Progress report for GNC22-340

Project Information

Exploring the Effects of Prairie Restoration Management on Soil Microbial Carbon Storage

Integrating restored prairies into agricultural landscapes has emerged as a strategy for providing key ecosystem services like increasing biodiversity, reducing erosion and runoff, and supporting pollinator communities. These prairies can also act as valuable soil carbon sinks, though they often fall short of their carbon storage potential. The proposed work aims to help farmers maximize carbon storage on their land by examining the influence of prairie management choices on soil microbial carbon dynamics, asking how prairie size and seed mix richness influence soil microbial carbon use efficiency and what this means for total soil carbon stores. It leverages a suite of restored prairies at the Kellogg Biological Station in southwest Michigan and utilizes a novel approach to assessing carbon dynamics in restored ecosystems.

Our goals for Learning Outcomes are to increase stakeholder awareness of the benefits of establishing prairie plantings in agricultural systems, knowledge of the trade-offs associated with different prairie management techniques, and appreciation for the importance of soil microbial communities to soil carbon storage. Our goals for Action Outcomes are to increase stakeholder openness to installing prairies on their farms and to considering belowground-minded management. We will partner with the Soil Health Nexus and MiSTRIPS groups to reach local stakeholders in 2023 to assess farmer interests, questions, and concerns regarding integrating restored prairies into active farmland. In 2024, informed by these conversations, we will present the results of our work to these groups and create a decision-making tool to share with managers. We will evaluate success of our outcome goals using pre- and post-presentation surveys. We will continue to disseminate our results by submitting articles to academic and farmer-focused publications and presenting at local and national scientific conferences.

Increasing soil carbon in agricultural systems has the potential to restore soil carbon stores lost through the transition to cropland and to offset ongoing agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. This work is particularly relevant with the Conservation Reserve Program’s recent addition of extra incentives for Climate-Smart Practices, including increasing carbon sequestration. By filling a key knowledge gap in managing for maximized soil carbon storage, this work can inform climate change mitigation efforts and thus contribute to increased environmental quality and quality of life in agricultural systems and beyond.

Learning Outcomes: After presenting our results to local stakeholders and the larger scientific community, I expect both audiences will have an increased awareness of the benefits of establishing prairie plantings in agricultural systems and increased knowledge of the trade-offs associated with different prairie management techniques. I also anticipate that both audiences will have an increased appreciation for the importance of soil microbial communities to soil health – specifically, to soil carbon dynamics.

Action Outcomes: After attending our summary presentation or reading our educational materials, I anticipate land managers will have increased openness to installing prairies on their farms and increased openness to considering belowground-minded management.

Cooperators

- (Educator and Researcher)

Research

This work took place in 12 fields under conventional agricultural management (corn), 12 oldfields abandoned from agriculture, and an existing suite of 12 restored prairies at the Kellogg Biological Station in southwest Michigan. The prairies were restored from oldfields in 2015, and they range from 0.2-3.5 hectares. Each prairie is divided in half, one side planted with a 12-species seed mix (“low-richness”) and the other with a 70-species seed mix (“high-richness”). Each half-prairie and cornfield are hereafter referred to as “sites”, with 48 total sites for the project.

In August 2023, we collected fifteen 5cm soil cores to a depth of 10cm at each site. The cores were equally spaced from each other and the field edges to ensure a representative sample of the field area. Cores were composited and stored on ice until analysis. Once in the lab, samples were aseptically passed through a 2mm sieve and analyzed fresh or stored in the fridge until analysis, as appropriate. All analyses were performed in Dr. Kathryn Docherty’s lab at Western Michigan University unless otherwise noted.

I will use the data collected in this effort to address the following three research questions:

Q1: How do prairie size and planted species richness influence soil microbial carbon-use efficiency (CUE)?

Q2: How do prairie size and planted species richness influence soil carbon pools?

Q3: Do soil carbon pools co-vary with microbial CUE?

Answers to these three questions will help inform the overarching, applied question: "How do management choices influence soil microbial CUE and the potential for long-term soil carbon storage?"

We have completed a suite of standard soil physiochemical measurements (pH, water content, water holding capacity, and bulk density) and are in the process of finishing additional physiochemical measurements (aggregate distribution, total phosphorous, nitrate, and ammonium) expected to complete this summer. We have also measured several carbon-related metrics (microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen via chloroform fumigation extraction, total organic carbon and nitrogen, microbial respiration, and soil organic matter). We sent samples to Brookside Labs to analyze carbon-to-nitrogen ratios, and to RegenAg Labs to complete PLFA analysis and are awaiting results.

We are measuring CUE using the 18O-water stable isotope tracing method. This method requires taking two subsamples from each soil sample. One is incubated with labeled 18O isotope water, the other with non-labeled water to represent natural isotope abundance. Both subsamples are sealed, and after a 24-hour incubation, the total carbon dioxide produced (respiraiton) is measured using a gas chromatograph (SRI instruments, Model 310C). One then extracts DNA from each sample using DNeasy PowerSoil Pro kits (Qiagen), then sends these extracts out for 18O stable isotope analysis. I have completed initial incubations, labeled water additions, and respiration measurements. I am in the process of extracting DNA to send to Cornell for stable isotope analysis.

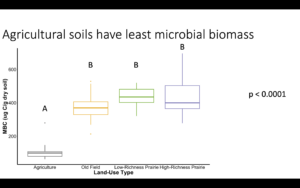

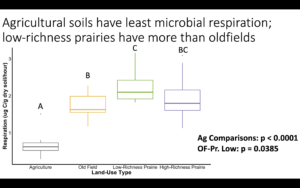

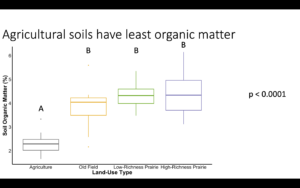

The patterns from our initial results (microbial biomass carbon, microbial respiration, and soil organic matter) indicate that while oldfields, low-richness prairies, and high-richness prairies tend to show higher carbon and higher microbial activity than agricultural fields, they do not differ much from each other. In the attached graphs, different letters indicate means are significantly different from each other at the p < 0.05 threshold.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation Summary:

I attended two outreach events at the Kellogg Biological Station, where I connected with local farmers & landowners on a one-on-one basis for relationship building and informal conversation about interest in questions raised by the funded work. In September 2023, I attended the KBS LTAR Farmer Field Day, and in January 2024, I attended the KBS LTAR Summit.

I am working with Dr. Liz Schultheis to coordinate presenting our results at outreach events in Summer 2024.

Project Outcomes

We are still in the data collection and analysis phase of the project. Our goals for project outcomes include:

Learning Outcomes: After presenting our results to local stakeholders and the larger scientific community, I expect both audiences will have an increased awareness of the benefits of establishing prairie plantings in agricultural systems and increased knowledge of the trade-offs associated with different prairie management techniques. I also anticipate that both audiences will have an increased appreciation for the importance of soil microbial communities to soil health – specifically, to soil carbon dynamics.

Action Outcomes: After attending our summary presentation or reading our educational materials, I anticipate land managers will have increased openness to installing prairies on their farms and increased openness to considering belowground-minded management.