Final report for GNC16-221

Project Information

Strong Demanding for Organic Food Vs. Low Adoption of Organic Farming

International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) described the United States as the most vigorous organic market (Yussefi & Willer, 2003). Data from the Organic Trade Association shows the U.S. had a continuous growth in organic food sales in the past more than two decades. The annual growth rates ranged between 10% and 20% from 1990 to 2016. Organic food sales accounted for 5.5% of total U.S. food sales in 2016. However, compared with the organic food market demanding and market share, the adoption of organic farming in the U.S. remains at a low level (see Figure 1.). Based on data from USDA NASS (2017), only 0.5% of the U.S.’ farmland is under certified organic operation. The adoption rates of organic grains are even lower. Organic corn acreage represents only 0.24% of the nation’s total corn acreage; organic soybeans acreage is 0.16% of the total soybeans acreage.

Undersupply of Organic Grains and Limited Organic Benefits

The low adoption of organic grain farming among American farmers led to recurring shortages of organic grain in the U.S. Due to insufficient supply of organic ingredients, organic food processors had to cut their product lines (Roseboro, 2016). Organic livestock farmers indicated the availability and affordability of organic feed were the biggest challenges they met (Digiacomo & King, 2015). Under-supply and lacking access to organic feed became the barriers for conventional livestock producers to get into the organic sector, and a causal factor that organic livestock producers deregister from organic certification (Sierra, Klonsky, Strochlic, Brodt, & Molinar, 2008). On the other hand, the low adoption of organic grain farming restricted organic agriculture’s positive environmental impacts on soil and water (Cambardella, Delate, & Jaynes, 2015), and limited its benefits to the rural development (Marasteanu & Jaenicke, 2018).

Need for the Study and Research Questions

Organic livestock producers, food processors, and consumers together made a strong call to increase the adoption of organic grain farming in the U.S. (Alonzo, 2016; Doering, 2015; Roseboro, 2016). However, organic grain farming adoption requires farmers to make systemic changes in their operation; farmers need to learn different farming techniques including cultivation, rotations, biological control, and exploring new markets. Faced with the multifaceted challenges, farmers’ decisions of adopting organic grain farming become intricate. The USDA encourages land-grant universities and agricultural organizations to develop and deliver extension education and research programs to promote organic farming and solve issues related to organic agriculture issues. In this context, with the mission of promoting organic grain farming and facilitating farmers’ organic farming conversion, organic specialists and extension educators need to understand: 1) farmers’ motivations for adopting organic grain farming; 2) challenges impede farmers’ adoption in organic grain farming; 3) feasible strategies to overcome the challenges, 4) beneficial outcomes of organic grain farming, and 5) farmers’ needs of education on organic grain farming.

Though past studies may shed some light on these topics of information (Constance & Choi, 2010; Duram, 1999; 2000, Mccann et al., 1997; Middendorf, 2007; Stock, 2007, Stofferahn, 2009), their studies did not specifically focus on grain farmers, and most of their sampled farmers are horticulture crop and livestock producers. Given the large differences in management and operation between the different commodity types, farmers’ motivations and challenges of organic grain farming adoption may be very different from horticulture crop and livestock operation. Research specifically focused on grain farmers in the U.S. is limited and tends to become outdated (Lockeretz & Madden, 1987; Wernick & Lockertz, 1977). This study aims to answer the following research questions:

1) What are the factors that motivate farmers to adopt organic grain farming?

2) What are the challenges impeding farmers’ adoption of organic grain farming?

3) What are the strategies farmers employ to overcome challenges to organic grain farming?

4) What are the benefits experienced in organic grain farming adoption?

5) What are the farmers’ needs for extension and education regarding organic grain farming?

This research project will enrich and update the body of knowledge on understanding farmers’ organic grain farming adoption in the U.S.

Methods

This research utilized social science methodology with a mixed-method research design. The first phase of this study is a qualitative study through semi-structured in-depth interviews with 18 organic farmers in the state of Iowa. The purpose of interviewers is to gain a deep understanding of why farmers adopted organic grain farming and the holistic process of their adoption of organic grain farming. After analyzed the interview, we developed an instrument based on the findings of the interview. In the quantitative study stage. We sent surveys to all organic farmers who have organic grain operation in the state of Iowa. We received 258 completed surveys. Statistical analysis was conducted on the returned surveys.

Main Findings

Through both interviews and surveys with organic farmers, we found the motivations of organic grain farming adoption include health concern, values on biodiversity, conservation tradition, soil improvement, farm viability, self-challenge, and nostalgia for the old-way farming. The main challenges farmers faced include weed control, time stress, intensive labor and management, machinery, transitional crops marketing, and financial risk during the transitional period. To confront the multiple challenges, farmers have employed different sets of strategies to overcome the challenges which include operational strategies, learning strategies, and financial strategies. Farmers have experienced both economic and non-economic benefits after adopt organic grain farming. The economic benefits include profitability, farm viability, and competing yields. Non-economic benefits include agroecology, enjoyments, human health, and ideological validation. In terms of needs for extension education, organic grain farmers hope to have more programs related to on-farm research, young farmers' education, broader population outreach, and more off-season learning activities. Farmers perceive field day and one-on-one mentorship as effective education formats. The topics they need for more education are weed management, crop rotation, marketing, soil biology, and cover crop management.

Project Outcomes

By sharing this project’s findings with extension educators and organic specialists at multiple conferences and organizations’ meetings. This research project helped extension educators, farmers’ organic specialists and to gain a better understanding of farmers’ comprehensive adoption process of organic grain farming, including motivations, challenges, strategies, benefits, and needs for programs.

References

Alonzo, A. (2016). Infographic: Feed shortage limits organic poultry sector growth. WATT PoultryUSA. Retrieved from https://www.wattagnet.com/articles/25882-organic-poultry-production-growth-hurt-by-feed-shortages

Cambardella, C. A., Delate, K., & Jaynes, D. B. (2015). Water quality in organic systems. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 4(3), 60. doi:10.5539/sar.v4n3p60

Constance, D. H., & Choi, J. Y. (2010). Overcoming the barriers to organic adoption in the United States: A look at pragmatic conventional producers in Texas. Sustainability, 2(1), 163-188. doi: 10.3390/su2010163

DiGiacomo, G., & King, R. P. (2015). Making the transition to organic: Ten farm profiles. (Report No. 207981). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Doering, C. (2015). Organic farmers face growing pains as demand outpaces supply. USATODAY. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2015/08/05/organic-farmers-face-growing-pains-demand-outpaces-supply/31116235/

Duram, L. A. (1999). Factors in organic farmers' decision making: Diversity, challenge, and obstacles. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 14(1), 2-10. doi: 10.1017/S0889189300007955

Duram, L. A. (2000). Agents' perceptions of structure: How Illinois organic farmers view political, economic, social, and ecological factors. Agriculture and Human Values, 17(1), 35-48. doi: 10.1023/A:1007632810301

Lockeretz, W., & Madden, P. (1987). Midwestern organic farming: A ten-year follow-up. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 2(2), 57-63. doi: 10.1017/S0889189300001582

Marasteanu, I. J., & Jaenicke, E. C. (2018). Economic impact of organic agriculture hotspots in the United States. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 1-22. doi: 10.1017/S1742170518000066

McCann, E., Sullivan, S., Erickson, D., & De Young, R. (1997). Environmental awareness, economic orientation, and farming practices: a comparison of organic and conventional farmers. Environmental Management, 21(5), 747-758. doi: 10.1007/s002679900064

Middendorf, G. (2007). Challenges and information needs of organic growers and retailers. Journal of Extension, 45(4), Article 4FEA7. Available at https://www.joe.org/joe/2007august/a7.php

Roseboro, K. (2016). Multiple efforts underway to increase U.S. organic farm land. The Organic and Non-GMO Report. Retrieved from http://non-gmoreport.com/articles/multiple-efforts-underway-to-increase-u-s-organic-farm-land/

Sierra, L., Klonsky, K., Strochlic, R., Brodt, S., & Molinar, R. (2008). Factors associated with deregistration among organic farmers in California. Davis, CA: California Institute for Rural Studies.

Stock, P. V. (2007). ‘Good farmers’ as reflexive producers: An examination of family organic farmers in the US Midwest. Sociologia Ruralis, 47(2), 83-102. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2007.00429.x

Stofferahn, C. W. (2009). Personal, farm and value orientations in conversion to organic farming. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 33(8), 862-884. doi: 10.1080/10440040903303595

USDA NASS. (2017). USDA certified organic survey 2016 summary. Retrieved from https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/zg64tk92g/70795b52w/4m90dz33q/OrganicProduction-09-20-2017_correction.pdf

Wernick, S., & Lockeretz, W. (1977). Motivations and practices of organic farmers. Compost Science, 18(6), 20–24.

Yussefi, M., & Willer, H. (2003). The world of organic agriculture 2003: Statistics and future prospects. Retrieved from http://orgprints.org/13883/1/willer-yussefi-2003-world-of-organic.pdf

The overall objective of this dissertation research project was to increase the understanding of farmers’ adoption decisions and the adoption process of organic grain farming to the body of knowledge. The specific research objectives are:

- Identify the factors motivating farmers’ decisions on adopting organic grain farming.

- Identify the challenges impeding farmers’ adoption of organic grain farming.

- Identify strategies farmers employed to overcome the challenges of adopting organic grain farming.

- Explore the benefits of organic grain farming that farmers have experienced.

- Explore the educational approaches and resources that farmers sought as they considered organic grain farming adoption.

- Develop a framework that illustrates how farmers’ motivating factors, challenges, strategies, benefits, and education affect the adoption process of farmers' organic grain farming.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator)

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator)

Research

Study Area

The U.S. has diverse growing conditions, and it is necessary to study organic adoption in a homogenous area (Duram, 1999; Lockeretz, 1997). We chose the state of Iowa because Iowa is a leading state for grain production. Iowa has the largest production acreage for both corn and soybeans in the U.S. To increase organic grain farming, Iowa is supposed to be the frontline. However, similar to the nation’s situation, the adoption rate of organic farming is rather low. In 2017, there were only 758 certified organic farms in Iowa, comparing to a total of 86,900 farms in the state (USDA NASS, 2019). In Iowa, organic corn accounts for 0.21% of total corn production and organic soybeans represent 0.22% of the total soybeans production (USDA NASS 2017; 2018). The average size of Iowan organic farms also tends to be smaller than conventional farms. The average size of organic farms is 141 acres whereas the average size of Iowan farms is 355 acres (USDA NASS 2017; 2019).

Research Design

To achieve the research objectives, this project employed a mixed-method research design- Sequential Explanatory Design. Phase I: a qualitative study. Phase II: a quantitative study.

Phase I: A qualitative study

To answer our research question in greater depth and given the exploratory nature of this study, we chose a qualitative research design (Creswell, 2014). Qualitative research brings a new point of reference to existing assumptions and helps explain the “real world” (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Qualitative data were collected through on-farm in-depth interviews from November 2017 to March 2018. An interview protocol was developed based on previous organic adoption research literature. A panel of experts, including an organic agronomist, two rural sociologists, and agricultural extension educators, have carefully reviewed the protocol and make revisions with their expertise. The finalized interview protocol is built with ten major questions. Under each major question, probes and sub-questions were given based on the respondent’s answer to the major question. Eight major questions cover:

- Organic farming motivation.

- Personal beliefs related to the adoption of organic farming.

- Barriers, challenges, and difficulties of organic farming adoption.

- Strategies used to overcome the challenges and difficulties of organic grain farming.

- Governmental programs supporting organic conversion.

- Benefits of organic farming.

- Educational programs for organic farming.

- Educational needs for organic farming.

We employed both purposive and snowball sampling techniques. The initial interviewees were recruited by using the listservs of the Iowa Organic Association and the Practical Farmers of Iowa. We selected farmers who have organic grain operations. The subsequent participants were recommended by the precedent interview participants and selected for increasing potential diverse perspectives based on age, farm size, and locations. This purposive selection process allowed us to get a broader range of interviewee’s perspectives without sacrificing in-depth insights.

We conducted 18 semi-structured interviews (Figure 2 presents the interview locations). The interviewees include 16 male farmers, 1 female farmer, and 1 female landowner. The interviewees’ age ranges from 35 or younger to 65 or older. Most interviewees hold a college degree. Fourteen farmers already acquired organic certification, and three farmers were in the transitional organic period at the time we conducted the interviews. Four farmers chose to be interviewed with their spouses, and one farmer chose to be interviewed with his father. The total number of participants in the interview is 23. Interviews started after the participants signed a consent form approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at Iowa State University. On average, each interview lasted about 75 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

We employed a systematic analytical approach following the method-merits of Corbin and Strauss (2008) and Miles, Huberman, and Saldana (2014). The first cycle coding was an open coding process with constant comparisons; the second cycle coding was an axial coding process that explored the relationships between codes and categorized the codes into themes and sub-themes; final cycle coding is selective coding process that unified central themes that answer our research question (Miles et al., 2014). We performed both deductive coding and inductive coding, as suggested by Corbin and Strauss (2008). To enhance the reliability of this study, themes were coded upon an agreement between two coders (Prokopy, 2011). To further establish the validity of this qualitative study, we presented the preliminary coding structure at local organic farmers’ meetings and collected feedback from the audiences (Prokopy, 2011). To protect participants’ personal information, all farmers’ names were coded into two-digit IDs.

Phase II: A quantitative study

In Phase II, generalizable conclusions can be drawn from the quantitative survey’s results. A survey instrument was developed based on the findings of the qualitative study. The survey instrument is divided into seven sections. Section one focuses on motivating factors to adopt organic farming containing twenty-one items. Farmers were asked to rate their level of agreement with each item on a five-point Likert-scale. Section two measures the level of 28-item challenges associated with organic farming on a five-point Likert-scale. Section three includes a list of 34 strategies that can be used to overcome the barriers and challenges of organic farming. Farmers were asked to indicate whether they employ each strategy for their farm operation and rate the level of importance. Section four measures farmers’ perceived level of benefits of organic farming with 15 items. Section five measures farmers’ need for educational and technical assistance programs (15 items). Section seven measures farmers’ demographics and farm characteristics.

To get representative respondents, we sent the surveys to all organic farmers (n=655) who have organic grain operation in the state of Iowa based on the 2019 USDA Organic Integrity Database. We received 258 completed surveys which resulted in a 39.4% response rate. Both univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were conducted on the received surveys.

References

Duram, L. A. (1999). Factors in organic farmers' decision making: Diversity, challenge, and obstacles. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 14(1), 2-10. doi: 10.1017/S0889189300007955

Lockeretz, W., & Madden, P. (1987). Midwestern organic farming: A ten-year follow-up. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 2(2), 57-63. doi: 10.1017/S0889189300001582

USDA NASS. 2017. USDA certified organic survey 2016 summary. Retrieved from https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/zg64tk92g/70795b52w/4m90dz33q/OrganicProduction-09-20-2017_correction.pdf

USDA NASS. 2019. 2017 census of agriculture United States summary and state data. Retrieved from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_US/usv1.pdf

USDA NASS. 2018. Iowa Ag News –2017 crop production. Retrieved from https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Iowa/Publications/Crop_Report/2018/IA_Crop_Production_Annual_01_18.pdf

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Prokopy, L. S. (2011). Agricultural human dimensions research: The role of qualitative research methods. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 66(1), 9A-12A. doi: 10.2489/jswc.66.1.9A

Factors Motivating Farmers to Adopt Organic Grain Farming

Economic drivers (14 farmers)

For most American farmers, farming is an enterprise. Farmers consider economic factors when they make farming decisions, and organic agriculture is no exception. The interview revealed two perspectives of economic drivers.

- Profitability (8 farmers). By having the price premium, organic grain farming can bring better profitability to farmers than the conventional counterpart. The price premium has attracted 7 farmers to adopt organic grain farming in the interview. For instance, farmer #12 said: “I think I heard about those $21 beans per bushel, at that time you could get $21 a Bushel! And I thought, man maybe I should do that.”

- Small farm viability (9 farmers). Organic farmers averagely operate a smaller farm than conventional farmers. For being as small farms, coupling with the sluggish conventional grain markets in the past several years, the farmers are in a disadvantageous position to compete with bigger farmers. Farmer #17 said: “I transitioned because we have a small farm and the goal was to make more money per acre so we could stay on our small farm. Rent is very competitive in this area…Well, I got tired of all the games that the chemical companies played. They were giving special prices to big farmers. They had some people that got way better, cheaper prices than we did, we were small.”

Health concern (15 farmers)

In the interview, we found fifteen farmers put health concern as their motivation to adopt organic farming. Specifically, two perspectives of health concern were discovered by the interview.

- Personal health concern (13 farmers). Thirteen farmers, in the interview, indicated they are concerned about health problems of themselves or their families caused by chemicals when they had conventional farming operations. Farmer #10 explained how his health concern motivated him to adopt organic farming: “There are several reasons why I started organic farming, and the first one is my father got Parkinson's disease, and he later died of Parkinson's disease. And… there is a direct link between those agricultural insecticides and pesticides and development of Parkinson's disease…. So that was a motivating factor.”

- Public’s health concern (4 farmers). After farmers conceived concerns about personal health, some farmers made further reflection and developed a general health concern for the public. Farmer #07 said: “And of course the more you think about it, the more [you concern]. If there's a little bit of residue from a lot of products, it seems like that could have compounding affects negatively on people's health and just seems like we have such a growing problem as far as cancer. You have to wonder what the sources for these things are? How much has it been because of the way food is produced? And, yeah, the side effects and unintended consequences [were there].”

Improvement of natural resources (12 farmers)

Twelve interviewed organic farmers believe their operation should focus on soil health. Organic farmers do not see necessary conflicts between pursuing profitability and preserving natural resources. On the contrary, they believe their farm’s prosperity relies on the improvements of the soil. Farmer #02 identified himself as “a firm believer of soil health,” and he said: “You gotta take care of your soil health and it can be done.” Farmer #14 also said: “I think, maximizing our profit while preserving our natural resources, our soil and so. So those two go hand in hand… Your soil life, your biology in the soil can affect your fertility.” In addition, some organic farmers indicated they have hilly ground, and they found their land had become seriously eroded from the past conventional operations. They chose the organic operation to control erosion and improve the soil. Farmer #05 said, “I thought the soil had been eroding from that top ground to the bottom ground way too much. There was an incentive there to put in oats the first year and we're going to stop some of that erosion…So, not only am I thinking about, oh, raising organic grain and getting a good price for it, but I'm also thinking about what it's doing for the soil.”

Values on biodiversity (7 farmers)

Seven farmers indicated they choose organic farming because it is compatible with their values on biodiversity. Organic farmers believe more biodiversity will bring better ecosystem services and can solve many agronomic problems. Farmer #16 said: “So we see our health and our economy supported by biological diversity and that's very compatible with our quality of life….We believe that biological diversity really is the answer to our problems and that diversity will give us the process.” Farmer #01 further explained: “There's a great number of natural predatorial insects that will eat aphids. That will eat some of the nematodes in the soil. There are natural ways to combat the problems that all farmers have.”

Conservation tradition (6 farmers)

Many of the farmers had adopted conservational practices before they started organic farming.

Six farmers deemed land stewardship as their family farm’s tradition. They choose organic farming to honor their conservation tradition and achieve land stewardship goals. Farmer #06 said: “I feel I have a responsibility to try to leave the land better than I received.” And #06’s father added: “I’m the second-generation farmer here. My dad before me, we have always been very conservation-minded.”

The nostalgia of the old-way farming (6 farmers)

With the industrialized agriculture operation, conventional agricultural production may make farmers feel like being apart from the land. Six organic farmers indicated they cherished the memory of the “old way of farming,” and they want to bring back the feeling of land attachment. Farmer #09 recalled the farm they used to have in his childhood, and he said: “Without question, it's in my blood to do things that are more closely connected to the land. When I grew up, I was raising pigs outdoors. It was row cultivating the corn instead of using chemicals….And I became an adult and I started to have a family, I realized that the way we farm (conventionally) today pretty much leaves out all the fun stuff, you know, it's like all the things that I look back on and really cherish and see that they were valuable in my development.”

Self-challenges (4 farmers)

Four farmers viewed organic farmers as a self-challenge opportunity. For instance, farmer #12 made the organic adoption decision in the year 2000. When he described his decision, he said: “When the millennium came, people have this feeling it's the millennium. I want to do something (different), and that was what I did. So it's like if I’m gonna do this, I’m gonna do it. So I did it in 2000. I transitioned all of this farm to organic.”

God’s will (4 farmers)

Four organic farmers actively identified themselves as Christian, and they believed they are responsible for taking care of the land God created. Christian farmers saw organic farming is a way to follow God’s will and put more trust in their faith. Farmer #11 said: “I'm a Catholic, and so that's important. So, this is God's creation and we're to be stewards and take the best care of it. And so that's an important factor in organic farming.”

Compatible with the existing system (4 farmers)

Four organic farmers indicated they had diversified farming operation with extended crop rotations even before they officially started organic farming. They saw many of their practices already compatible with the requirement of organic farming. So, the compatibility with their existing farming system motivated them to adopt organic farming. Farmer # 06 had dairy operation besides grain operation, and he said: “We already had the crop rotations with the cows anyway… It was compatible with the dairy.”

Family's support (4 farmers)

In the interview, four organic farmers emphasized their decision to adopt organic farming was a family-decision. They received significant encouragement from family members that support the farmers to convert their farms to organic farming. Farmer #05 described how his son inspired him to adopt organic farming: “Well, my son, he had the idea of planting apple trees and then they'd be organic and we would make the apples into a hard apple cider. And so I guess that was kind of the impetus to go down the road of organic. Farmer #02 shared about how his wife insisted on organic farming: “And my wife said that if you want a farm that you have to do it organically. She was into the organic. When she read things about putting fish genes in strawberries, she was pretty adamant about it.”

Quantitative analysis of survey

Based on the results of the interview, we initially developed 21items to identify motivating factors of farmers to adopt organic grain farming. We first conducted an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to identify the motivating factors underlying the 21 items. We removed items with factor loading less than 0.60 and retained 14 items with a 7-factor solution. Table 1 presents the results of EFA and the descriptive statistics of the items loaded in each factor. In addition, to examine if there are any differences between pioneer organic farmers (who started organic farming before the year 2000) and contemporary organic farmers (who started organic farming on the year 2000 or later) in terms of the organic adoption motivations, we conducted independent T-tests for each factor.

|

Table 1. Exploratory factor analysis farmers’ motivating factors |

||||||

|

Factor |

Items |

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

Factor loading |

Independent T-test |

|

Personal Health Concern (M=4.38) |

To minimize my exposure to toxic chemical |

257 |

4.47 |

0.81 |

0.73 |

t (248)=1.59, p=0.12 |

|

To create a safer environment for my family |

256 |

4.29 |

0.81 |

0.77 |

||

|

Economic Drivers (M=4.32) |

To earn enough income to sustain my farm operation |

257 |

4.49 |

0.69 |

-0.98 |

t (249)=-1.61, p=0.11 |

|

To capture additional profit from organic price premium |

257 |

4.40 |

0.67 |

-0.65 |

||

|

Natural Resources Improvement (M=4.32) |

To improve soil health |

255 |

4.47 |

0.72 |

0.99 |

t (247)=0.98, p=0.33 |

|

To improve the water quality in my watershed

|

256 |

4.16 |

0.84 |

0.72 |

||

|

Public Health Concern (M=3.98) |

To meet consumer demand for healthy food |

255 |

4.00 |

0.84 |

0.68 |

t (247)=1.56, p=0.12 |

|

To address my concern about public health associated with our agriculture and food system |

256 |

3.96 |

0.95 |

0.83 |

||

|

Compatibility (M=3.75) |

My family supported me to adopt organic farming |

256 |

3.79 |

0.99 |

0.69 |

t (247)=0.053, p=0.96 |

|

My pre-existing operation’s system fits well with organic grain operations |

254 |

3.70 |

0.97 |

0.70 |

||

|

Honors and Beliefs (M=3.54) |

To honor my family farm’s tradition of conservation |

256 |

3.49 |

0.90 |

0.69 |

t (246)=2.07, p=0.04* Mean difference = 0.23 |

|

To honor my religious beliefs |

255 |

3.14 |

1.08 |

0.80 |

||

|

To farm in harmony with nature |

256 |

3.98 |

0.97 |

0.71 |

||

|

Self-Challenge Personality (M=3.39) |

To challenge myself |

253 |

3.39 |

0.98 |

0.60 |

t (245)=0.48, p=0.63 |

|

Note. Items were measured on 5-point scale: 1= Strongly disagree; 2= Disagree; 3=Neutral; 4=Agree; 5=Strongly agree. Independent T-tests were tested between farmers started organic farming before and after the year 2000. |

||||||

According to Table 1, the premier factors motivated farmers to adopt organic grain farming are Personal Health Concern, Economic Drivers, and Natural Resources Improvement. The secondary motivating factors include Public Health Concern, Compatibility and Honors and Beliefs. The least influential motivating factor is Self-Challenge Personality. The results of independent T-tests show that Honors and Beliefs is the only motivating factor significantly different between pioneer organic farmers and contemporary organic farmers. All other motivating factors are not significantly different between the two groups of organic farmers. This finding indicates ideological honors and beliefs, as a motivating factor, more strongly motivate pioneer organic farmers than contemporary organic farmers. Other motivating factors including the economic driver, natural resources improvement, concerns for personal and public health, compatibility, and self-challenge personality equally motivate both pioneer and contemporary organic farmers.

Challenges

By interviewing the organic farmers about the barriers and challenges they experienced in the process of adopting organic grain farming, we identified multiple challenges for organic grain farming adoption in Iowa. In summary, we discovered five major areas of challenges that impeded farmers' adoption of organic grain farming. Table 2 presents the specific types of challenges in each area. Based on the challenges we identified in the interview, we developed 28 items in the survey to measure its challenging levels. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of each surveyed challenge items.

|

Table 2. Challenges of Organic Grain Farming Adoption in Iowa |

||||||

|

Area of challenges |

Specific challenges |

|||||

|

Operation and management |

Weed control |

Time demanding |

Labor intensity |

Adverse climate |

No-till system |

Cover crop management |

|

Marketing |

Poor local marketing infrastructure |

Transitional crop marketing |

Organic small grain marketing |

Organic hay marketing |

|

|

|

Information and inputs |

Extension education at the local level |

Machinery fit to organic production |

|

|

|

|

|

Social pressure |

Negative social interactions |

Tension with conventional farmers |

|

|

|

|

|

Institutional |

Agents lack knowledge |

The complexity of government programs |

Lack of flexibility in government programs |

|

|

|

|

Table 3. Challenges of organic grain farming adoption

|

||||

|

Challenge Area |

Items |

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

|

Operation challenges (M=3.02) |

Weed control |

252 |

3.83 |

1.11 |

|

Organic farming is highly sensitive to the weather |

252 |

3.40 |

1.27 |

|

|

Soil fertility |

251 |

3.00 |

1.14 |

|

|

Insect control |

252 |

2.93 |

1.08 |

|

|

Plant disease control |

252 |

2.81 |

1.07 |

|

|

Difficult to farm organically on hilly ground |

251 |

2.79 |

1.24 |

|

|

Difficult to integrate no-till operation into organic farming |

246 |

2.75 |

1.48 |

|

|

Cover crop management |

252 |

2.62 |

1.05 |

|

|

Marketing challenges (M=2.71) |

Lack of organic small grain market |

252 |

2.90 |

1.29 |

|

Lack of transitional grain market |

249 |

2.88 |

1.35 |

|

|

Lack of organic hay market |

249 |

2.81 |

1.36 |

|

|

Lack of local organic marketing infrastructure (e.g., elevators) |

252 |

2.66 |

1.31 |

|

|

Lack of organic corn and soybeans market |

252 |

2.32 |

1.22 |

|

|

Policy challenges (M=2.54) |

Complexities of certification process |

252 |

3.02 |

1.16 |

|

Crop insurance policies are not favorable to organic farming |

247 |

2.30 |

1.39 |

|

|

Complexities of governmental programs |

248 |

2.29 |

1.23 |

|

|

Financial challenges (M=2.38) |

High financial risk in the transitional period |

249 |

2.77 |

1.29 |

|

Getting loans for organic farming enterprise |

250 |

1.98 |

1.07 |

|

|

Input and information challenges (M=2.22) |

Local extension agents lack expertise in organic farming |

248 |

2.56 |

1.25 |

|

Finding organic inputs |

252 |

2.31 |

1.03 |

|

|

Finding the necessary machinery for organic farming |

252 |

2.16 |

1.13 |

|

|

Insufficient educational programs for organic farming |

253 |

2.13 |

0.95 |

|

|

Lack of skills to setup/operate machinery |

252 |

1.95 |

1.01 |

|

|

Social pressure (M=2.19) |

Negative attitude against organic farming from other farmers |

251 |

2.39 |

1.28 |

|

Feelings of isolation in the local rural community |

252 |

2.00 |

1.20 |

|

|

Land tenure challenges (M=2.16) |

Unstable land leasing agreement for organic operation |

251 |

2.13 |

1.23 |

|

Lack of owned land that I control |

249 |

2.20 |

1.27 |

|

|

Items were measured on a five-point scale: 1=Not a challenge at all; 2=Minor challenge; 3=Somewhat challenge ;4=Moderate challenge ;5=Serious |

||||

Combining the results and findings from both interviews and surveys, we found specific challenges of organic farming adoption have evolved over time as changes took place on institutional, technical, and climatic factors. 1) Operational challenges are the most prevalent challenges. The operational challenges are centered on weed control. Good control of weed needs to cooperative weather, which makes organic farming are highly sensitive to climatic factors. 2) Marketing became easier but not for all situations. Farmers indicate nowadays, the marketing of certified organic row crops (soybeans and corn) is not difficult. But the challenges are marketing of transitional grains, small grains and hay crops. 3) Agricultural policies have become more favorable to organic farming than before, but simpler and more straightforward regulation procedures are preferred by farmers. 4) Financial risks during the transitional period are still existed as a minor to somewhat challenging. The risks are mainly caused by low profitability during the transitional period. Nowadays, most bankers have a better understanding of organic farming’s market opportunities, and they are no longer resistant to finance organic farmers’ production. 4) As more supports from USDA, local land grant universities and non-profit farmers’ organizations (such as Iowa Organic Association and Practical Farmers of Iowa) have invested significant efforts in both research and education related to organic farming in the past two decades. The information challenges have been relieved. But farmers still see local extension agents lack expertise in organic farming is minor to somewhat challenging. As more organic agriculture enterprises including organic seeds, fertilizers, and small machinery companies started to operate in Iowa, the organic input challenges have also been alleviated. 5) The survey shows social pressure is a minor challenge to organic farmers. In the interview, many farmers indicated the social pressures from their neighbor conventional farmers still exist. But organic farmers across Iowa tended to form a professional community by joining organic farmers’ organizations, attending organic farmers’ meetings, attending and joining organic field days. Farmers get both mentally and technically support from the organic community, and they become less brother by the negative social pressures from the conventional farmers. 6) Land tenure is not a major challenge because organic farmers prefer to remain a smaller operation size rather than expanding the land. Sustaining on the small farm actually acts as a motivation to adopt organic farming.

Strategies

Through asking questions like “How did you overcome those challenges?” in the interview, we discovered farmers have mainly employed operational strategies, marketing strategies, learning strategies, and financial strategies to overcome the adoption challenges. Based on the interview responses, we developed a list of 34 strategies that can be used to overcome the barriers and challenges of organic farming. Because of the extended length of the list, we only present the strategies that have been employed by more than 30% of farmers. Table 4 presents the specific strategies, percent of being taken, and descriptive statistics of the level of importance.

|

Table 4. Strategies farmers employed to overcome adoption challenges |

|||||

|

Strategy area |

Specific strategy |

Percent of being taken |

Level of Importance |

||

|

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

|||

|

Operational strategies |

Strategically adjust crop rotations |

86.2% |

232 |

3.98 |

1.01 |

|

Use of cover crops |

81.6% |

231 |

3.96 |

1.14 |

|

|

Start organic operation from a small scale |

81.1% |

226 |

3.43 |

1.04 |

|

|

Apply purchased organic fertilizer or manure |

79.1% |

225 |

3.92 |

1.11 |

|

|

Purchase older equipment |

72.4% |

220 |

3.15 |

1.17 |

|

|

Conduct on-farm experiments |

62.8% |

197 |

3.3 |

1.17 |

|

|

Share equipment with other farmers |

55.6% |

193 |

2.78 |

1.28 |

|

|

Start organic farming on CRP or hay land |

44.4% |

177 |

3.01 |

1.39 |

|

|

Marketing strategies |

Acquire marketing information from other organic farmers |

71.9% |

213 |

3.67 |

1.16 |

|

Sell organic grains following market trends without a forward contract |

61.7% |

210 |

2.82 |

1.09 |

|

|

Forward contract organic grains |

51.0% |

196 |

2.93 |

1.25 |

|

|

Acquire marketing information at organic conferences |

50.5% |

192 |

3.11 |

1.27 |

|

|

Sell organic grains directly to organic livestock producers |

45.4% |

178 |

3.22 |

1.25 |

|

|

Use organic market reports as marketing reference (e.g., |

33.2% |

169 |

2.45 |

1.25 |

|

|

Collaborate with other organic farmers to leverage marketing |

30.0% |

160 |

2.46 |

1.22 |

|

|

Learning strategies |

Ask other organic farmers about organic farming techniques |

83.7% |

241 |

4.01 |

0.99 |

|

Read general farm magazines for all types of farmers (e.g., |

65.3% |

223 |

2.83 |

1.06 |

|

|

Read farm magazines specialized in organic/sustainable |

59.7% |

210 |

3.22 |

1.18 |

|

|

Attend field days offered by organizations (e.g., PFI, Iowa |

55.1% |

203 |

3.25 |

1.30 |

|

|

Attend organic conferences (MOSES, Iowa Organic |

45.9% |

187 |

3.05 |

1.35 |

|

|

Ask older conventional farmers who have prior experience with non-chemical farming about farming techniques |

42.9% |

181 |

3.07 |

1.38 |

|

|

Establish a mentor-mentee relationship with another |

34.7% |

168 |

2.91 |

1.32 |

|

|

Research organic farming techniques on the internet |

32.1% |

169 |

2.57 |

1.51 |

|

|

Financing strategies |

Enroll in organic certification cost share program |

43.4% |

188 |

2.78 |

1.60 |

|

Enroll in government programs for financial assistance (e.g., |

31.6% |

172 |

2.22 |

1.44 |

|

|

Land tenure strategies |

Rent land from family members for stable leasing terms |

33.2% |

164 |

2.78 |

1.48 |

|

Note. Level of importance of each item was measured on five-point Likert scale: 1=Not important at all; 2=Slightly important; 3=Somewhat important; 4=Fairly important; 5=Very important |

|||||

According to Table 4, the strategies’ raking of importance level seems to be consistent with the percentage of being taken. We examined the relationship with Person Correlation. A strong positive correlation (r=0.93, p<.001) was found. We can conclude that farmers employ a certain adoption strategy because they think the strategy is important. 1) Top operational strategies are crop rotations, cover crops, and starting organic operation from a small scale. 2) Marketing strategies include diverse marketing methods (Forward contracting, spotting marketing, and direct marketing) and multiple marketing information sources (from other farmers, conferences, and USDA reports). 3) Because organic farming is knowledge and information-based innovation. Farmers employed learning strategies to fill the information and knowledge gap. Farmers employed both interpersonal learning and self-learning. Asking questions to other farmers, attending field days and conferences are important interpersonal learning strategies. Reading farming magazines and searching for information online are important self-learning strategies. Financing strategies and land tenure strategies are not as popular as the other three groups of strategies we just discussed. This is maybe 1) because land tenure was rated as a minor challenge for organic grain farming; 2) financial risks inherently exist in all farming enterprises, and there is no effective tool to lower the financial risks in the transitional period so far unless substantial policy changes happen. The certification cost-share program seems to attract a good proportion of farmers to enroll, but the actual financial help it provides is a small amount. Government programs for financial assistance have a relatively lower proportion of users, maybe due to its’ complexity, lacking flexibility, and local office agents are not knowledgeable enough about the programs. In summary, we suggest extension educators and organic specialists continue to promote operational strategies, marketing strategies, and learning strategies among new organic farmers. We also suggest policymakers optimize and develop more effective programs farmers can enroll to help with their financial challenges.

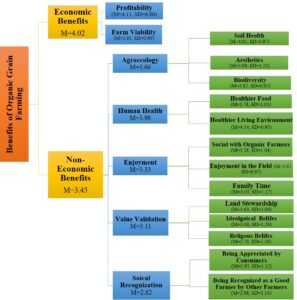

Benefits

We are interested in knowing what specific benefits farmers have experienced from your organic grain farming operation. Figure 3 presents the benefits that farmers experienced from adopting organic grain farming. We identified specific benefits farmers experienced from adopting organic grain farming from the interviews. Then we measured the level of benefit with surveys on a five-point Likert scale (1=Not a benefit at all; 2=Low level of benefit; 3=Medium level of benefit; 4=High level of benefit; 5=Very high level of benefit).

The interview identified 15 benefits. Ten of them are non-economic benefits and only two of them are economic benefits. Though farmers experienced more types of non-economic benefits than economic benefits, economic benefits outweigh non-economic benefits in terms of the level of benefits. In general, economic benefits, human health benefits, agroecology, and value validation are consistent with the motivations of the economic drivers, personal health concern, natural resources improvement, and honor and beliefs. The feelings of enjoyment are unexpected benefits that organic farmers experienced.

Needs for educational programs and delivery formats

Table 5 presents the results of farmers’ needs for educational programs. According to the table, and the response of interviews, we found:

- Many farmers think it is important to let more young people understand and accept the value of organic farming. They think young people are more open to new ideas. They like to see there are more young organic farmers in the future.

- Organic farmers think many conventional farmers did not know enough about organic farming and they have many misunderstandings about organic farming. The organic farmers suggest having more outreach educational programs targeted on conventional farmers with two focus areas: the potential profitability of organic farming; the agroecological principles behind organic farming.

- Several farmers agree that the transition period involves multiple rough challenges. The beginning farmer program should focus on transition techniques.

- Farmers like to see more research were conducted on a real-word farm setting across the state. Some farmers moderately criticize the past organic farming research conducted at the experiment station had too may controlled conditions, and they suggested to collect more on-farm data.

- Organic farming is labor-intensity and time-demanding in the growing season. Farmers think wintertime is a better time for them to have more learning activities.

|

Table 5. Needs for educational programs |

|||

|

Program |

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

|

Educate younger people about organic agriculture |

248 |

3.80 |

1.04 |

|

Educate conventional farmers about organic agriculture |

246 |

3.45 |

1.21 |

|

Beginning farmers' programs focused on organic transition |

244 |

3.43 |

1.16 |

|

More on-farm research projects related to organic farming |

247 |

3.31 |

1.23 |

|

More winter educational programs for organic farming |

244 |

3.24 |

1.07 |

|

More agronomic research on organic farming |

246 |

3.24 |

1.27 |

|

More extension publications on organic topics |

246 |

3.05 |

1.09 |

|

Train extension filed staff about organic farming |

246 |

3.05 |

1.22 |

|

More market research on organic farming |

248 |

3.05 |

1.24 |

|

Local yield data for organic grains |

242 |

2.96 |

1.13 |

|

Organic farming manuals |

246 |

2.92 |

1.11 |

|

Certification training |

244 |

2.88 |

1.06 |

|

Local organic farmers networks |

242 |

2.87 |

1.24 |

|

More organic agriculture courses offered by universities |

246 |

2.76 |

1.32 |

|

Note. Items were measured on 5-point Likert Scale: 1=Not Needed; 2=Slightly Needed; 3=Somewhat Needed; 4=Moderately Needed; 5=Strongly Needed |

|||

Table 6 presents the results of the effectiveness of program delivery formats. According to the table, and the response of interviews. Farmers rated field days or pasture walks, one-on-one mentors, and farmer-to-farmer workshops as more effective formats than other formats. This finding reflects organic farmers prefer bottom-up communication channels and peer-learning approach over the top-down technology transfer approaches. It is consistent with farming’s ratings on learning strategies in the strategy section. Therefore, we suggest extension educators and organic specialists play a facilitator role who helps to build a knowledge-sharing platform within programs.

|

Table 6. Effectiveness of program delivery formats |

|||

|

Program delivery format |

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

|

Field days or pasture walks |

233 |

3.73 |

0.99 |

|

One-on-one mentors |

226 |

3.50 |

1.10 |

|

Farmer-to-farmer workshops |

220 |

3.37 |

1.12 |

|

YouTube (or other) online videos |

218 |

2.38 |

1.25 |

|

Webinars (“farminars”) |

216 |

2.31 |

1.15 |

|

Workshops by professors, extension or consultants |

224 |

2.80 |

1.07 |

|

Note. Items were measured on 5-point Likert Scale: 1=Ineffective; 2=Slightly effective; 3=Moderately effective; 4=Effective;5=Highly effective |

|||

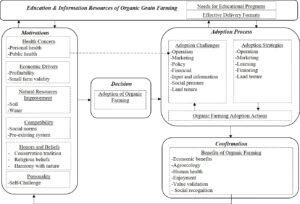

A framework of organic grain farming adoption

After separately discussed the motivations, challenges, strategies, benefits, and need for educational programs regarding organic grain farming adoption. We developed the following framework (Figure 4) to demonstrate the comprehensive process of organic grain farming adoption.

Farmers’ decision to adopt organic grain farming is motivated by their health concerns, economic drivers, natural resources improvement, compatibility, honors and beliefs, and the self-challenge personality. Farmers need to be exposed to basic information about organic farming to become interested in organic farming and conceive more and stronger motivations as they explore more information. After farmers make a decision to adopt organic grain farming, they start to take action. Then farmers will meet a series of challenges impeding their adoption actions. Farmers need to go to the information resources and educational programs related to organic grain farming to develop multiple adoption strategies to overcome the challenges. The adoption action process may be an iterative process that farmers encounter more challenges, get more information and education, develop additional strategies until all major challenges are overcome. Finally, the adoption enters into the confirmation stage that farmers started to experience different benefits of organic farming such as better profitability, healthier living environment, less erosion etc. If farmers found the benefits match their adoption motivations, their adoption decision will be enhanced, and farmers will confirm organic grain farming fit their need. We suggest presenting this framework to new organic farmers and farmers who are interested in organic farming. By presenting this framework to farmer audiences interested in adopting organic grain farming, farmers will have a clear vision of their adoption processes. In addition, we also suggest organic specialists develop training materials based on our framework as it 1) directly discovered the concerns and needs of organic farmers; 2) identified barriers to organic conversions; 3) and provided extensive verified strategies that can be used by future farmers.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

To date, this project has delivered four presentations to organic agriculture conferences.

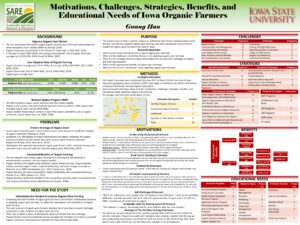

- "Identify Motivations, Challenges, and Educational Needs of Organic Grain Farming Adoption". Paper presented at 2019 Annual Meeting of the Rural Sociological Society, Aug 7-10, 2019. Richmond, VA. The project graduate coordinator presented the paper to about 35 audiences including 25 researchers and 10 educators.

- "Towards Effective Organic Education: Identifying Motivations, Challenges and Educational Needs of Organic Grain Farmers". Research forum and poster presentation at 2019 MOSES Conference, Feb 21-23, 2019, La Crosse, WI. The project graduate coordinator presented the poster to about 30 audiences including 20 farmers, 3 organic professionals from organic industry companies, 2 extension educators from land grant universities, and 5 graduate students.

- "Motivations, Challenges, Strategies, Benefits, and Educational Needs of Iowa Organic Farmers" Poster presentation at 2018 Iowa Organic Conference, Nov 18-19, 2018, Iowa City, IA. The project graduate coordinator presented the poster to about 25 audiences including 20 farmers, 2 extension educators, 2 government agencies IDALS, and a program director from OTA.

- " Motivations, Challenges, Strategies, Benefits, and Educational Needs of Iowa Organic Farmers" Poster presentation at 2018 Iowa Organic Association Annual Meeting, Nov 27, 2018, Ames, IA. The project graduate coordinator presented the poster to about 14 audiences including 10 farmers, 2 educators from Iowa Organic Association, and 2 graduate students

Research Poster: Motivations, Challenges, Strategies, Benefits, and Educational Needs of Iowa Organic Farmers

The graduate coordinator entertained with an organic professional at 2019 MOSES conference

The project graduate coordinator was entertaining with a farmer audience at 2018 Iowa Organic Conference

Project Outcomes

By collecting and analyzing both qualitative and quantitative empirical data, this project addressed the gaps in the literature that lack understanding of the motivation, challenges, strategies, benefits, and educational needs of US Midwest farmers in adopting organic grain farming. This project also developed a framework that illustrates the complete process of organic grain farming adoption. The framework can help organic specialists and educators develop effective educational programs to 1) directly address farmers' concerns and motivations; 2) identify and overcome barriers of organic grain farming adoption; 3) promote the adoption of organic farming among grain farmers. The long-term outcomes of this study will eventually provide the basis for an increase in the domestic supply of organic grain, and then help organic livestock producers with a steady and affordable organic feed supply. Moreover, because grain operations have larger operating acreages than other agricultural enterprises, an increase in organic grain farming would lead to a wider and fundamental improvement on the environment, farm viability, and rural communities.

In this project, I have closely interacted with organic farmers through interviews, surveys, and giving presentations at organic farmers' conferences. Through those interactions, I have learned organic farmers are both idealistic and realistic at the same time. They have very strong ethics about human health, environment, natural resources, and sustainability, but they also have to face the political economy that is crucial to their farm's viability. Therefore, to achieve agricultural sustainability, as researchers, we need to study the farmers' behavior and decisions at both individual levels and institutional levels.