Final report for GNC16-228

Project Information

Rotational grazing partnerships between public land managers and private cattle producers offer the potential to maintain and improve public grasslands while increasing the profitability of grass-fed beef and dairy. While recent constraints on public land management in Wisconsin have allowed detrimental encroachment of woody and non-native plants on state grasslands, research has shown that rotational grazing can reduce woody species, enhance soil and water quality, and improve biodiversity. Improved understanding of rotational grazing and its effects on plant communities, soil properties, and the potential socioeconomic opportunities of grazing partnerships will provide critical insights for grassland conservation, producer profitability, and many ecosystem services. As part of an interdisciplinary research team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, my goals are (1) to characterize plant and soil attributes on public grassland sites and (2) to develop and recommend a set of best practices for public-private partnerships in agricultural research, and to evaluate the adoption and utility of those practices. This work is part of a five-year collaboration between UW-Madison, land managers from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR), and private cattle producers to explore grazing management on Wisconsin’s public grasslands.

Conducting ecological and social research simultaneously will provide unique and valuable information about the success of producer partnerships in research and public land management. Surveying plant communities and soils will inform conservation goals and cattle grazing plans, while developing best practices will manage the needs, interests, and expectations of the partnerships around those plans. The focus on outreach and dissemination of project findings will encourage input, critique, and collaboration between producers and public institutions. This research will contribute to supporting new agricultural opportunities for farmers, improving environmental quality, maintaining critical grassland habitat for wildlife and public recreation, and developing educational literature on conservation agriculture and evaluation for future partnerships.

Results from this two-part research project will contribute to assessing rotational grazing as a feasible land management tool in the Upper Midwest. The primary outcomes are (1) increased knowledge of the dominant plant communities and soil conditions across a spectrum of public grasslands, and (2) development a set of best practices and evaluation tools to assess the actions of the project partners. From these two primary aims, there are four learning outcomes and two action outcomes that follow:

In the short term, the learning outcomes from the ecological data collection will (1) establish baseline characterization of plant communities and soil quality on public lands to inform grazing plans and monitor spatial and compositional changes under different types of management, and (2) collect hyperspectral images for maps and models of these lands to predict future changes. The best practices data collection will (3) document the goals and expectations of the producers, land managers, and researchers involved in pilot grazing projects while improving dialogue and inclusive decision-making, and (4) will help establish a set of best practices for the remainder of the five-year project.

For the short term action outcomes of this research, the ecological and social data will foster discussion between land managers, graziers, and researchers, provide material for local and national outreach events, and inform decision-making for the five-year project. In the long term, the research will expand the use of grazing with best practices as a successful and profitable management tool on public lands.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

Research

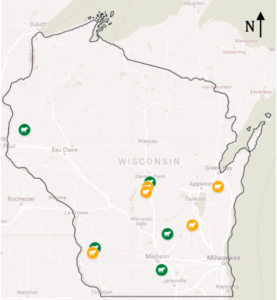

Plant and soil survey: A pre-grazing survey was conducted at 5 state wildlife areas where grazing management was implemented in 2016 (Fig. 1). Vegetation was sampled pre-grazing in June and during grazing in August, at 8 20x20m plots with five line-point transects. We used point-intercept methods to survey species composition and vegetation height, and clipped aboveground biomass in 4 0.5-m2 quadrats per plot, bagged and dried it at 65 °C for 2 days, and weighed for biomass determination. These samples were subjected to near infrared spectrometry (NIRS) analyses to assay components of the Relative Forage Quality (RFQ) index (Oates et al. 2011). We removed 15-cm deep, 2-cm diameter soil cores and tested them for total carbon and nitrogen. In addition, we worked with another lab group to take hand-held and leaf-level hyperspectral measurements in each plot, and low-altitude airborne hyperspectral images of the sites in August.

Grazing interviews: Five on-site, follow-up group interviews were conducted in near the end of the first grazing season in August of 2016 at each of the five pilot grazing sites with a total of 9 WDNR land managers and 4 graziers. The interviews focused on reflections on the first season of grazing projects, current observations of the vegetation and wildlife, and goals and plans for future years of grazing. The interviews were analyzed using open coding, guided by grounded theory (Chamaz 2000; Corbin and Strauss 1998) and its application in the work of previous agroecology research groups (Lyon et al. 2010; Lyon et al. 2011). Notes were read after each interview, and the topics of discussion were adjusted and refocused based on the previous interviews.

Plant and soil survey: Analyses of the plant and soil survey is ongoing, as we work to relate field measurements vegetation and soils with hyperspectral images to map plant species and forage quality on the grazing sites.

“Successful” grazing interviews: Central to the discussions at each of the five interviews was the idea of success: defining successful grazing for wildlife and vegetation, explaining what successful public-private partnership looked like, and what barriers to success might be on a short-and long-term basis. Though the pilot projects began under the premise of exploring a ‘win-win’ management scenario to support grassland management and grazing land access, the view of a ‘win-win’ scenario has increased in complexity over the course of implementation. As the pilot projects develop, we predict that graziers, land managers, and researchers will continue to expand their original vegetation and wildlife goals for grazing, and as such, the project practices should be constantly examined to assess their utility for meeting those goals. This report will discuss three themes that emerged as definitions of success, and current practices and activities to address them: versatile land management, cost-effectiveness, and community connections and change (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of definitions of success for pilot grazing project partnerships, on both large and small scales. Knowledge increases from academic research and practitioner experiences are implicitly included in every category listed.

|

Defining success |

Short-term success |

State-wide, long term success |

|

Versatile habitat management

|

· Shrub reduction · Increased plant diversity · Increased grassland bird usage |

· Improved state grassland landscape for patch-sensitive wildlife on public and private lands

|

|

Cost-effective partnerships

|

· Reduction of chemical and mechanical inputs, labor, time · Affordable land access · Cattle health and weight gains |

· New income from pasture rental · Labor and personnel savings · Increased grazing land access · Increased brokering of partnerships with up-to-date inventory of public land, interested graziers |

|

Community connections and change

|

· Partnerships with the agricultural community · Increased conservation buy-in from farming and hunting communities · Improved perceptions of ‘wasted lands’ |

· Increased interest and support for grassland habitat · Positive perceptions of WDNR as an agency · Broadened possibilities for alternative land management |

Versatile habitat and farm management: Though the ecological priorities of grazing have been at the forefront of this grazing research partnership, the discussion about how those ecological goals will be achieved has evolved over the course of the pilot projects. Increasing diversity of native vegetation, reducing woody and invasive species, and improving open habitat and structural diversity for grassland birds were consistent ecological goals across all grazing sites. The adaptability versatility of rotational grazing was also a frequent discussion topic throughout the interviews, that cattle could access areas that were not easily reachable by mowing or impractical for controlled burning or herbicide applications. While grazing is still subject to changes in weather or personnel, land managers interviewed explained that it is not as sensitive to timing as burning, nor does it pose the equipment challenges that mowing does. For their part, the vegetation and ecological goals of graziers still revolved around improving forage for their cattle over the course of the pilot projects, reducing shrubs and encouraging herbaceous growth and higher forage quality. Both groups expressed commitment to the learning process, looking at how the wildlife habitat changed and improved under grazing and how cattle responded to new vegetation conditions.

Cost-effectiveness: The emphasis on the cost-effectiveness of grazing management increased substantially from the initial site visits to the first grazing season. Though for the most part the WDNR personnel did not feel the grazing partnerships needed to generate income for the agency through rental fees, there was significant discussion around the ‘savings’ of grazing as a management tool. Reducing agency inputs including time, personnel, herbicides and equipment rentals were at the forefront of WDNR justifications for the grazing partnership. Balancing these savings with the cost of upfront investment and installation of fencing, water, and signage meant that land managers frequently clarified that grazing was not necessarily a money-making management scheme, but a money-saving one. Most graziers maintained that the partnership had to continue to be safe and profitable for their businesses. Cattle for the most part seemed to be achieving their target weight gains on the forage available, but grazier interest and investment of time for checking equipment and rotating the herds was, unsurprisingly, contingent on the health and safety of their cattle.

Both land managers and graziers expressed commitment to learning and interest in innovation and ongoing improvements to make the partnership more cost-effective. Graziers suggested mowing and haying in combination with grazing wherever possible to encourage herbaceous vegetation. There was frequent discussion and speculation about trials with multi-species grazing, using combinations of goats, cattle, horses, or sheep to target different vegetation issues. Both groups also expressed the possibility of subleasing grazing contracts to increase stocking densities on sites where cattle were not damaging shrub species and get other graziers involved on the landscape.

Community connection and change: The third theme to emerge from discussions around successful management was a social one: using grazing management and research partnerships as a way for both graziers and land managers to connect with their communities and positively change public perceptions. From the land managers’ standpoint, grazing was a way to change public opinion of the WDNR as ‘rule-enforcers,’ out-of-touch with the needs and interests of production and conservation in the community. Many explained that grazing demonstrated active management on the landscape, as a way to build trust and interest in conservation with the agricultural community who otherwise see public access grasslands as ‘wastelands.’ Graziers explained that the partnership could be a way to increase public knowledge and support about rotational grazing, moving away from the perception of all grazing as continuous overgrazing with negative ecological impacts. Some even saw the partnership as a way to add value to products, building conservation and the history of grassland grazing into their branding of beef and dairy products.

On a statewide and long-term scale, land managers explained that grazing partnerships could be a way to increase support for grasslands culturally, building interest within the agency and across both private and public lands. While both groups mentioned the opportunity of resting private pasture during periods of grazing on public land, some land managers suggested that these partnerships could be a way to encourage stewardship at home. They expressed hope that taking parcels of private land out of grazing rotation could benefit patch-sensitive wildlife, specifically grassland birds that could use the growth of home pasture as surrogate grassland, ultimately building improved wildlife corridors on a regional scale. They hoped to build interest in grasslands enough to justify agency positions for grassland ecologists and grazing specialists, to further build the knowledge and application of new management techniques in the upper Midwest. Land managers seemed to consider a partnership with the university and private graziers as a step toward more innovative practices by the agency in general, a way to shift institutional momentum away from traditional practices and more toward multifunctional land use and conservation.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

We gave 6 academic talks between Sept. 2016 - Dec. 2017, and co-organized 2 pasture walks (example pasture walk flyer) in August of 2017, reaching a variety of audiences including academics, farmers and land manager, and students.

In addition, we maintained a project website (https://grazingpubliclands.wisc.edu/) and the research project was covered in the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) magazine in April 2017 ("Greener Pastures"). We developed a draft fact sheet on grazing and grassland bird conservation in collaboration with the WDNR, and have one in progress on the larger grazing research project.

Presentations listed below:

- Landis, G., Grace, J., & Dirks, A. 2017. “Watching grass grow: Monitoring the processes and partnerships of grazing on Wisconsin’s public lands.” Poster. Green Lands, Blue Waters Conference. Madison, WI. (Green Lands, Blue Waters poster 2017)

- Dirks, A., Grace, J., & Landis, G. 2017. “Grazing Wisconsin’s Public Lands: A win-win for farmers and grassland habitat?” Presentation. Green Lands, Blue Waters Conference. Madison, WI.

- Landis, G., Bolinson, B., Renz, M., Rickenbach, M., & Jackson, R. 2017. “Rotational grazing for conservation of public grasslands in Wisconsin: A case study in adaptive co-management.” Poster. Ecological Society of America Annual Meeting. Poster. Portland, OR.

- Landis, G., Asper, S., Bolinson, C., Grace, J. 2017. “Unexpected Allies: Partnerships in Grazing and Grassland Management.” Roundtable. GrassWorks Grazing Conference. Wisconsin Dells, WI.

- Landis, G. 2016. “Adopting and evaluating ‘best practices’ for partnerships in grazing on public lands.” Presentation. American Evaluation Association Conference, Atlanta, GA.

- Landis, G. 2016. “Developing ‘best practices’ for public-private grazing partnerships on Wisconsin’s grasslands.” Panel. Food, Environment, and Agricultural Studies Symposium, St. Paul, MN.

Project Outcomes

This project supported the development and expansion of rotational grazing as a land management tool in Wisconsin. The WDNR has used the data collected and relationships with UW-Madison researchers to select 5 new sites for grazing management in 2018 and 2019 (Grazing Site Survey Template) , and is in the process of hiring a full-time, state-wide grazing specialist to direct grazing land management and partnerships across Wisconsin.

The UW-Madison research group is in the process of developing a set of decision support tools for grazing, a set of financial and agronomic calculators to improve grazing education and facilitate future grazing contracts. The need for a set of decision support tools was identified through interviews and meetings with land managers and graziers, and the research group is continuing to collaborate with these groups to develop tools to meet those needs. Grazing research is continuing through UW-Madison graduate students at the grazed wildlife areas, and a number of grant proposals have been submitted to increase collaborations and expand the work with graziers and grazing specialists.

In addition to the conferences and meetings listed in the outreach section, the work will be presented at the Our Farms, Our Future National SARE conference in St. Louis and a Wisconsin grazing training in July 2018. Two manuscripts from this project are in prep for submission for publication at the Journal of Environmental Management and Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Environment. We hope to continue building the collaboration with graduate students, graziers and land managers, refining the practices of the project and making the research results available and accessible for grassland management, environmental policy and planning, and conservation education.

We developed a better understanding of the meaning and mechanics of successful grazing management and research partnerships.We will use this complex understanding of successful grazing management to evaluate pilot projects and prioritize new research areas for partnerships in conservation agriculture. The baseline vegetation and soils data collected across 5 grassland wildlife areas will contribute to future understanding of grazing and serve additional monitoring.The interviews revealed a more nuanced definition of successful grazing management, using partnerships as a way to manage habitat and provide land access for graziers, to improve economic opportunities for grassfed livestock and conservation, and to build connections between agricultural communities and state land management agencies.