Final report for GNC22-346

Project Information

The Central Great Plains (CGP) is characterized by a semi-arid climate with relatively low annual precipitation (~300 to ~1200 mm) (Lenssen et al. 2007; NOAA 2024). To conserve soil moisture and to prevent soil erosion by wind, no-tillage (NT-) and fallow-based cropping systems are widely adopted in the region. Successful adoption of these soil conservation practices was achieved utilizing chemical-based weed control (Hansen et al. 2012; Kumar et al. 2020). However, the adoption of NT-based production systems has resulted in weed species representing smaller-seeded weeds like kochia [Bassia scoparia (L.) A.J. Scott], Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri S. Watson), horseweed [Erigeron canadensis (L.) Cronquist], common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album L.), Russian thistle (Salsola tragus L.), downy brome (Bromus tectorum L.), wild oat (Avena fatua L.), foxtail species (Setaria spp.), and tumble windmill grass (Chloris verticillata Nutt.) (Jha et al. 2016; Nichols et al. 2015).

Winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)-grain sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench]-fallow (W-S-F) is a dominant crop rotation in the CGP region (Holman et al. 2022). This 3-year crop rotation includes a fallow period of approximately 10 months between winter wheat harvest and sorghum planting as well as 10 months of fallow period between sorghum harvest and the next winter wheat planting (Kumar et al. 2020). Continuous reliance on herbicides with the same site(s) of action for weed control has resulted in the evolution of herbicide-resistant weeds, including B. scoparia, A. palmeri, and E. canadensis (Heap 2024). For instance, glyphosate resistance is widespread among B. scoparia and A. palmeri populations in Kansas and other neighboring states in the CGP region (Heap 2024; Kumar et al. 2019a, 2019b, 2020; Westra et al. 2019). Evolution of glyphosate-resistant (GR) weed populations and limited availability of alternative effective herbicide options pose a serious production challenge for grain sorghum producers in the region. Previous researchers have reported that season-long weed interference can result in an average grain yield loss of 47% in sorghum, which is an estimated loss of around US $953 million annually (Dille et al. 2020). Therefore, alternative integrated weed management strategies are needed to achieve effective control of herbicide-resistant weed populations in grain sorghum.

Integration of cover crop (CC) in crop rotations has been proven as one of the effective tools to suppress herbicide-resistant weeds in the CGP region (Kumar et al. 2020; Mesbah et al. 2019; Obour et al. 2022a; Petrosino et al. 2015). Growing CC in the semi-arid CGP also provides several other benefits, including reduced soil erosion, enhanced nutrient cycling, increased microbial activity, improved soil health, and increased plant diversity and pollinator resources (Blanco-Canqui et al. 2011, 2013; Simon et al. 2022). Additionally, CC residue left on the soil surface after termination reduces soil temperature and soil moisture evaporation, thereby contributing to increased soil water storage (Holman et al. 2020, 2021). However, replacing the fallow period with CC in the semi-arid cropping systems sometimes reduces the yield of successive crops because of the reduced plant available water (Holman et al. 2018; Nielsen et al. 2016). However, the United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA NRCS) provides some financial support to growers under the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) to pay some of the cost of growing CC and improve net returns (Anonymous 2024). Previous studies have evaluated the effect of spring-planted CC on weed suppression and winter wheat yields when CCs replaced the fallow phase of W-S-F rotation in this region (Holman et al. 2022; Mesbah et al. 2019; Obour et al. 2022a). For instance, Obour et al. (2022a) reported that spring-planted CC (oats/triticale/spring peas) in W-S-F rotation can reduce weed biomass by 86 to 99% compared to weedy fallow. Holman et al. (2022) reported that spring-planted CC had no significant effect on wheat and grain sorghum yields when conditions were either extremely dry with poor yields or very wet with above-average yields, however, replacing fallow with CC increased the cost of production by 16 to 97% compared to fallow.

Farmers are currently relying on residual herbicides to manage GR weeds in the dryland W-S-F rotation (Kumar et al. 2020). Several researchers have previously documented the importance of residual herbicides in combination with CC to achieve season-long weed control (Perkins et al. 2021; Whalen et al. 2020). For instance, Whalen et al. (2020) reported that CC terminated with glyphosate plus 2,4-D in combination with residual herbicides (sulfentrazone plus chlorimuron) resulted in greater waterhemp [Amaranthus tuberculatus (Moq.) J. D. Sauer.] control (73 to 84%) compared to no residual herbicide (44 to 65%). Most CC weed suppression research studies were conducted in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), corn (Zea mays L.), or soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] in greater precipitation environments (Weisberger et al. 2023; Whalen et al. 2020). However, limited information exists regarding the integration of fall-planted CC in combination with soil residual herbicides at the termination of CC on weed suppression in subsequent grain sorghum in the semi-arid CGP region.

For fall-planted CC, a mixture (triticale/winter peas/radish/rapeseed) was planted after wheat harvest and terminated at triticale heading stage before sorghum planting. Treatments included nontreated control, chemical fallow, CC terminated with glyphosate (GLY), and CC terminated with GLY+ acetochlor/atrazine (ACR/ATZ). Across three years, CC terminated with GLY+ACR/ATZ reduced total weed density by 34-81% and total weed biomass by 45-73% compared to chemical fallow during the sorghum growing season. Average grain sorghum yield was 786 to 1432 kg ha-1 and did not differ between chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY+ACR/ATZ. However, net returns were lower with both CC treatments (USD -$275 to $66) in all three years compared to chemical fallow (USD -$111 to $120). These results suggest that fallow replacement with fall-planted CC in the W-S-F rotation can help suppress GR B. scoparia and A. palmeri in the subsequent grain sorghum. However, the cost of integrating CC exceeded the benefits of improved weed control and lower net returns were recorded in all three years compared to chemical fallow.

For spring planted CC, a mixture of oats (Avena sativa L.)–barley (Hordeum vulgare L.)–spring peas (Pisum sativum L.) was spring-planted in no-till sorghum stubbles and terminated at oats heading stage. Four treatments, including (1) weedy fallow (no CC and no herbicide), (2) chemical fallow (no CC but glyphosate + flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone + dicamba), (3) CC terminated with glyphosate, and (4) CC terminated with glyphosate + flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone were tested. Across 3 yrs, CC at termination reduced total weed density by 78 to 99% and total weed biomass by 93 to 99% as compared to weedy fallow. Weed suppression by the CC terminated with glyphosate plus flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone continued for at least 90 days with reduced total weed density of 52 to 80% and total weed biomass reduction by 70% compared to weedy fallow across 3 yrs. No differences in subsequent wheat grain yield between CC treatments and chemical fallow were recorded in 2021-22 and 2022-23; however, in 2023-24, chemical fallow and CC terminated with glyphosate + flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone had greater wheat yield than CC terminated with glyphosate only. These results suggest that integration of spring-planted CC with residual herbicide may help suppress GR B. scoparia and A. palmeri in the CGP.

The main objectives of this study were (1) to determine the effect of fall-planted cover crop (CC) in combination with soil residual herbicides on weed suppression (density and biomass) in subsequent grain sorghum, grain yield, and net returns, (2) to determine the combined effects of spring-planted CC and soil residual herbicide on weed suppression during fallow period, and its impact on subsequent winter wheat yield.

Research

Objective 1:

A field experiment was conducted at Kansas State University Agricultural Research Center near Hays. The soil type at the experimental site was a Roxbury silt loam with a pH of 6.9 and organic matter of 1.6%. The study site was under no-till W-S-F rotation for > 10 years prior to study initiation and had a natural uniform seedbank of GR B. scoparia and Amaranthus palmeri (Kumar, personal observations). All three phases of the W-S-F crop rotation were present each year. After wheat harvest, all plots were sprayed in late July with glyphosate (GLY) (Roundup PowerMax®, Bayer Crop Science, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 1260 g ae ha-1 plus dicamba (Clarity®, BASF Corporation, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) at 560 g ae ha-1. A CC mixture of winter triticale (× Triticosecale Wittm.) (60%)/winter peas (Pisum sativum L.) (30%)/rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) (5%)/radish (Raphanus sativus L.) (5%) was drill seeded into wheat stubble at a rate of 67 kg ha-1 during each fall and terminated in the following spring at the triticale heading stage. The CC planting dates were September 28, October 7, and September 30 in 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively. The CC was terminated on May 13, May 11, and May 22 in 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively. During each spring, four treatments were established: (1) weedy fallow, (2) chemical fallow, (3) CC terminated with GLY alone, and (4) CC terminated with GLY + residual herbicide. In weedy fallow treatment, no CC was planted and no herbicides were applied to control weeds. In chemical fallow treatment, no CC was planted but the plot area was treated with GLY at 1260 g ae ha-1 plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine (ACR/ATZ) (Degree Xtra®, Bayer Crop Science, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 1665/826 g ai ha-1 plus dicamba at 560 g ae ha-1 at the same time as CC termination. For CC termination, GLY at 1260 g ae ha-1 was used, and the residual herbicide was a premix of ACR/ATZ at 1665/826 g ai ha-1. All treatments were established in a randomized complete block design with four replications. During 2020-2021, weedy fallow treatment was not present and there were only three treatments. The individual plot size was 45-m long and 13-m wide each year. During 2021-2022 and 2022-2023 experimental years, the initial chemical fallow plot was sub-divided into two to have both weedy fallow and chemical fallow treatments (45-m long and 6.5-m wide each) for comparison of weed suppression. A sorghum hybrid ‘DKS 38-16’ was planted at a seeding rate of 114,855 seeds ha-1 in rows spaced 76-cm apart on June 9, June 2, and June 15 during 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively. All local agronomic practices for grain sorghum production as recommended by Kansas State University were followed (Ciampitti et al. 2022a). No herbicides were applied in the grain sorghum growing season.

Cover crop biomass, weed density, and weed biomass

Each year, the aboveground shoot biomass of CC was manually harvested from two 1-m2 quadrats from each plot just before CC termination and oven-dried at 72 C for 4 days to obtain dry biomass. Weed density by species (number of emerged seedlings for each species) was recorded from two randomly placed 1-m2 quadrats from each plot at CC termination and at monthly intervals until sorghum harvest (except 2021, where data at 90 days after CC termination was not collected) and aboveground weed biomass was manually harvested and oven-dried at 72 C for 4 days to obtain total weed dry biomass. The average of CC biomass, total weed density, and total weed dry biomass from the two quadrats in each plot at each time were used in the data analysis. The weed species composition was characterized by calculating the relative abundance of each species in each plot using the method described by Thomas (1985) and used by Obour et al. (2022a). Relative abundance was determined using equation 1. Relative density and relative frequency were calculated.

Volumetric water content and grain sorghum yield

The CC effect on soil water content at grain sorghum planting was determined gravimetrically in 30 cm increments up to 150 cm depth. Two soil cores were taken from each plot using a hydraulic probe (Giddings Machine Company) in June 2021 and 2023 before sorghum planting. During 2022, the soil samples were not collected. Soil sample portions from each 30-cm depth were weighed fresh and then dried at 105 C for 4 days to calculate bulk density by dividing the mass of oven-dry soil to the volume of the core. Gravimetric water content was calculated.

Data from both soil cores were averaged to obtain a single soil water measurement that was converted to volumetric water content by multiplying with measured bulk density at each sampling depth. Data for volumetric water content were averaged for both CC treatments as both treatments were the same before termination. Grain sorghum yield was recorded by harvesting each whole plot using a Massey Ferguson 8XP small plot combine harvester (Massey Ferguson, Duluth, GA, USA) and was adjusted to 13.5% moisture content.

Economic analysis

Gross returns were calculated by multiplying the grain sorghum yield and the price of sorghum grain. Net returns were calculated as gross returns minus total variable costs for each treatment for each year. Fixed costs were ignored in this analysis as they were assumed to be consistent across treatments. Four-year average custom rate values published by Kansas State University Land Use Survey Program and the Kansas Department of Agriculture (AgManager 2022) were used for current field operations and input costs. Total variable cost was calculated by adding all the expenses for planting (CC and sorghum), inputs (fertilizer, herbicides, etc., and their application costs), and harvesting. Grain sorghum price for each experimental year was taken from the USDA Economic Research Services market reports (USDA ERS 2023). Prices for grain sorghum were calculated on a per kg basis and ranged from $0.20 to $0.24. All costs and revenue were calculated in U.S. dollars per hectare.

Statistical Analyses

Data were tested for homogeneity of variance and normality of the residuals using the PROC UNIVARIATE procedure in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC). Data for total weed density and total dry biomass were log-transformed to improve the normality of the residuals and homogeneity of variance; however, back-transformed data were presented with mean separation based on the transformed data, whereas the rest of the data met both ANOVA assumptions. All data for CC biomass, total weed density, and total weed dry biomass at each time, volumetric water content, grain yield, and net returns were subjected to ANOVA using PROC MIXED procedure. For CC biomass data, year was considered as fixed effect and replication was considered as random effect. For total weed density and total weed dry biomass data, CC treatment, year, monthly timing, and their interactions were considered as fixed effects whereas replication and their interactions were considered as random effects. For volumetric water content, CC treatment, year, soil depth, and their interactions were considered as fixed effects whereas replication and their interactions were considered as random effects. For data on grain sorghum yield and net returns, CC treatment, year, and their interactions were considered as fixed effects whereas replication and their interactions were considered as random effects. Data for total weed density, total weed dry biomass, volumetric water content, grain sorghum yield, and net returns were analyzed separately for each year because of significant year-by- treatment interaction (P <0.01). Treatment-by-monthly evaluation interaction for total weed density and total weed dry biomass was significant (P <0.001); therefore, data were sorted by monthly evaluation timings using PROC SORT with monthly evaluations treated as a repeated measure. Treatment means were separated using Fisher’s protected LSD test (P < 0.05). The grain sorghum yields were low because of the drought conditions during the study period; therefore, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to obtain net returns to possible grain sorghum yield (700 to 7400 kg ha-1) and prices ($0.09 to $0.24 kg-1) in the region.

Objective 2:

Effect of spring-planted cover crops on weed suppression

A CC mixture of oats (Avena sativa L.) (40%)/barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) (40%)/spring peas (Pisum sativum L.) (20%) was drilled at a seeding rate of 67 kg ha-1 in sorghum stubble in March. The CC was terminated at the oats heading stage (corresponds to Zadoks 53 to 57) every yr. The study was under a randomized complete block design with four replications. Each yr, four treatments were established: (1) weedy fallow, (2) chemical fallow (standard grower practice in the CGP region), (3) CC terminated with glyphosate (GLY) (Roundup PowerMax, Bayer Crop Science, St. Louis, MO) at 1260 g ae ha-1, and (4) CC terminated with GLY at 1260 g ha-1 plus a premix of flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone (FLU/PYR) (Fierce EZ, Valent USA, Walnut Creek, CA) at 106/134 g ai ha-1. The CC was not planted in weedy fallow control plots and no herbicides were applied to control weeds whereas in chemical fallow, no CC was planted but these plots were treated with GLY at 1260 g ha-1 plus a premix of FLU/PYR at 106/134 g ha-1 plus dicamba (Clarity, BASF Corporation, Research Triangle Park, NC) at 560 g ae ha-1 at the same time as CC termination. During 2021-22 experimental period, weedy fallow treatment was not present and there were only three treatments. The plot size was 45-m long and 13-m wide. In 2022-23 and 2023-24, the initial chemical fallow plot was sub-divided into two to have both weedy fallow and chemical fallow treatments (45-m long and 6.5-m wide each) for comparison of weed suppression. Before winter wheat planting, all plots were sprayed in late September with GLY at 1260 g ha-1 plus dicamba at 560 g ha-1. Winter wheat variety ‘Joe’ was planted at a seeding rate of 67 kg ha-1 in rows spaced 19.1 cm apart. Because of low rainfall, winter wheat did not germinate in the fall of 2022, therefore, spring wheat variety ‘WestBred 9717’ was planted in 2022-23 growing season at a seeding rate of 112 kg ha-1. Details for CC planting and termination dates and planting and harvesting dates for winter wheat in each experimental yr are given in Table 1. Weather data, including monthly precipitation and air temperature over the 3-yr study period were obtained from the Kansas State University Mesonet weather station.

Data collection

The aboveground CC biomass was measured by manually harvesting samples from two randomly placed 1-m2 quadrats per plot just before CC termination. The samples were then oven-dried at 72 C for 4 days to determine the dry biomass. Weed density for each species was recorded at CC termination, 30, 60, and 90 days after CC termination (DATe) (except 2021-22, where data at 60 DATe was not collected). Similarly, the aboveground weed biomass was manually harvested and oven-dried at 72 C for 4 days to obtain total weed dry biomass. Data for CC biomass, weed density, and weed biomass were averaged from both quadrats in each plot at each evaluation timing. The relative abundance of each weed species in each plot was calculated following the method outlined by Thomas (1985). Relative density is the number of plants for each species within the quadrat per plot divided by the total number of plants in that sampled quadrat multiplied by 100. Relative frequency is the proportion of quadrats in which the species was present, divided by the frequency of all species in that sampled quadrat, multiplied by 100 (Thomas 1985).

Statistical Analyses

Data were subjected to ANOVA using PROC MIXED procedure in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC). Data were checked for the homogeneity of variance and normality of the residuals using the PROC UNIVARIATE. Data for weed density and biomass were log-transformed to improve the normality of the residuals and homogeneity of variance; however, back-transformed data were presented with mean separation based on the transformed data. For CC biomass data, yr was treated as fixed effect while replication was treated as a random effect. For total weed density and total weed dry biomass data, CC treatment, yr, evaluation timing, and their interactions were considered as fixed effects, whereas replication and their interactions were considered as random effects. For wheat yield, CC treatment, yr, and their interactions were treated as fixed effects, whereas replication and their interactions were considered as random effects. Data for total weed density, total weed dry biomass, and wheat yield were analyzed separately for each yr because of significant yr-by- treatment interaction (P <0.01). Treatment-by-evaluation timing interaction for total weed density and total weed dry biomass was significant (P <0.001); therefore, data were sorted by evaluation timings using PROC SORT with evaluation timing treated as a repeated measure. Treatment means were separated using Fisher’s protected LSD test (P < 0.05).

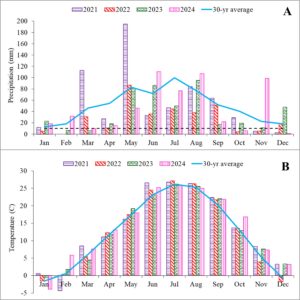

Objective 1:

Variable precipitation amount and frequency were observed at KSU-ARCH during the experimental periods 2020-2021, 2021-2022 and 2022-2023 (Figure 1). The total amount of precipitation received during the CC growing season (September to May) in 2020-2021, 2021-2022 and 2022-2023 was 217, 99, and 130 mm, respectively (Figure 1). The 30-year average precipitation from September to May in the region is 347 mm (Figure 1). No difference was recorded in aboveground CC dry biomass at the time of termination across the years and was 1520, 1130, and 1470 kg ha-1 in 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively, with an average of 1370 ± 123 kg ha-1. During the sorghum growing season (June through October), the total precipitation amount was 256, 171, and 237 mm in 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively (Figure 1). The 30-year average precipitation from June to October in the region is 341 mm (Figure 1).

Total weed density and weed dry biomass

Across three years, four summer annual broadleaf weed species were observed at the study site, including B. scoparia, A. palmeri, Venice mallow (Hibiscus trionum L.), and puncturevine (Tribulus terrestris L.). Based on the relative abundance, B. scoparia and A. palmeri were the dominant weed species across three years (Tables 1, 3, and 4).

2021 growing season. Amaranthus palmeri was the most dominant weed species with a mean relative abundance of >40% across treatments at all monthly evaluation timings (Table 1). Prior to termination [0 days after termination (DAT)], CC reduced the total weed density by 86 to 95% compared to chemical fallow (no herbicide was applied in chemical fallow at this time) (Table 1). However, an application of GLY plus ACR/ATZ plus dicamba in chemical fallow at the time of CC termination reduced weed density at later evaluation timings. Total weed density at 60 DAT was dominated by A. palmeri (relative abundance = 90%) and was significantly greater (approximately 4 times) following the CC terminated with GLY only compared to the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ (Table 1). This would be due to a lack of residual herbicide and CC residue was not enough to suppress the emerging A. palmeri seedlings. At the time of grain sorghum harvest (120 DAT), CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ reduced the total weed density by 50% compared to chemical fallow (Table 1). Consistent with total weed density, CC at termination reduced the total weed dry biomass by 93% compared to chemical fallow (Table 2). The CC terminated with GLY only and with GLY plus ACR/ATZ reduced the total weed dry biomass by 50 to 65% and 42 to 68% at 60 to 120 DAT, respectively compared to chemical fallow. It is interesting to note that no differences were observed in total weed density between chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY only at 120 DAT; however, the same CC treatment significantly reduced the total weed dry biomass by 42% compared to chemical fallow, indicating the suppressive effect of CC on weed growth that would ultimately reduce the weed seed production (Baraibar et al. 2018).

2022 growing season. Mean relative abundance was 46 to 56% for B. scoparia, 0 to 21% for A. palmeri, and 29 to 49% for H. trionum before CC termination (Table 3). Similar to 2021, the CC at termination reduced the total weed density by 90 to 93% compared to weedy fallow. At 30 DAT, the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ reduced the total weed density by 92% compared to chemical fallow and 96% compared to weedy fallow. At 60 DAT, the mean relative abundance was 41 to 75% for B. scoparia, 11 to 53% for A. palmeri, and 12 to 31% for H. trionum among all treatments. The CC termination with GLY only treatment did not produce enough CC biomass to suppress emerging weed seedlings and resulted in 21 more weed seedlings m-2 than the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ at 60 DAT (Table 3). These results indicate the importance of residual herbicide with CC to achieve effective weed suppression. Our findings are consistent with Wiggins et al. (2016), who also concluded that CC alone was not enough for season-long control of GR A. palmeri and suggested integrating residual herbicides to complement the suppressive effect of CC. In the current study, total weed density did not differ between chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ treatments at 120 DAT; however, weed density was nearly 95% lower in CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ compared to weedy fallow and CC terminated with GLY only (Table 3). These results are consistent with Obour et al. (2022a), who previously reported 82% reduction in total weed density with spring-planted CC mixture (oat/triticale/pea) compared to weedy fallow. Petrosino et al. (2015) also reported a 78 to 94% reduction in B. scoparia density with fall-planted CC (triticale/triticale-hairy vetch mixture) compared to chemical fallow in winter wheat-fallow rotation. Similar to weed density reduction, CC at the time of termination provided >95% total weed dry biomass reduction compared to weedy fallow (Table 2). The presence of CC reduces the sunlight penetration to the ground for weed seed germination and also reduces their competitive ability for other resources, thereby resulting in lower weed biomass (Silva and Bagavathiannan 2023; Webster et al. 2016). The CC terminated with GLY only reduced total weed dry biomass by 94% at 30 DAT and 63% at 120 DAT compared to weedy fallow. In contrast, the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ reduced total weed dry biomass by >95% as compared to weedy fallow throughout the sorghum growing season (Table 2). These results indicate the need of residual herbicide in combination with CC for a season-long weed control in grain sorghum. These results are consistent with Whalen et al. (2020), who previously reported that fall-planted CC, including Italian ryegrass [Lolium perenne L. ssp. multiflorum (Lam.) Husnot], oat (Avena sativa L.), and winter wheat provided 38 to 48% weed control without a residual herbicide; however, the control ranged from 72 to 85% under CC with a residual herbicide (sulfentrazone plus chlorimuron) application.

2023 growing season. No weed emergence was observed under both CC treatments at the time of termination (Table 4). In addition, no weed emergence was observed in the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ treatment at 30 DAT. In contrast, a greater weed density of 91 plants m-2 with a relative abundance of 70% for A. palmeri and 30% for B. scoparia was recorded in the CC terminated with GLY only treatment at 30 DAT (Table 4). This increase in A. palmeri and B. scoparia densities under CC terminated with GLY only was probably due to more precipitation within 30 DAT (78 mm, 33% of total precipitation received during the entire sorghum growing season), and lack of any residual herbicide applied at CC termination. Treatments, including the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ and chemical fallow reduced the total weed density by 70% compared to weedy fallow at 90 DAT. Chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ had much fewer weeds (7 to 8 plants m-2) compared to weedy fallow (54 plants m-2 with 73% relative abundance of A. palmeri) at 120 DAT (Table 4). Similar to weed density reduction, CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ resulted in 98%, 46%, and 57% total weed dry biomass reduction compared to weedy fallow, chemical fallow, and CC terminated with GLY only, respectively, at 60 DAT (Table 2). At 120 DAT, the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ and chemical fallow reduced the total weed dry biomass by 83% and 65% compared to weedy fallow. Our results are consistent with Petrosino et al. (2015), who also reported that fall-planted triticale and a triticale-hairy vetch mixture reduced B. scoparia density by 78% and 94%, respectively, and biomass up to 98% compared to chemical fallow. Compared to chemical fallow, the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ provided 5 to 18% more reductions in total weed dry biomass during the entire grain sorghum growing season (Table 2). Wiggins et al. (2016) reported that CC including cereal rye (Secale cereale L.), winter vetch, crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum L.), or winter wheat had less than 65% control of A. palmeri, whereas the same CC in combination with PRE-applied acetochlor or fluometuron resulted in >87% control of A. palmeri.

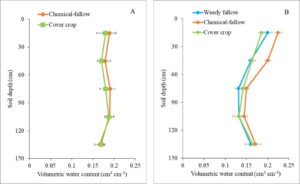

Volumetric water content and grain sorghum yield

The soil water content at sorghum planting is directly related to grain yields in the dryland region (Holman et al. 2023; Obour et al. 2022b). In 2021, fall-planted CC did not affect volumetric water content at grain sorghum planting compared to chemical fallow across all soil depths (Figure 2). This is likely due to greater precipitation at pre- and post-CC termination time (Figure 1). The precipitation received closer to termination or post-termination of CC likely recharged the soil profile thereby diminishing the effects of the growing CC on water availability. Furthermore, the CC residue likely decreased soil water evaporation, increasing moisture storage (Holman et al. 2020, 2021). In contrast, fall-planted CC did reduce the volumetric water content at grain sorghum planting compared to chemical fallow at 0-30 cm and 30-60 cm depths in the 2023 growing season (Figure 2). No differences in the water content were observed between CC and chemical fallow treatments at deeper soil depths. Similar to CC, the weedy fallow treatment also resulted in relatively low volumetric water content (0.16 to 0.20 cm3 cm-3) up to 60 cm soil depth compared to chemical fallow (0.20 to 0.22 cm3 cm-3) indicating soil water depletion by weeds. Holman et al. (2021) reported no difference in the available soil moisture at time of wheat planting between fallow and spring-planted CC left standing during the fallow phase of W-S-F rotation.

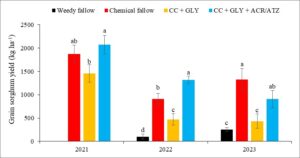

No differences in grain sorghum yields were observed between chemical fallow (1876 kg ha-1) and CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ (2072 kg ha-1) in 2021 and the least grain yield (1456 kg ha-1) was recorded under CC terminated with GLY only (Figure 3). During the 2022 growing season, the overall grain sorghum yield was low due to lower season precipitation (171 mm) compared to 2021 (256 mm). Effective weed suppression (both density and total weed dry biomass) achieved with the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ resulting in a greater grain sorghum yield (1319 kg ha-1) compared to chemical fallow (912 kg ha-1). The CC termination with GLY only suppressed weeds up to 30 DAT (Table 3) and A. palmeri emerging after 30 DAT reduced the grain sorghum yield (472 kg ha-1) (Figure 3). The total precipitation during the 2023 sorghum growing season was 237 mm, but the majority of this precipitation occurred in May and June. There was moisture stress at the boot stage of grain sorghum in September (only 17 mm of rainfall) that resulted in reduced grain yield (432 to 1323 kg ha-1) (Figures 1 and 3). No difference in grain sorghum yield was observed between chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ. The precipitation events in May and June resulted in the emergence of several cohorts of A. palmeri following the CC terminated with GLY only that resulted in competition with grain sorghum and reduced yield (432 kg ha-1) compared to chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ (Figure 3). Based on the precipitation amount and frequency, fall-planted CC had a variable impact on grain sorghum yield. Nielsen et al. (2016) reported a 10% reduction in winter wheat yield following a CC compared to fallow in the W-S-F rotation under the semi-arid CGP. Holman et al. (2022) reported that spring-planted CC (oat grain) after sorghum harvesting in the fallow phase of W-S-F rotation resulted in 29% less available soil moisture at sorghum planting and did not affect the wheat and sorghum yield compared to fallow. In south-central Kansas, Janke et al. (2002) reported no differences in grain sorghum yield following CC (hairy vetch/winter pea) in winter wheat-grain sorghum rotation compared to no CC in years with good rainfall; however, during years with low rainfall, CC establishment was poor, and grain sorghum yield was reduced because of water use by the CC compared to no CC treatment. Eash et al. (2021) also reported that CC had no impact on subsequent crop yields in a very low-yielding environment in Colorado, mainly due to low CC biomass. In this study, the chemical fallow treatment provided more available soil water in one of two years compared to CC treatments prior to sorghum planting. However, this did not translate into a higher grain yield as long as the residual herbicide ACR/ATZ was applied with GLY at CC termination.

Economics analyses

During 2021, the CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ resulted in greater gross returns of $497 ha-1 compared to $450 ha-1 following chemical fallow (Table 5). This was because of better weed control and greater sorghum yield under CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ compared to chemical fallow. However, CC seed and planting costs decreased net returns. Chemical fallow had the highest net returns by $55 ha-1 compared to CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ. Net returns were negative under CC terminated with GLY only because of lower grain sorghum yield than chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ.

Similar to 2021, CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ had greater gross returns ($317 ha-1) followed by chemical fallow ($219 ha-1) and CC terminated with GLY only ($113 ha-1) in 2022 (Table 6). Weedy fallow had the lowest gross returns of $24 ha-1. The net returns for 2022 were negative for all treatments because of low grain sorghum yield which suggests that gross return from grain sorghum was not enough to cover the variable input costs. However, net returns for CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ and chemical fallow were not significantly different (Table 6).

In 2023, the lower grain sorghum yield in CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ resulted in a lower gross return of $181 ha-1 compared to $265 ha-1 in chemical fallow (Table 7). Similar to 2022, the net returns in 2023 were also negative for all treatments. Chemical fallow had less negative net returns (-$65 ha-1) compared to other treatments (-$138 to -$275 ha-1). The cost of CC seed and planting increased the variable cost for both CC treatments and thus resulted in greater negative net returns. Janke et al. (2002) also reported lower net returns with fall-planted CC (hairy vetch/winter pea) before grain sorghum because of lower grain sorghum yield in the years with low rainfall. Obour et al. (2022a) also reported that integrating CC in the dryland cropping system resulted in negative net returns compared to fallow. These results indicate that growing CC only for weed suppression was not profitable compared to chemical fallow.

Based on the sensitivity analysis, a minimum grain sorghum yield of 2000 kg ha-1 was needed to obtain a positive net return ($8 ha-1) following CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ at average grain sorghum price ($0.22 kg-1) during the 3-year study period (Table 8). In the present study, the average grain sorghum yield was low (786 to 1432 kg ha-1). The estimated average grain sorghum yield in western Kansas ranged from 3800 to 5000 kg ha-1 (Ciampitti and Carcedo 2022) therefore, based on this yield scenario, the expected net returns would be $404 to $668 ha-1 following CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ and $506 to $770 ha-1 following chemical fallow at $0.22 kg-1 sorghum price (Table 8). At the lowest grain sorghum price ($0.09 ha-1), a grain yield of 5000 kg ha-1 was expected to cover the cost of CC seed and planting and obtain positive net returns ($18 ha-1) under CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ, however, following chemical fallow, a lower yield of 3800 kg ha-1 was sufficient to obtain positive net returns ($12 ha-1) (Table 8). It is important to note that in the present study, greater weed control was observed following CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ over the grain sorghum growing season compared to chemical fallow. The POST herbicides were not applied in chemical fallow treatment but farmers generally apply POST herbicides to control later emerged weeds and this application would increase the cost of production and decrease the net returns following chemical fallow as compared to CC treatment. At the highest sorghum price ($0.24 ha-1), CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ would result in $48 ha-1 net returns at only 2000 kg ha-1 sorghum yield (Table 8). These results indicate the cost of integrating fall-planted CC in the W-S-F exceeded the benefits of improved weed control.

Results from this 3-year study indicate that integrating a fall-planted CC mixture after winter wheat harvest and terminating it with GLY in combination with residual herbicide before grain sorghum planting in the W-S-F rotation can provide an effective weed suppression in grain sorghum. Results showed that fall-planted CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ reduced total weed density by 34 to 81% and total weed biomass by 45 to 73% compared to chemical fallow over the grain sorghum growing season. No sorghum yield penalty was observed after CC terminated with GLY plus ACR/ATZ. However, due to the CC seed and planting costs, lower net returns were recorded in all three years compared to chemical fallow. These results suggest that growing CC for only weed suppression in the semi-arid CGP would not be profitable at current commodity prices. If the CC were used for hay or forage then net returns would be increased due to alternative use income (Holman et al. 2018, 2021, 2022, 2023; Obour et al. 2022a). However, weed control during the sorghum growing season would likely be affected after the CC residue removal from the field. Therefore, future studies should focus on understanding the timing for the removal of CC residue from the field and its interaction with weed control during the grain sorghum growing period.

Table 1. Total weed density and mean relative abundance of weed species observed in the cover crop (CC) treatments at 0 to 120 days after CC termination (DAT) in 2021a, b

|

Treatments |

Total weed density |

Mean relative abundance |

||||

|

Bassia scoparia |

Amaranthus palmeri |

Hibiscus trionum |

Tribulus terrestris |

|||

|

|

plants m-2 |

-----------------------------%----------------------------- |

||||

|

At 0 DAT |

||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

43 |

a |

43 |

41 |

16 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

6 |

b |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

4 |

b |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 30 DAT |

||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

10 |

a |

38 |

50 |

4 |

8 |

|

CC + GLY |

10 |

a |

12 |

69 |

0 |

19 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

6 |

a |

11 |

53 |

8 |

28 |

|

At 60 DAT |

||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

9 |

a |

24 |

70 |

0 |

6 |

|

CC + GLY |

12 |

a |

10 |

90 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

3 |

b |

10 |

90 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 120 DAT |

||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

4 |

a |

50 |

50 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

5 |

a |

29 |

71 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

2 |

b |

39 |

61 |

0 |

0 |

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine. Means followed by the same letter within a column at each timing are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05

bThe cover crop was terminated on May 13, 2021

Table 2. Total weed dry biomass in the cover crop (CC) treatments at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 days after CC termination during 2021 to 2023 growing seasonsa

|

Treatments |

Total weed dry biomass |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

0 |

30 |

60 |

120 |

0 |

30 |

60 |

90 |

120 |

0 |

30 |

60 |

90 |

120 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------g m-2---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

- |

- |

- |

- |

34 |

a |

107 |

a |

118 |

a |

193 |

a |

263 |

a |

12 |

a |

115 |

a |

388 |

a |

1430 |

a |

1624 |

a |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

15 |

a |

72 |

a |

139 |

a |

147 |

a |

30 |

a |

2 |

c |

3 |

bc |

6 |

c |

12 |

c |

9 |

a |

5 |

c |

13 |

c |

345 |

bc |

560 |

bc |

|

|||||||||

|

CC + GLY |

1 |

b |

41 |

a |

69 |

b |

85 |

b |

1 |

b |

6 |

b |

15 |

b |

41 |

b |

97 |

b |

0 |

b |

44 |

b |

167 |

b |

513 |

b |

1258 |

ab |

|

|||||||||

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

1 |

b |

24 |

a |

48 |

b |

47 |

b |

1 |

b |

1 |

c |

1 |

c |

3 |

c |

10 |

c |

0 |

b |

0 |

d |

7 |

d |

236 |

c |

278 |

c |

|

|||||||||

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine. Means followed by the same letter within a column are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05.

Table 3. Total weed density and mean relative abundance of weed species observed in the cover crop (CC) treatments at 0 to 120 days after CC termination (DAT) in 2022a, b

|

Treatments |

Total weed density |

Mean relative abundance |

||||

|

Bassia scoparia |

Amaranthus palmeri |

Hibiscus trionum |

Tribulus terrestris |

|||

|

|

plants m-2 |

-----------------------------%----------------------------- |

||||

|

At 0 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

58 |

a |

46 |

21 |

33 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

47 |

a |

53 |

18 |

29 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

4 |

b |

51 |

0 |

49 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

6 |

b |

56 |

6 |

38 |

0 |

|

At 30 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

27 |

ab |

56 |

36 |

6 |

2 |

|

Chemical fallow |

13 |

b |

62 |

32 |

6 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

37 |

a |

41 |

54 |

5 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

1 |

c |

62 |

38 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 60 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

28 |

a |

58 |

11 |

31 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

6 |

bc |

47 |

53 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

22 |

ab |

41 |

47 |

12 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

1 |

c |

75 |

25 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 90 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

27 |

a |

80 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

1 |

b |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

13 |

a |

43 |

57 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

1 |

b |

87 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 120 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

19 |

a |

93 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

2 |

b |

91 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

21 |

a |

46 |

54 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

1 |

b |

89 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine. Means followed by the same letter within a column at each timing are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05.

bThe cover crop was terminated on May 11, 2022

Table 4. Total weed density and mean relative abundance of weed species observed in the cover crop (CC) treatments at 0 to 120 days after CC termination (DAT) in 2023a, b

|

Treatments |

Total weed density |

Mean relative abundance |

||||

|

Bassia scoparia |

Amaranthus palmeri |

Hibiscus trionum |

Tribulus terrestris |

|||

|

|

plants m-2 |

-----------------------------%----------------------------- |

||||

|

At 0 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

32 |

a |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

28 |

a |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

0 |

b |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

0 |

b |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 30 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

142 |

a |

37 |

61 |

2 |

1 |

|

Chemical fallow |

12 |

b |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

91 |

a |

30 |

70 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

0 |

b |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 60 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

22 |

a |

13 |

87 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

7 |

b |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

15 |

ab |

25 |

75 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

1 |

b |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 90 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

30 |

a |

16 |

84 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

9 |

b |

10 |

90 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

20 |

ab |

15 |

85 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

9 |

b |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 120 DAT |

||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

54 |

a |

27 |

73 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

8 |

b |

19 |

81 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

22 |

ab |

27 |

73 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

7 |

b |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine. Means followed by the same letter within a column at each timing are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05.

bThe cover crop was terminated on May 22, 2023

Table 5. Economic analyses of grain sorghum after fall-planted cover crop in 2021 growing seasona

|

Variables |

Treatments |

||

|

Chemical fallow |

CC + GLY |

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

|

|

|

-------------------------------$ ha-1------------------------------- |

||

|

Grain sorghum yieldb |

1877.0 |

1456.0 |

2072.0 |

|

Grain sorghum pricec |

0.24 |

0.24 |

0.24 |

|

Revenue from grain sorghum |

450.5 |

349.4 |

497.3 |

|

Gross returns |

450.5 |

349.4 |

497.3 |

|

Variable input costs |

|||

|

Cover crop seed |

0 |

95.7 |

95.7 |

|

Cover crop planting |

0 |

37.1 |

37.1 |

|

Grain sorghum seed |

30.4 |

30.4 |

30.4 |

|

Grain sorghum planting |

32.1 |

32.1 |

32.1 |

|

Fertilizer with application cost |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

|

Herbicide |

126.9 |

25.6 |

95.7 |

|

Herbicide application cost |

13.6 |

13.6 |

13.6 |

|

Grain sorghum harvesting |

60.3 |

60.3 |

60.3 |

|

Total variable cost |

330.0 |

361.5 |

431.6 |

|

Net returns |

120.5 a |

-12.1 b |

65.7 b |

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine. Means followed by the same letter among treatments are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05

bGrain sorghum yield is in kg ha-1

cGrain sorghum price is in $ kg-1

Table 6. Economic analyses of grain sorghum after fall-planted cover crop in 2022 growing seasona

|

Variables |

Treatments |

||||

|

Weedy fallow |

Chemical fallow |

CC + GLY |

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

||

|

|

-------------------------------$ ha-1------------------------------- |

||||

|

Grain sorghum yieldb |

101.0 |

912.0 |

472.0 |

1319.0 |

|

|

Grain sorghum pricec |

0.24 |

0.24 |

0.24 |

0.24 |

|

|

Revenue from grain sorghum |

24.2 |

218.9 |

113.3 |

316.6 |

|

|

Gross returns |

24.2 |

218.9 |

113.3 |

316.6 |

|

|

Variable input costs |

|||||

|

Cover crop seed |

0 |

0 |

95.7 |

95.7 |

|

|

Cover crop planting |

0 |

0 |

37.1 |

37.1 |

|

|

Grain sorghum seed |

30.4 |

30.4 |

30.4 |

30.4 |

|

|

Grain sorghum planting |

32.1 |

32.1 |

32.1 |

32.1 |

|

|

Fertilizer with application cost |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

|

|

Herbicide |

0 |

126.9 |

25.6 |

95.7 |

|

|

Herbicide application cost |

0 |

13.6 |

13.6 |

13.6 |

|

|

Grain sorghum harvesting |

60.3 |

60.3 |

60.3 |

60.3 |

|

|

Total variable cost |

189.5 |

330.0 |

361.5 |

431.6 |

|

|

Net returns |

-165.3 b |

-111.1 a |

-248.2 b |

-115.0 a |

|

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine. Means followed by the same letter among treatments are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05.

bGrain sorghum yield is in kg ha-1

cGrain sorghum price is in $ kg-1

Table 7. Economic analyses of grain sorghum after fall-planted cover crop in 2023 growing seasona

|

Variables |

Treatments |

|||

|

Weedy fallow |

Chemical fallow |

CC + GLY |

CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ |

|

|

|

-------------------------------$ ha-1------------------------------- |

|||

|

Grain sorghum yieldb |

257.0 |

1323.0 |

432.0 |

905.0 |

|

Grain sorghum pricec |

0.20 |

0.20 |

0.20 |

0.20 |

|

Revenue from grain sorghum |

51.4 |

264.6 |

86.4 |

181.0 |

|

Gross returns |

51.4 |

264.6 |

86.4 |

181.0 |

|

Variable input costs |

||||

|

Cover crop seed |

0 |

0 |

95.7 |

95.7 |

|

Cover crop planting |

0 |

0 |

37.1 |

37.1 |

|

Grain sorghum seed |

30.4 |

30.4 |

30.4 |

30.4 |

|

Grain sorghum planting |

32.1 |

32.1 |

32.1 |

32.1 |

|

Fertilizer with application cost |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

66.7 |

|

Herbicide |

0 |

126.9 |

25.6 |

95.7 |

|

Herbicide application cost |

0 |

13.6 |

13.6 |

13.6 |

|

Grain sorghum harvesting |

60.3 |

60.3 |

60.3 |

60.3 |

|

Total variable cost |

189.5 |

330.0 |

361.5 |

431.6 |

|

Net returns |

-138.1 b |

-65.4 a |

-275.1 c |

-250.6 c |

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + ACR/ATZ indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine. Means followed by the same letter among treatments are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05

bGrain sorghum yield is in kg ha-1

cGrain sorghum price is in $ kg-1

Table 8. Net returns to possible grain sorghum yield (700 to 7400 kg ha-1) and prices ($0.09 to $0.24 kg-1) in the regiona

|

Grain sorghum yield |

Net returns |

||||||||||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

CC + GLY +ACR/ATZ |

||||||||||||||

|

0.09 |

0.12 |

0.16 |

0.18 |

0.20 |

0.22 |

0.24 |

0.09 |

0.12 |

0.16 |

0.18 |

0.20 |

0.22 |

0.24 |

|

|

|

kg ha-1 |

-----------------------------------------------------$ ha-1----------------------------------------------------- |

|

|||||||||||||

|

700 |

-267 |

-246 |

-218 |

-204 |

-190 |

-176 |

-162 |

-369 |

-348 |

-320 |

-306 |

-292 |

-278 |

-264 |

|

|

1400 |

-204 |

-162 |

-106 |

-78 |

-50 |

-22 |

6 |

-306 |

-264 |

-208 |

-180 |

-152 |

-124 |

-96 |

|

|

2000 |

-150 |

-90 |

-10 |

30 |

70 |

110 |

150 |

-252 |

-192 |

-112 |

-72 |

-32 |

8 |

48 |

|

|

2600 |

-96 |

-18 |

86 |

138 |

190 |

242 |

294 |

-198 |

-120 |

-16 |

36 |

88 |

140 |

192 |

|

|

3200 |

-42 |

54 |

182 |

246 |

310 |

374 |

438 |

-144 |

-48 |

80 |

144 |

208 |

272 |

336 |

|

|

3800 |

12 |

126 |

278 |

354 |

430 |

506 |

582 |

-90 |

24 |

176 |

252 |

328 |

404 |

480 |

|

|

4400 |

66 |

198 |

374 |

462 |

550 |

638 |

726 |

-36 |

96 |

272 |

360 |

448 |

536 |

624 |

|

|

5000 |

120 |

270 |

470 |

570 |

670 |

770 |

870 |

18 |

168 |

368 |

468 |

568 |

668 |

768 |

|

|

5600 |

174 |

342 |

566 |

678 |

790 |

902 |

1014 |

72 |

240 |

464 |

576 |

688 |

800 |

912 |

|

|

6200 |

228 |

414 |

662 |

786 |

910 |

1034 |

1158 |

126 |

312 |

560 |

684 |

808 |

932 |

1056 |

|

|

6800 |

282 |

486 |

758 |

894 |

1030 |

1166 |

1302 |

180 |

384 |

656 |

792 |

928 |

1064 |

1200 |

|

|

7400 |

336 |

558 |

854 |

1002 |

1150 |

1298 |

1446 |

234 |

456 |

752 |

900 |

1048 |

1196 |

1344 |

|

aCC + GLY + ACR/ATZ indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of acetochlor/atrazine

Objective 2:

The total amount of precipitation received during the spring-planted CC growing season (March to June) was 332, 164, and 184 mm in 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively (Figure 1). No difference was recorded in aboveground CC dry biomass at the time of termination in 2021 and 2022, however, significantly higher CC biomass was recorded in 2023 and was 1240, 1290, and 4060 kg ha-1 in 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively. Although cumulative precipitation in 2021 was high, it was not uniformly distributed. A few major events led to waterlogging and poor CC growth, resulting in lower CC biomass that year.

Total weed density and weed biomass

Bassia scoparia, A. palmeri, E. canadensis, Venice mallow (Hibiscus trionum L.), carpetweed (Mollugo verticillata L.), and grasses mainly tumble windmillgrass (Chloris verticillata Nutt.) were the major weeds at the study site across three yrs. Among all, B. scoparia and A. palmeri were the dominant weed species based on their relative abundance, across three yrs (Tables 2-4).

2021 growing season. Bassia scoparia and A. palmeri were two dominant weed species in 2021 across all treatments and evaluation timings with a relative abundance of 14 to 100% and 23 to 70%, respectively (Table 2). Before termination or 0 DATe, CC reduced total weed density by 97 to 99% compared to chemical fallow. At this evaluation, no herbicide was applied in chemical fallow plots. CC terminated with GLY and GLY plus FLU/PYR reduced total weed density by 74 to 77% and 33% compared to chemical fallow at 30 and 90 DATe, respectively. Consistent with total weed density, CC at 0 DATe reduced the total weed dry biomass by 97% compared to chemical fallow (Table 5). Similarly, at 30 DATe, CC terminated with GLY and GLY plus FLU/PYR reduced total weed dry biomass by 40 to 44% compared to chemical fallow. However, there was no difference in total weed dry biomass between CC treatments and chemical fallow at 90 DATe. These results indicated that over time, CC residue degraded and was no longer able to suppress weeds. Osipitan et al. (2018) conducted a meta-analysis and reported that CC significantly reduced total weed density and biomass at termination and provided early-season weed suppression.

2022 growing season. Bassia scoparia was the dominant weed in 2022 with a relative abundance of 54 to 100% across all treatments and evaluation timings (Table 3). This dominance could be attributed to low precipitation during the growing season and early emergence ability of B. scoparia than A. palmeri. Only 135 mm was received from CC termination to 90 DATe in 2022 compared to 225 mm in 2021 (Figure 1). As B. scoparia is drought-tolerant, it thrived under these conditions; however, lower precipitation probably limited the germination of A. palmeri. Before termination, CC reduced total weed density by 94% compared to weedy fallow (Table 3). At 30 DATe, CC terminated with GLY and GLY plus FLU/PYR, and chemical fallow resulted in a 65 to 95% reduction in total weed density compared to weedy fallow. At 60 DATe, CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR provided 88 to 89% reduction in total weed density compared to weedy fallow or chemical fallow. Similarly, at 90 DATe, CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR resulted in 80%, 72%, and 60% reduction in total weed density compared to weedy fallow, chemical fallow, and CC terminated with GLY only, respectively (Table 3). These results indicate the importance of CC in combination with residual herbicide for reducing the total weed density as compared to chemical fallow. Obour et al. (2022) also reported 82% reduction in total weed density with spring-planted CC mixture (oat/triticale/peas) compared to weedy fallow. Consistent with total weed density, CC reduced total weed dry biomass by 93 to 95% before termination compared to weedy fallow (Table 5). The CC reduced sunlight penetration to the soil, suppressing weed seed germination and their seedlings emergence, competitiveness for resources, ultimately lowering weed biomass (Silva and Bagavathiannan 2023; Webster et al. 2016). At 60 DATe, CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR reduced total weed biomass by 98, 92, and 82% compared to weedy fallow, chemical fallow, and CC terminated with GLY only, respectively. Similarly, at 90 DATe, CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR reduced total weed dry biomass by 70, 36, and 44% compared to weedy fallow, chemical fallow, and CC terminated with GLY only, respectively. A low reduction in total weed dry biomass under CC terminated with GLY only over time indicated that only CC was insufficient to suppress weeds and highlighted a need for residual herbicide with CC. Wiggins et al. (2016) also reported that CC alone was not enough for season-long control of GR A. palmeri and suggested integrating residual herbicides to complement the suppressive effect of CC.

2023 growing season. Bassia scoparia, A. palmeri, and grass weeds (mainly C. verticillata) were dominant in 2023 across all treatments and evaluation timings with a relative abundance of 41 to 100%, 0 to 59%, and 0 to 27%, respectively (Table 4). Prior to termination, CC reduced total weed density by 78 to 80% compared to weedy fallow (Table 4). At 30 DATe, CC terminated with only GLY reduced total weed density by 42% compared to weedy fallow, however, CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR and chemical fallow resulted in 82 to 97% reduction in total weed density compared to weedy fallow. At 90 DATe, both weedy fallow and CC terminated with GLY only had statistically similar total weed density and CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR and chemical fallow had 52 to 71% lower total weed density than weedy fallow. Consistent with total weed density, CC before termination resulted in 97 to 99% total weed dry biomass reduction compared to weedy fallow (Table 5). At 30 DATe, CC terminated with GLY only resulted in 65% reduction in total weed dry biomass compared to weedy fallow, however, CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR increased the total biomass reduction to 95% which was similar to chemical fallow. Similar trend was observed at 60 and 90 DATe. It is important to note that at 90 DATe, there was no difference in total weed density between weedy fallow and CC terminated with GLY only, however, the same CC treatment reduced total weed biomass by 52% compared to weedy fallow. These results indicate the suppressive action of CC on weed growth that would ultimately reduce the weed seed production (Baraibar et al. 2018).

Wheat yield

During the 2022-23 wheat growing season, particularly in October and November 2022, only 10 mm of precipitation was received (Figure 1), which led to poor germination and eventual failure of winter wheat, therefore, spring wheat was planted in the spring of 2023. Wheat grain yield was greater in 2021-22 and ranged from 2789 to 3073 kg ha-1 compared to 2022-23 and 2023-24, where wheat grain yield ranged from 570 to 952 kg ha-1 (Table 6). The greater winter wheat grain yield in 2021-22 compared to 2023-24 might be due to higher precipitation in 2021-22 at critical wheat stages, including the jointing stage (Mar - Apr) and booting to heading stages (April - May) (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in wheat yield between CC treatments and chemical fallow in 2021-22 and 2022-23, however, in 2023-24, chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR resulted in greater yield followed by CC terminated with GLY only and least yield was recorded in weedy fallow. Holman et al. (2022) reported that fallow replacement in W-S-F rotation with spring-planted CC had no significant effect on wheat yield when conditions were either extremely dry with poor yields or very wet with above-average yields.

Results from this study indicate that integrating spring-planted CC mixture after grain sorghum in the W-S-F rotation and terminating it with GLY plus FLU/PYR herbicide can provide weed suppression up to 90 DATe. Before termination (mid to late June), spring-planted CC reduced total weed density by 78 to 99% and total weed biomass by 93 to 99% compared to weedy fallow. It is critical for early-emerging weeds like B. scoparia and A. palmeri which can start emerging in March-May (Dhanda et al. 2024; Dille et al. 2017; Kumar et al. 2018). With time, CC residue started to degrade and at 90 DATe, CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR reduced total weed density by 52 to 80% and total weed dry biomass by 70% compared to weedy fallow across yrs. No differences in wheat grain yield between CC treatments and chemical fallow were recorded in 2021-22 and 2022-23, however, in 2023-24, chemical fallow and CC terminated with GLY plus FLU/PYR had greater yield than CC terminated with GLY only. It is important to note that under the low wheat yield scenario observed in the present study, net returns could become negative. This is because the reduced returns from wheat yield may not be sufficient to offset the costs of CC seed and planting, as highlighted in our previous study (Dhanda et al. 2025b). Future studies should focus on integrating other weed control methods along with CC to control late-emerging weeds.

Table 1. Planting and termination dates for cover crop and planting and harvesting dates for grain sorghum and wheat during 2020-22, 2021-23, and 2022-24 seasons at Kansas State University Agricultural Research Center near Hays, KS.

|

Crop |

Operation |

2020-22 |

2021-23 |

2022-24 |

|

Grain sorghum |

Planting |

June 14, 2020 |

June 9, 2021 |

June 2, 2022 |

|

Harvesting |

Oct 18, 2020 |

Nov 4, 2021 |

Oct 26, 2022 |

|

|

Cover crop |

Planting |

March 9, 2021 |

March 16, 2022 |

March 3, 2023 |

|

Termination |

June 24, 2021 |

June 23, 2022 |

June 13, 2023 |

|

|

Wheat |

Planting |

October 7, 2021 |

April 10, 2023* |

October 2, 2023 |

|

Harvesting |

July 11, 2022 |

July 6, 2023 |

July 10, 2024 |

*Winter wheat planted on September 30, 2022, did not germinate, therefore, spring wheat was planted

Table 2. Total weed density and mean relative abundance of weed species observed in the cover crop (CC) treatments at 0, 30, and 90 days after CC termination (DATe) in 2021-22 at Kansas State University Agricultural Research Center near Hays, KSa.

|

Treatments |

Total weed density |

Mean relative abundance |

|||||

|

Bassia scoparia |

Amaranthus palmeri |

Grass |

Mollugo verticillata |

Erigeron canadensis |

|||

|

|

plants m-2 |

-----------------------------------%---------------------------------- |

|||||

|

At 0 DATe |

|||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

74 |

a |

43 |

23 |

14 |

13 |

7 |

|

CC + GLY |

1 |

b |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

2 |

b |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 30 DATe |

|||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

57 |

a |

14 |

41 |

14 |

9 |

22 |

|

CC + GLY |

15 |

b |

31 |

45 |

4 |

4 |

15 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

13 |

b |

27 |

48 |

0 |

2 |

24 |

|

At 90 DATe |

|||||||

|

Chemical fallow |

6 |

a |

54 |

39 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

|

CC + GLY |

4 |

a |

28 |

70 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

4 |

a |

32 |

66 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + FLU/PYR indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone. Means followed by the same letter within a column at each timing are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05

Table 3. Total weed density and mean relative abundance of weed species observed in the cover crop (CC) treatments at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days after CC termination (DATe) in 2022-23 at Kansas State University Agricultural Research Center near Hays, KSa.

|

Treatments |

Total weed density |

Mean relative abundance |

|||||

|

Bassia scoparia |

Amaranthus palmeri |

Hibiscus trionum |

Grass |

Erigeron canadensis |

|||

|

|

plants m-2 |

-----------------------------------%---------------------------------- |

|||||

|

At 0 DATe |

|||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

630 |

a |

94 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

604 |

a |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

36 |

b |

76 |

24 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

35 |

b |

93 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 30 DATe |

|||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

120 |

a |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

37 |

b |

54 |

5 |

11 |

10 |

21 |

|

CC + GLY |

42 |

b |

92 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

6 |

b |

89 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

|

At 60 DATe |

|||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

44 |

a |

84 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

|

Chemical fallow |

40 |

a |

87 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

|

CC + GLY |

30 |

ab |

88 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

5 |

b |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

At 90 DATe |

|||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

85 |

a |

92 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

Chemical fallow |

61 |

a |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

43 |

ab |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

17 |

b |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + FLU/PYR indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone. Means followed by the same letter within a column at each timing are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05

Table 4. Total weed density and mean relative abundance of weed species observed in the cover crop (CC) treatments at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days after CC termination (DATe) in 2023-24 at Kansas State University Agricultural Research Center near Hays, KSa.

|

Treatments |

Total weed density |

Mean relative abundance |

|||||

|

Bassia scoparia |

Amaranthus palmeri |

Hibiscus trionum |

Grass |

Erigeron canadensis |

|||

|

|

plants m-2 |

-----------------------------------%---------------------------------- |

|||||

|

At 0 DATe |

|||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

116 |

a |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

104 |

a |

92 |

7 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

25 |

b |

91 |

7 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

23 |

b |

75 |

23 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

At 30 DATe |

|||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

67 |

a |

62 |

35 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

2 |

c |

41 |

59 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

39 |

b |

68 |

28 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

12 |

c |

75 |

23 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

At 60 DATe |

|||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

52 |

a |

67 |

27 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

22 |

b |

82 |

10 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

|

CC + GLY |

49 |

a |

50 |

47 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

32 |

b |

90 |

9 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

At 90 DATe |

|||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

56 |

a |

47 |

26 |

0 |

27 |

0 |

|

Chemical fallow |

16 |

b |

85 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY |

61 |

a |

49 |

34 |

0 |

16 |

0 |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

27 |

b |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

aCC + GLY indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate only and CC + GLY + FLU/PYR indicates cover crop terminated with glyphosate plus a premix of flumioxazin/pyroxasulfone. Means followed by the same letter within a column at each timing are not different according to Fisher’s protected LSD at P < 0.05

Table 5. Total weed dry biomass in the cover crop (CC) treatments at 0, 30, 60, and 90 days after CC termination during 2021 to 2024 growing seasons at Kansas State University Agricultural Research Center near Hays, KSa.

|

Treatments |

Total weed biomass |

|||||||

|

0 |

30 |

60 |

90 |

|||||

|

|

-------------------------------g m-2------------------------------- |

|||||||

|

2021-22 |

||||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

- |

|

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Chemical fallow |

34 |

a |

62 |

a |

- |

- |

68 |

a |

|

CC + GLY |

1 |

b |

37 |

b |

- |

- |

73 |

a |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

1 |

b |

35 |

b |

- |

- |

59 |

a |

|

2022-23 |

||||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

58 |

a |

95 |

a |

116 |

a |

125 |

a |

|

Chemical fallow |

53 |

a |

16 |

b |

24 |

b |

58 |

b |

|

CC + GLY |

4 |

b |

5 |

bc |

11 |

b |

66 |

b |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

3 |

b |

1 |

c |

2 |

c |

37 |

c |

|

2023-24 |

||||||||

|

Weedy fallow |

194 |

a |

224 |

a |

500 |

a |

626 |

a |

|

Chemical fallow |

115 |

a |

3 |

c |

58 |

c |

170 |

c |

|

CC + GLY |

6 |

b |

79 |

b |

188 |

b |

303 |

b |

|

CC + GLY + FLU/PYR |

2 |

b |

11 |

c |

58 |

c |

188 |

c |