Final report for GNC22-344

Project Information

Background

Sustainable agricultural practices like agroforestry are necessary to ensure global food security, mitigate climate change, conserve biodiversity, and provide ecosystem services. Such practices can also boost economic profitability, protect human health, and enhance well-being. Agroforestry, defined as the integration of trees into crop and livestock systems, is widely promoted as a sustainable land use practice. However, the adoption of these practices remains limited in the US. The need for agroforestry assessments has been identified in national statements like the USDA Agroforestry Strategic Framework. We have also identified this need through key informant interviews with extension agents, USDA personnel, non-profit organizations, and producers. This project assesses the social-ecological suitability and pathways for expanding agroforestry in the Midwest to support US agroforestry policy and programs.

Research Approach and Summary of Results

We focused on assessing the feasibility of expanding agroforestry in Illinois through geospatial analysis, modeling, and semi-structured interviews with producers and program administrators. Given important recent investments in expanding US agroforestry (The Nature Conservancy, 2022), this work aims to identify target areas for agroforestry practices and describe perceived opportunities and barriers to an appropriate agroforestry expansion based on stakeholder inputs.

Agroforestry Suitability Modeling

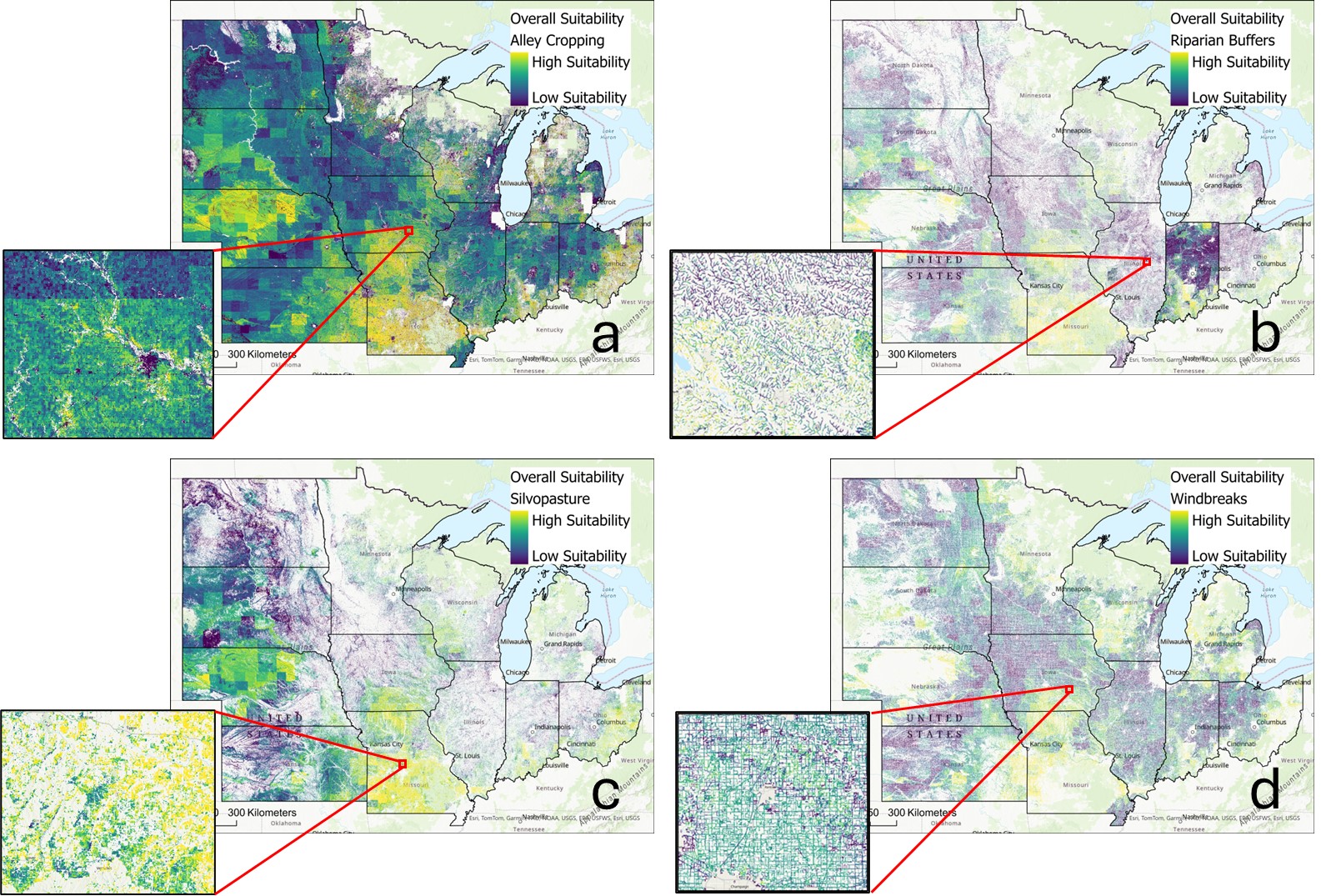

High-resolution maps showing the potential suitability of agroforestry based on social, economic, and biophysical factors (“suitability maps”) can be powerful resources for decision-makers to design and target agricultural conservation programs effectively. The results of this work will help inform agricultural policies promoted by governments and organizations, improve targeting of programs, and inform farmers’ decisions based on environmental and economic suitability models. Using a range of relevant environmental and socioeconomic criteria, we found that agroforestry is predicted to have the highest potential for expansion in southern and western Illinois. Throughout the entire US Midwest, agroforestry had the highest overall social-ecological suitability throughout much of Missouri, south-central Iowa, western Nebraska, eastern Kansas, southeastern Wisconsin, and eastern Ohio through southern Indiana and Illinois.

Our findings suggest that agroforestry has substantial potential to address environmental and social concerns throughout the Midwest by improving environmental conditions and creating new sustainable systems that support communities and livelihoods. Our analysis integrates environmental, social, and economic data at different spatial resolutions to identify agroforestry program priority areas while offering the flexibility to target based on specific selected features. Agroforestry strategically targeted to these areas of the Midwest is estimated to generate almost five times more carbon storage potential than cover cropping on the same areas.

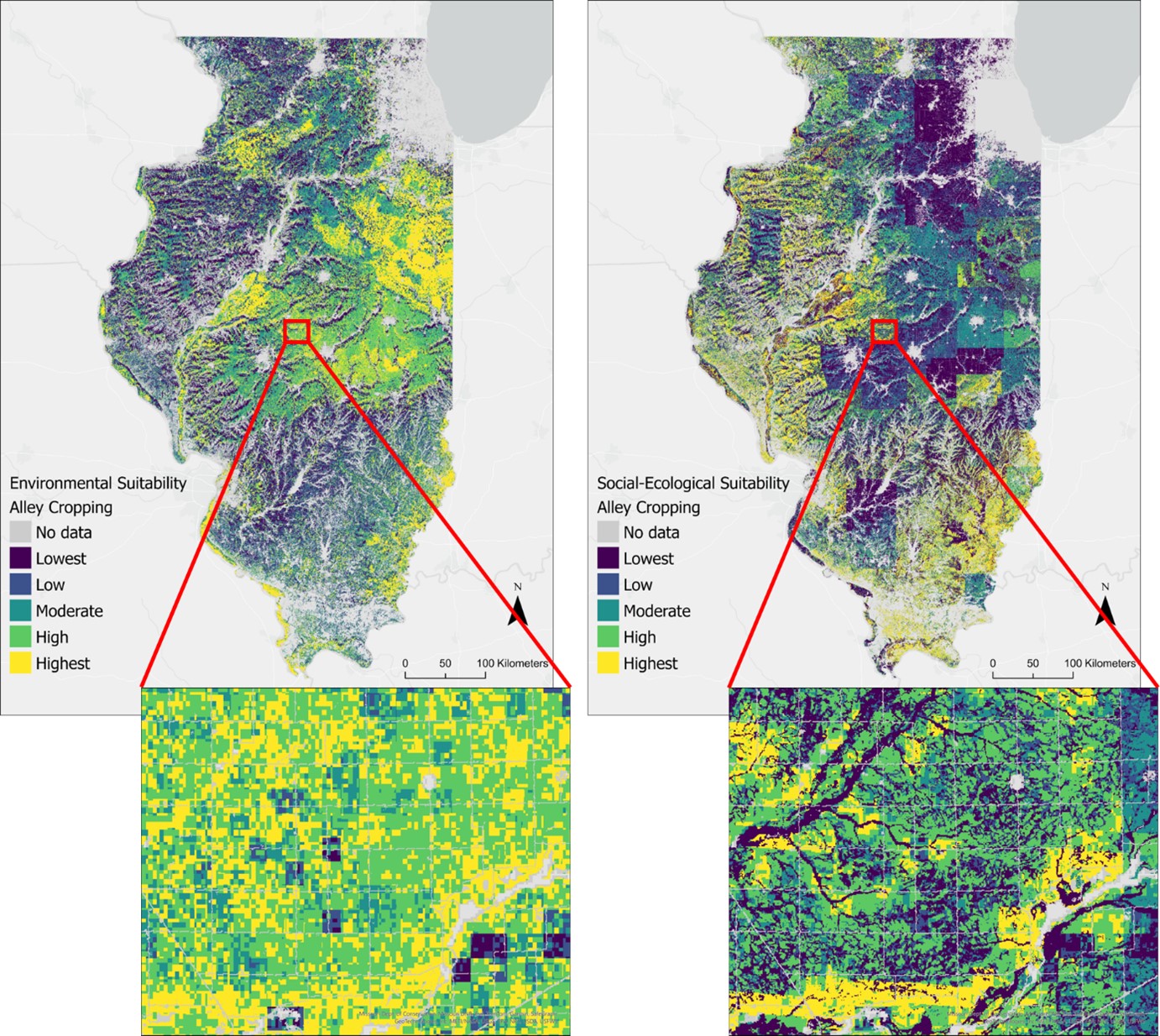

We also emphasize the importance of including socioeconomic variables in suitability mapping. Some areas with high opportunities to use agroforestry to address environmental concerns may have implementation challenges due to social, economic, and tree growth constraints. Specific examples include central Illinois, central and northern Iowa, and northern Indiana. However, considering that agroforestry is a voluntary conservation and production practice, typically carried out by private landowners, the feasibility of using it as a sustainability solution needs to include the environmental priorities along with social and economic feasibility. This more holistic– and realistic– approach may inform more effective agroforestry interventions.

Agroforestry transitions: stakeholder perceptions of agroforestry in the US Midwest

The agroforestry suitability maps were complemented by an analysis of Illinois producers’ and program administrators’ perceptions of agroforestry’s suitability using a scenario of expanding agroforestry to 5-10% of their farmland and to agricultural lands within their county of residence. We assessed the perceived nature values attributed to agroforestry, the role of values in adoption decisions, and the barriers and opportunities in transitioning towards an agroforestry landscape. We found that relational values and non-material values played key roles in agroforesters’ adoption decisions, which has been found in other temperate contexts around the world. In understanding the role of nature values in determining adoption, policies and programs may be designed to align with producer priorities. The assessment of agroforestry’s nature values also suggests that agroforestry could be framed to align with different stakeholder groups and incorporated into policies with aligned missions. For example, the Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy currently only includes minimal reference to agroforestry. Additionally, there was a strong perception that agroforestry has the potential to promote rural development and reduce poverty by establishing new markets and agrotourism, which could also help incorporate agroforestry into rural development policies.

Overall, agroforestry adopters and program administrators had positive perceptions of the agroforestry transition scenario, citing potential benefits to nature, ecosystem services, and quality of life. On the other hand, conventional farmers had mixed views, with overall moderate to strong negative views of the agroforestry scenario, primarily due to concerns over production, economics, and management challenges. A primary difference between agroforestry adopters and non-adopters was their view on the material value of agroforestry: agroforestry practitioners viewed agroforestry as an opportunity to diversify production, generate new revenue streams, and produce nutritious foods and high value/value-added goods whereas non-practitioners (e.g. “conventional” farmers) tended to view agroforestry as taking land out of production for conservation purposes.

Summary of Conclusions

This project contributes to interdisciplinary knowledge on land use science and policy, sustainability science, and agroforestry. First, land systems are interdependent with the meaning and values humans attribute to them. Understanding the diverse values people attribute to landscapes is critical for including multiple values into policymaking to create more just and sustainable solutions. Additionally, in better understanding the challenges and policy barriers agricultural producers face when considering conservation practices like agroforestry, conservation policies could integrate this knowledge generated by producers and practitioners. Conservation policies could be adapted to allow greater flexibility that accounts for the multiple goals and values of potential implementers to meet both the environmental goals of conservation policy as well as the socioeconomic goals often prioritized by the land operators. Additionally, by including multiple social-ecological variables into the agroforestry suitability model (soil erosion, water quality, soil organic carbon sequestration potential, tree species suitability, net farm income, demographic, and conservation norms), the model generated estimates of areas where agroforestry could meet multiple objectives, rather than focusing on singular goals. This type of assessment provides a more holistic view of agroforestry’s potential to provide solutions for multiple interests and garner greater social and political support. The geospatial analysis was complemented by qualitative work to form a more comprehensive assessment of agroforestry’s suitability in Illinois and inform policy and incentive structures to advance sustainability science.

The overarching goal of this research project is to inform Midwest agroforestry policy through assessing feasibility of transitioning land to agroforestry at a large scale using a geospatial suitability assessment and interviews with stakeholders in Illinois. The methods and tools developed through this project will lay the foundation to evaluate the political and economic feasibility of agroforestry in the US.

To achieve this goal, the project includes two interlinked objectives: (1) map the suitability of agroforestry practices and predict priority areas for agroforestry development across the US Midwest, and (2) conduct semi-structured interviews with producers and program administrators throughout Illinois to understand the perceived feasibility of expanding agroforestry in Illinois and assess the roles of nature values in determining agroforestry adoption decisions. The results of these objectives will contribute towards the US agroforestry agenda and provide insights to shape future agroforestry policy.

Agroforestry Suitability Modeling

To meet the first objective, we conducted an agroforestry multi-criteria decision analysis to address the following research questions.

- Where in the US Midwest could agroforestry be targeted to offer the greatest environmental benefits while considering socioeconomic feasibility?

- What are the potential benefits and tradeoffs of transitioning current agricultural systems to agroforestry, and what are the policy implications for supporting efficient expansion of agroforestry in the US Midwest?

To meet this first objective, we have developed agroforestry suitability maps using geospatial analysis and modeling to identify potential priority areas for targeting agroforestry in Illinois as well as the twelve-state north-central region (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin). This suitability map shows regions where agroforestry is expected to reduce the risk of environmental degradation, support productive tree growth, and be socioeconomically viable. This framework for agroforestry suitability modeling was developed based on agroforestry literature and key informant interviews to identify model parameters and user needs. We created separate maps for alley cropping, riparian buffer, silvopasture, and windbreak suitability. Results reveal considerable opportunities for expanding agroforestry practice within specific regions, where policies could be targeted. The suitability map can be used to inform agricultural conservation policy and decision-making related to agroforestry in specific locations. This work also provides a theoretical foundation for interdisciplinary suitability modeling that can be adapted for use in other global regions.

Agroforestry transitions: stakeholder perceptions of agroforestry in the US Midwest

To meet the second objective, we focused on agroforestry practices within the state of Illinois as a case study to examine stakeholder views of an agroforestry landscape transition (increasing agroforestry up to 5-10% of agricultural land).

The goal of this research project is to advance agroforestry knowledge and policy through understanding stakeholder perceptions of agroforestry in the Illinois context. We conducted semi-structured interviews with Illinois crop producers, livestock producers, and program administrators to answer the following research questions:

- What are the intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values attributed to agroforestry practices? To what extent do producers’ values (intrinsic, instrumental, relational) inform their agroforestry adoption decision?

- To what extent do agricultural stakeholders support a local expansion of agroforestry?

- What are the positive, negative, and neutral perceptions of an agroforestry landscape scenario (transitioning 5-10% of agricultural land to agroforestry within their county or administrative region)?

- What are the perceived opportunities and barriers to expanding agroforestry in Illinois, and what are the implications for agroforestry policy?

We analyzed the roles of nature values in determining agroforestry adoption decisions to inform more sustainable and reflexive agroforestry planning and policy. We conducted semi-structured interviews with producers (18 agroforesters and 8 conventional farmers) and program administrators (13) throughout the northern, central, and southern regions of Illinois. We examined the perceived positive, negative, and neutral values of agroforestry on nature (intrinsic), ecosystem services (instrumental), and quality of life (relational). We then assessed how the values of participants influenced their adoption decisions and explored the perceived opportunities and barriers for expanding agroforestry in the region, including those related to financial risk and funding, management, equipment and plant material, market access, science knowledge and education, and climate change.

Summary of Outputs

The outcomes of the first objective included creating and disseminating the suitability map as an interactive tool for policymakers, agencies, and producers. Our paper on the agroforestry decision support tool is currently under review at Environmental Research Letters. We developed an agroforestry decision-support tool as a Google Earth Engine app, which will be publicly available and distributed through relevant organizations, including University of Illinois Extension and Iowa Learning Farms, among others. The Agroforestry Decision Support Tool is available publicly here: https://agroforestrymap.projects.earthengine.app/view/agroforestry-suitability-tool. The tool is currently in beta testing with potential end-users. Preliminary results were shared at the 2023 Forests and Livelihoods: Assessment, Research, and Engagement Meeting in Nairobi, Kenya on October 14, 2023 (https://www.forestlivelihoods.org/annual-meeting-2023/), the Iowa Learning Farms Webinar Series on April 24, 2024 (https://www.iowalearningfarms.org/webinars), and the 2024 Agriculture, Food & Human Values Society (AFHVS) and the Association for the Study of Food and Society (ASFS) Conference held in Syracuse, New York. Continued conversations with policymakers and stakeholders will help us track all the above outcomes. The expected outcomes of the first objective include reaching researchers and policymakers to illustrate the potential contributions of agroforestry and enable future research quantifying the impacts of agroforestry. We will track this outcome through the citations and downloads of our publications and repository/tool access counts.

The expected outcomes of this second objective include delivering summaries and publications to the interview participants. We currently have two manuscripts in preparation based on the results of the semi-structured interviews: (1) paper focused on the role of nature values in agroforestry adoption decision-making (target journal: Ecosystem Services), and (2) paper focused on agroforestry transitions and the opportunities and barriers to agroforestry adoption in Illinois (target journal: Land Use Policy). We collected information from agroforester interviewees related to their direct experiences with conservation policy, agroforestry management, and specific challenges and solutions they found in managing agroforestry systems. We plan on disseminating infographics and informal publications to inform agroforestry policy and program needs and share participants insights to agroforestry success.

Cooperators

- (Researcher)

- (Researcher)

Research

Objective 1: Agroforestry suitability mapping

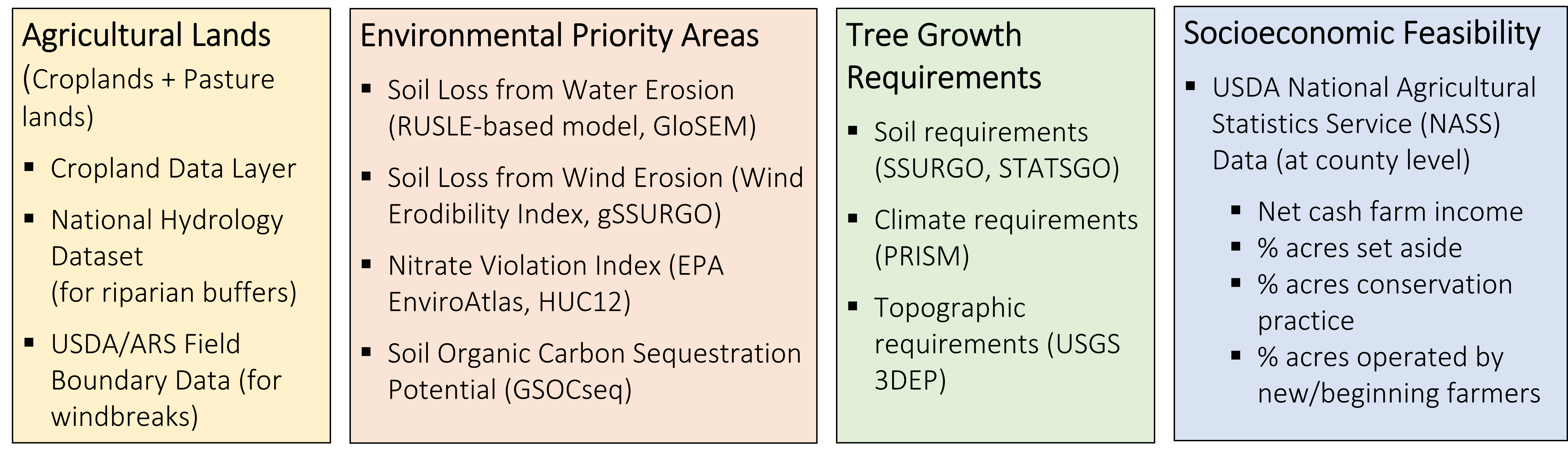

We used GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis to identify target regions for agroforestry expansion based on tree productive growth requirements, environmental priority areas, and socioeconomic criteria (Figure 1). We generated suitability maps for the four of the five major agroforestry practice types in the US that focus on tree planting: (1) alley cropping, (2) silvopasture, (3) riparian buffers, and (4) windbreaks. We did not include forest farming in our assessment since the practice primarily transitions current forests to include productive elements, rather than converting current crop or grazing lands.

Each of the suitability criteria were normalized for consistency between variables using a linear function. Counties with less than 5% of the total land in agriculture were removed from our analysis since the social and economic indicators were not comparable. The overall suitability was estimated using the weighted linear sum method for multi-criteria decision-making. Where appropriate, weights were selected based on literature reviews and expert input, and where justifiable weights were unavailable the variables were equally weighted. The NRCS reporting of the relative physical effects was used for weighting the environmental priority variables for each practice. Suitability was on a scale from 0-1, where 1 indicated the areas where agroforestry offers the greatest potential benefits in terms of environmental risks, tree growth suitability, and social feasibility.

Objective 2: Semi-structured interviews with producers and program administrators in Illinois

We used a qualitative research approach to examine the opportunities and barriers to agroforestry adoption as well as the relative importance of environmental, social, and economic criteria within interviewees’ decision-making processes. The fieldwork consisted of individual in-person or virtual interviews with a diverse set of farmers and ranchers in Illinois. We also interviewed program administrators within governmental and non-governmental organizations (e.g., Farm Service Agency, USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service, USDA Forest Service, university extension) to understand their perspectives on the policy landscape of agroforestry in the US Midwest. Farmers and ranchers were recruited from southern, central, and northern Illinois, and program administrators were recruited primarily from Illinois but also from among those based elsewhere in the Midwest but with knowledge relevant to Illinois.

We conducted semi-structured interviews as a means to understand individual perceptions of the roles of trees in agricultural landscapes. Semi-structured interviews allow interviewees the freedom to express their views in their own terms, provide space for more in-depth exploration of their views and reasoning, and offer more privacy in their responses. We explored different aspects of the topic in depth with each interviewee, and these interviews allowed us to ask follow-up questions and probe interviewees for specific examples and ideas. The consistent questions and structure of the interviews helped provide reliable, comparable qualitative data. Additionally, semi-structured interviews allowed us to gather subjective data to analyze participant’s personal values that could not be gathered using other methods.

Our interview guide followed five broad categories:

- Farmer and program administrator characteristics and background.

- Interviewees’ motivations and values and the values they attribute to agroforestry.

- Interviewees’ perceptions of trees in the agricultural landscape and of an agroforestry landscape scenario (transitioning 5-10% of agricultural land to agroforestry in county), including perceived benefits and downsides.

- Interviewees’ perceived agroforestry adoption decision criteria and barriers to agroforestry adoption.

- Interviewees’ experiences with programs, policies, and other types of assistance, including their perceived gaps and opportunities in policy.

This study was approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Review Board (IRB) for research on human subjects. All participants received a consent form and gave oral consent to participate in our study at the start of the interview.

We used purposive sampling to select initial participants for the semi-structured interviews, relying on internet searches and contacts through key members of our network to collect the initial list. We did not set our sample size prior to conducting our study. Instead, we worked inductively towards theoretical saturation. The initial set of participants represented individuals from the following overlapping groups: agroforestry farm operators (crops and/or livestock), non-agroforestry farm operators (crops and/or livestock), local organizations, state agency personnel, university extension, and regional organizations. The initial set of interviewees suggested new contacts, who they reached out to on our behalf. Purposive sampling using chain referrals continued in this way, and we used a strategic approach to select additional participants until each of the groups were sampled to theoretical saturation. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and imported into NVivo 14 for analysis. We used Zoom transcriptions and TranscribeMe for initial machine learning transcriptions, which we then manually cleaned. We used NVivo to identify and analyze themes in the data through coding into descriptive categories.

US Midwest Agroforestry Suitability Map

Agroforestry had the highest overall social-ecological suitability throughout much of Missouri, south-central Iowa, western Nebraska, eastern Kansas, southeastern Wisconsin, and eastern Ohio through southern Indiana and Illinois. Western Nebraska had fewer identified opportunities for riparian buffers due to fewer surface water bodies. Spatial patterns shifted somewhat when environmental priority areas were weighted similarly to the combined social and economic criteria (i.e., by multiplying the environmental priorities layer by two before adding with the social and economic layers) instead of weighing all three layers equally).

Comparing environmental-only suitability maps with overall social-ecological suitability maps, the target areas for agroforestry also shift considerably. Some areas with high opportunities to use agroforestry to address environmental concerns may have implementation challenges due to social, economic, and tree growth constraints. Specific examples include central Illinois, central and northern Iowa, and northern Indiana.

We extracted the areas identified as the top 5% of lands most suitable for agroforestry for each of the four agroforestry practices to estimate the potential carbon storage contributions of converting those lands to agroforestry practices using the COMET-Planner tool. Results show that an agroforestry transition to these lands best suited for agroforestry based on our criteria (totaling 23.6 million acres) has the potential to store 43 [29-58] megatonnes of CO2 per year. We also find that such a transition would store considerably more carbon than a transition to cover cropping. If the same lands were transitioned to cover crops with a 25-50% reduction in fertilizer N, approximately 8.4 [-2.3-23.6] megatonnes CO2 eq./year would be stored, or some five times less than agroforestry.

While we procured some expert input on the selection and weighting of criteria, the priorities may shift between users and over time. Accordingly, we translated our model into a publicly available decision-support tool as a Google Earth Engine app, currently in beta testing, available at the following link: https://agroforestrymap.projects.earthengine.app/view/agroforestry-suitability-tool. The tool allows users to define which criteria to use, weigh them according to their own priorities, and select their scale of analysis (Midwest, state, county, or watershed). It also allows users to explore in the results in high resolution for planning. Users can also view the layers that make up the overall suitability map, visualizing: environmental priority areas, tree growth suitability, economic viability, and social feasibility.

Agroforestry in Illinois

Suitability map

Agroforestry was determined to have the highest suitability throughout southern and western Illinois when using the full social and environmental criteria. When considering only the potential of agroforestry to address environmental goals, central and northern Illinois had higher potential for expanding agroforestry, though we expect that the ability to competitively grow diverse agroforestry species and gain social acceptability would be more challenging in these regions. The shifted priorities from including the socioeconomic dimensions of agroforestry’s suitability reflected the expert expectations conveyed during key informant interviews with Midwestern agroforestry experts. We explore these themes further through formal, semi-structured interviews with producers and program administrators throughout Illinois. Additionally, we found that there are large carbon storage potential benefits through expanding agroforestry on highly suitable Illinois lands. We also identified thousands of acres with potential suitability for agroforestry in terms of environmental objectives, tree growth requirements, and social feasibility that were estimated to be marginal (low crop value) lands.

We used a qualitative research approach to examine the opportunities and barriers to agroforestry adoption as well as the relative importance of environmental, social, and economic criteria within interviewees’ decision-making processes. The fieldwork consisted of individual in-person or virtual interviews with a diverse set of farmers and ranchers in Illinois (Table 1). We also interviewed program administrators within governmental and non-governmental organizations (e.g., Farm Service Agency, USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service, USDA Forest Service, and university extension) to understand their perspectives on the policy landscape of agroforestry in the US Midwest. Farmers and ranchers were recruited from southern, central, and northern Illinois, and program administrators were recruited primarily from Illinois but also from among those based elsewhere in the Midwest but with knowledge relevant to Illinois.

Table 1: Summary table of the number and types of interviewees

|

Category |

Interviewee group |

Number of interviews (participants, where different) |

|

|

Farm type (Producers only) |

Agroforester |

Annual crops + perennial crops |

14 (17) |

|

Livestock + perennial crops |

1 (2) |

||

|

Annual + perennial crops + livestock |

3 (4) |

||

|

Total agroforesters |

18 (23) |

||

|

Non-agroforester |

Annual crops |

7 |

|

|

Livestock |

0 |

||

|

Total non-agroforesters |

7* |

||

|

Adoption category |

Full-farm agroforestry adopter |

13 (18) |

|

|

Partial-farm agroforestry adopter (trial or edge) |

5 |

||

|

Potential agroforestry adopter |

4 |

||

|

Would not currently adopt agroforestry |

3 |

||

|

Region of operation (Producers only) |

Southern Illinois |

12 |

|

|

Central Illinois |

6 |

||

|

Northern Illinois |

6 |

||

|

Acres operated (Producers only) |

Under 101 acres |

13 |

|

|

101-1000 acres |

8 |

||

|

Over 1000 acres |

3 |

||

|

Farm ownership (Producers only) |

Owns and operates only |

11 |

|

|

Rents and operates only |

4 |

||

|

Both owns and rents operated land |

6 |

||

|

Owns and operates, and rents out to others |

3 |

||

|

Off-farm job (Producers only) |

No off-farm job |

3 |

|

|

Part-time off-farm job |

15 |

||

|

Retired |

5 |

||

|

Program region (Program administrators only) |

Local (county) |

2 |

|

|

State or multi-county region |

8 |

||

|

Multi-state region or national |

3 |

||

|

Total program administrators |

13** |

||

|

Gender identity (All participants) |

Female |

13 |

|

|

Male |

27 |

||

|

Other |

0 |

||

|

Age (All participants) |

Under 25 |

0 |

|

|

26-35 |

3 |

||

|

36-45 |

11 |

||

|

46-55 |

8 |

||

|

56-65 |

8 |

||

|

Over 65 |

5 |

||

Table 1 Notes:

* One conventional farmer was maintaining their windbreaks and riparian buffers, but they did not intentionally plant or harvest them. We interviewed an eighth conventional farmer; their data has not yet been analyzed.

** Three program administrators were also producers. We analyzed their responses primarily as producers, but their broader responses concerning policy and working with other producers were also analyzed.

Through the semi-structured interviews, we found that overall, there was some misalignment between the perceived value of agroforestry and the individual values held by farmers in Illinois, particularly with the values farmers prioritized in their adoption decision-making. While the early adopters of agroforestry, along with many of the program administrators, viewed agroforestry as a potential opportunity for production and profitability, non-adopters tended to view agroforestry as strictly taking land out of production for conservation. The early adopters were willing to seek out relevant resources and information, take financial risk with the expectation of long-term gain, and be creative in finding near-term solutions. We found that the primary motivations that farmers had for adopting agroforestry were relational values: helping their community, working in harmony with nature, and enjoyment in farming. There were also strong non-material values in terms of supporting a stewardship identity and creating farming systems that provide sustainable options for the current and future generations. While most adopters shared appreciation for the numerous regulating and intrinsic values of agroforestry that they perceived, these were often not the primary motivators of their adoption decisions, except for those who had adopted partial-farm agroforestry to reduce problems with soil erosion.

Table 2: Number of interviewees mentioning their positive, negative, and neutral perceptions of agroforestry’s value to deliver intrinsic, instrumental, and relational outcomes. Green cells indicate a relatively higher number of mentions and yellow cells indicate a relatively lower number of mentions.

|

Perceived values of agroforestry using IPBES framework |

||||

|

Value type |

Identified ecosystem service |

Positive perceptions (number of interviewees) |

Negative perceptions (number of interviewees) |

Neutral perceptions |

|

Intrinsic |

Nature's value (e.g., intrinsic value of biodiversity) |

n = 21 (13 AF, 2 NAF, 6 PA) |

- |

n = 1 (1 NAF) |

|

Instrumental – Material1 |

Energy provision |

n =1 (1 AF) |

- |

- |

|

Food and feed provision |

n = 22 (18 AF, 4 PA) |

n = 4 (4 NAF, 2 PA) |

n = 1 (1 PA) |

|

|

Genetic resources |

n = 4 (4 AF) |

- |

- |

|

|

Medicinal resources |

n = 2 (2 AF) |

- |

- |

|

|

Other material resources (timber, florals) |

n = 11 (7 AF, 1 NAF, 3 PA) |

- |

- |

|

|

Instrumental - Regulating |

Air quality |

n = 1 (1 PA) |

- |

- |

|

Climate regulation |

n = 12 (7 AF, 5 PA) |

- |

- |

|

|

Habitat creation and maintenance |

n = 14 (6 AF, 6 PA, 2 NAF) |

- |

- |

|

|

Pollination and dispersal of seeds |

n = 2 (2 AF) |

- |

- |

|

|

Instrumental - |

Regulating hazards and extreme events |

n = 11 (5 AF, 5 PA, 1 NAF) |

- |

- |

|

Regulating organisms and contaminants harmful to humans |

n = 14 (7 AF, 6 PA, 1 NAF) |

- |

- |

|

|

Soil quality and erosion |

n = 21 (10 AF, 9 PA, 2 NAF) |

- |

- |

|

|

Water quality |

n = 9 (1 AF, 7 PA, 1 NAF) |

- |

- |

|

|

Water quantity, flows, and timing |

n = 3 (2 AF, 1 PA) |

- |

- |

|

|

Instrumental - Non-material |

Learning and inspiration |

n = 5 (5 AF) |

- |

- |

|

Maintenance of options |

n = 8 (6 AF, 2 PA) |

- |

- |

|

|

Physical and psychological experiences |

n = 15 (11 AF, 4 PA) |

- |

- |

|

|

Relational |

Healthy way of life and good quality of life |

n = 10 (8 AF, 2 PA) |

- |

n = 1 (1 NAF) |

|

Social and community impact |

n = 13 (11 AF, 2 PA) |

n = 1 (1 NAF) |

n = 1 (1 NAF) |

|

|

Living in harmony with nature |

n = 4 (4 AF) |

- |

- |

1Includes the economic value of the material goods

We found that overall, there was some misalignment between the perceived value of agroforestry and the individual values held by farmers in Illinois, particularly with the values farmers prioritized in their adoption decision-making. While the early adopters of agroforestry, along with many of the program administrators, viewed agroforestry as a potential opportunity for production and profitability, non-adopters tended to view agroforestry as strictly taking land out of production for conservation. The early adopters were willing to seek out relevant resources and information, take financial risks with the expectation of long-term gain, and be creative in finding near-term solutions. Key opportunities for expanding agroforestry included: (1) developing demonstration farm networks to both visualize agroforestry within the landscape and conduct research on economics and management, (2) providing sufficient conservation practice incentives with pricing to match rental rates into the long-term (e.g., beyond the typical 10-year CRP contract), and (3) improving education and messaging by linking the potential benefits of agroforestry to farmers’ goals.

We identified numerous barriers to agroforestry adoption as well as opportunities for overcoming some of those barriers. Most of the barriers were directly related to socioeconomics and crop production: tenure security, temporal gap between investment and revenue, lack of funding, negative tree-crop interactions, and equipment challenges. Two of the primary proposed solutions for addressing these barriers were establishing a demonstration farm network, with economic assessments, as well as providing markets and market resources for selling agroforestry products. These demonstration farms and research could be essential to overcome the current social norms and the view of agroforestry as an unproductive conservation practice that is not worth establishing or managing. Additionally, greater technical support and the expansion of farmer-to-farmer networks to share knowledge and resources could help overcome these barriers.

Agroforestry adopters and conservation program administrators typically had very positive responses to an agroforestry transition using a scenario of 5-10% of land being converted to agroforestry. They viewed such a transition as helping to improve regulating services and quality of life. However, all types of interviewees had concerns that a transition to expanding agroforestry would be met with substantial social and economic barriers. Most of the stakeholders we interviewed expected that there would be substantial social resistance to agroforestry after decades of social norms pushing farmers to remove trees to keep a “tidy” farm with maximum productivity. However, almost everyone we spoke with recognized potential gains to ecosystem services and nature through agroforestry. Overall, there was a perceived potential for expanding agroforestry in Illinois through designing stable, flexible, and appropriate incentive programs coupled with extensive outreach, education, and training to demonstrate the viability and opportunity of agroforestry.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

We presented this work in the Iowa Learning Farms Webinar Series (https://www.iowalearningfarms.org/resources/sarah-castle). There were 93 participants in the webinar, consisting of a mixture of farmers, ranchers, and agricultural professionals (through the distribution is not known). The webinar has been viewed at least an additional 30 times. There was substantial interest in the decision-support tool as well as the results of the semi-structured interviews, and we will disseminate the agroforestry decision-support tool through this group.

We have also been discussing the research design through key informant interviews with members of the USDA National Agroforestry Center, the Savanna Institute, and University of Illinois Extension. We plan to share project summaries and reports with these agroforestry stakeholders to use and disseminate.

We also presented this work to the Forests and Livelihoods: Assessment, Research, and Engagement Network at the 2023 conference in Nairobi. We received positive interest in translating the methodologies to international contexts. We also presented this work at the 2024 Agriculture, Food & Human Values Society (AFHVS) and the Association for the Study of Food and Society (ASFS) Conference in Syracuse, New York. We received valuable feedback and interest in collaborations to expand this work.

We plan on publishing this work as at least four academic journal articles: (1) a paper on the agroforestry suitability map for the US Midwest (currently under review), (2) a paper on the roles of nature values in determining agroforestry adoption decisions and the perceived suitability of an agroforestry transition, (3) a paper on the perceived opportunities and barriers to agroforestry adoption and the policy and program needs for agroforestry in the US Midwest. Additionally, a master's student is working on assessing the role of place attachment in agroforestry adoption, which will be a separate journal article (4). We also published the agroforestry decision-support tool as a Google Earth Engine app: https://agroforestrymap.projects.earthengine.app/view/agroforestry-suitability-tool, for which we plan to publish a separate journal article or dataset description.

Project Outcomes

Given important recent investments in expanding US agroforestry, this work aims to provide evidence and an approach to identify target areas for agroforestry practices and describe perceived opportunities and barriers to an appropriate agroforestry expansion based on stakeholder inputs. As such, this project can inform agroforestry practice and policy in Illinois, with implications for the US Midwest and beyond.

Our suitability map shows regions where agroforestry is expected to reduce the risk of environmental degradation, support productive tree growth, and be socioeconomically viable. Results revealed considerable opportunities for expanding agroforestry practice within specific regions, where policies could be targeted. The suitability map can be used to inform agricultural conservation policy and decision-making related to agroforestry in specific locations. This work also provides a theoretical foundation for interdisciplinary suitability modeling that can be adapted for use in other global regions. We provide access to this tool through a publicly available app, where decision-makers can set their own parameters and priorities for specific Midwest regions to guide their agroforestry-related programming: https://agroforestrymap.projects.earthengine.app/view/agroforestry-suitability-tool.

A transition to expanding agroforestry in Illinois can be better informed by acknowledgment of nature’s many values perceived by stakeholders and co-designing agroforestry-related policies according to the plurality of values identified within our study. We found key motivations among agroforestry adopters related to their non-material, relational, and regulating values. Among agroforesters and conventional producers alike, material values played a key role in the viability of agroforestry practice to ensure long-term viability of the operations. There was substantial heterogeneity in our results, with multiple values motivating the adoption decision around agroforestry, highlighting the nuance and complexity in understanding how values drive adoption decisions. We attempted to provide some simplification by drawing out themes from the semi-structured interviews, but there were individual perspectives that we could not fully capture through thematic analysis. By highlighting the main themes and broad associations between values and adoption decisions, this work may help inform policy, program, messaging, and targeting for larger landscapes.

We also explicitly looked at the feasibility of expanding agroforestry in Illinois through a joint assessment of suitability and the perceived opportunities and barriers to adoption as well as policy needs. This work provides examples of farmer successes and challenges when implementing agroforestry in Illinois, creating a shared resource for guiding extension and training programs.

Understanding the diverse values people attribute to landscapes is critical for including multiple values into policymaking to create more just and sustainable solutions. Additionally, in better understanding the challenges and policy barriers agricultural producers face when considering conservation practices like agroforestry, conservation policies could integrate this knowledge generated by producers and practitioners. Conservation policies can be adapted to allow greater flexibility that accounts for the multiple goals and values of potential implementers to meet both the environmental goals of conservation policy as well as the socioeconomic goals often prioritized by the land operators. Additionally, by including multiple social-ecological variables into the agroforestry suitability model (soil erosion, water quality, soil organic carbon sequestration potential, tree species suitability, net farm income, demographic, and conservation norms), the model generated estimates of areas where agroforestry could meet multiple objectives, rather than focusing on singular goals. This type of assessment provides a more holistic view of agroforestry’s potential to provide solutions for multiple interests and garner greater social and political support. The geospatial analysis was complemented by qualitative work to form a more comprehensive assessment of agroforestry’s suitability in Illinois and inform policy and incentive structures to advance sustainability science.

A transition to expanding agroforestry in Illinois can be better informed by acknowledgment of nature’s many values perceived by stakeholders and co-designing agroforestry-related policies according to the plurality of values identified within our study. We found key motivations among agroforestry adopters related to their non-material, relational, and regulating values. Among agroforesters and conventional producers alike, material values played a key role in the viability of agroforestry practice to ensure long-term viability of the operations. There was substantial heterogeneity in our results, with multiple values motivating the adoption decision around agroforestry, highlighting the nuance and complexity in understanding how values drive adoption decisions. We attempted to provide some simplification by drawing out themes from the semi-structured interviews, but there were individual perspectives that we could not fully capture through thematic analysis. By highlighting the main themes and broad associations between values and adoption decisions, this work may help inform policy, program, messaging, and targeting for larger landscapes.

Our project draws several conclusions and recommendations for future directions related to temperate agroforestry. Calls have long been made for demonstration farms capable of showing the viability of agroforestry within the landscape and to conduct local research on tree species and management. This desire was reflected among Illinois stakeholders, who shared that a demonstration farm network could shift social norms around trees in the agricultural landscape while providing research on economics and management and access to locally adapted tree germplasm.

Beyond demonstration farms, farmer-to-farmer peer networks could play an important role in advancing agroforestry in Illinois. The agroforestry adopters I spoke with described long and complex processes of gathering the information they needed to start working with agroforestry. Compiling these resources and providing access to new agroforesters to experienced agroforesters could make this transition simpler for other farmers who are interested in agroforestry but have more limited resources. Our work interviewing producers throughout Illinois has allowed us to compile considerable knowledge, which we plan to disseminate within the coming months.

Finally, this research holds important implications for designing incentive programs for agroforestry. Unlike other conservation practices, growing trees is inherently a long-term endeavor. Once trees are established, they are costly to remove, and the uncertainty in programs like CRP over the life span of an agroforestry system was a deterrent to potential adopters. Additionally, there were concerns about overly complex restrictions within current programs to allow for the burgeoning interest in productive agroforestry systems. Productive agroforestry systems in themselves may be more viable for producers to adopt and help overcome the uncertainty in incentive programs since once a CRP contract, for example, expires, the agroforestry system could be mature and yielding products. Restrictions on plant material sourcing, plant species, and system arrangements were barriers to agroforestry adopters who were creating diverse, multifunctional systems but could not have access to programs providing conservation incentives or crop insurance. These findings suggest possible avenues for adapting current policies to better support the uptake of agroforestry for greater sustainability – environmental, social, and economic – in Illinois and beyond.