Final Report for GNE15-109

Project Information

Vermont’s largest sector of agriculture, the dairy industry, has increasingly relied on Latino/a migrant farm labor. Due to systemic barriers, including isolation and a lack of a year-round visa program, these farm workers are unable to access basic needs, including nutritious, fresh, and culturally relevant food. The objective of this research project has been to better understand the barriers to food access. Outcomes of the research project are a tool that aids farm owners in supporting food access and food security for their employees. Additionally this research has supported an on-going community based food access project called Huertas (kitchen garden in Spanish).

Introduction:

Vermont prides itself on being a national role model in developing innovative models for community-supported, ecologically responsible agricultural practices. However, Vermont’s largest sector of agriculture, the dairy industry, has increasingly relied on Latino/a migrant farm laborers who face significant challenges. Due to a lack of a year-round agricultural visa program, most farm workers on Vermont’s dairy farms are unable to receive proper documentation. This circumstance has a significant impact on migrant workers, particularly those living and working closer to the border, as those areas fall within federal jurisdiction of U.S. immigration enforcement. In these borderlands, surveillance is intensified and so the pressure to be invisible is heightened. The current availability of agricultural visas is limited to seasonal migrant farmworkers, and because dairy is year-round work, farmworkers in the dairy industry are barred from accessing proper documentation. Undocumented migrant farmworkers on Vermont’s dairy farms, particularly up north, often describe their life here as encerrado, which translates to “locked in”, “enclosed”, or “penned up”. Because they are unable to be in the public sphere, for fear of deportation, they must rely on others for food. Increased patrolling along the northern border results in extreme isolation, fear, and the inability to access basic human rights. For migrant workers on Vermont’s dairy farms, just taking a trip to the grocery store is to risk deportation. Most farmworkers rely on their bosses or a third party to go to the grocery store for them.

“I have to think about what I have here, because if I don’t have things, now that I can’t go to the store whenever, I have to cook with what I have… In Mexico there are many stores nearby, so if we need something, we go to buy it, but here, no. Here I have to buy for 15 days’ worth, and if we run out of ingredients, I have to do what I can…. here we can buy the food that we want… The problem is that we cannot leave.”

-Juana, age 40, from Mexico (from a 2015 interview)

This research project developed a bilingual grocery catalogue that farm workers can use to know what is available and how to ask for it. In addition to enhancing the manner in which food is brought to the farm, this research project supported an ongoing project called Huertas, which supports farm workers in cultivated small vegetable gardens on the farms where workers are living. This project supports access to fresher and culturally familiar vegetables and herbs.

This research project collaborated with UVM Extension and the UVM Anthropology and Food System departments to better understand and support food access for migrant farmworkers on dairy farms.

- Understand current gaps in food access for Latino/a farm workers on Vermont’s dairy farms

- Quantify food insecurity among Latino/a farm workers and identify effective and realistic approaches to increased food access

- Support and develop initiatives to provide farm workers with greater access to healthy, culturally familiar food

Cooperators

Research

This research is based upon more than four years of community-based research looking at food access among Latino/a farm workers in Vermont, conducted in collaboration with Dr. Teresa Mares of the anthropology department at the University of Vermont. This research was approved by the University of Vermont’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Confidentiality of all research participants has been maintained throughout the project and all names used in my research are pseudonyms.

QUALITATIVE METHODS

This research draws principally upon ethnographic fieldwork, which included over 400 hours of participant observation and analysis of 61 pages of typed field notes. I draw upon 30 in-depth interviews, with farmworkers (n=20) and community stakeholders (n=10) conducted by Dr. Mares and/or myself over the past two years. To analyze these interviews, Dr Mares and I conducted a preliminary round of hand-coding on the translated interview transcripts by reading through the interviews and marking themes and concepts that seemed to be repetitive and/or related to our research questions. Next, we met to discuss our hand coding, and to ensure inter-coder reliability. To develop a codebook we divided our codes into major codes and minor codes, and grouped related themes. For example, a major code might be “Migration and Citizenship” and the subcodes are “Migration Experience”, “Citizenship”, “Motivation for Migration”, “US-Mexico border”, “Border”, and “Border Patrol”. Once we developed a codebook, I loaded all of the transcripts into ATLAS.ti and read through them again, re-coding based on the code book we had developed. The ATLAS.ti software is a computer program used for qualitative data analysis. It is useful because you are able to easily change codes and/or groupings, easily organize quotations based on themes, and export the data to another person who is using the software. In addition to the interviews conducted by Dr Mares and/or myself, I analyzed 15 interview transcripts conducted in 2006 through the Vermont Folklife Center for an exhibit called the Golden Cage Project, which includes interviews with dairy farm owners and migrant farmworkers. These interviews provide temporal perspective, providing a window into some of the perceptions and experiences of farm workers and farm employers in Vermont a decade ago. The Golden Cage interviews were coded using the same codebook in ATLAS.ti as the in-depth interviews.

QUANTITATIVE METHODS

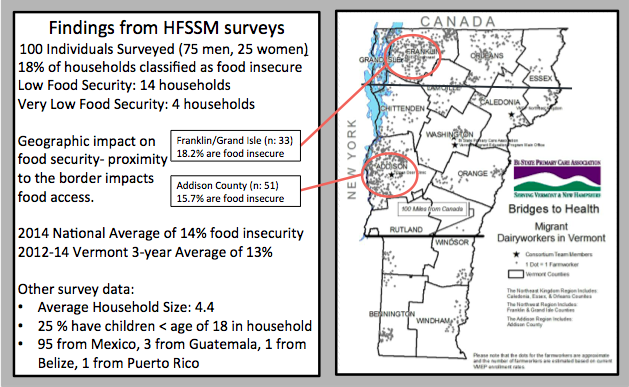

Dr. Mares and I conducted 100 of the USDA Household Food Security Survey Modules (HFSSM) within migrant households. It is important to have this baseline data, and to be able to draw comparisons with national data. Food security is commonly defined by the USDA as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy lifestyle” (Coleman-Jensen et al, 2015). The current tool for measuring food (in)security is the USDA Household food security survey module (HFSSM). The HFSSM is a standardized, rapid questionnaire that goes up to 16 questions, which ask whether a household has enough money to meet their food needs. Since the development of the Spanish-language version of the HFSSM by Harrison et al (2002), research has shown that Latino/a immigrant farm worker communities are experiencing levels of food insecurity significantly higher than the national average (Borre et al., 2010; Kilanowski & Moore, 2010; Quandt et al., 2004; Sano et al., 2010; Weigel et al., 2007; Wirth et al., 2007). These research studies have focused on seasonal workers and in states that have longer histories of hiring Latino/a migrant farmworkers. These studies showed that farmworkers experience food insecurity between 3 and 4 times the current national average (Mares et al., 2013). This means that according to previous researchers, 45-82% of farmworker households were food insecure, with a disproportionate number reporting “very low food security” (Borre et al., 2010; Kilanowski & Moore, 2010; Weigel et al., 2007; Wirth et al., 2007). In Vermont, there had been no published research on food (in)security among Latino/a migrant farm worker populations prior to our work.

OBJECTIVE 1. Understand current gaps in food access for Latino/a farm workers on Vermont’s dairy farms

Findings: Impacts on Farm worker Food Access in Vermont

- Absence of a year round visa

- Proximity to the US-Canada border

- Dependence on third party for food access

- Rural isolation

- Busy work schedules

- Language barrier

- Lack of transportation/mobility

The major reoccurring theme in my research has shown that border proximity has an impact on farmworker food access. Farmworkers, particularly those who live and work in Northern Vermont, face the constraints of their close proximity to the U.S.-Canada border, including higher levels of surveillance. The region 100-miles south of the U.S.-Canada border falls under federal jurisdiction. Vermont is 157 miles long, north to south, and so, this zone includes 90% of Vermont residents. However, the 25-mile region along the border is called “primary operating domain”, where the presence of border patrol and enforcement is higher (ACLU Vermont, 2013). After 9/11, the number of border patrol agents doubled, northern border patrol employees were sent to the US-Mexican border to be trained, the northern border was militarized, and surveillance was increased. Peter Andreas (2005) calls this transition the “Mexicanization” of the U.S.-Canadian border. This increased militarization along the border causes extreme isolation for Latino/a migrant farmworkers, forcing them to remain invisible, particularly the closer they live to the U.S.-Canada border. This has had an impact on the ways in which farmworkers are able to (or unable to) access food.

In northern Vermont, food access strategies for farmworkers are dictated by a fear of being in public spaces. Data found in the USDA food security surveys that Dr. Mares and I conducted (n=100) found that in central Vermont’s Addison county, 15.7% of farmworkers are food insecure (n=51), while among those living in Northern Vermont’s Franklin county (which falls in the “primary operating domain”) 18.2% were found to be food insecure (n=33). This discrepancy speaks to the challenge of accessing food, particularly in the northern border regions. Farm owners, who also live in fear of border patrol, encourage farmworkers not to be in public spaces, and commonly do the grocery shopping for their employees. Typically, at least one farmworker in a household is literate in Spanish and will write out a grocery list, and a farm owner or manager will buy groceries every fifteen days or two weeks (McCandless, 2010). A 2010 survey by Naomi Wolcott-MacClausland through UVM Extension found that in border counties 96.2% of migrant farmworkers rely on someone else to go to the store for them (Wolcott-MacClausland, 2010). UVM Extension developed a bilingual food list that assists farmworkers in communicating what they want to the person going to the store for them. Particularly in border regions, farmworkers rely on the farm owner, manager, or someone else to buy the groceries for them. Challenges with this system include barriers in language and literacy, a lack of knowledge about what foods are available, and limited choice in fresh, culturally specific foods.

OBJECTIVE 2. Quantify food insecurity among Latino/a farm workers and identify effective and realistic approaches to increased food access

After years of ethnographic research and participant observation, Dr. Mares and I knew that Vermont had unique challenges to food access because of isolation, border proximity, and busy work schedules. As we embarked on the study to determine baseline food security through the HFSSM, which was used in these other studies, we expected to see the results of farmworkers in Vermont to reflect the disproportionately high levels of food insecurity. We also had the expectation that the survey module may not capture the lived reality of food access. We observed over years of working with farmworkers that having enough money, which is the main indicator in the survey module, was not generally the main barrier to accessing food. The rapid 16-question survey only asks if a household has enough money to access healthy nutritious food, and does not record other barriers such as transportation or busy work schedule. Therefore, we paired the surveys with in-depth interviews and ethnographic methods, as to understand some of the complexity in accessing food, particularly in border regions.

After completing the HFSSM (n=100) the results showed that of the farmworkers on Vermont’s dairies, 18% were classified as food insecure, which does not parallel with other studies. As I attempt to reconcile the differences in this data, there are a few answers that emerge. First, dairy work is desirable employment for farmworkers because of the stability it can offer. In-depth interviews with farmworkers in Vermont who have worked other seasonal jobs around the U.S., affirm that dairy work is preferred to other migrant jobs, because the work is year-round and offers a higher wage than most seasonal migrant work. Also, they are often given housing, which is a major issue for a lot of seasonal labor jobs. This data was further supported after my meeting with Mary Jo Dudley, Director of the Cornell Farmworkers Program, who works with farmworkers in dairy work as well as seasonal vegetable and fruit, and livestock industries. Mary Jo Dudley conveyed that in a state where there is a large population of migrant farmworkers across many agricultural sectors, dairy work is the most stable and often sought after by migrant farm workers. Because Vermont has such a small population of farmworkers, most of whom are working in dairy, this is likely to be a contributing factor in the relatively low percentage of farmworkers experiencing food insecurity.

However, the fact that migrant farmworkers in Vermont are experiencing relatively average food security levels according to the HFSSM, while our qualitative data shows that they are experiencing unique obstacles in this non-traditional destination, indicates that there is a need to examine the metrics and indicators being used to measure food access. This mismatch in quantitative and qualitative data comes back to the HFSSM itself. Often, when conducting the questionnaire, respondents said that yes, they have enough money to buy the food that they need, however they are unable to go to the store because they are afraid of la migra or they do not have transportation or the work schedule is so busy. The survey module cannot capture this feedback, because it only asks about having enough money. For example, in the HFSSM, Lourdes was recorded as having high food security. Yet, as previously discussed, we know that Lourdes is unable to leave the barn apartment where she lived with her husband, two children, and other workers. The survey instrument focuses on economic barriers to food access, but excludes other barriers, including a lack of reliable transportation, busy work schedules, and a fear of border patrol.

Further, the module classifies a “household” as those who are living together under one roof. However, in the case of migrant farmworkers, the household is not restricted to the physical space where they are living while providing labor in exchange for income. In the case of many farmworkers we have surveyed, they lived together with other workers, but they were also supporting households back home. And so, while they may have enough money to purchase food for themselves, they are often sending large portions of their income to Mexico to support medical, food, housing, and education expenses for their spouses, children, parents and extended family. Within the “household” (as classified by the HFSSM on the dairy farm in Vermont) there are often three or four young, single men who are living together, but do not necessarily share money, food, or resources with one another. The HFSSM is unable to capture the complexity of these household structures, which are often elongated geographically in the case of transnational immigration.

OBJECTIVE 3. Support and develop initiatives to provide farm workers with greater access to healthy, culturally familiar food

Based on the qualitative and quantitative data acquired through my research, I focused on two main initiatives that enable farmworkers to access health, culturally familiar food- Huertas and the Bilingual Supermarket Catalogue.

HUERTAS

Alongside my research looking at food access and food security among farmworkers in Vermont, I have also coordinating an applied gardening project called Huertas. Huertas, meaning kitchen garden in Spanish, is an applied gardening and community based food access project. This gardening project germinated in response to the variety of pressures on undocumented farmworkers in northern Vermont: pressure to be invisible, fear of border patrol, and lack of mobility. The garden project offers a reprieve where migrant farmworkers can access fresh vegetables and herbs that remind them of home. Through connecting farmworkers with volunteers, materials, and the permission from the dairy owners to plant these gardens, Huertas aims to address the disparities in access to nutritious food while simultaneously bridging the barriers of isolation and social inequalities. The SARE grant enabled me to support the efforts of Huertas in several capacities. I was able to directly coordinate and plant gardens with farmworkers, supervise interns and volunteers involved in the project, and present to community groups and university classes about Huertas and the problems farmworkers face related to food access.

BILINGUAL SUPERMARKET CATALOGUE

The bilingual grocery catalogue was developed throughout the summer of 2016 with the guidance and support of staff from UVM extension. The grocery guide is based upon the findings from my research (above) that farmworkers in the border region experience heightened levels of food insecurity and rely on someone else to go to the grocery store for them. The guide shows images of the foods available at the supermarkets in northern Vermont where third parties do the shopping for farm workers. This guide was brought to farmworkers living in the border region who rely of third parties to do their grocery shopping for them for feedback. The feedback from farmworkers was incorporated into the catalogue, until a final version was created and printed through the support of this NESARE grant. Fifty-five catalogues were printed and the template was shared with staff at UVM extension so that they can edit and distribute in the future.

HUERTAS

The SARE grant enabled me to support the efforts of Huertas in several capacities. I was able to directly coordinate and plant gardens with farmworkers, supervise interns and volunteers involved in the project, and present to community groups and university classes about Huertas and the problems farmworkers face related to food access. According to ethnographic research, we have found that Huertas participants appreciate the project for it's varied benefits including recreation/community, economic, cultural, and nutritional benefits.

Feedback from interviews:

“Now I go outside and listen to the birds sing. I feel more free, like I’m in the fields in my village. The memories of what it was like there come back.” –Lourdes, age 33, from Mexico

“Well, here my favorite is my work, no more than this. And beyond that, I like to plant tomatoes, chilies, radish, squash, this is not to sell products, it is just for the home… I like when people come to visit, to feed them. It is not a business. This food, it is a gift of the earth, for everyone. It is not meant to be a business.” –Tomás, age 62, from Mexico

“Because we have the garden, there are fresher vegetables: fresher tomatoes, all of the food is more fresh. And during the winter, well what we find at the grocery store is mostly refrigerated or in the cooler and sometimes we do not find the same things as what we plant.” -Yasmin, age 33, from Mexico

“Having a huerta here I’m saving money. I’m saving when I get tomatoes, everything that I plant - the onions, tomatoes, chilies, all of it that I sow, so then I don’t have to buy it at the store, so there I am saving money. And also I am also cultivating it, everything is so fresh, in the time that it is good, in the summer, and it’s really nice to know I will have it from the plant and I bring it in and cook it” –Fernando, age 53, from Mexico

In the 2015 growing season I supported and facilitated the planting of 43 gardens on dairy farms with farm workers. The primary focus geographically was in border counties, where there are greater challenges in accessing consistent healthy and culturally appropriate food. In 2015 we successfully coordinated two “food days”. One was help in Franklin County and the other was hosted at Sterling College. On these days, farm workers gathered to cook food, celebrate the garden harvest, learn new recipes, and learn about preservation techniques. Everyone who came to the events went home with canned jars of salsa.

In the 2016 growing season we planted 35 gardens and successfully coordinated three "food days", two in Franklin County and one in the Northeast Kingdom. With the support of the NESARE grant I was able to extend my work supporting Huertas and work with the coordination team to hire interns and ensure the sustainability of the project once I finish graduate school and am no longer involved in the project.

BILINGUAL SUPERMARKET CATALOGUE

The bilingual supermarket catalogue is currently in the process of being distributed to farmworkers in the border region of Vermont by UVM extension. The catalogue went through several phases of feedback, in which research assistants and I brought the catalogue to farmworkers in northern Vermont for feedback. A version was shared with staff at UVM Extension, so that it can continue to be edited and distributed.

Other impacts and results include the continuation of this research by my advisor Dr Teresa Mares, who will continue to work with farmworkers on issues of food access. Dr Teresa Mares is currently writing a book that draws upon the research that I have contributed to.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

- Student Research Conference 4/28/16

- Rohatyn Center’s Fourth Annual International and Interdisciplinary Conference titled Food Insecurity in a Globalized World: The Politics and Culture of Food Systems.

- Forthcoming: Book to be published out of this conference in 2017, which I will contribute a chapter called Seed Sent from Home

- Classroom presentations:

- PHIL: Ethics of Eating (est. 50 students)

- CDAE: World Food, Population and Sustainable Development (Fall est. 280 students/spring 200 students)

- NFS: Farm to Table (est 70 students)

- NR: Race and Culture (est 140 students)

- Middlebury Food Geography (est 25 students)

- Addison Hunger Council 6/7/16

- NESARE poster presentation 7/26/16

- Thesis Defense 8/24/16

- Forthcoming: Chapter in Food Across Borders, I will be a co-author in this edited volume

- Bilingual Grocery Guide

Project Outcomes

N/A

Farmer Adoption

N/A

Areas needing additional study

- Impact of the food purchasing guide

- Trends in detentions, raids, and deportations in Vermont's northern regions

- Re-examining the HFSSM measurement tool

- Tax contributions of undocumented farmworkers and it's impact on the local community in VT

- The work of Migrant Justice