Final report for GNE18-190

Project Information

The purpose of this project was to identify the strategies used by female urban farmers and growers to develop and maintain their operations, and the extent to which these strategies also lead to positive community development, improved business networks, and enhanced local leadership. Pennsylvania State University graduate student Hannah Whitley used a participant survey and a number of qualitative research methods in this work, including semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and an innovative methodology called “photovoice.” As a community-based participatory action research approach, photovoice calls on participants to take ownership of data collection by documenting their lived experiences through photography and written or oral descriptions.

Research results, summarized in the Full Project Report and the Farmer and Grower Survey Report, provide information on participants’ motivations for farming, their strategies for success, and contributions that urban farms have on their communities. To complement the other research methodologies and share participant stories, the photovoice portion of this project manifested into a traveling and online photography gallery called “From Blight to Beauty” – The Female Farmer Photovoice Project. The project website documents participant’s experiences of community, collaboration, isolation, healing, and love, as well as the beauty of “growing foods and growing minds” in many of Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods.

A growing body of research calls for a focus on the intersectional issues which lie at the core of social justice in agricultural sustainability. In response, this research sought to embed urban agriculture within critical, feminist, anti-racist, intersectional frameworks that elevate marginalized voices to the forefront of social sustainability and encourages broader dialogues related to agricultural policy, landownership, capital acquisition, and institutional structural inequity. This study contributes to the literature on intersectional theory in its unique application to women farmers and gardeners in urban settings. In this process, growers show that although one’s gender remains consistently active in the matrix of one’s identities, it may not be the most relevant barrier in a given moment or context. Moreover, this study has identified several strategies that Pittsburgh’s urban farmers and gardeners use to develop and maintain their operations, ranging from resource access support networks like Grow Pittsburgh’s Garden Resource Center to land access facilitation such as the City of Pittsburgh’s Adopt-A-Lot/Farm-A-Lot program. Ultimately, Pittsburgh has implemented advanced urban agriculture policy and programs in comparison to other urban centers in the United States, which explains the city’s consistent ranking amongst areas with progressive UA ordinances. This said, there are several policy and practice changes that might be updated to create more equitable spaces for historically underserved farmers and gardeners.

Whitley identified several recommendations to support and promote urban agriculture. The seven major takeaways from this research, highlighted in the Full Project Report, are:

- There are intersecting issues throughout U.S. agricultural systems that affect urban women farmer’s land access, tenure, education, networking organizations, and opportunities for mentorship.

- Rather than growing solo, some women establish farms or gardens and create formal partnerships with local non-governmental organizations, elementary schools, and/or faith-based institutions.

- Educational programs and services offered by urban agriculture non-governmental organizations provide supportive spaces for women growers to build community and gain confidence.

- There are three key ways that urban agriculture has influenced Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods: (1) community development, (2) increased education and leadership; (3) grower empowerment.

- There are several constraints to sustainable production for historically marginalized urban farmers: Bureaucratic red tape; Community support; Operator finances; Inconsistent volunteers; Isolation; Lack of mentorship; Lack of (relevant) information; Land access and tenure; Marketing & communication.

- The following areas necessitate greater attention from researchers and extension educators: (1) Baseline information on policies, programs, services, & their effects on growers and communities; (2) best cover crops for raised beds; (3) location-specific & solution-oriented experiments; (4) low-cost & organic methods of soil restoration; and (5) marketing & distribution strategies for small-scale urban farms.

- Policy and practice updates are needed to create equitable spaces for historically underserved farmers. Advancements should include improved workshops & trainings, accessible timing & venues, reduced/free soil testing, standardized/online application systems, and increased advertisement for resource, finance, and leadership opportunities.

Objective 1: Identify the strategies that urban farmers and gardeners use to develop and maintain sustainable operations, and the extent to which these strategies also lead to positive community development, improved business networks, and enhanced local leadership.

Objective 2: Determine how urban farmers and gardeners work with nonprofit organizations, extension services, government programs, and fellow agriculturalists to create and sustain sustainable community-based food systems.

Objective 3: Develop evidence-based recommendations for practices and procedures that promote sustainable urban agriculture and improved agricultural productivity in the region, to be distributed to farmers, nonprofit organizations, extension personnel, academic researchers, and public policy officials.

Objective 4: Create a traveling photography gallery that will engage the broader community of agriculture producers and consumers by highlighting the challenges and opportunities for sustainable agriculture practice in urban areas, to be displayed at a minimum of three (3) agricultural education and networking events in the Northeast region.

Sustainability initiatives sponsored by many metropolitan cities have helped promote the growing urban agriculture movement across the U.S. Considerable academic scholarship has identified the benefits of sustainable agriculture and the challenges unique to its practice in urban contexts. These challenges include access to land and utilities (Ackerman et al. 2014; Kaufman and Bailkey 2010; Redwood 2009), lack of secure tenure (Lovell 2010); soil quality (Erickson et al. 2009; Porth and Hendrickson 2010), and vegetative destruction (Mougeot 2000). For agriculturalists who identify as racial, gender, and ethnic minorities, these challenges are often amplified and compounded by cultural, historical, and socio-economic barriers (Bowens 2015; Sachs et al. 2016). Nevertheless, little empirical evidence has revealed what tactics urban growers use to successfully navigate the obstacles they face. Even less scholarship has focused on challenges specific to urban farmers from historically marginalized communities and the strategies they have used to successfully navigate those challenges.

This project fills these gaps by identifying (1) the operational barriers unique to marginalized urban farmers, (2) the strategies that have been used to successfully navigate those barriers, and (3) recommendations for how support organizations can more effectively work with urban farms to increase their social, economic, and environmental sustainability. It contributes to our understanding of sustainability by identifying how farmers navigate the environmental and natural resource concerns unique to urban areas while calling attention to inequity in U.S. agri-food systems. Moreover, this project contributes to theoretical frameworks within the science of sustainability that seek to increase our understanding of how race, gender, and location intersect and inform local food systems. In this way, the project contributes to scholarship that seeks to improve the quality of life for urban farmers and their surrounding communities. Practical implications of this project’s findings will help farmers, non-governmental organizations, extension personnel, and policy-makers better frame and implement adaptation and mitigation strategies that support the environmental, financial, and social sustainability of urban farmers and gardeners. Findings encourage and promote best practices for the establishment and maintenance of local, sustainable food systems in urban areas of the Northeast region and beyond.

Cooperators

- (Educator)

- (Educator)

Research

Review of the Literature

May 2018 to January 2019 (not covered under NE SARE grant) - This project began with a thorough review of published literature in the field of urban agriculture. Emphasis was placed on identifying studies that have documented the experiences of and sustainability strategies employed by women and people of color who operate urban farms and gardens in the United States. This literature review shows that positive social, economic, and health impacts related to sustainable urban production promote local community development (Bradley and Galt 2013; Allen et al. 2008), improve food access and security (Armstrong 2000; Balmer et al. 2005; Corrigan 2011; Larsen and Gilliland 2009), promote cross-generational and cultural integration (Balmer et al. 2005; Beckie and Bogdan 2010), increase food and health literacy (Alaimo et al. 2008; Bregendahl and Flora 2007), provide market expansion for local farm operators (Feenstra 2007; Kremer and DeLiberty 2011), and promote awareness of environmental issues and ethics, sustainability, and local food systems (Bregendahl and Flora 2007; Kerton and Sinclair 2009; Travaline and Hunold 2010). Research on the challenges related to sustainable urban agriculture practice, however, have primarily emphasized the role of environmental and natural resource limitations, including: access to land and utilities (Ackerman et al. 2014; Kaufman and Bailkey 2010; Redwood 2009), lack of secure tenure and infrastructure (Lovell 2010); soil quality (Erickson et al. 2009; Porth and Hendrickson 2010), and vegetative destruction (Mougeot 2000). At the same time, literature on social sustainability has shown that deeper issues such as structural racism, gender inequity, and economic disparities disproportionately affect urban farmers and gardeners in historically marginalized communities (Bowens 2015; Reynolds and Cohen 2016; Rosan and Pearsall 2018; Sachs et al. 2016). The results of limited outreach and engagement is visible in studies whose results show that operations struggling the most to establish and maintain sustainable practices are those located in historically marginalized communities (Birky 2009; Cohen and Reynolds 2014). A growing body of research strives to recognize how race, gender, and ethnicity complicate barriers and opportunities for urban farmers, especially as contemporary scholarship calls for a focus on the intersectional issues which lie at the core of social justice in agriculture (Brown 2015; Sachs et al. 2016).

Following the completion of this project’s literature review, the graduate student (Whitley) submitted a thorough Institutional Review Board (IRB) application to the Pennsylvania State University IRB Office. Whitley wrote the project’s IRB protocol for human subject research which documents the project’s objectives, scientific background and gaps in current knowledge, study rationale, details the inclusion and exclusion criteria for potential project participants, outlines the project’s recruitment methods, documents the project’s consent process, details the project’s study design and procedures (described below), and includes a confidentiality, privacy, and data safety and management plan for information collected throughout the project. In addition to the IRB protocol, Whitley submitted the list of questions that would be asked during individual interviews with participants, the project’s photovoice reflection group discussion guide, a draft of the participant survey, and copies of the written consent and recruitment documents that were utilized during the interview, survey, and photovoice data collection process. All of this documentation was reviewed by a Penn State IRB officer and, after three revisions, was approved at the “Expedited” level. The study IRB was approved on September 27, 2018.

January to June 2019 - Primary data collection began in January 2019 (NE SARE funding for this project began on February 1, 2019). During this time, a qualitative research design, utilizing individual interviews, reflection groups, a photovoice methodology, and a participant survey was employed.

Project Methods

Research Objectives and Questions - This project necessitated a qualitative research design due to the lack of previous research on the topic, the nature of the research objectives and questions, and the need to facilitate conversations about sensitive topics such as race, class, and gender among research participants with diverse identities. Ritchie and Lewis (2003:32) describe how qualitative research is well-suited to examine topics or phenomena that are “ill-defined” or “not well understood.” While research on social sustainability and urban agriculture have shown that deeper issues such as structural racism, gender inequity, and economic disparities disproportionately affect urban farmers and gardeners in historically marginalized communities (Bowens 2015; Reynolds and Cohen 2016; Rosan and Pearsall 2018; Pennamin 2018; Sachs et al. 2016), the voices and experiences of people of color and women have been underrepresented within UA literature. Very little research has sought to identify how the rooted issues of gender inequity, structural racism, and economic stratification affect the operation of urban agriculture practices, and there is still a need to explore the phenomena and better understand what issues are being experienced at the individual level. Furthermore, while studies have shown that agriculturalists who identify as racial and gender minorities experience challenges amplified and compounded by cultural, historical, and socio-economic barriers, little empirical evidence has documented basic demographic statistics on the number of people who farm, garden, and/or grow food or raise livestock in the United States’ urban centers. Due to the nonexistence of data required to obtain a sample for a survey or provide secondary data analysis, qualitative sampling methods were necessary to identify respondents.

Research Approach - Informed by scholarship on critical urban agriculture, Whitley made a conscious decision to utilize qualitative methods that center the voices and experiences of participants and decentralize the position of the researcher as an “expert” on the study topic. Accordingly, the research methodologies used in this study seek to describe the challenges, strategies, and experiences of people and groups within an activity of interest, located within a specific time and place (Brown 2014).

Research Objectives and Questions - This research is framed by the following research questions:

- What are the motivations for historically marginalized urban growers to farm and garden in urban spaces?

- What challenges do historically marginalized urban growers experience while farming, gardening, and organizing around food activism?

- What are the strategies historically marginalized growers use to develop and maintain sustainable operations? What effects, if any, do these strategies have on agricultural operations and the broader community?

- How do historically marginalized urban farmers and gardeners work with non-profit organizations, extension services, government programs, and fellow agriculturalists to create and sustain their operations?

- How are historically marginalized urban farmers and gardeners’ experiences connected to broader structural inequities?

- How can institutions such as non-governmental organizations, extension, academic research, and federal programs better support historically marginalized urban farmers and growers?

In addition to the contributions of this project outlined in the Introduction, its methodology makes advances in research design. To collect data, this project utilized a unique qualitative research methodology called “photovoice” in combination with semi-structured interviews and participant observation. Photovoice is a tool that asks participants to use photography to represent and reflect on lived experiences and use their images to document needs, promote dialogue, and influence policymakers (Wang and Burris 1999). This methodology, further described in the sub-section “Photovoice Methodology,” is frequently used to facilitate conversation about sensitive topics such as race, class, and gender among research participants with diverse identities (Latz 2017). The utilization of a photovoice methodology was a particularly unique contribution from this study, as this project will simultaneously bridge the gap within the literature on sustainable urban agriculture, promote participant agency, and offer an empowering platform where participants use their narratives and photographs to share their experiences in public settings.

Moreover, the geographical context of data collection for this project is a bonus to scholarship on urban agriculture in the U.S. While Philadelphia has long been the focus of urban farm and garden research, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s second-largest urban center, has been ignored by sustainability scholars. In the last ten years, the City of Pittsburgh has developed community-based and neighborhood-food trust and food security programs, policy recommendation councils, and has created a coalition of urban farmers and gardeners who operate in the city. As of writing this summary (March 2020), there have been no scholarly publications that describe the experience of urban agriculturalists who operate in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This study is one of the first to explore urban agriculture operations in Western Pennsylvania’s largest urban center. The focus on Pittsburgh is innovative, timely, and emphasizes sustainable urban agricultural production and operators who have not been typically highlighted in academic scholarship.

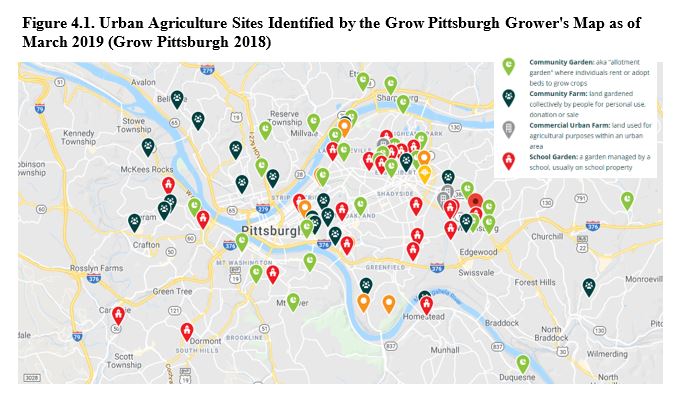

Study Location - The data from this research was collected in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. As of 2014, Pittsburgh’s metropolitan statistical area (MSA) boasted almost 8,000 farms, comprising over 908,000 acres of farmland (Rogus and Dimitri 2014:4). Pittsburgh’s commitment to sustainable urban agriculture and the improvement of community-based food systems is witnessed through policy and programming enacted by the Pittsburgh Foundation, Pittsburgh City Council, Grow Pittsburgh, and the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council. Additionally, with South Pittsburgh’s Hilltop Urban Farm having been recently named the largest sustainable urban agriculture operation in the United States (Zuidema 2018), Whitley hypothesizes that the city will soon become synonymous with urban agriculture excellence in the Northeast. Pittsburgh has been named among the top American cities leading the way with innovative and progressive urban agriculture ordinances (Haywood 2017; Lawson 2005). While there is no definitive list of urban agriculture operations or operators within the Pittsburgh MSA, the urban agriculture non-profit Grow Pittsburgh regularly updates a “Grower’s Map” on their organization’s website (visible in Figure 4.1.).

First launched in 2011, the user-generated map is compiled from information submitted directly by gardeners who self-categorize themselves as a “Community Garden,” “Community Farm,” “Commercial Urban Farm,” or “School Garden” (Grow Pittsburgh 2019). Currently, individuals who grow food in their “backyard, balcony, or inside [their] home” can opt to be added to the organization’s neighborhood count of backyard and personal gardens, though this information is not publicly available online.

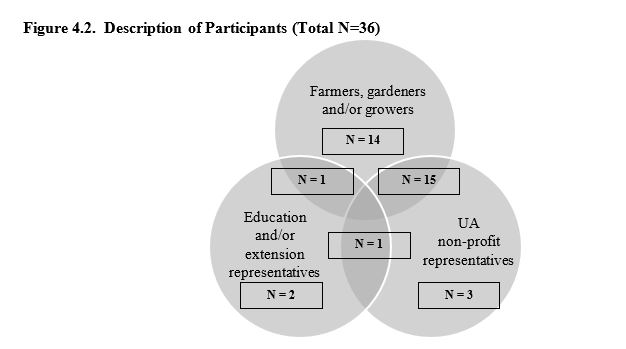

Research Sample - The research sample for this study included three categories of participants: education and/or extension experts, urban agriculture non-profit representatives, and Pittsburgh residents who identified as urban farmers, gardeners, and/or growers. Due to the overlapping nature of these positions, some research participants self-identified within more than one category.

For example, 15 participants included in this study’s sample were initially recruited because of their experience working in urban agriculture non-profit organizations, but they also identify as urban growers. To participate, subjects had to identify as having some connection to urban agriculture, be women between 18 and 85 years of age, and reside in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. To highlight the experiences of historically marginalized agriculturalists, this study looked specifically to recruit those who identify as women of color. In total, 36 women participated in this research, whether that be through an individual interview (N=30) or via participation in the photovoice project (N=18). Eleven respondents chose to participate in both an individual interview and in the photovoice project. Figure 4.2. provides a description of participants and their association with agriculture in Pittsburgh.

Participant Recruitment - This study and its recruitment process took place in two separate waves. The first wave began in January 2019 when Whitley began to recruit interview participants. Her pre-existing relationship with the founder of Pittsburgh’s Black Urban Growers and Farmers Cooperative helped build connections with this study’s initial participants. With this individual’s support for this project, she obtained access to several non-profit representatives and urban farmers, gardeners, and growers whom she would not have previously known. With the support of her gatekeeper, this study benefitted from a combination of convenience and snowball sampling that was utilized during this research (Singleton and Straits 2010). Whitley first contacted individuals whose names were provided by her gatekeeper. These included education and extension representatives, urban agriculture non-profit representatives, and women who identified as urban farmers, gardeners, and/or growers. These individuals were contacted via telephone or email using information publicly available online or provided through snowball sampling. In addition, participants were recruited in-person at the Pennsylvania Women’s Agricultural Network 2018 symposium held at Chatham University’s Eden Hall campus and from the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council’s Public Membership Directory, available online. Ultimately, this study’s sampling was sourced from a pool of individuals who were both convenient in their proximity and their (predicted) willingness to participate (Robinson 2014). A total of 30 interviews were conducted with 30 respondents during the first round of recruitment. These respondents represent 25 coalitions, universities, non-profit programs, representative councils, farms, gardens, and community organizations. The second wave of recruitment for this research, focusing on participants for the photovoice portion of this study, began in April 2019. Participants for the photovoice project were primarily recruited by snowball sampling through the individuals she had interviewed during the first wave of data collection. Every interviewee who identified as an urban farmer, gardener, and/or grower was personally invited to participate in this study’s photovoice project (n = 14). These individuals were invited to share a recruitment flyer with other female farmers, growers, and/or growers that they might have in their network. This second wave utilized pre-established relationships with study participants along with snowball sampling for the photovoice portion of this study. In total, 18 individuals participated in the photovoice portion of this study.

Data Collection - Data collected for this project took place through a short, online survey and three qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews, photovoice, and participant observation. Before data collection began, an interview protocol and a photovoice meeting discussion guide were developed, framed by this study’s research questions and objectives. The semi-structured interview guide and the photovoice discussion guide included a question at the end for the respondent to add anything additional and allowed room for follow-up questions from the researcher. After receiving approval from the Pennsylvania State University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the research project, photovoice exhibition, and all corresponding documents, the full data collection process took place from January 2019 to June 2019. Semi-structured interviews began in January 2019 and concluded in June 2019. Twenty-four (24) interviews were conducted in-person, ranging in location from non-profit offices to backyard gardens to favorite coffee shops and restaurants. To accommodate participants’ schedules or poor weather, 6 interviews were conducted via phone. Consent was obtained before all interviews. Whenever possible, respondents signed a consent form in-person. In some cases, however, verbal consent was obtained for phone interviews using the written consent form as the verbal consent guide. Interviews ranged from 9 minutes to 2 hours and 22 minutes, with an average length of 50 minutes. All interviews except two were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim using a transcription service. All personally identifiable information has been redacted from each transcript. Data collection for the photovoice portion of this study took place during the project’s reflection meeting in early June 2019. Before the reflection meeting, participants met in early May 2019 for an information session. During this orientation, participants became acquainted with the origin of this study, the purpose of this project and its methodology. This meeting took place in-person at a local community center and lasted 95 minutes. At the end of this orientation, all participants were provided a Lomography Simple Use film camera (loaded with one roll of color negative film) to complete the photography portion of the photovoice process. Next, participants were given three (3) weeks to take photographs that aligned with the theme decided by the group during the project orientation session – “Beauty from Blight.” At the end of the photography period, Whitley coordinated camera pick-up with all 18 of the photovoice participants and developed all photos in preparation for the photovoice reflection meeting. During the reflection meeting, participants selected 12 photos they wanted to include in the project’s photography gallery. For each of these photos, they were asked to write a 2-3 sentence narrative caption using a worksheet that described their photograph and its connection to the project’s chosen theme. The photovoice reflection meeting was modeled after unstructured discussion group methodologies, which set aside time for participants to build rapport, ask questions, and switch topics based on the flow of conversation (Nagle and Williams 2016). The meeting took place in-person at a local community center and lasted for 110 minutes. Written consent was obtained from all participants before the reflection meeting. Detailed notes were taken during the photovoice meeting and all personally identifiable information has been redacted. In addition to the formal data collection processes, participant observation took place at various community events, environment and agriculture workshops, community garden and UA non-profit volunteer opportunities, working group meetings, and urban agriculture networking events. During and after each event, Whitley took notes in her field journal and documented her observations, reflections, concerns, questions, musings, and moments of happiness as a participant researcher. She spent a total of 15 weeks in the field (primarily in the Homewood neighborhood of Pittsburgh) between January and June 2019. In the next three sub-sections, further detail on the design of the short survey, semi-structured interview and photovoice methods employed by this project is provided.

Semi-structured Interview Methodology - This project utilized a semi-structured interview instrument which consisted of 17 open-ended questions organized into five categories: introduction, food system work, perspectives on urban agriculture, perspectives on research themes, and closing. Follow-up and probing question examples are included on the same instrument, though not all such questions were asked of each participant. The five categories were arranged thematically to aid in interview structure and flow and were designed so that participants could take breaks, ask questions, or move to a different topic if they so choose. This interview instrument was shared with Whitley’s gatekeeper at the Black Urban Growers and Farmers of Pittsburgh Cooperative and was reviewed by this project’s advisor, Dr. Kathryn Brasier, to ensure its clarity and validity. The individual interview instrument allowed for follow-up and probing questions included and used if appropriate during the conversation. Even though participants were not provided with a copy of the interview instrument before meeting, several participants requested that they have a copy of the questions out in front of them during the interview, a request which Whitley happily obliged. As a result, a few transcripts contain audio where the interviewer was reading the interview instrument to make sure they did not have anything else to add for a category. At the end of each interview, participants were given a paper copy of Whitley’s contact information and a slip of paper with contact information for the project advisor and the Penn State Institutional Review Board. In some cases, participants requested a copy of the written consent form they signed at the beginning of the interview. In these cases, written consent forms were scanned and emailed directly to the participant through a PDF attachment.

Photovoice Methodology - The utilization of a photovoice methodology is a particularly unique contribution from this project, as it simultaneously bridged the large knowledge gap within the literature, promoted participant agency, and offered an empowering platform where participants use their own words and photographs to reveal their experiences in public settings. Based upon the theoretical literature on education for critical consciousness, feminist theory, and community-based approaches to documentary photography, this methodology is a tool that allows participants to identify local issues and problems, use photography to represent and reflect on lived experiences, and use their images to document needs, promote dialogue, and influence policymakers (Wang and Burris 1999:188). As a form of participatory action research (PAR), photovoice participants are invited to document aspects of their lives through photography and then provide written or oral accounts of the images they capture. First called “photo novella” by researchers Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris in the early 1990s, photovoice was initially incorporated as part of a four-part needs assessment that examined women’s health in rural China (Wang and Burris 1997). During the study, women participants were invited to document their realities with cameras, thus centering the participants as experts in their own lives and empowering women to share their stories behind their photographs. Wang and Burris (1999:188) outline three main goals of any photovoice study: (1) to enable people to record and reflect their community’s strengths and concerns; (2) to promote critical dialogue and knowledge regarding important issues through large and small group discussion on photographs collected; and (3) to reach policymakers. The photovoice process typically involves a series of workshops where participants learn the basics of photography and discuss issues related to their community. Next, participants go into their community to create and capture images documenting their lives. In subsequent session(s), participants select their best and/or favorite images, write captions, and participate in a facilitated discussion. Most photovoice projects end with a community exhibition, during which invited community leaders and policymakers have a critical dialogue with photovoice participants on the topic(s) of their exhibit. Along with theoretical roots in feminist scholarship, Wang and Burris describe how photovoice “takes Freire’s concept [of images as catalysts for dialogue during cultural circles] one step further so that the images of the community are made by the people themselves” (1997:370). In the process of participants identifying community issues, photovoice asks them to “critically consider contributing factors,” which will ultimately raise participant critical consciousness and create momentum for social change (Carlson, Engebretson, and Chamberlain 2006). This concept, in combination with participatory documentary photography approaches, assumes that “those within the group or culture being documented have more expertise and insight than outsiders” (Latz 2017:41), and in the process of taking photographs and creating narratives as part of a photovoice project, this form of participant action research makes space for the lived experiences and voices of society’s most marginalized groups. Photovoice has become one of the most frequently used PAR approaches among social scientists and “shows no signs of slowing down (Latz 2017:4). Latz describes how the participatory action component of photovoice research “contrasts sharply with the conventional model of pure research, in which participants… are treated as passive subjects” (2017:3), which adds the immense potential for generating new knowledge that diverges from dominant narratives. A method that is flexible in its protocol and innovative in its participant-centered approach to knowledge and learning, photovoice places cameras in the hands of participants, shifting the essential nature of the research itself (Latz 2017:21). As an accessible way to “turn the tables” of whose voice is heard in policy discussions and an innovative tool “for collaboration and disruption” (Mitchell 2011), photovoice is a medium through which visual and auditory perceptions are used to acknowledge the “humanness” around us (Collier and Collier 1986).

Farmer and Grower Survey - A short, online survey was distributed to all interview participants who identified as farmers or gardeners. Conducted via Google Forms, this method sought to understand: What information growers are most in need of? And, how should this information be distributed? A total of 23 women participated in the survey. The study findings provide evidence-based recommendations for practices and procedures that promote sustainable urban agriculture, improved agricultural productivity, and determine how NGOs, Extension, federal programs, and researchers can best support historically underserved farmers and growers. Respondents were asked to describe their history with farming and gardening, their education and information needs, and their event preferences.

Data Analysis - This project utilized the framework analysis method to examine all data. Twenty-eight interviews were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed using a transcription service. In addition to the interview transcripts, photovoice reflection meeting observations, notes from participant interviews, and 15 weeks of participant observation were included in the data analysis process along with the narrative captions written by participants during the photovoice discussion. All data were coded using Version 12 of the NVivo Qualitative Analysis Software. Whitley made a conscious decision to not analyze the photographs taken during the photovoice process. Rather than incorporating a visual analysis component into this project, Whitley believes it is important that the individuals who participated in this process have complete ownership of their photographs and their artistic interpretations. It is not her place as an academic researcher to interpret their photographs and their experiences for them. By analyzing the written photo captions participants provided themselves, however, Whitley centered the participant’s knowledge, experience, and interpretation in her analysis. As Latz describes, “it is not about the photograph itself. Rather, what matters is the context in which the photograph is situated” (2017:18). Ritchie and Spencer (1994) outline five stages for conducting a framework analysis: familiarization, identifying a framework, indexing, charting, and interpretation. During stage 1 (“familiarization”), researchers “get to know” the data to assess its overall “feel.” By reading interview and reflection meeting transcripts, reviewing field notes, and recording emerging issues in the data, researchers get a sense of what data they’re working with. Stage 2 (“identifying a framework”) asks the researcher to develop framework (coding) categories informed by a priori concerns as well as emergent issues that arose during the familiarization stage. During this stage, the researcher creates a matrix output of rows and columns (often called “thematic categories”) that organize the data. Rows represent cases (different participants or different interviews/focus groups) and columns represent different themes and/or concepts identified in the raw data (Barker 2016). In each cell, the researcher begins to summarize data and adds illustrative quotes from transcripts. Gale et al. (2013) describe how this presentation of data allows for themes to be interpreted across a data set while still being connected to the individual participant or focus group. This way, you can see similarities and differences between participants, groups, and within the themes that have been identified. Stage 3 (“indexing”) involves systematically applying the framework to each interview transcript and photo caption. As the researcher works through each transcript, they highlight a chunk of text they think applies to a certain category (or categories) from the framework; the highlighted text is then “dragged and dropped” into its corresponding category. During her coding process, Whitley coded for all themes while reading through individual transcripts and photo captions. Though this process was very time-intensive, it allowed her to focus on one single case at a time. Once indexing was complete for all captions, notes, and transcripts, Whitley began to chart the data into a more manageable format (stage 4). The end product from this stage was a spreadsheet where all interviews were summarized and organized by the framework categories. For each theme, illustrative quotes were included, which corresponded to individual interviews and photo captions. This stage was very helpful to prep for stage 5: interpretation. During this stage, the researcher is tasked with finding patterns in the framework and “articulating one’s own sense-making of the data in the light of one’s research questions” (Parkinson et al. 2015:27.). During this stage, Whitley read through the framework spreadsheet, took notes on broad findings, and began to develop a set of themes that applied to each research question.

Researcher Positionality, Reflexivity, and Location of Self - Reflexivity is a process of reflecting on how the investigator could be influencing a study at every step of the research process (Cohen and Crabtree 2006). While qualitative scholars attempt to be a neutral influence on their participants and study site, it is impossible to fully remove a scholar from the research process. Ultimately, who you are and what you have experienced influences your standpoint, your interpretations, your decisions, and how you conduct research (Altheide and Johnson 1994). With this in mind, the researcher must situate themselves within a project, understanding that reflexivity requires an investigator to examine their conceptual baggage and ultimate influence on the research relationship. Whitley is a white, cisgender, heterosexual middle-class woman who was raised as a nondenominational Christian in the United States. She is among the first generation of her nuclear family to pursue undergraduate and graduate school training and was born into a low income, English-speaking home with lower-working class, white, cis-het parents on a rural cattle ranch and tree farm in western Oregon. She was born with and continue to benefit from the systems of white supremacy and cisgender heteronormativity that are institutionalized within U.S. society. She also acknowledges that having never lived or worked in an urban space before fieldwork for this project, she identified as an "outsider" to her study location. Though she identifies as a woman along with all participants in the research, the privileges afforded to her via her own race, nation of origin, language, accent, ability, religion, and education status placed her in a position of power, especially when compared to the number of Black women, Indigenous women, and women of color who participated in the study. Most of this project participants self-identified as representing low-income, increasingly gentrified communities of color. Whitley’s positionality as a white woman justifiably marked her as an untrusted newcomer for many participants. In addition, her position as a student at Penn State and her relationship with the NE SARE program raised additional distrust from participants. Knowing this, she consciously approached this research in the tradition of feminist research methods and worked extremely hard to gain the trust of community gatekeepers, organization heads, and neighborhood elders. It was not a rare sight to find Whitley humanizing herself as a researcher by sharing pictures of her nephew, telling stories about her time in Future Farmers of America, or by confessing her ignorance of how the city’s bus or garbage/recycling system worked. By being personable, unguarded, and through her conscious effort to amplify the knowledge, experiences, and voices of this study’s participants, she decentered her position as an “expert” in the research process. Her intent is and was to learn from the women doing on-the-ground work in Pittsburgh's urban agriculture scene and use her position to share their thoughts, feelings, and suggestions for how urban agriculture can be better sustained in the U.S. As a white woman critically examining issues of gender, class, and race, she had to be careful in her interpretation of the data, making sure that she did not attempt to speak for research participants who are women of color. To be an ally and advocate, her research must reflect the voices of those who participated in the research.

Generalizability, Reliability, and Validity of Findings - Qualitative research findings are based on subjective, interpretive, and contextual data rooted in a specific location at a specific time (Altheide and Johnson 1994). The subjectivity of such scholarship requires that scholars take active measures to maintain reliability and validity of their study and its findings. Creswell (2013) describes numerous methods that scholars can employ to promote the validity of qualitative studies and ultimately suggests that researchers utilize at least two. Within this project, Whitley engaged in peer review and debriefing, member-checking, and clarified research bias with her “Researcher Positionality, Reflexivity, and Location of Self” statement. During the review portion of this project, her research advisor and graduate committee questioned the methods, meanings, and interpretations of her data analysis. During the data collection process, she used member-checking with participants to describe interview themes she had heard from others and asked if similar sentiments resonated with them or if they had differing concerns. Qualitative research cannot be generalized on a statistical basis, and as such, the value of such studies is in revealing the breadth and nature of the phenomena under investigation (Lewis et al. 2014). Though this project is limited in statistical generalizability, its findings contribute to theory by “providing evidence about underlying social processes and structures that form part of the context of, or explanation for, behaviors, beliefs, and experiences” (Lewis et al. 2014:351). Pittsburgh, PA, has regularly topped the list of U.S. cities who lead the way with progressive urban agriculture ordinances, and as such, it is an excellent choice for a single site case study examining U.S. agriculture sustainability. Unique to the city is its industrial history and resulting environmental damages, its abundance of pre-established green space, government officials’ enthusiasm to implement and improve green space and sustainable urban agriculture, and the number of established UA education events, apprenticeships, training opportunities, support programs and services. Though these unique aspects add to the limits of generalizability beyond Pittsburgh, this project’ findings contribute to theories of critical urban agriculture scholarship that extend beyond the city. These findings can be generalized to a class of cases in urban agriculture by showing the range of views, experiences, outcomes, and the factors and circumstances that shape and influence them. Lewis et al. (2014:351) reason that these elements of qualitative findings are what can be generalized to a parent population, allowing representational generalization to take place.

Before addressing the findings for each objective, this report will contextualize this research by sharing the study’s participant’s characteristics and their motivations for involvement in urban agriculture

Participant Characteristics

During individual interviews and the photovoice meetings, several questions were asked to gain the context of participants’ daily lives and their history of involvement with farming, gardening, and food advocacy in Pittsburgh. The responses for each participant are recorded in Table 1, which presents descriptive characteristics of the 36 women in this study. Participants reported a history of involvement in agriculture activities that ranged from very recent (less than one year) to more than 20 years. 14 women identify exclusively as farmers, gardeners, and/or growers, three are solely UA non-profit representatives, one is an education and/or extension representative, and the remaining 18 categorize themselves as having more than one association with urban agriculture. To highlight the experiences of historically marginalized agriculturalists, this study aimed to recruit individuals who identify as women, particularly women of color. 100% of this study’s 36 respondents are women, 17 of whom identify as Black or African American, two identify as Latina or having more than one race or ethnicity, and 17 identify as white. These women range in age from 20 to 74 years, with the median age being 34-44 years.

Motivations for Involvement in Urban Agriculture

To gain better insight into their motivations for involvement in urban agriculture, participants were prompted during individual interviews and photovoice meetings to describe why they began to participate in UA. A comparative crosstabulation of responses are documented in Table 2. Respondents described five motivations for their involvement with urban agriculture: community, education, healing, self-fulfillment, and suitability.

Community - Six participants indicated that some aspect of community building was integral to their involvement within Pittsburgh’s agriculture scene. Natasha, a UA non-profit representative and grower in Homewood, spoke about the importance of urban agriculture bringing people back “in touch” with the land and with their community. She described: "If you listen to the seniors here or the people who are older, all they talk about is memories that they have of when they used to have their own garden. They used to do food growing with their parents and their grandparents, and how they’re disconnected from that [now] and don’t do that anymore. There’s just so much we can do to tackle in a neighborhood like this and I want to be a part of that." Sentiments of community disconnection were echoed by respondents who noted that ongoing redevelopment efforts, particularly in the East Liberty, Homewood, and Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar neighborhoods, have inspired them to fight gentrification through agriculture and land use policy. Shanola, a community organizer, grower, and UA non-profit representative explained: "Decisions were being made for communities and we didn’t have no voice at the table. It’s all connected to land, you see? Agriculture and roots is one way to it… I’ve been a community organizer for a long time, my parents were community organizers, this to me is just serving my people." Other respondents were driven by a desire to empower residents and “fix” their neighborhood. Those who aim to use agriculture as a vessel for community infrastructure improvement spoke of a need to move their organizations and neighborhoods in a “positive direction,” an essential step that would require “group building and some sort of community aspect” (Nessa).

Education - Six respondents saw education as their motivation for participation in UA. These individuals described how participation in a university course or experiences abroad expanded their passion for agriculture and food accessibility. Karen shared how serving in the Peace Corps in Ghana motivated her interest in domestic urban agriculture efforts: "I realized that the same kind of agriculture problems [I saw overseas] were the same kind of problems happening domestically and for some reason people were talking about them in a different way. I was interested in that and interested in getting involved to learn and grow more of my experience in food security." Unlike respondents whose quest for knowledge was motivated by previous education or travel opportunities, one mother’s desire to teach her children long-term sustainability practices resulted in her forming several community gardens. Mariann explained: "Once I had my daughter, I felt like I needed to do something that was more useful for a long-term. I never gardened as a kid and I really wanted to teach my kids; I wanted them to learn from a very young age." The desire for obtaining agriculture education was common among most participants, though the individuals who identified it as their motivation for participating in UA tended to be younger (ages 18-24) and white.

Healing - Four respondents began growing food in Pittsburgh as a way to reconnect with the land or to find solace away from stressful work environments. These individuals spoke of the need for a therapeutic outlook in their lives and praised the “calming aspects of playing in the dirt” (Lonnie). One urban grower had recently transitioned to UA from a conventional farm in rural Alabama. She described how her move to Pittsburgh was inspired by the need to “get away from a really intense environment” and “farm by [herself] and grow stuff by [herself] and see what [she can do by herself]” (Harper). Others echoed the beauty and convenience of urban agriculture. Melanie reflected: "I thought, 'What a beautiful life to be able to walk the half-mile from my house and go farm all day and then walk home.' I needed a change in my work environment. So I started an urban farm."

Self-fulfillment - For five individuals, participation in urban agriculture was a means of self-fulfillment – an act of satisfying their own goals or dreams. Some participants spoke about how their interest in growing food stemmed from childhood. Mabel described her youth growing up in Homewood: "My interest in gardening has been since I was a young girl. I used to look forward to the trucks coming up from one of the Carolinas, probably South Carolina, but all the watermelons, all the different melons, and it tastes so good. That was our introduction to farm-to-table: you get the food, then you eat it. It definitely had you aware that there were people out there growing lots of vegetables and fruits and then bringing them to your community… I wanted to do it too, and I was always pretty much in-tuned with mother nature." Self-fulfillment sometimes took on an inspirational or spiritual feeling of accomplishment. Ray, a community organizer, grower, and UA non-profit representative explained: "I’ve just always been excited at the idea of gardening and seeing it growing, getting a harvest… I’m just happy to grow something. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s so fulfilling to just go through the process and to nurture it and then consume it and you just… The whole cycle is very rewarding." Unlike the respondents whose self-fulfillment was internally motivated, other participants were inspired to create a better future for their families. Describing herself as a “reluctant gardener,” Jacki explained how her motivation for growing food is to create more healthy options for her grandson: "My neighbor, I could see that she had this – to me, it was just like a box, and I saw vegetables and things in it… She gave me a little flyer that she had in her house… Then I looked at it and that’s when I discovered that it was gardening vegetables and stuff. I was like, 'Okay, I don’t like dirt really. I don’t like bugs and worms.' My boyfriend was like, 'What can it hurt? It’s just a box. Just see what it’s about, just put it in your yard. If you don’t like it, you can just take it out.' Then I thought about my grandson… at the time, I think he was about three. I was like, 'Okay, I’ll give it a try for him.' For some, participation in urban agriculture was the culmination of life-long goals, spiritual fulfillment, or planting the seeds of health for future generations. Regardless, UA remains a way for some growers to bring about feelings of happiness, satisfaction, and love.

Suitability - The final reason respondents identified as motivating their participation is suitability – the degree to which UA is appropriate or fitting for their individual needs or desires. Within this theme, individuals mostly described how occupations in urban agriculture, particularly within the non-profit sector, combined personal and professional interests. The majority of these individuals began careers in one field and later transitioned to work in urban agriculture. These respondents motivated by suitability found positions within the education, extension, or non-profit sectors that combine their love of service with interests in food, agriculture, sustainability, and “playing in the dirt” (Lonnie).

Results for Objectives 1 and 2

Objective 1: Identify the strategies that urban farmers and gardeners use to develop and maintain sustainable operations, and the extent to which these strategies also lead to positive community development, improved business networks, and enhanced local leadership.

Objective 2: Determine how urban farmers and gardeners work with nonprofit organizations, extension services, government programs, and fellow agriculturalists to create and sustain sustainable community-based food systems.

Experiences with Urban Agriculture Support Programs and Organizations

This project found that the strategies that urban agriculturalists use to develop and maintain sustainable operations are primarily by working with non-governmental organizations, Extension, federal programs, and faith-based networks. As a result, the findings for objectives 1 and 2 are closely related and best reported in one section. Respondents identified multiple support programs, organizations, and partners that have supported them in their work as urban agriculturalists. These entities will be explored in three groups: formal partners, educational programming, and land and environmental resources.

Formal Partners – To sustain their growing operation, many respondents create formal partnerships with local, state, and nationwide non-profits, elementary/secondary schools, universities, and faith-based institutions. These partners exist as sources of land, labor, built, and financial capital that help sustain UA operations. Community gardeners, in particular, may choose to partner with elementary/secondary schools or faith-based institutions with the sole purpose of acquiring volunteers. Fay, a UA non-profit organizer, explained: “We have ties to a lot of faith-based organizations. It’s a win-win for them because it’s an outreach effort that they use to get congregants and parishioners involved through church.” Júlia, a UA non-profit organizer and farmer, described how her organization partners with over 30 schools, mostly public, and offer in-school education workshops to youth, and Nessa, a fellow UA non-profit representative, noted that formal partnerships with youth organizations have been excellent recruitment spaces to attract young farmers and gardeners. Respondents also explained how formal partnerships allow community gardens to benefit from improved financial capital, such as enhanced grant eligibility and fundraising opportunities. In their photostories, Taylor and Mariann described partnerships they have created with local education institutions, as shown in Figures 5.4. and Figure 5.5.

Educational Programming – In addition to the organizations and institutions that provide formal partnerships, respondents identified several supportive non-profits and community coalitions that seek to improve agricultural knowledge in Pittsburgh. The Black Urban Growers and Farmers of Pittsburgh Cooperative (BUGs-FPC), Grow Pittsburgh, Homegrown, the Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture (PASA), and the Pennsylvania Women’s Agricultural Network (PA-WAgN) were consistently named the top sources of UA education. In addition to formal organizations and coalitions, participants also identified social media platforms as being a key source of information. Jackie, a beginning farmer, described how her use of Instagram has contributed to the sustainability of her farm: “What I've done is I ended up creating an Instagram account… I've been slowly gaining more followers, which allows me now when I have an issue, I've put it on one of my posts and add a bunch of hashtags. Last week I put one on because I was having an issue with cucumber seeds. The people online were like ‘sprinkle the seeds and water it.’ What they said to do worked!”

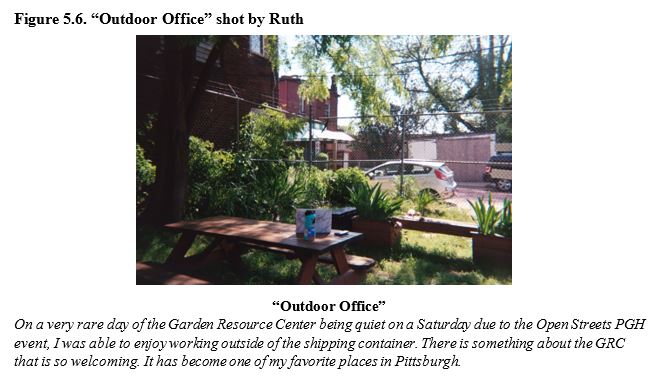

Land and Environmental Resources – Participants praised the Allegheny County Conservation District’s (ACCD) soil testing service, the Hilltop Urban Farm’s farmer incubation program, Grow Pittsburgh’s Garden Resource Center, and the Nine Mile Run Watershed Association as being key suppliers of land and environmental resources. The ACCD offers free soil testing and site analysis for community gardens, non-profit farms, and green space projects within the Pittsburgh MSA. In 2018, over $120,000 worth of free heavy metal and nutrition soil tests were conducted, providing soil testing for more than 300 people and 30 distinct community projects across the city (National Association of Conservation Districts 2018). For a fee, Hilltop Urban Farm’s Farmer Incubation Program provides new and beginning growers with access to rehabilitated urban farming acres, storage, solar electric, hoop houses, mobile coolers, and a shared tool library. Grow Pittsburgh’s Garden Resource Center, a tool-lending library and materials depot, stocks a wide array of gardening tools and materials including tillers, weed whackers, wheelbarrows, compost, and other farm and gardening supplies. Ruth captured the Garden Resource Center in one of her photostories (Figure 5.6.). Furthermore, the Nine Mile Run Watershed Association provided some urban growers with free or reduced-cost water tests.

Views on UA’s Influence on Local Neighborhoods and Communities

Participants described three ways that UA has influenced their neighborhoods and local communities: through community development, education, and grower empowerment.

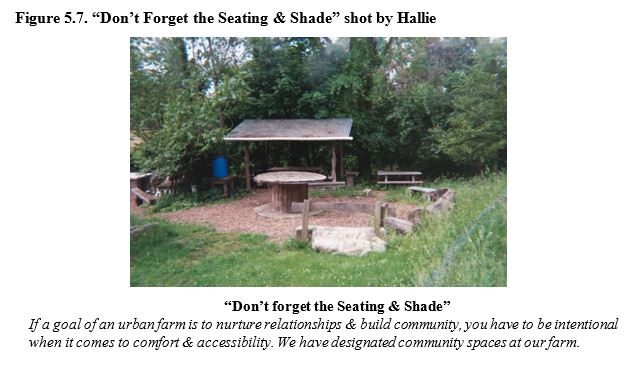

Community Development – “There’s power in playing in the dirt,” Lonnie, a UA non-profit representative and farmer explained; “It’s more than just people under the impressions of ‘Oh, it’s just growing a garden.’ You’re growing people…It’s what you don’t see growing – what’s inside people – that matters.” This sentiment was echoed by many respondents who explained that urban agriculture has and does play a key role in the development and improvement of economic, social, environmental, and cultural wellbeing in their communities. Many participants saw the community aspect of urban farming as being the largest benefit of production, with “growing foods and growing minds” often ranked in importance above “growing pocketbooks.” One of Hallie’s photostories (Figure 5.7.) demonstrates how important community is to her urban farm.

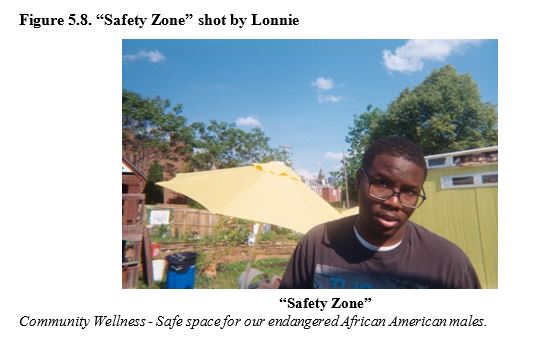

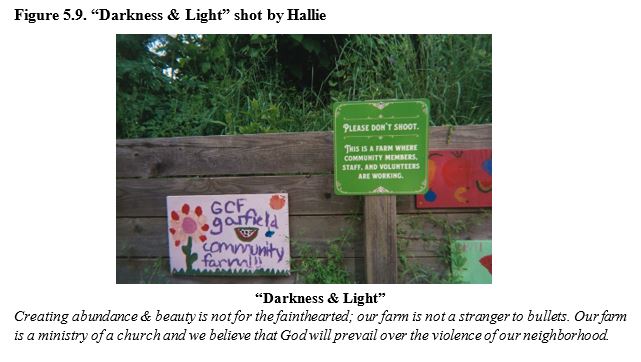

For some, community improvements have come about as the result of farms or gardens being established on the sites of violence and/or drug use. Lonnie and Hallie, UA non-profit representatives and farmers, described how their farms seek to provide a safe space for the community in their photostories (Figures 5.8. and 5.9.).

For some, community improvements have come about as the result of farms or gardens being established on the sites of violence and/or drug use. Lonnie and Hallie, UA non-profit representatives and farmers, described how their farms seek to provide a safe space for the community in their photostories (Figures 5.8. and 5.9.).

Along with providing a safe space for the neighborhood, some UA operations afford the community with programs and services in addition to their growing activities. It is common for UA non-profits to spearhead job training programs, financial literacy workshops, self-help classes, and even offer food pantry or healthful living education services in addition to agriculture-related activities. Many participants see urban agriculture as bringing about a sense of connectedness and community, as “It bridges gaps. It bridges age. It’s crossing diversity bridges. It’s bridging socio-economics too. You can connect with so many people on it. That’s powerful” (Inez).

Education – Education was consistently viewed as a vital aspect of urban agriculture operations. Many UA non-profit representatives described ways that UA is connected to youth health and nutrition. In the process of teaching children where their food comes from and what it looks like, urban agriculture programs make healthy food a realistic expectation. Ray, a UA non-profit representative, explained the “magic” that happens within UA programming: “Every workshop, every lesson in the classroom… There’s normally at least one person who feels they are not capable; they won’t do it right; this is just not going to turn out. And over time, when they see the seeds turn into sprouts or whenever we finish a workshop … They’re so impressed with the instant gratification of just completing it, and it makes them feel so good to have something to look forward to. It makes healthy food more fun and accessible.” Other growers described how they use their operations to create dialogue around agriculture and the broader ecosystem. Taylor, a local grower, explained how she uses her apiary to connect local concerns with global issues: “What I’m trying to do with honey is to create more of a dialogue around the true costs involved with nature. One thing I do is I often bring back the bees’ perspective, what’s currently happening, so I can tell their story on a regular basis just by what I’m observing and what I’m having issues with that. People instantly relate to them in a way that’s more internalized, and on their own, they get a deeper understanding of ‘nature is not separate from us.’” Integrating urban farms and gardens into the social landscape of cities, many operations strive to not only provide fresh and affordable produce to their communities but provide intangible programs and services in the process. Youth and consumer education, workforce development, and environmental education are all transferrable skills that may benefit those associated with urban agriculture in Pittsburgh. Ruth captured her views on the importance of gardening and education in one of her photostories (Figure 5.10.).

Grower Empowerment – UA operations and programs also provide space for growers to build community and gain confidence in their roles as farmers, gardeners, and food activists/advocates. Some participants described how their race and ethnicity have helped change the idea of what a farmer looks like, which has helped legitimize their own identities as growers and improved the confidence of youth of color. Inez, a UA non-profit representative and grower, described one such example: “I think for me actually being a person of color, and going into a classroom, and the kids, they're like, "Farmer Inez? Well, you don't look like a farmer." I was like, "What do you mean?" They're like, "Well, you're Black." I'm like, "There's a lot of Black farmers." And they're like, "But you're a girl." I'm like, "Yeah, there are girl farmers too." They're like, "Really?" "But do you have a farm?" I'm like, "I grow at schools. I grow at home. Do I have a farm? No, but it's challenging this idea, but I'm doing what farmers do." I think being able to redefine that as an overall or when they can see my Black face in that space.” The presence of farmers of color in education spaces, especially women farmers of color, challenges the idea of who a farmer can be and what growing food can look like. Many respondents of color explained how their work in urban agriculture helped them reconnect to the land and their ancestors – “Reconnecting and realizing that after being brought to this country against their will and after people who have come here trying to have more opportunities, that there’s still roots in the ground” (Júlia). Some growers described how starting agriculture operations empowered them because they accomplished something they never thought they could, whether that be growing a cucumber from seed to stock or building a gardening table by themselves. Ray captured a photostory demonstrating this sentiment in Figure 5.11.

Many participants also spoke of how there is “power in knowledge,” and in the process of learning how to grow food in the city, they have grown in “mind, body, and spirit” (Jackie). A few were empowered by how growing their own food no longer left them reliant on an institutional system. Knowing what went into a crop, having nurtured it from start to finish, was a powerful feeling for many growers.

Results for Objective 3

Objective 3: Develop evidence-based recommendations for practices and procedures that promote sustainable urban agriculture and improved agricultural productivity in the region, to be distributed to farmers, nonprofit organizations, extension personnel, academic researchers, and public policy officials.

During individual interviews and photovoice meetings, participants were asked to describe what challenges they have experienced while farming, gardening, or organizing around food activism in Pittsburgh. A comparative crosstabulation of responses is documented in Table 3. Results indicate that constraints on sustainable urban agriculture operations in Pittsburgh are various. Participants identified the following to be major determinant factors of their operations: bureaucratic red tape, communication, community support, finances, inconsistent volunteers, isolation, lack of mentorship, lack of (relevant) information, and land access and/or tenure.

Bureaucratic Red Tape - Many respondents explained that legal access to vacant or abandoned land can be an extremely complex process to navigate, which often left them feeling frustrated, isolated, or led astray by government and policy officials. These parcels represent a powerful opportunity for urban farming and gardening activities, and while programs such as the city-sponsored Adopt-A-Lot/Farm-A-Lot processes promote land accessibility for new and beginning growers, lack of information and support staff remains a key inhibitor to land accessibility. Founded in 2013 as part of the city’s Vacant Lot Toolkit, Pittsburgh’s Adopt-A-Lot program was “created to allow residents a streamlined process by which to access city-owned vacant lots for food, flower, or rain gardens” (City of Pittsburgh 2018). After identifying more than 27,000 “distressed” vacant lots among 145,000 vacant parcels within the city limits (Pittsburgh City Planning 2015), Pittsburgh’s Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) categorized 6,000 of these lots as “push to green.” Under the “push to green” designation, these 6,000 lots were set aside for redevelopment designated as greenways, parklets, community gardens, or urban farms. From 2013 to 2015, 114 vacant lots were transformed around the city (City of Pittsburgh 2018). Drafted with assistance from the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council, the Urban Redevelopment Authority approved policy updates to the city’s Adopt-A-Lot program in July 2018. Incorporating a pilot “Farm-A-Lot” program, this update made changes to the policy’s short-term lease and liability insurance requirements. Under the 2013 policy, the Adopt-A-Lot program offered 1-year leases, renewable for up to three years. Acknowledging that the previous policy’s short-term nature discouraged potential farmers and offered little security for long-term projects or initiatives (Tolliver 2018), the 2015 URA Board approved land lease policy allowing for longer-term leases and lease-to-own purchase agreements on a case-by-case basis. The city’s Adopt-A-Lot/Farm-A-Lot program presents a great opportunity for growers to acquire land at low-cost, however, for many participants, experiences with the program were plagued by confusion and miscommunication. Talia, a vegetable grower, explained: "There are a couple of ways [to access land], but I found that the processes are confusing and there’s nowhere to find information. Even I was looking at the Adopt-A-Lot website. It was like you have to do three different forms, and in those three different forms, you have ten different steps. You have to go to the office four different times. And there’s like not a phone number." In addition to the unclear application process, many respondents described the Adopt-A-Lot application process as being incredibly costly and time-consuming. Stella, a beginning grower, described how she had spent more than $500 on soil testing and remediation for two Adopt-A-Lot parcels. Ultimately, her applications were denied and she “wasn’t given a reason why” despite multiple attempts to contact program officials. The theme of confusion was shared by multiple growers who attempted to navigate through the bureaucratic maze of urban land and utility access. For many, frustration grew out of a general lack of information. Jaqueline, a grower on Pittsburgh’s North Side, explained: "I bought a house recently, but before doing so, I was in communication with the city about vacant lots and maybe purchasing lots to have an actual urban farming operation. It felt very red tape-y and there was still a lot of bureaucracy to try and work through… I found that to be frustrating because there’s plenty of vacant lots. In my opinion, they’re just holding onto them for future development. I get that, but I also am pissed off about that… Mostly, they would defer and be like 'That’s for another department. We don’t deal with that'… and then it’s just like this run around with no clear like no direct person to go to. I feel like there should be a more streamlined way to make those pieces of land available to people who are going to do something with them." Complex administrative systems and unclear zoning laws are two of the main challenges respondents named, and while they are considered to be “steps in the right direction” (Melanie), excess fees, paperwork, and government navigation “can really dampen the spirits of someone who is feeling enthusiastic about growing food” in a city (Stella). The City of Pittsburgh requires that any free-standing structure have a Certificate of Occupancy permit acquired through the Office of City Planning’s Zoning Division (Grow Pittsburgh 2017). At this time, high tunnels and greenhouses, common structures in urban farms and gardens, are considered property structures, thus necessitating Zoning Division approval before construction (Grow Pittsburgh 2017). The placement of any “structure” on a lot necessitates compliance with setback and height requirements, which vary based on the zoning district (Pittsburgh City Planning 2015). If proposed plans do not meet the city’s zoning requirements, however, exceptions can be made. Applicants can begin a “variance process” in which the Zoning Board of Adjustments meets to hear appeals to consider granting variances or other special exceptions to the zoning ordinance (Pittsburgh City Planning 2015). Participants also described confusion regarding the city’s policies on livestock residence within residential areas. Within Pittsburgh’s city limits, farm animals can be integrated into farm operations depending on local zoning law and space available. In 2009, the city’s urban agriculture zoning ordinance, allowing only three chickens or ducks on a 2,000 square foot lot, charged residents fees totaling $340 and required a hearing process that took 10-12 weeks for administrative processing (Born 2015). Since Pittsburgh’s City Council approved new zoning laws in 2015, however, operators can now “bring a site plan detailing a desired coop, apiary, or other animal structure and get a permit in a single day for $70” (Born 2015). The improved livestock policy has been hailed by Pittsburgh’s farmers as being a “big step forward” for inclusive and sustainable urban agriculture policy (Born 2015). One article described the new livestock policy as being “one of the more progressive [urban agriculture] codes in the country” (Gravina 2015). Under the 2015 zoning ordinance, Pittsburgh residents living on properties of at least 2,000 square feet could purchase a permit allowing five chickens or ducks or two dehorned miniature goats, as well as two beehives (Born 2015). For each additional 1,000 square feet, residents are permitted one additional chicken or duck. No additional large livestock (goats) are permitted for lots under 10,000 square feet (Grow Pittsburgh 2018). Though current policy allows for farms to contain bees, chickens, ducks, and goats, there remain several regulations related to space requirements, animal structure size and positioning, excrement and odor maintenance, and animal sex/appearance requirements that may continue to limit an operation’s possession of livestock within city limits. Animal structure size and positioning, for example, is a particular concern for farms made up of several lots. As described in the previous paragraph, many of Pittsburgh’s urban farms and gardens are comprised of multiple lots. If an animal structure were to cross a lot’s property line, operators would be forced to seek city approval, thus accumulating a heavier financial burden and an increase in time spent waiting for administrative processing. In addition, the limited number of animals permitted within city limits is a severe limitation for farms and gardens receiving revenue from animal-related byproducts such as egg sales, goat’s milk, and value-added products such as soaps and lotions. To secure financial sustainability, Pittsburgh’s urban farms and gardens might be required to diversify their operation. For agricultural operations possessing a limited budget, the reality of financial sustainability may be constrained by zoning regulations, livestock legislation, space requirements, and administrative back-logging. When it comes to zoning legislation, one of the biggest setbacks for Pittsburgh’s urban farmers and community gardeners is that, according to current city policy, structures cannot be built spanning multiple properties (Pittsburgh City Planning 2015). Many of Pittsburgh’s urban farms and gardens comprise multiple lots, a facet possessed by many operations participating in the Adopt-A-Lot/Farm-A-Lot program (Grow Pittsburgh 2018). As a result, if a high tunnel or greenhouse were to cross a current property boundary, the lots must be consolidated by the city’s Planning Board, which would result in increased processing time and higher processing fees (Pittsburgh City Planning 2015). For city farms and gardens boasting high acreage, this policy might pose a significant administrative and financial barrier.

Communication - In addition to the challenges associated with navigating local government structures, respondents found communication and information accessibility, or lack thereof, to be an inhibition to the sustainability of their operations. New and beginning growers spoke of the difficulty they had getting in contact with established growing operations and urban agriculture non-profits, especially as “there are a lot of non-profits and [they] do so many similar things, so it’s always trying to figure out who’s doing what” (Kenzie). Frequently, growers expressed concern for the “lack of communication within urban agriculture and with agriculture in general” (Talia), which makes it difficult for growers to identify what services are available, what organizations offer, and what events are being organized. In addition, participants spoke of their hope for a “central place that tells you how to begin – how to start an urban garden or farm” (Eve) and were irritated by how difficult it is to access email listservs and organization newsletters. Harper, a beginning grower, expressed her frustration: "I feel like now that I’ve been here for a decent amount of time, now I’m on a bunch of email lists, and I see that stuff [funding, opportunities, education programs], it took me so long to get to that place. It shouldn’t be that hard."

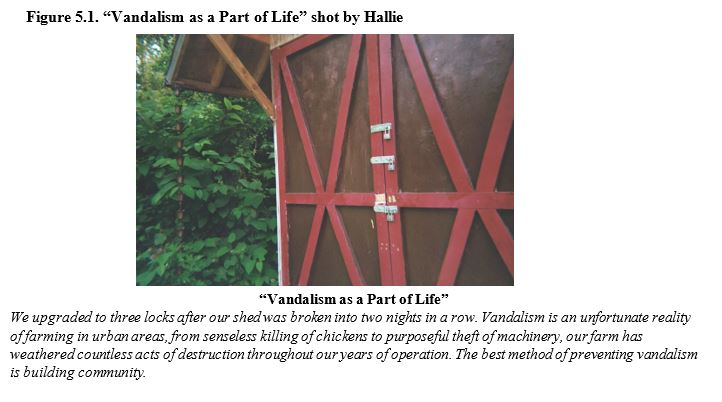

Community Support - For the growers who chose to establish farms or gardens on vacant lots in their neighborhoods, community support, or lack thereof, remains a large challenge to their operation’s success. Inez, a UA non-profit representative and gardener, explained how community buy-in is essential for the longevity of neighborhood gardens, noting: “People’s time seems to be a huge, huge thing,” and without local support, the success of such an operation may be limited. Hallie, a white UA non-profit representative and grower, explained how fear of gentrification is a constant contemplation while growing in a historically Black community:

We need to connect with people where they are, and that’s a struggle. We don’t want to be bringers of gentrification, we want to make sure it [the farm] is a resource. We need to figure out what the community wants and make sure there’s no misunderstanding.