Final report for GNE19-193

Project Information

Agrihoods are a recent trend in real estate development that integrate agricultural amenities - such as working farms, orchards, or community gardens - into residential or mixed-use communities. As an emergent trend, agrihoods have the potential to enhance farmland preservation and local and regional food systems, making them a ripe area for research. However, very little scholarly research has been carried out to characterize, contextualize or evaluate agrihood developments. Thus far, the development model has primarily been detailed in popular media sources. This thesis serves as a baseline study that seeks to understand how neighborhood food systems operate within agrihood developments and how residents engage with their agricultural amenities.

A mixed-methods approach utilized an online survey for agrihood residents and interviews with developers and farm managers to describe a subset of agrihoods as case studies. Seventy-eight agrihoods were identified; six were selected for case study analysis, three of which provided results for the resident survey (n=388). Survey results indicate that the character of the community was a more important motivator for agrihood residents to move to their community compared to the agricultural amenities. While all case study agrihoods sell produce directly to consumers through a CSA, farm store, or both, few survey respondents indicated they were CSA members or regularly shopped at the neighborhood farm store, with cost and convenience identified as the biggest barriers.

While resident engagement with the neighborhood farm may be limited, charging an annual resident fee to support the farm – an approach taken by four out six case study communities – may provide a guaranteed revenue source to the farm amidst low levels of resident engagement with the agrihoods’ sales outlets. Interviewees provided insight into the nuances of operating agrihood farms, enhancing resident engagement, and the spatial design of communities. The results of this thesis can help agrihood developers and managers, and land-use regulators to further understand this new development model. Furthermore, the findings in this thesis provide avenues for future research on how agrihoods contribute to farmland preservation and local and regional food systems.

1. Continue to identify, inventory, and investigate agrihood projects and add projects to the map on my website, www.agrihoodinfo.com, which already includes 70 projects.

2. Identify a subset of agrihood projects suitable for further investigation which have been lived in for more than 3 years and span the spectrum of size, context, and type of agriculture practiced.

a. Within the subset. develop and execute an online questionnaire geared towards agrihood residents.

i. the role of agriculture in them moving to the neighborhood,

ii. engagement with the agricultural components of the community,

iii. consumption and purchasing of food from the community farm, and

iv. sense of place and belonging within the community

b. Within the subset, develop and execute semi-structured interviews with agrihood developers, farmers, and managers, covering the following themes.

i. Agrihood Developers

1. Site history and land acquisition

2. Decision to include agriculture

3. Land protection and conservation, use of agricultural easements, and spatial design of community

4. Role of agriculture consultants in the deign process and how type of agricultural amenities were decided

5. Organizational structure and partnerships, management of farmland, educational events, CSA, and farmer’s market

6. Financial information, including real estate performance, upfront costs for agricultural amenities and expected payback period.

7. Transition from developer management to homeowner association (HOA) or lifestyle manager

ii. Agrihood Farmers

1. Professional background and agriculture experience

2. How and why they began working at the agrihood

3. Benefits and challenges of farming with sustained engagement from community

4. Role as agriculture educator, communicator, and event planner

5. How decisions are made for what to plant and when to harvest

6. Management of sales outlets, including farmer’s market, CSA, and/or farm stand

7. What they wish they knew when they first started at agrihood

iii. Agrihood Managers (Homeowner association president or lifestyle manager)

1. Business structure of community management

2. Revenue sources (HOA fees, property taxes, etc)

3. Relationship with and responsibility for farmland and other neighborhood amenities

c. For each community within the subset, develop a series of maps and diagrams, which help visualize the land use, integration of agriculture within the community, and the surrounding context.

3. Transcribe and analyze interviews and identify emerging patterns and themes

4. Describe each community as a unique case study, rich with quotes and insights, in a nicely formatted publication.

Agricultural-focused development, or the agrihood is a rising trend in North American real estate, which situates single and multifamily homes and community buildings within a landscape of edible plants, community gardens, and working farms. Defined as “single-family, multi-family, or mixed-use communities with a working farm or community garden as a focus” (Norris 2018), according to the Urban Land Institute, there are estimated to be 200 agrihoods in the United States and Canada, either built or in the development stages, with many of those projects currently in planning or early development phases (Donnally, 2015). These neighborhoods have proven to be desirable places to live for a wide array of people and household types. Agrihoods span the urban and rural context and vary in scale, types of agriculture, and organizational structure. What they share in common though is that agrihoods integrate food production, such as farms, gardens, orchards, greenhouses, or edible landscaping directly into the residential development and engage residents with locally and sustainably produced food and farming through educational events, volunteering on the farm, and personal garden plots.

By bringing agriculture directly to where people live and developing a deliberate relationship between the farm and residents, agrihoods possibly present a solution to numerous problems in affecting both the environment and human health. First, in many urban and suburban areas, there is geographic separation between local food producers and residential areas, such that consumers need to drive far to access CSAs and farmer’s markets and farmers transport food over long distances to access markets in denser areas. Second, agrihoods present exciting, new job opportunities for farmers, farm educators, food systems planners, and agricultural designers and consultants. Many of the existing agrihoods have a staff ranging from one farmer to dozens of farmers, educators, and sales staff. As the average age of farmers steadily rises, agrihoods provide an opportunity for young farmers to enter the industry because working for an agrihood reduces start-up costs and provides a committed, engaged marketplace (the residents) surrounding the farm. Thirdly, from a community resilience perspective, under threat of a changing climate sending shocks to the food system by way of extreme weather, pests, and disease, producing a diverse array of food at a neighborhood scale buffers against food shortages and makes the community less reliant on the global, industrial food system. Many agrihoods also include solar energy production, efficient homes, and protected conservation land.

The purpose of this project is to advance current knowledge about agrihood developments. The agrihood model presents an alternative to traditional development which supports, rather than displaces farmers, and allows residents to become engaged food consumers without geographic barriers. There is very little information about agrihoods in terms of how they function, the story behind each one, and how they are designed. My contribution will help agrihood developers, farmers, consultants, and managers learn from each other and spread their knowledge and experiences to those unfamiliar with the concept.

Justification

My thesis explores a new and growing topic which is important for urban planners, real estate developers, and the agricultural community to understand. In doing so, I will present new information for which there is a significant and demonstrated need. Agrihoods are a recent and understudied phenomenon and are only growing in popularity. This type of development potentially holds promise for bringing sustainable agriculture directly to where people live, supporting, rather than displacing farmers, and providing new job opportunities.

This is a ripe area for interdisciplinary research and my thesis can be one of the first to capture this growing movement and set a baseline for a development pattern which is likely to become more common. My research builds off the report produced by the Urban Land Institute (ULI; Norris 2018) titled Agrihoods: Cultivating Best Practices. This report presents a set of best practices for agrihood developers for topics such as land acquisition, farm management, and financial sustainability. The report is comprehensive in that it covers a range of topics but is limited in the sense that it applies only to developers, focuses on large-scale, subdivision style agrihoods, and provides broad lessons learned as opposed to specific approaches to various challenges.

I believe there is a demonstrated need for my research for a few reasons. First, within the agrihood community, whether it be the ULI report authors, agrihood developers whom I’ve met or spoken to, or other agrihood researchers, all have expressed the need for more research which characterizes and analyzes this trend. Second, based on my coursework and attendances at conferences, agrihoods are not part of the sustainable agriculture conversation or lexicon yet, despite holding promise to promote and grow opportunities for farmers. My project will seek to raise awareness of this idea to the sustainable agriculture community. Finally, within my field of study, urban design and planning, food and agriculture, are rarely part of the discussion or decision-making process, which has contributed to issues such as food deserts and the separation of agricultural and residential land uses in the zoning code. My research will potentially demonstrate a means by which agricultural and residential areas can not only integrate harmoniously but reinforce and support one another. I see my research bridging the gap which exists between urban planning and design and sustainable agriculture. In studying agrihoods, my project explores a new and growing topic for which there is a demonstrated need for farmers, the wider

Research Questions

- What is the local food system within agrihoods?

- To what extent do residents interact with and how important are the food and farming amenities?

Research

Methods

A mixed-methods approach was taken for this study including analysis of agrihood spatial design and qualitative research on agrihood residents and neighborhood food systems. Through this approach, each agrihood can be presented as a case study including descriptive analysis of size, population, density, farm acreage to resident ratio, and general spatial design as well as an understanding of the neighborhood history, the relationship between residents and the local agriculture, and the neighborhood food system. These case studies can then be compared and contrasted to gain a fuller understanding of the variation within agrihoods and the relationship between spatial design and resident engagement with the local food system. To begin, potential agrihood case study communities were identified using social media and other online sources. Secondly, a subset of potential agrihoods were selected as case study communities based on characteristics including maturity and amenities. Next, an online survey was administered to residents in order to gauge the extent to which residents interact with and the importance of the food and farming amenities in each agrihood. Concurrent to the survey, semi-structured interviews were carried out with agrihood developers, farmers, and manages in order to understand the local food system within each neighborhood. Throughout this whole process, social and physical data on each agrihood was collected in order to understand the spatial design and density characteristics.

Identify Potential Agrihood Case Studies

Potential agrihood case study communities were identified through the internet and communication with other people involved in the research, design, development, and management of agrihoods. Google searches for the terms: (agrihood or agri-hood) + (development, neighborhood, community, agriculture) were utilized to discover mentions of specific communities within news articles or the community website itself. Facebook and Instagram were searched using the hashtags #agrihood and #agrihoods to discover communities. The list of potential case study communities was then cross checked with a list of agrihood communities collected by the Urban Land Institute, available online at: https://americas.uli.org/research/centers-initiatives/building-healthy-places-initiative/food-real-estate/. For each community, their website was thoroughly reviewed as well as any news articles written about the community. Information about the community, such as the location, size, and amenities, was recorded in an Excel sheet for comparison. The agrihood definition provided by the Urban Land Institute was used to determine if a community should be considered an agrihood.

Identify Case Study Communities

From the larger list of agrihood communities collected previously, a subset of communities was identified to investigate further as case study communities. A stratified sampling method was utilized, which is sampling from a population which can be partitioned in to subpopulations. This was done in order to explore variety within agrihoods, including size, context, and maturity. Agrihood communities were categorized by context (urban, suburban, or rural), size (less than 10 acres, 10-500 acres, or greater than 500 acres), and by development maturity (planning stage, development stage, or year completed). For the purposes of this study, only agrihoods which were built and have had residents living in them and active agricultural amenities for at least 2 years were considered as case study communities.

Collect Data and Create Maps for Case Study Communities

Information on each case study community was collected by reviewing news article, neighborhood websites, final site plan documents, and through conversations with neighborhood officials. For each community information on the total acreage, acreage by land use type, including residential, commercial, agricultural, recreational, and conservation, resident populations, number of units, housing type, and the location and type of agricultural amenities was collected. By overlaying the master site plan provided by each community with aerial imagery provided by Google Earth, neighborhood maps were created using Adobe Illustrator, highlighting the relative location of structures, roads, trails, water, farm land, recreation land, and conservation land.

Administer Online Survey for Agrihood Residents

An online survey for agrihood residents was created using Qualtrics software in order to gauge the extent to which residents engage with food and agricultural amenities and the importance of these amenities in them moving to the neighborhood. The survey methodology was approved by the University of Massachusetts Institutional Review Board (IRB). For each community, a contact person was identified from their website, such as the developer, lifestyle manager, or home-owner’s association (HOA) chairperson. This person was then contacted to ask whether they could assist in administering the survey to residents within the community. Per the approved IRB protocol, the email list of residents could not be provided to me directly such that the developer or HOA were relied on to send the survey out to residents. Initial contact about the survey was made with each case study community on October 26th, 2019 and the survey was sent out to each community on different dates.

Perform Semi-Structured Interviews with Agrihood Developers, Farmers, and Managers

Interview questions were developed for agrihood developers, farmers, and managers in order to understand the local food system within each agrihood. The questions seek to understand how the farm is funded, how and where food is sold, and how residents are meant to interact with the actual production of food. The semi-structured interviews were carried out over the phone and were recorded. Conversations were allowed to flow organically but the conversation was steered back to the original interview questions. This approach allows for specific dimensions of the research questions to be explored while leaving flexibility for the participants to offer new meaning to inform the data. Semi-structured interviews are particularly important in mixed methods research by allowing for focused, two-way communication which adds depth, nuance, and meaning to the other qualitative data collected. The identity and contact information for these developers, farmers, and mangers is easy to find online a database of contact information has already been created.

Seventy-eight agrihood communities were discovered and documented through searches online and via social media. Of these seventy-eight agrihoods, the majority, 58% were considered to be in a suburban context, while 21% were in a rural context, and 21% in an urban context. Consistent information could not be gathered for total neighborhood size, number of units, or farm acreage, making comparison across the seventy-eight difficult. The most common agricultural amenities included working farms, community gardens, and orchards. Working farms were incorporated into 72% of the agrihoods identified, while 46% included community gardens, and 18% included orchards.

Map of case study communities

The case study analysis of six agrihoods provides insight into the physical characteristics, the location, the history, and the management structures of agrihoods around the country. The six agrihoods include the three at which the resident survey was administered – Willowsford, Harvest Green, and Agritopia – and three additional communities - Creekside Farm, Aberlin Springs, and South Village.

The farm management structure employed in each agrihood describes the relationship of the various actors involved in the neighborhood food system, with a focus on tracking the flow of money and food within the agrihood and to the surrounding community. An analysis of the farm management structures in each agrihood indicated that there were nearly as many farm management structures as there were agrihoods studied. The variations are all similar in the sense that an entity closely related to the developer or the development, whether it be the HOA, neighborhood conservancy, neighborhood farm market, or affiliated non-profit, owns the farmland itself. In none of the agrihoods studied did an outside entity, such as a private farmer, own the land itself. However, the entity which managed the farm, sales outlets, and programming differed within each farm as did the relationship between the managing entity and the farm owner.

|

|

Farmland Owner |

Farmland Management |

All Residents Pay Fee to Support Farm? |

|

Aberlin Springs |

Neighborhood Farm Market |

Private Farm Enterprises |

Yes |

|

Creekside Farm |

Developer |

Developer |

No |

|

South Village |

Neighborhood Conservancy |

Local Non-Profit |

Yes |

|

Agritopia |

Affiliated Non-Profit |

Affiliated Non-Profit |

No |

|

Harvest Green |

HOA |

Farm Amenity Management Company |

Yes |

|

Willowsford |

Neighborhood Conservancy |

Neighborhood Conservancy |

Yes |

The six agrihood case study communities vary in total size, number of units, and the amount of acreage dedicated for the working farm and non-agricultural open space. Willowsford is the largest community by far, encompassing a total of 4,125 acres, 300 of which are farmland, and is planned for 2,195 single-family homes. On the contrary, Creekside Farm is the smallest community, with 20 acres total, a 6-acre farm, and is planned for 18 single-family homes. The amount of developed acres for each community was calculated by subtracting the amount of farmland and non-agricultural public recreation and conservation land from the total acreage.

The net density is a measurement of the number of developed acres per unit in the community. Agritopia is the densest community, with just over a tenth of an acre per unit. This includes a senior living facility, cottage-style homes, and a mixed-use building with apartments having just broken ground but included in this analysis. Willowsford is the least dense community with over 1.8 acres per unit.

This information can be used to draw comparisons between the communities on their density and percentage of the community dedicated to the working farm. Aberlin Springs has the highest percentage of acreage dedicated to farmland at 35%, with Creekside Farm close behind with 30%. All the other communities have less than 12% of their total acreage in farmland. Aberlin Springs and Creekside Farm also have the highest ratio of farms acre per unit, with roughly a third of an acre of farmland per unit. This is over thirty times more farmland per unit than Harvest Green, where there is roughly a hundredth of an acre of farmland per unit.

The resident survey was administered to three agrihoods communities – Willowsford, Agritopia, and Harvest Green. A total of 388 survey responses were received out of an estimated 3,225 households from which were asked to take the survey for an estimated response rate of 12%.

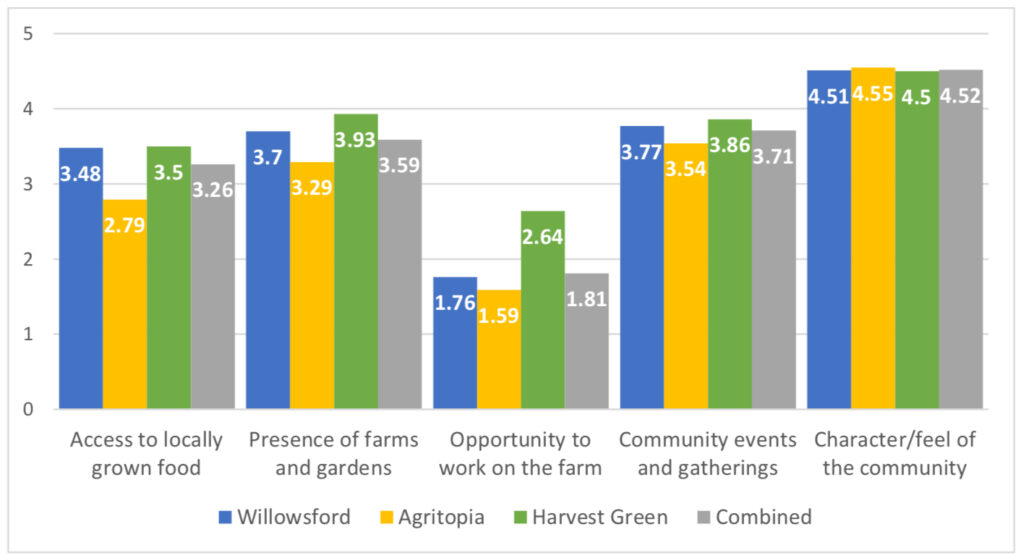

The character/feel of the community was the most important motivator for respondents deciding to move into their agrihood across all three communities, with a result of 4.5 or above for each community, indicating strong agreement. The opportunity to work on the farm was the least important motivator for respondents in each community, with a combined result of 1.81, which is below ‘slightly important’. Looking at the combined results, the second most important motivator were the community events and gatherings, followed by the presence of farms and gardens, and then access to locally grown food. So, while the community events and gatherings may include some agricultural-related programming, overall, the agricultural amenities were viewed as less important of a motivator than the character of the community and the events and gatherings.

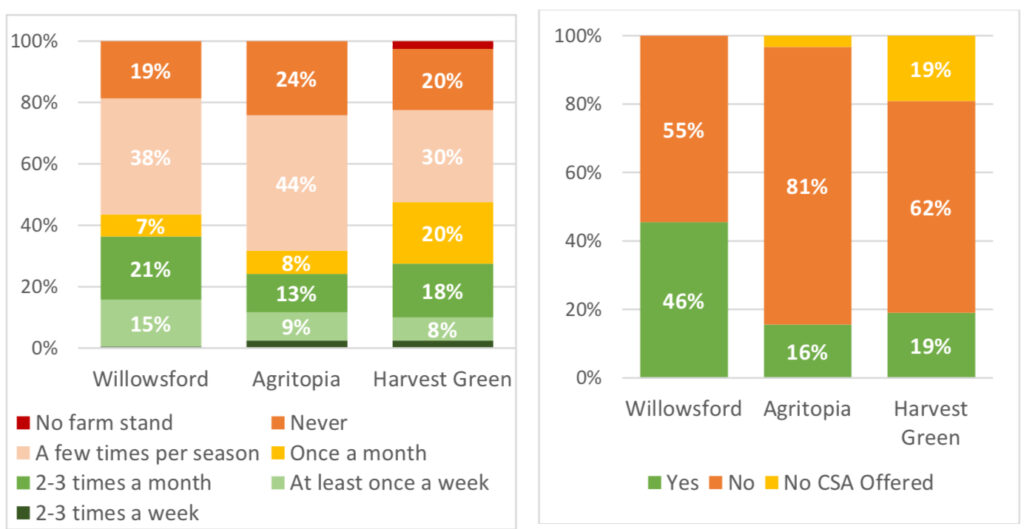

Survey results indicate that purchasing of neighborhood-produced food by residents is not the norm or quite low depending on the agrihood and sales outlet. Of the CSA programs, Willowsford boasted the highest level of participation from respondents at 46%, while Harvest Green was 19%, and Agritopia was 16%. In fact, the CSA program at Harvest Green has been suspended in the past year due to a lack of interest according to interview correspondence with a farm representative. Each agrihood surveyed also has a farm stand or farm market which sells local produce and respondents were asked about the frequency with which they visit their neighborhood farm store. Regular shopping at the farm store (at least once a month) was highest at Harvest Green, with 48% of respondents indicating they do so, compared to 32% Agritopia and 44% at Willowsford (Figure 9). Regular shopping at the farm store was higher than CSA membership across all neighborhoods, except Willowsford, where 43% of respondents regularly shopped at the farm store versus 55% of respondents who were CSA members.

The biggest barriers to farm store visitation and CSA membership generally differed from one another and between neighborhood, however, there were similarities as well. The barriers to CSA membership were similar across all three neighborhoods, with the most respondents in each agrihood indicating membership was too expensive, thus cost was the biggest barrier. However, for farm store visitation, the biggest barriers differed across communities, with convenience the biggest barrier in Willowsford and the lack of options the biggest barrier in both Agritopia and Harvest

Green.

In contrast to the biggest barriers, the most important motivators for CSA membership and farm store visitation highlight the reasons why respondent did choose to purchase neighborhood-produced food. Across all three agrihoods and both sales outlets, supporting local farmers was the most important motivator for purchasing neighborhood produced food. Health and taste were also important motivators for CSA membership and farm stand visitation, indicating respondents value eating neighborhood food both as a benefit to themselves but also to the community farmer.

The resident survey and case study analysis highlighted some of the key similarities and differences between the agrihoods in their development history, physical characteristics, and business structure, but also in levels of resident engagement with agricultural amenities. One of the patterns which emerged from the resident survey was the residents’ lack of engagement with their neighborhood’s agricultural amenities–specifically CSA membership, farm store visitation, and volunteering. The resident survey also suggested that the agricultural amenities within the agrihood were not the most important factor in residents’ decision to move to that neighborhood, and that perhaps the general character of the community was most important. However, residents generally felt a high level of satisfaction and attachment to their neighborhood. The case study analysis shed light on the differences in the management structure of each agrihood and the different histories surrounding each community.

This thesis serves as a baseline study, presenting some of the first empirical research on the agrihood trend, with a focus on how the neighborhood food systems take shape within agrihoods and how residents engage with agricultural amenities. The results of this research can help situate the agrihood development model within the context of farmland preservation and local and regional food systems. More practically, the results of this research can also help developers, land-use planners, landscape designers, farm managers, and prospective agrihood residents understand how these neighborhoods operate and how other agrihoods have addressed some of the challenges associated with managing a neighborhood food system. The main conclusions taken from this thesis include:

- Agrihoods are generally located in suburban areas and the six agrihoods in this study were all developed on land formerly used for agriculture.

- While four out of six agrihoods permanently protect their farmland, the amount of farmland in the community varies by orders of magnitude amongst the six.

- The six agrihoods employ a variety of business structures to manage the agricultural amenities, with four using resident fees to supply a guaranteed cash flow to the farm and two relying on sales revenue alone to support the farm.

- All six agrihood farms produce a variety of fruits and vegetables, sell through direct-to-consumer outlets such as a CSA, farmers’ markets, or farm store, and make food available to both agrihood residents and the surrounding community.

- For most residents, the most important motivator in their decision to move to the agrihood was the character/feel of the community, not the agricultural amenities.

- Interviewees expressed that residents are generally very busy and survey respondents indicated convenience was a large barrier for residents engaging with the farm, both in terms of food purchasing, farm events, and volunteering.

- Interviewees expressed that agrihood farmers and farm staff need to be highly skilled and able to undertake all the agricultural responsibilities but also manage events and activities with residents.

As demand for quality urban and suburban housing continues to increase, agrihoods can be seen as a development model which may be able to alleviate the tension between housing and farmland preservation and also contribute to local and regional food systems. Land-use regulators and real estate developers may want to consider a set of standards and thresholds for neighborhoods to be considered agrihoods. This could help developers differentiate their communities by limiting the term agrihood to only those developments which include a certain percentage of farmland, agricultural programming, and sales outlets. Likewise, land-use regulators may want to consider zoning tools for subdivision development along the rural-suburban interface where developers can receive incentives for the integration of farmland into their developments and the permanent protection of farmland and open there within. The specific amount of farmland and the tools used for protection can be left for local officials to determine but this thesis suggests that there is great deal of variation in the amounts of farmland and the tools used for protection within the subset of agrihoods studied.

This is new phenomenon and as results of this thesis show, a nuanced and complex development model and relationship between agrihood residents and the neighborhood food system. This is ripe area for further research across a broad spectrum of disciplines. This thesis serves as a baseline study with a wide-ranging focus on the development history, physical characteristics, and business structure for a subset of agrihoods and also how residents engage with and think about the agricultural amenities. Further research could go more in-depth or expand on any of the topics discussed in this thesis, but more specific recommendations have been provided throughout the conclusion section.

Agrihoods represent a development model with important implications for farmland preservation, local and regional food systems, and housing. Moreover, in a historical context, beginning with greenbelt towns, to post-war suburbs, New Towns, conservation subdivisions, and finally to the local foods movement of the last few decades, the agrihood phenomenon can be seen as the latest iteration of people wanting to relate to and live in conjunction with food production and open space. This is development model which seems poised to grow as the majority of developments have been built or broken ground in the past few years. Looking forward, agrihoods may be able to contribute to farmland preservation and local food systems in a significant way or be more akin to a superficial marketing tool used by developers to differentiate their communities. As more agrihoods break ground and open to residents, only time and further research will tell where agrihoods lie along this spectrum. Regulators and developers, along with citizens, have a role to play in guiding this development model towards a desirable outcome for all parties.

Education & Outreach Activities and Participation Summary

Participation Summary:

Consulted with agrihood farm managers about the best practices I had learned from discussions with agrihoods. Presented the results of my thesis to my department.

Project Outcomes

This project describes a trend in real estate called the ‘agrihood’ which situates sustainable agriculture into planned residential neighborhoods as an amenity for residents. In growing metro areas with farmland on the fringes, the agrihood development model could present an alternative solution for farmers faced with selling their farmland for housing development. The agrihood could allow for farmers to retain some of their farmland, sell some for a profit, and gain an engaged market for their product in the form of the new residential neighborhood. This development model enhances farmland preservation, local and regional food systems, and support small-scale, typically organic farming methods.

This research advanced knowledge and changed attitudes about the relationship between sustainable agriculture and residential development. These two land uses had previously been seen as largely non-compatible, however, further investigation into the ‘agrihood’ development model has shown how these two land uses can be integrated and supportive of one another. Sustainable agriculture is a desirable amenity for residents to live near indicated by the high levels of satisfaction and place attachment residents felt towards their communities. In four of the neighborhoods, residents pay an annual fee to support the community farm irrespective of how much produce they buy from the farm. This baseline study provides some indication that agrihoods can preserve farmland and contribute to local food systems.

As I continue my career path in urban planning and design, the knowledge and awareness gained through this research will always stay with me. I intend to be involved with agrihood projects in the future – through continued research, outreach, or consultations.