Final report for GNC16-225

Project Information

Feeding by herbivores induces production of volatile secondary plant metabolites that play important roles in mediating plant-insect interactions in agroecosystems. By acting as prey location cues for predator and parasitoid insects, herbivore induced plant volatiles (HIPVs) can increase interactions between natural enemies and prey and have become an area of interest for biological pest control programs that seek to attract natural enemies into production fields from natural habitats. For specialty crop growers of the North Central Region, use of HIPV lures could have particular value in management programs as alternatives to chemical pest controls. However, such programs must be tailored to specific crops, target pests and relevant natural enemies to be effective.

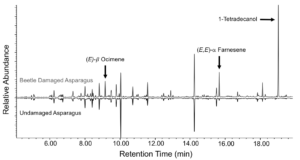

Our previous research found that asparagus produces significantly higher concentrations of HIPVs (e)-beta-ocimene, (e e)-alpha-farnesene, and (1)-tetradecanol than healthy plants following 48 hours of feeding by common asparagus beetle larva (Crioceris asparagi), a monophagous feeder of asparagus globally (Fig. 1). Y-tube olfactometer tests with a polyphagous predator, the convergent lady beetle (Hippodamia convergens), demonstrated some attraction to asparagus HIPV’s at specific concentrations in a lab setting. The goal of this research was to build upon these findings to develop a field deployed HIPV lure that can attract natural enemies from field border habitats into production fields to increase natural enemy-prey interactions in an effort to control key crop pests.

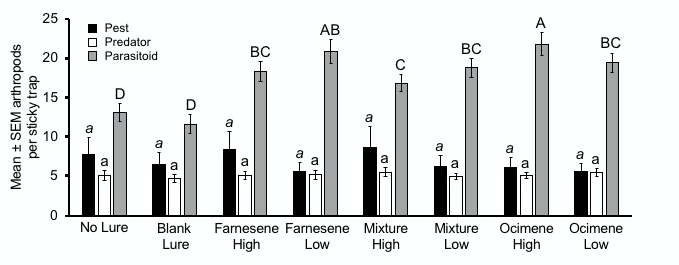

We placed HIPV lures baited with two concentrations of ocimene and farnesene, mixtures of the two, and controls on field edges of 12 commercial asparagus fields for 8 weeks, post-harvest (Fig. 2). Immediately following lure deployment, we released 100 marked convergent lady beetles 10 m from each lure, into the field border habitat, to determine if this predator was attracted to lures in the field. Lures were deployed with sticky traps, replaced weekly, and all insects collected on the traps were identified as crop pests, predators, parasitoids, or marked lady beetles. We found that in all HIPV lure concentrations and mixtures tested that parasitoids were more attracted to HIPV lures than our controls. However, predators were not attracted to lures and we only recaptured three marked lady beetles that were released over the entire experiment. Fortunately, crop pests were also not attracted to our lures. Our research findings demonstrate that HIPV lures deployed in asparagus agroecosystems may increase parasitoid-pest interaction, without increasing pest pressure, by recruiting parasitoids from field border habitats into field edges.

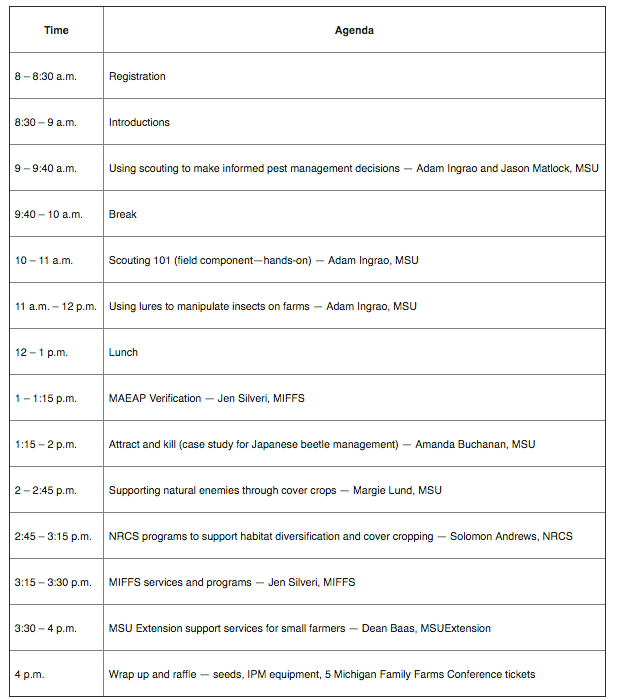

As part of this project, we conducted educational outreach to promote the use of lure technology in scouting and biological pest control by small farmers in Michigan. This effort resulted in seven conference presentations, five research poster presentations, one field day, and is part of a larger manuscript currently under review by a peer-reviewed journal. Conference and poster presentations were made to researchers and farmers, while the field day was focused on beginning farmers and farmer veterans (military veterans). Our field day was attended by 20 farmers (2 of which were veterans) (Fig. 3). The workshop provided training on the use of lure technologies to support pest management, the use of cover crops to support natural enemy communities, the use of attract and kill technologies for pest management, and how to access resources and programs through Michigan State University Extension and USDA to support adoption of these management practices. A formal survey was conducted at the end of the workshop and the results are reported herein.

The primary goal of this research was to investigate the use of herbivore induced plant volatiles (HIPV) in field deployed lures as recruitment tools for natural enemies of common asparagus beetle (Crioceris asparagi) and the asparagus miner (Ophiomyia simplex) in an effort to increase natural enemy-prey interactions. Educational outcomes were accomplished through oral and poster presentations, an on farm workshop, and state-wide outreach with Michigan Food and Farming Systems (501c3) which educated researchers and farmers on the use of lures in agricultural pest management and scouting. Overall, we sought to increase grower adoption of biological pest management strategies in specialty crops, increase predator-prey interactions in asparagus agroecosystems through HIPV lures, and decrease the use of broad spectrum insecticides in asparagus production in the North Central Region.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

- (Educator)

Research

Lures were developed for experiments to test the attraction of asparagus HIPVs to arthropods in the field using ocimene and farnesene (ocimene mixture of isomers and farnesene mixture of isomers – Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) because of their presence in herbivore induced asparagus plants, availability, and low cost. Lures were comprised of a cotton ball (~0.28 g, Covidien LLC, Mansfield, MA, USA) placed in a 2 ml microcentrifuge vial (Denville Scientific Inc., Holliston, MA, USA) and wrapped with black tape (Scotch Duct Tape, The 3M Company, St. Paul, MN, USA) to prevent photolysis of compounds. Ocimene and farnesene lures were tested at different concentrations either as isolates or as mixtures of the two compounds. The following lures were evaluated: no lure (negative control), blank lure (positive control), farnesene high (1000μl farnesene), farnesene low (750 μl farnesene), ocimene high (500μl ocimene), ocimene low (300μl ocimene), mixture high (1000μl farnesene + 500μl ocimene) and mixture low (750μl farnesene + 350μl ocimene). Vials were opened and attached horizontally to the top of a 1 m tall metal pole with garden wire, directly below a yellow sticky trap (13 × 8 cm, Great Lakes IPM, Inc., Vestaburg, MI, USA). Immediately following lure deployment, 100 marked convergent lady beetles (Rincon-Vitova Insectaries, Ventura, CA, USA) were released 10 m away from each lure, into the field border habitat, as part of a marked release and recapture experiment.

Field testing of lures was initially conducted from July – August, in six commercial asparagus fields in Oceana County (MI, USA). Field sites were all within 8 km of Lake Michigan and had a consistent eastwardly prevailing wind from the lake. All fields used in the experiment had eastern field margins that were along unmanaged forests (mixtures of conifers and deciduous hardwoods) and lures were placed on the eastern crop edges 10 m apart so that the prevailing wind carried volatile signals into the wooded field border to attract natural enemies into the asparagus field from these natural habitats. Sticky traps and lures were replaced weekly for 5 weeks and pests, predators, parasitoids, and marked lady beetles collected on the traps were quantified.

To test the effect of field position on the efficacy of lures, we continued sampling for an additional 3 weeks from August – September 2016, adding six research sites with lures on the southern field edge of asparagus fields with forested southern margins. Following the same protocol outlined above, we collected sticky traps and determined abundance of pests, predators, and parasitoids weekly.

The effect of field position on the number of arthropods trapped was determined; however, since it had no effect, position was dropped as a fixed factor and total abundance for pests, predators, and parasitoids were analyzed with a mixed effects model (GLMER, package = “LME4”) with Poisson distribution. This analysis can account for an unbalanced experimental design since lures and traps were sometimes run over by farm equipment and destroyed. Lure treatments were fixed effects, and field and date were random effects. Full and reduced models were considered and models were selected for best fit based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Least squares means multiple comparisons, with Bonferroni correction, were conducted post-hoc (α = 0.05; package = “MULTCOMP”). Over the course of eight weeks of sampling, only three marked lady beetles were recaptured following release. Due to the low sample size, lady beetle recapture was not analyzed and is not presented.

All lures developed from volatile compounds found in the headspace of asparagus beetle damaged plants attracted more parasitoid wasps to yellow sticky traps over the 8 week sampling period than controls (Χ2 = 316.14, df = 7, p < 0.01; Fig. 4). High concentration ocimene lures attracted significantly more parasitoids than all other treatments (z ≤ -4.55, p < 0.01), except low farnesene concentration lures (z = -1.99, p = 0.48). Low farnesene concentration lures attracted 19 % more parasitoids than high concentration lure mixtures of ocimene + farnesene (z = 3.84, p < 0.01), and at least 37 % more than controls (z < -10.17, p < 0.01); however, they performed similar to high farnesene (z = -2.58, p = 0.16), low ocimene (z = 1.82, p = 0.61), and mixtures of low ocimene + farnesene lures (z = 2.58, p = 0.17). High farnesene, low ocimene and both mixture lures all performed similarly and all attracted significantly more parasitoids than the control treatments (z ≤ -6.24, p < 0.01). Predatory arthropods did not respond differently to our lures compared to the control treatments (Χ2 = 5.71, df = 7, p = 0.57). Likewise, key obligate asparagus pests, common asparagus beetle and asparagus miner, showed no significant attraction to any of the lures tested compared to the controls (Χ2 = 4.88, df = 7, P = 0.68).

Our research is the first to investigate the chemical ecology of post-harvest asparagus in a field setting and the use of asparagus HIPVs to manipulate spatial relationships between key pests and natural enemies. Field experiments demonstrated that lures baited with HIPVs of asparagus, ocimene and farnesene, attracted parasitoids without attracting pests, but had no impact on predator recruitment, which may have implications for biological control of key asparagus pests.

Parasitoid attraction to HIPVs is well documented in multiple systems targeting numerous parasitoid taxa. As host location cues, HIPVs aid parasitoids in navigating complex infochemical webs in agroecosystems to locate appropriate hosts; therefore, it is not surprising that HIPVs of asparagus are attracting parasitoids. Conversely, predators primarily employee hunting strategies that largely don't depend on volatile cues. Predators hunt for prey through several strategies (sit and wait, random search, trapping, and direct pursuit) but these strategies are largely unrelated to the active use of HIPV cues in prey location. This may explain why we saw no increase in predator attraction to HIPV lures over controls and also explains why marked lady beetles were not attracted to HIPV lures in a field setting.

Spatial relationships within agroecosystems are important to consider when developing volatile lures to attract natural enemies for pest control. Field size plays an interesting role in recruitment of natural enemies and dramatic reductions in pest suppression occur as field sizes increase in simulated models, with smaller field areas receiving reductions in pests while larger fields realize little pest suppression. In Michigan, asparagus fields are small (our fields ranged from 4 – 17 ha) and recent research has shown that key asparagus pests congregate on field edges in post-harvest asparagus, while their natural enemies primarily occupy the field margin habitats, ~10 m outside of the field. This spatial relationship between key pests and natural enemies is unique and offers an opportunity to manipulate spatial relationships to favor pest suppression and underscores the importance of a system specific approach when using HIPVs as natural enemy recruitment tools.

We sought to recruit natural enemies from the field margins to the field edge with volatile lures to increase trophic interactions. However, the bioactive range of volatile cues is variable and the literature reflects this with bioactive ranges demonstrated from 1 – 10 m. Our findings have indications of the bioactive range of our lures because our fields were selected for uniformity of border habitat and distance between the field edge to the border habitat; however, field margin habitats don’t have finite boundaries. This makes conclusions regarding the bioactive range of our lures difficult to assess in a commercial system and is beyond the scope of this study.

The use of HIPV lures in agriculture should be regarded as one of the many tools available through integrated pest management and should incorporate scouting, management thresholds, and degree day models to ensure timing of lure deployment is synchronous with pest life stages that are targets for control. The uniqueness of specialty crop pest management, which most often is mode of action limited but has high value, makes alternative management strategies for pests, such as HIPV lures, an area that should be given much more research attention to reduce overall pesticide use. However, as we have demonstrated in this study, this could mean that individual strategies must be developed for each specialty crop system, perhaps even individual cultivars. Coordinated efforts between producers, pest managers, and chemical ecologists could facilitate meaningful pest management solutions that don't rely on pesticides and further our understandings of the role HIPVs play in agroecosystems.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

Consultation: Met with Jeremy Huffman (owner of Huffman's Homestead, Swartz Creek,MI) in July 2016. Discussed the use of biological controls to manage pests in brassicas and the use of predatory lures (Benelure and PredaLure) to support pest management.

Journal articles: The research presented herein is a component of a larger research project that has been submitted to Biological Control and is currently under peer-review for publication. The publication is entitled, "Natural enemy attraction to herbivore induced asparagus volatiles increases biological control of a key pest."

Published press articles: As part of promoting the workshop conducted on small farms pest management I published an Extension News article with Dr. Dean Baas. The article can be found here:

http://msue.anr.msu.edu/news/small_farm_insect_pest_management_workshop_held_aug_13_2017

Oral presentations:

- Knowing Your Place: Combining Farm Specific Knowledge with Scouting to Form Organic Pest Management Plans. By Adam Ingrao and Jason Matlock. Michigan Family Farms Conference – Kalamazoo, MI – February 3, 2018.

- Biological Pest Control Basics: Strategies for the Use of Predator and Parasitoid Insects in Landscape and Nursery Settings. By Adam Ingrao and Zsofia Szendrei. Great Lakes Trade Expo – Lansing, MI – January 22, 2018.

- Asparagus Insect Pest Management. Zsofia Szendrei, Amanda Buchanan, Adam Ingrao, Jason Schmidt, and Matthew Grieshop. Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Expo – Grand Rapids, MI – December 8, 2017.

- Asparagus Insect Pest Management. Amanda Buchanan, Adam Ingrao, and Zsofia Szendrei. Michigan Asparagus Advisory Board annual meeting – DeWitt, MI – February 17, 2017.

- Biological Pest Control Basics: Strategies for the Use of Predator and Parasitoid Insects. By Adam Ingrao and Zsofia Szendrei. Farmer Veteran National Stakeholder Conference – East Lansing, MI – November 30, 2016.

- Knowing Your Place: Combining Farm Specific Knowledge with Scouting to Form Organic Integrated Pest Management Plans. By Adam Ingrao and Jason Matlock. Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Expo – Grand Rapids, MI – December 8, 2016.

- Alternative Pest Management Strategies for Specialty Crops. By Amanda Buchanan, Adam Ingrao, Jason Schmidt, Matthew Grieshop, and Zsofia Szendrei. International Congress of Entomology– Orlando, FL – September 26, 2016.

Poster presentations:

- Natural Enemy Attraction to Herbivore Induced Asparagus Volatiles. By Adam Ingrao and Zsofia Szendrei. Great Lakes Fruit and Vegetable Expo – Grand Rapids, MI – December 5-7, 2017. Entomological Society of America annual conference – Denver, CO – November 5-8, 2017. International Society of Chemical Ecology/Asia-Pacific Association of Chemical Ecologists Conference – Kyoto, Japan – August 24, 2017.

- Developing Innovative Tactics for Pest Management in Asparagus. By Amanda Buchanan, Jason Schmidt, Adam Ingrao, Matthew Grieshop, and Zsofia Szendrei. Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Expo – Grand Rapids, MI – December 8-10, 2015. Entomological Society of America annual conference – Minneapolis, MN – November 15-18, 2015.

Workshop/field day: Small Farm Pest Management: Informed Decisions and Sustainable Solutions. By Adam Ingrao. Michigan Food and Farming Systems Field Day – Tilian Farm Development Center, Ann Arbor, MI – August 13, 2017.

The field day was a partnership between MSU, MSU Extension, the Michigan Agriculture and Environmental Assurance Program (MAEAP), USDA, and Michigan Food and Farming Systems. We had 20 participants for the day long workshop which included training on the use of: HIPV lures in pest management, cover crops to support natural enemies, attract and kill technologies in pest management, MAEAP farm verification, and USDA and MSUE programs and resources available to aid growers in adopting these management practices. The field day agenda is below:

Project Outcomes

Attendees of our field day were encouraged to provide feedback through a formal evaluation and 65% completed our evaluation survey. Of those, 92% reported an increase in the likelihood that they would use volatile lure technologies for pest management on their farms. The workshop also highlighted other sustainable pest management techniques; incorporation of cover-crops to support natural enemies and using attract and kill technologies for pest management. Participants reported a 62% increase in the likelihood they would use cover crops and 77% reported an increase in the likelihood to use attract and kill technologies for pest management. These results are encouraging and demonstrate that small farmers (less than 50 acres of production) are interested in sustainable pest management solutions in many different forms.

As part of the field day we also presented information on how to support these practices, and overall environmental stewardship on farms, though MAEAP verification, MSU Extension support services, and USDA programs that support conservation practices that support natural enemies. Our participants indicated strong likelihood that they were more likely to apply for USDA conservation programs (85%), have their farm verified by MAEAP (62%), and use MSU Extension services (100%).

Overall, these reported results indicate that we have impacted the perception of alternative pest management tactics (alternatives to chemical control) and possible utilization of services that support conservation practices on farms. This will contribute to the sustainability of these participant's farm operations and will directly impact the surrounding environments of their farms through decreases in overall pesticide use and supporting diverse habitats that support natural enemy communities.

Over the tenure of this grant we had the opportunity to present this research to academics and farmers throughout the NCR. I have learned that utilization of HIPV lures to manipulate spatial relationships between prey and natural enemies to drive biological pest control is well known amongst researchers but largely unknown in small farmer communities. It is clear from the results of our field day evaluation form (results reported in Project Outcomes) that growers are interested in these technologies as pest management tools, but more effort on the part of researchers and Extension personnel needs to be made to help growers understand their function and application in agroecosystems.

This research was continued following the results presented here and identified that ocimene lures increase the biological control of asparagus miner (a co-occuring pest with asparagus beetle) by Pteromalidae parasitoids. Additional research is necessary to refine the lures used in this research to create a controlled release dispenser. Pteromalids are the most abundant parasitoid family in asparagus fields in Michigan and their attraction and resulting increases in biological control of a key asparagus pest should be an indication that HIPV lures may be able to increase biological control of asparagus miner in commercial settings.