, P., Rasmussen, A., Robles, B. and Shaver, P., 1999. Sampling Vegetation Attributes. Interagency Technical Reference 1734-3. Cooperative Extension Service. US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior. https://www.blm.gov/nstc/library/pdf/utilstudies.pdf

Elzinga, C.L., D.W. Salzer and J.W. Willoughby. 1998. Measuring and Monitoring Plant Populations. Technical Reference 1730-1. Bureau of Land Management. Denver, Colorado. USDI, BLM https://www.blm.gov/nstc/library/pdf/MeasAndMon.pdf

We exceeded all Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management standards and guidelines for 2016. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management employees and managers are very interested in our project, and are on board to partner with us during the field season of 2017. The Forest Service conducted additional monitoring to ensure that we were actually meeting our objectives, and were pleased with the results. They plan to use this allotment as a test allotment for sage grouse habitat assessment and monitoring, expanding on the partnership we established with them over the past few years.

Specific results for each of the objectives of the project are as follows:

Train staff in ecological principles, stockmanship, horsemanship, monitoring, and horse packing.

Teams of herders for inherding need to incorporate a range of skills for success. Individuals must have and understanding of the ecology of riparian areas and native range plants in order to make judgements in the field about which areas to avoid and how long to allow animals to graze in a particular area. Individuals must also be able to ride a horse in difficult terrain. Herders must have some skills for living outside for extended periods. And finally, herders must be able to “read” cattle and adjust their trajectory and movement across the landscape.

For 2017, we are planning additional training in all of these areas, especially targeting further education in monitoring and ecology. Ecological understanding was the greatest staffing shortfall; getting the team to grasp the functionality of rangeland systems was difficult in spite of having individuals on each herding team with ecological college degrees.

Stockmanship is also a critical skill, and at least one person on a team must have skill and experience moving cattle. The Hat Creek Allotment is remote, rugged, and steep, and moving cattle in a controlled way through such a landscape is not easy. We were unable to fill all of these positions with individuals knowledgeable about stockmanship, and were forced to hire from within our regular staff, creating staffing shortfalls on the home ranch.

Training included 2 days of stockmanship school. While this was adequate for team members, it was inadequate for team leaders/crew bosses. We ended up adding knowledgeable individuals from our home ranch staff.

The difficulty of locating individuals with these skills was discussed by members of the Central Idaho Rangelands Network (CIRN), and there is talk of creating a “conservation rider” career path in cooperation with the University of Idaho. Brainstorming sessions by the group have resulted in a list of desired skills and abilities for a conservation rider, and a committee is developing a more extensive list. University of Idaho, The Nature Conservancy, and the CIRN have already worked on some projects together, and this is a reasonable extension of that relationship.

Implement ecological monitoring on the allotment to access ecological success of inherding.

GPS tracking of cattle movement

Using the handheld Garmin units was a low-budget way of tracking cattle movement and was effective. It did, however, require significant post-processing time in order to generate a useful set of data points and maps of the area. Ideally, cattle would be fitted with tracking collars similar to those used in wildlife studies. This would eliminate operator error in remembering to turn on or take along the GPS units, and would make processing easier because each unit would produce a single file, rather than the multiple files that our approach created, all of which had to be manually put together and scanned for duplication.

Maps prepared from this data are very useful. Never before has the information about where exactly cattle grazed within the 70 square miles of the Hat Creek Allotment been available. The information is very useful to biologists monitoring wildlife and fish habitat on the allotment to know where to target their efforts. It was also useful to us as operators on the allotment working with resource specialists for each agency to plan grazing for the 2017 field season.

Results of GPS data tracking by herders. Boundaries in yellow are 100 ft buffers around tracks, and represent a reasonable estimate of the areas that were grazed during the 2016 grazing season. These data are only useful because the herd was kept together throughout the grazing season. No other cattle grazed the allotment, and the location of every beef animal on the allotment was known at all times. The herd essentially followed a clockwise pattern around the allotment, moving from low country to higher country as lower elevation forage cured. Elevation gain was approximately 4000 ft. The entire center of the allotment was ungrazed.

Permanent Photopoints.

The 249 permanent photopoints established as part of this study- upland, camp areas, and riparian- bring the total number of permanent photopoints on this allotment to over 600. No other allotment in Idaho has this extensive of a photographic record of range conditions, and the points are well distributed over the allotment. While no interpretation was done as part of the 2016 work, the photopoints will provide an extensive qualitative data base of the condition of the allotment for future reference.

These photopoints are unique in that each photo is geotagged with the UTM location of the photo. In addition, the full series of 24 photos taken at each photopoint allows for interpretation of plant community composition and ground cover. This is in contrast to typical rangeland photopoints that often only have one or a few photos associated with the photopoint, a holdover from earlier days when photo points were recorded with film, and were expensive to process and curate.

Upland Utilization

Typically, utilization patterns are heavily influenced by water locations and slope. Inherding changes that.

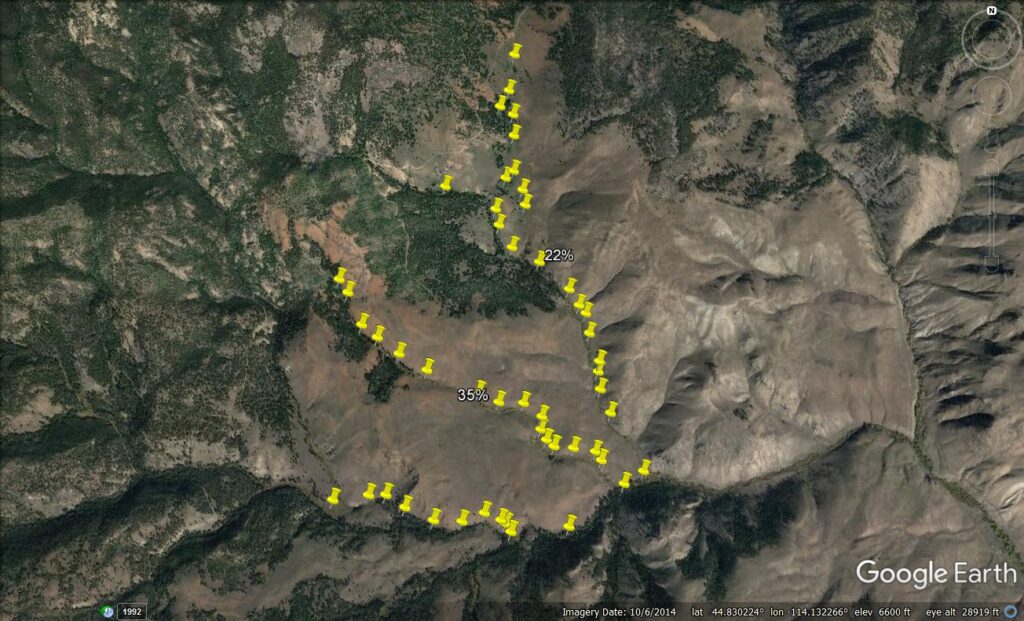

The image below is from the Bear Basin pasture. No live water, riparian vegetation, or mesic meadows occur in this pasture. The only source of water is a tank, depicted by a red dot. Around the tank is the "night paddock," where cattle are confined during the night hours, and where they access water during the day. The night paddock is depicted by a green rectangle. This paddock is constructed of two strands of electric fence (hot and ground), charged by a solar powered energizer.

Thumbtacks represent the start and end points of utilization transects. The numbers associated with the transects are the utilization level on the key species, bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata). The same utilization number is associated with the start and end of the transect, so transect location and direction are shown by those matching numbers.

Utilization levels ranged from a high of 59% to a low of 3% and clearly do not follow typical utilization levels that occur when cattle are simply left in a pasture (very heavy use near the water, light or no use further out). Our goal for this project was to maintain 30% or less utilization but there are some lessons in the pattern and the areas of use that were higher than our goal.

Cattle were typically taken from the night pen and moved northwest along the two track leading from the water tank. The crew had been told that no grazing could occur east of the road, and utilization measure there showed that they heeded that directive, with utilization below 4% (likely grazed by native ungulates). To avoid this area the typical daily path to reach grazing to the north and west was to move cattle northwest along the road and then southwest up the draw. The other common path was to continue past the draw and then west through the area marked by the turquoise circle. These data made us realize that we had to think harder about ingress and egress from the night paddock, and in 2017, we planned movements from night paddocks in order to avoid higher levels of utilization along paths radiating from the night paddock.

These utilization data also demonstrated that crew members needed training in getting an "eye" for utilization levels, so that they could move cattle on once limits were approached. Nearly all of the crew participated in capturing utilization data for this pasture, which gave them a sense of what various utilization levels looked like on the ground as the remainder of the season progressed.

Streamside utilization/greenline transects

Of the 51 randomly located utilization sampling locations shown in the map below, only at two locations was there measurable domestic livestock use. The 22% location shown in the map below is in a water gap area, and a portion of the transect was used as a deliberately placed and fenced water gap (approximately 1/5 of the sampled stream length). The 35% transect shown on the map was a crossing spot chosen to impact riparian values as little as possible. The remaining locations showed no domestic livestock use.

It is important to note that the locations showing livestock use were ones that had been deliberately planned, and were judged to be areas where use would minimally affect riparian attributes. The purpose of using a random sample of all available riparian areas was to demonstrate that in spite of grazing much of the allotment, the only locations where cattle used riparian areas were areas that were selected. The sampling clearly demonstrates the success at meeting this objective.

One non-riparian observation is worth noting. Standards for sage grouse not only address riparian vegetation along streams, but also include mesic meadow vegetation. We avoided these areas through herding, but on the tour with agency biologists we examined several of these mesic meadows. None of them made standards, which means we were technically in violation of our permit stubble height standards for these areas. The culprits, easily identified by scat, were native elk, not cattle.

Sampling at Previous 2015 Camps

Visually, the difference at the sampled site between inside and outside the Bear Basin Pasture night pen one year after use was barely detectable. Point line intercept found minimal differences between litter and canopy cover. Basal cover was significantly less within the night pen, but bare ground was also less (Table 1. Both significant at p=0.10). More cushion type plants that provide both canopy and soil surface coverage (Phlox hoodii, Happlopappus uniflorus, Eriogonum cespitosum, Penstemon aridus) occurred outside the night pen, but this seemed to be a natural distribution rather than one caused by cattle. Similar higher density areas of these plants occurred within the night pen, suggestion soil features likely caused the pattern.

Table 1. Canopy cover, percent bare ground (with no cover at all), basal vegetative cover, and litter values inside and just outside the night pen at Bare Basin Pasture. (* p=0.10, n=5)

| CANOPY | BARE | BASAL | LITTER | |

| night pen | 34 | 45.6* | 8.4* | 21.4 |

| outside | 34 | 50.4* | 16.8* | 24 |

Plant composition measurements of frequency, density, and cover showed no significant differences between the area used as a night pen in 2015, and vegetation ungrazed in 2015 immediately outside the night pen. While there may have been some differences that would have been detected with a higher sample size (n=5), it could be argued that these differences would not be ecologically meaningful anyway. Table 2 shows results for frequency.

Table 2. Percent frequency inside and outside the night pen at the Bear Basin Pasture for the three primary species of bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), and three-tipped sagebrush (Artemisia tripartita).

| Night pen | Ungrazed | |

| Bluebunch Wheatgrass | 26.6 | 24.4 |

| Idaho Fescue | 57.2 | 58.4 |

| Three-tip Sage | 64 | 60.2 |

While results for the night pen at the Bear Basin Pasture showed little difference inside and outside the night pen, observations at other camps where the night pens were smaller and sites less harsh did demonstrate a visual difference. The photos below show the vegetative response at the Big Hat Camp. Plant composition remained similar, but plant vigor and cover were clearly higher within the night pen area compared to the plants just outside the night pen.

This suggests that although night pens appear heavily disturbed immediately after use, recovery the following year is complete.

Vegetation inside the 2015 night pen photographed early July 2016. Plants are perennial natives.

Vegetation just outside the 2015 night pen, photographed in early July 2016. Photo is approximately 20 feet away from the night pen photo above.

Implement herding and assess level of control by herders.

This was considered a complete success. No cattle were lost, cattle were controlled 100% throughout the entire grazing season, no losses occurred due to poisonous plants, no wolf interactions occurred, and no unplanned use of riparian or spring areas occurred.

One of our objectives on this allotment since we began using it in 2005 was to encourage recovery of aspen stands, many of which were comprised of decadent old even age overstory and a continually browsed understory. Throughout much of the allotment aspen regeneration is now above browse height for cattle. This picture also shows that with inherding, areas with abundant deadly larkspur (the bright blue flower in the picture) could be safely grazed. These stands are grazed quickly and lightly and we observed that cattle actively avoid larkspur as long as there is abundant alternative forage available.

Track costs and benefits in order to economically assess Inherding as a potential viable tool for range managers.

Costs were tracked for labor and equipment costs throughout the summer of 2016 and into the fall.

Table 3. Inherding costs by activity for labor.

| Task | Total | Class total | Class |

| Range Project Tour/ Promotional Work | $5,844.32 | ||

| Project Photography and Videography (Non Monitoring) | $1,714.15 | $7,558.47 | communication total |

| Camp Construction | $2,760.48 | ||

| Switch Days | $17,283.01 | ||

| Cattle Herding | $23,946.94 | $43,990.42 | herding implementation |

| Hauling Cattle Back to Ranch | $948.88 | ||

| Tack Organization & Maintenance | $406.29 | ||

| Range Infrastructure Maintenance | $2,481.10 | ||

| Equipment Maintenance & Research | $689.54 | ||

| Scale Construction | $861.04 | ||

| Horse Upkeep | $385.31 | $5,772.15 | logistics |

| Weighing Cattle | $985.16 | ||

| Photopoint Monitoring | $1,144.92 | ||

| Utilization Monitoring | $712.02 | ||

| Bedding Ground Monitoring | $2,024.24 | ||

| Transect Generation | $201.00 | ||

| Streamside Monitoring | $1,236.48 | ||

| Data Processing | $1,637.76 | $7,941.58 | monitoring |

| Monitoring Training | $939.17 | ||

| Packing Training | $1,456.80 | ||

| Stock Handling Training | $2,109.73 | ||

| Horsemanship Training | $628.63 | ||

| Horse Training | $806.20 | $5,940.53 | training |

| Grand Total | $71,203.15 |

Table 4. Inherding Costs: Supplies and Equipment

| Class | Travel/Equipment/Supplies | Total | Amortize | Class Total |

| logistics | Camp equipment purchase: tent, stove, lanterns, fuel | $ 650.00 | 2 year life | |

| logistics | Hot wire, charger, battery, solar panel | $ 500.00 | 2 year life | |

| logistics | Shoe horses | $ 1,100.00 | annual | |

| logistics | Water filtration systems | $ 175.00 | annual | |

| logistics | Fix tack | $ 300.00 | annual | |

| logistics | Hobbles | $ 300.00 | 4 year life | |

| logistics | Protein for happy team members- wholesale price | $ 1,350.00 | annual | |

| logistics | Scales- fix, pour concrete, get inspected | $ 500.00 | once | |

| logistics | Create temporary housing for expanded staff | $ 2,000.00 | 2 year life | $ 6,875.00 |

| monitoring | Monitoring equipment: 3 cameras, 2 gps, 3 tapes | $ 1,150.00 | 2 year life | |

| monitoring | Monitoring supplies: thumb drives, sd cards, stakes and markers | $ 225.00 | annual | $ 1,375.00 |

| herding | Trailer trips to swap team and horses | $ 1,950.00 | annual | |

| herding | Move camps, replace propane, fix equipment, pack horse rental | $ 1,150.00 | annual | |

| herding | ATV days | $ 1,125.00 | annual | $ 4,225.00 |

| communications | Travel- interact with FS and BLM | $ 300.00 | annual | |

| communications | Travel- present at Idaho Sustainable Ag Conference | $ 350.00 | annual | |

| communications | Tour hosting costs: horses and trailers | $ 350.00 | annual | $ 1,000.00 |

| training | Trainer direct cost | $ 800.00 | annual | $ 800.00 |

| TOTAL FY 2016 supplies and equipment | $ 14,275.00 | |||

| Amortized FY 2016 portion | $ 11,900.00 |

Table 5. Summary of costs by class for inherding in 2015.

| Supplies | Labor | Total | |

| Logistics | $ 4,075.00 | $ 5,772.15 | $ 9,847.15 |

| Monitoring | $ 800.00 | $ 7,941.58 | $ 8,741.58 |

| Herding | $ 4,225.00 | $ 43,990.42 | $ 48,215.42 |

| Communications | $ 1,000.00 | $ 7,558.47 | $ 8,558.47 |

| Training | $ 800.00 | $ 5,940.53 | $ 6,740.53 |

Total costs in 2016 (using amortized values for some of the supplies) is $82,103.15. Total number of head of cattle grazed was 210 and the average daily gain was 1.52 lbs/day over a 95 day grazing season.

Excluding costs that were not directly a part of herding and animal care and summing up only costs classified as logistics, herding, and training, the total cost of inherding in 2016 was $64,803.10, or $3.25 per day per animal.

Clearly the model implemented during our pilot project is in no way cost effective in comparison with private pasture rates of approximately $1.00/ day. But there are several factors that can be changed that may make inherding more competitive with private pasture rates:

- Increase number of head. All herders agreed that 2-3 times the number of livestock could be controlled with the same number of herders. This change alone would bring costs closely in line with private pasture rates.

- Increase gain. 2016 was a very dry year. Forage cured early, water systems were inadequate, and cattle were not watered sufficiently. Daily average gains of 1.5 lbs is disappointing. Changes made for the 2017 grazing season in water systems and camp locations should improve weight gains.

- Decrease costs. The allotment in which inherding was trialed is one of the most difficult grazing ranges in central Idaho. Access is very poor and vehicle access requires over an hour of travel over very poor roads, thus increasing costs for time, vehicles, and other equipment. While the nature of the allotment is obviously not going to change, there are opportunities to reduce these costs. In 2016, crews were switched every three days. This will be increased to four days in 2017. Horses will be kept in larger paddocks in camp for most of the summer, thus reducing trailer trips with horses. Teams will generally be 2 person rather than 3 person teams as they were in 2016. Through changes in camp locations and the addition of stock dogs, 2 people can provide adequate control, even with additional cattle. Training costs can be reduced by forgoing the pre-herding training (about a week in 2016), and replacing it with on the job training during the first 2 weeks of herding.

Coordinate with stakeholders and potential partners / Disseminate information.

Coordination and information sharing is a never-ending task, so it is difficult to assess success. Three operators from a 3 state area are asking for guidance from us on how they can implement the inherding concept on their ranges in 2017. We hope with the additional press in the next few months that we will have more interest.

A few members of the Central Idaho Rangelands Network were so interested in the project that they proposed we develop an “ecological range rider” job description and proposed curriculum to bring to state universities.

The Idaho Office of Species Conservation recognized that the inherding approach was a potential solution to predator conflicts with ranchers, and partnered with us to implement inherding for the 2017 grazing season.

What We Learned

The closeout sessions with the crew, and additional discussions during the fall and winter, yielded valuable insights. These are summarized here.

About Camps

The camps provide a base of operations for grazing and herders. Camps included a human area with a tarp "cook shack," small backpacking tents, and in some camps a fire ring (for part of the summer before fire restrictions on public lands). Gear included: small propane cook stove, hard-sided bear-proof camp cooler (stayed in camp), first aid kit, GPS hard sided storage containers, camp chairs, camp table, lantern, clothesline, bear line and bear bag, sleeping pads in the tents. Herders brought their own food, clothes, sleeping bag, and tack on each switch cycle. All herders agreed that the camps were adequate and comfortable for the riders.

Camps were designed to be leave-no-trace. At the end of a camp's use, all equipment was removed, the fire ring dismantled, and the area raked.

Camps also included a horse area that was large enough to include good grazing and an access to water- either a tank or a small water gap. Horses needed to be able to eat in their grazing pen, since some horses were used for a few days in a row. Horse pens were constructed with single wire hot wire. Depending on the horse, animals that were not be used were sometimes allowed to roam freely with the herd for the days graze. Some horses required confinement because they knew the way home, even though it was 20 plus miles to the home ranch. Herders agreed that horse pens were sometimes inadequate to provide enough forage for horses to maintain body condition.

Camps also included a night pen for cattle. In some camps, these could be sited in dark timber that naturally had deep duff and little ground vegetation. These areas could be raked and reclaimed at the end of the use period with little visual evidence left to a casual observer. In other camps, night pens were constructed in sagebrush/ grass plant communities, and the physical impacts of woody plant breakage and ground trampling created a visually obvious use area- but only for the remainder of that growing season. By the following growing season, these areas had recovered, and actually looked "better" than areas outside of the night pens. Night pens remain, however, the most difficult aspect of this project for agency personal to accept, in part because of the visual impact, but also because of the requirements for outfitters to leave no trace of their stock.

About Water

Water remains a difficult issue. There are limited off-stream water developments within the allotment. While one of the objectives of the project is to minimize use of riparian areas and springs, cattle performance is also critical to the economic success of the project. In 2016, weight gains were impacted by lack of water. If the project is going to continue to limit livestock access to natural water, more water developments are needed. In 2017 we will be experimenting with temporary water systems that keep cattle from riparian areas while providing adequate water for good weight gains and cattle health.

About Herding Crews

Stockmanship training on the open meadows of the home ranch failed to provide necessary skills for herding cattle on the more difficult country of Hat Creek Allotment. Staff suggested to possible solutions. The first was to set up an obstacle course on the home ranch that would test some of the stockmanship skills taught during training. The second was to have the entire staff work on the range for the first week or two, with experienced herders working one on one with new hires. All agreed that it was unreasonable to expect the crew boss to be both in charge of moving cattle, and watching and correcting new staff on stockmanship during the first few weeks.

Herding can be done with 2 people and a couple of good dogs, but three people provides more control and flexibility.

Ecological training is too complex for new hires, who are also learning herding, horsemanship and stockmanship. Crew bosses should receive ecological training before the field season starts, and then communicate that knowledge to teams while on-site.

We found crews comprised of both men and women to be more effective than crews comprised of a single gender.

In Summary

Results from 2016 were encouraging enough to pursue continued efforts with the project in 2017. We will continue to adapt the model to improve the economic feasibility, while meeting ecological objectives. It is our hope that the model can serve to demonstrate that full time herding can transform domestic cattle from a negative impact on western wildlands to being recognized as a potentially powerful ecological tool.

Research Outcomes

Education and Outreach

Participation Summary:

Consultations: by phone, three different operations, one of which is a very large operation in Nevada that was inspired to try inherding based on the presentation at the Idaho Center for Sustainable Agriculture.

Published Articles:

Can Ancient Herding Traditions Help Cattle Coexist with Wolves and Sage Grouse? 2017. Matt Miller. Cool Green Science. The Nature Conservancy Blog. http://blog.nature.org/science/2017/03/21/ancient-herding-traditions-cattle-coexist-wolves-sage-grouse/

Alderspring Ranch: Where new cowhands learn old tricks. 2016. Edible Idaho. http://edibleidaho.ediblecommunities.com/food-thought/alderspring-ranch-where-new-cowhands-learn-old-tricks

Making the most out of organic market. 2016. Melissa Hemken. Western Farmer Stockman. http://www.westernfarmerstockman.com/story-making-organic-market-9-146280

Ranching with a Smaller Hoofprint. 2017. Matt Miller. The Nature Conservancy Magazine, Summer. Pg. 62.

Blog posts on Alderspring Ranch Blog, Organic Beef Matters:

- A Rough and Rainy Ride on the Range. http://www.alderspring.com/organic-beef-matters/rough-rainy-ride-range/

- Regenerating Rangelands, Reinventing Grass Fed Beef. http://www.alderspring.com/organic-beef-matters/regenerating-rangelands-reinventing-grass-fed-beef/

- Riding the Alderspring Range Isn't Always Easy. http://www.alderspring.com/organic-beef-matters/riding-alderspring-range-isnt-always-easy/

- Herding Alderspring Beeves to New Range Pasture. http://www.alderspring.com/organic-beef-matters/herding-alderspring-beeves-new-range-pasture/

Tours

Cindy Salo, science writer (June 16, 2016)

Public Range Tour (August 16, 2016. Attended by representatives from the Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service, Salmon Valley Stewardship, Central Idaho Rangelands Network, American Grazing Lands, Idaho Office of Species Conservation, and several members of the public.)

Agency and media range tour (September 22, 2016. Attended by representatives from The Nature Conservancy, the Forest Service, University of Idaho Extension, writer from Western Horseman (article to be published Fall 2017) and Bureau of Land Management.)

Presentations:

Idaho Center for Sustainable Agriculture (December 3, 2016; approximately 60 producers, NGOs, and agency participants)

Central Idaho Rangelands (January 24, 2017; 5 NGO participants and 8 rancher participants)

Central Idaho Rangelands (March 2, 2017; 5 NGO participants and 9 rancher participants)

Education and Outreach Outcomes

2016 was the second year of trialing the concept of full time 24/7 herding (inherding) as a way to address ecological and political issues on public range allotments (and perhaps for private). Ecological and management objectives were met or exceeded. The approach works to meet grazing standards for endangered and sensitive species as well as eliminate losses from poisonous plants and predators.

Two issues will need to be resolved to encourage more widespread adoption.

First is financial. The inherding model as we have implemented it in 2015 and 2016 is not financially viable. Future years of inherding will focus on increasing weight gains, increasing the number of cattle within a herd without adding additional herders, and lowering costs.

Second is logistical and political. Inherding would function most efficiently if there were permanent night ground pens with reliable sources of water. Much of the costs identified in 2015 and 2016 are related to constructing temporary night holding pens and creating temporary water sources and then breaking down camps and water systems in a "leave no trace" approach. Constructing permanent camps would require a political change in thinking about how to manage livestock use on public lands, but the trade-off would be reducing or eliminating pasture and allotment boundary fencing (which can cause sage grouse mortality as well as visual impacts in semi-wild areas).