Progress report for GNC23-380

Project Information

Flea beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) are major agricultural pests, feeding on Brassica vegetables, greens, and solanaceous crops. Their larvae are minor root pests, while adult foliar feeding leaves characteristic shotgun patterned damage, often significantly reducing crop quality and yield. Current control measures include insecticides and exclusion netting to prevent adult feeding. However, due to the small size of these insects, fine netting poses additional issues, including temperature extremes and exclusion of beneficial insects. Additionally, netting does not protect the crop from newly emerging adults from the root zone. While chemical pesticides can knock down flea beetle populations, there are few options for organic growers when controlling this pest.

Biological control is an option for growers who focus on sustainable farming methods and reducing pesticide use. Currently, several commercially available species of entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) are recommended for control of flea beetle larvae. However, this technique fails to address the high mobility of adult beetles, which emerge from overwintering locations and disperse into the crop. Thus, applications of EPNs at the crop root zone alone have little effect on foliar damage. Because of this overwintering behavior, trap cropping to intercept adult beetles seeking hosts in early spring has also been used. Trap crops alone may reduce feeding damage on the main crop but fail to reduce pest populations without pesticide application. While some organic pesticides are registered for use against flea beetles, efficacy when treating the trap crop alone remains low. These outcomes suggest that management of flea beetles must provide control within the crop and in the landscape, attacking multiple life stages.

This project aims to develop a technique for controlling flea beetles in high tunnel Brassica crops using a combination of EPNs and trap crops. EPN applications for flea beetle control will be two-fold, treating both the larvae in the soil within the tunnel, as well as adults that encounter wild mustard trap crops grown outside the tunnel. Evaluation will assess persistence of EPNs through waxworm bioassays on collected soil samples and assess flea beetle control through sticky card data and observations of beetles as well as foliar damage. This project will introduce a novel and more comprehensive method of pest control for flea beetles in organic and low-input production, targeting multiple life stages of the pest and thus providing more complete crop protection. Establishment of trap crops and soil management practices to increase persistence of EPNs can decrease labor and expenses dedicated to control flea beetles.

Anecdotal accounts from surveyed growers in Indiana identify flea beetles as one of the most economically important, damaging, and difficult to control insect pests in high tunnel production systems. Successful implementation of a system that decreases pest pressures from flea beetles in multiple life stages would benefit growers across the state and region. From the results of the project, growers who struggle with control of flea beetles will gain knowledge on the use of EPNs for biological control as well as a deeper understanding of the flea beetle life cycle, behavior, and additional means of control beyond typical exclusion or treatment within the crop system. With this new knowledge, growers may be inclined to focus attention on the landscape outside of their high tunnels and main crop fields, identifying potential locations to include trap crops and to apply EPNs. Growers that traditionally use pesticides to control flea beetles may be interested in trying a newer, low-input approach. Outcomes can be measured by the proportion of growers that intend or take action to implement biological control measures outside of the high tunnel. Growers may also be inclined to alter the landscape surrounding high tunnels, to either effectively practice trap-cropping, or to eliminate locations of refuge for pests that are not easily managed. Outcomes will be assessed quantitatively by distribution of surveys to growers to indicate interest in implementing this practice in and around their high tunnels.

Objective 1: Assess efficacy of Brassica juncea trap crop in combination with three commercially available EPN species.

Objective 2: Cater low-input multi-generation control of flea beetles to grower high tunnels.

Research

Preliminary Work: Crop Selection

The cash crop used in these experiments is Flash collard greens (Johnny’s Selected Seeds, ME; Brassica oleracea). This crop was selected due to its relative heat tolerance and tendency to be slow to bolt, making it compatible with the high tunnel environment. B. oleracea is also a species with lower glucosinolate composition, creating a stark contrast between the cash and trap crop, thus increasing the odds of success in differential attraction of flea beetles. Mighty Mustard® Pacific Gold (Johnny’s Selected Seeds, ME; Brassica juncea) is advertised by the manufacturer as a cover crop that may additionally be effective as a trap crop for crucifer-feeding flea beetles (Pacific Gold Blend 2019). Of the Brassica species listed, B. juncea has the second highest concentration of allyl isothiocyanate according to Cole (1976), and the highest concentration of phenylethly-isothiocyanate, two known flea beetle attractants (Table 1). Wild turnip (B. rapa) was originally planned as the trap crop, but additional research suggested that beetles would be more attracted to a B. juncea trap crop over longer distances due to the chemical composition of the plant.

Table 1. Comparison of species-specific concentrations of allyl isothiocyanate and phenylethyl-isothiocyanate, two glucosinolate products identified as attractants for Phyllotreta adults by Wittstock et al. (2003) for six Brassicas as outlined in (Cole, 1976). n/a = data was not provided.

|

Species |

Allyl isothiocyanate concentration (ug/g) |

Phenylethyl-isothiocyanate concentration (ug/g) |

|

Brassica chinensis (now B. rapa subsp. chinensis) |

1 |

5 |

|

B. juncea |

24 |

7 |

|

B. napus |

n/a |

1 |

|

B. nigra |

32 |

4 |

|

B. oleracea |

1 |

2 |

|

B. rapa |

n/a |

3 |

Objective 1 Methods:

1.1: Affirm trap crop choice with greenhouse feeding and oviposition bioassays.

Hypothesis: Adult flea beetle feeding and preference will be correlated with host chemical composition, specifically that isothiocyanate concentration makes a host plant more attractive.

Prediction: Both species of flea beetles will preferentially feed and oviposit in juncea over B. oleracea.

Experimental Design: Trays of Flash Collards (B. oleracea) and Pacific Gold mustard (B. juncea) were seeded in the greenhouse. When plants were approximately 4 weeks old, they were transplanted into 4-inch round pots filled with potting medium. Pots were labeled with plant type, EPN treatment, and time duration (Table 2). 16 plants (one of each treatment combination) were randomly placed per bug dorm, with 6 total dorms used. 75 field collected flea beetles were placed in each bug dorm. 3 dorms contained Phyllotreta striolata, and 3 contained P. cruciferae. Bug dorms containing plants and beetles were kept under greenhouse conditions and pots were be watered as needed while minimally disrupting plants and soil.

Table 2. Variables manipulated and treatment levels used in feeding bioassays.

|

Variable |

Levels |

|||

|

Plant |

B. oleracea |

B. juncea |

|

|

|

EPN Treatment |

S. carpocapsae |

S. feltiae |

H. bacteriphora |

Control |

|

Duration |

4 days |

10 days |

|

|

Data collection: Data were collected at 4 and 10 days after beetle introduction. At each date, the number of beetles observed on each plant was recorded, and the percent of foliar damage was assessed. After 4 days, half of the 16 pots per bug dorm (those assigned the 4-day treatment) were removed from the bug dorms. Data were collected from the remaining 8 pots per dorm after 10 days. Upon removal, plants were placed in trays and transferred to an incubator. Plants continued to be watered by filling the trays with about one centimeter of water to be taken up by plants through holes in the bottom of pots. After 2 weeks to allow for hatching and maturation of flea beetle offspring, EPN treatments were applied. Approximately 500 infective juveniles in 1mL of water were pipetted directly into the soil of each pot. Following EPN application, a perforated bag was secured over the top opening of each pot containing the plant. Plants were incubated and watered from below until emergence of adult flea beetles. The number of beetles that emerged from each plant into the perforated bag were recorded. Beetle emergence was used as a proxy for oviposition (controls) and EPN efficacy.

1.2: Model low-input control of flea beetles in collard greens using a high-glucosinolate mustard trap crop and entomopathogenic nematodes.

Experimental Design: 12 high tunnels at Meigs Purdue Agricultural Center were used for the experiment. Flash (F1) collard greens (Johnny’s Selected Seeds) were seeded per distributor instructions in 72 cell trays in the greenhouse in late March. One week after germination, seedlings were thinned to one per cell. Once seedlings had two pairs of true leaves, or after about 4 weeks, and when outside daytime temperatures were consistently above 10°C, they were transplanted into the high tunnels. All tunnel beds were covered with black plastic mulch to prevent weeds. Seedlings were transplanted in four plots of ten plants each in one South-facing external bed of each of the 12 tunnels. Tunnels were assigned one of four treatments: a control, where there is no EPN application and no trap crop, a treatment with just a trap crop, but no EPN application, a treatment with EPN applied in the soil around the cash crop but no trap crop, and a treatment with both the trap crop and EPN application. Treatment assignment were blocked by tunnel type. Tunnel treatments were randomized within those blocks across the 12 tunnels, with three tunnel replicates per treatment. For tunnel treatments requiring a trap crop, Mighty Mustard® Pacific Gold was be seeded in the greenhouse several weeks prior to anticipated emergence of overwintering flea beetles. The trap crop was seeded directly into 2-gallon trade pots containing a 1-inch layer of pea gravel at the bottom to help with water drainage and to provide weight and support to the pot to prevent the trap crop from being damaged by wind when placed outside. On top of the gravel, the pots were filled with BM7 potting mix, and the top 1 inch of the soil was a BM2 germination mix, in which the mustard seeds were directly placed. Before anticipated beetle emergence from overwintering, trap crops were placed directly adjacent to the bed of collards, outside the tunnel wall (Figure 1).

To prevent the need for weeding around the trap crops, a layer of landscape fabric was laid down under the pots. Trap crops were replaced as needed. Trap crops will be irrigated by extending a drip line outside of the tunnel to lay over the top of the pots, allowing irrigation at a rate and frequency matching the beds. EPN (Koppert, US) was to be applied to the respective beds and trap crop through drip irrigation at a rate of 500,000 ij/m². Applications were to occur bi-weekly for the duration of the experiment.

*Note: EPN applications did not take place in 2024, but this experiment is planned to be repeated in 2025. See Results and Discussion below.

Data collection: Data collection occurred weekly for the duration of the experiment. First, yellow sticky cards were set in each cash crop plot at plant height (four per tunnel), replaced weekly. Tunnels with trap crops also had four sticky cards placed in the trap crop at approximate plant height. Relevant insects on yellow sticky cards were identified to family, and all flea beetles or other Brassica feeding insects were identified to species. Timed visual observations counted the number of flea beetles observed in one randomly selected collard crop plot per tunnel recorded in one minute. For tunnels with a trap crop, 1-minute observations were taken in the trap crop row as well.

References

Cole, R. A. (1976). Isothiocyanates, nitriles and thiocyanates as products of autolysis of glucosinolates in Cruciferae. Phytochemistry, 15(5), 759–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94437-6

Wittstock, U., Kliebenstein, D. J., Lambrix, V., Reichelt, M., & Gershenzon, J. (2003). Chapter five Glucosinolate hydrolysis and its impact on generalist and specialist insect herbivores. In J. T. Romeo (Ed.), Recent Advances in Phytochemistry(Vol. 37, pp. 101–125). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-9920(03)80020-5

1.1 Preliminary Data: Data collected from repeating these experiments twice in summer 2024 support B. juncea as a trap crop for collard greens (B. oleracea), as the average number of beetles observed as well as the proportion of damage was significantly higher on B. juncea at both time points (Figure 2). Data presented are summed across both flea beetle species, as trends did not differ. However, significantly more beetles emerged from B. oleracea than B. juncea, though EPN surprisingly had no effect (Figure 3).

Discussion: The collected data affirm the use of B. juncea as a trap crop for Phyllotreta flea beetles as the feeding preference was evident. However, the alarming result of the lack of effect of EPN treatment on beetle emergence has lead to additional questions that I aim to address in the future of this project. First, though with the different treatments replication of control groups is low, there may be an oviposition preference that is the opposite of the feeding preference for the beetles. A better understanding of movement of gravid females between the trap crop and cash crop can better inform placement of EPN treatments to control soil dwelling larvae. Additionally, EPN products that are marketed for control of flea beetles may not actually be effective in this system. Some literature suggests that the nematocidal properties of brassica crops that are used as green manures for plant parasitic nematode control can actually deter EPN as well. Further, much of the existing research on EPN for flea beetle control uses lab reared strains, rather than the commercial products available for growers to purchase. Future greenhouse experiments will assess whether exudates from healthy brassica plants or secondary metabolites released due to plant damage negatively impact EPN. I also plant to assess whether beetle diet (i.e. type of brassica they are feeding on - with varying chemical composition) impacts ability of EPN to infect and kill the host insect.

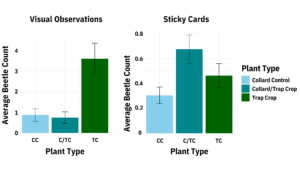

1.2 Preliminary Data: The 2024 trap crop study data showed that based on visual observations, far more beetles were found in the mustard trap crop compared to the collard greens, corroborating the greenhouse bioassay data. However, the sticky cards placed in collard plots with an adjacent trap crop collected the most flea beetles (Figure 4). I hypothesize that this difference could be due to beetle movement towards the attractive yellow sticky cards, rather than an appropriate representation of beetle communities when they are feeding.

Discussion: Overall, in 2024 the beetle populations were surprisingly low in and around the high tunnels. Despite neighboring fields reporting devastating flea beetle damage, total counts remained low. Because of this, no EPN were applied to the tunnels in 2024, as the low populations, particularly early in the season when females would be ovipositing, would make it hard to determine an effect. In 2025, I anticipate that many of these late-season arriving beetles will overwinter in the area around the tunnels, and populations will be high enough to justify EPN applications.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

In 2024, I participated in a field day at Throckmorton Purdue Agricultural Center located in Lafayette, IN, with an audience of growers, agricultural professionals, and academics. This included a demonstration of research and in collaboration with other researchers showcased pest management practices in high tunnel specialty crop systems. Last year, I also published an insect spotlight article in Purdue University's Vegetable Crops Hotline Newsletter. Data from this project were shared to an academic audience at the Entomological Society of America annual meeting held in Phoenix, AZ in November 2024. Additionally, these data were shared to an audience of growers at the 2025 Indiana Small Farm Conference held in early March.

Project Outcomes

Transitioning into the second year of this project, my goal is to end this summer with more concrete recommendations for growers in terms of using trap cropping, EPN, and other low-input management practices in general. Specifically, I want this product to help growers to incorporate these concepts into their existing integrated pest management plans. At the 2025 Indiana Small Farm Conference held in Danville, IN, I gave an extension talk and networked with growers to recruit farmer participants in my research. I am in the process of expanding my network of growers to increase the reach of my work, and also diversify the environments that I implement these pest management tools in, as each farm and even high tunnel proves to be a unique system. I will reach out to an existing network of high tunnel growers in the state to increase farmer participation in the study. Ultimately, optimizing the informed use of these key tools will help growers to minimize the costs associated with managing their high tunnel crops. Beyond using a trap crop for pest control, I hope to demonstrate the value of sacrificing space on-farm for non-crop plants, particularly those that provide some other ecosystem service. Anecdotally, the mustard trap crops used at our research farm were excellent resources for a number of pollinators, namely syrphid flies, which can provide pollination as well as biological control services.

Through my research using trap crops, one of the messages that I try to get through to growers I work with and attendees at talks and demonstrations I give is that there can be economic benefits to allocating space for these non-crop plants. I have worked with growers to figure out ideal placement of these non-crop resources to provide maximum ecosystem services. Working with a farmer in Northeast Indiana, we devised a system to use regrowth of early-harvested brassica plants as a trap to prevent entry of beetles into a cash-crop that was still several weeks out from harvest. I hope to continue to cater to individual needs of farmers to make these methods and tools something that is easy and economical for them to use year after year.

Through this project, and specifically through disseminating results and speaking with growers, I have learned a lot about what sustainable agriculture looks like from a different perspective. I realized that we as scientists have idealized ideas about regenerative, "green," or low-input practices, but can sometimes be caught in a disconnect with the growers themselves who are, more than anything, concerned with the well-being of their crop, which is their livelihood. I have learned that sustainable for them doesn't just mean that there is optimal protection for the environment and minimized use of insecticides, but sustainable for themselves; feasible, easy to carry out, and able to turn a profit off of.