Final report for FW23-427

Project Information

Our specialty crop research project aimed to enhance knowledge about drought-resistant crops and desert plants, as well as mitigate soil erosion and pollution, restore our local ecosystem and regrow our plant and animal pollinator population by restoring one acre with CAM (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism) succulents and other native plants.

The initiative also addressed food insecurity and agrobiodiversity to enhance producer resilience and broaden American food diets with the reintroduction of traditional indigenous and campesino crops native to AridAmerica.

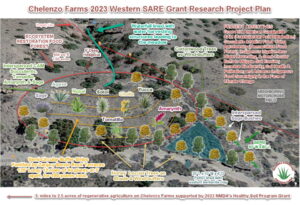

We employed indigenous-inspired and contemporary water harvesting structures, including dams, Zuni bowls, zaja y bordo (Mexican ditch-and-berm) and Keyline structures to promote the understanding and use of irrigation-less agriculture, especially among drought-plagued producers in the Southwest. For the project we used this methodology on two acres of our land, building upon work that had been completed as part of the NMDA’s Healthy Soil Program grant initiative that had been completed the previous year that focused on rejuvenating the health of the soil

Working with our technical adviser, Dr. Sangu Angadi, we researched and discussed implementing Semi-Circular Buffer Strips that employ a half-circle form of crop planning to mitigate soil erosion, harness water, and serve as a wind buffer. Due to the fact that the project plans were to solely depend on water harnessed by monsoon rains, snowmelt and the significant condensation that we anticipated to experience in fall and winter when temperatures warm up by 30-40 degrees on a daily basis, we ultimately did not implement this part of the project due to the record heat in 1993 and the lack of precipitation (i.e. monsoons).

Despite ongoing climate change, drought and record heat waves, this project served as an experimental model and provided baseline data for the expansion of ecological regeneration on 350 acres, which we hope to support by a future ecosystem restoration camp.

We did not proceed with the work we intended to do with local nurseries to develop pipeline because the major nursery that purchased and supplied succulents to Santa Fe and bordering areas closed down after 40 years on May 27, 2023. We ultimately ended up purchasing much of their stock of succulents, which we planted on June 10, 2023. Despite the heatwave, we still have over 300 of the original plants and subsequent pups ("hijuelos") that we are caring for in our nursery. Considering it takes 2-4 years to grow agave seedlings /starts, we will consider building a pipeline for future nurseries down the line, in addition to planting more of the starts that we believe will survive outside.

Despite efforts to reach out to Indigenous & Campesino-related organizations to develop partnerships to promote and enhance the educational component of the project, we have been unable to establish any meaningful partnerships thus far. We had extensive correspondence with a local tribal elementary school, the Keres Children's Learning Center in the Cochiti Pueblo, but our efforts were not fruitful. We will continue to attempt to build partnerships as time, resources and opportunity permit.

Due to necessary shift in project plans due to the continuing heat waves and subsequent demise of much of our planted crops, we decided to hold off on Mezcal educational session addressing sustainable agricultural and environmental issues. As the plants in our nursery mature and we continue to nurse partnerships we will look to organize and host these sessions starting in Fall. Meanwhile, the primary consultant who will execute these sessions, Marsella Macias, continues to offer her services as we nurture the remaining crop of succulents, especially agave. In particular, we are looking to prospectively host educational sessions with our local college, Santa Fe Community College, and their sustainability programs, as Lorenzo serves on the Board of Directors for their Foundation.

Also of note, half of the original project team members left the farm before execution of many of the planned tasks. Thus, due to this significant resource restraint we were quite limited in terms of help and thus modified plans accordingly.

Our Outreach Activities included

- Onsite workshops focused food forest development supported by water harvesting structures and terraces

- Regular blog posts on our and partners’ websites

- Presentation at 2023 the Tucson Agave Festival

- Radio talk show about sustainable agriculture with guests focusing on agave cultivation

- Mezcal and agave educational sessions that address a number of agricultural and environmental issues.

- Address food security and agrobiodiversity to enhance resilience and broaden American food diets by optimizing land management and sustainable production systems with the reintroduction of traditional indigenous and campesino crops native to AridAmerica.

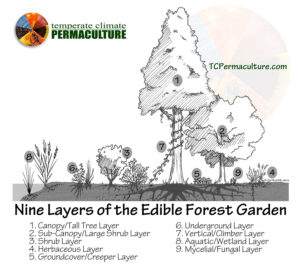

- Conversion of one acre at Waterfall Meadow on Hacienda Dominguez & Chelenzo Farms (Cerrillos, NM) into a permaculture food forest with CAM succulents & native plants found in the Galisteo Basin of New Mexico. This initiative will serve as an experimental model and provide baseline data for expansion of ecosystem restoration on 350 acres, which will be supported by a future ecosystem restoration camp in the neighboring one-acre field.

- Employ indigenous-inspired and water harvesting structures including one-rock dams, Zuni bowls, zaja y bordo (Mexican ditch and berm terraces to support agave) and keyline structures to promote the understanding and use of irrigation-less agriculture, especially among producers in the American Southwest, which has experienced a multi-decade doubt and will likely continue to considering climate change forecasts.

- Working with our technical adviser, Dr. Sangu Angadi, implement Semi-Circular Buffer Strips. Using a media luna (half circle) approach we will use this form of crop planning to mitigate soil erosion, harness water, and serve as a wind buffer (wind combines with precipitation, being the primary cause of soil erosion in the high mountain desert). We will not be using irrigation and solely depending on water harnessed by rain, snowmelt and the significant condensation that we experience in fall and winter in Northern New Mexico when temperatures warm up 30 to 40 degrees on a daily basis.

- Promote awareness about the importance of using native seed and seedlings for ecological system restoration and increase availability of native seed and seedlings for habitat restoration and conservation by establishing a seed bank via a partnership of the Applied Ecology’s Southwest Seed Partnership Program and the development of a starts nursery in our 33’ geodesic grow dome.

- Contribute to the knowledge in specialty crop research focused on drought-resistant crops and desert plants, including ten CAM succulents and native plants highlighted by Gary Paul Nabhan, Patricia Colunga-GarcíaMarín and Daniel Zizumbo-Villarreal in the June 2022 paper “Comparing Wild and Cultivated Food Plant Richness Between the Arid American and the Mesoamerican Centers of Diversity, as Means to Advance Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the Face of Climate Change.”

- Mitigate soil erosion, restore soil health and our local ecosystem, as well as regrow our plant and animal pollinator population.

- Establish and supply existing pipeline for indigenous/ethnic food markets and nurseries for CAM succulent products, especially those serving clients seeking ecological restorative vegetation, which is experiencing a supply shortage.

- Mitigate local pollution caused by carbon monoxide and dust that blows over from the neighboring motocross track by planting Honey Locust trees and shrubs as a windbreak. Parallel to the project meadow is a large berm that was likely created by the Army Corps of Engineers to mitigate flooding from an arroyo that runs perpendicular to the berm to the Santa Fe Railroad line that runs through the Galisteo Basin along the Galisteo River.

|

Timeline |

Activities & Major Milestones |

Team Members |

|

April 2023 |

Water Harvesting Structures Planning |

NL (left farm in Nov 2023) |

|

April 2023 |

Soil sample collection and lab delivery. |

LD |

|

April 2023 |

Presentation of project at Agave Festival |

LD, CH |

|

April 2023 - April 2024 |

Work with local nurseries to develop pipeline. |

LD, CH |

|

April 2023 - April 2024 |

Reach out to Indigenous & Campesino-related organizations to develop partnerships to promote and enhance the educational component of the project. |

LD |

|

May 2023 |

Mezcal educational session addressing sustainable agricultural and environmental issues. |

LD, MM, CH |

|

April 2023 |

Field and Project Preparation for Permaculture Indigenous Food Forest Building Workshops: Building Water Harvesting Structures in Waterfall Arroyo |

LD, JN, MM, CH |

|

April 2023- May 2024 (Once a month) |

Radio talk show about sustainable agave agriculture and Mezcal production and promotion; featuring experts, producers, influencers, leaders and scholars from all affiliated industries |

LD |

|

June 2023 |

Field and Project Preparation for Permaculture Agave & Succulent fields |

LD, JN, MM, CH |

|

April 2023-April 2024 |

Ongoing Development and Maintenance of Agave & Succulent fields |

LD, JN, MM, CH |

|

April 2023-April 2024 |

Ongoing gathering of seeds and development of nursery starts/seedlings in our 33’ geodesic grow dome ecological system and habitat restoration and conservation. |

LD, MM, CH, IAE |

|

July 2023 - September 2023; Summer 2024

|

Participating in local Cerrillos Farmers Market in Cerrillos and The Village GreenGrocer in Madrid showcasing specialty crop products (i.e. "tunas", cactus pears). |

LD, CH, |

|

April 2024 |

One-year progress report will be produced and shared online |

LD |

Team Member Key:

|

Member |

Initial |

|

Lorenzo Dominguez |

LD |

|

Joe Newman (Cactus Rescue Project) |

JN |

|

Marcella Macias |

MM |

|

Chelsea Hollander |

CH |

|

Institute for Applied Ecology |

IAE |

Cooperators

- - Technical Advisor

Research

|

Research Objective |

Time Period |

Project Site |

Innovative Research Design, Methods & Materials |

Data Collection & Analysis Methods |

|

Create a permaculture food forest that will serve as an experimental model for agricultural and ecosystem restoration expansion. |

April 2023 - May 2024 |

One acre at Waterfall Meadow on Hacienda Dominguez & Chelenzo Farms (Cerrillos, NM); Moved to one acre plot known as "Field D," to build upon progress from NMDA Healthy Soil Program work. |

|

|

|

To grow crops without irrigation. |

April 2023 - March 2024 |

Ibid, Field D |

|

|

|

Mitigate soil erosion and restore soil health caused by wind and water and lack of biodiversity. |

April 2023 - March 2024 |

Ibid, Field D |

|

|

|

Improve our local ecosystem, as well as regrow our plant and animal pollinator population. |

April 2023 - March 2024 |

Ibid, Field D |

|

|

|

Although CAM succulents and other native plants may increase producers’ crop yields, there is a small market for these specialty crops. The objective would be to create a market for traditional indigenous and campesino crops native to Arid America. |

Summers 2023-24 |

|

|

|

PLANT INVENTORY

| Scientific Name | Common Name | Type | Products & Uses |

| Agave | Century Plant; Maguey | CAM | Food, beverages, fiber, and supplemental animal fodder. |

| Cylindropuntia | Cholla | CAM | Food |

| Yucca | Yuca | CAM | Food |

| Opuntia ficus-indica | Nopal, Prickly Pear Cactus; the Indian fig opuntia, fig opuntia, barbary fig | CAM | Food; medicinal purposes; flavoring |

| Dasylirion Wheeleri | Desert Spoon | CAM | Alcoholic drink, fiber for goods. |

| Amaranthus | Amaranth | Grain | Food, livestock feed |

| Atriplex halimus | Saltbush; A. hortensis; quailbush | Shrub | Livestock feed, bird shelter, soil protection, medicine; leaves and seeds eaten |

| Physalis | Tomatillo; Gooseberry; Goldenberry; aguaymanto, uvilla, uchuva | Fruiting plant | Fruit, jams, jellies, sauces. |

| Salvia` | Sage | Shrub | Psychoactive properties |

| Populus | Cottonwood | Tree | Lumber |

| Gleditsia triacanthos | Honey Locust | Tree | Pollinator, nitrogen-fixer, shade, livestock fodder, insect nectar, high quality lumber. |

Research Citations

Comparing Wild and Cultivated Food Plant Richness Between the Arid American and the Mesoamerican Centers of Diversity, as Means to Advance Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the Face of Climate Change. by Gary Paul Nabhan, Patricia Colunga-GarcíaMarín and Daniel Zizumbo-Villarreal, Front. Sustain. Food Syst., Sec. Crop Biology and Sustainability, June 2022.

Agave as a model CAM crop system for a warming and drying world, by J. Ryan Stewart, Frontiers in Plant Science, September 24, 2015.

Agave Power: Greening the Desert, by Ronnie Cummins, Regeneration International, December 22, 2020.

Expanded Potential Growing Region and Yield Increase for Agave americana with Future Climate, by Sarah C. Davis, John T. Abatzoglou, and David S. LeBauer, Agronomy: Simulating the Impacts of Climate Change on Hydrology and Crop Production, October 21, 2021.

Productivity and water use efficiency of Agave americana in the first field trial as bioenergy feedstock on arid lands, by Sarah C. Davis, Emily R. Kuzmick, Nicholas Niechayev, Douglas J. Hunsaker, GCB-Bioenergy, December 19, 2015

Agave Cultivation, Terracing, and Conservation in Mexico, by Matthew LaFevor, Jordan Cissell and James Misfeldt, Department of Geography, University of Alabama, Focus on Geography.org

What’s Going On in This Graph? | Growing Zones: How are the growing zones in the United States shifting, and how do these changes affect which plants can grow successfully by region? New York Times, April 8, 2021

After conversations with a permaculture and an agave specialist, as well as record-high summer temperatures over the summer of 2023 and no precipitation during our usual monsoon season of July and August that year, we decided to change the original plans for the project. Instead of creating a field of succulents with other native plants that was located a quarter of a mile from our primary operation and any source of supplemental water (if nature did not supply any), we decided to modify our plans by planting in an acre where we had already done substantial conservation work with the building of water harvesting earthworks and the regeneration of the soil through a preceding soil health rejuvenation project.

In addition to the limits that our natural resources presented for this project, in the process we discovered that the original field destined for project implementation had an extraordinary amount of "soil crusts" (aka cryptobiotic, cryptogamic, or microbiotic crusts), which are living soil crusts that form when cyanobacteria, algae, fungi, lichens, and bryophytes colonize the surface layer of arid soils. As a result, we were advised not to disturb such a delicate desert landscape.

According to Steven D. Warren of the U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Shrub Sciences Laboratory, "Biological soil crusts...are common in most deserts and perform functions of primary productivity, nitrogen fixation, nutrient cycling, water redistribution, and soil stabilization. The crusts are highly susceptible to disturbance. When disturbed, biological soil crusts lose their capacity to perform their ecological functions. Natural recovery of disturbed crusts can range from several years to millennia... Intense and/or repeated disturbance may eliminate crust organisms and diminish carbon inputs into the system (Kasper, 1994; Johansen et al., 1998). In harsh environments, reductions may last half a century or more." (Source: Role of biological soil crusts in desert hydrology and geomorphology: Implications for military training operations, The Geological Society of America Reviews in Engineering Geology XXII 2014).

Moreover we experienced an unexpected resignation of one of our key contributors to the project, our farm manager who was tasked with a major portion of project implementation. Without her help, it became increasingly difficult to devote time and resources, when other farm activities and initiatives were more pressing.

Thus, our project plans were shifted to "Field D," a one-acre plot that is one of four fields (Fields A-D), which are part of a project that is supported by New Mexico Department of Agriculture's Healthy Soil Program. The dryland farming project began September 23, 2022 with the creation of terraces supported by water harvesting earthworks where we eventually planted agave. With the objective of regenerating the health of the soil on an arid parcel that had approximately 15% vegetation, on the terraces of Fields C & D we spread compost, cover crop seed (winter wheat, winter rye, hairy vetch and fava bean), and hay as mulch to retain moisture. We also placed juniper branches atop the mulch to prevent the wind from sweeping away the straw. Miraculously, nature complied and two weeks later we had four days of rain in early October, which led to a significant growth of cover crops on these terraces.

On June 10, 2023, we hosted a workshop with two dozen volunteers that helped us plant five types of 400 succulents with multiple varieties of each (# indicated in parentheses). These included Agave (21), Cholla (2), Dasylirion (3), Opuntia/Cactus (2), and Yucca (9). There were 200 plants, 40 of each type planted in Field A, and 260 Agave planted in Field D.

Due to our limited resources, primarily labor, our plan was to water the newly planted seedlings once a week. However, the worldwide record high temperatures of July hit and we watered the plants twice a week, but this was not enough to sustain the plants and ultimately nearly half did not survive.

On December 17, 2023 we conducted an inventory of the agave in Fields A & D with the following tabulation:

| Location in Field D | Alive | % | Dead | % | Total Agave |

| Top Terrace | 48 | 82.8% | 10 | 17.2% | 58 |

| Mid Terrace | 27 | 81.8% | 6 | 18.2% | 33 |

| Gulley to Lowest Terrace | 27 | 42.9% | 36 | 57.1% | 63 |

| East Terrace & Road | 29 | 28.7% | 72 | 71.3% | 101 |

| Field A | 26 | 72.2% | 10 | 27.8% | 36 |

| TOTALS | 157 | 54.0% | 134 | 46.0% | 291 |

We observed that there was a high rate of survival and that the plants seem fairly thriving (solid green pencas, the agave leaves) on the top and mid terraces of Field D, which are as a greater slope and more sand, rock and clay. We had observed similar conditions for agave in the Gila Forest of New Mexico on a foraging trip in 2022. As agave needs to have well draining soil, this correlates well with why those placed higher on the field did better.

We covered those agave that had survived with landscaping fabric to protect them against the frost and expected snowfall this winter. During the first week of March we uncovered all the plants with a forecast of above 33 degrees for most of March and some much needed precipitation. We found that almost all survived, but some of the bottom run pencas had either browned considerably or died. Apart from frost, we suspect that since we used dark landscape cloth to cover the plants, the lack of sunlight may have contributed to their partial withering as well.

Most of the cholla and cactus have survived, as most were native species. However, we have observed that much of the cactus, where planted or already existing have large portions eaten from the pads, presumably by wildlife in need of some succulent nourishment (and a source of water). None of the agave show any signs of being eaten by wildlife.

As a result of our research thus far, where climate change and drought remain significant factors in sustainable agriculture we recommend growing agave and other succulents indoors, in greenhouses or high tunnels, for a few years prior to planting outside in order to increase the plants' rate of survival. The need for patience when it comes to planting alternative drought resistant crops like succulents presents an inherent conundrum, especially considering that market forces and financial farm sustainability often press for more immediate results.

That said, patience is a virtue. Allowing and supporting growth can reap many benefits, considering the prospective multiple uses of agave and other succulents. These include the production of human food sources, such as cactus fruits and pads and agave hearts for specialty ethnic markets; fermented livestock feed; biofuel; fiber for household products; use for forest fire lines; encouragement of water conservation through the propagation of commercial and residential xeric gardens; distillate products such as tequila, mezcal and sotol; ecosystem restoration through the increase of pollinators and residual wildlife.

We also inventoried a few hundred agave seedlings that we keep in our makeshift nursery (a 10 x 12 insulated shack), and found that 75% had survived thus far this year. Rather than risk losing a significant portion of our crops, we plan on delaying the planting these in the fall of 2024, after the extraordinary heat anticipated again this summer. At this time, we are also planning to plant the other native plants that were part of the original planting plan on the cover-cropped terraces. These include amaranth, saltbush, tomatillo, and sage bush. We have already planted tomatillo starts in our greenhouse, and may plant a portion earlier in our drip irrigated gardens, rather than risk their demise as part of our dryland farming project.

The planting of 60 cottonwood tree seedlings acquired from the US Forest Service and honey locust tree seeds (collected locally) were also part of the original plan, and were planted in May of 2023 in the original planned area. However, due to the unforgiving lack of precipitation in 2023, all have died. As a substitute, we have acquired mesquite trees, which we pan on integrating in Field D and which are being used as nitrogen fixers, specifically coupled with agave planting as part of the Billion Agave project, which is a "ecosystem-regeneration strategy recently adopted by several innovative Mexican farms in the high-desert region of Guanajuato." (https://regenerationinternational.org/billion-agave-project)

We also plan to continue expanding our building of water harvesting earthworks (one rock dams, zuni bowls, check dams, etc.) as an extension to the east of Field D and are considering building retention ponds with the clay purchased that was intended to be used for the retention pond in the original area of the project.

We have worked closely with one of our advisers, Marsella Macias, a graduate student at UNM who is working on cultivating agave.

We are also looking to partner with other organizations, so that we may offer the planned mezcal education sessions, to be led by Ms. Macias. This includes the Santa Fe Community College Foundation Board of Governance, which Lorenzo is a member of. He is working directly with the Executive Director to prospectively plan mezcal/agave education sessions with community leaders.

Being that we have moved the project from the original intended "waterfall meadow" to Field D, the plans to implement semi-circular buffer strips no longer are relevant or apply. That said, the purpose of the semi-circular buffer strips was to help diminish wind soil erosion and to offer protection to our planted succulents and native crops. This remains an issue in Field D, which we hope to mitigate with the planting of buckwheat on the terraces between the rows of agave plantings, where we previously successfully planted cover crops. This planting may not take place until after July however, to avoid the anticipated intense heat, but the 10-12 week growth period would synchronize well with establishment period of agave seedlings that we intend to prospectively plant in August. There is a possibility that we may choose to wait another year, to sustain further growth and strength from our agaves that have kept in our greenhouse.

During the project period we continued to build out indigenous-inspired and contemporary water harvesting structures. In general, these structures all served similar purposes - to either down water from rainfall and collect sediment, as well as to spread water away from naturally occuring arroyos (gullies) and in turn minimize soil erosion. The one-rock dams (named so because they are only one rock high) are used to slow down water flow in gullies; Zuni bowls also slow down water, but also collect the water in its bowl shape; the zanja y bordo (Mexican ditch-and-berm) have the berm on the down-hill side of the berm, so that succulents can be well-draining to prevent rot-rot; and Keyline structures work with the contour of the land in order to convey and stay water.

Research outcomes

Education and Outreach

Participation summary:

At the start of the project, Lorenzo attended the Agave Heritage Festival and spoke on a panel about sustainability and agave farming. There were approximately a dozen audience members. Thus, we've concluded that education and outreach can be difficult because interest is currently limited with the general population and prospective producers who must focus and be concerned about short-term returns on investment. Although the Agave Heritage Festival is seemingly the optimal venue for education and outreach, many of the attendees attend for the opportunity to drink agave spirits.

As a result, we decided to forgo attending the Agave Heritage Festival in April of 2024, with hopes that we will have more to report by 2025.

I've also spoken about agave growing as part of my radio show, El Puente, on KSWV radio in Santa Fe, when I hosted Dr. Ben Wilder on June 3, 2023.

Dr. Ben Wilder, a botanist, desert ecologist, and biogeographer, earned his doctorate in botany and plant sciences in 2014 from the University of California, Riverside and has a bachelors of science from the University of Arizona in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. In 2011 he co-Founded the Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers, and currently serves as the organization's director. He has served as Director of the Desert Laboratory on Tumamoc Hill with the University of Arizona from 2016–2022 where his relationship with agave really flourished. He has served as Director and coordinator of the Consortium for Arizona-Mexico Arid Environments and was a Visiting Scholar at Stanford. He has spent much of his career researching desert plants in Mexico, especially the Gulf of California. He's been the recipient of over 60 fellowships, awards and research grants over the last twenty years and has written more than 30 peer reviewed papers, a book, and book chapters.

During our discussion we talked about the importance of cultivating agave and why growing it here in Northern New Mexico, as we are pioneering at Chelenzo Farms, will be how we help mitigate climate change and do our part to save the world.

In July 2023, our efforts were featured in "Regenerating New Mexico," an amazing project being implemented by Ecotone Landscape Planning, LLC , High Watermark LLC and the NM Healthy Soil Working Group.

From 2024-2026, Lorenzo will also serve as the "voice" of regenerative agriculture in both English and Spanish for a 2501 project grant received by the Quivira Coalition. The project includes the development of 24 radio segments that will focus on promoting regenerative agriculture to producers throughout New Mexico. As part of the content development team, he also intends to suggest the inclusion of agave farming as a viable answer to developing drought resistant crops and strategies.

In September of 2023, Lorenzo penned an article for the Green Fire Times that was published in its September/October issue. The article was entitled "Dueling with Drought: How Regenerative Agriculture, Dryland Farming and Water Conservation Can Help Save Farming in the Southwest," and included highlights of our succulent planting, including photos. ( https://www.chelenzofarms.com/el-cafecito/2023-09-09-dueling-with-drought-green-fire-times ).

On September 23, 2023, Lorenzo spoke at the Albuquerque Prickly Pear Festival regarding grant writing methods related to supporting agave, cactus and other succulent growing projects.

In addition, to the positive publicity we have had for our efforts, we have cultivated understanding and disciples of our farm's mission and its cultivation of succulents and promotion of dryland farming via our farm interns. We host interns on a regular basis through the WWOOF (Worldwide Opportunities in Organic Farming) program and all of them learn about and participate in these efforts.

In March 2024, we were asked to partner with Cruces Creatives out of Las Cruces, NM to help support the local sourcing of cactus pads, which will be freeze-dried and sold as "nopal chips." Our task is to find a variety of cactus that is both edible and sustainable in Northern New Mexico and to ultimately grow them and serve as one of the suppliers for this enterprise. Currently, the variety of cactus used grows best in USDA Hardiness Zones 9-12, whereas we lie on the cusp of 7A-7B. Hence, our search for the right cactus continues on. Should we succeed, we believe that this will allow us to further promote our research and education efforts with succulents as viable drought-resistant crops in the Southwest and other arid areas worldwide.

Since the presentations at conferences and on the radio had no measurable way of determining the the impact of outreach, we do not have any quantitative findings to share.

Qualitatively speaking, our efforts continue to be recognized and endow confidence that the publicity has has motivated audiences and readers to consider similar efforts.

Education and Outreach Outcomes

Considering that we are in the very early stages of developing succulents as an agricultural product in the United States, we would recommend patience and low expectations of this infant industry. Currently, much of the fascination with agave and other succulents is focused on the production of distilled spirits. There is a burgeoning group of agave producers particularly in California, but there are very few to none in other Southwest states, we are likely the only agave farmer in the state of New Mexico to our knowledge. Certainly, there are nurseries that cater to private residents and gardeners, but to our knowledge no other farmer is attempting to grow using dryland farming methods.

Thus, we believe education and outreach will be a gradual process, especially considering that plant growth occurs over years and therefore results are not immediately visible and an agricultural product is not marketable for years as the plant matures over time.

Understanding of how succulents can help mitigate climate change.