Final report for GNC19-291

Project Information

A Comparative Analysis of Iowa Watershed Organizations: Structure, Function, and Social Infrastructure.

In 2013, Iowa released the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy (INRS) as a response to the hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico, acknowledging the role that agriculturally dominant states play in water quality issues downstream. The INRS is reliant on voluntary implementation of conservation practices to mitigate field runoff. Such implementation can be difficult to achieve at the watershed scale, and the INRS in particular has received criticism for its slow pace of implementation. Social infrastructure—defined succinctly as how communities come together to solve problems—is critical to this large-scale, voluntary implementation. To better understand this critical component, I conducted a comparative analysis of five lowa watershed organizations using qualitative methods, primarily stakeholder interviews, to gain first-hand accounts of how social infrastructure presents itself in these organizations, and how this in turn both affects and is affected by the groups' structure and function. From the analysis, I was able to create two concept maps of social infrastructure, as well as highlight the challenges and successes these organizations have had, including how the watershed organizations have helped to define what it means to be a community of the watershed.

Three of the five participating organizations were Watershed Management Authorities (WMAs), which operate through voluntary, intergovernmental agreements that conduct local watershed planning across multiple jurisdictions. The three participating WMAs were the North Raccoon River WMA, the Boone River WMA, and the Turkey River WMA. The remaining two organizations have more direct farmer involvement and leadership, as well as a less formal structure. These two organizations were the Black Hawk Creek Water and Soil Coalition and the Rock Creek Watershed Project. The research relied on a grounded theory approach that used matrix coding queries to uncover themes across interviews, as well as in the content analysis of watershed plans and other organizational documents. Due to the qualitative nature of the study, results are not generalizable; however, each group that participated in the study is receiving an individualized report that focuses on particular highlights from that group's interviews.

The study also resulted in actionable recommendations for the participating organizations, and other, similar organizations in Iowa. Recommendations include that:

- WMAs consider a new organizational structure, as the boards consist of many locally elected officials, compromising the longevity of the group. More citizen and farmer champions could also be useful in diminishing turnover, as there is presently not a formal seat on the board for farmers who are not also a part of local government, a Soil and Water District Commissioner, or appointed via a local government entity.

- WMAs should seek better collaboration amongst themselves and other watershed groups in order to be a voice for legislation for additional funding, as it is apparent this is needed to pay for long-term coordinators who can build trusting relationships with farmers.

- There are opportunities to better integrate watershed plans with community and economic development. Watershed plans currently seem divorced from other planning efforts, particularly as it relates to local economics. Economic development that is better tied to businesses that can assist in sustainable agriculture and conservation practices can better support the goals of the watershed plans and the work that farmers are being asked to do.

Due to the nature of the study, an educational approach was not included, nor were there recommendations for farmer adoption actions. From the recommendations to the participating organizations, however, it is hoped that greater farmer involvement in the watershed initiatives can be fostered and that watershed projects will be seriously considered in economic development, particularly in rural areas.

The project contained two sets of objectives. The first set was directed by the following question: What are the most impactful elements of social infrastructure as it applies to watershed management? This question was answered through two objectives: 1) to understand how five of Iowa’s watershed management organizations are using or contributing to the social infrastructure relevant to their watershed’s scale in order to achieve their goals for water quality and flood mitigation; and 2) creating post-study concept maps that refine the understanding of social infrastructure as it applies to both WMAs and farmer-led watershed organizations in order to provide recommendations for improving Best Management Practice (BMP) adoption. The post-study concept maps that will be presented have been largely influenced by interviewees, who described components of social infrastructure as it applies to watershed management and rural communities.

The second set of objectives was directed by a separate question: How does the structure and function of watershed management organizations influence BMP implementation? The two main objectives are: 1) reveal finer detail regarding organizational structures, including catalysts of said structure; and 2) demonstrate key functions of the groups, specifically as to how they define objectives, facilitate stakeholder interaction, and collaborate both internally and externally to reach their goals.

The findings from these two sets of objectives were deeply intertwined in order to provide not only a clearer picture of the social infrastructure at work in watershed management, but also in providing actionable recommendations, with the intent of increasing voluntary BMP implementation.

Research

With the assistance of the Iowa Water Center (IWC) and the Iowa Watershed Approach (IWA), six watershed organizations in Iowa originally agreed to participate in this study. Watershed organizations were recruited based on geographic location, age of the groups, and amount of farmer involvement. For the WMAs in particular, their receipt of funding through the IWA’s Housing and Urban Development grant was also of interest. Originally, four WMAs were included in this study, with two of them being affiliated with the IWA, as I was interested in understanding if the funding had an impact on the WMAs’ functions. However, one of the IWA affiliated groups was later removed from this research due to low interest in participation.

The research follows a qualitative case study approach for the five remaining organizations, wherein detailed data is gathered through multiple sources. Qualitative data was triangulated by gathering first-hand accounts of watershed organizations and social infrastructure through one focus group with farmers and twenty-six interviews with watershed organization stakeholders, which were compared to organizational documents such as watershed plans, progress reports, and grant applications. For qualitative research, triangulation serves to validate data, corroborating themes and analysis. To better understand the groups under study, I also attended as many meetings as possible to further triangulate information gleaned from interviews and documents.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic that was declared shortly before focus groups were scheduled, nearly all interactions, including group meetings, occurred in a virtual format. Despite the virtual format of interviews and meetings, I find it unlikely that there is a discernible impact on the data collected. However, the virtual format of focus groups may have negatively impacted the number of participants. Two virtual farmer focus groups were planned, but in the end, one just had two farmers join in a discussion of social infrastructure as they experience it in their respective communities. The second focus group became more of a semi-structured interview when other participants were unable to join. Originally, farmer focus groups were envisioned as a part of the study in order to discuss the social infrastructure that may be particular to farming communities, which would help refine the concept for use in this study. Due to the low participation from these farmer focus groups, however, the information gathered was used to further triangulate findings as they relate to social infrastructure, rather than as a main source of data.

From July 2020 to November 2020, I conducted interviews with 26 stakeholders in the five organizations under study—six interviews in the North Raccoon River WMA and the Rock Creek watershed, five interviews in the Boone River and Turkey River WMAs, and four interviews from the Black Hawk Creek Water and Soil Coalition. Interviews with watershed stakeholders followed a semi-structured approach, with questions informed by the literature surrounding water quality issues, other case studies of watershed organizations, and conversations with water experts in Iowa. The semi-structured interviews allowed for the same set of questions to be used with each watershed organization under study, with natural digressions regarding the unique context of each group. Interview questions were pilot tested with a staff member from the IWC prior to reaching out to stakeholders in the groups under study, which allowed for revisions and a better understanding of how interviewees may interpret the questions.

The focus group discussion and all interviews were recorded with permission from participants. Recordings were transcribed with the help of an undergraduate research assistant certified in human subjects research by the Institutional Review Board. Transcripts were then coded in NVivo software. For the post-study concept maps that were informed by both a review of the literature and interviews, coding of the transcripts followed a grounded theory methodology, wherein the initial open coding process allows the data to guide themes and analysis. The open coding process is followed by focused coding, which delineates relationships between themes.

For themes surrounding the groups’ structures and functions, initial codes were based on the watershed management literature, with emergent themes added as codes as the process went on. I also used memoing while coding transcripts and documents to take note of possible relationships emerging in the data and link together ideas brought forth from different watershed management organizations under study.

The average interview length was 66 minutes, with the longest two being just under two hours, and the shortest lasting for 40 minutes. At least one farmer was interviewed in each group that participated. For WMAs, other interviewees included board members appointed by cities and counties. Personnel from the organizations' partnering agencies and Soil and Water Conservation District Commissioners were also interviewed in some instances. This study received exemption by Iowa State University’s Institutional Review Board for human subjects research in November 2019. All interviewees and focus group participants were informed of the voluntary nature of their participation and that any quotes used from the interviews would remain anonymous.

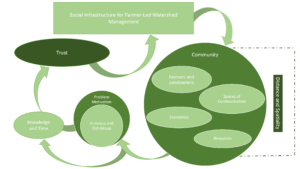

Results were measured via the strongest themes captured during the coding process, as well as from the matrix coding queries that captured multiple codes' relationship to the specific code for social infrastructure. While the point of a qualitative study such as this one is not necessarily to quantify themes, the coding of each transcript allowed similarities and differences to be found among the participating organizations, noting when a theme was particularly strong or unexpectedly absent from one group or another. At the end of this section are the two post-study concept maps demonstrating the most critical components of social infrastructure as it relates to the two different types of watershed organizations that participated in this study--WMAs and farmer-led groups. From these concept maps and an analysis of the themes surrounding the organizations' structure and function, the following findings emerged:

- Spatial effects have an impact on group structure, outreach, and implementation. Spatiality was identified during coding as an important theme due to the influence that distance has on communication and collaboration. Spatiality can create “hotbeds” of activity, where it is difficult to get wide implementation of Best Management Practices (BMPs), creating In-Groups and Out-Groups in the same watershed.

- Watershed management can positively impact local economies, and vice versa. The presence of a local cover crop seed dealer in one farmer-led group (the Rock Creek) was mentioned by all six interviewees as a positive in reaching additional farmers and creating a knowledge community. Additionally, one interviewee specifically mentioned the impact that farming practices such as cover cropping and no-till can have on the local economy, and it is worth quoting them in full:

- "One thing that has really helped us as beginning farmers, and I think a lot of people around here [...], as other people want to try some of these practices--I guess, for example, when, when we first started farming, we bought a, a grain drill that we could seed cover crops with, and we do a lot of custom cover crop seeding for people because they don't want to go out and buy the equipment. And that has helped us, you know, make some extra income off of, you know, outside of just our farmland. And that's been the case for [...] a lot of things, it's-- it's led to more people growing, like small grains locally, and so we're, you know, we seed all grains for people to grow for cover crop seed. And then, you know, we're, we're hiring somebody to bale the straw off they have to sell to people within the area. So it's kind of just added a little supply chain back into the local economy that, that was kind of disappearing pretty fast. Um--cover crop business that is buying and selling things locally that wasn't here before, and we got people that are, that are doing a lot of custom strip till, or planting or, you know, seeding like we are. We're buying more parts and we're exchanging money locally. So I think it's just--it's been a way to help stimulate the local economy in a way that just corn and soybeans farmed conventionally weren't doing."

- This project indicates, however, that there is likely still more work to be done in amplifying watershed plans through intentional economic development, as one farmer interviewee mentioned that between wet weather and difficulty hiring a contractor, they had waited four years for a bioreactor to be installed in one of their fields.

- All three WMAs that participated cited board turnover and disengagement as an issue in reaching the necessary quorum to vote on agenda items. A lack of funding was also cited as creating disengagement since WMAs cover multiple jurisdictions, and what funding is received is often earmarked through grants for specific parts of the watershed that do not involve many board members.

- WMAs have a greater need to “pay for” social infrastructure through funded coordinator positions that have longevity, so as to build trust with farmers and landowners.

- WMAs can be a vehicle for accepting controversy, providing needed space to discuss issues related to nutrient reduction goals and flood mitigation. In the Turkey River WMA specifically, which was the oldest WMA participating in this research, interviewees commented that they felt the WMA helped to erase artificial boundaries between upstream and downstream, farmer and non-farmer:

- “I mean, simply that there, you know, from the aspect of the watershed, that a boundary is nothing more than a line on a map. It's meaningless. And working with these towns, I mean, we've done some—you know, town's got a lot of flooding, and we've been involved with, um, watershed easement buyouts, [Wetlands Reserve Program] projects, emergency watershed projects. And most of those are right next to a community some place, so, you know, merging that agricultural community in with what's happening in town. You know, and these people are, these producers who live outside of town that [unintelligible] like, ‘Hey, that's our town too.’"

- WMAs appear more reliant on external partners for both funding and knowledge generation, possibly undermining internal collaboration.

From the aforementioned recommendations and findings, it is clear that the social infrastructure of watershed management and the organizational structure and function of these groups are intertwined in a feedback loop. Below are the two concept maps of social infrastructure as it exists in the different types of organizations that participated in this study--WMAs and farmer-led groups. These concept maps show the most impactful elements of social infrastructure and how different components appear to feed into one another. For both concept maps, distance and spatiality play a mediating role in how the various watershed community components relate to one another. The largest difference between the concept maps for WMAs and for farmer-led groups is that external partners and funding played a much larger role for the WMAs' social infrastructure, while economics played a key role in one farmer-led group and could be an important component to consider for other, similar organizations.

It can be useful to imagine how each recommendation listed in the project summary—if taken under advisement—would shift the social infrastructure of the organizations under study. If the WMAs adjust their structure to account for turnover and disengagement, this could advance problem motivation due to action items being voted on in a timely manner, building momentum and leading to greater collaboration amongst the stakeholders that have demonstrated an interest in seeing the goals through. Greater levels of collaboration could lead to additional project implementation, and thereby greater visibility of the work the WMA does. Having the WMA as a visible presence could enhance farmer and landowner trust in the organization, making the overall social infrastructure of the group more effective as it includes a greater amount of contact with community members at the watershed-scale.

Should WMAs successfully collaborate with the legislature and gain a stable funding mechanism, this would affect the organizations’ social infrastructure by freeing up knowledge and time—both within the groups and outside of them—that is otherwise spent seeking grant funding. A success in this regard would not only impact the social infrastructure of WMAs, but also that of farmer-led groups. Though a stable funding mechanism coming from the state does not represent a collective investment from the community that other researchers found to be necessary to social infrastructure, at the watershed-scale, the water quality and flooding problems the community is addressing are too costly—in the millions of dollars—to be covered entirely by local sources. Were stable funding to be achieved, additional outreach could be conducted and technical assistance provided, once again enhancing the level of trust present at the watershed-scale..

The last recommendation from the study—integrating watershed plans with local economic development—would likely be the most influential on any watershed management organization’s social infrastructure. If this were shown to be a successful way to engage additional farmers and landowners, the resources present in the watershed-scale social infrastructure would become more nuanced. Resources may include local support systems for BMP implementation, as well as local, collective investment that could reduce risk to farmers and landowners. Local businesses in the watershed that support BMP implementation would add additional spaces of communication to the organizations’ social infrastructure, as well as additional sources of knowledge. Of the recommendations provided here, this is the most likely to suffer from the spatial effects of social infrastructure, whereby it is possible for “hotbeds” of activity to develop in areas that are better connected to these local businesses. By involving local economies with the watershed management organizations, however, hopefully the effect of spatiality could be attenuated.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

The research that I conducted for this grant not only formed the basis for my Master's thesis, but I have also been able to create five individualized reports for the five watershed groups that participated. These reports summarize the findings of the entirety of the study while also focusing on specific recommendations for individual groups and the specific challenges or successes that interviewees highlighted for their respective groups. While each of the five participating groups will be sent a copy of my completed Master's thesis, these individual reports allow the organizations to digest information that is mainly pertinent to them.

In April 2021, I participated in the Iowa Water Conference, and my poster based on this research was accepted for exhibition in their virtual poster hall. I was able to speak to the student poster contest judges about my study, which I feel was important to include in the poster hall, as much of the other research was quantitative, while mine was qualitative, yet included what I feel are realistic recommendations for watershed groups in Iowa to consider.

This summer, though I have graduated from my Masters' programs, I will also be working with a former professor to adapt one of my thesis chapters into a journal article for publication in the hopes that the important perspectives from the study's interviewees will reach a wider audience.

Project Outcomes

My project will affect economic sustainability through an increased awareness of the local supports and local business development that can assist farmers in taking up new conservation practices and adopting them for the long-term. Studies have clearly shown that conservation practices can improve farm profitability by reducing field maintenance costs and crop inputs, and through more efficient use of marginal/unprofitable areas within fields. This project demonstrates the need for steady funding for watershed coordinators, which will also help watershed organizations become more adept at engaging stakeholders in ways that efficiently link farmers to needed technical and financial support. Additionally, this project sheds light on the desire for markets to expand beyond corn and soy, which would allow farmers in the North Central region to diversify income sources.

Environmental sustainability will be impacted by this project through its examination of how to expand voluntary implementation of conservation practices. Watershed organizations can learn from, adopt, or modify their outreach and structure so they can more fully engage their stakeholders in the actions required to meet environmental goals at spatial and temporal scales that matter to society, as every watershed organization that took part in this study was operating across multiple jurisdictions. Research on conservation practices designed for water quality goals has demonstrated that such management concomitantly improves soil health, increases biodiversity, and enhances ecosystem resiliency.

Social sustainability will be impacted by this project through its first-hand accounts of how social infrastructure can be fostered by watershed organizations, recommending in particular that watershed organizations without a formal, and intentional, way for farmers to be involved with decision-making seriously reconsider their organizational structure. As one quote included in this report from an interviewee makes clear, watershed organizations focusing on multiple jurisdictions within the watershed-scale can erase the artificial boundaries between farming and non-farming communities, one county or city and another. As rural populations continue to decline in the Midwest, connectivity and social ties are increasingly important in these areas. Recognition that environmental challenges can be opportunities for stakeholders to collectively improve social, economic, and ecosystem health, benefits society as a whole.

During this project, I feel that my knowledge increased in regard to the nuances among farmers practicing sustainable agriculture, as well as my knowledge of the obstacles that farmers see in better implementing sustainable practices. The farmers I interviewed were of course self-selecting to a certain extent, in that they were already interested in practices that would improve water quality and soil health, as well as being active in their local watershed group. However, it was interesting to hear the range of ideas they had for the future of row-crop production. Perspectives ranged from wanting to more narrowly target best practices, such as cover crops, to experimenting with relay cropping, to questioning the status quo of corn and soybeans in Iowa. Additionally, a few farmers mentioned that the markets do not exist to support farmers who wish to move away from corn and soy rotations, despite additional rotations proving beneficial for soil health and pest management.

While it can be easy when speaking hypothetically about the future of sustainable agriculture to list what practices or crops could be beneficial, farmer interviews dispel the idea that any group of farmers is homogenous in their viewpoints. Furthermore, mentions from interviewees of the current corn and soy markets being dominant did not change my attitude on sustainable agriculture; rather, it amplified the idea that widespread adoption of sustainable agricultural practices will require more systemic change beyond the local or regional levels.

There are two main recommendations for future study that I believe are important to point out. First, it was outside of the scope of my study to complete an in-depth look at watershed management funding mechanisms in different contexts. There is large potential for researchers to continue analyzing what other mechanisms states and entities have used in contexts that are outside of Iowa and also relying on voluntary adoption of Best Management Practices (BMPs). States in the Mississippi River Basin appear to be working separately on issues of water quality, and it could be useful to better understand how these states could better cooperate to increase the mitigation of nutrients flowing to the Gulf of Mexico, comparing how such efforts are ultimately funded. Secondly, future research into the economic benefits of watershed management and integrating local economies into watershed plans could also provide valuable insight for both the fields of Sustainable Agriculture and Community and Regional Planning. An interdisciplinary perspective on this particular point would be beneficial for widening the scope of research and further legitimizing the issue.