Final report for GNC24-391

Project Information

Title: Barriers to Adoption of Prairie Strips: Farmer Perspectives

Agriculture is a primary land use in the Midwest, United States and Michigan benefits from a diverse fruit and crop industry. To maintain productivity, Michigan farmers employ agricultural management practices, including synthetic pesticides, fertilizers, and tillage for weed and pest management. However, intensive agriculture has led to a decline in wildlife habitat and biological diversity. One potential solution is the establishment of prairie strips, or perennial prairie plantings within row-crop agriculture that enhance ecosystem services such as soil health, pest predation, and pollination. Prairie strips uniquely benefit both the farming community and agricultural systems by reducing the need for intensive agricultural practices, while providing necessary habitat for ecosystem health and resiliency.

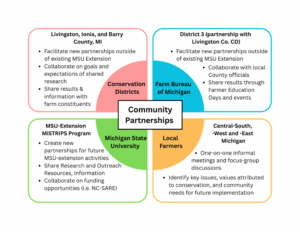

However, adoption among farmers in Michigan remains low. I proposed community engaged research project to address the question: What are the opportunities and barriers to adoption of prairie strips in Michigan? I collaborated with Conservation Districts and the Michigan Farm Bureau in three Michigan counties to host interviews and focus groups. By partnering with local organizations for this community engaged project, we targeted conservation-oriented farmers and utilized a “place-based” approach for discussion and data collection. Interviews and focus groups took place throughout fall 2024 and spring 2025, based on farmer availability. The development, implementation, and evaluation of the interviews and focus groups included input from partnering Conservation Districts and the Michigan Farm Bureau to better reflect the priorities within their districts. I worked with MSU-Extension MiSTRIPS and other MSU students and faculty to carry out presentations and group facilitation. Summary and analysis of these discussions will be published and presented to Conservation Districts, Michigan Farm Bureau, MSU Extension, and participating farmers.

Over the course of three focus-groups, both online and in-person, a diverse set of farmers including livestock, crop, and fruit or vegetable farmers participated in the discussion, interviews, and survey questions. Although a majority of farmers (>70%) had heard of prairie strips or plantings and many expressed interest, the issue remains that farmers need government or local support for both the establishment and maintenance of conservation practices. The focus groups further served to introduce Conservation Districts as a supporting partner for material, equipment, funding, or knowledge on conservation and farming practices in their districts.

This community-engaged research project will benefit both the farming community and the academic community. Through this project and after, I hope to better understand what continues to encourage or prevent farmers from adoption of conservation practices such as prairie plantings or strips. While the qualitative analysis of this project will inform the academic community on next steps, the results will also be shared with local farming communities to support the Conservation District's efforts to increase sustainable agricultural practices within their districts.

By engaging directly with farmers, this project aimed to improve a) the understanding of the opportunities and barriers to adoption of prairie strips in Michigan on the part of MSU researchers and extension; and b) the access to knowledge and resources on prairie strips as a conservation practice on Michigan farms on the part of participating farmers. Through a series of interviews and focus groups, farmers discussed prairie strips and gained access to a community of conservation-oriented farmers and programs with similar goals. By collaborating with MiSTRIPS, farmer participants also gained access to a larger conservation network.

The long term, sustainable outcomes of this project will include the change in Michigan’s agricultural landscape to include both more conservation-oriented farmers and diversity in farming practices. By engaging with farmers directly to identify opportunities and addressing place-based barriers to adoption of prairie strips, this project will lead to an increase in the number of Michigan farms and acreage enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) of the US Farm Bill, in particular CRP-43 which provides monetary incentives for farmers converting previously arable land to prairie strips. Presenting my research at Conservation District and Farm Bureau meetings, as well as farmer education days held by partnering organizations will continue to facilitate trust and partnerships between MSU researchers, MSU-extension, Conservation Districts, and participating farmers. Lastly, to adapt for an inconsistent climatic and economic future, this project aimed to facilitate the adoption of a “resilient mindset” through place-based, regenerative agricultural management on Michigan farms.

Cooperators

Research

Community Focus Groups

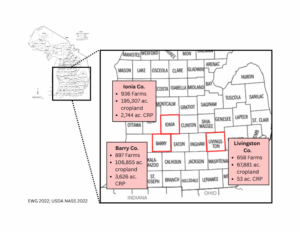

In the spring 2025, I conducted a community-engaged research project with conservation districts in Livingston, Barry, and Ionia, Michigan counties and hosted focus groups with rural farmers not currently in MSU-affiliated programs (Figure 2). All three counties are primarily rural with high cropland acreage, but relatively low acreage enrolled in the USDA Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). The literature suggests a mixed-methods approach using both quantitative and qualitative data to address factors related to farmer perspectives (Prokopy et al. 2019). I chose to work with Conservation Districts (CDs), as they are a federally-funded subdivision of state government with elected board members that represent local Michigan counties and provide natural resource management information, funding, and resources to community members (MDARD 2024). By working with Conservation Districts, I was able to “purposefully identify” (Stratton 2024) a small sample of farmers per district with conservation-oriented mindsets or current practices (i.e. already adopted no- or reduced-tillage, cover cropping practices). Furthermore, by working in districts independent of one another, I was able to encourage a “place-based” approach to qualitative data collection, ensuring trust and familiarity within groups to help facilitate discussion (Prokopy et al. 2019). This further allowed me to compare the focus groups among counties (i.e. “sites”) to generate quantitative data. By working with both Conservation Districts and individual farmers, I employed multiple levels of community input to the research process. The focus groups are at the “inform” and “consult” stage, whereas the Conservation Districts are at the “involve” and “collaborate” stage (IAP2, 1999; Vaughn and Jacques 2020) (Figure 3).

One of the key “principles of community engagement” described by McCloskey et al. (2010) is to form community relationships and build trust. Prior to conducting the focus groups, I attended several Livingston County Conservation District meetings and a District Three Farm Bureau meeting in 2023-2024 to propose the project and gain initial feedback; I attended several Livingston County meetings and events from 2022-2025. Several members of the Livingston CD were also board members of the Farm Bureau, and the two groups often collaborate on events. I also conducted two informal visits and interviews with two local farmers in 2023. These 1–hour meetings helped define my project goals and identify key conservation issues for different types of farms and were the foundation for my funding applications to support this community-engaged research project. I also introduced myself to the Conservation District boards in Ionia and Barry counties in the fall of 2024 during their monthly meeting. Furthermore, I was invited to present on prairie strips and implementation at the Farmer Education Day hosted by the Livingston CD and District 3 Farm Bureau in February 2025, where ~ 50 farmers attended, and several Michigan State University professors and extension agents presented on current research.

Focus groups took place throughout February and March 2025. Each focus group was approximately 1-2 hours and took place from 9-11am at a local facility; Livingston County was conducted at the Livingston Educational Service Agency; Barry County at the Pierce Cedar Creek Institute; and Ionia County at the MSU Clarksville Research Station. All participants were provided with refreshments throughout the event (as was advertised) and reimbursed for attending ($100 gift card) (Figure 4). Focus groups were primarily discussion-based. Folders with printed agendas, consent forms, resources and information were handed out to each participant. Pre- and post-surveys were used to evaluate participant knowledge of prairie strips and will remain anonymous with only necessary information for later analysis (age, type of farm, rental land or owned, new or generational farmer, etc.). Participants started with a pre-survey that addressed their knowledge of prairie strips as a regenerative agriculture resource and the benefits and disadvantages of prairie plantings. This was followed by a short presentation on prairie strips, including a breakdown of implementation costs and how CRP-43 is designed to assist landowners with prairie strip installation and maintenance. After the presentations, we hosted brief breakout groups to facilitate discussion on topics related to a) both the advantages and disadvantages of prairie strips; b) based on the presentations, what are the barriers or bridges to adoption on your farm; and c) questions or concerns about prairie strips that were not addressed in the presentations. Each group summarized their findings on a large sheet of paper, which was collected for later qualitative analysis. After the discussion session, participants were asked to complete a post-survey with the same questions as before, to record how their answers may have changed after both the information and discussion session, with an option for further comment.

The Ionia County focus group information was shared to social media and available to a larger audience than the other county groups. Given that many farmers had reached out online to ask for a virtual session, the Ionia County focus group was held as a hybrid event, with attendees both in-person and online. Participants were provided access to an online version of the pre- and post-survey and could join focus group discussions via the online chat. Due to the nature of sharing the focus group information online, it was necessary to remove bad-faith actors who were not local farmers or who had not fully participated as was requested. This resulted in a total of 21 online attendees approved for reimbursement and their information from the surveys used in this study.

Farmers included in these discussions came from diverse backgrounds, including landowners or renters, all crop or livestock types, new and generational farmers, and all ages or genders. Overall, we hosted a community of farmers aged 22-62 including both men and women (more men attended the virtual session, and more women the in-person sessions). Farms ranged from livestock, beef, and poultry to vegetables and fruit orchards, both organic and conventionally produced. This mix of perspectives allowed for discussion on the flexibility needed for prairie strip integration and management.

Initially, 79% of the participants had heard of prairie strips but only a few had established them on their farm. When asked how to describe regenerative agriculture before the workshop, responses focused on the long-term health of the farm for future generations and the need for diverse, organic practices. The post-survey responses for this question specifically identified the need for soil health and crop resiliency, and the inclusion of ecosystem health. Further, when asked to describe prairie strips or plantings in the pre-survey, the responses were varied and vague or alluded to other conservation practices like riparian buffers. Post-survey responses highlighted the biodiversity of prairie strip grasses and flowers, and ecosystem services. Many of the participants are interested or actively involved in conservation efforts on their farms but had minimal knowledge about why or how those practices benefited the larger landscape or contributed to crop resiliency in the face of changing climates.

IRB Statement

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board (STUDY00010415) on 6/6/2024. This study has been determined to be exempt under 45 CFR 46.104(d) 2ii.

REFERENCES

Basso, B. et al. (2019). Yield stability analysis reveals sources of large-scale nitrogen loss from the US Midwest. Sci Rep 9: 5774. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42271-1

Brown, V. A. (2008). Leonardo’s vision: A guide to collective thinking and action. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Comito, J., Haub, B. C., & Stevenson, N. (2017). Field Day Success Loop. The Journal of Extension, 55(6), Article 29. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.55.06.29

Drobnak, R., Baziari, F., Swinton, S., Charles, C., Wilke, B., Schultheis, E., LaPorte, Sprunger, C., Tyndall, J., Gammans, M., and Doll, J. (2024). Budgeting for Prairie Strips. Michigan State University. https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/budgeting-for-prairie-strips.

International Association for Public Participation. (1999). Spectrum of participation, https://www.iap2.org/page/pillars.

Licht, M. A., & Martin, R. A. (2007). Communication Channel Preferences of Corn and Soybean Producers. The Journal of Extension. 45(6), Article 11. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol45/iss6/11

Marquart-Pyatt, S. (2024). Farmers Perspectives on Prairie Strips: Early Results from the Panel Farmer Survey. [presentation given 2/12/2024]

McCloskey et al. (2010). Principles of Community Engagement Second Edition. Presented at “Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium”. NIH Publication No. 11-7782.

Prokopy, L.S. et al. (2019). Adoption of agricultural conservation practices in the US: Evidence from 35 years of quantitative literature. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 74(5): 520-534.https://doi.org/10.2489/jswc.74.5.520.

Schon, D.A. (1995). Knowing-In-Action: The New Scholarship Requires a New Epistemology. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 27(6), 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1995.10544673.

Stratton S.J. (2024). Purposeful sampling: advantages and pitfalls. Prehosp Disaster Med. 39(2):121–122.

Tscharntke, T., Klein, A.M., Kruess, A., Steffan-Dewenter, I. and Thies, C. (2005). Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity – ecosystem service management. Ecology Letters. 8: 857-874. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00782.x.

USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). (2021). Rank in U.S. agriculture by selected commodities, 2020. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Michigan/Publications/Annual_Statistical_Bulletin/stats21/Economics.pdf.

Vaughn, L. M., & Jacquez, F. (2020). Participatory Research Methods – Choice Points in the Research Process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13244.

A key outcome of the focus group discussion was to identify the opportunities and barriers to prairie strips, specifically on small Michigan farms. Farmers were positive about the environmental benefits of prairie strips, including increasing biodiversity and ecosystem services; they also were interested in using low-yielding areas for conservation to save money. The barriers or disadvantages identified during the workshops included the agronomic challenge of maintaining the prairie, potential pest/weed spillover to the crop, and the economic risk they take in converting arable land to conservation habitat. Taking land out of production, and the seeds, equipment, and labor involved are not achievable without federal support.

One of the most interesting take-aways from the focus groups was the need for better communication, trust, and relationship-building. In general, “farmers want to do good” but feel pressured to continue generational practices or cannot afford to change practices without support. Farmers place value in trust and long-term relationships, but the high turnover of staff or instability of funding resources at local CDs and NRCS is not encouraging and does not support their needs.

Discussion and Conclusions

Conservation practices that support biodiversity or ecosystem services require strategic placement and flexibility. The ‘intermediate landscape-complexity hypothesis’ described by Tscharntke et al. (2005) distinguishes habitats with 2-20% semi-natural or non-crop habitat within the landscape as benefiting the most from conservation interventions. Identifying interested farmers and landowners within applicable intermediate-landscapes to establish prairie strips in Michigan is one of many strategies to increase biodiversity of natural predators and to support more diverse landscapes overall. Research conducted by Michigan State University scientists have used remote sensing technology to identify low-yielding areas of arable lands (Basso et al. 2019). Across 10 Midwest, US states, ~26% of sampled corn fields (7.8 million ha) were low-yielding and could benefit from conservation interventions. Conservation practices such as perennial prairie strips provide necessary non-crop habitat to support biodiversity and service provision through protection from disturbance, alternative prey or floral resources, and overwintering habitat. MSU extension MiSTRIPS have created partial budgets to assist aspirational farmers with prairie strip implementation that suggest long-term profits from converting crops producing at <50% yield (Drobnak et al. 2024).

Engaging with farmers to meet their needs for pest management can be difficult given social and economic constraints (Prokopy et al. 2012). However, despite the literature on the benefits of prairie strips and federal support for prairie strip establishment under the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), adoption remains low in Michigan. Future research on prairie strips and their establishment must collaborate with local farmers to better meet their needs for soil health, pollination or pest control, and economic support, and must encourage the active participation of the farming community.

Farmer engagement is necessary for future agricultural studies, yet few scientific studies implement mixed-methods approaches or reciprocal sharing of ideas, data management, and results required by community-engaged scholarship. It is more common for researchers to conduct an experiment and provide a demonstration day to share the results with stakeholders and interested farmers (i.e. outreach but not engagement) (Comito, Haub, & Stevenson, 2017). In part, because studies show that demonstration days are preferred by farmers (here, corn and soybean) to learn from both professionals in agriculture and fellow farmers implementing those practices (Licht and Martin, 2007). There is an infinite amount of information available to farmers, and demonstration days are useful for identifiying the most applicable practices supported by both local farmers and university research.

As described in Brown (2008), this type of “western knowledge” focuses on specialized (interdisciplinary and professional), and organization thinking (administrative or strategic). Community-engaged scholarship encourages the combined specialized and organizational knowledges typical of university researchers with individual (lived experience), local (shared experiences), and holistic (value or purpose) knowledge found within communities (Brown 2008). Organizational knowledge and institutional ways of thinking are also barriers to scientific researchers conducting community-engaged scholarship. Schon (1995) best describes this as the “dilemma of rigor and relevance” or academic and practical knowledge. The scientific process and science as an institution are constantly evolving – community-engaged scholarship contributes to this process and provides greater flexibility in the development and dissemination of knowledge. This form of scholarship requires reflection before and after the research is conducted and takes into consideration what the true “issue” is based on community feedback and not only prior scientific research.

Every farm is different, whether by size, crop diversity, management, or the surrounding agricultural landscape both culturally and physically. Based on the responses from the focus groups and the most current research, farmers are amenable to establishing prairie strips for climate resiliency, encouraging native pest predation and pollination, and soil regeneration. However, they need the continued support from government funding to establish these practices or cover the loss they will initially experience from converting arable lands for conservation habitat. To best understand how scientific research influences on-ground practices, future scientists must partner with farmers and growers to conduct on-farm trials and community-led discussion. Feedback from such efforts and partnership will improve our understanding of best practices for broader application and adoption of conservation interventions in agriculture. The issue does not lie with individual farmers, but rather social pressures and “norms” for practices in their communities and support from large entities like USDA or MDARD. It is not an easy solution, and will require continued partnership, research, and engagement for years to come.

Educational & Outreach Activities

Participation summary:

The results of this community-engaged research project have not been finalized. I will work with members of the Ionia, Barry, and Livingston County Conservation Districts and District Farm Bureau to share the findings at community meetings or Farmer Education Days. I will also share any results or pictures from the event (with permission) on CD-associated websites or social media to encourage the adoption of prairie strips on Michigan farms. I am currently preparing a short (5-10 page) report on the results of the qualitative analysis and description of the focus groups to be given to each of the Conservation Districts and distributed at their discretion. Furthermore, I plan to present this data at local, regional, and national conferences attended by farmers, industry professionals, and academics, such as Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Market Expo (GLEXPO). The data collected from these discussions will be published according to the interests of the Conservation Districts, Farm Bureau, and participating farmers. This will include publication in open-access journals of the qualitative analysis and methods, such as Environmental Entomologist, Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, Journal of Extension, or Agriculture and Human Values.

An appendix outlining the project goals and methods was included in my dissertation, and this project was incorporated into the written portfolio for my Graduate Certificate in Community Engagement at Michigan State University. My dissertation is published and available via ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (https://www.proquest.com/pqdtglobal?accountid=12598).

This project has been presented at two university-based forums, including the MSU Kellogg Biological Station (KBS) Graduate Fellows Symposium, and the KBS Long-term Ecological Research (LTER) Demonstration Day. I further presented on both this project and prairie strip research at the Livingston County Farmer Education Day in February 2025 to ~50 farmers (hosted by the Conservation District and District 3 Farm Bureau).

Prior to conducting the focus groups, the surveys and discussion questions were shared with each Conservation District for editing and approval. I also shared the survey and project materials with outreach specialists at both Kellogg Biological Station and MSU for initial feedback. Altogether, 30 farmers participated in the focus groups.

Project Outcomes

This study furthers the available knowledge on the barriers and advantages to prairie plantings and other farm-based conservation strategies by using a community-engaged scholarship (CES) framework to design, implement, and disseminate results to both the farming and academic community in southern Michigan. This research demonstrates the value of CES in academic studies, in particular to agricultural studies where participation from the farmer is necessary. Furthermore, this research offers on-the-ground results and farmer perspectives that could direct future policymakers and agricultural advisors at local and state-levels in developing funding opportunities or programs that support regenerative agroecosystems. Overall, this project provided resources and information on prairie strips and plantings, and access to local resources (such as Conservation Districts) to rural farmers across southern Michigan and expanded the current network of farmers actively participating with MSU extension programs.

This project provides farmer perspectives on the implementation of conservation practices in southern Michigan. From this work, we know that farmers are presented with a multitude of conservation practice options and require further assistance in identifiying which best meets their needs, their local environment, and the parameters of their farm. Further, we know that farmers are aware of the negative impacts of farming and are willing to integrate resiliency into their practices but lack the opportunity or funds to implement them. However, focus group discussions also described community and trust as key factors in farmer relationships. The high turnover of federal agriculture agents and limited availability of their time has led to feelings of distrust or frustration between agents and their farmer clientele and may impact whether farmers participate in conservation practices.

This study has provided a valuable opportunity for farmer perspectives to be heard by the academic community and for important conservation resources and information to be disseminated to a larger rural audience.

The community partners for this project were federal units (Conservation Districts), rather than individuals, which meant there were necessary limitations to the amount of time they could spend advertising and collaborating on this project. However, CDs also have connections with farmers in their county and have developed trustful relationships. Unfortunately, CDs are not all the same and some counties have higher funding, more members, and a dedicated board that can spend time on extension projects. For example, the Livingston County CD has very limited funding, no central office or facility, and a limited board with full-time jobs. I found that the members of my local board were more willing to partner and work with me but given their limited capacity, were unable to take on extra responsibilities related to the project. Whereas the larger districts in Ionia and Barry delegated this project to subcommittees and required greater collaboration for project updates and approval. Moving forward with partnership-driven research, it is recommended to identify the strengths of each community partner and allocate goals appropriately to meet everyone’s needs and still collect valuable data.