Final report for GNE21-266

Project Information

This project aimed to address the challenges and barriers faced by Hispanic/Latinx farmers in the Northeast United States, particularly within the context of sustainable agriculture. Despite their growing presence, Latinx farmers remain an underserved group in agricultural policy and practice, often framed predominantly as farmworkers rather than farm owners. This framing limits their access to resources, representation, and support necessary for establishing and maintaining sustainable farming operations. The project sought to explore the institutional frameworks supporting Latinx farmers, identify factors contributing to successful development programs, and understand the challenges these farmers face.

The research employed a qualitative approach, focusing on staff members of organizations that provide services to Latinx farmers. Initially, the project aimed to interview farmers directly, but due to the difficulties in accessing this hard-to-reach population, the focus shifted to institutional perspectives. A total of 40 in-depth interviews were conducted via Zoom, with participants representing a variety of organizations, including NGOs, land-grant institutions, and community-based groups across Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts. The interviews, averaging 46 minutes in length, explored how organizations framed their work, the farmers they served, and the needs of the farming community. Coding and analysis of interview transcripts provided insights into the systemic and operational dynamics affecting the success of development programs.

The study concluded that culturally and linguistically tailored services are vital for effectively supporting Latinx farmers. Organizations that offered bilingual resources, employed Spanish-speaking staff, and demonstrated cultural sensitivity fostered trust and engagement with the farming community. However, challenges such as systemic discrimination, language barriers, and limited resources persist. Organizations often face structural constraints, such as underfunded programs and reliance on individual champions for diversity initiatives, which limit their ability to deliver sustained and equitable support. Moreover, the framing of Latinx farmers as aid recipients rather than active contributors to agricultural innovation diminishes their agency and perpetuates marginalization.

An important outcome of this research is the identification of strategies to overcome these barriers. Advocacy for policy reforms, such as land access programs and equitable funding opportunities, emerged as a crucial step toward addressing structural inequities. Additionally, leveraging community-based networks and trusted local leaders proved effective in bridging gaps between institutions and farmers. The study also emphasized the need for hybrid approaches to outreach, combining digital tools with in-person engagement to ensure inclusivity.

The project’s findings have significant implications for the agricultural community. By reframing Latinx farmers as active participants and leaders in sustainable agriculture, institutions can enhance their contributions to ecological farming practices and food system resilience. The research highlights the need for systemic changes in policy and institutional support to better address the unique challenges faced by Latinx farmers. Investing in culturally appropriate outreach, fostering trust, and advocating for equity in resource allocation can strengthen the sustainability and inclusivity of agriculture in the Northeast.

Unexpectedly, the shift in focus from farmers to institutional representatives provided a deeper understanding of the systemic barriers within organizations themselves. This pivot also revealed the potential for organizations to serve as critical allies in addressing these challenges. The lessons learned from this project underscore the importance of community-centered research and the need for sustained efforts to ensure Latinx farmers are recognized and supported as integral contributors to sustainable agriculture.

The original aims of this project were to:

- Identify the economic, production-related, informational, and educational barriers Latino/a farmers face in establishing a profitable, sustainable farming enterprise and the strategies they use to overcome those barriers.

- Develop a better understanding of Latino/a farmers' aspirations and desires to enter commercial markets for sustainable agriculture by scaling up and expanding their farm businesses.

- Identify the paths that Latino farmers have followed to become sustainable farm owners and the relevance of masculine identities in facilitating and/or constraining the process.

- Provide sustainable agriculture organizations supporting Latino/a farmers in Pennsylvania, specifically Penn State Extension and PASA, with evidence-based recommendations designed to support successful farming production to improve the quality of life for Latino/a farmers in the sustainable agriculture sector.

Despite extensive outreach efforts, challenges arose that prevented collecting sufficient data directly from Latino/a farmers. Recruitment difficulties, including limited access to the target population, time constraints, and logistical barriers, hindered the ability to engage a representative sample of Hispanic farmers in Pennsylvania.

To address these challenges and ensure the project’s continued relevance, the research focus shifted to individuals working for organizations supporting Latino/a farmers, including NGO and Land Grant Extension officers across Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts. This adaptation allowed the project to examine how these organizations address barriers faced by Latino/a farmers, support their aspirations for scaling up farm businesses, and facilitate their pathways toward sustainable farm ownership. By expanding the scope to a regional perspective, the project provided broader insights into the role of support organizations and retained its commitment to improving outcomes for Latino/a farmers. The findings also offer actionable recommendations for sustainable agriculture organizations, including Penn State Extension and PASA, to enhance their support strategies and practices.

With these shifts, the project objectives were reformulated to reflect the new focus. The updated objectives are:

- What factors contribute to the success of development programs and projects directed to farmers of Hispanic/Latinx origin, what challenges have they faced, and what strategies have they followed to overcome those challenges?

- How do institutions supporting Latinx farmers frame their work, the Latino farmers they work with, and their needs? What are the consequences of these discourses?

This refined focus enabled the project to explore the institutional and systemic aspects of support for Latinx farmers, contributing valuable insights for improving sustainable agriculture programs across the region.

This study examined how organizations support Latino/a farmers in overcoming barriers to participation and success in sustainable agriculture in the Northeast. Latino/a farmers are the fastest-growing ethnoracial producer group in the U.S. (USDA-NASS, 2019). Latino/a producers face numerous challenges as farm owners that hinder their ability to achieve successful farming operations. These challenges include restricted access to start-up capital, working funds, land, labor, and markets (Swisher et al., 2007). Additionally, these barriers are compounded by intersecting factors such as citizenship status, ethnoracial disparities, linguistic limitations, and educational constraints (Minkoff-Zern, 2019). Examining how organizations address these multifaceted challenges and adapt their services to meet the specific needs of Latinx producers is essential for developing effective and equitable support systems. The challenges faced by Latino/a farmers underscore the need for targeted organizational support to empower them and establish viable and sustainable farming enterprises.

Organizations, ranging from government agencies to non-profits and community-based groups, play a pivotal role in shaping the support available to Latinx farmers. The growing presence of Latinx farmers signals a positive trend toward inclusivity in agriculture. However, this increase highlights critical questions about their access to essential farming resources, including land, capital, and market opportunities. To address these barriers, organizations such as NGOs and Land Grant Extensions can play a critical role in providing economic, educational, and informational resources tailored to the unique needs of Latina/a farmers. This support is particularly significant, as Latino/a farmers actively contribute to the sustainable agriculture movement through practices rooted in ecological farming principles and their cultural connection to land stewardship (Minkoff-Zern, 2019).

Literature on Latinx farmers in the U.S. remains limited. While existing studies have primarily focused on the challenges and barriers faced by Latino/a farmers (Huerta-Arredondo et al., 2023; Minkoff-Zern 2018; Minkoff-Zern 2017; Minkoff-Zern 2014; Thompson, 2011), fewer have examined the organizations that provide support to this population, particularly NGOs and Land Grant Extension Services (Bittner, 2019; Huerta Arredondo, 2020; Huerta Arredondo et al., 2017). This study centers on the organizations serving Latinx farmers in Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts, analyzing the factors contributing to the success of their programs, the challenges they face, and the strategies employed to overcome these obstacles. By doing so, this research provides critical insights into how organizations frame their work, the farmers they serve, and the needs they aim to address, offering evidence-based recommendations to improve organizational practices and better support Latino/a farmers sustainable practices.

Through in-depth qualitative interviews, this research sought to address the following questions:

- What obstacles do Latino/a and Hispanic farmers face as they transition to owning and managing successful sustainable farming operations, and what strategies do they employ to overcome these obstacles?

- What are their aspirations concerning scaling up and entering commercial markets for sustainable agriculture?

- How do rural Latin American masculinities become reproduced or reshaped in the U.S. as they establish themselves as sustainable farmers, and how does this impact the ability of women and men farmers to meet sustainability goals?

However, recruitment challenges and lessons learned during the search for participants necessitated a shift in focus. As a result, the research questions were reformulated to align with the updated direction toward studying Latinx farmer-serving institutions. The revised research questions are:

- What factors contribute to the success of development programs and projects directed to farmers of Hispanic/Latinx origin, what challenges have they faced, and what strategies have they followed to overcome those challenges?

- How do institutions supporting Latinx farmers frame their work, the Latino farmers they work with, and their needs? What are the consequences of these discourses?

These changes were proposed in response to the challenges encountered and aimed at leveraging the flexibility of the research approach to address the updated questions. The proposed shift and continued use of funds to adapt the study’s focus were consulted with NESARE to ensure alignment with project goals.

References:

Bittner, L. (2019). Meeting needs of the people: a multi-case study of New Mexico extension professionals’ cultural competence in reaching historically under-served populations. New Mexico State University.

Huerta-Arredondo, I. A., Sánchez, E., & Ewing, J. (2023). Understanding Latinx Farmers in Pennsylvania to Meet Their Needs for Non-Formal Education. Horticulturae, 9(5), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9050590

Huerta Arredondo, I. A. (2020). An exploratory approach to study latino/a farmers in Pennsylvania and the role of cooperative extension. The Pennsylvania State University.

Huerta Arredondo, I. A., Miller-Foster, M., & Gorgo-Gourovitch, M. (2017). Hispanics’ Knowledge of the Land Grant Mission in the Mid-Atlantic. Nacta Journal, 61(Supplement 1), 57–58.

Minkoff-Zern, L.-A. (2018). Race, immigration and the agrarian question: farmworkers becoming farmers in the United States. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(2), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1293661

Minkoff-Zern, L.-A. (2019). The New American Farmer: Immigration, Race, and the Struggle for Sustainability. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11263.001.0001

Minkoff-Zern, L.-A., & Sloat, S. (2017). A new era of civil rights? Latino immigrant farmers and exclusion at the United States Department of Agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values, 34(3), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9756-6

Minkoff-Zern, L. A. (2014). Knowing “good food”: Immigrant knowledge and the racial politics of farmworker food insecurity. Antipode, 46(5), 1190–1204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01016.x

Swisher, M. E., Brennan, M., & Shah, M. (2007). Final Report: Hispanic-Latino Farmers and Ranchers Project.

Thompson, D. (2011). “Somos del Campo”: Latino and Latina Gardeners and Farmers in Two Rural Communities of Iowa — A Community Capitals Framework Approach. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 1(3), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2011.013.001

USDA-NASS. (2019). Race/Ethnicity/Gender Profile.

Research

This study utilized a qualitative design, specifically in-depth interviews, to address the following questions:

- What factors contribute to the success of development programs and projects directed to farmers of Hispanic/Latinx origin, what challenges have they faced, and what strategies have they followed to overcome those challenges?

- How do institutions supporting Latinx farmers frame their work, the Latino farmers they work with, and their needs? What are the consequences of these discourses?

Respondents were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling methods. Purposive sampling (Bryman, 2012; Mathison, 2013), was employed to identify participants with relevant experience and perspectives on programs and projects directed at supporting Hispanic/Latinx farmers in the Northeast, specifically in Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts. Snowball sampling was used to expand the participant pool through referrals from initial informants (Frey, 2018). Participants were selected based on their involvement in organizations or institutions supporting Latinx farmers, rather than being farmers themselves. Recruitment materials, consent forms, and interviews were provided in Spanish or English, as appropriate, by the bilingual graduate researcher.

The in-depth interviews were voice-recorded with the proper permissions obtained from participants and subsequently transcribed. The transcriptions were coded and analyzed using NVivo software, employing a mix of thematic, structural, descriptive, and in vivo coding techniques (Bingham & Witkowsky, 2021; Saldaña, 2016). Structural coding was used to apply content-based phrases representing topics related to the research questions, while descriptive coding identified emerging topics within the data. In vivo coding was particularly valuable for capturing participants' exact words to "honor the participant's voice"(Saldaña, 2016, p. 106).

Interviews focused on the experiences of individuals working with or supporting Latino farmers, focusing on the challenges, strategies, and institutional frameworks shaping their engagement. The data were analyzed to explore the factors influencing the success of development programs, the framing of Latinx farmers and their needs by supporting institutions, and the implications of these discourses for equitable and sustainable support.

References:

Bingham, A. J., & Witkowsky, P. (2021). Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. In C. Vanover, P. Mihas, & J. Saldaña (Eds.), Analyzing and interpreting qualitative data: After the interview (pp. 133–146). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

Frey, B. B. (2018). Snowball Sampling. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506326139.n636

Mathison, S. (2013). Purposeful Sampling. Encyclopedia of Evaluation. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412950558.n453

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd Ed). Sage.

Respondents Sociodemographic Information

A total of 40 interviews were conducted via Zoom, with an average duration of 46 minutes per session. The in-depth interviews explored a broad range of topics aimed at understanding the support systems available to Latinx farmers and the challenges they face within the agricultural sector. The interviews began by gathering background information about the participants and their roles within institutions serving Latinx farmers. Participants detailed their professional experiences, the specific services their organizations provided, and how these were tailored to meet the unique needs of Latinx farmers. Additionally, the interviews delved into the origins of these services and the institutional adjustments made to comply with external regulations and funding requirements.

A significant focus was placed on understanding the barriers and challenges Latinx farmers face. Participants discussed the cultural, social, and economic obstacles hindering the success of these farmers. This included exploring how organizational programs addressed these barriers, examples of successful interventions, and gaps where improvements were needed. The interviews also examined whether the needs of Latinx farmers had shifted over time and the institutional responses to such changes, particularly during periods of political transition.

The interviews highlighted the opportunities and strengths that Latinx farmers bring to the agricultural sector, as well as the efforts of organizations to foster leadership, community, and networking opportunities among them. Participants shared success stories of Latinx-operated farms and discussed the role these stories play in shaping the vision of Latinx farmers' contributions to the broader food system in the Northeast. This included examining the institution’s efforts to promote these farmers’ strengths and enhance their visibility in the industry.

The theme of stakeholder engagement emerged as a key area of inquiry. Participants described collaborations and partnerships with other organizations, as well as the role of Latinx farmers and community representatives in shaping institutional decisions and service provision. The interviews probed how organizations incorporated feedback from stakeholders and the extent to which these interactions influenced organizational priorities.

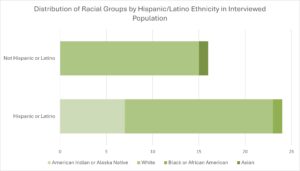

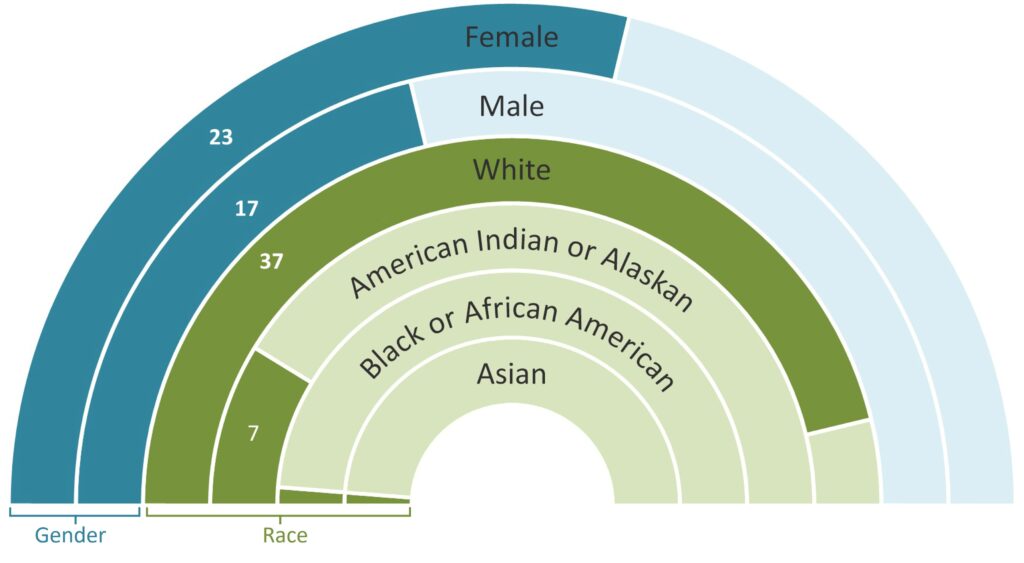

As illustrated in Figure 1, the study included a total of 40 participants, comprising 23 males and 17 females. Regarding racial and ethnic identity, the majority of participants (37) identified as white, followed by 7 as American Indian or Alaskan, 1 as Black or African American, and 1 as Asian.

Regarding language, 18 participants were native Spanish speakers, 8 were non-native Spanish speakers, and 14 did not speak Spanish. Among the Latino or Hispanic respondents, 16 identified as white, 7 as American Indian, and 1 as Black or Afro-Latino. The average age across all participants was 42 years old.

In addition, figure 2 provides insight into the racial and ethnic composition of study participants. However, it is important to contextualize how participants with Latino and indigenous roots navigated the categories provided for this study. Among the participants who identified as Hispanic or Latino, seven individuals selected the "American Indian or Alaska Native" category to reflect their indigenous heritage. These participants often represented first-generation Latin American extensionists with indigenous backgrounds. Their identification highlights the nuanced and complex interplay of ethnicity and racial identity in the Latino community.

It is noteworthy that the racial categories used in this study, such as "White" or "American Indian or Alaska Native," do not fully capture the ethnic and cultural identity of many Latino participants. For instance, several participants with indigenous roots might typically identify as "Mestizo," a term widely used in Latin America to denote individuals of mixed European and indigenous ancestry. Unfortunately, such a category was not included in the study’s racial and ethnic framework, leaving participants to choose from categories that might not entirely reflect their lived identities.

This limitation underscores the need for more inclusive and culturally relevant categories in research that involves ethnically and racially diverse populations, particularly when studying Latin American and indigenous communities. It also sheds light on the diversity within the Latino population, where racial identity is deeply intertwined with historical, cultural, and geographic factors.

Finally, figure 3 shows the locations and organizational types of the staff members who participated in the study. Most participants are based in Pennsylvania, with 23 organizations represented, primarily Land Grant Extensions, along with agri-focused NGOs and a few government agencies. New York follows with 11 organizations, also mostly Land Grant Extensions, and some representation from agri-focused NGOs. Massachusetts includes four organizations evenly split between Land Grant Extensions and agri-focused NGOs, while Washington D.C. has the smallest representation, with two participants from agri-focused NGOs. These findings reflect the organizations and locations identified through purposive and snowball sampling methods, providing insight into the types of institutions engaged in supporting Latinx farmers in these regions.

Success Factors, Challenges, and Strategies in Development Programs for Hispanic/Latinx Farmers

The voices of respondents working within development programs for Hispanic/Latinx farmers shed light on the factors contributing to program success, the challenges they encounter, and the strategies they use to navigate these obstacles. Their insights emphasize the importance of culturally and linguistically tailored services, trust-building between organizations and the farming community, and sustained support to address both immediate and long-term needs. At the same time, study participants highlighted persistent barriers such as language differences, systemic inequities, and resource limitations that require innovative strategies to overcome.

Respondents consistently underscored the value of tailoring services to the cultural and linguistic needs of Hispanic/Latinx farmers. They described how providing workshops and resources in Spanish and employing bilingual personnel helped build bridges between their organizations and the farmers they served. These efforts not only facilitated the dissemination of technical information but also created a sense of inclusion and respect for farmers’ cultural identities. One participant highlighted how the availability of Spanish-language materials significantly increased participation in training sessions, demonstrating the critical role of accessibility in engagement.

Building trust with farming communities was also described as a cornerstone of effective programming. Study participants explained that many Hispanic/Latinx farmers approach institutional support with skepticism, often shaped by historical or personal experiences of exclusion or discrimination. Establishing trust required consistent engagement, transparency, and a demonstrated commitment to the farmers' well-being. For example, one respondent shared how repeat visits and follow-up actions strengthened relationships with farmers, encouraging them to seek out assistance and openly share their challenges.

While these efforts have yielded successes, the respondents acknowledged substantial challenges. Language barriers continue to hinder communication when bilingual resources or personnel are unavailable. Study participants described how this gap impeded farmers' understanding of technical guidelines, application processes, and safety protocols, ultimately limiting their ability to access available resources. Furthermore, systemic inequities, such as discrimination in funding opportunities and restrictive land acquisition policies, were identified as major barriers. Respondents expressed frustration at the lack of institutional awareness or recognition of these issues, which often left farmers underserved.

Resource constraints within organizations were another persistent challenge. Study participants described how limited budgets restricted their ability to offer bilingual materials, hire additional personnel, or conduct extensive outreach in remote areas. These constraints were particularly felt in rural regions, where geographic isolation compounded the difficulties of connecting with farming communities.

Despite these challenges, respondents employed creative strategies to maximize their impact. Peer networks and partnerships with community leaders emerged as effective approaches to extend the reach of their programs. Many study participants shared how collaboration with trusted local figures helped bridge gaps between institutions and farming communities, fostering trust and ensuring that resources were appropriately distributed.

Advocacy also played a crucial role. Respondents described efforts to push for policies that promote equitable access to resources for Hispanic/Latinx farmers. These initiatives included advocating for land access programs, increasing funding opportunities, and enhancing representation in agricultural decision-making processes. Such advocacy was seen as essential for addressing structural inequities and ensuring long-term sustainability for the farmers they aimed to support.

Technology offered both opportunities and limitations. Respondents noted that virtual workshops and online resources allowed organizations to reach broader audiences, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, they also acknowledged that not all farmers had reliable internet access or the technical skills needed to benefit fully from these resources, underscoring the need for hybrid approaches.

Framing Institutional Support for Latinx Farmers: Narratives, Needs, and Consequences

Based on the interview data, institutions supporting Hispanic/Latinx farmers adopt diverse approaches to define their work, understand the farmers they engage with, and conceptualize the farmers' needs. These approaches reflect organizational missions, societal narratives about diversity and inclusion, and practical constraints in implementing outreach and support initiatives. Consequently, the ways institutions describe their efforts and their understanding of farmers' needs influence the effectiveness of their support and the overall relationship with the farming community.

One recurring theme was the emphasis on bridging linguistic and cultural gaps. Institutions frequently framed their work as a response to language barriers, positioning bilingual outreach and Spanish-language resources as central strategies. While this approach was often effective in addressing immediate communication challenges, some respondents suggested that an overemphasis on language could inadvertently perpetuate stereotypes, reducing the multifaceted experiences of Latinx farmers to linguistic differences alone. This simplification risks overlooking broader systemic issues, such as economic inequities or access to land and funding, which require more holistic interventions.

Trust-building emerged as a critical focus. Institutions often described their efforts to establish trust through long-term engagement, transparent communication, and culturally sensitive practices. Respondents highlighted that trust was particularly fragile within communities with historical or ongoing experiences of exclusion or discrimination by larger systems. The narrative of building trust often underscored the need for organizations to demonstrate genuine commitment beyond performative actions. For instance, respondents discussed how repeated engagement and consistent follow-ups fostered credibility and encouraged farmers to seek support or participate in programs.

Another significant framing centered on resource access. Institutions viewed their role as facilitating connections between Latinx farmers and essential agricultural resources, such as funding, technical training, and land access. However, many organizations faced structural limitations in fulfilling these objectives. Respondents noted that resource constraints and bureaucratic processes sometimes undermined the intended impact of these programs. Additionally, there were concerns that farmers were often framed as recipients of aid rather than active contributors to agricultural innovation—a perspective that can inadvertently diminish their agency and expertise.

Institutions also grappled with internal dynamics that shaped their ability to deliver meaningful support. Respondents described how diversity initiatives within institutions were frequently driven by passionate individuals rather than institutional mandates. This reliance on individual champions raised concerns about sustainability and scalability, particularly when these efforts were not integrated into broader organizational strategies. The framing of diversity and inclusion as secondary to core institutional goals often led to underfunded and fragmented initiatives, limiting their reach and efficacy.

The consequences of these approaches are significant. Positive framings, such as valuing cultural diversity and emphasizing collaboration, fostered inclusion and helped tailor programs to the specific needs of Latinx farmers. However, reductive or superficial narratives could perpetuate stereotypes, overlook systemic barriers, and alienate parts of the farming community. Moreover, the lack of sustained institutional support for diversity-focused initiatives left many programs vulnerable to changes in leadership or funding priorities. Addressing these challenges requires institutions to adopt more nuanced and integrated approaches that respect the complexity of Latinx farmers' experiences while fostering their empowerment and long-term success.

The findings from this study provide valuable insights into the critical elements needed to support Hispanic/Latinx farmers in the Northeast, particularly in fostering sustainable farming practices. The conclusions highlight key factors that organizations should prioritize to improve their programs and services effectively.

A primary takeaway is the importance of providing culturally and linguistically appropriate support. Many organizations have successfully engaged with Latinx farmers by offering Spanish-language resources and employing bilingual staff. These efforts help break down language barriers while also building trust and fostering stronger relationships with the farming community. Trust is a crucial foundation for program success, encouraging farmers to engage with available resources and share their challenges openly. However, the research also identified the need to address systemic barriers, such as limited access to funding, land, and markets, which extend beyond language-related challenges and require more comprehensive solutions.

Another important conclusion is the way organizations frame their work and the farmers they serve. Many programs focus on addressing the challenges farmers face but may unintentionally position them as passive recipients of aid. Recognizing and amplifying the expertise, resilience, and innovative practices of Latinx farmers is essential to their empowerment and success. By reframing these narratives, organizations can better highlight the significant contributions of Latinx farmers to sustainable agriculture and encourage their leadership in shaping the future of the sector.

The study also revealed persistent challenges for organizations in delivering effective support. Limited resources and funding were commonly cited issues, often restricting the scope and reach of services. This challenge is particularly evident in rural areas, where geographic isolation adds to the difficulty of reaching farmers consistently. To address these limitations, organizations need greater structural support and funding to scale their programs and improve access for farmers. Furthermore, diversity and inclusion initiatives within institutions often rely heavily on individual efforts, which raises concerns about sustainability. Embedding these initiatives into broader organizational priorities is critical to ensuring long-term success.

Advocacy emerged as a significant area for further development. Respondents emphasized the need for organizations to engage in policy work to address structural barriers, such as improving land access, expanding funding opportunities, and ensuring equitable representation for Latinx farmers in decision-making processes. Policy changes in these areas could have transformative impacts on the ability of farmers to thrive within the agricultural sector.

The role of technology in program delivery was another important finding. Virtual tools such as online workshops proved to be valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling broader outreach. However, disparities in digital access and literacy remain a challenge, particularly for farmers in remote areas. Organizations should consider hybrid approaches that blend in-person support with digital resources to ensure that all farmers can benefit from their programs.

In summary, the study underscores the importance of a multifaceted approach to supporting Latinx farmers in the Northeast. To enhance sustainable farming practices and promote equity, organizations need to combine culturally tailored outreach with systemic changes that address broader barriers. By focusing on trust-building, reframing narratives, securing adequate resources, and advocating for policy reforms, institutions can empower Latinx farmers to succeed and strengthen the sustainability of the agricultural sector. These efforts will not only support individual farmers but also contribute to building a more inclusive and resilient food system.

Education & outreach activities and participation summary

Participation summary:

This report, which will be publicly shared with members of participant institutions, represents one of the first steps in disseminating findings from this research.

In 2024, I presented part of the study's results at the Rural Sociological Society's (RSS) annual conference as part of a panel titled Beyond Immigration: Panel Discussion with Sociologists Who Work with Latino/a/e Communities. Additionally, I presented my research at the Rural Sociology Program Brown Bag series at Penn State, where I shared preliminary findings and engaged in discussions with colleagues.

Some outreach activities are still in progress. For example, I am collaborating with Penn State Extension’s Latinx Agricultural Network (LAN) to organize a webinar and share findings through their social media and other platforms. Findings will also be presented in Spanish and English through Penn State Extension’s on-demand webinar program. Additionally, I plan to present the results at the PASA 2026 conference, focusing on recommendations for sustainable agriculture organizations.

Data from the interviews is still being analyzed. These findings will be used to create evidence-based recommendations for agricultural organizations to help Latino/a farmers scale up their businesses and improve their quality of life. Once the analysis is complete, the results will be compiled into a report for distribution to research participants and organizational networks.

Finally, results from this research will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals, including Rural Sociology and Agriculture and Human Values.

Project Outcomes

The results of this study reveal several promising outcomes that could greatly enhance agricultural sustainability, benefiting Latino farmers economically, environmentally, and socially. These findings provide a strong foundation for future efforts to support Latino farmers more effectively.

Economic Benefits

This research shows that recognizing Latino farmworkers as potential farm owners, rather than just a workforce can unlock significant economic opportunities. By offering comprehensive support services, such as business planning, financial management, and market access, Latino farmers can be better equipped to start and grow their agricultural businesses. For example, the successful model of the Massachusetts Agri-focused NGO's partnership with UMASS could be replicated, helping Latino farmers gain access to financing and build stronger market connections, leading to increased profitability and economic stability. Additionally, providing mileage reimbursement can help ease the transportation burden, making it easier for farmers to attend training sessions and access vital resources.

Environmental Benefits

Interviewees confirmed that the type of agriculture practiced by Latinos can be framed as sustainable agriculture. They explained that many Latinos engage in this type of agriculture due to a lack of resources, including time, land, and capital. Consequently, they rely on the low-input agricultural methods familiar to them from their home countries. Others are motivated by a desire to preserve their culture, traditions, and connection to the land. Regardless of the motivation, these practices contribute to increasing food diversity and food security within their communities while also supporting alternative agricultural models.

The cultural significance of these practices cannot be overstated. By maintaining traditional agricultural methods, Latino farmers preserve a wealth of knowledge and biodiversity that might otherwise be lost. This cultural heritage supports community identity and provides a foundation for teaching future generations about sustainable farming.

There is a clear need to support and expand these efforts. Providing Latino farmers with access to additional resources, technical assistance, and education on sustainable practices can amplify the positive impacts they are already making. Such support would enable them to scale their operations sustainably, enhancing both their economic viability and their contributions to broader agricultural sustainability goals.

Social Benefits

On a social level, the research underscores the value of building stronger community ties and enhancing the overall quality of life for Latino farmers. Community-based approaches, like employing bilingual extensionists and tailoring outreach strategies, can foster trust and deepen engagement within the Latino farming community. Programs offering one-on-one technical assistance and culturally relevant training can empower Latino farmers, boosting their confidence and skills in managing their farms. Moreover, addressing broader socio-economic needs, such as healthcare access and immigration assistance, can reduce stress and improve well-being.

During the year 2022, the activities of the research project focused on establishing contact with institutions and individuals that could be gatekeepers to find and access Latinx farmers in the state of Pennsylvania. Based on data from the 2017 agricultural census, it was determined that there is a concentration of Latinx farmers in the southeast of the state (see figure 1).

Between May and August 2002, the PI focused on scouting Harrisburg, Lancaster, York, and Chester Counties. A list of restaurants and stores that provide services and products to the Latino community was prepared based on online information. The following steps were followed during visits to each of the businesses on the list. Flyers in English and Spanish were posted on the stores' and restaurants' notifications boards. The posters covered general information promoting the research and inviting the population to be part of the interview (see figure 2). The owners of the premises were also consulted to obtain information on Latino producers who supplied them or other Latino businesses that should be visited. The Spanish American Civic Association, Casa, Tec Centro, and La Comunidad Hispana were also seen.

Figure 2: Recruiting material in English and Spanish.

Other efforts to contact Latinx farmers in Pennsylvania included the presentation of the research project to PA Sustainable Agriculture (PASA) members and using their listserv to present and promote the study and find possible participants. Also, the research was promoted through the Penn State Latinx Agricultural Network and advertised through their listserv.

Despite various efforts to establish contact with Latinx farmers, it was not possible to establish interviews. In the case of two Latinx farmers in Chester County who initially agreed to be interviewed, they decided to decline the same day the interview was programmed.

Learned lessons

The difficulty of contacting farmers of Hispanic origin in the State of Pennsylvania can point to different reasons. First, language and literacy barriers and fear of working with the USDA or other governmental entities due to their immigration status can hinder their willingness to share their information. These barriers can make them a ‘hard-to-reach’ group, while only those with specific characteristics are more likely to participate. This leads to the second point; Latinx farmers in the census categorized as principal operators might also be farm managers, which might explain their concentration in localities like Chester county (known for mushroom farms) and where personnel with bilingual skills are desired.

Nonetheless, in the State, several institutions and programs, including PASA, PSU Latinx Agricultural Network, and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, have projects supporting new farmers and specifically supporting Latinx farmers in the region.

Research Activities 2023-2024

During the 2023-2024 period, the research concentrated on gathering data via in-depth interviews. These interviews involved various representatives from organizations that offer support services to Latinx Farmers in the Northeastern United States. The research yielded a comprehensive total of 40 interviews, segmented by location and organization type as follows: Massachusetts accounted for four interviews, Pennsylvania for 23, New York for 11, and Washington for two. Furthermore, there were two interviews with agriculture-focused NGOs having national-level representation (see Table 1). Participation in the data collection process also extended to various events, including the Spanish session of the Mid-Atlantic Fruit and Vegetable Conference in Hershey, PA. This provided an opportunity to establish contacts for expanding the pool of interviewees.

|

Table 1. Interviews distribution by state and organization type |

|||||

|

Organizations Type |

State |

Total |

|||

|

Massachusetts |

Pennsylvania |

New York |

Washington D.C |

||

|

Agri-focused NGO |

2 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

13 |

|

Land Grant Extension |

2 |

15 |

7 |

0 |

24 |

|

Government |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

|

4 |

23 |

11 |

2 |

40 |

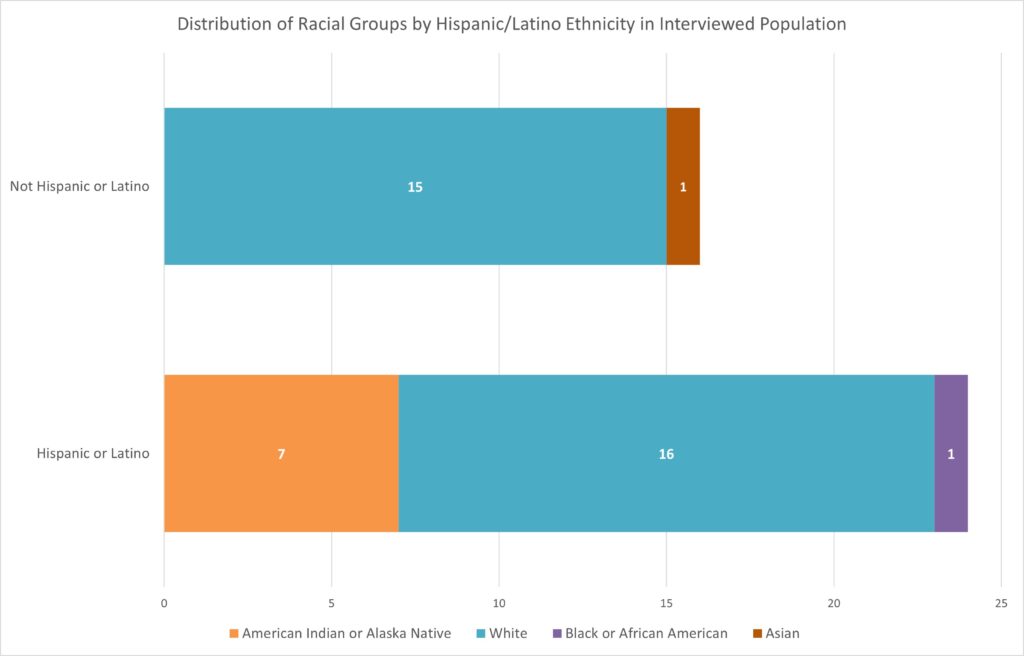

The following graph illustrates the racial composition of interviewees, emphasizing the distribution across different racial and ethnic groups. Interviewees in this study hold various roles, including field-based extension agents, university academics with extension responsibilities, and decision-makers at both NGO and government levels. The graph shows a predominance of White individuals in both ethnic categories, with 16 Whites among Hispanic or Latino individuals and 15 Whites among Not Hispanic or Latino individuals. There is a notable presence of American Indian or Alaska Native individuals within the Hispanic or Latino category, with 7 individuals, while none are present in the Not Hispanic or Latino category. The representation of Black or African American and Asian individuals is very low, with only 1 Black or African American individual in the Hispanic or Latino group and none in the Not Hispanic or Latino group. Similarly, there are no Asians in the Hispanic or Latino group and only 1 in the Not Hispanic or Latino group. Importantly, the data underscores the presence of individuals of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity in positions that support Latino farmers. Additionally, among the interviewees, 26 were bilingual in Spanish and English, and 18 reported that Spanish is their native language.

Findings

Insights from interviews with representatives of organizations serving Latino farmworkers highlight numerous barriers these workers face on their path to becoming farmers. Key challenges include occupational hazards, language barriers, lack of education, fear of arrest or deportation, and difficulties accessing federal aid and healthcare programs. Additionally, Latino immigrant farmers encounter significant hurdles with USDA programs due to a mismatch between their agrarian norms and the state's standardization requirements, leading to racial exclusion and unequal access to opportunities. The lack of access to essential services, particularly healthcare, poses another major obstacle. This issue is compounded by common rural barriers, language obstacles, unfamiliarity with the medical system, lack of health insurance, and financial difficulties aggravated by limited workers' rights. These multifaceted issues underscore the complex socio-economic and cultural challenges preventing Latinos from fully engaging in farming activities in the USA.

Supporting Latino Farmworkers in the Northeast: Challenges and Strategies for Effective Engagement

Government entities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and Land Grant extension services in the Northeast of the United States provide support to Latinos who are part of the farming industry. Recognizing Latinos as a vital part of the workforce in diverse industries such as dairy farming, fruit production, and horticulture, organizations have concentrated their efforts on providing education about technical aspects of agricultural production. The provision of services to the Latino farmworker community has driven organizations to recruit bilingual personnel to effectively deliver essential education and training. Specifically, organizations have recruited few individuals proficient in Spanish and possessing cultural competence.

In the interviews, field technicians reported that continuous interaction with the community has enabled them to identify additional needs, including assistance with immigration issues, access to healthcare, and support for individuals interested in initiating their own agricultural production.

At Land Grant Universities, technicians engage in a variety of ad hoc activities to support the Latino community in their transition to becoming farmers. These technicians emphasize that they cannot deliver training and education services in the same structured manner as those provided for long-established farmers. A technician based in Pennsylvania noted:

"...[working with Latino farmers], we must adapt to their schedules, as those who want to start their own production do so as a secondary activity during their available time. This demands more from the technicians, requiring us to accommodate their timings, which are typically outside of regular working hours or on weekends. Additionally, we must consider all the activities necessary to build trust with the community, such as attending events, celebrations, and similar occasions..."

On the other hand, the classification of Latinos mostly as farmworkers influences the design and delivery of educational and support services, which are predominantly aimed at addressing the needs of farm workers rather than farm owners. Such a perspective may inadvertently overlook the aspirations and potential of Latinos to own and operate farms, thus limiting the scope of support to immediate labor-related concerns rather than encompassing broader entrepreneurial and ownership opportunities.

Educational and Support Services

Educational initiatives are largely focused on imparting practical skills related to farm labor, such as crop management, pest control, and machinery operation. While these are undoubtedly valuable, there is a disparity in the provision of training that would empower Latinos to transition into farm ownership and management. Programs that do address farm management are less frequently offered and may not be as accessible to the Latino community, potentially due to language barriers, cultural nuances, or the lack of targeted outreach.

Grassroots Organizations' Role

The approach of grassroots organizations in Massachusetts and New York stands out as an exception to the general trend. By acknowledging Latinos not just as farmworkers but as current or aspiring farm owners, these organizations are pioneering a shift towards more inclusive and empowering models of support.

For instance, in New York, an NGO has significantly increased the number of Latino extensionists, specifically focusing on bilingual speakers who can effectively engage with the Latino community. This organization has identified several barriers that Latino farmworkers face in accessing their services. In response, they have adapted their outreach strategies to better reach this community. They identified hubs of Latino concentration in rural areas and regularly travel to these locations to promote their services. By interacting directly with farmworkers, they build trust and awareness of the NGO's offerings, effectively bridging the gap between the community and the support available to them.

In Massachusetts, a notable example is an Agri-focused NGO's partnership with UMASS, which provides comprehensive education on crop and pest management, pesticide use and safety, food safety, and risk management. Participants in this program benefit from one-on-one technical assistance and ten professionally led workshops. These sessions not only ensure participants can successfully operate small farms but also facilitate dependable networks, expanded financing opportunities, and a professional community of practice. Additionally, participants are eligible for mileage reimbursement. This initiative is tailored specifically for Latinos, focusing on equipping them with the skills, knowledge, and networks needed to successfully launch or support an agricultural business.

Their efforts to provide education on production for sale and self-consumption demonstrate a deep understanding of the diverse aspirations within the Latino farming community. For instance, "La Nueva Siembra" in New York offers workshops that focus on both commercial farming techniques and sustainable practices for self-sufficiency. A program director from this organization emphasized that support for Latinos transitioning to farming must go beyond mere translation of texts and technical assistance. To build trust with the community, it is crucial to view them holistically, recognizing and addressing the various barriers they face.

A holistic approach not only recognizes the entrepreneurial spirit among Latino farmers but also addresses a broader range of needs, from technical farming skills to business management and market access. Interviewees from both states consistently noted the importance of such holistic support systems.

Implications for Policy and Practice

The preliminary analysis suggests a need for a more nuanced understanding and approach to supporting Latino farmers. There is a gap between the services offered and the potential needs and aspirations of the Latino farming community. Bridging this gap requires a shift in perception among service providers, from seeing Latinos solely as laborers to recognizing them as current and future farm owners and operators. This shift could lead to more comprehensive support services that include business planning, financial management, and market access, in addition to the technical farming skills already provided.

Furthermore, the success of grassroots organizations in engaging with Latino farmers on these terms highlights the importance of community-based approaches that are closely aligned with the needs, languages, and cultures of the populations they serve. For instance, the initiatives in Massachusetts and "La Nueva Siembra" in New York illustrate how tailored programs, which address both technical and broader socio-economic needs, can effectively support Latino farmers. The New York NGO's strategy of employing bilingual extensionists and conducting outreach in Latino hubs demonstrates the value of culturally competent and accessible services. Similarly, the Massachusetts Agri-focused NGO's partnership with UMASS, which offers comprehensive training and networking opportunities, showcases the benefits of integrating educational and financial support.

Adopting such approaches more broadly could enhance the effectiveness of support services and contribute to the growth and sustainability of Latino-owned farming enterprises. By focusing on holistic support that includes building trust, addressing barriers beyond agriculture, and fostering a community-centric model, service providers can better meet the diverse needs of Latino farmers, ultimately promoting their success and integration into the broader agricultural landscape.

This study provided valuable insights into the challenges of accessing a hard-to-reach population, specifically Hispanic/Latinx farmers, and illuminated the broader implications of how this population is framed within agricultural systems. Initially, the research aimed to interview Latinx farmers directly to understand their experiences and challenges as farm owners. However, the difficulty in accessing this population necessitated a shift in focus to staff members of organizations that support Latinx farmers. This pivot highlighted key aspects of project implementation that both contributed to its success and posed challenges.

One of the primary challenges was the limited visibility and accessibility of Latinx farmers as a target group. Many are geographically dispersed and operate on smaller scales, which can make them less connected to mainstream agricultural networks. Additionally, the framing of Latinx individuals predominantly as farmworkers rather than farmowners in agricultural systems and policies compounded the difficulty of identifying and recruiting participants. This systemic issue not only influenced the research approach but also reflected the broader invisibility of Latinx farmers in policy and institutional contexts. This framing often results in Latinx farmers being overlooked as a distinct population with unique needs, further marginalizing their voices in discussions about sustainable agriculture.

The decision to pivot to interviewing staff members of organizations supporting Latinx farmers was a necessary and ultimately beneficial adjustment. This shift allowed the research to explore institutional perspectives, uncovering how organizations frame their work with Latinx farmers and the barriers they face in providing effective support. While this approach yielded valuable data, it underscored the need for future research to prioritize strategies that can directly engage Latinx farmers. One potential strategy is building partnerships with trusted community leaders or networks that have established relationships with farmers, as these actors can act as intermediaries to facilitate access and build trust.

Another lesson learned from the project is the importance of addressing structural barriers that limit Latinx farmers' visibility as farmowners. Policies and institutional practices that reinforce their framing as farmworkers rather than farmowners perpetuate their exclusion from critical resources and opportunities. Future research and educational initiatives should advocate for reframing Latinx farmers within agricultural systems, emphasizing their roles as innovators and leaders in sustainable farming. This shift in narrative can create pathways for better access, inclusion, and representation in both research and policy-making.

For future research, prioritizing areas with a high concentration of Hispanic/Latinx populations engaged in agriculture, such as Kennett Square, could significantly enhance the feasibility and depth of the study. Such regions offer a more accessible population base, increasing the likelihood of meaningful engagement. Researchers should consider dedicating time to volunteer efforts within these communities to build trust and establish relationships. Activities such as supporting food pantries, participating in health service initiatives, or engaging with other community-focused organizations can provide valuable opportunities to connect with local residents and gain a deeper understanding of the services and resources they rely on.

This approach not only fosters trust but also allows researchers to familiarize themselves with the lived realities of the community, which can inform more culturally sensitive and contextually relevant research designs. By becoming part of the community's ecosystem, researchers can better position themselves as allies, encouraging participation and open dialogue. Combining this community-centered approach with bilingual outreach efforts and leveraging existing community networks can further enhance engagement.

Additionally, focusing on these high-density agricultural areas allows for a more concentrated study, reducing logistical challenges while providing richer, localized insights into the experiences and needs of Latinx farmers. These strategies can form the foundation for future research efforts aimed at amplifying the voices of Latinx farmers and addressing the systemic barriers they face in sustainable agriculture.