Final report for FW19-340

Project Information

Improving Winter Greens Production and Storage for Cold Climate Farmers is a three year project designed to provide Northern US growers with profitable solutions for winter production challenges and to provide their communities with nutritious local food year round. Western Montana and regions with similar plant hardiness zones currently face limited options for fresh produce in the winter months. Greens available in our stores and restaurants have traveled many miles and many days, resulting in low quality food with no economic benefit to the local community. On the other side of the equation, many vegetable producers in Montana have the infrastructure but lack the knowledge and technology necessary to successfully grow year-round, and their businesses suffer seasonal gaps in farm income starting soon after field crops freeze. Producers and researchers in areas in the northern US such as Vermont and Michigan have pioneered methods that may be very applicable to our growing climate but also may require adaptations which we hope to explore and share.

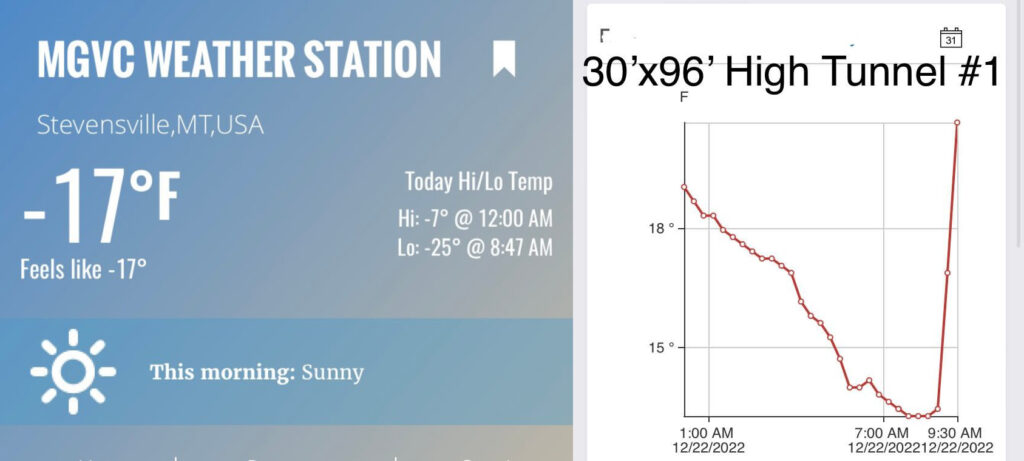

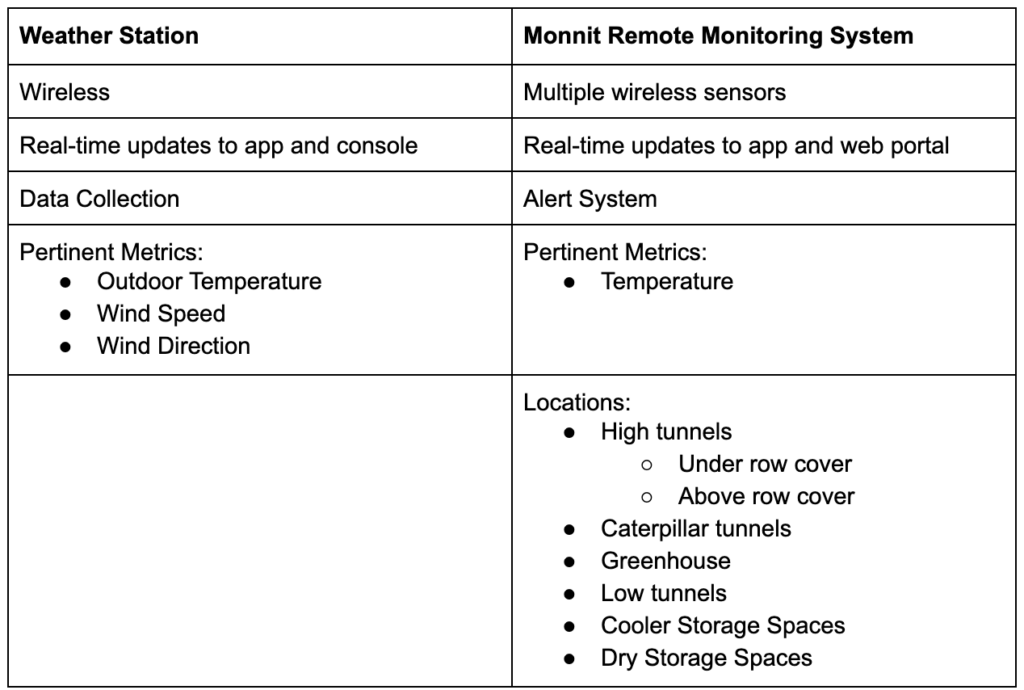

This project researched cost-effective methods of high tunnel ventilation, efficient passive solar heating, high-yielding and cold-hardy greens varieties, and optimal storage practices. Missoula Grain and Vegetable Co., LLC (MGVC) constructed four caterpillar tunnels - which are smaller and more mobile than high tunnels - to test alongside three stationary high tunnels at the farm. MGVC erected a weather station on the farm and added temperature sensors to the high tunnels and one caterpillar tunnel. Finally explored ways to make winter-produced crops last longer in storage by tracking how a green spinach variety fares in storage for short and long durations. All results have been made available online through a video summarizing our findings. Our findings were also shared at farm tours, on-farm and online workshops, and through social media interactions with interested Northern producers.

Project Objectives:

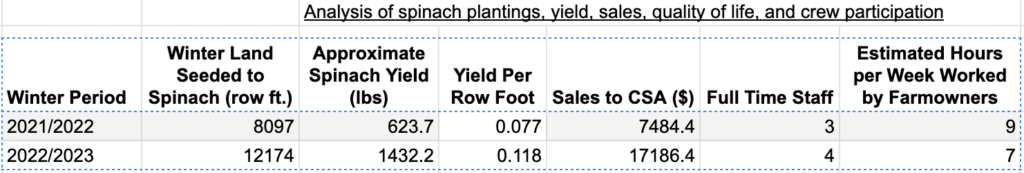

- Strengthen the competitiveness of Montana vegetable farms by researching improvements to the production and profitability of winter-grown greens. To measure this goal, we will track input and yield data from multiple high tunnel systems and variety trials. After presenting this information in workshops, farm tours, and at conferences, we will use surveys to determine its value to participating farmers and to identify additional areas of need.

- Improve efficiency of high tunnel ventilation and crop frost protection, conserving both fossil fuel and labor resources. Measured by tracking labor costs and yields for our 6 production spaces, and comparing the results between multiple methods and technologies. Results will be shared with other growers at tours, workshops, conferences, and in published articles.

- Enhance quality of life for farmers by demonstrating lucrative opportunities for winter farm income. This goal will be measured by tracking profits and progress towards less expensive inputs, shorter working hours, and the ability to fund additional staffing at the farm. We will measure increased awareness of strategies for producing and storing high-value winter greens through surveys for tour and workshop participants.

- Provide local consumers with fresh, local produce year round. Measured through leaf tissue analysis of winter-produced greens under different storage conditions and duration.

July-September 2019: Install four 24' x 150' Caterpillar tunnels with convection heating system

July-September 2019: Order seeds for lettuce variety trials

August-October 2019: Install temperature and humidity sensors on high tunnels and weather station at MGVC

August-October 2019: Install solar-powered ventilation systems

Beginning November of 2019 through June of 2022: Small-group farm tours, 4+/year

February-March 2020, 2021, and 2022: Compile the previous season’s data on production costs, harvest volumes, and weather for all winter greens production; analyze for effects of climate conditions, high tunnel heating, and seed variety

July 2020: Field Day farm tour at MGVC with Missoula CFAC

July 2020, 2021, and 2022: Present project at WARC field day

December of 2021: On-farm Winter Production Workshop

December 2021: Present project at MOA Annual Conference

2020, 2021, and 2022: Publish one or more articles about project and results each year

January 2022-March 2022: Compile data and results into final write-up

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

- - Producer

- - Producer

Research

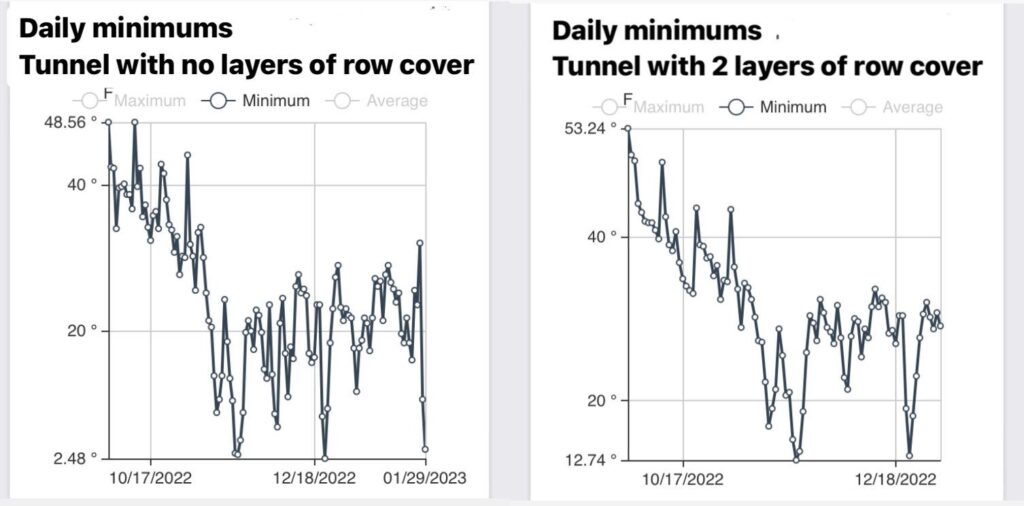

The first step of our project will be constructing four 13’ x 150’ caterpillar (mobile, passive solar) tunnels at Missoula Grain and Vegetable Co. (MGVC) for expanded winter production. In 2021, the three stationary high tunnels on the farm were updated with greenhouse ventilation. Peak vents were installed at both ends of the tunnels to provide tunnels with an outlet for moisture. This manually operated vent reduced moisture buildup on row covers with the goal of reducing plant stress and mitigating the impacts of high-moisture environments on crop failure and crop quality. In addition to regulating the ventilation, sensors were installed in three high tunnels and one caterpillar tunnel. These temperature and humidity sensors compiled records that were accessible on smart phone devices via wifi to a data monitoring app. Over the course of the three year study, we tracked temperature and humidity data. And used that information to inform harvesters on the proper times to enter and begin working in tunnels. The impacts of temperature and humidity on crop yield and input costs was outside of our ability to analyze for this study. But based on the data that we were receiving about temperatures under row cover, we were able to make decisions about increasing/decreasing the number of row cover layers in various greenhouses.

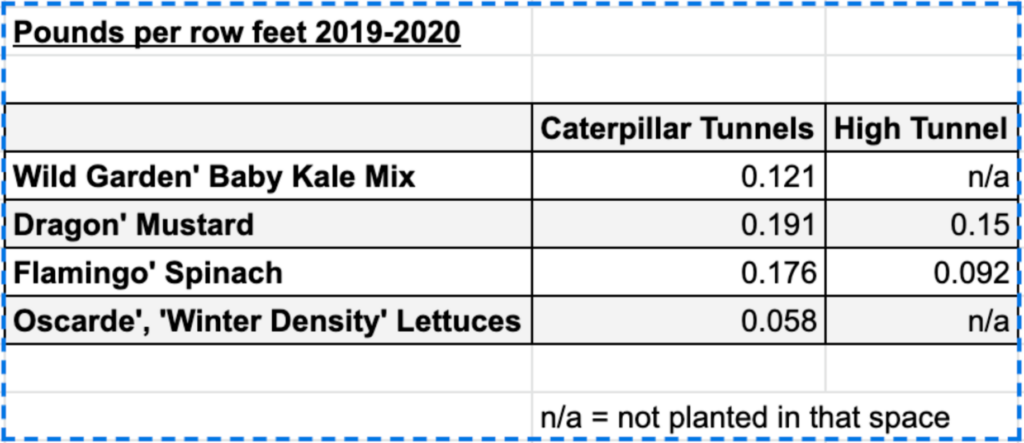

In the winter months of 2019-2020, we trialed cold-hardy varieties of four species of greens including baby kale, spinach, mustard, and lettuces. The crops chosen represent a typical diversified farm production system in order to be relevant to a wide variety of growers in northern climates. Baby Kale and the two lettuce varieties were the only plants we did not trial in both spaces. The three high tunnels and four caterpillar tunnels provided replication for the variety trials under slightly different conditions. Weights of each trial green were harvested. Length and number of rows per harvest sample were recorded. This data was used to extrapolate an average yield per row foot for each green. We mitigated the inevitable variability of fertility between different tunnels by collecting soil samples before planting in fall of 2019. Nitrogen and phosphorus deficiencies we discovered in the caterpillar tunnel soil samples were addressed with 7-12-0 and 13-0-0 fertilizer additions.

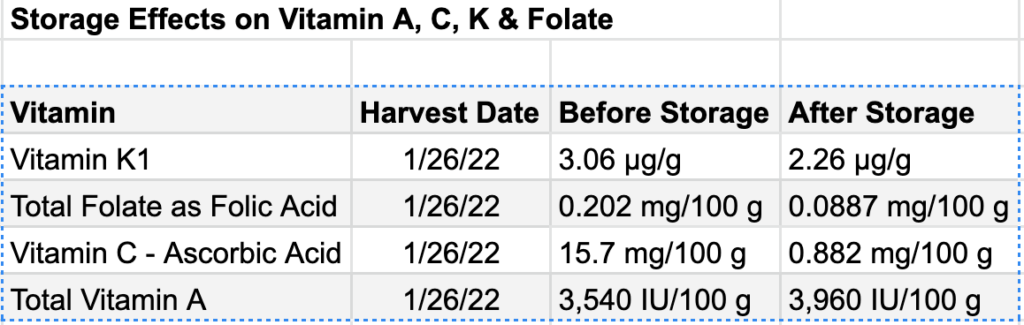

In addition to evaluating growing systems for winter greens, we explored the effects of storage conditions and duration on crop marketability and nutritional value. A temperature and humidity sensor connecting to wireless monitors in the walk in cooler at MGVC kept daily records during the spinach storage experiment. Greens were stored in tight containers that were vented slightly at the base. A hose was used to lightly spray the tops of the greens in these containers before packing into the cooler. This water addition was provided to increase the humidity in the container. Leaf tissue samples from the 'Flamingo' variety of green spinach were sent for analysis to the Eurofins Scientific Inc. labs in Des Moines, Iowa to determine how nutritional value is affected by storage duration. Using commercial food laboratory testing, we looked for differences in the presence of nutrients that change quickly in produce and provide essential health benefits, namely: Vitamin K1, Total Vitamin A, Total Folate as Folic Acid, and Vitamin C.

We used Western SARE surveys in 2022 of students, faculty, and community members at three outreach events to help measure what these different groups were taking from their experience on our "winter farm"-themed tours.

RESULTS:

KEY FINDINGS

Greens Yield Findings

After tracking yield data from multiple high tunnel systems and variety trials, we identified these findings:

- Different structures require slightly different seeding dates for maximum production and minimal crop loss. Seeding in the field and building a temporary caterpillar tunnel allows for earlier seedings (2-3 weeks earlier) because the lower daily temperatures don't create the conditions for quick growth in October and November. By contrast, tunnel seedings need to be delayed so leaves don't get too big and susceptible to hard frosts.

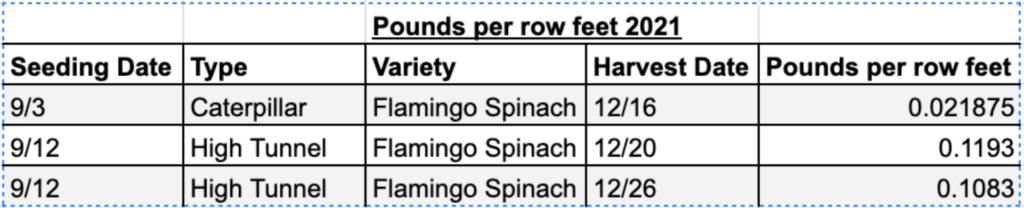

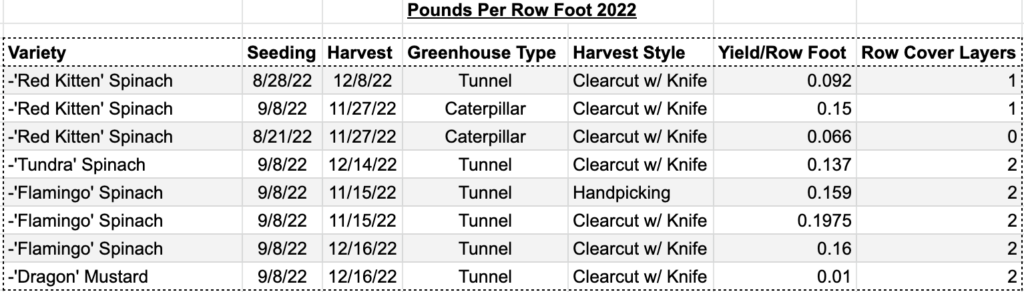

- Some plant species -- mustards, brassicas, and many lettuce -- are too frail for reliable winter production in our climate, regardless of whether they're grown in high tunnels or caterpillars. The results above show that these species yielded well in the first year of the trial. But we had complete crop failures in year two of the study. While we did not record yields that year due to the stress of that experience, they were similar to the harvest yield data recorded for 'Dragon' mustards in 2022. It's not that these plants don't produce food; it's that the time it takes to harvest makes growing and protecting these greens unprofitable compared to other greens like green spinach, red spinach, chard, kale, claytonia. A winter production farm only has so much time to harvest during thawed windows of time. This scarcity informed a study design change between the winters of 2019-2020 and 2021-2022. Our data collection scope shrunk so that we could answer questions related to different spinach varieties seeded at different time periods in these different structures. Mustards grown in both high tunnels and caterpillar tunnels were far less productive than spinach unless these mustards get harvested before single digit outdoor temps (typically before December). We did just that (harvested early in the winter) the first year of the study where high yields were recorded between 0.121 - 0.191 lbs./row ft.

- Comparisons between study years uncovered a surprising similarity between yield of spinach that was seeded too early, got too large, and was minimally protected appeared just as unproductive as highly protected spinach that is eaten by rodents. The yields for these two conditions were 0.06lbs/row ft and 0.02lbs/row ft, respectively.

- Spinach yielded best (.150-.158 pounds per foot) when the following criterion was met:

- seeded at the optimal periods for their given structure type

- exposed to frigid temps when outdoor temps dropped into the teens and single digits under only 1 layer of row cover

- covered with additional row covers as outdoor temps moved into the negative degrees

- minimal/no eating damage from voles, mice, shrews, and pocket gophers

We observed no spinach that needed to be discarded after being stored between 1/26/22 and 3/2/22. It was all deemed high-quality visually after this storage period. There were no signs of yellowing or dehydrations after being held for over a month at 33-38 degree conditions in our farm's walk-in refrigerator. We hypothesize that this was due to the cold temperatures experienced during harvest.

Nutritional Findings After Spinach Storage:

- For future samples, we recommend using NP analytical for nutritional testing. They are willing to measure time-sensitive samples the morning after they're shipped overnight to them.

- Vitamin C and folate dropped significantly which our advisor, Dr. Wan-Yuan Kuo, said was to be expected. She said just 15 days can drop Vitamin C, so the 6 day delay might already drop Vitamin C

- Vitamin A seemed increase slightly (can’t be sure if all data was measured with one replication), which may be due to moisture loss or postharvest biochemical synthesis

- Vitamin K did not seem to drop significantly. And, unlike the other nutrients, the results of Vitamin K did not draw a comment from Dr. Wan-Yuan Kuo.

Technology Findings:

Unpredictable temperature swings can drastically impact crop survival and productivity within winter growing structures and underneath row cover. A weather station and a remote temperature monitoring system with multiple wireless sensors were key in informing decisions and observations throughout this project, and in terms of improving success for winter crop production.

The weather station and sensors informed decisions on:

- Tunnel side venting

- Tunnel peak venting

- Identifying and addressing leak-points on tunnel structures and temperature controlled storage spaces

- Row cover layering, application, and removal

- Optimum temperature alert levels for tunnel structures and temperature controlled storage spaces

Research Outcomes

Education and Outreach

Participation Summary:

In January 2020, we shared about the early results of the research project with the annual Planning for On-Farm Success Workshop hosted at Missoula Extension in January, which had 16 students, 2 extension agents, and several staff members of CFAC participating.

By March 2020, details about the project were shared twice in the farm’s newsletter which reaches over 200 community members in Western Montana, primarily customers and CSA members. At the time of this update, we had also connected with five visitors about the project through tours, two at the farm and three at the research center, and anticipate many more opportunities to share with visitors and volunteers in the years to come. Using data and valuable lessons from the winter season, we have developed a handout to use with visitors and in presentations explaining the variety trials, season extension experiments, and monitoring technology. In 2020, the project was not presented at WARC’s Field Day in July due to a cancellation. We experienced a lull in farm educational activity and many of our aspirations to attend workshops were thwarted by the pandemic.

In August 2020, we held one Field Day at MGVC in collaboration with Missoula Community Food and Agriculture Coalition (CFAC), targeting beginning farmers and freely available to the community. The event was publicized through the NCAT listserv, the CFAC website and newsletter, and the farm newsletter. Due to Covid-19 safety concerns and because part of our workshop featured in-greenhouse and in-packshed demonstrations, we hosted the event virtually. We drew 15 participants to the online. The farmers Katie and Max were filmed in advance of the webinar so that viewers could witness the high tunnels, low tunnels, caterpillar tunnels, as well as the venting and row cover materials utilized in this SARE project. Questions from participants surrounded planting dates, row covering procedures, varietal selection, and harvest weights. Many of these questions were related to the practices and data we've documented through the SARE grant.

On March 11, 2022, we hosted 15 students of the University of Montana Agroecology course. This was at the heels of our winter trials, and we were already turning beds over into new Spring plantings, but we were able to cover many of the storage spinach results that had just come in. As the professor responded through a survey, "I teach a course in Agroecology, and our study of abiotic factors affecting farm ecosystems is really illuminated by Missoula Grain and Vegetable's winter production. I will continue to bring students to the farm to witness plant responses to light and temperature...they’re an amazing case study for students to understand and visualize various aspects of creative field production and business management."

On June 8, 2022, Katie Madden participated in the 2022 Field Tested Tool Expo at the PEAS Farm. She provided a field demonstration of how to use the paperpot transplanter, describing the winter planting context that we utilize at Missoula Grain and Vegetable Co. Katie also provided the roughly 10 producers on-site with an analysis of which greens crops we use the paperpot tool for and which winter crops we no longer plant.

On July 28, 2022, we hosted 8 students of the Townes Harvest Gardens practicum class from Montana State University. Although we were not in "winter mode", we discussed the impact of winter growing on our small farming business and touched a lot on the differences between caterpillar tunnels and high tunnels. Several members of the class completed surveys. And this winter following the completion of the project, several students in the class were forwarded a link to our short video with the key findings. "As an educator, I find examples of real-world application of ag technology and growing methods to be an invaluable asset. Farmers trust each other and appreciate farm-based evidence. Sharing successful farm stories has been an effective tool for spreading new methods and tech in our farming communities."

Finally on September 21, 2022, a group of 25 professionals in Ravalli County (including farmers and other business owners) toured the farm tunnels and our refrigerated facility. They were curious about the storage techniques and they were able to see many of the fall plantings of late August and early September in their seedling stages. Here's what one survey respondent remarked: "Learning about their new winter storage and spinach varieties that lasts a month after harvest led me to research deeper into climate-specific varieties and what chemistry is involved in the difference."

"Western Region Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education Program Outreach Surveys" were used to the best of our abilities at our on-farm events.

These survey responses did not meet our objective to identify additional areas of need. And admittedly we have drawn more interest for our work by sharing winter production strategies, planting dates, and harvest data through online social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook. This seems to be where a sizable cohort of vegetable producers congregate, feel comfortable reaching out, and interacting with stories and posts that we make to peek peoples' interest in winter growing. It's embarrassing to admit that we've been successful at engaging producers like those at Chance Farm in Bozeman, Montana and Mountain Bluebird Farm in Hayden, Colorado on social media. But when we consider the downturn in producer interactions at in-person conferences while Covid-19 safety concerns lingered, it's easier to understand how communication online has been more effective during the years of this project.

Nonetheless, we were able to demonstrate an increase in awareness of our strategies for producing and storing high-value winter greens through these surveys at tours and workshops.

Education and Outreach Outcomes

See Project Outcomes section

Installing and managing frost-protection technology

Improving profit margin with labor efficiencies

Reducing risk of crop failure with climate sensors

Conservation of energy resources for winter production

Identifying more reliable crop varieties