Final report for GNC20-312

Project Information

While soil health is proven to have wide-ranging benefits and is of increasing interest to farmers and agricultural stakeholders, there is still relatively low adoption of soil health practices (e.g. cover crops, no-till, crop rotations) on Midwest row crop farms. We predict that one reason for limited adoption is that soil health is an abstract idea with long-term returns, and that farmers may lack concrete strategies by which to improve and evaluate soil health. Most studies investigating farmers’ perceptions either focus on a specific practice, rather than soil health more broadly, or use a single method, which makes it challenging to describe both the breadth and depth of farmers’ engagement with soil health. To address this gap, we used surveys, interviews, and mental models to describe how Michigan farmers understand, evaluate, and manage for soil health. We found that Michigan farmers believe in the benefits of soil health, identify many properties that impact it, and are particularly focused on its impact on yield and water management. Many Michigan farmers believe they are taking steps to improve the health of the soils they farm, which was reflected in their per use of no-till and cover crops, as well as other practices. Despite the broad belief and value for soil health, it can be challenging for farmers to link soil health to management decisions. Farmers primarily evaluated soil health through traditional agronomic soil tests, yield, and qualitative indicators (e.g., yield, crop coloration, soil texture), yet several farmers also described how comparisons across soil types can be problematic and, thus, make it challenging to connect soil health to management. This study emphasizes a need for regionally-defined soil health benchmarks that can guide management decisions, as well as increased research about how management affects particular soil properties, rather than “soil health” alone.

The three learning outcomes for this project included: 1) increase the academic community’s knowledge of how farmers’ soil health mental models inform their management decisions, 2) increase awareness and knowledge of farmer mental models and resources for agricultural advisors, and 3) simplify the complicated ‘soil health’ concept for farmers in the eastern Midwest corn belt. This project also had two primary action outcomes: 1) agricultural advisors will improve their practices by incorporating farmer soil health mental models into their training and outreach activities and 2) we will help enhance networks between agricultural stakeholders in southwest Michigan.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

Research

Research: We used mixed-approach methods with surveys, mental-modeling workbook, and phone surveys to evaluate how Michigan farmers think about and use soil health practices. To stay in accordance with COVID regulations, we shifted our originally planned in-person interviews to phone interviews.

Surveys were sent to >1,000 Michigan farmers as part of Michigan State University’s (MSU) Farmer Panel Survey. From this group of participants, we selected 20 farmers for follow-up interviews. We selected 10 farmers that have previously used cover crops and 10 farmers that do not use cover crops to increase the variation in our responses and understanding about soil health.

We used a hands-on workbook to help farmers illustrate their own soil health mental models, including what factors they think most affect soil health. The workbooks were completed by the farmer before the interview, mailed back to the researchers, copied, and returned to the farmers to guide the 1-hour phone interview. During the interview, we discussed how they filled out the soil health workbook and gleaned information about what terms farmers most associate with “crop productivity” and “soil health”. The interview and workbook responses will helped us understand how farmers conceptualize soil health, as well as what challenges prevent them from adopting soil health practices. This data guided a workshop with agricultural advisors, focused on discussing tools for promoting soil health practices.

Outreach/On-Farm Research:

We hosted two workshops and conducted 22 on-farm soil health sampling efforts that aimed to simplify the concept of soil health for Michigan farmers and identify needs for future soil health efforts in Michigan.

First, the “Diggin’ Into Soil Health” workshop, held on June 29th, 2022 at the Michigan State University W.K. Kellogg Biological Station included 33 agricultural advisors, agricultural researchers, and Michigan farmers. Participants represented many organizations, including USDA Farm Service Agency, Soil Water Conservation Districts, Michigan Agricultural Advancement, Michigan Agriculture Environmental Assurance Program, Natural Resources Conservation Service, The Nature Conservancy, National Wildlife Federation, Michigan Environmental Council, and independent crop consultants. There were four main activities during the workshop: 1) a mental modelling activity to help participants consider how their unique experiences and knowledge inform their understanding of soil health; 2) a research presentation sharing data from surveys and interviews with Michigan farmers about their perceptions of soil health; 3) a farmer panel to better understand producer needs for soil health programing and monitoring; and 4) a group discussion to identify gaps, opportunities, and next steps for soil health programming and action. A summary report of the day's findings was circulated to all meeting participants. A survey at the end of the workshop revealed that our programming was successful, and that nearly all participants felt they learned more about their own perceptions of soil health (85%) and also about farmers' understandings of soil health (95%). Every participant said that they would be interested in attending similar events in the future.

Next, in the summers of 2022 and 2023, we continued this project and used on-farm soil testing to simplify the concept of soil health to local farmers. Twelve of the 20 farmers that participated in the interviews sent soil samples to Dr. Christine Sprunger’s lab for soil health analyses. The farmers received a report of their soil health results. Many shared that they wished they could have more informative sampling, for instance by sampling areas that they know are productive vs. more challenging. To address these requests, in Spring 2023, we worked with 10 of these farmers to provide additional soil health tests of their fields, with a specific focus on sampling areas they view as more or less healthy (often related to yield). The tests included a “soil my undies” visual exploration of soil health in poor and healthy areas of their fields, as well as quantitative lab assays that assessed the physical, chemical, and biological soil properties. The results will be shared with the farmers and hopefully used to guide the farmers’ soil health knowledge and management decisions.

Finally, these on-farm conversations informed a small, half-day workshop focused on soil health action planning at Michigan State. The meeting included eight participants working on soil health outreach or research within MSU Extension or the Kellogg Biological Station Long-Term Agroecosystem Research site. The goal of the meeting was to identify how can we make soil health useful on Michigan farms (linked to outcomes, incentive for adoption), and to specifically achieve the following outcomes: 1) list current and on-going soil health efforts within MSU Extension and KBS; 2) identify gaps and needs in our approach; 3) vision and next steps for Michigan soil health action plan. We envision that this initial effort will motivate larger conversations with other local groups also focused on improving soil health and supporting farmers throughout the state.

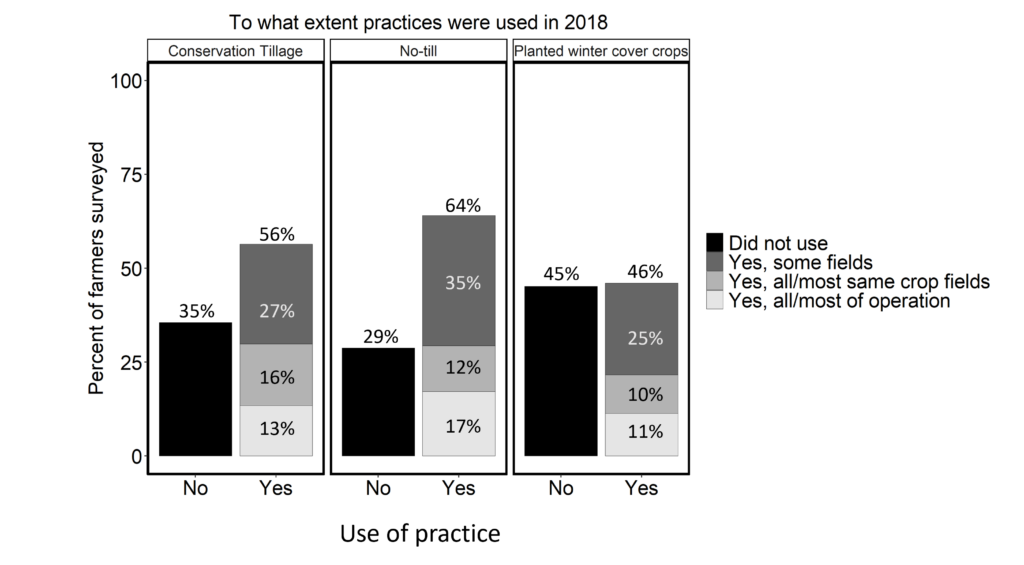

With survey data from 479 Michigan Farmers in 2018, we learned that >45% of Michigan farmers are using cover crops, no-till, and conservation tillage on at least some fields on their operation. Winter cover crops had the lowest adoption, with 46% of farmers not using the practice (Figure 1).

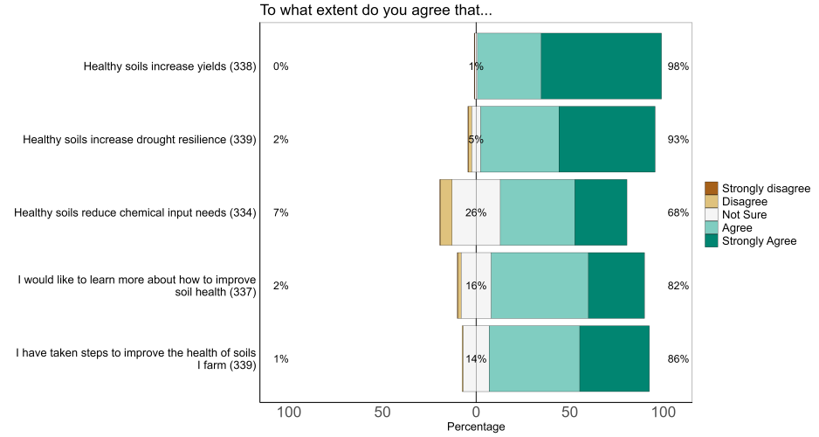

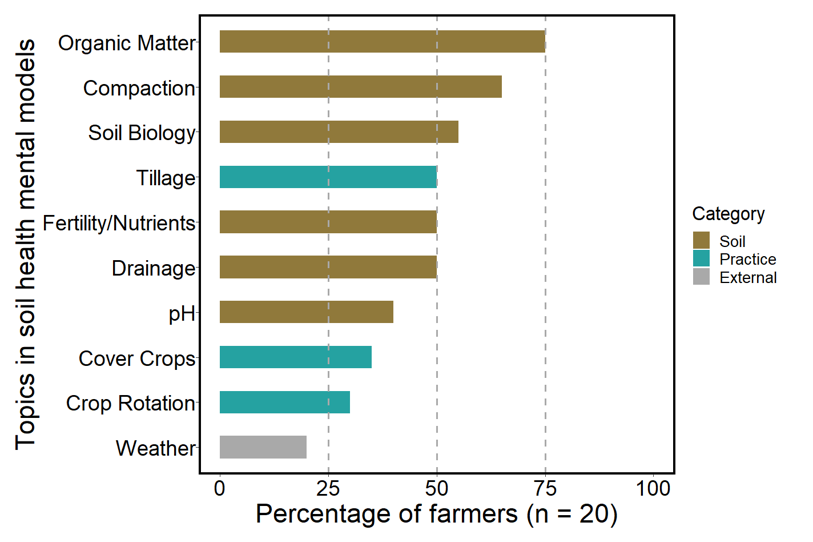

Even though adoption of some soil health practices is low, we found that over 90% of Michigan farmers have confidence that healthy soils can increase yields and drought resilience (Figure 2). Importantly, most (81%) of farmers want to learn more about how to improve soil health, and 86% share that they have taken steps to improve soil health on their farms. This shows that there is a lot of opportunity to help farmers improve their soil health management efforts. Indeed, in the mental model activities and interviews, farmers identified many soil properties that can impact soil health, but there was less agreement about what practices directly affect soil health. For instance, organic matter, compaction, and soil biology were the topics most frequently mentioned by farmers to impact soil health. Cover crops and tillage were the most frequently mentioned practices, specifically when considering how soil health management can impact their ability to respond to water challenges.“We try to manage too much rain with [tile] drainage, [but during] the drought, the less tillage and cover crops actually helped us” (row crop farmer in SW Michigan).

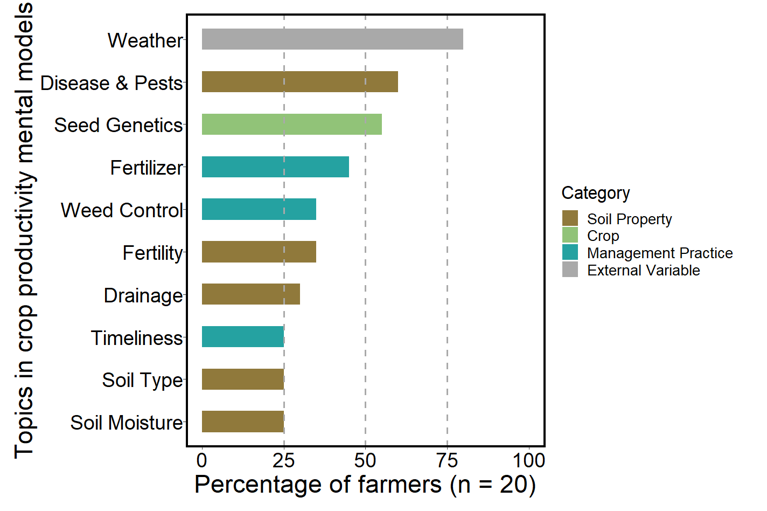

Finally, the interview and mental model data also revealed that there are many complex factors that farmers consider when managing cash crop productivity, and that soil health is just one aspect. When asked which terms most affect crop productivity, soil health was only mentioned by 3 of 20 farmers. They did, however, mention terms associated with soil health, including fertility, soil type, and compaction. Weather and pest pressure were the top factors farmers considered when thinking about crop productivity (Figure 4). Because resilience to weather events (e.g. drought and flooding) and disease pressure can be influenced by soil health, this may present an opportunity for educators to emphasize these connections when discussing the importance of soil health management on-farm.

############## Results from Workshops

Conversations during the "Diggin into Soil Health" workshop led to several key recommendations that could help farmers better manage for soil health, including suggestions for how to improve soil health tests and their translation to management, engagement and research, and policy and programming efforts. The detailed recommendations Follow:

Recommended changes for soil health tests & improved translation to management

- Couple quantitative soil health assessments with agronomic and nutrient tests that farmers already receive. Farmers are familiar with soil nutrient test results, and would like to know how other indicators of soil health (e.g. biological soil health) relate.

- Link soil health tests to farmers’ perceptions and experiences of soil health on their fields to better inform management decisions. For example, comparing the soil health of high and low producing fields, rather than “one-off” tests from different sites on their operation.

- Provide a diagram that describes each soil property and indicator of soil health, with guided recommendations summarized by soil type of how they could be improved with targeted management. On its own, soil health was considered too broad to be useful for guiding specific management practices.

Recommended opportunities for engagement & research to aid in farmers’ management of soil health

- Provide farmers with one-on-one advising and on-the-ground help to evaluate soil health and make guided, field-specific recommendations.

- Offer farmer-to-farmer exchanges to discuss soil health management efforts. Farmers want to hear from their peers who have successfully implemented a practice before seeking input from agencies or advisors.

- Engage with advisors prescribing crop fertility plans so they better understand the role soil health plays in crop health and production and how synthetic fertilizers interact with soil health.

Recommended opportunities to improve policy & programs for soil health

- Inform policymakers on the challenges to evaluating and managing soil health for quantified outcomes to better allocate state funds.

- Leverage Michigan’s Soil Health Task Force to elevate the importance of soil health state-wide.

- Allocate additional funds to conservation and agricultural agencies to:

- Increase capacity for one-on-one farmer meetings and advice (field days alone are not enough for many farmers to shift management practices).

- Provide staff with more on-farm experiences, improved trainings, and in-service activities to help build farmer trust and improve recommendations.

- Increase staff benefits and compensation to reduce turnover, which can hamper building trusting relationships with farmers.

- Invest in farmers’ labor needs to implement time-sensitive soil health practices (for example, cover crops).

The Soil Health Action Planning workshop held on November 10, 2023 with eight research and Extension educators focused on making soil health useful throughout the state of Michigan.

The group identified current needs and goals for internal communication, research, and outreach that will help ensure that soil health can be useful on Michigan farms (linked to outcomes, incentive for adoption). Below we highlight several key needs identified by this group:

- Internal communication:

- Develop and circulate common language and research on soil health to educators, advisors, and researchers interfacing with farmers.

- Research:

- Establish a fee for service soil health lab

- Increase capacity for on-farm research and participation

- Increase social science capacity to understand how soil health links with farmers’ perspectives and management

- Develop an internal data repository that merges on-farm and research site efforts

- Outreach:

- Increase capacity for soil health educators across the state

- Develop farmer peer-learning opportunities for soil health

- Publicize good work of what farmers are already doing for soil health

- Incorporate locally-informed science into incentive and regulation programs (e.g. GAMPS)

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

- Webinar for the Soil Health Nexus – June 2020

I presented a webinar for a diverse group of agricultural participants with the Soil Health Nexus Digital Café. I shared preliminary results, as well as upcoming plans for the project.

- Fact sheet with preliminary results – January 2022

We circulated a 2-page factsheet with preliminary results from the interview and survey data to >1,000 farmers in Michigan with MSU’s Farmer Panel Survey.

- Workshop with agricultural advisors – June 2022

We hosted a workshop for 33 agricultural advisors from diverse sectors (Extension, Government, Environmental NGOs, SWCD, Consultants, Agribusiness) at the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station. Five farmers were compensated to participate in a farmer panel about their experiences with soil health, particularly what they think could be improved with their advisor relationships. Overall, the three main goals of the workshop were to: 1) disseminate results from my study on Michigan farmers’ perceptions of soil health, 2) discuss differences in soil health perceptions among agricultural advisors (through hands-on activities), 3) develop “tips for talking” worksheet to standardize soil health jargon among agricultural advisors, in hopes to improve advisor-farmer communication.

- Workshop summary report – Aug 2022

Conversations during the workshop led to several key recommendations that could help farmers better manage for soil health, including suggestions for how to improve soil health tests and their translation to management, engagement and research, and policy and programming efforts. We summarized these in a white page report and circulated them to workshop participants.

- Presentation at Long-Term Ecological Research program annual meeting - Sept 2022

Presented study outcomes and challenges/opportunities co-producing research with farmers at a workshop/focus group during the annual LTER meeting in Pacific Grove, CA.

- Dissertation presentation - December 2023

Results from the survey, interviews, and workshop were presented for approximately 60 individuals, largely academics during Tayler Ulbrich’s PhD Defense presentation.

- Presentation at Long-Term Ecological Research program annual meeting – September 2023

Presented study outcomes with emphasis on barriers to soil health adoption to over 100 scientists and NGO-partners at the Long-Term Agroecosystem Research Annual meeting.

- Peer reviewed publication – in progress, to be submitted by February 2023

Peer-reviewed article highlighting results from survey and interview data collection will be submitted to Journal of Soil and Water or the Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems Journal by February 2024.

Project Outcomes

Economic

Healthy soil can increase a farm’s resilience and, in turn, economic stability during periods of stress. Previous work suggests that social connections are one barrier that limits farmers’ adoption of soil health practices. Without a network of advisors and farmers that have successfully used the practices, they lack local tips and confidence in the practice. We hope that our workshops, and enhanced networks connected to the Long-Term Agroecosystem Research site at the Kellogg Biological Station will give farmers and agricultural professionals an opportunity to discuss the key challenges with adopting soil health practices. For instance, we can discuss how farmers can start to consider how soil health affects the economic benefits of crop resilience, rather than focusing on the sole metric of yield.

Environmental

By learning the terms that farmers use to define soil health, we can start to develop better outreach materials that will reach them where they are. This will help agricultural advisors and researchers develop materials with higher success at reaching farmers, with the long-term goal of increasing the adoption of soil health practices. Healthy soils have many short- and long-term environmental benefits, including improved water quality, carbon sequestration, and enhanced biodiversity. Furthermore, the on-farm soil health assessments helped farmers connect soil health properties (e.g. soil carbon, biological activity, compaction) to areas that they visually identify as having good or poor soil health. Conversations around this data can help guide farmers’ ability to understand and manage within field variability, which can have downstream environmental benefits.

Social

This project achieved social benefits to farmers by 1) identifying their needs for research and Extension services, 2) facilitating networking between farmers, agricultural advisors, and scientists, and 3) providing a longer-term connection to the Long-Term Agroecosystem Research (LTAR) project at the Kellogg Biological Station.

First, in the interviews, we asked farmers what questions they have about soil health, and these questions will be shared with MSU scientists and Extension to help ensure that research and Extension efforts are addressing the needs of local farmers. Second, we hosted two workshops and also engaged in on-farm research that facilitated networking among farmers, advisors, and scientists. These connections already led to one farmer connecting with a local MAEAP technician, and getting his farm certified. Lastly, the initial interviews and on-farm research strengthened the farmers’ connections with the Kellogg Biological Station (KBS). Five farmers that were involved in the study also participated in a field day with the KBS LTAR in September 2023. They expressed interest in being informed about the project, which seeks to co-produce meaningful and impactful research with local agricultural professionals.

We feel that improving the relationship between agricultural advisors and farmers, and connecting farmers to the research at the KBS LTAR will help increase the adoption of soil health practices which has many long-term benefits for rural communities, including improved water quality and enhanced biodiversity.

We have a better understanding of how farmers’ conceptualize and evaluate soil health. This knowledge has motivated new connections, outreach and research efforts, including:

- New survey research questions that will help differentiate the nuances’ of how farmers connect particular practices to soil properties.

- A new team of soil health researchers and Extension specialists are working to identify next steps for soil health action planning in Michigan.

- Knowledge and connections that will support the KBS Long-Term Agroecosystem Research project, which seeks to co-produce research priorities and projects with local agricultural professionals and farmers. For instance, we have a better understanding of which aspects of soil health farmers want to know about.

- Connections with farmers and MSU researchers focused on on-farm soil health tests and precision management technologies.

- Support for new graduate students who aim to build connections and outreach materials for farmers, focused on the adoption of conservation practices.

A farmer that was involved in the interviews and workshop farmer panel connected with a local MAEAP technician and, consequently, went through the process of getting his farm MAEAP certified. This same farmer later participated in our on-farm soil health sampling efforts, including a “soil my undies” project. We buried cotton underwear in his fields to see how soil health and decomposition differ between good and poor areas of the field. He later called to share that he bought two other packs of undies to bury in his field out of pure curiosity!

Regarding the 2023 soil health workshop, a local conservation district employee shared that “the farmer panel was the most useful. More events that allow farmers to provide their perspective would be great. Inviting the local representatives to hear directly from our farmers would be great.” Another participant shared “attending similar events like this I feel like is the best way to connect with others.”

Through connections made during the on-farm soil health sampling effort, a farmer participant is now talking with MSU scientists about how their research can inform his precision management technologies (e.g. variable rate applications and incorporation of prairie strips).

Five farmers that were involved in the study also participated in the KBS Long-Term Agroecosystem Research (LTAR) field day and learned about research and management opportunities for incorporating conservation management into their operations.