Final report for GNC16-233

Project Information

Our research’s long-term goals are to demonstrate the value of cavity nesting bees for urban crop pollination, and examine how to manage urban habitats to support productive bee communities. We will progress towards these general long term goals through two learning outcomes and one action outcome. By the end of our project, we will help 60-100 urban farmers and gardeners learn (1) what crop and non-crop floral resources bees are using on urban farms and (2) if planting prairie plants near nesting sites improves bee reproductive success. Likewise, we will encourage these urban farmers to take action and modify their farm management practices to incorporate pollinator habitat on their farms (Action Outcome).

In order to achieve our learning and action outcomes we will conduct pollinator workshops, field days in urban farms and pocket prairies, extension factsheets, scientific publications, and partner with a farming advisory committee of six Cleveland urban farmers, who will be compensated for their time and participation. Educating our advisory committee and other urban farmers about pollinator communities within urban agroecosystems will provide these growers with the information they need to make sustainable decisions.

Cooperators

Research

Field Work:

- We established trap nests at nine urban farms and ten pocket prairies in Cleveland, OH on April 5, 2017.

- Trap nests consisted of a PVC pipe filled with thirty cardboard nesting straws (15 cm long) at three diameters (4,6,8 mm) and provided supplementary bee nesting cavities.

- Throughout the 2017 and 2018 summers (April-July), we visited each nest biweekly, removed all occupied straws, and replaced them with new straws.

- We also completed a floral inventory and measured bloom abundance and area along four 10 m transects, arraying out from each nest in cardinal directions.

- Removed straws were then X-rayed to confirm nesting, and the pollen was dissected from the straws for further molecular analysis.

Pollen Molecular Work:

- Pollen samples were homogenized and then lysed with a bead beater machine. We extracted DNA from all of our pollen samples using a phenol chloroform method.

- We then used a multi-locus, consensus based approach to pollen metabarcoding-- this means we amplified our pollen DNA at three molecular markers (ITS2, trnl, rbcl) and can estimate a plant species' relative quantity within a pollen ball by calculating the median proportion of sequencing reads across all markers. Only species identified by 2/3 markers will be considered true positives.

- For each sample, we conducted 9 PCR reactions (we use a three step process for each molecular marker-- See Richardson et al. 2015 for details) in order to prepare our DNA libraries for sequencing.

-

Richardson, R. T., C. Lin, J. O. Quijia, N. S. Riusech, K. Goodell, and R. M. Johnson. 2015. Rank-based characterization of pollen assemblages collected by honey bees using a multi-locus metabarcoding approach. Appl. Plant Sci. 3: 1500043.

-

- Next generation Illumina sequencing took place in March 2020 through Ohio State University's Molecular and Cellular Imaging Center (MCIC).

- A UTAX algorithm compared sequencing reads to known sequences in the NCBI database and identified plant species. Only species identified by 2/3 markers were considered true positives.

Analysis and Future Work:

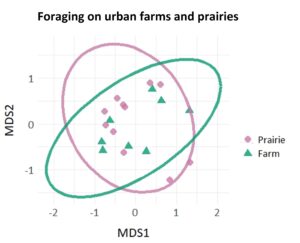

We report preliminary, qualitative results below, including a comparison of pollen choices in prairie and farm habitats with a non-metric multidimensional scaled analysis (NMDS). This analysis evaluates if the urban bees foraged on different plant communities when nesting in these unique habitats and at different time points during the sampling season. Likewise, we also report a list of urban crops which were foraged on by bees throughout our project.

In the future, we plan to complete linear regression models to determine what local habitat and landscape factors influence bee's foraging breadth and the proportion of crop pollen visited.

DNA from collected larvae was sent to the Canadian Centre of DNA Barcoding (CCDB) for further species identifications and we are awaiting results from this analysis.

2017: ![]()

- We collected 111 bee nests from 6 urban farms and 8 urban prairies in Cleveland, OH.

- All bee nests were X-rayed and then pollen/bees were dissected

- A total of 559 larvae were counted from our collected nests.

- DNA extraction is underway.

2018:

- Bee nesting abundances were pretty poor in 2018, but we still collected an additional 36 nests containing 180 bee larvae.

- (That's a 68% decrease in nest abundances although there were still 5 bees per nest, on average.)

- We pooled pollen from each nest and have completed DNA extraction for all of our 2017-18 samples.

- We are 2/3 of the way through our sequencing preparation and are hoping to send our samples out this Spring!

2019:

- After some trouble shooting, we completed our pollen DNA sequencing!

- We detected 130 plant genera foraged on by bees, although only 30 genera were present in amounts >0.25% of all collected pollen.

- Our top 10 foraged on plants were as follows:

Genus

Common Name

Amount %

Frequency

Trifolium spp.

Clover

51.3% 100.0% Lotus spp.

Birds foot trefoil

11.0% 93.2% Securigera spp.

Crown vetch

11.0% 93.2% Cichorium spp.

Chicory

3.3% 63.2% Vicia spp.

Hairy vetch

3.1% 41.4% Taraxacum spp.

Dandelion

2.5% 49.6% Rubus spp.

Raspberry

1.5% 19.5% Malva spp.

Mallow

1.2% 50.4% Potentilla spp.

Cinquefoil

1.0% 34.6% Zinnia spp.

Zinnia

0.9% 3.0%

NMDS Ordination Plot of Pollen Communities

- Our comparison of bee foraging on urban farms and prairies to-date showed no significant difference in the plant community visited by nesting bees (p>0.05)

- This means that urban cavity nesting bees visit similar plants within the urban landscape, regardless of whether the bees are nesting at a farm or prairie habitat.

- In general, exotic Fabaceae weeds dominated each pollen sample and the top 3 species were consistent and independent of nesting habitat location.

Pollen Collected From Urban Farms

- Crop pollen only accounted for an estimated ~2% of all bee collected pollen

- We identified at least 27 species which were likely foraged upon from nearby gardens. Species inferences were based off of ITS2 sequence alignments of 98 percent identity or higher.

|

Species |

Common Name |

|

Amelanchier canadensis |

Serviceberry |

|

Allium cepa |

Onion |

|

Asparagus officinalis |

Asparagus |

|

Anethum graveolens |

Dill |

|

Borago officinalis |

Borage |

|

Brassica napus, oleracea and rapa |

Cruciferous vegetables |

|

Coriandrum sativum |

Coriander and cilantro |

|

Cucumis melo |

Melons |

|

Daucus carota |

Carrots |

|

Fagopyrum esculentum |

Buckwheat |

|

Foeniculum vulgare |

Fennel |

|

Assorted Fragaria species |

Strawberries |

|

Glycine max |

Soybeans |

|

Helianthus annuus |

Sunflower |

|

Malus domestica |

Apple |

|

Mentha spicata |

Spearmint |

|

Origanum majorana, vulgare |

Marjoram and oregano |

|

Petroselinum crispum |

Parsley |

|

Phaseolus vulgaris |

Common bean |

|

Physalis philadelphica |

Tomatillo |

|

Rheum rhabarbarum |

Rhubarb |

|

Assorted Rubus species |

Blackberries, raspberries and dewberries |

|

Sambucus canadensis |

Elderberry |

|

Solanum aethiopicum |

Ethiopian eggplant |

|

Solanum lycopersicum |

Tomato |

|

Spinacia oleracea |

Spinach |

|

Zea mays |

Maize |

Preliminary Conclusions

- Most of the top foraged on plants were non-native spontaneous vegetation, or common urban weeds, in the Fabaceae family (i.e. legumes). However, we have yet to connect which bee species accounted for particular foraging choices. This indicates that it might be beneficial to allow weeds, especially red clover, to grow on urban farms as these non-native plants support bee reproduction.

- Raspberries and Zinnias were frequent forage on farms, whereas other planted crops or ornamental flowers were not found in high abundances within our bee nest provisions. This suggests that urban cavity nesting bees are likely providing pollination services to urban raspberry crops and that zinnias and raspberries may be appropriate planting recommendations for future on-farm pollinator plantings.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

2017: In conjunction with the Cleveland Botanical Garden's Green Corps and the Ohio Ecological Food and Farming Association, Katie and her mentored undergraduate co-presented to an estimated 100-115 urban residents about their research on urban farms and its potential to influence urban pollinators.

Rodney and Katie also co-conducted two separate field days with 47 youth who were employed as urban farmers through Green Corps. On these field days they broadly taught youth farmers about insects, and then familiarized them with urban pollinators and their role in pollinating crops.

Katie also traveled to Uppsala, Sweden and presented her research (to-date) to a collaborator's group at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU).

2018: We continued our collaboration with Cleveland's Green Corps of youth urban farmers this year. We developed and ran a workshop about urban biodiversity on the farm. As part of workshop, we taught this year's cohort of youth farmers about insect taxonomy, convinced them to try both insect catching and pinning, and facilitated a scavenger hunt about common plants and insects that occur on urban farms. Involved in this outreach event were Denisha Parker (another NCR SARE recipient) and our two mentored undergraduates, who helped design our workshop stations.

Both Rodney and Katie presented about their research at the annual Entomological Society of America's meeting in Vancouver, BC, Canada in November 2018. Moreover, Rodney successfully defended his dissertation in December and has now accepted a Post-Doc position at York University in Toronto, Canada!

2019: We collaborated with the Cleveland Museum of Natural History to host "From Blight to Bright: Reimagining vacant land to support people and biodiversity in cities"-- a day-long field tour/workshop discussing vacant lot restoration.

We rented a bus and brought ~50 participants on a tour of a 1) vacant lot, 2) pocket prairie, and 3) urban farm. At each site, we discussed research findings that the Gardiner Laboratory has yielded over the past 5 years and their importance.The tour then concluded at the museum with four seminar presentations about 1) urban conservation, 2) Summer Sprout gardening initiatives, 3) the process of prairie construction, and the 4) value of urban trees.

Due to conference coronavirus cancellations, we have not presented research results in person to-date. However, Katie participated in two virtual conferences this spring, 1) Ohio State's College of Food, Agriculture, and Environmental Studies research conference, and 2) the North Central branch of the Entomological Society annual meeting, where she discussed bee foraging in urban pocket prairies.

2020: In May, Rodney accepted a faculty position at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, where he will continue to apply metagenetic techniques to advance pollinator health research.

Project Outcomes

Our project will contribute to urban agriculture sustainability by elucidating which floral resources are common food sources for important pollinators. We found that weeds (non-native spontaneous vegetation) provide much of the pollen fed to developing bees and thus farmers should consider a relaxed approach to weed management in order to support bee foraging. Especially since planted crops do not always provide continuous blooms, reduced mowing and weeding may help extend food resources for nesting bees. Economically, reduced management may be beneficial to farmers as workers will have more time for crop cultivation and fewer equipment expenses for mowing or herbiciding. Likewise, with better pollination services, crops are expected to increase in quality and quantity-- hopefully benefiting farms financially.

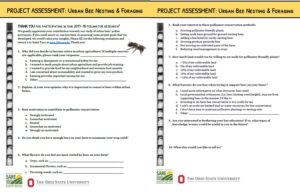

We assessed partnering farmer's attitude towards and awareness of urban bee conservation through a Project Assessment survey.

In this survey, we asked farmers to describe their motivation to work in urban agriculture, their interest in on-farm pollinator conservation, and barriers to implementing pollinator conservation practices.

Results from this survey indicated that growers were:

- Motivated to urban farm for various reasons including job training, income, interest in sustainability and food security

- Somewhat or Strongly motivated to conserve urban pollinators

- Generally willing to reserve <5% of their land for bees. Although 2 participants listed 10% and 15%

- Time and city ordinances were the most common barriers to urban bee conservation