Final report for GNE16-140

Project Information

The rapid development of shale gas across Pennsylvania’s rural farm and forestland prompted communities in the region to quickly seek information that could guide their leasing decisions in a way that they hoped would increase profits, improve quality of life, and protect the natural resources of their region. Many of the private landowners living in affected areas turned to landowner coalitions as a tool for information sharing and collective bargaining. Landowner groups have played an instrumental role in shale gas development in the Marcellus region. In Pennsylvania alone, nearly forty landowner groups have formed to gain collective bargaining power in negotiations with industry representatives. Little research has been done to evaluate the outcomes attained by landowner coalitions in Pennsylvania or explore how they have affected shale gas development in the region. Using primary data collected throughout a five-county region in Northeastern Pennsylvania, this research seeks to fill this gap.

Findings reveal three main categories of landowner coalitions and outlines a typical timeline of the process from inception to signing leases. According to respondents included in this research: while landowner coalitions generally received better lease terms, bonus payments, and royalty percentages on average than did individuals operating within the same context, and ultimately provided benefits to the greater community, this research identifies situations in which the landowner coalition model would not be beneficial. Variables of coalition success, both internal group characteristics and external contextual factors, are also identified. Focusing specifically on the effects of landowner coalitions on Pennsylvania’s farm operations, this research finds that participating in a landowner coalition helped farmers by enhancing an economic windfall used to maintain or reinvest in the farm, and procuring lease terms that were particularly advantageous for protecting farming operations. However, sometimes the additional income created unforeseen economic consequences and some land took a long time to be truly productive again after development. Research suggests that the landowner coalition model may prove promising for agriculturalists to utilize in application to other land use issues on the rural landscape, and continues to be used in negotiations of natural gas and wind energy leasing.

This project has three main objectives, listed below with a description of progress made towards each thus far.

- Assess the impact of Marcellus Shale development landowner coalitions on the long-term sustainability of farmers and farming communities in Pennsylvania using relevant background information and primary data from landowner coalitions, their advisors, and experts in the northeast and southwest regions of Pennsylvania.

-

Data collection and analysis are completed. Outreach and dissemination of this information is ongoing, including the publication of a fact sheet through Penn State Extension and a Webinar in August 2018 through Penn State Extension, which is widely utilized by the agricultural community. Results: This research set out to assess the impact of Marcellus Shale development landowner coalitions on the long-term sustainability of farmers and farming communities in Pennsylvania. In order to make this assessment, this research outlined the effects of signing a lease with a coalition on farmer members. From the initial offers from gas companies of two, five, or twenty-five dollars per acre to the thousands of dollars per acre that some landowner coalitions finally received, the income for farmers changed from a small boost, to a windfall earning of large proportions. For some farmers, this income protected them from having to sell part or the entirety of their farm, and was especially helpful for older farmers looking for a chance to retire. Key to the benefit of this income was the fact that it was a liquid asset, something farmers generally have little of.

Some respondents saw natural gas development, and specifically leasing through the coalition model, as a way to provide the economic, personal, and environmental protection necessary to support the agricultural landscape and preserve it for generations to come. A number of the lease terms attained by coalitions included protections for the land leased that were especially important for agriculturalists. One example is the reclamation of well pads or any other land disturbance. An additional benefit of landowner coalitions to farmers specifically was their ability to reinvest in their farming operations. Respondents described using lease money to purchase additional cattle for their herd, more efficient farming equipment, and newer used trucks. The income generated through gas leasing certainly had effects on the quality of life of some farmers, and the relationships formed through the cooperation and conversations typical of the coalition model were found to be particularly helpful to farmers, either through additional opportunities for support and collaboration between agriculturalists, or greater understanding from others. However, possible negatives for farmers included situations where a large windfall of income was expected and ended up spent before it was received. Additional income also had unintended financial effects in some cases, and some agricultural suppliers faced challenges as farming operations changed and some farmers retired. In addition, agricultural land took a long time to be truly productive again after development.

These results and conclusions continue to be disseminated widely. The publication of a fact sheet through Penn State Extension is underway, and I will complete a webinar in August 2018 on the topic through Penn State Extension's webinar series as well. These outlets are widely utilized by the agricultural community in Pennsylvania. This research has been presented at numerous conferences, and two journal publications are planned, one of these is near ready for submission.

-

- Evaluate the landowner coalition’s ability to serve as a model of collective action for farmers in the Northeastern United States to control land use decisions surrounding future issues on the rural landscape.

- Data collection and analysis completed. Outreach and dissemination of these findings is ongoing. Results: This research aimed to evaluate the landowner coalition’s ability to serve as a model of collective action for farmers in the Northeastern United States to control land use decisions surrounding future issues on the rural landscape. Data collected through interviews suggested agricultural strategies such as dairy marketing and group orders for feed, as well as equipment-sharing programs. In addition, respondents discussed additional energy-related land use issues, such as solar energy development and power line right-of-way negotiations. Many respondents also discussed the possibility of the landowner coalition model being applied to pipeline negotiations, although many different opinions were expressed in regard to whether such a model would work in that instance. While respondents mentioned a number of future applications and discussed how these may or may not work at length, wind energy development was the only case that has proven itself as an appropriate application for the model. Immediate effects of the use of coalitions for natural gas negotiations also exist. For example, some landowner coalitions held meetings to discuss how the group can be useful in the future. In addition, findings show that landowner coalitions created new networks and social connections between landowners that remain after the coalition disbanded.

- Identify evidence-based recommendations for best practices and procedures for future landowner coalitions to be distributed to farmers, their advisors, and experts throughout the state and presented at both academic and key stakeholder meetings.

- Data collection and analysis complete, with outreach and dissemination ongoing. Results: This research sought to identify recommendations for best practices and procedures for future landowner coalitions. To this end, findings have identified a number of variables of coalition success, although only a few are under the control of landowners. Beginning with group size, some respondents noted the benefit of larger groups, explaining that the greater the number of acres that a group brings to the table, the better that they could do in negotiations. On the other hand, however, other respondents noted some distinct advantages afforded by keeping the group small, such as ease of decision-making and homogeneity of beliefs and ideas. Location also seemed to effect the success of coalitions. This is true both because of the location of geological formations, and the spatial distribution of a company’s lease holdings. Market conditions are of course dependent on a combination of variables, such as location and timing, but also operated independently to provide conditions for varied degrees of success for coalitions. The success of a group also depended on the perspective of the company they decided to lease with, and more broadly on the perspective of the companies operating or leasing in that area. Some gas companies seemed amenable to or even excited by leasing landowner groups, while others were opposed to the idea and even hostile to their efforts. The last variable of coalition success mentioned by respondents was trust. This trust came from both existing relationships and the knowledge that everyone benefited collectively from the group’s actions. Although not always explicitly stated, respondents seemed to suggest that groups that were landowner-led were more successful because of the tendency for group members to trust group leadership. However, some respondents who had been part of entrepreneur-led groups also expressed trust in the leaders in most cases.

- These results and conclusions continue to be disseminated widely. The publication of a fact sheet through Penn State Extension is underway, and I will complete a webinar in August 2018 on the topic through Penn State Extension's webinar series as well. These outlets are widely utilized by the agricultural community in Pennsylvania. This research has been presented at numerous conferences, and two journal publications are planned, one of these is near ready for submission.

The rapid development of natural gas in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale formation prompted landowners to seek information to guide their leasing decisions to increase their profits, improve their household’s quality of life, and protect the natural resources on their land. Many farm and forest landowners turned to landowner coalitions for information sharing and collective action to counterbalance powerful industrial interests. In Pennsylvania alone, nearly forty landowner coalitions have formed to gain collective bargaining power in negotiations with industry representatives. Altogether, these landowner coalitions represent well over 500,000 acres and vary in size, scope, and structure.

Many Pennsylvania farmers, in particular, formed or joined landowner coalitions because of the scale and long-term impact of leasing decisions for their farms and livelihoods. For those who decided to lease, they faced a daunting challenge of maximizing farm income while minimizing production, environmental, and health risks. It was uncertain how shale gas development would affect quality of life for themselves and their communities, their ability to pass their farm on to the next generation, and marketing/production decisions. Could a farm that signed a lease for shale gas development continue to farm sustainably?

Little research has been done to evaluate the outcomes attained by coalitions in Pennsylvania or explore how they have affected shale gas development in the region. This research fills this gap by describing landowner coalitions and how they negotiated leases, and by assessing the impact of landowner coalitions on the long-term sustainability of farmers and farming communities. This research also runs counter to previous research on farmers in the Marcellus region that has suggested that they were powerless against industry interests and felt trapped in leasing negotiations. Instead, landowner coalitions are seen as a model of collective action farmers and other private landowners in the Northeastern United States have used, continue to use, and may use in future contexts to exert increased control over their own land use decisions.

With the changing energy landscape in the United States, rural areas will likely continue to see new waves of energy development (oil and gas, wind and solar) and other land use issues confronting private landowners, including agriculturalists (power lines, pipelines). The findings from this research suggest that farm and forest owners, through the coalition model, are able to gain more power in negotiations with industry and therefore procure more just outcomes for their energy resources. This research also identifies the coalition model as a model of collective action agriculturalists can use to control other types of future development of their property, ensuring that contracts are profitable, allowing them to continue as good stewards of the land, and helping to strengthen their community.

Cooperators

Research

The primary purpose of this study is to present a grounded theory of landowner coalitions that is based upon research guided by four main research questions: What are landowner coalitions? How/why did they come about and what process(es) did they go through? What results were they able to achieve? And what are the advantages and disadvantages of membership in a landowner coalition? In addition, a secondary objective is to evaluate evidence-based recommendations best practices and procedures for future landowner coalitions, the impact of Marcellus Shale development landowner coalitions on the long-term sustainability of farmers and farming communities in Pennsylvania, and the landowner coalition’s ability to serve as a model of collective action for farmers in the Northeastern United States to control land use decisions surrounding future issues on the rural landscape.

This research necessitated a qualitative research design due to the lack of previous research on the topic, and the nature of the research objectives and questions. First, qualitative research is particularly well suited to examine topics or phenomena that are “ill defined” or “not well understood” (Ritchie & Lewis 2003: 32). As very little research has been conducted on landowner coalitions (with the exceptions of Jacquet & Stedman 2011; Liss 2011), there is still a need to define the phenomena. As such, this study sought to both describe and define landowner coalitions. As Ritchie & Lewis suggest, the “open and generative nature of qualitative methods allow the exploration of such issues without advance prescription of their construction or meaning as a basis for further thinking about … theory development” (2003: 32). Because this research had both theoretical and applied components, this section will outline the specific qualitative approaches utilized for each research objective.

The first research objective, the theoretical component, was to describe and define landowner coalitions. Description of the phenomenon called for explanatory qualitative research (or exploratory in the case of Singleton & Straits 2005), which is concerned with “why phenomena occur and the forces and influences that drive their occurrence” (Ritche & Lewis 2003: 28). Such research seeks to describe the influences, motivations, origins, and contexts of social phenomena (Ritchie & Lewis 2008). In this particular case, research questions were: What are landowner coalitions? How/why did they come about and what process(es) did they go through? What results were they able to achieve? What are the advantages and disadvantages of membership in a landowner coalition? Through answering these questions, the research was able to move from description to definition. This called for generative research, which is concerned with “producing new ideas ….as a contribution to the development of social theory” (Ritchie & Lewis 2003: 30). Through generative qualitative research, new theory was developed in order to understand landowner coalitions as an emergent social phenomenon. Qualitative research was particularly well suited to describe and define landowner coalitions because of its’ ability to gather in-depth information capable of revealing what lies behind social phenomena, and its’ lack of predetermination which allows it to recognize and capture emergent concepts (Ritchie & Lewis 2003).

The applied component of this research included three remaining research objectives: (1) identify evidence-based recommendations for best practices and procedures for future landowner coalitions, (2) assess the impact of Marcellus Shale development landowner coalitions on the long-term sustainability of farmers and farming communities in Pennsylvania, and (3) evaluate the landowner coalition’s ability to serve as a model of collective action for farmers in the Northeastern United States to control land use decisions surrounding future issues on the rural landscape. These research objectives required the use of evaluative qualitative research, which is concerned with “how well” something works, and can identify factors of success of a model, as well as its’ organizational components and effects (Ritchie & Lewis 2003: 29). Qualitative research is well suited for evaluation because it focuses on actual rather than intended effects, and is responsive to a diverse set of stakeholder perspectives (Patton 2002). This applied component of the research sought to use the knowledge generated in the theoretical component to provide useful information to landowners. Ritchie & Lewis explain,

In order to carry out evaluation, information is needed about both processes and outcomes and qualitative research contributes to both. Because of its flexible methods of investigation, qualitative methods are particularly adept at looking at the dynamics of how things operate. They can also contribute to an understanding of outcomes by identifying the different types of effects or consequences that can arise from a policy and the different ways in which they are achieved or occur (2003: 29).

Although this research describes, defines, and evaluates a model or process rather than a policy, qualitative methods are employed due to these unique capabilities.

Because no conceptual framework or theory exists to wholly explain landowner coalitions, a grounded theory approach was used to construct such a theory from the data collected (Strauss & Corbin 1990; Charmaz 2006; Creswell 2007). The method garnered its name because it produces theories that are “grounded” in the data themselves. The inductive analysis of data rejects predetermination of findings and allows data to form the foundation of theory, as opposed to analyzing data through a particular theory “lens” (Charmaz 2006). More specifically, this research utilized Charmaz’s constructivist/interpretive grounded theory approach, which calls attention to differences in experiences and realities, as well as heterogeneity between people in levels of power, communication, and opportunity (2006). This method of qualitative research guided decisions throughout the research process, most notably in the data analysis stage. Grounded theory methods were applied to a case study approach to this research project. More specifically, this research represents a collective case study, as a single phenomenon (the landowner coalition) was illustrated through multiple cases within a regional boundary (Creswell 2007; Singleton & Straits 2005).

The data for this research was collected from Bradford, Susquehanna, Wyoming, Lackawanna and Wayne counties of Pennsylvania. Located in the northeast corner of the commonwealth, this study region was selected for three main reasons: the high volume of unconventional shale gas development, the presence of agricultural production, and the prevalence landowner coalitions. While the region as a whole represents all three of these categories, particular counties may not. This is because landowner coalitions do not conform to county boundaries, and therefore the study area has expanded into counties that may not meet one or more of the study region characteristics with the inclusion of large landowner groups that spill across county borders. In addition, Wayne County has been under a de facto moratorium since 2010, and therefore has had no unconventional natural gas development since leases were signed and test wells were drilled. Therefore, gas well numbers are low, even though many landowners in the county completed lease agreements as groups with natural gas companies.

Bradford, Susquehanna, and Wyoming are in the top 10 counties in the state in number of unconventional wells, with (1,416), (1,405) and (269) wells respectively (PA DEP 2017). Although Lackawanna (2 wells) and Wayne (5 wells) are ranked in the bottom third of Pennsylvania counties, they are included in this study because of the presence of landowner groups that signed leases with gas companies, although development never took place. Considerable amounts of acreage in all five counties is classified as agricultural land. Bradford County has the most farms and farm acreage, with 1,629 farms covering 308,000 acres, followed by Susquehanna County with 1,005 farms covering 166,000 acres. Wayne County’s 711 farms cover 113,000 acres, Wyoming County’s 508 farms cover 69,000 acres, and finally Lackawanna’s 303 farms cover 32,750 acres (2012 Census of Ag). Altogether, the region has over 4,000 farms covering more than 600,000 acres. Lastly, the best data available suggests that over 3,000 private landowners joined landowner coalitions in Susquehanna, Bradford, Wyoming, Lackawanna and Wayne counties, representing over 200,000 acres (Marcellus Drilling News, 2012).

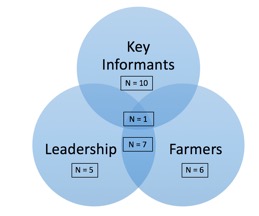

The research sample for this study included three categories of subjects: key informants, coalition leadership, and coalition farmers. Due to the informal structure and organization of most landowner coalitions, contact information for landowner coalitions is not readily accessible. Therefore, a combination of convenience and snowball sampling were utilized during this research (Weiss 1994, Singleton & Straits 2005). Key informants were contacted first. These included oil & gas attorneys, financial consultants, extension educators, law professors, and others. They were contacted via telephone or email using information publicly available online, or given to the researcher through snowball sampling. Next, leadership of landowner coalitions within the study area were contacted. Initial leadership were identified from a 2012 list of landowners groups published by Marcellus Drilling News. This list, although not 100% accurate or complete, listed the name and contact information of leadership for some groups. After successfully contacting a small number using the contact information on that list, snowball sampling was used to identify additional landowner coalitions and their leadership in the study area. Where possible, more than one leadership member from each group was included in the research sample to corroborate information.

Finally, the third category in the research sample was farmers who had participated in a landowner coalition. Some of these farmers were identified through snowball sampling from key informant and group leadership respondents. In addition, they were sought using announcements disseminated through Penn state extension offices in the region and local newspapers. Snowball sampling was also used within this category. In addition, farmers in landowner coalitions from previous studies within the study area were re-contacted to participate in this research. Care was taken to attempt to include both male and female farmers, small and large acreage farms, and a variety of different production types of farms within this sample subset. It’s important to note that these three categories were not mutually exclusive. Some key informants and farmers had served as leadership of coalitions, for example. Please see the attached visual of the research sample divided by group. Overall, twenty-nine interviews were conducted with twenty-nine respondents (one interview was conducted with two respondents, while one respondent was interviewed twice).

Before data collection began, an interview protocol was developed guided by the research questions and objectives. This semi-structured interview guide included a question at the end for the respondent to add anything additional, and allowed room for follow-up questions from the researcher. Prior to use, the interview protocol was evaluated by Rural Sociology faculty members at the Pennsylvania State University and revised accordingly. This interview protocol evolved as interviews moved from one category of respondents to the next, but remained grounded in a consistent set of questions based on the research questions and objectives. As Weiss points out, tailoring interviews to respondents or categories of respondents allows us to “gain coherence, depth, and density of the material each respondent provides” (1994: 3). Below is a list of topics covered in the interview protocol for each respondent group:

Key Informants:

- Why landowner coalitions happened, and what conditions allowed them to happen in the region

- Process of landowner coalitions from start to leasing (including recruitment and conflict)

- Markers and causes of success for groups

- Inclusion and exclusion of landowners

- Effects for farmers and their ability to farm

- Future applications of the model

Leadership:

- Why landowner coalitions happened, and what conditions allowed them to happen in the region

- Process of landowner coalitions from start to leasing (including recruitment and conflict)

- Goals of coalition and outcomes achieved

- Definition of success for landowner group

- Challenges faced

- Social connections within group

- Current state of coalition/future directions

Farmers:

- Inclusion and exclusion of landowners, recruitment

- Process for deciding on goals and choosing company

- Description of lease signing

- Effect on farm/farmer from signing with a group

- Comparison to what might have happened singing as an individual

- Definitions of sustainable farming and its relationship to leasing

After receiving approval from the Pennsylvania State University’s Institutional Review Board for the research project and all corresponding documents (consent form, interview protocol, etc), semi-structured interviews were conducted from November 2016 to August 2017. An effort was made to conduct all interviews in-person so that reactions, expressions, and body language could also be noted. Where necessary, phone interviews were conducted. Consent was obtained prior to all interviews. Whenever possible, respondents signed a consent form, either in person or emailed/faxed. However, in some cases verbal consent was obtained for phone interviews using the written consent form as the verbal consent guide. Of the twenty-nine interviews, one was conducted with two leaders present, while one key informant was interviewed twice. Interviews ranged from 16 to 102 minutes, with an average length of 48 minutes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim using a transcription service, and all personally identifiable information has been redacted from the transcript.

In addition to the twenty-nine interviews conducted from November 2016 to August 2017, seven interviews from a previous research project are also included in the data for analysis. The interviews were conducted from August to September of 2013 with leadership from one of the landowner coalitions included in the project, and centered on largely the same topic. These interviews are no longer attached to identities of individual research respondents. These interviews ranged from 53 to 98 minutes, with an average length of 77 minutes. Again, all interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, and all personally identifiable information has been redacted from the transcript.

The qualitative data generated through this research project (including the seven transcripts from 2013) were systematically coded according to grounded theory coding methods using qualitative data analysis software (NVivo citation). Although the research questions and objectives were used to steer the data collection, the data itself was allowed to steer the analysis, allowing for emergent themes (Charmaz 2002). First, attributes coding was conducted. This attached information such as date, fieldwork setting, participant characteristics, participant category, and landowner coalition name to each transcript. The first round of content coding was done using initial coding methods. Initial coding is done by coding all analytical ideas line by line in the transcript, taking care to remain open to all directions and emergent themes. The idea is for the analysis to come from the perspective of the respondents (Charmaz 2002, Saldana 2009). Next, the second round of coding was done using focused coding methods. Focused coding uses the most significant or frequent initial codes found in the first round of coding to synthesize and organize the data (Charmaz 2002, Saldana 2009).

Findings reveal three main categories or models of landowner coalitions: Model 1 was landowner-led, start to finish, Model 2 was landowner-led and then hired someone to market and/or negotiate, while Model 3 was entrepreneur-led, start to finish. The general timeline of coalitions began with landowners talking to their neighbors about offers to lease, sharing information and hosting meetings until a group comes together, deciding on goals, marketing the group to companies and/or negotiating with interested companies, and finally each individual signing their own group lease. Landowner coalitions generally received better lease terms, bonus payments, and royalty percentages on average than did individuals operating within the same context. However, for all of these outcomes, it is difficult to decipher the extent of the effect of landowner coalitions, since often their leases were offered to individuals after signing day.

Findings outline a number of potential benefits to landowners of joining landowner coalitions. According to respondents included in this research: members of landowner coalitions were able to procure a better deal due to their ability to attain greater negotiating power than did most individuals, largely thanks to offering large blocks of contiguous acreage and their increased knowledge and expertise. Coalitions also served as an equalizer, both between landowners and natural gas companies and amongst landowners. Respondents described helping their community as both a reason for starting or participating in a landowner coalition, and a goal of the coalition once it was formed. This help was administered through raising the standard for lease negotiations in a given area, making donations to the broader community from groups or individual members, and community development projects funded by industry requested by groups. Finally, coalitions provided a benefit to the fabric of communities by creating a space for new relationships to form. However, a number of negatives of landowner coalitions were also revealed: the focus on group needs versus those of a particular individual being paramount. In addition, there were groups of people that may have been left out of the coalition process for a number of reasons, and therefore not able to appreciate the benefits discussed above. These reasons include not owning property or mineral rights, or being in financial situations that didn’t allow them to wait for landowner coalition process to reach leasing.

This research also sought to identify recommendations for best practices and procedures for future landowner coalitions. To this end, findings have identified a number of variables of coalition success, although only a few are under the control of landowners. Beginning with group size, some respondents noted the benefit of larger groups, explaining that the greater the number of acres that a group brings to the table, the better that they could do in negotiations. On the other hand, however, other respondents noted some distinct advantages afforded by keeping the group small, such as ease of decision-making and homogeneity of beliefs and ideas. Location also seemed to effect the success of coalitions. This is true both because of the location of geological formations, and the spatial distribution of a company’s lease holdings. Market conditions are of course dependent on a combination of variables, such as location and timing, but also operated independently to provide conditions for varied degrees of success for coalitions. The success of a group also depended on the perspective of the company they decided to lease with, and more broadly on the perspective of the companies operating or leasing in that area. Some gas companies seemed amenable to or even excited by leasing landowner groups, while others were opposed to the idea and even hostile to their efforts. The last variable of coalition success mentioned by respondents was trust. This trust came from both existing relationships and the knowledge that everyone benefited collectively from the group’s actions. Although not always explicitly stated, respondents seemed to suggest that groups that were landowner-led were more successful because of the tendency for group members to trust group leadership. However, some respondents who had been part of entrepreneur-led groups also expressed trust in the leaders in most cases.

Next, this research set out to assess the impact of Marcellus Shale development landowner coalitions on the long-term sustainability of farmers and farming communities in Pennsylvania. In order to make this assessment, this research outlined the effects of signing a lease with a coalition on farmer members. From the initial offers from gas companies of two, five, or twenty-five dollars per acre to the thousands of dollars per acre that some landowner coalitions finally received, the income for farmers changed from a small boost, to a windfall earning of large proportions. For some farmers, this income protected them from having to sell part or the entirety of their farm, and was especially helpful for older farmers looking for a chance to retire. Key to the benefit of this income was the fact that it was a liquid asset, something farmers generally have little of.

Some respondents saw natural gas development, and specifically leasing through the coalition model, as a way to provide the economic, personal, and environmental protection necessary to support the agricultural landscape and preserve it for generations to come. A number of the lease terms attained by coalitions included protections for the land leased that were especially important for agriculturalists. One example is the reclamation of well pads or any other land disturbance. An additional benefit of landowner coalitions to farmers specifically was their ability to reinvest in their farming operations. Respondents described using lease money to purchase additional cattle for their herd, more efficient farming equipment, and newer used trucks. The income generated through gas leasing certainly had effects on the quality of life of some farmers, and the relationships formed through the cooperation and conversations typical of the coalition model were found to be particularly helpful to farmers, either through additional opportunities for support and collaboration between agriculturalists, or greater understanding from others. However, possible negatives for farmers included situations where a large windfall of income was expected and ended up spent before it was received. Additional income also had unintended financial effects in some cases, and some agricultural suppliers faced challenges as farming operations changed and some farmers retired. In addition, agricultural land took a long time to be truly productive again after development.

Finally, this research aimed to evaluate the landowner coalition’s ability to serve as a model of collective action for farmers in the Northeastern United States to control land use decisions surrounding future issues on the rural landscape. Data collected through interviews suggested agricultural strategies such as dairy marketing and group orders for feed, as well as equipment-sharing programs. In addition, respondents discussed additional energy-related land use issues, such as solar energy development and power line right-of-way negotiations. Many respondents also discussed the possibility of the landowner coalition model being applied to pipeline negotiations, although many different opinions were expressed in regard to whether such a model would work in that instance. While respondents mentioned a number of future applications and discussed how these may or may not work at length, wind energy development was the only case that has proven itself as an appropriate application for the model. Future research is needed to understand the conditions necessary for the coalition model to be a utilized.

Impacts

With the changing energy landscape in the United States, rural areas will likely continue to see new waves of energy development (oil and gas, wind and solar) and other land use issues confronting private landowners, including agriculturalists (power lines, pipelines). The findings from this research suggest that farm and forest owners, through the coalition model, are able to gain more power in negotiations with industry and therefore procure more just outcomes for their energy resources. This research also identifies the coalition model as a model of collective action agriculturalists can use to control other types of future development of their property, ensuring that contracts are profitable, allowing them to continue as good stewards of the land, and helping to strengthen their community.

This research has helped to outline the advantages and disadvantages of using the landowner coalition model, outlined variables of coalition success, and suggest future applications. These results have been disseminated through academic presentations (including the Rural Sociological Society, Penn State Energy Days, and Penn State's Shale Network Workshop), and are in the process of being disseminated through academic publications and Penn State Extension venues. The publication of a fact sheet through Penn State Extension is underway, and this research will also be disseminated through Penn State Extension's Webinar series in August 2018. In combination, these dissemination venues place the findings of this research study into the hands of extension professionals, rural landowners, and agriculturalists, as well as academics within the sustainable agriculture and energy impacts genre.

Accomplishments

Data collection and data analysis have been completed, and the dissemination of findings is underway. Twenty-nine semi-structured interviews were conducted from November 2016 to August 2017 with key informants, coalition leadership, and coalition farmers, identified through a combination of convenience and snowball sampling. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim using a transcription service, and all personally identifiable information has been redacted from the transcript. In addition to the twenty-nine interviews conducted for this project, seven interviews from a previous research project are also included in the data for analysis. The qualitative data generated through this research project (including the seven transcripts from 2013) were systematically coded according to grounded theory coding methods using qualitative data analysis software. Because no conceptual framework or theory exists to wholly explain landowner coalitions, a grounded theory approach was used to construct such a theory from the data collected. The findings have been published as a thesis with the Penn State Graduate School. The development of outreach materials and the dissemination of findings is ongoing.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

This research has been presented at four conferences so far: the Energy Impacts Symposium in Columbus, Ohio (July 26-27, 2017), the Rural Sociological Society Annual Meeting in Columbus, Ohio (July 27-30, 2017), Penn State's Shale Network Workshop in State College, Pennsylvania (May 17-18, 2018) and Penn State Energy Days in State College, Pennsylvania (May 30-31, 2018). Additionally, aspects of this research were included in a webinar in concert with Resources for the Future on September 6, 2017 (webinar), and will be featured in Penn State Extension's webinar series (https://extension.psu.edu/marcellus-shale-landowner-coalitions-form-function-and-impact). The publication of a fact sheet through Penn State Extension is also in process, which will be announced and linked to in a press release that will be sent to Penn State Extensions email list. Lastly, two journal articles are planned for publication from this research. The first, "Landowner Coalitions as a Tool for Procedural Energy Justice" is drafted and undergoing revision before sent for publication. The second will outline the landowner coalition model and contextualize it within natural resource management theory.

Project Outcomes

This research has one main limitation, and this is the difficulty in discerning the effects of landowner coalitions. Because there is good reason to believe that landowner coalition lease negotiations affected individual lease negotiations in an area, it is very difficult to consider what lease negotiations may have looked like without the presence of landowner groups. It is not enough to compare those who signed with a landowner coalition and those who signed as individuals, as the former most likely affected the latter. Unfortunately, looking to geographic areas that didn’t have landowner coalitions is inadequate because of the difference in contextual factors. If time had allowed, this study would have gained from comparison groups of farmers and non-farmers who signed gas leases as individuals. Future research is called for to use these comparisons to begin to sharply delineate the effects of landowner coalitions in the leasing landscape.

Additional opportunities for future research on the topic include expanding the study area. This should include other areas of Pennsylvania, as well as landowner coalitions in other shale plays. A particularly fruitful opportunity for future research is a case study is southwest Pennsylvania. Qualitative research would be well suited to explore why landowner coalitions did not appear in the southwest corner of the state, at least to the degree that they did in other production zones in the commonwealth. Opportunities exist for quantitative work as well. There is a need for future research to track lease terms and addendum across time in both coalition and individual leases. This will help to discern temporally if group leases have effected individual leases, as well as quantify some of the differences between group and individual leases, both in numbers and terms.

Future research should consider the conditions in the Marcellus Shale region of Pennsylvania that allowed landowner coalitions to proliferate in a way that they had not in other shale plays around the country. Data collected during the course of the current research project is well suited to begin to answer that question, and suggests that landowner coalitions were utilized at a much greater scale in the Marcellus than in other shale plays due to factors such as smaller parcel sizes, the frequency of current landowners owning their mineral rights, and a “blank” or undeveloped shale play. Further analysis is needed to fully answer the research question, and could help to judge whether the landowner coalition model can be successful in other contexts in other shale plays, and moreover when applied to wholly different scenarios. Additionally, emergent themes from the current study’s grounded theory coding method, such as “power”, “legal expertise”, “information sharing and communication”, and “talking to neighbors”, lend themselves to consideration as a tool for procedural energy justice, and future research should consider analyzing the landowner coalition model through an energy justice lens.